Abstract

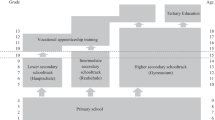

We analyze how life satisfaction changes when adolescents leave school and enter the German vocational and educational training (VET) system. We draw on data from the German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS, Starting Cohort 4) and apply fixed effect regression models. Our findings suggest that leaving school and entering the VET system is associated with an increase in life satisfaction—regardless of the occupational status (i.e., whether the individual is in dual or school-based vocational training or in a vocational preparation program). Moreover, our results provide evidence that adolescents are “happy” to leave school; that having high self-esteem leads to a smaller increase in life satisfaction, and that reaching or failing one’s educational aspirations does not explain changes in life satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This paper uses data from the National Educational Panel Study (NEPS): Starting Grade 9, doi:https://doi.org/10.5157/NEPS:SC4:6.0.0. From 2008 to 2013, NEPS data were collected as part of the Framework Program for the Promotion of Empirical Educational Research funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). Since 2014, NEPS has been conducted under the direction of the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi) at the University of Bamberg in cooperation with a nationwide network.

We estimated models that show only small and non-significant changes of life satisfaction for the states military service (B = 0.06, SE = 0.500, p = 0.900), employment (B = − 0.12, SE = 0.289, p = 0.674), and unemployment (B = 0.01, SE = 0.271, p = 0.960).

We also analyzed the dropout process. The results show that individuals with higher life satisfaction have a lower dropout probability. However, the effect (B = −0.06, SE = 0.009, p < 0.001) is quite small, so that our result should not be biased.

For 9th-graders this was the aspiration from grade 9 and for 10th-graders, from grade 10.

Note that since the effects in the FE model are based on a within-comparison, the value 0 refers to the life satisfaction before individuals reached or failed their aspiration. Therefore, the effect cannot be interpreted as a comparison between individuals who reached their aspiration and those who failed them. Rather the effect shows the change in life satisfaction for individuals who achieved or failed their aspiration.

We also generated categories with other split points (2.5 and 3.5), with similar results.

The effect of x, however, could be biased by time-varying unobserved heterogeneity.

We have no cohort effects due to the sampling design of Starting Cohort 4.

Since the gaps between the life satisfaction measurements varies (12 months between the first three waves and 24 months between waves 3 and 5), we also included splines on a monthly basis in the model (e.g., Singer and Willett 2003, p. 138ff.). These models lead to similar results.

We also used the grade point average of the last school certificate, with similar results.

References

Allison, P. D. (2009). Fixed effects regression models. Los Angeles: Sage.

Allmendinger, J. (1989). Career mobility dynamics: A comparative analysis of the United States, Norway, and West (Germany ed.). Berlin: Sigma.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging Adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist,55(5), 469–480.

Authoring Group Educational Reporting. (2014). Education in Germany 2014. An indicator-based report including an analysis of the situation of people with special educational needs and disabilities. Bielefeld: Bertelsmann.

Bachmann, J. G., O’Malley, P. M., & Johnston, J. (1978). Adolescence to adulthood. Ann Arbor: ISR.

Benson, J. E., & Furstenberg, F. F. (2006). Entry into adulthood: Are adult role transitions meaningful markers of adult identity? In R. MacMillan (Ed.), Advances in life course research (Vol. 11, pp. 199–214). London: Elsevier.

Blossfeld, H.-P., Klijzing, E., Mills, M., & Kurz, K. (Eds.). (2006). Globalization, uncertainty and youth in society. London/New York: Routledge.

Blossfeld, H.-P., Roßbach, H.-G., & von Maurice, J. (Eds.). (2011). Education as a lifelong process. The German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS). Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft: Sonderheft 14. Wiesbaden: VS.

BMBF. (2005). Reform of vocational education and training in Germany. The 2005 vocational training act (Berufsbildungsgesetz 2005). Bonn.

BMBF. (2015). Report on vocational education and training 2015. Bonn.

BMWi. (2016). Vocational training in Germany. Berlin.

Bosch, G., Krone, S., & Langer, D. (Eds.). (2010). Das Berufsbildungssystem in Deutschland. Aktuelle Entwicklungen und Standpunkte. Wiesbaden: VS.

Brüderl, J., & Ludwig, V. (2015). Fixed-effects panel regression. In H. Best & C. Wolf (Eds.), The Sage handbook of regression analysis and causal inference (pp. 327–357). Los Angeles: Sage.

Brunstein, J. C. (1993). Personal goals and subjective well-being: A longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,65(5), 1061–1070.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., & Rodgers, W. L. (1976). The quality of American life: Perceptions, evaluations, and satisfactions. New York: Russel Sage Foundation.

Clark, A. E., Diener, E., Georgellis, Y., & Lucas, R. E. (2008). Lags and leads in life satisfaction: A test of the baseline hypothesis. The Economic Journal,118(529), 222–243.

de Lange, M., Gesthuizen, M., & Wolbers, M. H. J. (2014). Youth labor market integration across Europe. European Societies,16(2), 194–212.

Dew, T., & Huebner, E. S. (1994). Adolescents’ perceived quality of life: An exploratory investigation. Journal of School Psychology,32(2), 185–199.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin,95(3), 542–575.

Diener, E., & Diener, M. (1995). Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,68(4), 653–663.

Diener, E., & Fujita, F. (1995). Resources, personal strivings, and subjective well-being: A nomothetic and idiographic approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,68(5), 926–935.

Diener, E., Inglehart, R., & Tay, L. (2013). Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Social Indicators Research,112(3), 497–527.

Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Scollen, C. N. (2006). Beyond the hedonic treadmill: Revising the adaptation theory of well-being. American Psychologist,61(4), 305–314.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin,125(2), 276–302.

Drentea, P. (2005). Work and activity characteristics across the life course. Advances in Life Course Research,9, 303–329.

Dumont, M., & Provost, M. A. (1995). Resilience in adolescents: Protective role of social support, coping strategies, self-esteem, and social activities on experience of stress and depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,68(4), 653–663.

Eccles, J. S. (2004). Schools, academic motivation, and stage-environment fit. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Adolescent psychology (2nd ed., pp. 125–153). Hobokoen, NJ: Wiley.

Eccles, J. S., & Midgley, C. (1989). Stage-environment fit: Developmentally appropriate classrooms for young adolescents. In C. Ames & R. Ames (Eds.), Research on motivation and education (Vol. 3, pp. 139–181). New York: Academic Press.

Ehrhardt, J. J., Saris, W. E., & Veenhoven, R. (2000). Stability of life-satisfaction over time. Journal of Happiness Studies,1(2), 177–205.

Elder, G. H. (1978). Family history and the life course. In T. K. Hareven (Ed.), Transitions: The family and the life course in historical perspective (pp. 17–64). New York: Academic Press.

Emmons, R. A. (1986). Personal strivings: An approach to personality and subjective well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,51(5), 1058–1068.

Enders, C. K., & Tofighi, D. (2007). Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods,12(2), 121–138.

Erhardt, K., & Künster, R. (2014). Das Splitten von Episodendaten mit Stata: Prozeduren zum Splitten sehr umfangreicher und/oder tagesgenauer Episodendaten. FDZ-Methodenreport, 07/2014.

Fend, H. (1994). Die Entdeckung des Selbst und die Verarbeitung der Pubertät. Bern: Hans Huber.

Fend, H. (1997). Der Umgang mit der Schule in der Adoleszenz: Aufbau und Verlust von Lernmotivation, Selbstachtung und Empathie. Bern: Hans Huber.

Fend, H. (2000). Entwicklungspsychologie des Jugendalters. Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

Finn, J. D. (1989). Withdrawing from school. Review of Educational Research,59(2), 117–142.

Furstenberg, F. F. (2005). Non-normative life course transitions: Reflections on the significance of demographic events on lives. In R. Levy, P. Ghisletta, J.-M. Le Goff, D. Spini, & E. Widmer (Eds.), Towards an interdisciplinary perspective on the life course (Vol. 10, pp. 155–172). Oxford: Elsevier.

Geier, B. (2013). Die berufliche Integration von Jugendlichen mit Hauptschulbildung. Eine Längsschnittanalyse typischer Übergangsverläufe. WSI-Mitteilungen, 66(1), 33–41.

Gilman, R., & Huebner, E. S. (2000). Review of life satisfaction measures for adolescents. Behaviour Change,17(3), 178–195.

Gore, S., Aseltine, R., Colten, M. E., & Lin, B. (1997). Life after high school: Development, stress and well-being. In I. H. Gotlib & B. Wheaton (Eds.), Stress and adversity over the life course: Trajectories and turning points (pp. 197–214). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,85(2), 348–362.

Havighurst, R. J. (1972). Developmental tasks and education (3rd ed.). New York: David McKay Company.

Headey, B., & Wearing, A. (1992). Understanding happiness. A theory of subjective well-being. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire.

Hurrelmann, K. (1987). The importance of school in the life course: Results from the bielefeld study on school-related-problems in adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Research,2(2), 111–125.

Judge, T. A., Bono, J. E., Erez, A., & Locke, E. A. (2005). Core self-evaluations and job and life satisfaction: The role of self-concordance and goal attainment. Journal of Applied Psychology,90(2), 257–268.

KMK (Ed.). (2015). The education system in the Federal Republic of Germany 2013/2014: A description of the responsibilities, structures and developments in education policy for the exchange of information in Europe. Bonn.

Kroh, M. (2006). An experimental evaluation of popular well-being measures (DIW-Discussion Papers No. 546). Retrieved from DIW website. https://www.diw.de/documents/publikationen/73/diw_01.c.43968.de/dp546.pdf.

Krone, S. (2010). Aktuelle Problemfelder der Berufsbildung in Deutschland. In G. Bosch, S. Krone, & D. Langer (Eds.), Das Berufsbildungssystem in Deutschland: Aktuelle Entwicklungen und Standpunkte (pp. 16–36). Wiesbaden: VS.

Krueger, A. B., & Schkade, D. A. (2008). The reliability of subjective well-being measures. Journal of Public Economics,92(8–9), 1833–1845.

Kunter, M., Schümer, G., Artelt, C., Baumert, J., Klieme, E., Neubrand, M., et al. (2002). PISA 2000: Dokumentation der Erhebungsinstrumente (Vol. 72). Berlin: Max-Planck-Institut für Bildungsforschung.

Leven, I., Quenzel, G., & Hurrelmann, K. (2011). Familie. Schule, Freizeit: Kontinuitäten im Wandel. In S. D. Holding (Ed.), Jugend 2010. Eine pragmatische Generation behauptet sich (2nd ed., pp. 53–128). Frankfurt am Main: Fischer.

Levy, R. (1996). Toward a theory of life course institutionalization. In A. Weymann & W. R. Heinz (Eds.), Society and biography: Interrelationships between social structure, institutions and the life course (pp. 83–108). Weinheim: Deutscher Studien Verlag.

Levy, R. (2013). Analysis of life courses: A theoretical sketch. In R. Levy & E. D. Widmer (Eds.), Gendered life courses between standardization and individualization: A European approach applied to Switzerland (pp. 13–36). Zürich/Berlin: LIT.

Lex, T., & Geier, B. (2010). Übergangssystem in der berufliche Bildung: Wahrnehmung einer zweiten Chance oder Risiken des Ausstiegs? In G. Bosch, S. Krone, & D. Langer (Eds.), Das Berufsbildungssystem in Deutschland: Aktuelle Entwicklungen und Standpunkte (pp. 165–187). Wiesbaden: VS.

Lucas, R. E., Clark, A. E., Georgellis, Y., & Diener, E. (2004). Unemployment alters the set point for life satisfaction. Psychological Science,15(1), 8–13.

Ludwig-Mayerhofer, W., Solga, H., Leuze, K., Dombrowski, R., Künster, R., Ebralidze, E., et al. (2011). Vocational education and training and transitions into the labor market. In H.-P. Blossfeld, H.-G. Roßbach, & J. von Maurice (Eds.), Education as a lifelong process: The German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS). Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft: Sonderheft 14 (pp. 251–266). Wiesbaden: VS.

Mansel, J., & Hurrelmann, K. (1994). Außen- und innengerichtete Formen der Problemverarbeitung Jugendlicher: Aggressivität und psychosomatische Beschwerden. Soziale Welt,45(2), 147–179.

Manzoni, A., Härkönen, J., & Mayer, K. U. (2014). Moving On? A growth-curve analysis of occupational attainment and career progression patterns in West Germany. Social Forces,92(4), 1285–1312.

Marsh, H. W. (1990). Self Description Questionnaire (SDQ) II: A theoretical and empirical basis for the measurement of multiple dimensions of adolescent self-concept: An interim test manual and a research monograph. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

Mason, R., & Faulkenberry, G. D. (1978). Aspirations, achievements and life satisfaction. Social Indicators Research,5(1), 133–150.

Maurice, M., & Sellier, F. (1979). A societal analysis of industrial relations: A comparison between France and West Germany. British Journal of Industrial Relations,17(3), 322–336.

Mayer, K. U., & Müller, W. (1986). The state and the structure of the life course. In A. B. Sørensen, F. E. Weinert, & L. R. Sherrod (Eds.), Human development and the life course: Multidisciplinary perspectives (pp. 217–245). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Messersmith, E. E., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2010). Goal attainment, goal striving, and well-being during the transition to adulthood: A ten-year U.S. National Longitudinal Study. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development,2010(130), 27–40.

Michalos, A. C. (1980). Satisfaction and happiness. Social Indicators Research,8(4), 385–422.

Moksnes, U. K., & Espnes, G. A. (2013). Self-esteem and life satisfaction in adolescents—gender and age as potential moderators. Quality of Life Research,22(10), 2921–2928.

NEPS. (2016). Starting Cohort 4: Grade 9 (SC4). Study Overview. Waves 1 to 8. Bamberg.

OECD. (2011). Strong performers and successful reformers in education: Lessons from PISA for the United States. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Ormel, J., Lindenberg, S., Steverink, N., & Verbrugge, L. M. (1999). Subjective well-being and social production functions. Social Indicators Research,46(1), 61–90.

Pallas, A. M. (2007). A subjective approach to schooling and the transition to adulthood. Advances in Life Course Research,11, 173–197.

Proctor, C. L., Linley, P. A., & Maltby, J. (2009). Youth life satisfaction: A review of the literature. Journal of Happiness Studies,10(5), 583–630.

Quoidbach, J., Berry, E. V., Hansenne, M., & Mikolajczak, M. (2010). Positive emotion regulation and well-being. Comparing the impact of eight savoring and dampening strategies. Personality and Individual Differences,49(5), 368–373.

Rabe-Hesketh, S., & Skrondal, A. (2012). Multilevel and longitudinal modeling using Stata. Volume I: Continuous responses. Texas: Stata Press Publication.

Raffe, D. (2014). Explaining national differences in education-work transitions. Twenty years of research on transition systems. European Societies,16(2), 175–193.

Ronen, T., Hamama, L., Rosenbaum, M., & Mishely-Yarlap, A. (2016). Subjective well-being in adolescence: The role of self-control, social support, age, gender, and familial crisis. Journal of Happiness Studies,17(1), 81–104.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton: University Press.

Rosenberg, M. (1979). Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books.

Rutter, M. (1987). Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry,57(3), 316–331.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist,55(1), 68–78.

Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,69(4), 719–727.

Salmela-Aro, K., & Tuominen-Soini, H. (2010). Adolescents’ life satisfaction during the transition to post-comprehensive education: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Happiness Studies,11(6), 683–701.

Schimmack, U. (2009). Well-being. Measuring wellbeing in the SOEP. Schmollers Jahrbuch,129, 1–9.

Schimmack, U., Diener, E., & Oishi, S. (2002). Life-satisfaction is a momentary judgment and a stable personality characteristic: The use of chronically accessible and stable sources. Journal of Personality,70(3), 345–384.

Schimmack, U., & Oishi, S. (2008). The influence of chronically and temporarily accessible information on life satisfaction judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,89(3), 395–406.

Schimmack, U., Schupp, J., & Wagner, G. G. (2008). The influence of environment and personality on the affective and cognitive component of subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research,89(1), 41–60.

Schulenberg, J., O’Malley, P. M., Bachmann, J. G., & Johnston, L. D. (2000). “Spread your wings and fly”: The course of well-being and substance use during the transition to young adulthood. In L. J. Crockett & R. K. Silbereisen (Eds.), Negotiating adolescence in times of social change (pp. 224–255). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schulenberg, J., O’Malley, P. M., Bachmann, J. G., & Johnston, L. D. (2005). Early adult transitions and their relation to well-being and substance use. In R. A. Settersten, F. F. Furstenberg, & R. G. Rumbaut (Eds.), On the frontier of adulthood: Theory research, and public policy (pp. 417–453). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Schwertfeger, A. (2014). Die Bedeutung der Schule für Jugendliche. In J. Brachmann, C. Lübke, & A. Schwertfeger (Eds.), Jugend: Perspektiven eines sozialwissenschaftlichen Forschungsfeldes (pp. 105–118). Bad Heilbrunn: Julius Klinkhardt.

Sheldon, K. M., & Elliot, A. J. (1999). Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,76(3), 482–497.

Sheldon, K. M., & Kasser, T. (1998). Pursuing personal goals: Skills enable progress, but not all progress is beneficial. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin,24(12), 1319–1331.

Singer, J. D., & Willett, J. B. (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Solga, H. (2005). Ohne Abschluss in die Bildungsgesellschaft: Die Erwerbschancen gering qualifizierter Personen aus soziologischer und ökonomischer Perspektive. Opladen: Barbara Budrich.

Solga, H. (2008). Lack of training: Employment opportunities for low-skilled persons from a sociological and microeconomic perspective. In M. Baethge, F. Achtenhagen, & L. Arends (Eds.), Skill formation: Interdisciplinary and cross-national perspectives (pp. 173–204). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Solga, H., & Wagner, S. (2004). Die Zurückgelassenen - die soziale Verarmung der Lernumwelt von Hauptschülerinnen und Hauptschülern. In R. Becker & W. Lauterbach (Eds.), Bildung als Privileg: Erklärungen und Befunde zu den Ursachen der Bildungsungleichheit (pp. 191–219). Wiesbaden: VS.

Stawarz, N. (2013). Inter- und intragenerationale soziale Mobilität. Eine Analyse unter Verwendung von Wachstumskurven. Zeitschrift für Soziologie,42(5), 385–404.

von Collani, G., & Herzberg, P. Y. (2003). Zur internen Struktur des globalen Selbstwertgefühls nach Rosenberg. Zeitschrift Für Differentielle Und Diagnostische Psychologie,24(1), 9–22.

Wood, J. V., Heimpel, S. A., & Michela, J. L. (2003). Savoring versus dampening: self-esteem differences in regulating positive affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,85(3), 566–580.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Massachusetts: MIT press.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the support and helpful comments of Oliver Arránz Becker, Jacqueline Klesse, Daniel Lois, Wolfgang Ludwig-Mayerhofer, Veronika Salzburger, and Sophie Straub in preparing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Siembab, M., Stawarz, N. How Does Life Satisfaction Change During the Transition from School to Work? A Study of Ninth and Tenth-Grade School-Leavers in Germany. J Happiness Stud 20, 165–183 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9945-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9945-z