Abstract

Smoking is frequently presented as being particularly problematic when the smoker is a pregnant woman because of the potential harm to the future child. This premise is used to justify targeting pregnant women with a unique approach to smoking cessation including policies such as the routine testing of all pregnant women for carbon monoxide at every antenatal appointment. This paper examines the evidence that such policies are justified by the aim of harm prevention and argues that targeting pregnant women in this way is likely to do more harm than good. Routine carbon monoxide testing is particularly problematic as it sends a message to pregnant women that they cannot be trusted either to truthfully answer questions as to whether or not they smoke, or to make decisions in the best interests of themselves and their future children in the way that non-pregnant individuals are. Further, if the aim is to reduce rates of prenatal harm, the evidence suggests that adopting a supportive and empowering approach to prenatal care is the most effective way to achieve this, something that the current policies aimed at pregnant women are in conflict with.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is normally assumed that pregnant women not only want their future children to be born as healthy as possible, but that they are also under a moral obligation to protect those future children during their fetal stage if they are intending to bring them to birth [12, 49]. This assumption underlies public health policies advocating interventions in pregnancy including those that aim to persuade women to limit their alcohol consumption, control their weight and stop smoking [37, 38, 59]. This paper focuses on a particular public health intervention, routinely testing pregnant women for carbon monoxide to encourage smoking cessation, and asks whether such measures are justified.

While there has been a great deal of discussion around what moral obligations pregnant women might have to their fetuses and the children their fetuses might become, and how this should affect law and policy in this area [6, 12, 13, 39, 45, 48, 49, 54, 56], this paper seeks to explore a different but equally important question. It seeks to avoid the intractable nature of the debate concerning what moral obligations pregnant women might have, by starting from the assumption that a convincing case has been made that pregnant women have a moral obligation to take reasonable steps to avoid causing their future children harm. By making this assumption, I am then able to focus on the fundamental question of whether the evidence suggests that public health measures such as routine carbon monoxide testing in pregnancy are likely to achieve their aim of preventing harm to future children. This question has received little attention despite its significance for policy making, as well as the ethical and legal issues it raises. Without strong evidence of harm prevention, such interventions and their implications for the lives of pregnant women cannot be justified.

Smoking Cessation Interventions in Pregnancy

Non-pregnant smokers are frequently offered support to quit, including nicotine replacement therapies, support groups and counseling [41].Footnote 1 However, in England it is only pregnant women who, irrespective of whether they say they are smokers or not, are now to be routinely screened and monitored using carbon monoxide tests at all prenatal care appointments [16].Footnote 2 As the majority of routine face-to-face antenatal care in the UK is delivered by midwives, the task of performing the carbon monoxide tests falls to them, although some auxiliary staff have been involved where resources allow [35]. The implementation of this policy is therefore significant for the relationship between pregnant women and midwives. The policy was trialled in the North East of England in the Babyclear programme [22] and following the 2010 NICE Guidelines, ‘Smoking: stopping in pregnancy and after childbirth’ (the NICE Guidelines) [38] has been adopted by a number of NHS Trusts across England, Scotland and Wales.Footnote 3 The test involves the midwife holding a doll connected to a model placenta, informing the pregnant woman that when you have a cigarette “…it is as if someone gets hold of your baby’s cord and squeezes it really really hard and you can see that if that was held really tightly and squeezed really tightly, that stops the oxygen getting to your baby.” [23] The woman is told that this will mean it will be a smaller, weaker baby, likely to need special care and she is likely to need a caesarean section [23]. The midwife then states that if it is alright with the woman she would like to do the test [23]. It is possible for a pregnant woman to refuse the test, but the fact that it is to be offered routinely at all antenatal appointments and given the emotive language used; presenting it as a test to see if someone is taking hold of the umbilical cord and squeezing it tightly, it seems inevitable that pregnant women will feel pressurised to take it. The pregnant woman then gives a breath sample connected to a computer screen displaying a picture of a fetus which changes from green to amber, to flashing red with an alarm sounding depending on the level of carbon monoxide in the woman’s breath. If a high level of carbon monoxide is detected the woman is informed that her baby “…is in danger” and is struggling [23].

This goes beyond the support to quit offered to non-pregnant smokers, with a lack of trust inherent in testing all pregnant women for carbon monoxide levels regardless of whether they say they smoke or not. It could be argued that the test detects the presence of carbon monoxide rather than whether the woman smokes, as some level of carbon monoxide could be present from other sources. However, the purpose of the test is to discover if a pregnant woman smokes or not, as stated in the NICE Guidelines [38]. If a carbon monoxide test is needed to determine whether a pregnant woman smokes rather than relying on whether she says she does, this indicates that a pregnant woman cannot be trusted to answer this question truthfully.

It could be argued that targeting pregnant smokers is justified on the basis of preventing harm to the pregnant women themselves, utilising the window of opportunity that the close contact with health services provides [7, 10]. However, this would only justify such measures if a similar approach was taken to other windows of opportunity, including the partners of pregnant women, parents of existing children and patients receiving treatment for other conditions. While these individuals may be offered smoking cessation services, they are not being routinely tested to determine if they smoke or not. Further, if this were the justification for targeting pregnant smokers the emotional presentation connected to the future child’s wellbeing would not be justified. It is clear that pregnant women are being treated differently because of the potential health risks to their future children.

Therefore, the question is, is singling pregnant women out for such pressurised interventions justified in order to prevent harm to future children?Footnote 4

This paper suggests that for this to be the case four things would need to be established:

-

1.

that smoking during pregnancy causes significant prenatal harm to future children;

-

2.

that carbon monoxide testing reduces rates of smoking during pregnancy;

-

3.

that such interventions do not cause more harm to future children than they prevent; and

-

4.

that there is no alternative, less problematic way to reduce prenatal harm.

It argues that these things cannot be established and therefore carbon monoxide testing in pregnancy cannot be justified on the grounds of preventing harm to future children.

1. Does Smoking During Pregnancy Cause Significant Prenatal Harm to Future Children?

This condition must be satisfied if the potential harm to future children is to justify the uniquely pressurised approach to smoking cessation during pregnancy. After all, if smoking during pregnancy is no more harmful than at other times, there would be no reason to single out pregnant women for these measures.

Although there is a significant amount of evidence linking smoking during pregnancy to low birthweight, stillbirth and premature delivery, this is not the only factor linked to such harms [34, 43] and the issue of causation beyond correlation remains unclear.Footnote 5 Significantly, the majority of studies linking smoking during pregnancy to these harms have not looked in depth at the role of social factors such as education and poverty. The evidence suggests that such harms could be reduced in a number of ways including reducing inequality [43], improving nutrition [2], increasing education [57], encouraging men not to smoke [9, 19, 47], or encouraging pregnant women not to smoke [17]. Therefore, the choice to view these harms as primarily a problem of individual behaviour during pregnancy requires justification.

The assertions about the health risks of smoking during pregnancy contained in the NICE Guidelines are based on a 1992 report of the Royal College of Physicians [58] and a claim in The Department of Health’s ‘Review of the health inequalities infant mortality PSA target’ (the DOH Review) [20], that smoking during pregnancy increases the risk of infant mortality by an estimated 40% [38]. The DOH Review states that babies born to women who smoke are more likely to be born prematurely, are twice as likely to have a low birthweight and are up to 3 times more likely to die from sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) [20]. This is based on research which states that the causal mechanisms by which smoking and other risk factors influence the likelihood of preterm birth remain unknown and highlights the fact that many factors are associated with an increased risk of preterm birth [25]. Further, it states that infections are implicated in at least 40% of preterm births and as much as 70% for births prior to 32 weeks gestation [25]. The claim in the DOH Review that the likelihood of infant mortality is increased by about 40% is a finding of correlation as a result of a statistical analysis [46]. Similarly, the 1992 report of the Royal College of Physicians establishes a correlation between smoking during pregnancy and outcomes such as low birthweight but not a direct causal link [58]. One Swedish study has attempted to isolate the effects of smoking during pregnancy from other maternal characteristics by comparing the birthweights of siblings born to mothers who smoked in one pregnancy but not another [31]. This study found that maternal smoking during pregnancy did reduce birthweight but not by as much as was predicted by conventional analysis. Further, as its authors acknowledge this study still does not establish a causal link as other factors linked to the change in the mother’s smoking behaviour such as stress, relationship breakdown and nutrition have not been accounted for [31].

Another study which sought to look beyond correlation is that conducted by Emma Tominey in 2007 which analysed data on the lives of 6500 children and their mothers, considering in detail the lifestyles of the mothers [57]. By controlling for variables including grandparent smoking habits during adolescence, maternal birthweight and paternal smoking habits, it was able to establish that the harm often attributed to smoking during pregnancy varies according to the education of the mother, and unobservable traits of the mother such as nutrition and knowledge of healthy behaviour. The study concluded that:

…around one-third of the harm from smoking is explained by unobservable traits of the mother. Smoking tends to reduce birthweight by 1.7% but has no significant effect on the probability of having a low birthweight child, pre-term gestation or weeks of gestation [57].

A further claim is made in the NICE Guidelines that “exposure to smoke in the womb is associated with psychological problems in childhood such as attention and hyperactivity problems and disruptive and negative behaviour.” [38]Footnote 6 However, the link between prenatal smoking and childhood behavioural problems has been questioned in a study which concluded that once compounding factors such as maternal antisocial behaviour were taken into account, prenatal smoking was no longer associated with antisocial behaviour in children [11].

Establishing a causal link beyond correlation between smoking during pregnancy and harms such as low birthweight is problematic given the difficulties in isolating smoking from other potentially causal factors. However, a strong indication of a causal link would be if reducing smoking rates during pregnancy led to reduced rates of prenatal harm.

Does Reducing Smoking Rates During Pregnancy Reduce Prenatal Harm?

Although most reviews of the effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions in pregnancy focus on their ability to reduce smoking rates rather than their ability to reduce harm to future children, there is evidence that smoking cessation interventions can reduce low birthweight and preterm birth [4]. However, the link between reducing smoking rates and prenatal harm is not a straightforward one.

This is illustrated by a study which considered the impact of declining rates of maternal smoking during pregnancy on the number of low birthweight babies in Massachusetts from 1989 to 2004 [32]. During this period there was a significant yearly decline of at least 6% in maternal smoking prevalence during pregnancy. However, over the same period a significant increase of up to 1% in the prevalence of low birthweight babies occurred. The report concluded that factors other than maternal smoking had reversed the potential gains attributable to reductions in maternal smoking. However, it seems equally possible that the link between smoking and low birthweight is one of correlation rather than causation and other factors such as poverty and low education which are aligned with smoking rates could be more significant causes of low birthweight. Similarly, it could be that at least some of the positive effects of smoking cessation interventions could be explained by side effects of the specific delivery of the interventions, such as increased contact with healthcare professionals or other simultaneous interventions regarding nutrition and lifestyle.

Particularly significant is the conclusion of Emma Tominey’s study that only up to 13% of the babies classified as low birthweight, born to mothers who smoked during pregnancy could have been classified as being of healthy weight had their mothers not smoked [57]. Such a low prevention rate seems insufficient to justify presenting such prenatal harm as solely a problem of the individual behaviour of pregnant women. After all, in 87% of cases the prenatal harm associated with maternal smoking (low birthweight), would have occurred even if the mother did not smoke during pregnancy. Further, the impact of smoking is much greater for mothers of low education, even controlling for the quantity of cigarettes they smoke, clearly indicating that factors other than the woman’s smoking are at play [57]. Therefore, while reducing smoking rates during pregnancy might lead to some reduction in prenatal harm, it is not clear that a more significant reduction could not be achieved by focussing on a different factor.

Assuming that condition 1 is fulfilled and reducing smoking rates during pregnancy has some beneficial impact on the rates of prenatal harm, for the policy of routine carbon monoxide testing in pregnancy to be justified, it must still be established that this specific smoking cessation measure is likely to be effective.

2. Does Routine Carbon Monoxide Testing Reduce Rates of Smoking During Pregnancy?

The NICE Guidelines, recommend that a carbon monoxide test be used to identify pregnant women who smoke as “some women find it difficult to say that they smoke because the pressure not to smoke during pregnancy is so intense.” [38] Targeting the behaviour of pregnant women with carbon monoxide testing is unlikely to alleviate this pressure, particularly as pregnant smokers might find it difficult to admit they smoke because they fear they will be judged and emotionally blamed for something they feel they have little control over. If pregnant women are treated with distrust by their midwives and emotional, coercive language is used, they are unlikely to be encouraged to engage with smoking cessation services and prenatal care more generally. An alternative would be to make pregnant women feel respected and trusted and support them in what they feel is best for them and their future children. Indeed, the NICE Guidelines state that because some pregnant women find it difficult to say that they smoke it is important to communicate in a sensitive, client-centred manner [38]. It is difficult to see how the lack of trust displayed by the policy to routinely test pregnant women for carbon monoxide fulfils this requirement.

Further, it is equally plausible that a non-pregnant smoker might not admit to smoking in order to avoid feelings of judgment and pressure to quit, yet it is only pregnant women who are to be routinely screened for carbon monoxide levels. This policy sends out a message to pregnant women that they cannot be trusted either to truthfully answer questions about whether or not they smoke, or to make the right decisions in the interests of themselves and their future children in the way non-pregnant individuals can. Not only does this raise ethical concerns because it involves unequal respect for the autonomy of pregnant women compared to individuals who are not pregnant, but it is also likely to have a negative impact on the health outcomes for pregnant women and their future children as research suggests that respecting the autonomy of pregnant women is linked to better outcomes for mother and babies [3, 50].

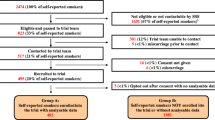

One problem with evaluating the effectiveness of routine carbon monoxide testing is that instead of asking whether the policy reduces rates of prenatal harm, the policy is frequently assessed on the percentage of pregnant smokers that it identifies. This not only fails to take account of the possibility that smokers identified in this way might be less likely to engage with smoking cessation measures and go on to quit, but it also ignores the possibility that such policies might lead to increased prenatal harm in other ways. For example, one study trialled the use of routine carbon monoxide testing as part of a smoking cessation programme targeting pregnant women across three maternity units serving Glasgow in Scotland [35]. While it suggested that utilising carbon monoxide testing alongside self-reporting could increase identification of pregnant smokers from 80 to 94%, it found that booking midwives found it difficult to approach all pregnant women to talk about smoking and this was not made easier by the requirement that all pregnant women should be tested for carbon monoxide at the initial booking appointment.Footnote 7 This indicates that a policy of routine carbon monoxide testing might actually hinder midwives from raising smoking cessation with pregnant women and even decrease rates of pregnant women who successfully quit smoking. The CATCH programme also operated in Glasgow, employing a similar approach to smoking cessation using motivational interviews to engage pregnant smokers during telephone contact and withdrawal orientated therapy including nicotine replacement therapy [14]. However, it differed from the ‘breathe’ programme in that it delivered care in a home setting rather than a clinic; it operated a holistic approach, helping women to solve more pressing problems such as housing, before smoking; the referral model was opt-in rather than opt-out; and smokers were not initially identified by routine carbon monoxide testing. While no data was collected as to whether CATCH identified fewer smokers than ‘breathe’, the data suggests that CATCH achieved a better quit rate than ‘breathe’.

While pregnant smokers need to be identified to be supported to quit, the goal of reducing prenatal harm to future children should not be reduced to identifying pregnant smokers. No information was collected as part of this study on the rates of low birth weight or premature delivery as a result of these interventions. Further, it does not support the claim that routine carbon monoxide testing itself leads to better rates of smoking cessation. It is possible, if not probable, that those smokers who would only be identified as smokers by carbon monoxide testing rather than self-reporting, would be less likely to be motivated to quit and engage with smoking cessation measures. Treating them with distrust is unlikely to change this. Therefore, while the evidence indicates that carbon monoxide testing could increase the number of pregnant smokers identified, it does not allow the conclusion to be made that a policy of routine carbon monoxide testing of pregnant women would reduce rates of smoking during pregnancy and so condition 2 is not satisfied.

However, even if conditions 1 and 2 were met, the policy of singling out pregnant women for routine carbon monoxide testing would only be justified on the basis that it reduces prenatal harm to future children, if it could be shown that such measures do not cause more harm to future children than they prevent.

3. Do Such Interventions Cause More Harm to Future Children than They Prevent?

It could be argued that even if smoking during pregnancy is not as harmful as other factors such as poverty, a lack of education, genetic factors, poor nutrition, or a lack of good quality prenatal care, smoking during pregnancy is harmful to some extent and therefore it is still a good thing to reduce smoking rates among pregnant women. It is likely that it would be of some benefit to future children and to others, including the women themselves, if women did not smoke during pregnancy.Footnote 8 It is also possible that some pregnant smokers may quit smoking having been identified as smokers through carbon monoxide testing and therefore, a policy of routine testing might prevent some prenatal harm. The problem with justifying the policy on the basis that it could prevent some prenatal harm is that it assumes that targeting the behaviour of pregnant women in this way is not in itself, harmful to future children.

There are three ways in which the policy to routinely test pregnant women for carbon monoxide has the potential to cause harm to future children. Firstly, by focussing on the behaviour of pregnant women other more significant causes of prenatal harm such as poverty and poor prenatal care are obscured and overlooked [28]. This can occur on both a public health level and an individual level. On a public health level, if responsibility for these harms lies with the pregnant women themselves then the calls for the state to address social factors such as poverty and education are weakened, resulting in a missed opportunity to improve the welfare of future children to a much greater extent. On an individual level, policies which require health professionals to focus on certain factors such as smoking cessation to the extent of testing every pregnant woman for carbon monoxide at every antenatal appointment has the potential to interfere with the professional’s own assessment of the individual patient’s health needs, requiring them to use the limited contact time they have with patients pursuing public health priorities rather than the health priorities of the individuals. As studies into the ethical issues raised by health visitors delivering public health measures have shown, this can lead to health professionals feeling that they are wasting time, inadequately addressing more pressing needs of the individual and eroding their ability to form relationships of trust with their patients [26].

Similarly, as Kukla has argued, healthcare policies which focus on maternal behaviour at signal moments surrounding pregnancy and birth fail to take account of the extended narrative of motherhood (and indeed parenthood) and so miss the opportunity to genuinely improve the welfare of future children by supporting their parents to be “good parents” in the long term. This reductive view of motherhood focuses on individual responsibility rather than fostering the conditions which enable individuals to make good choices in the longer narrative of motherhood [33]. The welfare of future children depends on a wide range of factors and focusing narrowly on individual behaviour such as smoking during pregnancy oversimplifies the issue and prevents what are likely to be more significant factors from being addressed by obscuring their importance and restricting healthcare professionals’ ability to deliver individualised patient-centred care.

Secondly, the feeling of judgment and blame connected with such individualisation, could act as a deterrent to engaging with prenatal care. This is supported by recent studies in the context of support for self-management of long-term health conditions which have found that focusing on behavioural deficits and emphasising biomedical and clinical epidemiological research reinforces the position of healthcare professionals as experts and this hierarchical view of the patient-professional relationship prevents patients from acting as effective partners in their own care [21]. Thus, presenting the problem of prenatal harm as one of pregnant women choosing not to conform to what medical science tells them is best for their babies, is likely to disempower pregnant women from taking an active role in their care. Further, as has been noted in connection with personal responsibility in other forms of healthcare there is likely to be a significant reduction in trust between health professionals and patients if judgment and blame is perceived [24]. This seems a particular risk in routine screening for carbon monoxide for all mothers regardless of whether they say they smoke and would like help to stop or not. This impact on the relationship between pregnant women and healthcare professionals means that not only are the most significant causes of prenatal harm obscured by the individualisation of the problem, but they are actually exacerbated by it. The most vulnerable women who would benefit most from good quality prenatal care may disengage with that care due to fear of judgment and blame and their future children are therefore more likely to suffer prenatal harm.

One study looking at the experiences of midwives administering the carbon monoxide test found that, despite initial concerns, midwives have not found carbon monoxide testing to be problematic [42]. The midwives interviewed reported that although they had initially been concerned about the lack of research and evidence base for using carbon monoxide testing as well as concerns about the potential for such testing to negatively impact on their relationships with their patients if the test was used as a ‘lie detector’, the test had quickly become an accepted part of routine care. While these findings are initially encouraging, as its authors recognise, this study is limited in a number of ways. Firstly, at the time of the study it was difficult to find midwives who were routinely using the test at the initial booking appointment, as currently advised. This prevents it being an accurate assessment of the impact of the policy to routinely test all women at all antenatal appointments. Secondly, most of the participants were recruited from an area with a low-smoking prevalence. It seems likely that the test would be most problematic in areas of high smoking prevalence as it is smokers who will potentially feel judged and blamed for their behaviour rather than non-smokers. Finally, the study only considered whether the midwives had found the use of carbon monoxide screening problematic and did not speak to the pregnant women regarding their experiences. Even if midwives did not feel the test significantly altered their interactions with pregnant women, the pregnant women might have experienced the test differently.

Thirdly, it is likely that outcomes for future children are improved when the autonomy of their mothers is respected during pregnancy [3, 50]. In this context, respecting autonomy requires that women are encouraged to pay an active role in their own care and that they are trusted to be the ultimate decision makers, with health professionals supporting their decisions. In other aspects of healthcare this patient engagement has been shown to produce better outcomes for individual patients [18]. Due to the interconnected nature of the interests of a woman and her future child, something that is in the interests of pregnant women will most likely be in the interests of future children. If, as the evidence suggests, outcomes for patients are improved when they take an active role in their own care and are empowered to do so by healthcare professionals, it seems logical that outcomes for future children will improve when the individuals most connected to and invested in their wellbeing are empowered in this way. This is supported by studies in Bangladesh and Nepal which indicate that children born to mothers who have more power to make decisions in their everyday lives and regarding their medical care, have better outcomes than those born to women whose autonomy is less respected [3, 50]. This is to be expected once the pregnant woman is recognised as a protector rather than a threat to the future child.

Pressurising pregnant women to stop smoking using routine carbon monoxide testing and emotional coercion as opposed to presenting information and offering support if desired, assumes that pregnant women are either unable or unwilling to make the best choices for themselves and their future children in the way that other individuals are. There is no evidence that this is the case and policies based on this assumption in turn, contribute to the undermining of the autonomy of pregnant women. As argued by Entwistle et al in relation to support for self-management of long term health conditions, negative judgmental attitudes towards patients, including using tests to suggest that the patients’ claims about their behaviour are false, can cause patients to feel anxious, hopeless and disrespected which can be understood as undermining their autonomy [21]. Even when looking narrowly at the issue of smoking, research has shown that the more confident and capable a woman considered herself to be at the transition to motherhood, the less likely she is to relapse into smoking [5]. Therefore, there is a very real possibility that routine carbon monoxide testing could cause pregnant smokers to feel undermined and so decrease the chances of them quitting in the long term.

The narrow focus on reducing harms to future children such as low birthweight and pre-term delivery has meant that harms to autonomy and the general wellbeing of pregnant woman and future child have not been taken into account. It is not part of the purpose of policies such as routine carbon monoxide testing to enhance or protect the autonomy of pregnant women and thus this potential negative impact on the welfare of future children is not part of the cost-benefit analysis undertaken. Therefore, such policies are potentially harmful to future children as well as to the women who bear them.

It could be argued that placing extra pressure to quit smoking on pregnant women is justified because it is a case of one individual (the pregnant woman) harming another individual (the future child) rather than an individual harming themselves by smoking, or that there is something specific about it being a future child that is harmed and the pregnant woman’s relationship to it, that makes smoking while pregnant more problematic than smoking at other times. While it seems likely that a pregnant woman who chooses to bring a child to birth has a moral duty to take the interests of the future child into account it is difficult to see why this should be any greater than the duty owed by a parent of an existing child. [12] Given the risks of passive smoking, if it is not necessary to screen parents of existing children for carbon monoxide, it is difficult to see why this would justify targeting pregnant women in this way. In any event, if the policy was to be justified on the grounds that it prevented an especially significant type of harm, i.e. harm to a future child by its mother during pregnancy, it would still be necessary to show that the policy did indeed prevent such harm.

Arguments could also be made against such policies on the basis that they are harmful to pregnant women. However, such arguments are problematic as they involve balancing harms and benefits to one individual (the future child) with those caused to another individual (the pregnant woman). It could be argued that preventing harm to one at the cost of another is justified either because one is more deserving of protection or because of some sense of culpability on the part of the other. In this case the argument would be that it is acceptable for pregnant women to be harmed by measures taken to protect future children because pregnant women are not as vulnerable as future children, and they are the ones creating the risk. However, there are several problems with this argument. First, policies such as carbon monoxide testing all pregnant women at every antenatal appointment have the potential to harm pregnant smokers and non-smokers and even women in general. The message of distrust is communicated to all women. Second, if such policies are to be based on the culpability of pregnant smokers, the argument to support this has not been made. There are clear issues surrounding the degree of choice exercised by women who do not give up smoking during pregnancy due to the addictive nature of smoking and it is not clear why a pregnant smoker should be considered more culpable for any resulting harm than a parent of an existing child or any other smoker. Finally, there is an inherent problem with balancing potential harms to pregnant women with those to future children because they are not two separate individuals; their welfare is uniquely interconnected because of their physical and emotional connection. Harming pregnant women will also harm future children. This illustrates the problematic nature of the traditional maternal-fetal conflict model which presents the interests of the pregnant woman as conflicting with those of the future child and therefore, the pregnant woman as a threat to her future child rather than the person who is most invested in its welfare. In any event, any argument supporting smoking cessation measures in pregnancy to address prenatal harm to future children requires evidence that such measures will reduce harm to future children before this can be considered alongside any potential harms to pregnant women.

It is clear that even if smoking during pregnancy causes significant prenatal harm and routine carbon monoxide testing has some positive effect on smoking rates during pregnancy fulfilling conditions 1 and 2, it is extremely unlikely that condition 3 will be met. Not only are there other causal factors which could be addressed to greater effect, but pressurising pregnant women to quit smoking in this way is harmful in itself. The policy is likely to obscure more significant causes of prenatal harm, have a negative effect on engagement with antenatal care and reduce rather than strengthen women’s autonomy and their role in their own care.

4. Is There an Alternative, Less Problematic Way to Reduce Prenatal Harm?

An alternative strategy for improving outcomes for future children is to move away from presenting the needs of a developing fetus as being in conflict with those of the pregnant woman. Once we accept that in the vast majority of cases, a pregnant woman wants to do what is best for her future child and will do whatever she can to protect that future child, it becomes clear that far from smoking during pregnancy warranting a more pressurised approach, if anything, given her additional motivation, less pressure is required and we should look instead to providing the woman with support.

It seems likely from the evidence discussed above that there would be some improvement in the outcomes for future children and their mothers if fewer women smoked during pregnancy. Similarly, there are lifestyle changes the wider population could take to improve their health. However, the assumption underlying pressurised interventions such as routine carbon monoxide testing is that pregnant women are not making these changes because they require additional motivation to do so. The policy ignores the very premise it is based on. The NICE Guidelines state that women feel intense pressure to quit smoking during pregnancy and this is preventing them from engaging with measures aimed at improving their health and the health of their future children [38]. This indicates that the way to help women make healthy lifestyle choices during pregnancy is to alleviate this pressure. This would make them more likely to feel able to be open and honest with healthcare professionals and engage in a more supportive method of ensuring the best outcomes for their future children.

This is supported by evidence from a prenatal care programme founded by Jennie Joseph in America known as the JJ Way [30]. This programme aims to achieve positive pregnancy outcomes for all with particular efforts to reach low-income and marginalised people who are at risk of a poor birth outcome due to the social determinants of health and institutional and structural discrimination inherent in the health care system. The key to this approach to prenatal care is the empowerment of pregnant women:

Empowerment results from having access to high quality, cost efficient services, and a connection with supportive culturally-responsive services and natural supports which lead to an increase in knowledge, agency and self-determination [30].

This programme emphasises the importance of access to and engagement with, quality prenatal care. It seeks to move away from the paternalism evident in traditional maternity care where the pregnant woman is encouraged to trust the medical experts. The JJ Way encourages the pregnant woman to play an active role in her care, providing her with knowledge and support through peer educators and fluid group classes. Instead of viewing the pregnant woman and her future child as separate individuals whose interests may or may not align, the pregnant woman and her future child are viewed as a unit, with the understanding that the pregnant woman is the decision maker and has the full support of her care team [29].

As a result of this approach, the rate of preterm births in Orange County fell from 10% in 2015 to 4.3% in 2016 and the rate of low birthweight was reduced from 8.9% in 2015 to 5% in 2016/2017. By delivering prenatal care in this way the racial disparities in preterm birth outcomes were eliminated and there were significant reductions in low birthweight babies in at-risk populations [30].

In choosing how best to reduce prenatal harm the options presented here are (1) to target pregnant smokers with pressurised smoking cessation interventions and (2) to employ a supportive and empowering approach to prenatal care. The evidence suggests that even assuming that smoking cessation interventions stopped every pregnant woman smoking, the rates of prenatal harm would be reduced by 13% [57]. However, a supportive and empowering approach to prenatal care appears to reduce such harm by around 50% based on the evaluation of the JJ Way. This is even before we take into account the potential harms of pressurising pregnant women to stop smoking discussed above.Footnote 9 Therefore, if we are interested in harm reduction, this is a much more effective option.

Even though a greater reduction in prenatal harm could be achieved by addressing factors other than the behaviour of pregnant women, it could be argued that addressing factors such as social inequality and education are far more difficult and costlier than getting individuals to stop smoking. After all, smoking cessation measures are already part of our health service. However, this argument would not justify policies such as carbon monoxide screening as opposed to offering supportive, empowering prenatal care as prenatal care is already part of our health service. Placing a greater emphasis in that prenatal care on empowering pregnant women and supporting them to make decisions rather than policing their behaviour in a distrustful manner, would not be a particularly difficult or costly change. Indeed, it is in line with how many midwives already see their role [27].

It is not possible to employ both of these approaches simultaneously as the pressurised smoking cessation interventions would not fit within a supportive and empowering approach to prenatal care. However, employing a supportive and empowering approach to prenatal care has the added advantage of achieving the stated aim of carbon monoxide screening policy. If pregnant women are unlikely to admit that they smoke because of the extreme pressure they feel to stop smoking, it would be reasonable to expect that a supportive, non-judgmental approach to prenatal care would alleviate that pressure and thus remove the need for carbon monoxide screening. Therefore, it is clear that targeting the behaviour of pregnant women with pressurised smoking cessation interventions is not justified on the grounds of harm reduction, as more effective measures which are no more difficult to put into practice are available. Even if conditions 1, 2 and 3 had been met, the fact that an alternative, less problematic approach is available, would be sufficient to prevent the policy of routine carbon monoxide testing in pregnancy being justified on the ground of preventing prenatal harm to future children.

Conclusion

Does the evidence suggest that public health measures such as carbon monoxide testing in pregnancy are likely to achieve their aim of preventing harm to future children?

Despite the fact that smoking when not pregnant is harmful to the smokers and those around them, pregnant women are being singled out for a particular level of pressure to quit including being routinely tested for carbon monoxide at every antenatal appointment regardless of whether they say they smoke or not. Pressurising pregnant women to quit smoking is presented as necessary and proportionate in the interests of protecting future children from prenatal harm. This paper has examined the justification for such measures on the grounds of harm reduction. As stated above, for this to be the case four things would have to be established: (1) that smoking during pregnancy causes significant prenatal harm to future children; (2) that carbon monoxide testing reduces rates of smoking during pregnancy; (3) that such interventions do not cause more harm to future children than they prevent; and (4) that there is no other, less problematic way to reduce prenatal harm.

This paper has argued that while there is evidence connecting smoking during pregnancy to prenatal harm, there are other factors at play which prevent a clear causal link from being established. While reducing smoking during pregnancy is likely to have some beneficial impact on rates of prenatal harm, this is not the only way to achieve such a reduction. In fact, addressing other factors, such as social inequality, education, nutrition and the quality of prenatal care, would lead to a more significant reduction in rates of prenatal harm. Targeting pregnant women with pressurised smoking cessation measures such as carbon monoxide screening might help some women to quit smoking during pregnancy. However, even if carbon monoxide testing was 100% successful in getting women to quit smoking during pregnancy, the rates of prenatal harm would only fall by 13% [57] (compared to around 50% achieved by the JJ Way [30]) and this is without taking into account the potential harms of such interventions, for example, from women disengaging with prenatal care. Current discussions of the potential benefits of smoking cessation measures in pregnancy have not sufficiently taken into account the potential harms of such measures. As argued above, constructing the problem of prenatal harm as one of individual behaviour and targeting this behaviour with routine carbon monoxide testing has the potential to cause harm as it obscures other more significant causes of prenatal harm, risks women disengaging with prenatal care and does not promote the autonomy of pregnant women. Perhaps the most troubling aspect is that routine carbon monoxide testing sends a message to pregnant women that they cannot be trusted either to truthfully answer questions as to whether or not they smoke, or to make decisions in the best interests of themselves and their future children in the way that non-pregnant individuals are. Extra pressure is thought to be required for pregnant women to quit smoking as they will not be able to make an appropriate decision when presented with information about the risks and appropriate support if requested. This distrust is defended on the basis of the extra pressure pregnant women face, but instead of alleviating this pressure, the policy exacerbates it, risking alienating pregnant women from their prenatal care team. Crucially, as such a policy is incompatible with a supportive and empowering approach to prenatal care, it is an obstacle to measures being put into place which the evidence suggests would significantly reduce prenatal harm. Far from being justified on the grounds of harm reduction, the policy to routinely test pregnant women for carbon monoxide has the potential to do more harm than good and there are other, more effective, less problematic ways to reduce harm to future children.

Notes

Carbon monoxide tests have been used on non-pregnant smokers in Hertfordshire but this has so far been limited to individuals who say they are smokers and are required to quit before being permitted surgery on the NHS. While this is also problematic, it is not the same as testing all patients regardless of whether they say they smoke or not. See [51].

Other measures include, the promotion of smoke free homes during pregnancy and beyond. Such measures could potentially avoid some of the problems associated with the policy of singling out pregnant women for routine carbon monoxide screening [36].

There is currently no evidence regarding the extent to which NICE Guidelines on smoking cessation during pregnancy have been implemented nationally but the policy has been adopted by a number of NHS Trusts including South Tees NHS Foundation Trust [52], South Warwickshire NHS Foundation Trust [53], NHS Scotland [40] and NHS Wales [44] among others.

As the policy under consideration is a public health measure, this paper assesses harm on the basis of rates of children born classified as being of low birthweight, stillborn or born preterm.

This weakness in supporting evidence can similarly be seen for the causal link between alcohol consumption during pregnancy and Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. One study found that “women who consumed at least three alcoholic drinks a day but ate balanced diets experienced a rate of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) of only 4.5 percent, while women who drank the same amount and were malnourished had an FAS rate of 71 percent [8] (It was also found that the rate of FAS in children born to chronic alcoholic mothers in lower socioeconomic classes (defined as labourers and unskilled workers) was 70.9% compared to 4.5% in those born to mothers in higher socioeconomic classes such as clerical and sales workers [8] See also [1].

Based on [15].

This study also found that in one hospital where auxiliary nurses were responsible for performing the test, 89% of women provided a breath sample at the initial booking appointment, whereas in a hospital where midwives were responsible for carbon monoxide testing, only 35% of women provided a sample. This indicates that the policy is unlikely to achieve its potential of identifying 94% of pregnant smokers when the test is the responsibility of midwives, perhaps due to time constraints or other priorities for midwives delivering antenatal care. [35].

While there may be potential consequential harms to pregnant women in employing policies such as routine carbon monoxide screening, the question being considered is whether such policies are justified on the basis that they reduce prenatal harm to future children. Therefore, this section will focus on the potential harms to the future children they seek to protect.

Pers-Anders Tengland has argued that there are moral reasons for preferring the empowerment approach to health promotion rather than the behaviour change approach [55].

References

Abel, E. L. (1995). An update on incidence of FAS: FAS is not an equal opportunity birth defect. Neurotoxicology and Teratology, 17(4), 437–443.

Abu-Saad, K., & Fraser, D. (2010). Maternal nutrition and birth outcomes. Epidemiologic Reviews, 32(1), 5–25.

Adhikari, R., & Sawangdee, Y. (2011). Influence of women’s autonomy on infant mortality in Nepal. Reproductive Health, 8(1), 1.

Allen, F., Gray, R., Oakley, L., Kurinczuk, J. J., Brocklehurst, P., & Hollowell, J. (2009). The effectiveness of interventions targeting major potentially modifiable risk factors for infant mortality: A user’s guide to the systematic review evidence. National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit: University of Oxford.

Ashwin, C., Marshall, J., & Standen, P. (2012). Exploring women’s experiences of smoking during pregnancy and the postpartum. Evidence Based Midwifery, 10(4), 112.

Bewley, S. (2002). Restricting the freedom of pregnant women. maternal–fetal medicine, 131.

Bille, C., & Andersen, A.-M. N. (2009). Preconception care. British Medical Journal (Online), 338.

Bingol, N., Schuster, C., Fuchs, M., Iosub, S., Turner, G., Stone, R. K., et al. (1987). The influence of socioeconomic factors on the occurrence of fetal alcohol syndrome. Advances in Alcohol and Substance Abuse, 6(4), 105–118.

Blair, P. S., Fleming, P. J., Bensley, D., Smith, I., Bacon, C., Taylor, E., et al. (1996). Smoking and the sudden infant death syndrome: Results from 1993–5 case-control study for confidential inquiry into stillbirths and deaths in infancy. Confidential enquiry into stillbirths and deaths regional coordinators and researchers. British Medical Journal, 313(7051), 195–198.

Bloch, M., & Parascandola, M. (2014). Tobacco use in pregnancy: A window of opportunity for prevention. The Lancet Global Health, 2(9), 489–490.

Boutwell, B. B., & Beaver, K. M. (2010). Maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy and offspring externalizing behavioral problems: A propensity score matching analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 7(1), 146–163.

Brazier, M. (1999). Liberty, maternity, responsibility. Current Legal Problems, 52, 359.

Brione, R. (2015). To what extent does or should a woman’s autonomy overrule the interests of her baby? A study of autonomy-related issues in the context of caesarean section. The New Bioethics, 21(1), 71–86.

Bryce, A., Butler, C., Gnich, W., Sheehy, C., & Tappin, D. M. (2009). CATCH: Development of a home-based midwifery intervention to support young pregnant smokers to quit. Midwifery, 25(5), 473–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2007.10.006.

Button, T. M. M., Maughan, B., & McGuffin, P. (2007). The relationship of maternal smoking to psychological problems in the offspring. Early Human Development, 83(11), 727–732.

Campbell, D. (Sunday 26 February, 2017 00.03 GMT). Test all pregnant women for smoking, say NHS chiefs. The Guardian,

Chamberlain, C., O’Mara-Eves, A., Porter, J., Coleman, T., Perlen, S. M., Thomas, J., et al. (2017). Psychosocial interventions for supporting women to stop smoking in pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2).

Coulter, A., & Ellins, J. (2007). Effectiveness of strategies for informing, educating, and involving patients. British Medical Journal, 335(7609), 24–27.

Day, J., Savani, S., Krempley, B. D., Nguyen, M., & Kitlinska, J. B. (2016). Influence of paternal preconception exposures on their offspring: Through epigenetics to phenotype. American Journal of Stem Cells, 5(1), 11–18.

Department of Health. (2007). Review of the Health Inequalities Infant Mortality PSA Target. London: Department of Health.

Entwistle, V. A., Cribb, A., & Owens, J. (2018). Why health and social care support for people with long-term conditions should be oriented towards enabling them to live well. Health Care Analysis, 26(1), 48–65.

Fresh NE (2017). Major initiative to protect unborn babies from smoking in the North East. http://www.freshne.com/in-the-news/pr/item/1974-major-initiative-to-protect-unborn-babies-from-smoking-in-the-north-east. Accessed 8 November 2017.

FreshSFNE (2017). Smoking in pregnancy. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Icc3NwP-gU&list=UU2lnzX6fEhIckkzI1amNs2Q&index=9. Accessed 8 November 2017.

Friesen, P. (2016). Personal responsibility within health policy: Unethical and ineffective. Journal of Medical Ethics, 44, 53–58.

Green, N. S., Damus, K., Simpson, J. L., Iams, J., Reece, E. A., Hobel, C. J., et al. (2005). Research agenda for preterm birth: Recommendations from the March of Dimes. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 193(3), 626–635.

Greenway, J. C., & Entwistle, V. A. (2013). Ethical tensions associated with the promotion of public health policy in health visiting: a qualitative investigation of health visitors’ views. Primary Health Care Research and Development, 14(2), 200–211.

High Quality Midwifery Care (2014). London: The Royal College of Midwives.

Jackson, E. (2001). Regulating reproduction: Law, technology and autonomy. Bloomsbury: Bloomsbury Publishing.

JJ Way - Commonsense Childbirth Inc. http://www.commonsensechildbirth.org/jjway/. Accessed 27 April 2018.

Josephs, L., & Brown, S. E. (2017). The JJ Way: Community-based Maternity Center Final Evaluation Report. Visionary Vanguard Group Inc.

Juárez, S. P., & Merlo, J. (2013). Revisiting the effect of maternal smoking during pregnancy on offspring birthweight: A quasi-experimental sibling analysis in Sweden. PLoS ONE, 8(4), e61734.

Kabir, Z., Connolly, G. N., Clancy, L., Cohen, B. B., & Koh, H. K. (2009). Declining maternal smoking prevalence did not change low birthweight prevalence in Massachusetts from 1989 to 2004. The European Journal of Public Health, 19(1), 65–68.

Kukla, R. (2008). Measuring mothering. International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics, 1(1), 67–90.

Lumley, J., Chamberlain, C., Dowswell, T., Oliver, S., Oakley, L., & Watson, L. (2009). Interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3).

McGowan, A., Hamilton, S., Barnett, D., Nsofor, M., Proudfoot, J., & Tappin, D. M. (2010). ‘Breathe’: The stop smoking service for pregnant women in Glasgow. Midwifery, 26(3), e1–e13.

Morgan, H., Treasure, E., Tabib, M., Johnston, M., Dunkley, C., Ritchie, D., et al. (2016). An interview study of pregnant women who were provided with indoor air quality measurements of second hand smoke to help them quit smoking. Bmc Pregnancy and Childbirth, 16(1), 305.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2010). Weight management before, during and after pregnancy. NICE Guideline PH27.

National Institute for Heath and Clinical Excellence (2010). Smoking: Stopping in pregnancy and after childbirth. NICE Guideline PH26.

Nelson, E. (2013). Law, policy and reproductive autonomy. Bloomsbury: Bloomsbury Publishing.

NHS Health Scotland Ready Steady Baby! Tests and checks you may have. http://www.readysteadybaby.org.uk/you-and-your-pregnancy/antenatal-care/tests-and-checks-you-may-have.aspx. Accessed 15 November 2018.

NHS Smokefree NHS. https://www.nhs.uk/smokefree/help-and-advice. Accessed 8 November 2017.

O’Connell, M., & Duaso, M. (2014). Barriers and facilitators of midwives’ use of the carbon monoxide breath test for smoking cessation in practice: a qualitative study. Midirs Midwifery Digest, 24(4), 453–458.

Pickett, K. E., & Wilkinson, R. G. (2015). Income inequality and health: A causal review. Social Science and Medicine, 128, 316–326.

Public Health Wales NHS Trust (2015). Models for access to maternal smoking cessation support. http://www.wales.nhs.uk/sitesplus/documents/888/PHW%20MAMSS%20Report%20E%2003.17.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2018.

Robertson, J. A. (1983). Procreative Liberty and the control of conception, pregnancy, and childbirth. Virginia Law Review, 69(3), 405–464.

Salihu, H. M., Aliyu, M. H., Pierre-Louis, B. J., & Alexander, G. R. (2003). Levels of excess infant deaths attributable to maternal smoking during pregnancy in the United States. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 7(4), 219–227.

Savitz, D. A., Schwingl, P. J., & Keels, M. A. (1991). Influence of paternal age, smoking, and alcohol consumption on congenital anomalies. Teratology, 44(4), 429–440.

Scott, R. (2000). Maternal duties toward the unborn? Soundings from the law of tort. Medical Law Review, 8(1), 1–68.

Scott, R. (2002). Rights, duties and the body: law and ethics of the maternal-fetal conflict. Oxford: Hart Publishing.

Sharma, A., & Kader, M. (2013). Effect of women’s decision-making autonomy on infant’s birth weight in rural. Bangladesh: ISRN Pediatrics.

Siddique, H. (Wednesday 18 October, 2017). Doctors to breathalyse smokers before allowing them NHS surgery. The Guardian,

South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (2013). Major initiative to tackle smoking in pregnancy underway. https://www.southtees.nhs.uk/news/health-improvement/major-initiative-tackle-smoking-pregnancy-underway/. Accessed 15 November 2018.

South Warwickshire NHS Foundation Trust NHS Warwickshire Stop Smoking in Pregnancy Service. https://www.swft.nhs.uk/our-services/adult-hospital-services/maternity/nhs-warwickshire-stop-smoking-pregnancy-service. Accessed 15 November 2018.

Stanton, C., & Cave, E. (2015). Maternal responsibility to the child not yet born. In C. Stanton, S. Devaney, A.-M. Farrell, A. Mullock, & M. Brazier (Eds.), Pioneering healthcare law: Essays in honour of Margaret Brazier. London: Routledge.

Tengland, P.-A. (2016). Behavior change or empowerment: On the ethics of health-promotion goals. Health Care Analysis, 24(1), 24–46.

The Law Commission (1974). Report on Injuries to Unborn Children (Law Com. No. 60). Advice to the Lord Chancellor under section 3(1)(E) of the Law Commissions Act 1965, 20th Century House of Commons Sessional Papers, 1974, Vol. VII, 1021.

Tominey, E. (2007). Maternal smoking during pregnancy and early child outcomes. CEP Discussion Paper No 828: Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics.

Turner-Warwick, M. (1992). Smoking and the young: A report of a working party of the Royal College of Physicians. Tobacco Control, 1(3), 231–235.

UK Chief Medical Officer (2016). UK Chief Medical Officers’ Low Risk Drinking Guidelines.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bowden, C. Are We Justified in Introducing Carbon Monoxide Testing to Encourage Smoking Cessation in Pregnant Women?. Health Care Anal 27, 128–145 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10728-018-0364-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10728-018-0364-z