Abstract

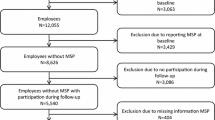

Objective To examine the role of pain experiences in relation to work absence, within the context of other worker health factors and workplace factors among Canadian nurses with work-related musculoskeletal (MSK) injury. Methods Structural equation modeling was used on a sample of 941 employed, female, direct care nurses with at least one day of work absence due to a work-related MSK injury, from the cross-sectional 2005 National Survey of the Work and Health of Nurses. Results The final model suggests that pain severity and pain-related work interference mediate the impact of the following worker health and workplace factors on work absence duration: depression, back problems, age, unionization, workplace physical demands and low job control. The model accounted for 14 % of the variance in work absence duration and 46.6 % of the variance in pain-related work interference. Conclusions Our findings support a key role for pain severity and pain-related work interference in mediating the effects of workplace factors and worker health factors on work absence duration. Future interventions should explore reducing pain-related work interference through addressing workplace issues, such as providing modified work, reducing physical demands, and increasing job control.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

NIOSH. State of the Sector|Healthcare and Social Assistance. Identification of research opportunities for the next decade of NORA: Department of Health and Human Services (National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health [NIOSH]) 2009. Report No.: Report No.: 2009-139.

Frank J, Cullen K; the IWH Ad Hoc Working Group. Preventing injury, illness and disability at work: a view from Canada. A discussion paper for the occupational health and safety community. Scan J Work Environ Health. 2006;32(2):160–7.

Loisel P. Intervention for return to work—what is really effective? Scand J Work Environ Health. 2005;31(4):245–7.

Franche RL, Krause N. Readiness for return to work following injury or illness: conceptualizing the interpersonal impact of health care, workplace, and insurance factors. J Occup Rehabil. 2002;12(4):233–56.

Schultz IZ, Crook JM, Berkowitz J, Meloche GR, Milner R, Zuberbier OA, et al. Biopsychosocial multivariate predictive model of occupational low back disability. Spine. 2002;27(23):2720–5.

Franche RL, Murray E, Ibrahim S, Smith P, Carnide N, Côté P, et al. Examining the impact of worker and workplace factors for prolonged work absences among Canadian nurses. J Occup Environ Med. 2011;53(8):919–27.

Shaw WS, Linton SJ, Pransky G. Reducing sickness absence from work due to low back pain: how well do intervention strategies match modifiable risk factors? J Occup Rehabil. 2006;16:591–605.

Gheldof ELM, Vinck J, Vlaeyen JWS, Hidding A, Crombez G. The differential role of pain, work characteristics and pain-related fear in explaining back pain and sick leave in occupational settings. Pain. 2005;113:71–81.

Allen H, Hubbard D, Sullivan S. The burden of pain on employee health and productivity at a major provider of business services. J Occup Environ Med. 2005;47:658–70.

World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability and health. 2001. www.who.int/icidh.2001.

Collins JJ, Baase CM, Sharda CE, Ozminkowski RJ, Nicholson S, Billotti GM, et al. The assessment of chronic health conditions on work performance, absence, and total economic impact for employers. J Occup Environ Med. 2005;47(6):547–57.

Kessler RC, Barber C, Birnbaum HG, Frank RG, Greenberg PE, Rose RM, et al. Depression in the workplace: effects on short-term disability. Health Aff. 1999;18(5):163–71.

Kessler RC, Greenberg PE, Mickelson KD, Meneades LM, Wang PS. The effects of chronic medical conditions on work loss and work cutback. J Occup Environ Med. 2001;43(3):218–25.

Nordin M, Hiebert R, Pietrek M, Alexander M, Crane M, Lewis S. Association of comorbidity and outcome in episodes of nonspecific low back pain in occupational populations. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44(7):677–84.

Shaw WS, Pranksy G, Fitzgerald TE. Early prognosis for low back disability: intervention strategies for health care providers. Disabil Rehabil. 2001;23:815–28.

Steenstra IA, Verbeek JH, Heymans MW, Bongers PM. Prognostic factors for duration of sick leave in patients sick listed with acute low back pain: a systematic review of the literature. Occup Environ Med. 2004;62:851–60.

Franche RL, Carnide N, Hogg-Johnson S, Côté P, Breslin FC, Bültmann U, et al. Course, diagnosis, and treatment of depressive symptomatology in workers following a workplace injury: a prospective cohort study. Can J Psych. 2009;54(8):534–46.

Tompa E, Scott-Marshall H, Dolinschi R, Trevithick S, Bhattacharyya S. Precarious employment experiences and their health consequences: towards a theoretical framework. Work. 2007;28:209–24.

Alexopoulos EC, Burdorf A, Kalokerinou A. Risk factors for musculoskeletal disorders among nursing personnel in Greek hospitals. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2003;76(4):289–94. doi:10.1007/s00420-003-0442-9.

Bourbonnais R, Mondor M. Job strain and sickness absence among nurses in the province of Quebec. Am J Ind Med. 2001;39(2):194–202.

Koehoorn M, Demers PA, Hertzman C, Village J, Kennedy SM. Work organization and musculoskeletal injuries among a cohort of health care workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32(4):285–93. doi:10.5271/sjweh.1012.

Seago JA. Work group culture, stress, and hostility. Correlations with organizational outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 1996;26(6):39–47.

Verhaeghe R, Mak R, Van Maele G, Kornitzer M, De Backer G. Job stress among middle-aged health care workers and its relation to sickness absence. Stress Health. 2003;19:265–74.

Shields M, Wilkins K, Statistics C, Health C, Canadian Institute for Health I. Findings from the 2005 National Survey of the Work and Health of Nurses. Ottawa: Statistic Canada; 2006.

Crook J, Milner R, Schultz IZ, Stringer B. Determinants of occupational disability following a low back injury: a critical review of the literature. J Occupat Rehab. 2002;12(4):277–95.

van der Hulst M, Vollenbroek-Hutten MMR, Ijzerman MJ. A systematic review of sociodemographic, physical, and psychological predictors of multidisciplinary rehabilitation—or, back school treatment outcome in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine. 2005;30(7):813–25.

Côté P, Hogg-Johnson S, Cassidy D, Carroll L, Frank JW. The association between neck pain intensity, physical functioning, depressive symptomatology and time-to-claim closure after whiplash. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:275–86.

Schade V, Semmer N, Main CJ, Hora J, Boos N. The impact of clinical, morphological, psychosocial and work-related factors on the outcome of lumbar discectomy. Pain. 1999;80(1–2):239–49.

Ash P, Goldstein SI. Predictors of returning to work. Bull Am Acad Psychiatr Law. 1995;23(2):205–10.

Shields M, Wilkins K. Technical Appendix. Findings from the 2005 National Survey of the Work and Health of Nurses. Ottawa, Canada: Statistics Canada; 2006.

Campbell MJ, Julious SA, Altman DG. Estimating sample sizes for binary, ordered categorical, and continuous outcomes in two group comparisons. BMJ. 1995;311:1145–8.

Labour Statistics Division. Work Absence Rates, 2009. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2010.

Labour Statistics Division. Work Absence Rates, 2008. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2009.

Kessler RC, Wittchen H-U, Abelson JM, McGonagle KA, Schwarz N, Kendler KS, et al. Methodological studies of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Int J Meth Psychitr Res. 1998;7(1):33–55.

Karasek RA. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q. 1979;24:285–305.

Siegrist J, Klein D, Voigt KH. Linking sociological with physiological data: the model of effort-reward imbalance at work. [Review] [14 refs]. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1997; 640(Supplementum):112–6.

Karasek R, Brisson C, Kawakami N, Houtman I, Bongers P, Amick B. The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): An instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J Occup Health Psychol. 1998;3(4):322–55.

MacCallum RC, Austin JT. Applications of structural equation modeling in psychological research. Annu Rev Psychol. 2000;51:201–26.

Gorman E, Yu S, Alamgir H. When healthcare workers get sick: exploring sickness absenteeism in British Columbia, Canada. Work. 2010;35(2):117–23.

Buhi ER, Goodson P, Neilands TB. Structural equation modeling: a primer for health behavior researchers. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31(1):74–85.

Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 2004.

Morneau Sobecco. Recommendations for experience rating: For discussion with stakeholders: Morneau Sobeco, 2008.

Elovainio M, Kivimaki M, Vahtera J. Organizational justice: evidence of a new psychosocial predictor of health. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(1):105–8.

Alamgir H, Yu S, Fast C, Hennessy S, Kidd C, Yassi A. Efficiency of overhead ceiling lifts in reducing musculoskeletal injury among carers working in long-term care institutions. Injury. 2008;39(5):570–7.

Schechter J, Green LW, Olsen L, Kruse K, Cargo M. Application of Karasek’s demand/control model to a Canadian occupational setting including shift workers during a period of reorganization and downsizing. Am J Health Promot. 1997;11(6):394–9.

Labriola M, Lund T, Burr H. Prospective study of physical and psychosocial risk factors for sickness absence. Occup Med (Lond). 2006;56(7):469–74. doi:10.1093/occmed/kql058.

Smulders PGW, Nijhuis FJN. The job demands-job control model and absence behaviour: results of a 3-year longitudinal study. Work Stress. 1999;13(2):115–31.

Brouwer S, Franche RL, Hogg-Johnson S, Lee H, Krause N, Shaw WS. Return-to-work self-efficacy: development and validation of a scale in claimants with musculoskeletal disorders. J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21(2):244–58. doi:10.1007/s10926-010-9262-4.

Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, Somerville D, Main CJ. A Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain. 1993;52(2):157–68.

Costa LdCM, Maher CG, McAuley JH, Hancock MJ. Self-efficacy is more important than fear of movement in mediating the relationship between pain and disability in chronic low back pain. Eur J Pain. 2010;15:213–9.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by a research grant provided by the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (Ontario). While the research and analysis are based on data from Statistics Canada, the opinions expressed do not represent the views of Statistics Canada. Peter Smith is supported by a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Nancy Carnide is supported by a Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

10926_2012_9408_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Supplementary Figure 1: Initial theoretical model of worker factors associated with work absence duration due to work-related musculoskeletal injuries. (PDF 48 kb)

10926_2012_9408_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Supplementary Figure 2: Final theoretical model of worker and workplace factors with significant pathways in model-building phase. (PDF 78 kb)

10926_2012_9408_MOESM3_ESM.doc

Supplementary Table 1: Survey items for work absence, worker health factors and workplace factors from the 2005 National Survey of Work and Health of Nurses (DOC 46 kb)

10926_2012_9408_MOESM4_ESM.doc

Supplementary Table 2: Survey item distributions across levels of work absence duration. Proportional distribution by work absence duration, and Chi squared p-values for univariate associations are presented with total sample size for each predictor variable category. (DOC 92 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Murray, E., Franche, RL., Ibrahim, S. et al. Pain-Related Work Interference is a Key Factor in a Worker/Workplace Model of Work Absence Duration Due to Musculoskeletal Conditions in Canadian Nurses. J Occup Rehabil 23, 585–596 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-012-9408-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-012-9408-7