Abstract

Suicide among adolescents is a significant health concern. Gaining more knowledge about markers that contribute to or protect against suicide is crucial. Perfectionism is found to be a personality trait that is strongly predictive for suicidality; it can be divided into personal standards perfectionism (PS) and concerns about mistakes and doubts perfectionism (CMD). This study investigated the association between PS, CMD, and suicidality in a sample of 273 Dutch secondary school students aged between 12 and 15 years old (M = 13.54, SD = 0.58, 55.8% males). We also examined whether adaptive, or maladaptive cognitive coping strategies influenced these associations. We hypothesized that students high in PS or CMD would experience an increased suicidality. Moreover, we expected that adaptive coping strategies would act as buffer between the association of perfectionism and suicidality, and that maladaptive coping strategies would strengthen this association. For analyses, we used a regression model with latent variables. The results showed that higher scores in perfectionism (PS and CMD) were related to an increase in suicidality. High levels of maladaptive coping in combination with high levels of perfectionism were associated with an increase in suicidality. Although adaptive coping was related to a decrease in suicidality, adaptive coping in interaction with PS and with CMD was not a predictor of suicidality. The results are relevant for prevention, and intervention programs. This paper makes recommendations for clinical practice and further research in order to prevent suicidality in adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Suicide among adolescents is a significant health concern as it is the second leading cause of death in 15–29 year-olds worldwide, and the leading cause of death in the Netherlands in this age group (CBS 2018; WHO 2018). Research shows that a history of suicide attempts and suicidal ideations is the best predictor of a suicide (Joiner 2005). Suicidal ideation includes thoughts and intentions regarding suicide-related behavior. Suicide attempts include physical behavior in which an individual attempts to end his or her life, but survives (Kessler et al. 2005). The prevalence of suicidal ideations among youth is estimated as 11.4% in non-care populations and 24.7% in care populations (Evans et al. 2017), which is alarming as it is estimated that more than a third of adolescents who have suicidal thoughts continue to a suicide attempt (Nock et al. 2013). Approximately 11.2% of Dutch adolescents experience suicidal thoughts and 6.6% engage in deliberate self-harm or attempt suicide (Dijkstra 2010).

Given the associations between suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and a completed suicide, it is best to consider the process from suicidal thoughts and ideation to a suicide attempt as a continuum on which the risk for suicide increases as thoughts transform into actions (Joiner 2005). Studies in this field use different synonyms to describe the process before suicide (e.g., suicidal thoughts and behavior [STB], suicidal risk, or suicidality). In this present study, this continuum will be referred to as suicidality. It is crucial to gain more knowledge about markers that contribute to or protect against suicidality so that prevention can focus on identification of adolescents that are particularly at risk of suicidality. This study will examine the association between perfectionism and suicidality, and the moderating role of cognitive coping.

Perfectionism

A personality trait that is strongly predictive for suicidality is perfectionism (Johnson et al. 2011; Smith et al. 2018). Perfectionism is defined as having high standards and being excessively self-critical of one’s behavior (Frost et al. 1990; Hewitt and Flett 1991), and can be divided into two dimensions: personal standards perfectionism (PS) and concerns about mistakes and doubts perfectionism (CMD; Stöber 1998). PS represents the most prominent feature of perfectionism, which is the setting of unreasonably high standards and goals, also conceptualized as self-oriented perfectionism. CMD represents the overly critical evaluations of one’s own behavior, including doubt about actions and overconcerns for mistakes, also conceptualized as socially prescribed perfectionism (Frost et al. 1990; Stoeber and Otto 2006). To make conclusions more comparable, this study will adopt the two-factor model of perfectionism.

The relationship between CMD and suicidality has been studied in both adult and adolescent samples, and CMD proved to be a strong predictor of suicidal ideation (Flett et al. 2014; Hewitt et al. 2006; Roxborough et al. 2012; Shahnaz et al. 2018). Researchers argue that the association between CMD and suicidality may result from a shared symptom, which is a lack of self-disclosure. Adolescents at high risk of suicidality experience difficulties in exposing feelings and communicating thoughts to peers and family; this also applies for socially prescribed perfectionists who tend to hide behind a socially acceptable façade (Horesh et al. 2004). Also, these perfectionists see the world as judgmental and are anxious not to disappoint others, which also makes them prone to suicidal ideation when experiencing interpersonal stressors such as romantic break-ups (Smith et al. 2016).

For a long period, the findings on the relationship between PS and suicidality were mixed (Flett et al. 2014; O’Connor 2007). Some studies report PS as positively related to suicidality (Flamenbaum and Holden 2007; Smith et al. 2018), and others report PS as negatively related (Stoeber and Otto 2006), or unrelated to suicidality (Hewitt et al. 1998, 2014). Recently, a meta-analysis by Smith et al. (2018) gave clarification on the PS and suicidality link, showing that both PS and CMD are related to suicidal ideation. More specifically, PS is associated with suicidal ideation, whereas CMD is associated with both suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.

Striving for success and setting high standards cannot alone predict suicidal ideation, it is the combination with a fear of failure and rigid thinking that puts these individuals at risk for suicidality. This is also reflected in psychological autopsy studies, where the majority of the people that died by suicide had very high expectations and demands of themselves, and any deviation from these standards was seen as a total failure (Center 2007; Kiamanesh et al. 2014; Törnblom et al. 2013). These studies also mentioned that most suicides are committed without a warning. Therefore, researchers warn against conceptualizing PS as healthy or normal perfectionism, because people high in PS try to maintain their invulnerable image and might not show visible signs of distress or suicidality (Hewitt et al. 2003; Smith et al. 2017).

Cognitive Coping

Another factor that is frequently named in theoretical frameworks regarding suicidality is coping, and more specifically cognitive coping. Cognitive coping can be defined as the cognitive strategies people use to manage emotionally arousing stressors (Compas et al. 2001). Coping in the context of suicidality is described as a factor that, when maladaptive, makes it more likely that a feeling of entrapment arises (O’Connor and Kirtley 2018). This is based on studies showing that specific coping strategies such as rumination and limited problem-solving are associated with suicidality (Arie et al. 2008; Morrison and O’Connor 2008; Rogers et al. 2017).

Although there is little research on the relationship between cognitive coping and perfectionism, it seems that when people high in CMD respond to stressors with coping strategies that are considered as maladaptive (e.g., avoidance and rumination), they experience more depressive feelings or distress (Flett et al. 1994; Park et al. 2010). In contrast, when these people use coping strategies that are considered as adaptive (e.g., positive reframing and humor), they experience less distress and more satisfaction (Stoeber and Janssen 2011). In agreement, studies among preadolescents and adolescents, showed that adolescents with high PS and CMD used more dysfunctional coping strategies to cope with stress, and that this contributed to depressive symptoms (Dry et al. 2015; Flett et al. 2012). However, the relationship between perfectionism and coping is unstable. For example, research among adolescent athletes showed that high PS was related to more adaptive coping skills, whereas high CMD was related to poorer coping skills (Mouratidis and Michou 2011).

Yet, research into the relationship between cognitive coping and suicidality is limited, especially in (early) adolescence. Moreover, research into the field of suicidality that includes interaction effects is lacking (Gooding et al. 2015). To our knowledge, the moderating function of coping in the perfectionism—suicidality link, is only examined in a sample of 547 Iranian students from the age of 19–24 (Abdollahi and Carlbring 2017). This study examined adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism in relation to suicidal ideation and the moderating function of coping (task-focused, emotion-focused, and avoidance coping). Coping proved to be a significant moderator. Students high in adaptive or maladaptive perfectionism that used an increased task-focused coping style, were less likely to experience suicidal ideation compared to those with an increased emotion-focused and avoidance coping style. Regarding these results, it would be of added value to replicate this study in a Dutch sample among adolescents.

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between perfectionism and suicidality and the moderating role of cognitive coping. Based on previous research, we expected that more CMD would be associated with an increased suicidality. According to latest meta-analysis of Smith et al. (2018) regarding perfectionism and suicidality, we expected that more PS would be associated with increased suicidality. Furthermore, we expected that for adolescents with high levels of PS and CMD, adaptive coping strategies would buffer against suicidality. The use of maladaptive coping strategies was expected to have a strengthening effect on suicidality.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were 273 adolescents ranging in age from 12 to 15 years (M = 13.54; SD = 0.58) from five secondary schools across the Netherlands. All participants were Dutch speaking and 55.8% were male. The participating schools offered several levels of secondary education: pre-vocational secondary education (41.3%), higher general secondary education (40.9%) and pre-university education (17.9%). School principals gave active consent for schools’ participation. Parents received a letter that explained the purpose and method of the study 1 week before data collection and they gave passive consent. The questionnaire was administered at school during regular class hours. Participation was voluntary and participants were included through passive consent, but were allowed to withdraw from filling in the questionnaire at any point.

Measures

Perfectionism was measured with the Dutch version of the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (Boone et al. 2014; F-MPS; Frost et al. 1990). This 35-item questionnaire consists of six dimensions of perfectionism: personal standard (e.g., ‘I set higher goals than most people’), concern over mistakes (e.g., ‘I hate being less than the best at things’), organization (e.g., ‘I am a neat person’), doubt about actions (e.g., ‘I usually have doubts about the simple everyday things I do’), parental expectations (e.g., ‘My parents set very high standards for me’), and parental criticism (e.g., ‘My parents never tried to understand my mistakes’). Adolescents had to rate statements on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). For the purpose of this study, we derived two dimensions of perfectionism: PS and CMD. PS consists of the sum score of personal standards. CMD consists of the sum score of concern over mistakes and doubt about actions. The reliability and validity of the subscales of the F-MPS has been well established (Boone et al. 2010; Dunkley et al. 2000, 2006). The scales about parental expectations and criticism and organization were excluded because this was beyond the scope of this study. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.77 for PS and 0.85 for CMD.

Suicidality was measured using the VOZZ-screen (Kerkhof et al. 2015). This questionnaire contains 10 questions assessing thoughts and actions about life, self-harm, suicide, and suicidal ideations in the past 7 days. Items about a participant’s life are rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (I totally agree) to 5 (I totally disagree) (e.g., ‘I feel worthless’). Items about self-harm and suicide are rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often) (e.g., ‘I have harmed myself deliberately’). Items about suicidal ideation in the past 7 days are rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (never) to 5 (every day) (e.g., ‘I thought that suicide would be a solution for my problems’). A sum score of 23 or above indicates high risk of suicide. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.74.

Cognitive coping strategies were measured with the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ; Garnefski et al. 2002). This questionnaire consists of nine subscales comprising of four items each. Adolescents had to rate on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a lot) to what extent they had used a particular strategy in response to stressful events. The CERQ contains the following subscales: catastrophizing (e.g., ‘Again and again, I think about how terrible it all is’), acceptance (e.g., ‘I think that I can’t do anything about it’), other blame (e.g., ‘I think that others are to blame’), positive refocus (e.g., ‘I think about nicer things that have nothing to do with it’), positive reappraisal (e.g., ‘I think that I can learn from it’), refocus on planning (e.g., ‘I think of how I can best cope with it’), putting into perspective (e.g., ‘I think that worse things can happen’), rumination (e.g., ‘Again and again, I think about how I feel about it’), and self-blame (e.g., ‘I think that it’s my own fault’). We derived two dimensions for analyses. Maladaptive coping strategies consist of the sum scores of catastrophizing, other blame, rumination, and self-blame. Adaptive coping strategies consist of the sum scores of acceptance, positive refocus, positive reappraisal, planning, and putting into perspective (de Kruijff et al. 2019). The internal consistency of the subscales has proved to be good (Vanderhasselt et al. 2014). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.85 for maladaptive coping strategies and 0.91 for adaptive coping strategies.

Strategy of Analyses

To test the effect of perfectionism on suicidality and the moderating role of cognitive coping on the relationship between perfectionism and suicidality, we preferred to use latent variables. In this way, measurement errors of the latent variables in the regression models were part of the model, ensuring that relations between variables were more valid with greater theoretical meaningfulness (Kline 2010). However, using the individual items (i.e., 10 for suicidality, 13 for CMD, 7 for PS, 16 for maladaptive coping strategies, and 20 for adaptive coping strategies), as indicators for the latent variables, would drastically increase the number of parameters to be estimated and decrease the power of the analysis. Therefore, we used parcels instead of the original items as indicators for the latent variables, and these were computed as the sum of a subset of items of a latent variable. PS was measured by two parcels; all other latent variables were measured by three parcels. The items of a latent variable were allocated to parcels according to the item-to-construct balance method (Little et al. 2002). For each latent variable a one-factor analysis was performed. The item with the highest standardized factor loading was allocated to parcel one, the item with the second highest loading to parcel two and the item with the third highest loading to parcel three. The next three items were allocated to the parcels in reversed order, the item with the fourth highest loading to parcel three, the fifths highest loading to parcel two and the sixth highest loading to parcel one. Then the item with the seventh highest loading to parcel one, the eights highest loading to parcel two, etcetera. In this way the factor structure of the latent variable was reflected in each of the three parcels in an equivalent way. For the analyses we used Mplus (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2015), a software package developed for the analysis of latent variables.

First, means, SDs, and correlations of the research variables are presented in the results section, including a difference test (Wald test) between boys and girls with the help of Mplus. To test the effect of perfectionism on suicidality, and the moderating role of cognitive coping, we used regression analysis with perfectionism, cognitive coping, and the interaction term perfectionism x cognitive coping, as predictors of suicidality. In the first step the effect of perfectionism on suicidality was estimated, in the second step the effect of cognitive coping on suicidality, and in the third step the interaction term was included as predictor of suicidality. Because latent variable interactions were highly non-normal, integration techniques were used in combination with a maximum likelihood estimator with robust standard errors, as described in Klein and Moosbrugger (2000). Fit indices, like CFI and RMSEA, and standardized regression coefficients of interaction terms, were not available for models with latent interaction terms. We tested the significance of the main effects and interaction effects with an (approximate) z-test by dividing the unstandardized regression weight B by the standard error SE(B), resulting in a p value.

Results

First, we tested whether parcels adequately fitted to the data by testing a five factor model. The fit of this five-factor model was good, with CFI = 0.974 and RMSEA = 0.054. The 14 factor loadings varied between 0.72 and 0.91 (M = 0.82, SD = 0.05), indicating substantial loadings. Descriptive characteristics of the variables under study are presented in Table 1. All correlations were significant and positive (p < 0.001), except the correlation of CMD with adaptive coping strategies, and the correlation of adaptive coping strategies with suicidality. CMD and maladaptive coping strategies had substantial correlations with suicidality, while the correlation between PS and suicidality was small. The two perfectionism scales were reasonably interrelated, the correlation between the two coping strategies was a bit lower. PS had moderate correlations with adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies, while CMD was not significantly related with adaptive coping strategies, but substantial with maladaptive coping strategies. The mean score of suicidality falls far below the cut-off for severe suicidality. Eleven adolescents had a score of 23 or above, indicating a high risk for suicidality. Regarding self-harm, 5.5% of the adolescents reported having self-harmed once, and 3.3% several times. Suicidal ideation was experienced by 11.8% of the adolescents and two adolescents reported a suicide attempt.

With the Wald test we tested possible level differences between boys and girls. None of the five tests were significant, indicating no significant difference in mean levels between boys and girls for CMD, PS, maladaptive and adaptive coping strategies, and suicidality. In addition, we tested equality of correlation patterns for boys and girls by comparing the unconstrained covariances with the constrained covariances. The χ2-difference test showed a nonsignificant difference (∆χ2(10) = 16.98, p = 0.075) indicating that the correlational patterns for boys and girls were not significantly different. Although beyond the scope of this study, we also observed the correlations between perfectionism, suicidality, and the single cognitive coping strategies. This correlation table is added as an additional file.

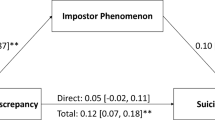

As shown in Table 2, CMD and the interaction between CMD and maladaptive coping were significant predictors of suicidality in Model 1. The significant interaction effect is explored in Fig. 1, in which the predictors were divided into low (one SD below mean) and high (one SD above mean). Under the condition of low maladaptive coping, there was no relationship between CMD and suicidality. However, under the condition of high maladaptive coping, an increase in CMD was associated with an increase in suicidality. In Model 2, CMD and adaptive coping had significant effects on suicidality: more CMD was associated with higher suicidality and more adaptive coping was associated with lower suicidality. The interaction between CMD and adaptive coping was not a significant predictor of suicidality. In Model 3, the initial significant effect of PS on suicidality disappeared in the second and third step. However, maladaptive coping and the interaction between PS and maladaptive coping were significant positive predictors of suicidality. The interaction effect in Model 3 is explored in Fig. 2: under the condition of low maladaptive coping, the relationship between PS and suicidality was decreasing (if PS increased suicidality decreased), under the condition of high maladaptive coping, this relationship was increasing (if PS increased suicidality increased). In Model 4, PS and adaptive coping were significant predictors of suicidality: more PS was associated with higher suicidality and more adaptive coping was associated with lower suicidality. The interaction between PS and adaptive coping was not a significant predictor of suicidality.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to investigate the association between perfectionism and suicidality in early adolescents, and furthermore, the moderating role of cognitive coping on these associations. Based on the literature, it was expected that CMD and PS were positively related to suicidality. Moreover, adaptive coping (i.e., putting into perspective, planning, acceptance, positive refocus, and positive reappraisal) was expected to buffer the relationship between perfectionism and suicidality. Maladaptive coping (i.e., catastrophizing, other blame, rumination, and self-blame) was expected to strengthen the relationship between perfectionism and suicidality. Consistent with the hypotheses, both PS and CMD were positively associated with suicidality. High levels of maladaptive coping in combination with high levels of PS or CMD were associated with an increase in suicidality. Although adaptive coping was related to a decrease in suicidality, adaptive coping in interaction with PS and with CMD was not a significant concurrent predictor of suicidality.

The relationship between perfectionism and suicidality is in line with the meta-analysis of Smith et al. (2018) and findings of other empirical studies (e.g., Flamenbaum and Holden 2007; Roxborough et al. 2012; Smith et al. 2017), in establishing the strong link between perfectionism and suicide. These findings imply that adolescents high in perfectionism might act and think in a way that reinforces suicidal ideation and behavior. Also, the findings were in line with most previous studies (Smith et al. 2018; Zeifman et al. 2020), indicating that PS was associated with an increase in suicidality.

The effect of maladaptive coping on the association between perfectionism and suicidality was in line with previous related studies (Arie et al. 2008; Flett et al. 1994; Morrison and O’Connor 2008; Park et al. 2010; Rogers et al. 2017). Our findings suggest that a high level of maladaptive coping strategies is related to an increase in suicidality in adolescents with high levels of PS or CMD. Consequently, a lower use of maladaptive coping strategies was related to a decreased suicidality, suggesting that techniques aimed at reducing maladaptive coping strategies in perfectionistic adolescents could be helpful in reducing suicidality.

The absent buffering mechanism of adaptive coping strategies in the relationship between perfectionism and suicidality was unexpected. There are some explanations for the lack. First, the use of maladaptive coping might have a greater impact compared to the presence of adaptive coping. For example, one might have a high level of adaptive coping strategies but experience that these skills are overruled by ruminating thoughts. This explanation is partly supported by Thompson et al. (2010) who found that in a sample of depressed women, adaptive coping did not buffer the relationship between maladaptive coping and depressive symptoms. They argue that individuals suffering from depression have more difficulties in using adaptive coping strategies due to the strong intensity of the maladaptive strategies. Others also found that depressed individuals have difficulties in ignoring or prohibiting negative thoughts (De Raedt and Koster 2010). Nonetheless, more research is necessary if this supposed mechanism is to be applied in perfectionistic adolescents in relation to suicidality, because this study represents a non-clinical sample.

Second, an adaptive coping strategy that is frequently found to have a positive effect for individuals displaying suicidality is seeking social support (e.g., Babiss and Gangwisch 2009; Farrell et al. 2015; Trujillo et al. 2017). This specific strategy was not covered by the instrument we used to tap into coping. Other studies have shown that seeking support as a coping strategy would be especially beneficial for perfectionists as they are more likely to experience feelings of loneliness and interpersonal problems (Habke and Flynn 2002; Sherry et al. 2015). We strongly suggest that future studies should include seeking support as a coping strategy when studying the relationship between perfectionism, suicidality, and coping, in order to draw firm conclusions.

Strengths and Limitations

Several limitations of this study must be mentioned. First, the present study did not include an assessment of life stress, which is an important limitation because theoretical models describe perfectionism as a trait that can be harmful when activated by stress (O’Connor and Kirtley 2018; Williams 1997) and we were not able to control for this. Second, the use of a cross-sectional design limits the findings in this study as no conclusion can be made regarding cause and effect. Longitudinal design with multiple assessments over time would be very helpful to define and clarify the causal relationship between perfectionism, coping and suicidality. Furthermore, the present study did not include other important predictors in relation to suicidality, such as depression or hopelessness (Horwitz et al. 2017; Spirito et al. 2003). It would be interesting to investigate the added value of perfectionism next to these predictors to demonstrate the value of targeting perfectionism in prevention and intervention. Also, it would be important to examine how perfectionistic thinking could lead to suicidal ideation. Probably, the presence of rigid thinking in combination with rumination strategies focused on a perfect image of the self will contribute to suicidality by increasing feelings of inadequacy and despair (Flett et al. 1998, 2014). Still, there is limited research on the presence of cognitive rigidity in people with strong perfectionistic characteristics and the relationship with suicidality.

Clinical Implications

The findings in this study stretch the need for more attention to perfectionism in the prevention of suicidality in adolescents. To prevent suicidality in adolescence, it is important to check for perfectionistic traits in adolescents who are in a vulnerable situation and at risk of developing suicidality. People in distress who are characterized by CMD are especially at heightened risk for suicide attempts and specifically these CMD should be considered as a serious risk factor (Smith et al. 2018). In clinical practice, we see that prevention and treatment techniques are often focused on learning new, specifically adaptive, coping skills. Our findings suggest that learning new adaptive coping skills might be insufficient for these adolescents and that a more essential element of prevention and treatment should be learning to exclude or reduce maladaptive coping strategies, which is in line with Horwitz et al. (2011).

Despite the fact that perfectionism is known for its rigid thinking style and, therefore, hard to change, there are several treatment protocols that prove to be effective in reducing unhealthy forms of perfectionism (e.g., Egan et al. 2014). However, the long-term effectiveness of these protocols is unknown. Moreover, treatments that specifically target perfectionism in adolescents experiencing suicidal ideation have not yet been evaluated (Shafran and Mansell 2001). Our study highlights the need for awareness of the risk of perfectionism in adolescents and encourages future studies to discover the clinical relevance of this among adolescents. Research in this age group is especially important as personality traits are developing and becoming more and more stable (McCrae and Costa 1994). This provides an opportunity for prevention and intervention to intervene in this process in order to develop healthy traits.

References

Abdollahi, A., & Carlbring, P. (2017). Coping style as a moderator of perfectionism and suicidal ideation among undergraduate students. Journal of Rational-Emotive Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 35(3), 223–239.

Arie, M., Apter, A., Orbach, I., Yefet, Y., & Zalzman, G. (2008). Autobiographical memory, interpersonal problem solving, and suicidal behavior in adolescent inpatients. Journal of Comprehensive Psychiatry, 49(1), 22–29.

Babiss, L. A., & Gangwisch, J. E. (2009). Sports participation as a protective factor against depression and suicidal ideation in adolescents as mediated by self-esteem and social support. Journal of Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics, 30(5), 376–384.

Boone, L., Soenens, B., Braet, C., & Goossens, L. (2010). An empirical typology of perfectionism in early-to-mid adolescents and its relation with eating disorder symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(7), 686–691.

Boone, L., Soenens, B., & Luyten, P. (2014). When or why does perfectionism translate into eating disorder pathology? A longitudinal examination of the moderating and mediating role of body dissatisfaction. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123(2), 412.

CBS (2018). 1917 zelfdodingen in 2017. Retrieved 07 March 2018 from https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2018/27/1-917-zelfdodingen-in-2017.

Center, A. I. P. (2007). Alaska Suicide Follow-Back Study Final Report. Anchorage, AK: Alaska Department of Health and Social Services.

Compas, B. E., Connor-Smith, J. K., Saltzman, H., Thomsen, A. H., & Wadsworth, M. E. (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127(1), 87.

Horesh, N., Zalsman, G., & Apter, A. (2004). Suicidal behavior and self-disclosure in adolescent psychiatric inpatients. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 192(12), 837–842.

de Kruijff, L. G., Moussault, O. R., Plat, M.-C. J., Hoencamp, R., & van der Wurff, P. (2019). Coping strategies of Dutch servicemembers after deployment. Military Medical Research, 6(1), 9.

De Raedt, R., & Koster, E. H. (2010). Understanding vulnerability for depression from a cognitive neuroscience perspective: A reappraisal of attentional factors and a new conceptual framework. Journal of Cognitive, Affective, Behavioral Neuroscience, 10(1), 50–70.

Dijkstra, M. (2010). Factsheet preventie van suïcidaliteit [Fact sheet]. In http://www.trimbos.nl/webwinkel/productoverzicht-webwinkel/preventie/af/af-factsheetpreventie-van-suicide (Ed.).

Dry, S. M., Kane, R. T., & Rooney, R. M. (2015). An investigation into the role of coping in preventing depression associated with perfectionism in preadolescent children. Frontiers in Public Health, 3, 190.

Dunkley, D. M., Blankstein, K. R., Halsall, J., Williams, M., & Winkworth, G. (2000). The relation between perfectionism and distress: Hassles, coping, and perceived social support as mediators and moderators. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47(4), 437.

Dunkley, D. M., Blankstein, K. R., Masheb, R. M., & Grilo, C. M. (2006). Personal standards and evaluative concerns dimensions of “clinical” perfectionism: A reply to Shafran et al. (2002, 2003) and Hewitt et al. (2003). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(1), 63–84.

Egan, S. J., van Noort, E., Chee, A., Kane, R. T., Hoiles, K. J., Shafran, R., et al. (2014). A randomised controlled trial of face to face versus pure online self-help cognitive behavioural treatment for perfectionism. Journal of Behaviour Research Therapy, 63, 107–113.

Evans, R., White, J., Turley, R., Slater, T., Morgan, H., Strange, H., et al. (2017). Comparison of suicidal ideation, suicide attempt and suicide in children and young people in care and non-care populations: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence. Children Youth Services Review, 82, 122–129.

Farrell, C. T., Bolland, J. M., & Cockerham, W. C. (2015). The role of social support and social context on the incidence of attempted suicide among adolescents living in extremely impoverished communities. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(1), 59–65.

Flamenbaum, R., & Holden, R. R. (2007). Psychache as a mediator in the relationship between perfectionism and suicidality. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(1), 51.

Flett, G. L., Druckman, T., Hewitt, P. L., & Wekerle, C. (2012). Perfectionism, coping, social support, and depression in maltreated adolescents. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 30(2), 118–131.

Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., Blankstein, K. R., & Gray, L. (1998). Psychological distress and the frequency of perfectionistic thinking. Journal of Personality Social Psychology, 75(5), 1363.

Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., & Heisel, M. J. (2014). The destructiveness of perfectionism revisited: Implications for the assessment of suicide risk and the prevention of suicide. Review of General Psychology, 18(3), 156.

Flett, G. L., Russo, F. A., & Hewitt, P. L. (1994). Dimensions of perfectionism and constructive thinking as a coping response. Journal of Rational-Emotive Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 12(3), 163–179.

Frost, R. O., Marten, P., Lahart, C., & Rosenblate, R. (1990). The dimensions of perfectionism. Journal of Cognitive Therapy Research, 14(5), 449–468.

Garnefski, N., Kraaij, V., & Spinhoven, P. (2002). Manual for the use of the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire. Leiderdorp: DATEC.

Gooding, P., Tarrier, N., Dunn, G., Shaw, J., Awenat, Y., Ulph, F., et al. (2015). Effect of hopelessness on the links between psychiatric symptoms and suicidality in a vulnerable population at risk of suicide. Journal of Psychiatry Research, 230(2), 464–471.

Habke, A. M., & Flynn, C. A. (2002). Interpersonal aspects of trait perfectionism. Perfectionisme: Theory, research, and treatment (pp. 151–180). Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Hewitt, P. L., Caelian, C. F., Chen, C., & Flett, G. L. (2014). Perfectionism, stress, daily hassles, hopelessness, and suicide potential in depressed psychiatric adolescents. Journal of Psychopathology Behavioral Assessment, 36(4), 663–674.

Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (1991). Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. Journal of Personality Social Psychology, 60(3), 456.

Hewitt, P. L., Flett, G. L., Sherry, S. B., & Caelian, C. (2006). Trait perfectionism dimensions and suicidal behaviour. In T. Ellis (Ed.), Cognition and suicide: Theory, research and therapy (pp. 215–230). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Hewitt, P. L., Flett, G. L., Sherry, S. B., Habke, M., Parkin, M., Lam, R. W., et al. (2003). The interpersonal expression of perfection: Perfectionistic self-presentation and psychological distress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(6), 1303.

Hewitt, P. L., Norton, G. R., Flett, G. L., Callander, L., & Cowan, T. (1998). Dimensions of perfectionism, hopelessness, and attempted suicide in a sample of alcoholics. Journal of Suicide Life-Threatening Behavior, 28(4), 395–406.

Horwitz, A. G., Berona, J., Czyz, E. K., Yeguez, C. E., & King, C. A. (2017). Positive and negative expectations of hopelessness as longitudinal predictors of depression, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behavior in high-risk adolescents. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 47(2), 168–176.

Horwitz, A. G., Hill, R. M., & King, C. A. (2011). Specific coping behaviors in relation to adolescent depression and suicidal ideation. Journal of Adolescence, 34(5), 1077–1085.

Johnson, J., Wood, A. M., Gooding, P., Taylor, P. J., & Tarrier, N. (2011). Resilience to suicidality: The buffering hypothesis. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(4), 563–591.

Joiner, T. E. (2005). Why people die by suicide. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Kerkhof, A. J. F. M., Huisman, A., Vos, C., & Smits, N. (2015). Handleiding VOZZ & VOZZ screen: Vragenlijst over Zelfdoding. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Borges, G., Nock, M., & Wang, P. S. (2005). Trends in suicide ideation, plans, gestures, and attempts in the United States, 1990–1992 to 2001–2003. JAMA, 293(20), 2487–2495.

Kiamanesh, P., Dyregrov, K., Haavind, H., & Dieserud, G. (2014). Suicide and perfectionism: A psychological autopsy study of non-clinical suicides. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 69(4), 381–399.

Klein, A., & Moosbrugger, H. (2000). Maximum likelihood estimation of latent interaction effects with the LMS method. Psychometrika, 65(4), 457–474.

Kline, R. B. (2010). Promise and pitfalls of structural equation modeling in gifted research. In B. Thompson & R. F. Subotnik (Eds.), Methodologies for conducting research on giftedness (pp. 147–169). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 151–173.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (1994). The stability of personality: Observations and evaluations. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 3(6), 173–175.

Morrison, R., & O’Connor, R. C. (2008). A systematic review of the relationship between rumination and suicidality. Journal of Suicide Life-Threatening Behavior, 38(5), 523–538.

Mouratidis, A., & Michou, A. (2011). Perfectionism, self-determined motivation, and coping among adolescent athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 12(4), 355–367.

Muthén, L., & Muthén, B. (1998–2015). BO 1998–2010. Mplus user’s guide, 6.

Nock, M. K., Green, J. G., Hwang, I., McLaughlin, K. A., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., et al. (2013). Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(3), 300–310.

O’Connor, R. C. (2007). The relations between perfectionism and suicidality: A systematic review. Journal of Suicide Life-Threatening Behavior, 37(6), 698–714.

O’Connor, R. C., & Kirtley, O. J. (2018). The integrated motivational–volitional model of suicidal behaviour. Journal of Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 373(1754), 20170268.

Park, H.-J., Heppner, P. P., & Lee, D.-G. (2010). Maladaptive coping and self-esteem as mediators between perfectionism and psychological distress. Journal of Personality and Individual Differences, 48(4), 469–474.

Rogers, M. L., Schneider, M. E., Tucker, R. P., Law, K. C., Anestis, M. D., & Joiner, T. E. (2017). Overarousal as a mechanism of the relation between rumination and suicidality. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 92, 31–37.

Roxborough, H. M., Hewitt, P. L., Kaldas, J., Flett, G. L., Caelian, C. M., Sherry, S., et al. (2012). Perfectionistic self-presentation, socially prescribed perfectionism, and Suicide in Youth: A test of the perfectionism social disconnection model. Journal of Suicide Life-Threatening Behavior, 42(2), 217–233.

Shafran, R., & Mansell, W. (2001). Perfectionism and psychopathology: A review of research and treatment. Clinical Psychology Review, 21(6), 879–906.

Shahnaz, A., Saffer, B. Y., & Klonsky, E. D. (2018). The relationship of perfectionism to suicide ideation and attempts in a large online sample. Journal of Personality and Individual Differences, 130, 117–121.

Sherry, S. B., Mackinnon, S. P., & Gautreau, C. M. (2015). Perfectionists don’t play nicely with others: Expanding the social disconnection model. Perfectionism, health, and well-being (pp. 225–243). New York: Springer.

Smith, M. M., Sherry, S. B., Chen, S., Saklofske, D. H., Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2016). Perfectionism and narcissism: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Rational-Emotive Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 64, 90–101.

Smith, M. M., Sherry, S. B., Chen, S., Saklofske, D. H., Mushquash, C., Flett, G. L., et al. (2018). The perniciousness of perfectionism: A meta-analytic review of the perfectionism–suicide relationship. Journal of Personality, 86(3), 522–542.

Smith, M. M., Vidovic, V., Sherry, S. B., & Saklofske, D. H. (2017). Self-oriented perfectionism and socially prescribed perfectionism add incrementally to the prediction of suicide ideation beyond hopelessness: A meta-analysis of 15 studies. In U. Kumar (Ed.), Handbook of Suicidal Behaviour (pp. 349–369). New York: Springer.

Spirito, A., Valeri, S., Boergers, J., & Donaldson, D. (2003). Predictors of continued suicidal behavior in adolescents following a suicide attempt. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 32(2), 284–289.

Stöber, J. (1998). The Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale revisited: More perfect with four (instead of six) dimensions. Personality and Individual Differences, 24(4), 481–491.

Stoeber, J., & Janssen, D. P. (2011). Perfectionism and coping with daily failures: Positive reframing helps achieve satisfaction at the end of the day. Jounal of Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 24(5), 477–497.

Stoeber, J., & Otto, K. (2006). Positive conceptions of perfectionism: Approaches, evidence, challenges. Personality Social Psychology Review, 10(4), 295–319.

Thompson, R. J., Mata, J., Jaeggi, S. M., Buschkuehl, M., Jonides, J., & Gotlib, I. H. (2010). Maladaptive coping, adaptive coping, and depressive symptoms: Variations across age and depressive state. Behaviour Research Therapy, 48(6), 459–466.

Törnblom, A. W., Werbart, A., & Rydelius, P.-A. (2013). Shame behind the masks: The parents’ perspective on their sons’ suicide. Archives of Suicide Research, 17(3), 242–261.

Trujillo, M. A., Perrin, P. B., Sutter, M., Tabaac, A., & Benotsch, E. G. (2017). The buffering role of social support on the associations among discrimination, mental health, and suicidality in a transgender sample. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(1), 39–52.

Vanderhasselt, M.-A., Koster, E. H., Onraedt, T., Bruyneel, L., Goubert, L., & De Raedt, R. (2014). Adaptive cognitive emotion regulation moderates the relationship between dysfunctional attitudes and depressive symptoms during a stressful life period: A prospective study. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 45(2), 291–296.

WHO (2018). National suicide prevention strategies: progress, examples and indicators Geneva.

Williams, J. M. G. (1997). Cry of pain. Understanding suicide and self-harm. USA: Penguin Group.

Zeifman, R. J., Antony, M. M., & Kuo, J. R. (2020). When being imperfect just won’t do: Exploring the relationship between perfectionism, emotion dysregulation, and suicidal ideation. Personality and Individual Differences, 152, 109612.

Funding

This paper was supported by a grant of the municipality of Oss, The Netherlands. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KdJH conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination and drafted the manuscript; SR participated in the design, the interpretation of the data and helped to draft the manuscript; AV participated in the design and helped to perform the statistical analyses; RE participated in the design and helped to draft the manuscript; DC participated in the design, the interpretation of the data and helped to draft the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The current submission does not overlap with any other published, in press, or in preparation articles, books, or proceedings and has not been posted on a website. Our research is not under consideration elsewhere and has been conducted in accordance with ethical standards in the field.

Availability of Data

The data for the current study is not publicly available due to them containing information that could compromise research participant privacy, but they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Jonge-Heesen, K.W.J., Rasing, S.P.A., Vermulst, A.A. et al. How to Cope with Perfectionism? Perfectionism as a Risk Factor for Suicidality and the Role of Cognitive Coping in Adolescents. J Rat-Emo Cognitive-Behav Ther 39, 201–216 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-020-00368-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-020-00368-x