Abstract

The purpose of this descriptive study was to explore factors associated with perceptions of grandparent responsibility for grandchildren in three-generation households, focusing especially on a comparison of grandparents’ and parents’ financial contributions to the household and ethnicity of grandparent(s). The analysis used information about three-generation families in the 2011–2015 American Community Survey, retrieved through the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series. In 30% of these families, grandparents said they were “primarily responsible” for the grandchildren, even though the child’s parent was also in the household. Logistic regression models showed that grandparents who contributed a larger share of household income and grandparents who were householders were significantly more likely to report being primarily responsible for grandchildren in three-generation households, suggesting that the distribution of financial resources (or resource balance) within the household was associated with perceptions of responsibility. However, grandparents’ race and ethnicity moderated this association, indicating that cultural norms may intersect with resources in shaping these reports. The findings suggest that perceived responsibilities of grandparents in three-generation households may be shaped by the balance of financial resources among household members, but also by cultural norms of grandparenting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Three-generation families, including minor children, parent(s), and grandparent(s), have been on the upswing in the United States (Casper et al., 2016; Dunifon et al., 2014). Estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau indicate that in 2014, 3.2 million children under the age of 18 lived with a grandparent and one or more parents, representing a 37% increase from two decades previously (U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, n.d.) Factors contributing to the establishment of intergenerational households include the high cost of housing, economic insecurity among young families as well as among aging family members, and needs for assistance across generations associated with childcare, health limitations, or other forms of support (Burr & Mutchler, 2007; Pilkauskas & Cross, 2018). Cultural orientations impacting intergenerational roles and relationships also have contributed to household configurations (Casper et al., 2016; Harrington Meyer & Kandic, 2017; Silverstein & Lee, 2016; Silverstein et al., 2012), resulting in higher prevalence of intergenerational households among some racial and ethnic groups than others. Along with changes in longevity, fertility, and marriage that are reshaping our understanding of “family” (Seltzer, 2019), these factors have led to increasing numbers of intergenerational co-resident families and growing heterogeneity in the relationships and responsibilities embedded within them.

The purpose of this paper was to explore the factors associated with grandparents reporting responsibility for grandchildren within three-generation households in the US. This study was motivated by scientific questions about intergenerational support in families, as well as by policy and advocacy interests in grandparent caregivers. In this study we drew on responses to a question in the American Community Survey asking if adults were responsible for grandchildren living with them. In considering factors associated with grandparent responsibility, our analysis focused on the distribution of resources within the household and on the racial and ethnic characteristics of the grandparent, two sets of factors that have been heavily featured in the intergenerational family literature.

This topic has taken on new significance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Exposure of older adults to COVID-19 infection may be higher in multigenerational homes due to household density, economic circumstances, and work patterns of adults (Stokes & Patterson, 2020). Indeed, the rate of intergenerational co-residence is positively associated with COVID-19 fatalities in the US as well as the EU (Aparicio Fenoll & Grossbard, 2020). Even absent a pandemic, multigenerational living may have mixed consequences for families. For example, single mothers and their children may benefit financially from living with grandparents (Mutchler & Baker, 2009), while adults (and especially women) who assume caregiving responsibilities for older relatives (Smith et al., 2020) or grandchildren (Harrington Meyer & Herd, 2007) experience elevated risks of employment disruptions.

Background

Factors Shaping the Prevalence of Three-Generation Households

Three-generation co-residential families have been more common in the US than in many European countries (Glaser et al., 2018; Pilkauskas & Martinson, 2014), but less common than in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean (United Nations, 2019). In the US, socioeconomic disadvantage has been a key factor promoting intergenerational living (Cross, 2018; Dunifon et al., 2014; Pilkauskas, 2012; Wiemers, 2014). Recent reports have documented an increase in the number of multigenerational households in the US (Casper et al., 2016; Glaser et al., 2018), which has been linked to amplified economic pressures on families that may be eased through shared resources. Ethnicity and immigration status have also been linked to intergenerational households, and some cultural groups have been more receptive than others to intergenerational living as a means of providing mutual support (Luo et al., 2012; Pilkauskas, 2012). Factors shaping rates of multigenerational living in the US compared to other countries have been thought to include the relatively higher rate of teenage births in the US (Sedgh et al., 2015), child welfare policies that promote grandparent care and multigenerational living (Baker et al., 2008; Harrington-Meyer & Kandic, 2017), immigration policies giving preference to family reunification, and immigration flows that have been dominated by arrivals from relatively “familistic” societies (i.e., Asia and Latin America). In light of these demographic and policy factors, the US is an important focus for this work.

Three-generation families may reflect strategic responses to needs for mutual assistance within the intergenerational family system (Silverstein et al., 2012). For example, a three-generation household may serve as a vehicle for providing assistance to a member of the grandparent generation who is frail or in need of assistance; in many of these cases, the grandparent may contribute to the household financially or by providing childcare. Three-generation households may also be established in response to members of the parent generation who are too young, economically insecure, or otherwise unable to provide adequate support for their own children (Casper et al., 2016; Goodman & Silverstein, 2002; Pilkauskas, 2012; Pilkauskas & Cross, 2018). Mutual assistance may occur in these settings as well, through the pooling of economic resources, time, and instrumental support across generations (Harrington Meyer & Kandic, 2017). Culturally distinctive norms and values have also contributed to differences in the prevalence of three-generation households across demographic groups (Choi et al., 2016; Fuller-Thomson et al., 1997; Pilkauskas, 2012; Pilkauskas & Cross, 2018; Silverstein et al., 2012), resulting in patterns that differ by race, ethnicity, and immigrant status.

Grandparents’ Contributions within the Three-Generation Household

Contents of the grandparent role are diverse across families and settings (Hayslip et al., 2017). While many grandparents provide substantial support to their grandchildren without living together, the literature points to the shared household as a setting in which the contributions of grandparents may be especially substantial, including financial support, hands-on caregiving, help with homework, and other forms of care. Themes of reciprocity and obligation both across and within households are prevalent in the literature on intergenerational families (Drake et al., 2018; Johar et al., 2015). For example, many young adult children continue to live with and receive financial support from their parents (Padgett & Remle, 2016). For some families, continued financial support for adult children may extend to financially supporting or physically caring for grandchildren in the multigenerational home. Multiple “currencies” of exchange may be operational in a mutual assistance model—for example, financial assistance on the part of the grandparent generation may be balanced by instrumental assistance on the part of the parent generation, or vice versa.

Considerable policy and advocacy efforts are directed toward strengthening support for families in which grandparents take on responsibility for minor grandchildren. Yet the conceptualization and measurement of caregiver status among grandparents is often unclear. To facilitate conceptualization and measurement of grandparents who are responsible for their grandchildren, questions about grandparents as caregivers have been included in the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS) for the last two decades in an effort to help understand provisions needed for federal programs designed to assist families.Footnote 1 The questions, asked of all respondents age 30 or older, are as follows:

26a. Does this person have any of his/her own grandchildren under the age of 18 living in this house or apartment? (Yes/no)

26b. [If yes] Is this grandparent currently responsible for most of the basic needs of any grandchildren under the age of 18 who live in this house or apartment? (Yes/no)

An additional question is asked about the length of time for which caregiving grandparents have been responsible for coresiding grandchildren.

Although policy and advocacy around grandparents who are responsible for grandchildren typically refer to “skipped-generation” families in which the grandchild lives with the grandparent in the absence of their parents, statistical reports make clear that many grandparents in three-generation households describe themselves as primary caregivers to a grandchild. Indeed, between 61 and 68% of grandchildren who are in the primary care of a grandparent live in three-generation households.Footnote 2 In thinking about their responsibility for coresident grandchildren, grandparents may consider a mix of factors, including the extent to which they provide hands-on childcare, financial support, cultural roles, and potentially other factors that shape ways in which adults in three-generation families work together to provide support for grandchildren. The question of what factors are associated with grandparents in these three-generation families being responsible for their grandchildren is thus an important question.

Our analysis focused on two sets of factors that have been featured in the intergenerational family literature. First, we explored the association between the distribution of financial resources across generations in the household and reports of grandparent responsibility. We hypothesized that grandparents in three-generation families would be more likely to be responsible for their grandchildren when their financial contributions were more sizable relative to that of the grandchild’ parent(s), measured by the share of the three-generation family income contributed by the grandparent (Hypothesis 1a). Using the same rationale, we expected grandparents would be more likely to be responsible for the grandchild when they were the householder (Hypothesis 1b).

The second factor we considered in this paper is the racial and ethnic characteristics of grandparents, which may shape how they think about responsibilities toward other family members. “Cultural templates” defining family roles, intergenerational relationships, and caregiving norms (Arber & Timonen, 2012; Choi et al., 2016; Goodman & Silverstein, 2002; Herlofson & Hagestad, 2012; Luo et al., 2012; Silverstein & Lee, 2016) yield diverse household settings along with embedded relationships and responsibilities. High rates of intergenerational co-residence among African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians, for example, are frequently attributed to a combination of resource issues and cultural values and expectations. We expected that grandparents from ethnic groups having stronger cultural norms relating to significant grandparent roles (specifically, African American, Latino, and Asian grandparents) also may be more likely to perceive responsibility for the grandchildren in three-generation households (Hypothesis 2). Cultural templates may also interconnect with unevenness in financial contributions. Groups with stronger cultural patterns of multigenerational living and stronger norms surrounding grandparent contributions to care and support of grandchildren would be expected to draw on factors that go beyond financial support when describing responsibility for grandchildren. Therefore, we hypothesized that among groups in which substantial grandparent caregiving is more common, the associations between grandparents’ providing more of the household resources and their being responsible for grandchildren were dampened (Hypothesis 3).

Gaps and Contributions

This paper fills a gap in the literature on grandparents’ experiences within multigenerational families. Prior literature has not addressed the question of what factors account for grandparents’ perceiving responsibility for grandchildren when the child’s parent also lives in the household. Although the current study was correlational and we could not infer causation, this paper offered unique findings about how grandparents’ holding more financial resources in the household relative to the parents, in terms of income or household headship, may be factored in when responsibility is considered. It also identified intriguing differences in propensities for taking responsibility across racial and ethnic groups. This analysis on grandparent caregiving contributed to a more comprehensive scientific understanding of the matrix of family relationships that is growing increasingly complex. As well, it added to a knowledge base essential for the development and evaluation of many programs and services meant to assist grandparent caregivers (U.S. Census Bureau, n.d.). This study made a unique contribution to both of these goals.

Data, Measures, and Methods

Data

We analyzed factors shaping reports of grandparents’ responsibility for grandchildren in three-generation households using information from the American Community Survey (ACS). The ACS has been conducted on an annual basis by the U.S. Census Bureau, providing demographic, social, economic, and housing information. Our analysis used the 2011–2015 ACS microdata file obtained through the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) (Ruggles et al., 2017), which corresponded to a 5% nationally representative sample including about 3.1 million total observations. For convenience, and because all financial data in this five-year file was expressed in 2015 dollars, we referred to the data as ACS 2015.

The IPUMS data system included flags linking the co-resident spouse, mother, and father of each respondent, allowing relationships to be more clearly specified. For our study, three-generation family households were the unit of observation, and each case contained information about all three generations. Our final sample included 177,858 three-generation family households including at least one minor child (younger than 18), one or both of their grandparents, and one or both of their parents.

Variables

As noted above, in the ACS, every adult age 30 or older was asked if they had any grandchildren under the age of 18 living in the same home. Those who responded in the affirmative were asked if they were “currently responsible for most of the basic needs” of those grandchildren. These questions do not offer respondents a clear definition of “responsibility” in this context, and respondents therefore draw on their own interpretations and perceptions. In this study, the dependent variable was dichotomous, where 1 = grandparent was reported as being responsible and 0 = grandparent was not reported as being responsible. In households where both grandparents were present, and one or both of them reported being responsible for grandchild(ren), the couple was classified as being responsible.

We considered two sets of variables associated with reports of responsibility for grandchildren among grandparents in three-generation households to test our hypotheses. The first set was captured by share of household income contributed by the grandparent, and by household headship. We calculated the percentage of household income contributed by the grandparent(s), which ranged from 0% (representing three-generation co-resident household in which all of the income was generated by the parent generation) to 100% (reflecting households in which all the income was generated by the grandparent generation). A second indicator used was householder status, reflecting the person who owns or rents the home in which the three-generation family lives (1 = the grandparent(s) was householder, 0 = the grandparent(s) was not the householder). Our analysis also took into account grandparent’s income (logged) as a resource indicator.

Additional variables were created to capture cultural factors shaping grandparent support and contributions to their grandchildren. Dummy variables were established based on race and ethnicity reported by the grandparent to capture potential cultural factors shaping grandparent responsibility. Categories included non-Hispanic Whites, Hispanic (any race), non-Hispanic African American, non-Hispanic Asian, and non-Hispanic “other” race. The “other” race category included those who report American Indian or Alaska Native origin, some other race, and more than one race; it also included grandparent couples in which the spouses reported different races. Non-Hispanic Whites served as the reference group.

Additionally, control variables included family characteristics that may affect perceptions of grandparent responsibility in three-generation households, including characteristics of the grandparent, parent, and grandchild generations. With respect to grandparent characteristics, we included English proficiency and number of years since immigrating to the US, which have been shown to be important correlates of intergenerational living arrangements; they also reflected aspects of acculturation relevant to family roles and relationships (Abdul-Malak, 2016; Silverstein & Lee, 2016). We included variables indicating how many grandparents were in the household, and if only one grandparent was present, we indicated whether the grandparent was male or female. We also included age of grandparent(s) (mean age of grandparents if both are present) and grandparent(s) disability status (0 = no disability, 1 = one or both grandparents had a disability).

Covariates capturing parent characteristics included attributes that may further contribute to the extent to which grandparent care and support was required. These included number and gender of parents (father only, mother only, or both parents), parents’ age in years (mean age of parents if both were present), parent disability status (0 = no disability, 1 = one or both parents had a disability), and parents’ school attendance (0 = not in school, 1 = one or both parents was in school). Finally, we controlled for size and age composition of the grandchild cohort living in the household by including number of grandchild(ren) under age 18 (dummy variables for 1, 2, 3, and 4 or more grandchildren present) and age of grandchild(ren) (captured by dummy variables indicating that one or more grandchildren was age 5 or under, one or more grandchildren age 6 to 12, and one or more grandchildren age 13 to 17; note that these indicators are not mutually exclusive).

As shown in Table 1, grandparents were reported as being responsible for the grandchildren in three out of ten families among the three-generation family households identified for this study. Grandparents were the householder in a majority of the three-generation families (66%). The median income of grandparents in these three-generation family households was low, at roughly $17,500 in 2015 dollars (in comparison, median income for all U.S. households in 2015 was $55,775; U.S. Census Bureau, n.d.). Yet grandparents contributed a majority of the household income, with a median of 57% contributed by the grandparent generation. Just under half of the grandparents in the population defined for this study were non-Hispanic and White, while 16% were non-Hispanic Black, 9% were non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander, and 25% were Hispanic. The remaining 5% were not Hispanic, but the grandparent reported some other race, reported being multi-racial, or, in the case of two grandparents being present, the two grandparents reported different races.

Nearly two-thirds of the grandparents spoke English only at home, and nearly seven out of ten were U.S. citizens by birth. While 40% of the grandparent generation was made up of a couple, 49% of the households included just the grandmother, and 11% included only a grandfather. In one-third of the households, one or both grandparents had a disability. Median age of the grandparent generation was 60.

Characteristics of the parent generation, also shown in Table 1, indicated that in half of the three-generation co-resident families considered here, only the mother was present. However, in one-third of the families, both parents were present, and 17% included fathers only. In 9% of the families, one or both parents had a disability, and in 17% one or both parents were in school. The median age of the parent generation in these households was 33 years. Most of the three-generation families included just one grandchild (54%), while 30% included two grandchildren, 11% included three, and 5% included four or more grandchildren. More than half of the families included at least one preschool-age grandchild (age 5 or under), and 47% included at least one grandchild age 6–12. Twenty-seven percent included one or more grandchildren who were teenagers age 13–17.

The bivariate association between grandparent reports of responsibility and race or ethnicity showed that the share of grandparents reporting responsibility for a grandchild within a three-generation household was highest among those who reported other or mixed-race backgrounds, at 42% (see Table 2), and among African American grandparents, at 35%. Asian/Pacific Islander grandparents and Hispanic grandparents were less likely to report responsibility for grandchildren, at 14% and 25%, respectively. Nearly one-third of non-Hispanic White grandparents in three-generation family households reported responsibility for grandchildren.

Empirical Strategy

Logistic regression models were estimated using a hierarchical inclusion of variables strategy. The first model evaluated the direct associations between the characteristics of grandparents, parents, and grandchildren, and grandparent’s reports of responsibility. Two additional models considered whether the associations between resource balance on grandparent reports of responsibility were different across race and ethnic groups. As a means of illustrating results associated with these interactive models, we estimated the predicted probabilities of grandparents reporting responsibility for grandchildren in three-generation households. All results were based on weighted data, using centered household weights.

We focused on the share of income contributed by the grandparent and household headship to assess the financial contributions to the household made by the grandparent in relation to the parent. We used logistic regressions in SPSS to perform our estimations (see Eq. 1) based on weighted data.

Here, \(P\left(Y\right)\) was defined as the probability of reporting primary responsibility for grandchildren among grandparents in three-generation family households. \(P\left(Y\right)\) ranges from 0 to 1. The factors associated with the probability of grandparents’ reporting responsibility for grandchildren (independent variables) were represented in the right side of the equation by \({x}_{1}\) to \({x}_{n}\). In logistic regression, \(\frac{P(Y)}{1-P(Y)}\) is known as the odds ratio, and the coefficients \({b}_{1},\dots {,b}_{n}\) indicate the change in the expected log odds with respect to a one unit change in \({x}_{1},\dots {,x}_{n}\), respectively.

We expected that grandparents would more commonly report primary responsibility for grandchildren when resources of the grandparent(s) were large relative to those of the parent(s), within the three-generation family household. We focused on the share of income contributed by the grandparent and household headship in making this assessment. We discussed the results using odds ratios (Eq. 2) rather than the log odds because we considered it a more intuitive way of describing the association between the variables of interest.

We anticipated that grandparents from race and ethnic groups having stronger cultural norms relating to significant grandparent roles would be more likely to report responsibility for their grandchildren in three-generation households. As well, we hypothesized that among race and ethnic groups in which the grandparent caregiving role was more familiar, the association between financial resource balance and grandparents’ reporting responsibility for grandchildren was dampened. We estimated interactions between the race and ethnicity of the grandparent and their financial resources in two independent models, one for share of income contributed by the grandparent and one for household headship to test that hypothesis. We estimated predicted probabilities (Eq. 3) for the figures describing the results of the interacted models.

Results

Consistent with our first hypothesis, financial resources were associated with the likelihood that grandparents report responsibility for grandchildren in three-generation families (see Table 3). Net of grandparents’ income, grandparents who contributed a larger share of household income were significantly more likely to report being responsible for grandchildren. In addition, grandparents who were householders were more likely to report responsibility for their grandchildren. Together, these results suggest that grandparents’ reports of responsibility were more likely in households where they were contributing more of the resources relative to the parent generation.

Significant differences were also noted for race and ethnicity of grandparents, with Asian/Pacific Islander grandparents and “other” race grandparents being more likely to report being responsible for grandchildren, and Hispanic grandparents being less likely to have done so.Footnote 3 No significant difference between Black/African American and non-Hispanic White grandparents was detected once other factors were controlled. Thus partial support for Hypothesis 2 was found. Note that the coefficients shown in Table 3 were estimated net of the complete set of covariates described in Table 1 (see footnote to Table 3).

Two additional models tested interactions of race/ethnicity with the share of income contributed by the grandparent (Model 2) and with householder status (Model 3). Results suggested that the association between income share contributed by grandparents and grandparent reports of responsibility was smaller for grandparents who were Black, Asian, or Hispanic. Model 3 suggested further that the association between the grandparent being the householder and grandparent reports of responsibility was smaller for grandparents who were Hispanic or Asian.

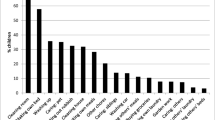

The implications of these results were illustrated in Figs. 1 and 2. Figure 1 was generated from coefficients in Model 2, and reflected the probability of a grandparent being reported as responsible for grandchildren based on a “prototypical” three-generation household, defined here as being composed of a single grandmother, age 60, who only spoke English at home, was U.S. born, did not have a disability, was the householder, and had income of $17,495, living with her single daughter who was age 33, not disabled, and not in school, along with one preschool-age grandchild. The estimates conveyed that all else equal, the probability of a grandparent reporting responsibility for grandchildren was substantially higher in households where grandparents contributed more of the financial resources, but this differed across race and ethnic groups. For example, non-Hispanic White grandparents, in households where they contribute 20% of the income (representing one standard deviation below the mean), had a 14% probability of assuming responsibility, but this probability was almost 40% among White grandparents contributing 88% of the income (representing one standard deviation above the mean), nearly a three-fold increase in predicted probability for this group. The curves were flatter for the other groups, suggesting that resource balance mattered less for these groups than for non-Hispanic Whites. For example, non-Hispanic Asian grandparents contributing a small share of household income had a 22% predicted probability of reporting responsibility—considerably higher than among non-Hispanic White grandparents contributing a similar share toward household income—but among Asian grandparents contributing a large share of the resources, the probability rose just to 34%, only 1.5 times the predicted probability for Asians contributing a small share. These results made clear that resources matter among all these groups, but to different degrees.

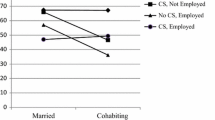

Figure 2 illustrated that being the householder in a three-generation family is also associated with a grandparent’s likelihood of reporting responsibility for grandchildren in different ways across race and ethnic groups. In particular, the positive coefficient for householder status was significantly reduced among Hispanic and Asian grandparents, consistent with findings based on the balance of financial resources reported here. We conclude that as expected, families described the grandparent contributions as they played out in multigenerational families in culturally unique ways, likely drawing on distinctive norms, experiences, and understandings of responsibility.

Discussion

The grandparent role has been discussed extensively in recent decades with respect to its implications for theory, policy, and practice. Many grandparents routinely provide emotional support and occasional babysitting for their grandchildren, and a sizable share offer financial assistance to their children and grandchildren, sometimes sharing a home or providing custodial care when parents are unable to do so. The three-generation household, including grandparents, parents, and grandchildren living together, represents a setting in which grandparent contributions may be especially substantial.

This paper contributed to filling an important gap in the literature relating to multigenerational families and grandparent contributions within them. Our findings illustrated that in three out of ten three-generation households including grandparents and minor children, grandparents reported primary responsibility for the grandchildren with whom they live, even though the child’s parent(s) were also present. Our study focused on two primary mechanisms that may contribute to this outcome and illustrated the importance of both economic resources and cultural factors. Theoretical concepts of exchange and reciprocity suggest that adults reflect on the resource balance in the household in describing grandparent contributions. This expectation was supported by our finding that net of the demographic characteristics of grandparents, parents, and children, grandparents were more likely to report being responsible for grandchildren when they contributed more resources to the household, as reflected by share of income and household headship. Yet race and ethnicity of the grandparent clearly had an association that transcended financial exchanges, potentially reflecting cultural differences in how grandparent contributions were described, responses to immigrant experiences, needs of parents for support and assistance, or other factors. We found that all else equal, grandparents who were Asian/Pacific Islander were more likely to report being responsible for grandchildren, while those who were Hispanic were significantly less likely. Moreover, we found that grandparents from different racial and ethnic backgrounds responded differently to economic resources. These findings highlighted the heterogeneity of grandparent contributions within three-generation families. Advances in research and policy are needed to adequately understand and support intergenerational families and the children embedded within them.

Limitations and Future Research

Some limitations of this research require mention. First, the questions in the American Community Survey serving as the basis for this study do not allow elaboration on what respondents really mean when they say that a grandparent is “responsible” for grandchildren in the home. Our findings suggest that resource distribution and cultural norms are associated with responses to this question; however, additional factors, such as time spent with the grandchild or the amount of hands-on care provided, may also factor into these responses. The data used for this study do not permit determining whether grandparents who report being primarily responsible for a grandchild in the household has actually assumed financial responsibility for the child. Second, the reported assessment of grandparent responsibility in these data may or may not reflect a consensus across household members. The American Community Survey is a household survey meant to collect data on everyone living in the household, but in many households, it is likely that one person responds on behalf of everyone living in the home. Assessment of responsibility may differ depending on who responds to the questionnaire, a factor inviting further consideration using an alternative data source that allows the respondent to be identified, which the ACS does not. A third limitation of the study is that no information is provided on non-economic exchanges that occur in the three-generation households under study. Thus we are not able to determine whether three-generation grandparents who report being responsible for grandchildren are also providing, or receiving, other types of resources. As a fourth limitation, we note that households could also include additional adults who contribute financially to the household. Although we do not believe this would impact our results, it is a potentially interesting question for future research. In addition, the data used in this paper reflect a single five-year time period (2011–2015) and data from earlier or subsequent years could yield slightly different findings. Finally, this paper is based on correlational evidence that may not reflect causal processes underlying behavior and reports of grandparental responsibility.

Despite these limitations, these intriguing findings raise many questions for future research. Further study could focus on the extent to which three-generation grandparents who perceive themselves to be primarily responsible for co-resident grandchildren have a different type or quality of relationship with the grandchildren in their care. Also requiring investigation is the durability of this status. The data used here reflect a cross-sectional assessment of the composition of households and the embedded relationships and responsibilities. Yet these features may be fluid; for example, some parents in three-generation households may be relatively unstable household members, moving in and out as circumstances change, with the grandparent assuming responsibility on a more permanent basis. Understanding the extent to which grandparents reporting responsibility for grandchildren in the three-generation setting reflects this fluidity would be informative. Also informative could be an in-depth analysis of how ages of the grandchildren are associated with grandparents’ reporting responsibility for them. Although this question is beyond the scope of our current study, our analysis indicates that in families with a grandchild age 5 or under, grandparents were less likely to report responsibility for grandchildren (results not shown). Very young children require more monitoring and more hands-on care, yet respondents in this study were less likely to identify being “responsible” for grandchildren when preschool-age grandchildren were present. Deepening our understanding of the stability of three-generation households, and how the movement of members in and out of the household is associated with responsibilities and relationships, is an important step in advancing the literature.

Notes

Calculated by the authors from Table B10002 of the American Community Survey for 2011–2019.

In light of the low percentage of Asian American grandparents who reported responsibility for grandchildren within three-generation households (see Table 2), it is perhaps surprising that the multivariate results suggest that Asian American grandparents were significantly more likely to have reported responsibility than are their non-Hispanic White counterparts, all else equal. Close investigation of this result showed that a key factor shaping this result was the high presence of both parents within Asian three-generation households. Three out of four 3-generation households among Asian Americans included both parents in the middle generation, compared to one-third or fewer of the families in the other groups considered. This scenario suppressed the prevalence of grandparent responsibility among Asian Americans in bivariate comparisons.

References

Abdul-Malak, Y. (2016). Health and grandparenting among 13 Caribbean (and one Latin American) immigrant women in the United States. In M. Harrington Meyer & Y. Abdul-Malak (Eds.), Grandparenting in the United States (1st ed., pp. 61–80). Routledge.

Aparicio Fenoll, A., & Grossbard, S. (2020). Intergenerational residence patterns and Covid-19 fatalities in the EU and the US. Economics and Human Biology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2020.100934

Arber, S., & Timonen, V. (2012). Grandparenting in the 21st century: New directions. In S. Arber & V. Timonen (Eds.), Contemporary grandparenting: Changing family relationships in global contexts (1st ed., pp. 247–64). The Policy Press.

Baker, L. A., Silverstein, M., & Putney, N. M. (2008). Grandparents raising grandchildren in the United States: Changing family forms, stagnant social policies. Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 7, 53–69.

Burr, J. A., & Mutchler, J. E. (2007). Residential independence among older persons: Community and individual factors. Population Research and Policy Review, 26, 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-007-9022-0

Casper, L. M., Florian, S. M., Potts, C. B., & Brandon, P. D. (2016). Portrait of American grandparent families. In M. Harrington Meyer & Y. Abdul-Malak (Eds.), Grandparenting in the United States (1st ed., pp. 109–132). Routledge

Choi, M., Sprang, G., & Eslinger, J. G. (2016). Grandparents raising grandchildren: A synthetic review and theoretical model for interventions. Family and Community Health, 39(2), 120–128.

Cross, C. J. (2018). Extended family households among children in the United States: Differences by race/ethnicity and socio-economic status. Population Studies, 72(2), 235–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2018.1468476

Drake, D., Dandy, J., Loh, J. M. I., & Preece, D. (2018). Should parents financially support their adult children? Normative views in Australia. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 39(2), 348–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-017-9558-z

Dunifon, R. E., Ziol-Guest, K. M., & Kopko, K. (2014). Grandparent coresidence and family well-being: Implications for research and policy. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 654(1), 110–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716214526530

Fuller-Thomson, E., Minkler, M., & Driver, D. (1997). A profile of grandparents raising grandchildren in the United States. The Gerontologist, 37(3), 406–411. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/37.3.406

Glaser, K., Stuchbury, R., Price, D., DiGessa, G., Ribe, E., & Tinker, A. (2018). Trends in the prevalence of grandparents living with grandchild(ren) in selected European countries and the United States. European Journal of Ageing, 15, 237–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-018-0474-3

Goodman, C., & Silverstein, M. (2002). Grandmothers raising grandchildren: Family structure and well-being in culturally diverse families. The Gerontologist, 42(5), 676–689. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/42.5.676

Harrington Meyer, M., & Herd, P. (2007). Market friendly or family friendly? The state and gender inequality in older age. Russell Sage Foundation. https://doi.org/10.7758/9781610443937

Harrington Meyer, M., & Kandic, A. (2017). Grandparenting in the United States. Innovation in Aging, 1(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igx023

Hayslip, B., Fruhauf, C. A., & Dolbin-MacNab, M. L. (2017). Grandparents raising grandchildren: What have we learned over the past decade? The Gerontologist, 57(6), 1196. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx106

Herlofson, K., & Hagestad, G. O. (2012). Transformations in the role of grandparents across welfare states. In S. Arber & V. Timonen (Eds.), Contemporary grandparenting: Changing family relationships in global contexts (1st ed., pp. 27–50). The Policy Press.

Johar, M., Maruyama, S., & Nakamura, S. (2015). Reciprocity in the formation of intergenerational coresidence. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 36(2), 192–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-013-9387-7

Luo, Y., LaPierre, T. A., Hughes, M. E., & Waite, L. J. (2012). Grandparents providing care to grandchildren: A population-based study of continuity and change. Journal of Family Issues, 33(9), 1143–1167.

Mutchler, J. E., & Baker, L. A. (2009). The implications of grandparent coresidence for economic hardship among children in mother-only families. Journal of Family Issues, 30(11), 1576–1597. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X09340527

Padgett, C. S., & Remle, R. C. (2016). Financial assistance patterns from midlife parents to adult children: A test of the cumulative advantage hypothesis. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 37(3), 435–449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-015-9461-4

Pilkauskas, N. V. (2012). Three generation family households: Differences by family structure at birth. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 74(5), 931–943. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.01008.x

Pilkauskas, N. V., & Cross, C. (2018). Beyond the nuclear family: Trends in children living in shared households. Demography, 55(6), 2283–2297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-018-0719-y

Pilkauskas, N. V., & Martinson, M. L. (2014). Three-generation family households in early childhood: Comparisons between the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. Demographic Research, 30, 1639–1652. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2014.30.60

Ruggles, S., Flood, S., Goeken, R., Grover, J., Meyer, E., Pacas, J., & Sobek, M. (2017). Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS USA: Version 7.0) . University of Minnesota. https://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V11.0

Sedgh, G., Finer, L. B., Bankole, A., Eilers, M. A., & Singh, S. (2015). Adolescent pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates across countries: Levels and recent trends. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(2), 223–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.007

Seltzer, J. A. (2019). Family change and changing family demography. Demography, 56(2), 405–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-019-00766-6

Silverstein, M., & Lee, Y. (2016). Race and ethnic differences in grandchild care and financial transfers with grandfamilies: An intersectional resource approach. In M. Harrington Meyer & Y. Abdul-Malak (Eds.), Grandparenting in the United States (1st ed., pp. 19–40). Routledge.

Silverstein, M., Lendon, J., & Giarrusso, R. (2012). Ethnic and cultural diversity in aging families: Implications for resource allocation and well-being across generations. In R. Blieszner & V. Hilkevitch Bedford (Eds.), Handbook of families and aging (2nd ed., pp. 212–307). ABC-CLIO, LLC.

Smith, P. M., Cawley, C., Williams, A., & Mustard, C. (2020). Male/female differences in the impact of caring for elderly relatives on labor market attachment and hours of work: 1997–2015. Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 75(3), 694–704. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbz026

Stokes, J. E., & Patterson, S. E. (2020). Intergenerational relationships, family caregiving policy, and COVID-19 in the United States. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 32(4–5), 416–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2020.1770031

United Nations. (2019). Living arrangements of older persons around the world (Population Facts No. 2019/2). Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/popfacts/PopFacts_2019-2.pdf

U.S. Census Bureau. (n.d.). American Community Survey (ACS). Why we ask: Grandparents as caregivers [Fact Sheet]. https://www.census.gov/acs/www/about/why-we-ask-each-question/grandparents/

U.S. Census Bureau. (n.d.). 2015: ACS 5-year estimates detail tables. Table B19049. CEDSCI. Retrieved April 19, 2021, from https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=median%20income%20age%202015&tid=ACSDT1Y2015.B19049

U.S. Census Bureau. (n.d.). Current population survey, March and annual social and economic supplements, 2014 and earlier. Retrieved December 18, 2021, from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/families/children.html

Wiemers, E. E. (2014). The effect of unemployment on household composition and doubling up. Demography, 51(6), 2155–2178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-014-0347-0

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Research Involving Human Participants and/or Animals

This research does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by either of the authors.

Informed Consent

This research does not contain any individually identified information.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mutchler, J.E., Velasco Roldán, N. Economic Resources Shaping Grandparent Responsibility Within Three-Generation Households. J Fam Econ Iss 44, 461–472 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-022-09842-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-022-09842-3