Abstract

Purpose

To examine current evidence of the known effects of advanced paternal age on sperm genetic and epigenetic changes and associated birth defects and diseases in offspring.

Methods

Review of published PubMed literature.

Results

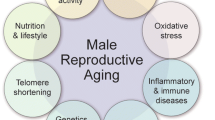

Advanced paternal age (> 40 years) is associated with accumulated damage to sperm DNA and mitotic and meiotic quality control mechanisms (mismatch repair) during spermatogenesis. This in turn causes well-delineated abnormalities in sperm chromosomes, both numerical and structural, and increased sperm DNA fragmentation (3%/year of age) and single gene mutations (relative risk, RR 10). An increase in related abnormalities in offspring has also been described, including miscarriage (RR 2) and fetal loss (RR 2). There is also a significant increase in rare, single gene disorders (RR 1.3 to 12) and congenital anomalies (RR 1.2) in offspring. Current research also suggests that autism, schizophrenia, and other forms of “psychiatric morbidity” are more likely in offspring (RR 1.5 to 5.7) with advanced paternal age. Genetic defects related to faulty sperm quality control leading to single gene mutations and epigenetic alterations in several genetic pathways have been implicated as root causes.

Conclusions

Advanced paternal age is associated with increased genetic and epigenetic risk to offspring. However, the precise age at which risk develops and the magnitude of the risk are poorly understood or may have gradual effects. Currently, there are no clinical screenings or diagnostic panels that target disorders associated with advanced paternal age. Concerned couples and care providers should pursue or recommend genetic counseling and prenatal testing regarding specific disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Khandwala YS, Zhang CA, Lu Y, Eisenberg ML. The age of fathers in the USA is rising: an analysis of 168 867 480 births from 1972 to 2015. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(10):2110–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dex267. 4096427 [pii]

Toriello HV, Meck JM. Statement on guidance for genetic counseling in advanced paternal age. Genet Med. 2008;10(6):457–60. https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e318176fabb.

Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine; Practice Committee of Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. Recommendations for gamete and embryo donation: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(1):47-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.09.037.

Bray I, Gunnell D, Davey SG. Advanced paternal age: how old is too old? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(10):851–3.

Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, Curtin SC, Matthews TJ. Births: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(1):1–65.

Kaler LW, Neaves WB. Attrition of the human Leydig cell population with advancing age. Anat Rec. 1978;192(4):513–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.1091920405.

Petersen PM, Pakkenberg B. Stereological quantitation of Leydig and Sertoli cellsin the testis from young and old men. Image Anal Stereol. 2000;9:215–8.

Harman SM, Metter EJ, Tobin JD, Pearson J, Blackman MR. Longitudinal effects of aging on serum total and free testosterone levels in healthy men. Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(2):724–31.

Johnson L, Petty CS, Neaves WB. Age-related variation in seminiferous tubules in men. A stereologic evaluation. J Androl. 1986;7(5):316–22.

Eskenazi B, Wyrobek AJ, Sloter E, Kidd SA, Moore L, Young S, et al. The association of age and semen quality in healthy men. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(2):447–54.

Ford WCL, North K, Taylor H, Farrow A, Hull MGR, Golding J, et al. Increasing paternal age is associated with delayed conception in a large population of fertile couples: evidence for declining fecundity in older men. Hum Reprod. 2000;15(8):1703–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/15.8.1703.

Luetjens CM, Rolf C, Gassner P, Werny JE, Nieschlag E. Sperm aneuploidy rates in younger and older men. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(7):1826–32.

Martin RH, Rademaker AW. The effect of age on the frequency of sperm chromosomal abnormalities in normal men. Am J Hum Genet. 1987;41(3):484–92.

McInnes B, Rademaker A, Martin R. Donor age and the frequency of disomy for chromosomes 1, 13, 21 and structural abnormalities in human spermatozoa using multicolour fluorescence in-situ hybridization. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(9):2489–94.

Lowe X, Eskenazi B, Nelson DO, Kidd S, Alme A, Wyrobek AJ. Frequency of XY sperm increases with age in fathers of boys with Klinefelter syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69(5):1046–54. https://doi.org/10.1086/323763.

Rubes J, Vozdova M, Oracova E, Perreault SD. Individual variation in the frequency of sperm aneuploidy in humans. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;111(3–4):229–36. https://doi.org/10.1159/000086893.

Wang J, Fan HC, Behr B, Quake SR. Genome-wide single-cell analysis of recombination activity and de novo mutation rates in human sperm. Cell. 2012;150(2):402–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.030.

Macklon NS, Geraedts JP, Fauser BC. Conception to ongoing pregnancy: the ‘black box’ of early pregnancy loss. Hum Reprod Update. 2002;8(4):333–43.

Bonduelle M, Van Assche E, Joris H, Keymolen K, Devroey P, Van Steirteghem A, et al. Prenatal testing in ICSI pregnancies: incidence of chromosomal anomalies in 1586 karyotypes and relation to sperm parameters. Hum ReprodHum Reprod. 2002;17(10):2600–14.

Crow JF. The origins, patterns and implications of human spontaneous mutation. Nat Rev Genet. 2000;1(1):40–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/35049558.

Moolgavkar SH, Knudson AG Jr. Mutation and cancer: a model for human carcinogenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1981;66(6):1037–52.

Conrad DF, Keebler JEM, DePristo MA, Lindsay SJ, Zhang YJ, Casals F, et al. Variation in genome-wide mutation rates within and between human families. Nat Genet. 2011;43(7):712–U137. https://doi.org/10.1038/Ng.862.

Kong A, Frigge ML, Masson G, Besenbacher S, Sulem P, Magnusson G, et al. Rate of de novo mutations and the importance of father’s age to disease risk. Nature. 2012;488(7412):471–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11396.

Rahbari R, Wuster A, Lindsay SJ, Hardwick RJ, Alexandrov LB, Turki SA, et al. Timing, rates and spectra of human germline mutation. Nat Genet. 2016;48(2):126–33. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3469.

Goriely A, McVean GA, Rojmyr M, Ingemarsson B, Wilkie AO. Evidence for selective advantage of pathogenic FGFR2 mutations in the male germ line. Science (New York, NY). 2003;301(5633):643–6. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1085710301/5633/643.

Maher GJ, Goriely A, Wilkie AO. Cellular evidence for selfish spermatogonial selection in aged human testes. Andrology. 2014;2(3):304–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2047-2927.2013.00175.x.

Makova KD, Li WH. Strong male-driven evolution of DNA sequences in humans and apes. Nature. 2002;416(6881):624–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/416624a.

Goriely A, Wilkie AO. Paternal age effect mutations and selfish spermatogonial selection: causes and consequences for human disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90(2):175–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.12.017.

Goriely A, McGrath JJ, Hultman CM, Wilkie AO, Malaspina D. “Selfish spermatogonial selection”: a novel mechanism for the association between advanced paternal age and neurodevelopmental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(6):599–608. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12101352.

Tiemann-Boege I, Navidi W, Grewal R, Cohn D, Eskenazi B, Wyrobek AJ, et al. The observed human sperm mutation frequency cannot explain the achondroplasia paternal age effect. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(23):14952–7. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.232568699.

Risch N, Reich EW, Wishnick MM, Mccarthy JG. Spontaneous mutation and parental age in humans. Am J Hum Genet. 1987;41(2):218–48.

Glaser RL, Broman KW, Schulman RL, Eskenazi B, Wyrobek AJ, Jabs EW. The paternal-age effect in Apert syndrome is due, in part, to the increased frequency of mutations in sperm. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73(4):939–47. https://doi.org/10.1086/378419.

Glaser RL, Jiang W, Boyadjiev SA, Tran AK, Zachary AA, Van Maldergem L, et al. Paternal origin of FGFR2 mutations in sporadic cases of Crouzon syndrome and Pfeiffer syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66(3):768–77. https://doi.org/10.1086/302831.

Hingorani M. Aniridia. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al., editors. GeneReviews. Seattle: University of Washington; 2003.

Olson JM, Breslow NE, Beckwith JB. Wilms’ tumour and parental age: a report from the National Wilms’ Tumour Study. Br J Cancer. 1993;67(4):813–8.

Dockerty JD, Draper G, Vincent T, Rowan SD, Bunch KJ. Case-control study of parental age, parity and socioeconomic level in relation to childhood cancers. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30(6):1428–37.

Yip BH, Pawitan Y, Czene K. Parental age and risk of childhood cancers: a population-based cohort study from Sweden. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(6):1495–503. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyl177.

Stonebraker JS, Bolton-Maggs PH, Soucie JM, Walker I, Brooker M. A study of variations in the reported haemophilia A prevalence around the world. Haemophilia. 2010;16(1):20–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2516.2009.02127.x.

Shore EM, Xu M, Feldman GJ, Fenstermacher DA, Cho TJ, Choi IH, et al. A recurrent mutation in the BMP type I receptor ACVR1 causes inherited and sporadic fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Nat Genet. 2006;38(5):525–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng1783.

Nyhan WL, O'Neill JP, Jinnah HA, Harris JC. Lesch-Nyhan syndrome. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al., editors. GeneReviews. Seattle: University of Washington; 2000.

Keane MG, Pyeritz RE. Medical management of Marfan syndrome. Circulation. 2008;117(21):2802–13. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.693523117/21/2802.

Carlson KM, Bracamontes J, Jackson CE, Clark R, Lacroix A, Wells SA Jr, et al. Parent-of-origin effects in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;55(6):1076–82.

Schuffenecker I, Ginet N, Goldgar D, Eng C, Chambe B, Boneu A, et al. Prevalence and parental origin of de novo RET mutations in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A and familial medullary thyroid carcinoma Le Groupe d’Etude des Tumeurs a Calcitonine. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60(1):233–7.

Bunin GR, Needle M, Riccardi VM. Paternal age and sporadic neurofibromatosis 1: a case-control study and consideration of the methodologic issues. Genet Epidemiol. 1997;14(5):507–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2272(1997)14:5<507::AID-GEPI5>3.0.CO;2-Y.

Loddenkemper T, Grote K, Evers S, Oelerich M, Stogbauer F. Neurological manifestations of the oculodentodigital dysplasia syndrome. J Neurol. 2002;249(5):584–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004150200068.

Orioli IM, Castilla EE, Scarano G, Mastroiacovo P. Effect of paternal age in achondroplasia, thanatophoric dysplasia, and osteogenesis imperfecta. Am J Med Genet. 1995;59(2):209–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.1320590218.

Carothers AD, McAllion SJ, Paterson CR. Risk of dominant mutation in older fathers: evidence from osteogenesis imperfecta. J Med Genet. 1986;23(3):227–30.

Torres VE, Harris PC. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: the last 3 years. Kidney Int. 2009;76(2):149–68. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2009.128.

Rivera B, Gonzalez S, Sanchez-Tome E, Blanco I, Mercadillo F, Leton R, et al. Clinical and genetic characterization of classical forms of familial adenomatous polyposis: a Spanish population study. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(4):903–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdq465.

Eriksson M, Brown WT, Gordon LB, Glynn MW, Singer J, Scott L, et al. Recurrent de novo point mutations in lamin A cause Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Nature. 2003;423(6937):293–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01629.

Gordon LB, Brown WT, Collins FS. Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome. In Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Stephens K, Amemiya A, editors. GeneReviews. [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2018. 2003 Dec 12 [updated 2015 Jan 8].

Splendore A, Jabs EW, Felix TM, Passos-Bueno MR. Parental origin of mutations in sporadic cases of Treacher Collins syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2003;11(9):718–22. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201029.

Northrup H, Koenig MK, Au KS. Tuberous sclerosis complex. Seattle: University of Washington; 2003.

Sampson JR, Scahill SJ, Stephenson JB, Mann L, Connor JM. Genetic aspects of tuberous sclerosis in the west of Scotland. J Med Genet. 1989;26(1):28–31.

Tamayo ML, Gelvez N, Rodriguez M, Florez S, Varon C, Medina D, et al. Screening program for Waardenburg syndrome in Colombia: clinical definition and phenotypic variability. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A(8):1026–31.

Milunski JM. Waardenburg syndrome type I. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al., editors. GeneReviews. Seattle: University of Washington; 2001.

Yang Q, Wen SW, Leader A, Chen XK, Lipson J, Walker M. Paternal age and birth defects: how strong is the association? Hum Reprod. 2007;22(3):696–701. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/del453.

Lian ZH, Zack MM, Erickson JD. Paternal age and the occurrence of birth defects. Am J Hum Genet. 1986;39(5):648–60.

Olshan AF, Schnitzer PG, Baird PA. Paternal age and the risk of congenital heart defects. Teratology. 1994;50(1):80–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/tera.1420500111.

Green RF, Devine O, Crider KS, Olney RS, Archer N, Olshan AF, et al. Association of paternal age and risk for major congenital anomalies from the National Birth Defects Prevention Study, 1997 to 2004. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20(3):241–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.10.009.

Montgomery SM, Lambe M, Olsson T, Ekbom A. Parental age, family size, and risk of multiple sclerosis. Epidemiology. 2004;15(6):717–23.

Murray L, McCarron P, Bailie K, Middleton R, Davey Smith G, Dempsey S, et al. Association of early life factors and acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in childhood: historical cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2002;86(3):356–61. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6600012.

Zhang Y, Kreger BE, Dorgan JF, Cupples LA, Myers RH, Splansky GL, et al. Parental age at child’s birth and son’s risk of prostate cancer. Framingham Study Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150(11):1208–12.

Choi JY, Lee KM, Park SK, Noh DY, Ahn SH, Yoo KY, et al. Association of paternal age at birth and the risk of breast cancer in offspring: a case control study. BMC Cancer. 2005;5:143. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-5-143.

Slama R, Bouyer J, Windham G, Fenster L, Werwatz A, Swan SH. Influence of paternal age on the risk of spontaneous abortion. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(9):816–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwi097.

Reichman NE, Teitler JO. Paternal age as a risk factor for low birthweight. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(5):862–6. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.066324.

Harlap S, Paltiel O, Deutsch L, Knaanie A, Masalha S, Tiram E, et al. Paternal age and preeclampsia. Epidemiology. 2002;13(6):660–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.EDE.0000031708.99480.70.

Cardwell CR, Carson DJ, Patterson CC. Parental age at delivery, birth order, birth weight and gestational age are associated with the risk of childhood type 1 diabetes: a UK regional retrospective cohort study. Diabet Med. 2005;22(2):200–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01369.x.

Vestergaard M, Mork A, Madsen KM, Olsen J. Paternal age and epilepsy in the offspring. Eur J Epidemiol. 2005;20(12):1003–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-005-4250-2.

Reichenberg A, Gross R, Weiser M, Bresnahan M, Silverman J, Harlap S, et al. Advancing paternal age and autism. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2006;63(9):1026–32. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.63.9.1026.

de Kluiver H, Buizer-Voskamp JE, Dolan CV, Boomsma DI. Paternal age and psychiatric disorders: a review. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2017;174(3):202–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.b.32508.

Rasmussen F. Paternal age, size at birth, and size in young adulthood—risk factors for schizophrenia. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;155:S65–S9. https://doi.org/10.1530/Eje.1.02264.

Croen LA, Najjar DV, Fireman B, Grether JK. Maternal and paternal age and risk of autism spectrum disorders. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(4):334–40. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.161.4.334.

Saha S, Barnett AG, Foldi C, Burne TH, Eyles DW, Buka SL, et al. Advanced paternal age is associated with impaired neurocognitive outcomes during infancy and childhood. PLoS Med. 2009;6(3):e40. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000040.

Jayasekara R, Street J. Parental age and parity in dyslexic boys. J Biosoc Sci. 1978;10(3):255–61.

Frans EM, Sandin S, Reichenberg A, Lichtenstein P, Langstrom N, Hultman CM. Advancing paternal age and bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(9):1034–40. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.65.9.103465/9/1034.

Bertram L, Busch R, Spiegl M, Lautenschlager NT, Muller U, Kurz A. Paternal age is a risk factor for Alzheimer disease in the absence of a major gene. Neurogenetics. 1998;1(4):277–80.

Jenkins TG, Aston KI, Pflueger C, Cairns BR, Carrell DT. Age-associated sperm DNA methylation alterations: possible implications in offspring disease susceptibility. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(7):e1004458. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004458.

Milekic MH, Xin Y, O'Donnell A, Kumar KK, Bradley-Moore M, Malaspina D, et al. Age-related sperm DNA methylation changes are transmitted to offspring and associated with abnormal behavior and dysregulated gene expression. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20(8):995–1001. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2014.84.

D'Onofrio BM, Rickert ME, Frans E, Kuja-Halkola R, Almqvist C, Sjolander A, et al. Paternal age at childbearing and offspring psychiatric and academic morbidity. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(4):432–8.

Day K, Waite LL, Thalacker-Mercer A, West A, Bamman MM, Brooks JD, et al. Differential DNA methylation with age displays both common and dynamic features across human tissues that are influenced by CpG landscape. Genome Biol. 2013;14(9):R102. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2013-14-9-r102.

Bungum M, Humaidan P, Spano M, Jepson K, Bungum L, Giwercman A. The predictive value of sperm chromatin structure assay (SCSA) parameters for the outcome of intrauterine insemination, IVF and ICSI. Hum Reprod. 2004;19(6):1401–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deh280.

Wyrobek AJ, Eskenazi B, Young S, Arnheim N, Tiemann-Boege I, Jabs EW, et al. Advancing age has differential effects on DNA damage, chromatin integrity, gene mutations, and aneuploidies in sperm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(25):9601–6.

Marchetti F, Wyrobek AJ. Mechanisms and consequences of paternally-transmitted chromosomal abnormalities. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2005;75(2):112–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdrc.20040.

Nybo Andersen AM, Hansen KD, Andersen PK, Davey SG. Advanced paternal age and risk of fetal death: a cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(12):1214–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/.

Ramasamy R, Chiba K, Butler P, Lamb DJ. Male biological clock: a critical analysis of advanced paternal age. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(6):1402–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.03.011.

Kuhnert B, Nieschlag E. Reproductive functions of the ageing male. Hum Reprod Update. 2004;10(4):327–39. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmh030.

Lambert SM, Masson P, Fisch H. The male biological clock. World J Urol. 2006;24(6):611–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-006-0130-y.

Sartorius GA, Nieschlag E. Paternal age and reproduction. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16(1):65–79. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmp027.

Malaspina D, Harlap S, Fennig S, Heiman D, Nahon D, Feldman D, et al. Advancing paternal age and the risk of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(4):361–7.

Brown AS, Schaefer CA, Wyatt RJ, Begg MD, Goetz R, Bresnahan MA, et al. Paternal age and risk of schizophrenia in adult offspring. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1528–33.

Forster P, Hohoff C, Dunkelmann B, Schurenkamp M, Pfeiffer H, Neuhuber F, et al. Elevated germline mutation rate in teenage fathers. Proc Biol Sci. 2015;282(1803):20142898. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.2898.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yatsenko, A.N., Turek, P.J. Reproductive genetics and the aging male. J Assist Reprod Genet 35, 933–941 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-018-1148-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-018-1148-y