Abstract

Service robots are emerging quickly in the marketplace (e.g., in hotels, restaurants, and healthcare), especially as COVID-19-related health concerns and social distancing guidelines have affected people’s desire and ability to interact with other humans. However, while robots can increase efficiency and enable service offerings with reduced human contact, prior research shows a systematic consumer aversion toward service robots relative to human service providers. This potential dilemma raises the managerial question of how firms can overcome consumer aversion and better employ service robots. Drawing on prior research that supports the use of language for building interpersonal relationships, this research examines whether the type of language (social-oriented vs. task-oriented language) a service robot uses can improve consumer responses to and evaluations of the focal service robot, particularly in light of consumers’ COVID-19-related stress. The results show that consumers respond more favorably to a service robot that uses a social-oriented (vs. task-oriented) language style, particularly when these consumers experience relatively higher levels of COVID-19-related stress. These findings contribute to initial empirical evidence in marketing for the efficacy of leveraging robots’ language style to improve customer evaluations of service robots, especially under stressful circumstances. Overall, the results from two experimental studies not only point to actionable managerial implications but also to a new avenue of research on service robots that examines customer-robot interactions through the lens of language and in contexts that can be stressful for consumers (e.g., healthcare or some financial service settings).

Similar content being viewed by others

Organizations are increasingly using robots to provide services to their customers (Wirtz et al., 2018), from hotels (e.g., robot concierges; Trejos, 2016) to hospitals (e.g., counselors, ICU; Alexander, 2020) to schools (e.g., nutrition educators; Abrahams, 2017) (see Table 1). This shift toward service robots is being accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic and is likely to last (Henkel et al., 2020) as organizations replace some of their human customer-contact employees with frontline robots (Lew, 2020). However, given the crucial role employees play in many services (which are social encounters that often nurture customer-firm relationships), it is important to better understand consumer responses to frontline robots, whether these responses might be affected by the ongoing pandemic and ways companies can better employ service robots.

Because consumers are not always comfortable with robots (Longoni et al., 2019; Mende et al., 2019), more research is needed on how to influence consumer favorability toward service robots. Therefore, we examine the interactive effects between consumer-perceived stress (here, related to COVID-19) and a robot’s language styleFootnote 1 on consumers’ responses. Consumers tend to prefer human employees over robots because of the social aspects of interpersonal service encounters (Mende et al., 2019). Notably, with COVID-19 concerns and social distancing guidelines, people have been restricted in their ability to interact with other humans. This provides an opportunity for marketers to leverage social robots to fill this gap if only robots were (more) acceptable to consumers. We propose that a robot’s language style can help to improve customer-robot interactions both by increasing the perceived “humanness” of the robot and by providing social interactions, which may be particularly valued by consumers in times of stress. A social-oriented language style, characterized by informal and casual conversations that enable an exchange of social-emotional and affective information (Chattaraman et al., 2019), might be particularly well suited to fulfilling these goals. Thus, we study how language might “humanize” robots and how consumer service evaluations change as a function of language and COVID-19 stress.

Linking research on robots and anthropomorphism with literature on language styles, we provide novel insights into how marketers can more effectively use robots. Consistent with prior literature, study 1 shows that among different provider types (human, humanoid robot, and mechanical robot), consumers are least favorable toward mechanical robots. Thus, study 2 deliberately focuses our language intervention on mechanical robots to identify how companies can tackle this major challenge. Consistent with our theorizing, we find that a social-oriented language style improves consumer perceptions of mechanical robots and that the benefits of a social-oriented (vs. task-oriented) language style increase as consumer stress increases.

Our findings make several contributions to marketing. First, we introduce language style as an effective mechanism for improving consumer evaluations of robots, a novel insight that is relevant for marketing scholars and managers. While prior literature on robots has explored different facets of anthropomorphism (Blut et al., 2021), it has focused on the physical attributes of robots. The language style is a potentially less costly, more flexible, and easier to implement aspect of robots.

Second, our research reveals how (COVID-19) stress changes consumer responses to service providers. As stress increases, consumers show a greater preference for robots using social- (vs. task-)oriented language, suggesting a greater desire to connect with a service provider. Service robots are used in numerous contexts in which consumers may experience acute stress (e.g., healthcare) and during times of chronic stress (e.g., COVID-19 pandemic) (Henkel et al., 2020). Accordingly, our results suggest that service providers adopt language styles that are social- (vs. task-)oriented as a platform for better connecting with consumers.

Finally, our work contributes to research on the effects of language in services. While the relevance of language in services has been recognized (Holmqvist and Grönroos, 2012), most research in this domain examines questions related to multilingual speakers with limited research examining stylistic aspects of language (Mariani et al., 2019), and even less examining language in customer-robot encounters (Choi et al., 2019 for an exception). We demonstrate the efficacy of social-oriented language for improving customer-robot interactions and suggest that language style can reduce discomfort for consumers experiencing stress.

1 Consumer responses to service robots and the role of human-likeness

The focus on service robots is fueled by companies striving to stay competitive by engaging customers through cutting-edge technology. Against this background, frequently, a robot’s human-like appearance is believed to be an effective way to better engage consumers. The corresponding theoretical phenomenon is anthropomorphism, “the attribution of human characteristics or traits to nonhuman agents” (Epley et al., 2007, p. 865).

Robots are often designed with human-like features to inspire trust and encourage humans to bond with them (Broadbent et al., 2011; Rau et al., 2009). Indeed, people can more easily follow social scripts and apply norms of human–human interaction when they encounter more human-like robots (Nass and Moon, 2000). Consistent with these insights, Bloomberg (2017) observed that humanoid robots in the marketplace are “easy to relate to thanks to their human-like mannerisms and emotions.” Accordingly, managers may deem it beneficial to use more human-like (vs. more mechanical) service robots.

However, the effects of human-like robots on humans are complex. For example, on the one hand, the concept of the “uncanny valley” (Mori, 1970) suggests that humanoid robots that imitate but fail to attain humanness fully might trigger discomfort (e.g., eeriness) (Broadbent et al., 2011). On the other hand, empirical evidence of the uncanny valley remains inconsistent (Kätsyri et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015). Against this background, the meta-analysis by Blut et al., (2021, p. 17) provides valuable insights: it shows that anthropomorphism has a strong positive effect on consumer intentions to use service robots, and humanlike perceptions “facilitate human–robot interactions, helping customers to apply the familiar social rules and expectations of human–human interactions.”

Synthesizing the above insights, we theorize that the service provider’s perceived humanness affects consumers’ service evaluation. Specifically, consumers should respond to humans more favorably than to humanoid robots, but more favorably to humanoid robots than to mechanical robots.Footnote 2

2 Social- vs. task-oriented language style in service encounters

While anthropomorphism is typically operationalized as physical features, a robot’s appearance is not the only facet that can cue humanness (Murphy et al., 2017). Language is a fundamentally human trait that both transfers information and impacts social relations (Spencer-Oatey, 2000). Indeed, human interaction rituals - such as greetings, small talk, and leave taking (farewell salutations) - can increase trust in technology (Cassell and Bickmore, 2000), and when asked about expectations of robot companions, participants judge human-like communication as more important than human-like behavior or appearance (Blow et al., 2006).

Language is also an important facet of customer-employee interactions that can influence service quality perceptions (Holmqvist and Grönroos, 2012). While prior literature examining language in services largely focuses on multilingual consumers (Mariani et al., 2019), a smaller but growing stream of research investigates language styles (e.g., Li et al., 2019; Packard and Berger, 2021). Nonetheless, the effects of the tone of language on services remain understudied, especially related to customer-robot encounters.

Extending the marketing literature, we examine how language style influences consumers’ evaluations. We propose that social-oriented vs. task-oriented language styles can affect customers’ service assessments. A social-oriented language style involves informal, relational dialogue with social interactions such as greetings, small talk, emotional support, and positive emotions to achieve socio-emotional goals (Bickmore and Cassell, 2001; Yoo et al., 2015). In contrast, a task-oriented language style is more formal and focuses on achieving functional goals (Chattaraman et al., 2019). We theorize that firms can leverage these language styles in customer-robot encounters, as discussed next.

3 Service robots and language style

Answering calls for empirical investigations on how technology shapes service encounters (Rafaeli et al., 2017), we study the impact of language style of three types of service agents: human providers, humanoid robots, and mechanical robots. Prior research shows that language influences perceptions of the speaker, and we propose that this includes robots. Social response theory argues that humans tend to interact with computers and media as they do with other humans (Nass and Moon, 2000). Conversational norms of human employees can therefore apply to robots (Epley et al., 2007), and consumers are likely to expect similar conversational styles for humans and human-like robots (Choi et al., 2019). Accordingly, we theorize that firms can use language styles to improve consumer evaluations of robots. Kattara and El-Said (2013) indicate that hotel guests’ preferences for human-staffed (vs. robot-staffed) hotels occur due to humans’ perceived “hospitableness” and empathy. The language might increase such hospitableness and empathy of a service provider and thus could be used to improve preference for robots.

4 Effects of consumer stress related to COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased stress levels for many people (e.g., anxiety related to unemployment, economic uncertainty, or family demands; Masiero et al., 2020). Consumer stress can alter cognition and decision-making (Lupien and Lepage, 2001), and it can affect consumers’ service preferences and perceptions (Berry and Bendapudi, 2007; Berry et al., 2015). Paradoxically, while COVID-19 increases consumers’ desire for social distance and reduced contact with humans, it also makes consumers yearn for social contact and support. The reason for such social yearning is that positive social interactions before or during stress exposure can help reduce stress reactivity (von Dawans et al., 2012) because social support bolsters calmness and lowers cortisol concentration and anxiety during stress (Heinrichs et al., 2003). Given such positive effects of social support, a language style that signals social support may be particularly beneficial for those experiencing COVID-19 stress. Specifically, related to the increased social distancing during the pandemic, we theorize that a “warmer tone” such as expressed through the use of social-oriented (vs. task-oriented) language may be more beneficial.

Synthesizing the above insights, we theorize that when consumers are experiencing higher (vs. lower) COVID-19 stress, they will perceive a robot more favorably when it uses social-oriented language; but they will be relatively unaffected when the robot uses task-oriented language. Furthermore, we theorize that the potentially positive response to social- (vs. task-) oriented language is particularly evident in response to service robots (vs. human employees) because the “humanness” of employees already serves to provide interpersonal cues.

5 Study 1

Study 1 examines whether, as we theorized above, consumers respond to humans more favorably than to humanoid robots but more favorably to humanoids than to mechanical robots. To explore this question, we employ a 3-cell (service providers: a mechanical robot, humanoid robot, human) between-subjects design. We used an online nutrition coaching program context due to the importance of nutrition for health, its interest to a wide range of consumers, and its external validity because robots are being used in such services (Topol, 2019, also Table 1).

5.1 Method

One hundred eighty Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) workers participated in the study. Thirty-seven participants failed the attention checks and were removed (final N = 143; Mage = 35–45 years; 53.1% female). All participants read the same scenario about an online nutrition coaching program that described the philosophy of the coaching program in order to familiarize participants with such programs. Next, participants viewed an advertisement for the program that contained an image of the nutrition coach (a mechanical robot, a humanoid robot, or a human; see Web Appendix A for stimuli). Then, participants completed the dependent measure: service evaluation was assessed based on a 5-item service evaluation index (α = 0.956; Zeithaml et al., 1996)Footnote 3 (see Table 2 for items). Participants also completed manipulation checks (“The nutrition coach is like a person”; “The nutrition coach is robotic” [R], r = 0.918) and demographics.

5.2 Results and discussion

Manipulation checks (perceived humanness)

A one-way ANOVA showed a significant provider type main effect (F(2, 140) = 109.90; p < 0.001). The mechanical robot (Mmech = 1.68) was perceived as less human (more robotic) than the humanoid robot (Mhumanoid = 4.62; p < 0.001) and human (Mhuman = 5.87; p < 0.001); the human was perceived as more human than the humanoid robot (p < 0.001). Thus, the provider type manipulation performed as intended.

Service evaluation

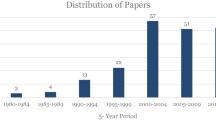

ANOVA with service evaluation as the outcome and provider type as the independent variable revealed a provider type main effect (F(2, 140) = 12.11; p < 0.001). The mechanical robot elicited less favorable service evaluations than both the humanoid robot provider (Mmech = 2.91; Mhumanoid = 4.02; p < 0.001) and the human provider (Mmech = 2.91; Mhuman = 4.47; p < 0.001). Evaluations of the humanoid robot and human were not significantly different (Mhumanoid = 4.02; Mhuman = 4.47; p = 0.17) (see Fig. 1).

These results are partially consistent with our theorizing, as a provider’s humanness influences service evaluations positively. However, although the human and the humanoid robot differed in perceived humanness (per the manipulation check), participants did not significantly differ in their service evaluations across these two conditions. That is, using mechanical robots poses a relatively greater challenge for companies, even though such robots are more common in practice (Rafaeli et al., 2017). Therefore, study 2 will test a novel intervention firms can use to improve consumer responses to mechanical robots, as these (less-anthropomorphized) robots appear to represent a greater “hurdle” for consumers.

6 Follow-up study

In study 1, although the human and humanoid robots had many visual similarities, we note that the human service provider was smiling, and the humanoid robot appeared to have a relatively more neutral facial expression. We, therefore, conducted a follow-up study to examine whether the two might be perceived differently in terms of warmth or competence. Sixty MTurk participants (29 females; age 18–34 = 50%) were randomly assigned to view one of the two service provider images from Study 1 (humanoid robot vs. human) and then answer questions about the provider’s warmth (warm, unselfish, caring, kind, friendly, considerate, polite, helpful, likable, and trustworthy) and competence (competent, intelligent, well trained, professional, skilled, appropriate, and honest; Fiske et al., 2002; Scott et al., 2013; Wojciszke, 2005). The presentation of the items was randomized and they were measured on a 7-point strongly dis-/agree scale.

The results confirm that the human is perceived as having greater humanness (Mhumanoid = 4.90; Mhuman = 5.69; F(1, 58) = 5.33; p = 0.03). However, the humanoid robot and human are not perceived differently in terms of warmth (Mhumanoid = 5.29; Mhuman = 5.69; F(1, 58) = 1.99; p = 0.16; α = 0.94) or competence (Mhumanoid = 5.72; Mhuman = 5.83; F(1, 58) = 0.15; p = 0.71; α = 0.94). Furthermore, the results in study 1 might be considered conservative inasmuch as the difference in evaluation is NS between the humanoid robot and human, despite the fact that the human has a smiling facial expression.

7 Study 2

Study 2 investigates whether language style (i.e., social vs. task oriented) can serve as a novel intervention and improve consumers’ service evaluations, especially when consumers interact with a mechanical robot. As needs for social warmth changed during the COVID-19 pandemic (Masiero et al., 2020), we also examine whether the impact of language styles on service evaluation varies across provider types (human and mechanical robot) in light of (higher vs. lower) consumer stress during the pandemic.

7.1 Method

This study employed a 2 (language style: social vs. task oriented) × 2 (provider: mechanical robot vs. human) between-subjects design, with COVID-19 stress as a measured third factor. Two hundred fifty MTurk workers participated in this study. Thirteen participants failed the attention checks and were removed (final N = 237; Mage = 30–39 years; 47.9% female). Participants viewed either the mechanical robot or human service provider stimuli from Study 1, followed by a short conversation between the nutrition coach and Alex, a first-time client. The client’s responses were the same across conditions, but the nutrition coach’s (i.e., provider’s) language was manipulated as either a social-oriented or task-oriented style. A pretest confirmed that the social-oriented language style was perceived as more social than the task-oriented language style (Msocial = 5.61; Mtask = 4.37; t(76) = 4.90; p < 0.001) (see Web Appendices B and C for stimuli and pretest, respectively). After viewing the scenario/advertisement, participants completed service evaluation measures, manipulation checks for provider type, a COVID-19 stress index (α = 0.728, adapted from Menon et al., 2002) (Table 2), and demographics and were debriefed.

7.2 Results

Manipulation checks

A service provider × language style ANOVA with perceived humanness as the dependent variable revealed only a provider type main effect. The human was perceived as more human than the robot (Mrobot = 3.05; Mhuman = 5.12; F(1, 233) = 36.89; p < 0.001), as intended. No other effects (p’s > 0.1) were significant.

Service evaluation

To explore our theorizing, we used a moderation approach to examine a 2 (provider: robot, human) × 2 (language style: social- vs. task-oriented) × (COVID-19 stress: measured and centered) model (process model 3, Hayes, 2017). The analysis revealed a three-way interaction (b = − 0.61; p = 0.06). The model also showed a provider main effect (b = − 0.96; p < 0.001), such that the service was evaluated more favorably when the provider was human (coded as 0) vs. robotic (coded as 1), consistent with study 1. No other effects were significant (p’s > 0.1). To further explore the three-way interaction, we analyzed effects at each level of provider type (human vs. robot), see Fig. 2.

For the robot provider, there was a language style × COVID-19 stress interaction (b = − 0.43; p = 0.048). The model also revealed a COVID-19 stress main effect (b = 0.46; p < 0.001), but no language style main effect (p = 0.41). That is, as COVID-19 stress increases, consumers evaluate the service more favorably with social-oriented language (p < 0.001); there is no such effect for task-oriented language (p = 0.85). Furthermore, when consumers are under high COVID-19 stress, they are significantly more favorable toward social-oriented (vs. task-oriented) language from a robot (p = 0.045), but not under low stress (p = 0.45) (Fig. 2A).

For the human provider, neither the main effects of COVID-19 stress (b = 0.26; p = 0.18) nor language style (b = − 0.02; p = 0.93) nor their two-way interaction were significant (b = 0.19; p = 0.45) (Fig. 2B).Footnote 4

8 General discussion

This research contributes to the marketing literature both with respect to the use of robots and language in services. Service robots are increasingly being used in a variety of contexts (e.g., hotels, airlines/airports, and hospitals), but consumers display mixed responses to them (Longoni et al., 2019). Research suggests that consumer responses to robots are complex but that humanlike perceptions facilitate human–robot interactions (Blut et al., 2021). Our research shows that consumers prefer humans and humanness (study 1) but that a social-oriented language style can increase acceptance of service robots, particularly for consumers experiencing stress (study 2).

Our work is among the first studies in marketing using language to increase consumers’ evaluations of service robots, which is important for several reasons. First, language style is a potentially less costly, more flexible, and easier to implement aspect of robot design than physical manipulations of anthropomorphism, making the findings more actionable for companies. Second, prior research calls on scholars to study robots in dynamic interactions (vs. static perspectives; Paetzel-Prüsmann et al., 2021). While we used a scenario to illustrate a robot-customer interaction, by showing how the robot speaks and interacts with a customer over the course of the encounter, we provide a fuller picture of the robot, which may have helped increase the sense of connection with the robot leading to higher service evaluations. Third, by studying social-oriented (vs. task-oriented) language, we examine the impact of tone, which has been an understudied area of language in marketing (Holmqvist and Grönroos, 2012).

Our research expands on research by Choi et al. (2019), which explored whether the effectiveness of language styles varies by service agent (human, robot, service kiosk). In contrast to Choi et al. (2019), who focus on the impact of figurative vs. literal language on perceived credibility (and consequent service evaluation) as a function of conversational norms, we study social-oriented vs. task-oriented language and consider the impact on service evaluation as a function of perceived humanness and warmth/social connection. While we find that social-oriented language can improve perceptions of mechanical robots, Choi et al. (2019) find that language effects do not extend to service kiosks due to their lack of anthropomorphism. Furthermore, our research also introduces the role of stress and how that impacts consumers’ responses to language style and service provider type.

With its focus on robot language, our research raises interesting questions for future research. The use of social-oriented (vs. task-oriented) language is just one aspect of language that has been associated with rapport-building strategies. For example, Packard and Berger (2021) find that concrete (vs. abstract) language can signal that human employees are listening to consumer needs, thereby increasing customer satisfaction. Campbell et al. (2006) propose that specific communication behaviors, such as using questions and repeating the customer’s words, can improve rapport. Similarly, Gremler and Gwinner (2008) highlight several behaviors, such as voice tone and using congenial greetings, that increase rapport between customers and retail employees. Future research could explore how these and other aspects of language influence service perceptions and whether some language styles are differentially effective for different providers, such as service robots. Such studies should also be conducted longitudinally, particularly to see how repeated interactions with robots change perceptions over time.

Our research also contributes to the literature by exploring the impact of stress on consumer responses to service providers. We find that social-oriented language can increase connections with robots, especially as consumer stress increases. Such findings are important for high-stress contexts, such as healthcare (Berry and Bendapudi, 2007), as well as for times of chronic stress. Indeed, in providing recommendations for how to enhance customer satisfaction for emotion-laden services (i.e., those that trigger strong feelings before service even begins), Berry et al., (2015, p. 7) write that “choice of words [and] tone of voice… can have a big impact on anxious customers who are looking for evidence of competence and compassion.” Consistent with this idea, our research suggests that choice of language and service provider are both aspects that managers should consider strategically to determine how to better meet consumer needs.

Future research and limitations

A limitation of our studies is the use of scenario-based studies, instead of encounters with real-life robots. Although our approach is consistent with research in leading marketing journals (e.g., Longoni et al., 2019; Mende et al., 2019), future research could incorporate real-life human–robot encounters.

Future research should also explore other ways robots can reduce stress, for example, by initiating mindfulness techniques or initiating touch. In addition, while we studied the social-oriented language to help improve evaluations of robots for those consumers who were experiencing stress, future research should examine the effectiveness of language styles in a broader range of contexts (e.g., hedonic vs. utilitarian services). Research should also consider whether all sources and types of stress are the same, as research finds that negative emotions (e.g., anger-sadness and anger-fear) often differ in their effects (Bodenhausen et al., 1994; Lerner and Keltner, 2001). For example, those experiencing uncertainty about finances may have different preferences towards robots and language styles than those experiencing stress about a personal loss, health, or loneliness.

Our research also contributes to the literature on the effects of language in service contexts more broadly. While we focused on a stylistic aspect of language due to its potential to create an affect-related customer-provider connection, language style is just one understudied dimension of language in services. Spencer-Oatey (2000) highlights several domains of language relevant to rapport-building, such as illocution, discourse content and structure, participation (e.g., turn-taking), and nonverbal behavior. Future research could explore these domains for service encounters in general and with respect to responses to service robots specifically.

Data availability

Materials and data that support the findings of these studies are available from the authors upon request.

Code availability

N/A.

Notes

Language style concerns stylistic aspects of an interchange, such as choice of tone, genre-appropriate lexis and syntax, and genre-appropriate terms of address or use of honorifics (Spencer-Oatey 2000).

Related to a growing discussion about the relevance of null hypothesis significance testing (e.g., Amrhein, Greenland, and McShane 2019), we do not introduce formal hypotheses; instead, we propose our theorizing and, consistent with the recent literature, assess p-values “continuously rather than in a dichotomous or threshold-ed manner” (McShane et al., 2019, p. 236); that is, we consider p-values as measuring the compatibility between our theorizing and data (Greenland 2019).

As expected, an exploratory factor analysis with the five measures (intention to sign up, service quality, likelihood of recommending the program, interest in the program, interest in learning more about the program) yielded a single factor (which accounted for 85.73% of the variance).

We note one unexpected significant contrast for the human service provider (Fig. 2B). We speculate that interacting with a human provider allows consumers to be more comfortable with the task-oriented language (i.e., the human-to-human interaction may compensate for the more task-oriented language). Furthermore, the contrast is driven by consumers who are relatively more stressed, which may help explain why they would be more accepting of the task-oriented language as long as the service provider is another human; however, when they interact with a mechanical robot, consumers prefer the machine to “compensate” through a social-oriented language.

References

Abrahams, M (2017). Robots and nutrition education-are we on the right path? https://marietteabrahams.com/2017/02/robots-nutrition-right-path/. Accessed 19 Jan 2022

Alexander, D (2020). 15 medical robots that are changing the world. https://interestingengineering.com/15-medical-robots-that-are-changing-the-world. Accessed 19 Jan 2022

Amrhein, V, Greenland, S, McShane, B (2019). Scientists rise up against statistical significance. Nature, 305–307.

Batory, C (2019). South Korea’s Dal.komm greatly extends the reach of robot baristas. https://dailycoffeenews.com/2019/06/19/south-koreas-dal-komm-greatly-extends-the-reach-of-robot-baristas/. Accessed 19 Jan 2022

Berry, L. L., & Bendapudi, N. (2007). Health care: A fertile field for service research. Journal of Service Research, 10(2), 111–122.

Berry, L. L., Davis, S. W., & Wilmet, J. (2015). When the customer is stressed. Harvard Business Review, 93(10), 86–94.

Bickmore, T, Cassell, J (2001). Relational agents: A model and implementation of building user trust. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on human factors in computing systems, March, 396–403.

Bloomberg (2017). Creating consumer buzz with human-like robots. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/videos/2017-03-30/creating-consumer-buzz-with-human-like-robots-video. Accessed 19 Jan 2022

Blow, M, Dautenhahn, K, Appleby, A, Nehaniv, CL, Lee, DC (2006). Perception of robot smiles and dimensions for human-robot interaction design. ROMAN 2006-The 15th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, September, 469–474. https://doi.org/10.1109/ROMAN.2006.314372.

Blut, M., Wang, C., Wünderlich, N. V., & Brock, C. (2021). Understanding anthropomorphism in service provision: A meta-analysis of physical robots, chatbots, and other AI. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 49(4), 1–27.

Bodenhausen, G. V., Sheppard, L. A., & Kramer, G. P. (1994). Negative affect and social judgment: The differential impact of anger and sadness. European Journal of Social Psychology, 24(1), 45–62.

Broadbent, E, Jayawardena, C, Kerse, N, Stafford, RQ, MacDonald, BA (2011). Human-robot interaction research to improve quality of life in elder care—An approach and issues. Proceedings of the 12th AAAI Conference on Human-Robot Interaction in Elder Care, January, 13–19.

Cairns, R (2021). Meet ‘EMMA’: The AI robot masseuse practicing ancient wellness therapies. https://www.cnn.com/2021/09/01/health/ai-robot-masseuse-tcm-wellness-hnk-spc-intl/index.html. Accessed 19 Jan 2022

Campbell, K. S., Davis, L., & Skinner, L. (2006). Rapport management during the exploration phase of the salesperson–customer relationship. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 26(4), 359–370.

Cassell, J., & Bickmore, T. W. (2000). External manifestations of trustworthiness in the interface. Communications of the ACM, 43(12), 50–56.

Chattaraman, V., Kwon, W. S., Gilbert, J. E., & Ross, K. (2019). Should AI-based, conversational digital assistants employ social-or task-oriented interaction style? A task-competency and reciprocity perspective for older adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 90, 315–330.

Choi, S., Liu, S. Q., & Mattila, A. S. (2019). How may I help you? Says a robot: Examining language styles in the service encounter. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 82, 32–38.

Crowe, S (2021). Digital dream labs gearing up for Cozmo, Vector relaunch. The Robot Report. https://www.therobotreport.com/digital-dream-labs-relauch-cozmo-vector-robots/. Accessed 19 Jan 2022

Epley, N., Waytz, A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2007). On seeing human: A three-factor theory of anthropomorphism. Psychological Review, 114(4), 864.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 878.

Fujitsu Corporation (2005), Fujitsu begins limited sales of service robot “enon” for task support in offices and commercial establishments, press release, https://www.fujitsu.com/global/about/resources/news/press-releases/2005/0913-01.html, accessed, February 2022.

Greenland, S. (2019). Valid p-values behave exactly as they should: Some misleading criticisms of p-values and their resolution with s-values. The American Statistician, 73, 106–114.

Gremler, D. D., & Gwinner, K. P. (2008). Rapport-building behaviors used by retail employees. Journal of Retailing, 84(3), 308–324.

Hayes, AF (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications.

Heinrichs, M., Baumgartner, T., Kirschbaum, C., & Ehlert, U. (2003). Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to psychosocial stress. Biological Psychiatry, 54(12), 1389–1398.

Henkel, Alexander P., Martina Čaić, Marah Blaurock, Mehmet Okan (2020). Robotic transformative service research: Deploying social robots for consumer well-being during COVID-19 and beyond. Journal of Service Management.

Heriot Watt University (2020). Socially pertinent robots. https://www.hw.ac.uk/uk/research/global/national-robotarium/socially-pertinent-robots.htm. Accessed 19 Jan 2022

Holmqvist, J., & Grönroos, C. (2012). How does language matter for services? Challenges and propositions for service research. Journal of Service Research, 15(4), 430–442.

Jingyi, H (2021). Hotel delivery robots bring winning edge to Chinese startup. https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/36Kr-KrASIA/Hotel-delivery-robots-bring-winning-edge-to-Chinese-startup. Accessed 19 Jan 2022

Kan, M (2021). Alphabet is using multi-tasking robots to tidy up Google offices. https://www.pcmag.com/news/alphabet-is-using-multi-tasking-robots-to-tidy-up-google-offices. Accessed 19 Jan 2022

Kätsyri, J., Förger, K., Mäkäräinen, M., & Takala, T. (2015). A review of empirical evidence on different uncanny valley hypotheses: Support for perceptual mismatch as one road to the valley of eeriness. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 390.

Kattara, H. S., & El-Said, O. A. (2013). Customers’ preferences for new technology-based self-services versus human interaction services in hotels. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 13(2), 67–82.

Lerner, J. S., & Keltner, D. (2001). Fear, anger, and risk. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(1), 146.

Lew, E (2020). Pandemic and the smarter world: a future of robots? https://leading.gsb.columbia.edu/features/pandemic-and-the-smarter-world-a-future-of-robots/. Accessed 19 Jan 2022

Li, X., Chan, K. W., & Kim, S. (2019). Service with emoticons: How customers interpret employee use of emoticons in online service encounters. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(5), 973–987.

Longoni, C., Bonezzi, A., & Morewedge, C. K. (2019). Resistance to medical artificial intelligence. Journal of Consumer Research, 46(4), 629–650.

Lupien, S. J., & Lepage, M. (2001). Stress, memory, and the hippocampus: Can’t live with it, can’t live without it. Behavioural Brain Research, 127(1–2), 137–158.

Mariani, M. M., Borghi, M., & Kazakov, S. (2019). The role of language in the online evaluation of hospitality service encounters: An empirical study. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 78, 50–58.

Masiero, M., Mazzocco, K., Harnois, C., Cropley, M., & Pravettoni, G. (2020). From individual to social trauma: Sources of everyday trauma in Italy, the US and UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 21(5), 513–519.

McShane, B. B., Gal, D., Gelman, A., Robert, C., & Tackett, J. L. (2019). Abandon statistical significance. The American Statistician, 73, 235–245.

Mende, M., Scott, M. L., van Doorn, J., Grewal, D., & Shanks, I. (2019). Service robots rising: How humanoid robots influence service experiences and elicit compensatory consumer responses. Journal of Marketing Research, 56(4), 535–556.

Menon, G., Block, L. G., & Ramanathan, S. (2002). We’re at as much risk as we are led to believe: Effects of message cues on judgments of health risk. Journal of Consumer Research, 28(4), 533–549.

Mitchell, H (2018). Robotic therapy is on the rise. Here’s Why. https://otpotential.com/blog/active-assistive-robotic-therapy. Accessed 19 Jan 2022

Mori, M. (1970). Bukimi no tani [the uncanny valley]. Energy, 7, 33–35.

Murphy, J, Gretzel, U, Hofacker, C (2017). Service robots in hospitality and tourism: Investigating anthropomorphism. 15th APacCHRIE Conference, 31, https://heli.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/APacCHRIE2017_Service-Robots_paper-200.pdf. Accessed 19 Jan 2022

Nass, C., & Moon, Y. (2000). Machines and mindlessness: Social responses to computers. Journal of Social Issues, 56(1), 81–103.

Packard, G., & Berger, J. (2021). How concrete language shapes customer satisfaction. Journal of Consumer Research, 47(5), 787–806.

Paetzel-Prüsmann, M., Perugia, G., & Castellano, G. (2021). The influence of robot personality on the development of uncanny feelings. Computers in Human Behavior, 120, 106756.

Rafaeli, A., Altman, D., Gremler, D. D., et al. (2017). The future of frontline research: Invited commentaries. Journal of Service Research, 20(1), 91–99.

Rau, P. P., Li, Y., & Li, D. (2009). Effects of communication style and culture on ability to accept recommendations from robots. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(2), 587–595.

Scott, M. L., Mende, M., & Bolton, L. E. (2013). Judging the book by its cover? How consumers decode conspicuous consumption cues in buyer–seller relationships. Journal of Marketing Research, 50(3), 334–347.

Spencer-Oatey, H. (2000). Rapport management: A framework for analysis. In H. Spencer-Oatey (Ed.), Culturally speaking: Managing rapport through talk across cultures (pp. 11–46). Continuum.

Topol, E. J. (2019). High-performance medicine: The convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nature Medicine, 25(1), 44–56.

Trejos, N (2016). Introducing Connie, Hilton's new robot concierge. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/travel/roadwarriorvoices/2016/03/09/introducing-connie-hiltons-new-robot-concierge/81525924/. Accessed 19 Jan 2022

Vincent, J (2019). Boston dynamics’ robots are preparing to leave the lab — Is the world ready? https://www.theverge.com/2019/7/17/20697540/boston-dynamics-robots-commercial-real-world-business-spot-on-sale. Accessed 19 Jan 2022

von Dawans, B., Fischbacher, U., Kirschbaum, C., Fehr, E., & Heinrichs, M. (2012). The social dimension of stress reactivity: Acute stress increases prosocial behavior in humans. Psychological Science, 23(6), 651–660.

Wang, S., Lilienfeld, S. O., & Rochat, P. (2015). The uncanny valley: Existence and explanations. Review of General Psychology, 19(4), 393–407.

Wessling, B (2022c). Starship Technologies raises $56M for delivery robots. The Robot Report. https://www.therobotreport.com/starship-technologies-raises-56m-for-delivery-robots/. Accessed 19 Jan 2022

Wessling, B (2022b). Percepto drones receive BVLOS approval at 2 U.S. refineries. The Robot Report. https://www.therobotreport.com/percepto-drones-bvlos-approval-2-us-refineries/. Accessed 19 Jan 2022

Wessling, B (2022a). Distalmotion, the company behind Dexter, raises $90 million in funding. The Robot Reprt. https://www.therobotreport.com/distalmotion-the-company-behind-dexter-raises-90-million-in-funding/. Accessed 19 Jan 2022

Wirtz, J., Patterson, P. G., Kunz, W. H., Gruber, T., Lu, V. N., Paluch, S., & Martins, A. (2018). Brave new world: Service robots in the frontline. Journal of Service Management, 29(5), 907–931.

Wojciszke, B. (2005). Morality and competence in person-and self-perception. European Review of Social Psychology, 16(1), 155–188.

Yoo, W., Kim, S. Y., Hong, Y., Chih, M. Y., Shah, D. V., & Gustafson, D. H. (2015). Patient–clinician mobile communication: Analyzing text messaging between adolescents with asthma and nurse case managers. Telemedicine and E-health, 21(1), 62–69.

Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The behavioral consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 60(2), 31–46.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kumar, S., Miller, E.G., Mende, M. et al. Language matters: humanizing service robots through the use of language during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mark Lett 33, 607–623 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-022-09630-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-022-09630-x