Abstract

Optimizing agronomic efficiency (AE) of nitrogen (N) fertilizer use by crops and enhancing crop yields are challenges for tropical no-tillage systems since maintaining crop residues on the soil surface alters the nutrient supply to the system. Cover crops receiving N fertilizer can provide superior biomass, N cycling to the soil and plant residue mineralization. The aims of this study were to (i) investigate N application on forage cover crops or cover crop residues as a substitute for N sidedressing (conventional method) for maize and (ii) investigate the supply of mineral N in the soil and the rates of biomass decomposition and N release. The treatments comprised two species, i.e., palisade grass [Urochloa brizantha (Hochst. Ex A. Rich.) R.D. Webster] and ruzigrass [Urochloa ruziziensis (R. Germ. and C.M. Evrard) Crins], and four N applications: (i) control (no N application), (ii) on live cover crops 35 days before maize seeding (35 DBS), (iii) on cover crop residues 1 DBS, and (iv) conventional method (N sidedressing of maize). The maximum rates of biomass decomposition and N release were in palisade grass. The biomass of palisade grass and ruzigrass were 81 and 47% higher in N application at 35 DBS compared with control in ruzigrass (7 Mg ha−1), and N release followed the pattern observed of biomass in palisade and ruzigrass receiving N 35 DBS (249 and 189 kg N ha−1). Mineral N in the soil increased with N application regardless of cover crop species. Maize grain yields and AE were not affected when N was applied on palisade grass 35 DBS or 1 DBS (average 13 Mg ha−1 and 54 kg N kg−1 maize grain yield) compared to conventional method. However, N applied on ruzigrass 35 DBS decreased maize grain yields. Overall, N fertilizer can be applied on palisade grass 35 DBS or its residues 1 DBS as a substitute for conventional sidedressing application for maize.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Long-term agricultural projections report that the world’s population is growing at a rate of at least one percent per year (USDA 2019; Worldometers 2019). Historically, solutions for meeting the increasing demand for food have emphasized the expansion of cultivated areas, but recently the focus has shifted to increasing yields within existing agricultural systems. Introduction of cover crops into a no-tillage (NT) system has been proposed as an approach to increase yields of cash crops, agronomic efficiency (AE) of N fertilizer applied, and system sustainability (Habbib et al. 2016). The maintenance of cover crop residues under NT system has more positive than negative effects. Although residues under NT can immobilize N in the soil and carry over plant diseases, an appropriate crop rotation in the NT system is more economical than tilling in reducing machinery and equipment costs, and supports higher crop yields through improvements of soil fertility and nutrient cycling in the long-term (Derpsch et al. 2014; Turmel et al. 2015; Camarotto et al. 2018). Crop residues cycle nutrient-replenishing soil organic matter and prevent soil erosion (Coleman et al., 2018). The choice of species used as a cover crop determines the dynamics of carbon (C) and N within the system and thus nutrient cycling (Aita et al. 2004; Coleman et al. 2018). Plants of the genus Urochloa are commonly used as cover crops in the tropical region due to their high biomass and vigorous, deep root systems (Pacheco et al. 2011; Soratto 2011; Moro et al. 2013). This deep root architecture increases nutrient uptake from the soil and enables these species to grow in harsh off-season conditions such as drought (Felismino et al. 2012; Pacheco et al. 2017). In addition, the residues of Urochloa spp. offer other benefits, such as improved soil health, weed suppression and nutrient loss avoidance (Castro et al. 2015; Büchi et al. 2019).

Nitrogen fertilizer application may maximize the absolute biomass yield of cover crops. Efficient N application improves the sustainability of food-producing systems by preventing loss of excess N through nitrate (NO3−–N) leaching and nitrous oxide emission. Planning N fertilization by accounting for the decomposition of cover crops and N release can improve the economic yield produced per unit of N fertilizer applied from subsequent crop to produce grains, i.e., the increase of N-use efficiency (Oenema et al. 2015; Bani, 2018). The N available from cover crops depends on biomass mineralization by microorganisms (Gatiboni et al. 2011; Liu and Sun 2013). The N quantity, quality and amount of biomass affect the rate of decomposition and consequently the synchronism of N release and N demand by the next crop. Residues with high C/N ratios may reduce N availability through immobilization. Few studies examining synchronism of N release from plant residues with crop demand have been performed under tropical climates (Cantarella 2007; Rosolem et al. 2017).

Maize crops require high quantities of N to increase grain yields and the soils alone do not generally supply the total N that the plants need to achieve yield increases (Ciampitti and Vyn 2012). The conventional recommendation for N fertilizer in maize is to split the application: up to 30 kg N ha−1 at planting and 140–180 kg N ha−1 at sidedressing when maize has 5–7 leaves (Cantarella et al. 1997). However, N fertilizer is often applied excessively and the excess N can be lost and have a negative effect on the environment (Soares et al. 2016). One solution to this problem would be combine the timing of fertilizer application with use of cover crops to control the N release to the subsequent crops and thus improve the fertilizer efficiency. In addition, the early application of N on cover crops could provide flexibility in the operational schedules of farmers and facilitate the fertilizer management of the main crop since sidedress N application has to be applied during a certain growth stage of a plant and the equipment used often causes leaf damage (Schepers and Raun 2008).

A previous study showed that the early application of total-N fertilizer rate on live cover crops or its residues before cash crop seeding was not sufficient to meet the N demand of maize as the conventional method of N application (Momesso et al. 2019). The conventional method for applying N fertilization is to split the fertilizer rate by 25% at maize seeding plus 75% at maize growth stage sidedressing (Cantarella et al. 1997). However, the N fertilizer application at maize growth stage can favor N loss through NO3−–N leaching by high rainfall in tropical region (Panison et al. 2019; Galdos et al. 2020). Thus, an alternative and sustainable way to use N fertilizers could be to follow the initial recommended application of N fertilizer at maize seeding and, instead of following the second recommended application method (at maize growth stage), the N could be applied earlier on live cover crops or on cover crop residues (Momesso et al., 2020). This N application on live cover crops or cover crops residues may be a good alternative for sidedress N application (conventional method). Since maize demands high amounts of N and grass cover crops can cause temporary N immobilization, it was hypothesized that N application on live cover crops or over the cover crop residues could replace the sidedress N application (conventional method) as alternative N management and increase maize grain yields and AE of N by maize. To test these hypotheses, we used a three-years experiment of N applied on live cover crops (palisade grass and ruzigrass), residues and conventional N application method to subsequent maize. This study aimed to measure dry matter (DM) yield, biomass persistence and N release of two forage grasses grown fertilized with N, and to assess the effects of N application on live grass or cover crop residues on soil N content, and maize grain yield and AE of N.

Material and methods

Field experimental characterization and experimental setup

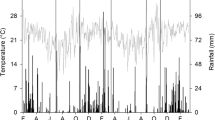

The experiment was conducted over three consecutive seasons from 2015 to 2018, in Botucatu, São Paulo, Brazil (48° 26′ W, 22° 51′ S, 740 m above sea level). The regional climate, according to the Köppen classification, is Cwa, i.e., with dry winter, and warm and wet summer. Annual rainfall is 1358 mm and the average annual minimum and maximum temperatures are 15.3 and 26.1 °C, respectively. During the experiment, rainfall and temperature were recorded on a meteorological station located nearby the site (Supplementary Fig. 1). The soil is a clay, kaolinitic, thermic Typic Haplorthox (Soil Survey Staff 2014), with 630, 90 and 280 g kg−1 of clay, silt, and sand, respectively. Selected chemical characteristics of the top soil (0.0–0.20 m) are in Supplementary Table 1. The experimental area had been cropped under no-till for 9 years before the experiment and the historical crop rotation is shown in Supplementary Table 2.

The experiments were conducted in a 2 × 4 factorial design in randomized blocks with four replicates. The treatments consisted of two cover crop species: palisade grass (Urochloa brizantha cv. Marandu) and ruzigrass (U. ruziziensis cv. Ruziziensis), and four N management strategies (N application timing): (i) control (no N application), (ii) 120 kg N ha−1 broadcast over the live grass cover crop 35 days before maize seeding (DBS) (5 days before cover crop termination), (iii) 120 kg N ha−1 broadcast over terminated grass cover crop 1 day before seeding of maize (pre-seeding of maize), and (iv) 120 kg N ha−1 sidedressed at V4 growth stage (four expanded leaves) of maize [conventional method, recommended by Cantarella et al. (1997)]. In all treatments, except for the control, 40 kg N ha−1 was sub-surface banded applied between 0.05 and 0.10 m next to the seed row, amounting to 160 kg N ha−1, applied as ammonium sulfate. Nitrogen rate was based on the recommendation of the Technical Fertilization and Liming Recommendations (Cantarella et al. 1997), for applying N fertilizer to maize (Maize yield = 10–12 Mg ha−1 and low–high expected response to N) is 100 to 170 kg N ha−1. The plots were 4.5 m wide and 8.0 m long and at each end of each plot 1.0 m was considered as buffer.

Cover crop and maize management

The grasses were sown at a density of 10 kg ha−1 seed (34% viable seeds) without fertilizer. In all growing seasons, the cover crops were grown approximately eight months from April to November (off-season). The cover crops were 0.50 m tall and were cut 30 days before desiccation 0.30 m above soil level by mechanical mowers to stimulate growth and N uptake by cover crops. The mowed material was left on the soil surface.

The first N application was carried out on green cover crops at 35 DBS of maize in October of each year (Supplementary Fig. 1). Then 5 days later, the cover crops were desiccated with glyphosate at 1.56 kg ha−1 (a.i.). The second N application was carried out over the cover crop straws 1 DBS of maize in November. The hybrid maize used was P3456 Pioneer (2019) and row spacing of 0.45 m (3 seeds m−1), seeded 30 days after cover crop termination at a density of 65,000 seeds ha−1, and all N treatments received 40 kg ha−1 of N applied next to the seed line. The conventional method of N fertilizer was sidedress N applied in single-side surface banding (0.5 mm away from the maize row) when maize was at the V4 growth stage. No N fertilizer was applied to the control in December. The time from maize planting to physiological maturity was approximately 130 days after plant emergence. Maize was harvested 7 days after physiological maturity from a 10.8 m2 area in each plot using a mechanical harvester.

Cover crop dry matter and N accumulation

Samples of cover crops dry matter were taken on 0 (day of cover crop termination), 30, 60, 90 and 120 days after termination (DAT) of cover crop. Three 0.25 m2 sub-samples were taken per plot using a rigid quadrat. Sampling was performed at random points along diagonal crosswise lines, excluding 1.0 m at either end (border). Fresh samples were oven-dried at 65 °C, weighed for dry-weight determination, and ground in a Wiley mill (Thomas Scientific® Wiley Mills) to pass through a 0.5-mm sieve. Subsamples were used to determine N concentrations determination on an elemental analyzer (LECO-TruSpec® CHNS). Total accumulated within dry matter samples were extrapolated to Mg ha−1.

Ammonium and nitrate content in the soil

Soil samples (0–0.20 m depth) were collected at cover crop termination, and 30, 60 and 90 DAT for determination of ammonium (NH4+–N), NO3−–N and total-N. Samples were taken with a 0.25 m diameter auger. To stop soil N transformations, the samples were put in plastic bags and conditioned in a freezer at − 20 °C. The NH4+–N and NO3−–N were extracted with KCl and distilled (Keeney and Nelson 2006). For total-N content, samples were air-dried, ball milled, and analyzed with an elemental analyzer (LECO-TruSpec® CHNS), using 0.2 g of soil.

Maize sampling and N agronomic efficiency

Maize leaf samples and shoot dry matter were collected when 50% of the plants were at full flowering stage (silking) by taking 5 whole plants per plot. The samples were chopped and dried in a forced-air oven at 65 °C for 72 h and weighed for shoot dry matter. Dried samples were digested with sulfuric acid for N concentration determination, and with a nitro-perchloric (HNO3 + HClO4) solution for P, K, Ca, Mg, and S. Then, concentrations of N, P, K, Ca, Mg, and S in the leaves were determined according to the methods of Malavolta et al. (1997). Nitrogen concentration was determined using the semi-micro-Kjeldahl distillation method, P was determined by colorimetry method, S was determined by turbidimetry method, and K, Ca and Mg were determined using atomic absorption spectrophotometry.

At maize harvest, kernel weight was determined, and data were transformed to grain yield ha−1 at 130 g kg−1 moisture content. Final plant population (the number of plants in the four central rows of the 6-m rows in each plot) was determined by extrapolated data to hectare, and number of ears per plant, number of kernels per ear, and weight of 100 kernels were evaluated from 10 plants per plot chosen at random. The AE of applied N, i.e., N-use efficiency, in kg grain kg−1 N, was calculated for each N-fertilized treatment. The AE refers to the ratio of the difference between the maize grain yield in a N-fertilized treatment and the grain yield of the control (No N), to the amount of N-fertilizer applied in the specific treatment in kg N ha−1, i.e., the kg of maize grain yield obtained per kg of N applied, according to the equation (Eq. (1)) (Dobermann, 2005; Fageria and Baligar, 2005):

Data statistical analyses

All data from cover crops (dry matter and amount of N accumulated) were first tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test procedure and were distributed normally (W ≥ 0.90). Then, dry matter and N accumulated of cover crops were submitted to ANOVA (P ≤ 0.05) to determine the effect of growing season, cover crop, N application timing, and their interactions. There were no significant (P ≤ 0.05) effect of growing seasons interactions with cover crop and N application timing for any of the dependent variables. Therefore, data were combined across growing seasons to improve robustness of model fits. Second, analysis of cover crop, N application timing, sampling time (0, 30, 60, 90 and 120 DAT), and their interaction were performed and considered fixed effects. Block was a random variable. Regressions of variables of the five sampling times were tested across the replication. Effects were considered significant at P < 0.05 and all data were fit to the non-linear model utilizing exponential mathematical model (Paul and Clark, 1989) with the following exponential equation (Eq. (2)) in R v4.02 (R Core Team 2019; Pinheiro et al., 2020):

where Xt = dry matter or N accumulated of cover crop at time t, X0 = dry matter or N accumulated at day after cover crop termination, k = constant of residue decomposition or N release, and DAT = days after cover crop termination. Additionally, the half-life time was calculated using the k (t½ = 0.693/k) (Paul and Clark, 1989).

Data from soil (NH4+–N, NO3−–N and total-N content) and maize (shoot dry matter, yield components, grain yield and AE) were initially tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test procedure using the statistical software R (version 3.5.2). All data were distributed normally (W ≥ 0.90). Cover crop, N application timing and growing season were considered fixed factors. The growing seasons and their interactions with cover crop and N application timing were not significant at P < 0.05 for any of the dependent variables. Thus, the data for the three growing seasons were combined. The block variable was considered a random variable. Analysis of variance and F probability test were performed in these variables. Comparison of means was performed with LSD test (P ≤ 0.05) when the F-test t was significant.

Results

Biomass mineralization and N release from plant residues

The dry matter loss and N accumulated from palisade grass and ruzigrass was significantly (p < 0.05) affected by N application timing on cover crops at 0, 30, 60, 90 and 120 DAT (Table 1, Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 3). On the day of cover crop termination (0 DAT), N application on palisade grass at 35 DBS had the highest biomass (13.8 Mg ha−1) and N accumulated (250 kg ha−1), whereas the lowest biomass (8.7 Mg ha−1 on average) and N accumulated (120 kg ha−1 on average) were on the ruzigrass at 1 DBS, conventional and control (without N application) (Table 1; Fig. 1). Palisade grass resulted in similar rates of dry matter loss and N accumulated in all treatments when receiving N fertilizer (35 DBS, 1 DBS and conventional) and no-N (control). Ruzigrass receiving N at 35 DBS had similar rate of dry matter loss and N accumulated to that of palisade grass, and the highest rate compared to that of other ruzigrass treatments (1 DBS, conventional and control). From 0 to 120 days after cover crops termination, the dry matter loss and N accumulated of palisade grass at 35 DBS were 20% and 27% higher in all N treatments compared with palisade grass control (6.1 Mg ha−1 and 162 kg ha−1 of dry matter and N release, respectively) (Fig. 1). For ruzigrass, dry matter loss and N accumulated followed the pattern observed in treatments with palisade grass and the lowest amounts of dry matter loss and N accumulated were 3.61 Mg ha−1 and 59 kg N ha−1, respectively, found for ruzigrass with zero-N fertilizer. In addition, decay constant, k, indicated the pattern that decomposition rates decreased from 0.007 and 0.015 for the dry matter loss and N accumulated, respectively, of palisade grass receiving N 35 DBS to a minimum of 0.004 and 0.006 for ruzigrass receiving zero-N fertilizer (Table 1). Both cover crops at 35 DBS promoted a half-life of 99 and 87 days in palisade grass and ruzigrass, respectively.

Decomposition of biomass yield (a), and amount of N accumulated in straw (b) of palisade grass and ruzigrass as affected by N application timing over days after cover crop termination. Data are average of three growing seasons and symbols represent mean values. Nitrogen application timing treatments are as follows: 35 DBS: 120 kg N ha−1 broadcast over cover crop 35 days before maize seeding plus 40 kg N ha−1 in the maize seeding furrow; 1 DBS: 120 kg N ha−1 broadcast over crop 1 day before maize seeding plus 40 kg N ha−1 in the maize seeding furrow; Conventional method: 40 kg N ha−1 in the maize seeding furrow plus 120 kg N ha−1 sidedressed in V4 growth stage of maize; and Control: no N application. Error bars are one standard error from the mean

Soil NH4 +–N, NO3 −–N and total-N content

No interaction of cover crop, N application timing and growing season on the N forms in soil were observed in the 0–0.20 m soil profile, except for NO3−–N content at 0 DAT (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 4). Significant differences between palisade grass and ruzigrass on soil NH4+–N content at 0, 30, 60 DAT were not observed for in soil NH4+–N content on day of cover crop termination (0 DAT), which soil with palisade grass and ruzigrass had highest NH4+–N content in N application at 35 DBS (Fig. 2a). At 0 DAT, the NO3−–N content in the soil increased in ruzigrass, regardless N application timing; whereas only palisade grass when N applied at 35 DBS had similar values to ruzigrass (Fig. 2b). The total-N content in the soil followed the pattern of the soil NH4+–N (Fig. 2c).

Cover crop × N application timing interaction effect on NH4+–N (a), NO3−–N (b) and total-N (c) content in the soil at depth of 0–0.20 m at 0, 30, 60 and 90 days after cover crop termination (DAT). Data are average of three growing seasons. Treatments are described in Fig. 1. One letter: different lowercase letters denote significant differences between cover crops and N application timing interaction; two letters: different lowercase letters denote significant differences between cover crops and different uppercase letters denote significant differences among N application timing; ns: no statistically significant difference (LSD, P ≤ 0.05)

On the day of maize seeding (30 DAT), highest N mineral (NH4+–N and NO3−–N content) was observed on both cover crops with N applied 35 DBS and 1 DBS (Fig. 2a and b). In addition, soil cultivated with ruzigrass had lowest NH4+–N content at this time. No influence of cover crops and N application timing was observed on the total-N content in the soil at 30 DAT (Fig. 2c). At 60 days after termination, NH4+–N content was greater in soil after palisade grass and ruzigrass receiving N fertilizer at conventional method. Meanwhile, there were no differences neither in NO3−–N nor in total-N content among cover crops with different N application times. At maize harvest (120 DAT), a time point at which no-N fertilizer was applied, times of N application on cover crops did not affect mineral- and total-N in the soil (Fig. 2a–c).

Maize crop response

The leaf N concentration, shoot dry matter, yield components, grain yields and AE of maize are shown in Supplementary Table 5 and Fig. 3. Cover crops significantly affected only shoot dry matter and plant population (Supplementary Table 5). Maize cultivated after palisade grass had higher shoot dry matter and lower plant population than ruzigrass (Fig. 3b and c). For both cover crops, maize showed statistically similar shoot dry matter and plant population when N fertilizer was applied (35 DBS, 1 DBS and conventional), while the lowest shoot dry matter and plant population were in maize receiving zero-N fertilizer.

Cover crop × N application timing interaction effect on N concentrations at maize flowering (a), shoot dry matter (b), plant population (c), number of ears per plant (d), number of kernels per ears (e), 100-kernel weight (f), grain yield (g), and N agronomic efficiency (h) of maize. Data are average of three growing seasons. Treatments are described in Fig. 1. One letter: different lowercase letters denote significant differences between cover crops and N application timing interaction; two letters: different lowercase letters denote significant differences between cover crops and different uppercase letters denote significant differences among N application timing; ns: no statistically significant difference (LSD, P ≤ 0.05)

The interaction of cover crops and N application timing had a significant influence on leaf N concentration, number of kernels per ear, 100-kernel weight, grain yield and AE (Supplementary Table 5 and Fig. 3). Nitrogen applications (35 DBS, 1 DBS, conventional) resulted in a higher N concentration in maize leaves compared with the control (Fig. 3a). Maize following both palisade grass and ruzigrass had the highest number of kernels per ear when N was applied both 1 DBS and conventionally; palisade grass had higher number of kernels per ear (676, on average) than ruzigrass (630, on average) (Fig. 3e). The 100-kernel weight did not follow the pattern of number of kernels per ear (Fig. 3b). Maize cultivated after palisade grass had greater 100-kernel weight of maize when N was applied at 35 DBS and conventional method of application; while 100-kernel weight was lowest when maize cultivated in succession to ruzigrass with no N-fertilizer.

Maize following palisade grass resulted in a 25% increase in grain yield compared to maize following ruzigrass (9.4 Mg ha−1) (Supplementary Table 5 and Fig. 3g). Nitrogen fertilizer applied on palisade grass (35 DBS, 1 DBS and conventional) resulted in highest grain yields of maize, achieving an average of 13.4 Mg ha−1 (Fig. 3g). For ruzigrass, the response of grain yield varied significantly with N application timing, the highest yield maize was in maize cultivated after ruzigrass at 1 DBS and conventional (11.1 and 10.9 Mg ha−1, respectively). Agronomic efficiency of maize followed the pattern of grain yield (Fig. 3g and h). Maize cultivated after palisade grass had higher AE than ruzigrass. Maize had similar AE in the treatment with palisade grass receiving N fertilizer (35 DBS, 1 DBS, and conventional), which resulted on average 54 kg of maize grain yield obtained per kg of N applied, regardless of N application timing. In contrast, the highest AE was in maize cultivated after ruzigrass that received N fertilizer at 1 DBS and conventional method (46 and 44 kg of maize yield per kg of N applied, respectively), compared to N applied 35 DBS.

Discussion

Effect of early N application on biomass mineralization and N release from cover crops

The earlier N application on both cover crops stimulated, as expected, the increase in biomass and N accumulated in the residues by palisade grass and ruzigrass, in which palisade grass was among the largest producer of biomass. Grasses of the genus Urochloa, especially palisade grass, have high potential for dry matter yield and nutrient cycling compared with other cover crops such as sun hemp (Crotalaria juncea) and pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) (Fisher et al. 1995; Borghi et al. 2013; Baptistella et al. 2020). Several studies have highlighted differences among Urochloa spp. and their dry matter yields of forage grasses and the response of forage in increasing biomass by N fertilizer application (Pacheco et al. 2011, 2013; Momesso et al. 2019; Tanaka et al. 2019). Additionally, the adequate weather conditions benefit the great biomass yield of Urochloa spp. grown such as observed in 2015/2016 growing season (Supplementary Fig. 1), which can favor the straw amount for decomposition and nutrient release for subsequent cash crop. The superior biomass yield of palisade grass related to ruzigrass, even with N fertilization, is explained by plant characteristics of its easy adaptation, great seasonal distribution and high responsiveness to N application (Fisher et al. 1995). Although N fertilizer on live palisade grass led to the increase of its biomass, the timing of N fertilizer application on living cover crops or on cover crop residue altered the decompositions rates which are essential for N supply to the subsequent crop in the agricultural system.

Palisade grass with N fertilizer had the ability to uptake and assimilate N, and thus release high amounts of biomass and N by decomposition in the tropical no-tillage system. Understanding the dynamics of residues, N release and the half-life of plant residue during cover crops straw decomposition gives insights on how cover crops provide nutrients to soil and synchronize residue decomposition and N demand of the growing maize (Jahanzad et al. 2016). Although there are debates of herbicides use for terminating cover crops, countless benefits of terminated cover crop residue have been observed to slow the evolution of weed herbicide resistance, minimize soil erosion, and increase soil organic matter (SOM) and nutrient cycling by maintaining residue on the soil surface (Castro et al. 2015; Büchi et al. 2019; Rosario-Lebron et al. 2019). The high and rapid decomposition of palisade grass after termination occurred because N-stimulated plant growth can be a fresh source of C and N and is associated with increases in microbial biomass and rapid decomposition (El-Sharkawi 2012; Wang et al. 2015). These residues undergo chemical alteration by fungi and bacteria beginning with rapid degradation of cellulose and hemicellulose (Fioretto et al. 2005; Bani et al. 2018). Hence, the slow decomposition rates of dry matter and N release observed in the zero-N application ruzigrass treatment can be explained by the low biomass yield of the cover crop as well as the high C:N ratio of ruzigrass (Rosolem et al. 2017).

Soil NH4 +–N, NO3–N, and total-N content as affected by N application timing on cover crops

The increase of mineral N and total-N content in the soil cultivated with Urochloa spp. were expected because of the N-cycling potential of these species, as shown by the high amounts of dry matter and N accumulation. Our results are congruent with those found by Moro et al. (2013) for mineral N in soil cultivated with cover crops before rice seeding, which observed great NH4+–N and NO3−–N concentrations in soil with palisade grass and ruzigrass but did not study early N fertilizer application on live cover crops or its residues. In our findings, N fertilizer was the responsible source for increasing soil NH4+–N on day of cover crops termination and on day of maize seeding, the time points of N application on the 35 DBS (live cover crops) and 1 DBS (pre-seeding), respectively. Mariano et al. (2015) reported that N fertilization with synthetic and organomineral sources resulted in remarkable increases in NH4+–N and NO3−–N content during the sugarcane growth cycle. Application of N fertilizer usually results in a rapid increase in mineral N availability in the soil solution (Inselsbacher et al. 2014; Mariano et al. 2015), which explains the high availability of mineral N in the soil observed in the present study.

The content of NH4+–N and NO3−–N in the soil solution was directly affected by N fertilizer applied during the growing season (Inselsbacher et al. 2014; Mariano et al. 2015), which increased mineral N available in the soil. However, variations in soil N content also occurred between sampling times due to the cover crop decomposition of biomass between green cover crops in the beginning (0 DAT) and highest N demand of maize (60 DAT), i.e., decomposition of the cover crop residues contributed to provide N to soil. Additionally, cover crops under no-till may influence the potential contribution from SOM mineralization to N release and availability in the soil since SOM and NO3−-N availability tend to be higher by stimulating the microbial activity, especially nitrifying bacteria, in soil under no-tillage system compared to conventional tillage (D’Andréa et al. 2004). Subsequently, mineral N content stabilized 60 days or more after desiccation. This soil N was available for nutrient uptake by the crop, soil microbial processes or N leaching by rain. As in this period there is a high rainfall, a possible potential effect of NO3− leaching may have influenced by weather conditions (Supplementary Fig. 1). Studies have reported depletion of mineral N and subsequent stabilization in tropical soil cultivated with sugarcane (Mariano et al. 2015; Sattolo et al. 2017) that explains the low content of NH4+–N and NO3−–N in the soil at 90 DAT. The cover crop species also recycled N, since the stocks of total-N content in the soil were maintained during the growing season, and N application and the cover crop species were not sufficient to change the total-N content in the soil.

Maize production after early N application and cover crop grown

When soil cultivated with palisade grass received N fertilizer, maize leaf concentration and yield components showed that the plant used N available in the soil for growth and production of grains, contributing with 20–50% to the improvements in the maize response compared to the maize cultivation after palisade grass without N fertilizer. Our study also revealed that the increase of 100-kernel per weight and kernels per ear of maize receiving N fertilizer on live palisade grass (35 DBS) and on its residues (1 DBS), respectively, were similar to those obtained on N applied at conventional method. Nitrogen supply to maize is explained by N application on forage species and thus its biomass mineralization and high N amounts released associated with specific timing of N fertilizer. The early N fertilizer application on palisade grass (35 and 1 DBS) may have provided N to microbial activity and plant decomposition processes and decreased the effect of C:N ratio, inducing in rapid residues decomposition and preventing N from being limiting source for microbial decomposition processes in the soil (Zhou et al. 2017; Bani et al. 2018). These high soil coverage and rapid mineralization of palisade grass combined with early N fertilizer promoted high N uptake during maize growth since the response of crop in succession to cover crops with N fertilizer depends on the forage species and its response to N fertilizer (Schimel and Bennett 2004; Rosolem et al. 2017). Furthermore, the different maize response to biomass mineralization following termination can allow new researches in exploration of N release from cover crops receiving N fertilizer to subsequent cash crop since each crop has a different growth and time of N demand (Landriscini et al. 2019; Silva et al. 2020).

Although our overall data indicate that maize yield components differed among N applications in palisade grass, maize cultivated after palisade grass had the ability to increase grain yields and use N fertilizer regardless of N timing. Indeed, the alternative of early N applications on palisade grass was efficient for enhancing grain yields and, in turn, efficiency of N fertilizer use by maize in the three growing seasons as well as the conventional management. Studies have reported maize grain yield and AE values lower than those observed in the present study (Ciampitti and Vyn 2011; Momesso et al. 2019). The positive effect of mulch mineralization of palisade grass in our findings showed the efficiency in N uptake by cover crop and gradually release of N to maize growth and grain yields. These synchronization between soil N supply and maize demand may occur by microbial decomposition of cover crop residues (Guo et al. 2018; Fan et al. 2019). In contrast, ruzigrass may increase the risk of N losses in the system and may have adverse effects on the subsequent crop since ruzigrass can poorly sync N and the soil N is susceptible to N losses by NO3− leaching and N2O emissions. These results are corroborated by studies of Momesso et al. (2019) and Rocha et al. (2019) that reported low response of yield components, grain yield and AE of maize following ruzigrass.

Maize requires high amounts of N to enhance N uptake and grain yields and proper N fertilizer management is essential to achieve optimal grain yields in an agricultural system. There are no studies reporting success in increasing maize yields via the early application of N to live forage grasses. Our study indicates possible strategies for replacing the conventional sidedressing recommendation in cover crop-maize systems by anticipating application of N fertilizer on palisade grass or its residues. Nitrogen could be applied on live palisade grass before its termination or on its residues just before maize seeding. However, when ruzigrass is introduced in the system, the conventional method of N application is still the best option for increasing maize grain yields and AE. The findings of this study have important implications for increasing food production and nutrient use efficiency in agricultural cropping systems, but more studies are needed to clarify the N dynamics, the microbial processes involved and fate of N fertilizer applied on cover crops or cover crop residues.

Conclusions

Here we showed that early N application is an option as N management strategy on palisade grass as cover crop in the no-till system. The use of palisade grass as a cover crop allows for early N application, is an alternative management to the sidedressing application (conventional method) and proved to be an option for the crop system and environment. In addition to allowing greater flexibility for agricultural operations, early N application on palisade grass improved N agronomic use efficiency similarly to the conventional method. When the cover crop cultivated is ruzigrass, N fertilization must not be applied while the grass is still growing (early N application on live ruzigrass). Beyond crop nutrition, our findings raise questions concerning the N dynamics of cover crops combined with N fertilizer input, the environmental impact of the timing of N fertilization on ruzigrass, and the consequences of N losses for environment and microbial communities in agro-food systems.

Abbreviations

- C:

-

Carbon

- Ca:

-

Calcium

- DAT:

-

Days after termination

- DBS:

-

Days before seeding

- K:

-

Potassium

- Mg:

-

Magnesium

- N:

-

Nitrogen

- NH4 +–N:

-

Ammonium

- NO3 −–N:

-

Nitrate

- P:

-

Phosphorus

- SOM:

-

Soil organic matter

- S:

-

Sulfur

References

Aita C, Giacomini SJ, Hübner AP, Chiapinotto IC, Fries MR (2004) Cover crop mixtures preceding no-till corn: I—Soil nitrogen dynamics. Rev Bras Ciênc Solo 28:739–749. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-06832004000400014

Bani A, Pioli S, Ventura M, Panzacchi P, Borrusa L, Tognetti R, Tonon G, Brusetti L (2018) The role of microbial community in the decomposition of leaf litter and deadwood. Appl Soil Ecol 126:75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2018.02.017

Baptistella JLC, Andrade SAL, Favarin JF, Mazzafera P (2020) Urochloa in tropical agroecosystems. Front Sust Food Syst 4:119. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2020.00119

Borghi E, Crusciol CAC, Nascente AS, Sousa VV, Martins PO, Mateus CC (2013) Sorghum grain yield, forage biomass production and revenue as affected by intercropping time. Eur J Agron 51:130–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2013.08.006

Büchi L, Wendling M, Amossé C, Jeangros B, Charles R (2019) Cover crops with reduced tillage. Field Crop Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2019.107583

Camarotto C, Ferro ND, Piccoli I, Polese R, Furlan L, Chiarini F, Morari F (2018) Conservation agriculture and cover crop practices to regulate water, carbon and nitrogen cycles in the low-lying Venetian plain. CATENA 167:236–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2018.05.006

Cantarella H, van Raij B, Camargo CEO (1997) Cereals. In: van Raij B, Cantarella H., Quaggio, J.A. Furlani AMC (eds) Fertilization and liming recommendation for the state of Sao Paulo (In Portuguese), 2nd edn. Instituto Agronomico, Campinas, pp 43–50 (Boletim Técnico 100)

Cantarella H (2007) Nitrogen. In: R. F. Novais, V. H. Alvarez, N.F. Barros, R.L. Fontes, R.B. Cantarutti, J.C.L. Neves, coodinators, Soil fertility. 1st edn. Sociedade Brasileira de Ciência do Solo, Viçosa, MG. pp 375–470

Castro GSA, Crusciol CAC, Calonego JC, Rosolem CA (2015) Management impacts on soil organic matter of tropical soils. Vadose Zone J 14:1–8. https://doi.org/10.2136/vzj2014.07.0093

Ciampitti IA, Vyn TJ (2011) A comprehensive study of plant density consequences on nitrogen uptake dynamics of maize plants from vegetative to reproductive stages. Field Crop Res 121:2–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2010.10.009

Ciampitti IA, Vyn TJ (2012) Physiological perspectives of changes over time in maize yield dependency on nitrogen uptake and associated nitrogen efficiencies: a review. Field Crops Res 133:48–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2012.03.008

Coleman DC, Callaham Jr MC, Crossley Jr DA (2018) Decomposition and Nutrient Cycling. In: Coleman, D.C., Callaham Jr., M.A., Crossley Jr., D.A. Fundamentals of soil ecology, 3rd edn. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012179726-3/50006-X

Derpsch R, Franzluebbers AJ, Duiker SW et al (2014) Why do we need to standardize no-tillage research? Soil Tillage Res 137:16–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2013.10.002

Dobermann AR (2005) Nitrogen use efficiency: state of the art. Agronomy and Horticulture-Faculty Publications. 316. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/agronomyfacpub/316

El-Sharkawi HM (2012) Effect of nitrogen sources on microbial biomass nitrogen under different soil types. ISRN Soil Sci. https://doi.org/10.5402/2012/310727

Fageria NK, Baligar VC (2005) Enhancing nitrogen use efficiency in crop plants. Adv Agron 88:97–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2113(05)88004-6

Fan F, Yu B, Wang B, George TS, Yi H, Xu D, Li D, Song A (2019) Microbial mechanisms of the contrast residue decomposition and priming effect in soils with different organic and chemical fertilization histories. Soil Bio Biochem 135:213–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2019.05.001

Felismino MF, Pagliarini MS, Valle CB, Resende RM (2012) Meiotic stability in two valuable interspecific hybrids of Brachiaria (Poaceae). Plant Breed 131:402–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0523.2011.01942.x

Fisher M, Rao I, Lascano C (1995) Pasture soils as carbon sink. Nature 376:473. https://doi.org/10.1038/376473a0

Fioretto A, Di Nardo C, Papa S, Fuggi A (2005) Lignin and cellulose degradation and nitrogen dynamics during decomposition of three leaf litter species in a Mediterranean ecosystem. Soil Biol Biochem 37:1083–1091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2004.11.007

Galdos MV, Brown E, Rosolem CA et al (2020) Brachiaria species influence nitrate transport in soil by modifying soil structure with their root system. Sci Rep 10:5072. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61986-0

Gatiboni LC, Coimbra JLM, Denardin RBN, Prado WL (2011) Microbial biomass and soil fauna during the decomposition of cover crops in no-tillage system. Rev Bras Ciênc Solo 35:1051–1057. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-06832011000400008

Guo T, Zhang Q, Ai C, Liang G, He L, Zhou W (2018) Nitrogen enrichment regulates straw decomposition and its associated microbial community in a double-rice cropping system. Sci Rep 8:1847. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20293-5

Habbib H, Verzeaux J, Nivelle E, Roger D, Lacoux J, Catterou M, Hirel B, Dubois F, Tétu T (2016) Conversion to no-till improves maize nitrogen use efficiency in a continuous cover cropping system. PLOS ONE 11:e0164234. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0164234

Inselsbacher E, Oyewole OA, Näsholm T (2014) Early season dynamics of soil nitrogen fluxes in fertilized and unfertilized boreal forests. Soil Biol Biochem 74:167–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.03.012

Jahanzad E, Barker AV, Hashemi M, Eaton T, Sadeghpour A, Weis SA (2016) Nitrogen release dynamics and decomposition of buried and surface cover crop residues. Agron J 108:1735–1741. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2016.01.0001

Keeney DR, Nelson DW (2006) Nitrogen-Inorganic Forms. In: Page AL (ed) Methods of soil analysis, 2nd edn. WI: ASA SSSA, Madison, pp 643–698. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-31211-6_28

Landriscini MR, Galantini JA, Duval ME, Capurro JE (2019) Nitrogen balance in a plant-soil systems under different cover crop-soybean. Appl Soil Ecol 133:124–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2018.10.005

Liu C, Sun X (2013) A review of ecological stoichiometry: basic knowledge and advances. Ref Module Earth Syst Environ Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-409548-9.05519-6

Malavolta E, Vitti GC, Oliveira SA (1997) Avaliação do estado nutricional das plantas: princípios e aplicações, 2nd edn. POTAFOS, Piracicaba (In Portuguese)

Mariano E, Leite JM, Megda MXV, Torres-Dorante L, Trivelin PCO (2015) Influence of nitrogen form supply on soil mineral nitrogen dynamics, nitrogen uptake, and productivity of sugarcane. Agron J 107:641–650. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj14.0422

Momesso L, Crusciol CAC, Soratto RP, Vyn TJ, Tanaka KS, Costa CHM, Ferrari Neto J, Cantarella H (2019) Impacts of nitrogen management on no-till maize production following forage cover crops. Agron J 111:639–649. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2018.03.0201

Momesso L, Crusciol CAC, Soratto RP, Tanaka KS, Costa CHM, Cantarella H, Kuramae EE (2020) Upland rice yield enhanced by early nitrogen fertilization on previous palisade grass. Nutr Cycl Agroecosys. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10705-020-10088-4 ((in Press))

Moro E, Crusciol CAC, Cantarella H, Nascente AS (2013) Upland rice under no-tillage preceded by crops for soil cover and nitrogen fertilization. Rev Bras Cienc Solo 37:1669–1677. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-06832013000600023

Oenema O, Brentrup F, Lammel J, Bascou P, Billen G, Dobermann A, Erisman JW, Garnett T, Hammel M, Haniotis T, Hillier J, Hoxha A, Jensen L, Oleszek W, Pallière C, Powlson D, Quemada M, Schulman M, Sutton MA, Grinsven HJMv, Winiwarter W (2015) Nitrogen Use Efficiency (NUE) - an Indicator for the utilization of nitrogen in agriculture and food systems. Wageningen University, Alterra

Pacheco LP, Leandro WM, de Machado PLOA, Assis RL, Cobucci T, Madari BE, Petter FA (2011) Biomass production and nutrient accumulation and release by cover crops in the off-season. Pesqui Agropec Bras 46:7–25. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-204X2011000100003

Pacheco LP, Barbosa JM, Leandro WM, Machado PLO, Assis RL, Madari BE, Petter F (2013) Nutrient cycling by cover crops and yield of soybean and rice in no-tillage. Pesqu Agropec Bras 48:1228–1236. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-204X2013000900006

Pacheco LP, Monteiro MMS, Petter FA, Nobrega JC, Santos AS (2017) Biomass and nutrient cycling by cover crops in Brazilian cerrado in the State of Piauí. Rev Caatinga 30:13–23. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-21252017v30n102rc

Panison F, Sangoi L, Durli MM, Leolato LS, Coelho AE, Kuneski HF, Liz VO (2019) Timing and splitting of nitrogen side-dress fertilization of early corn hybrids for high grain yield. Rev Bras Cienc Solo 43. https://doi.org/10.1590/18069657rbcs20170338

Paul EA, Clark FE (1989) Soil microbiology and biochemistry. Academic Press, San Diego

Pioneer (2019) Maize hybrid—P3456. Publishing Corteva. http://www.pioneersementes.com.br/milho/central-de-produtos/produtos/p3456. Accessed 17 January 2021

Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, R Core team (2020) nlme: Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R Package Version 3:1–150. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme

R Core Team (2019). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing

Rocha KF, Mariano E, Grassmann CS, Trivelin PCO, Rosolem CA (2019) Fate of 15N fertilizer applied to maize in rotation with tropical forage grasses. Field Crop Res 238:35–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2019.04.018

Rosario-Lebron A, Leslie AW, Yurchak VL, Chen G, Hooks CRR (2019) Can winter cover crop termination practices impact weed suppression, soil moisture, and yield in no-till soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.]? Crop Prot 116:132–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2018.10.020

Rosolem CA, Ritz K, Cantarella H, Galdos MV, Hawkesford MJ, Whalley WR, Mooney SJ (2017) Enhanced plant rooting and crop system management for improved N use efficiency. Adv Agron 146:205–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.agron.2017.07.002

Sattolo TMS, Mariano E, Boschiero BN, Otto R (2017) Soil carbon and nitrogen dynamics as affected by land use change and successive nitrogen fertilization of sugarcane. Agr Ecosyst Environ 247:63–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2017.06.005

Schepers JS, Raun WR (2008) Nitrogen in Agricultural Systems. Agron. Monogr. 49. ASA, CSSA, SSSA, Madison, WI. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronmonogr49.frontmatter

Schimel JP, Bennett J (2004) Nitrogen mineralization: challenges of a changing paradigm. Ecology 85:591–602. https://doi.org/10.1890/03-8002

Silva AO, Ciampitti IA, Slafer GA, Lollato RP (2020) Nitrogen utilization efficiency in wheat: A global perspective. Eur J Agron 114:126008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2020.126008

Soares JR, Cassman NA, Kielak AM, Pijl A, Carmo JB, Lourenço KS, Laanbroek HJ, Cantarella H, Kuramae EE (2016) Nitrous oxide emission related to ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and mitigation options from N fertilization in a tropical soil. Sci Rep 6:30349. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30349

Soil Survey Staff (2014) Keys to soil taxonomy, 12th edn. USDA-NRCS, Washington, DC

Soratto RP (2011) Nitrogen early application and sources for common bean in succession to forage grasses in no-tillage system. Thesis, Sao Paulo University

Tanaka KS, Crusciol CAC, Soratto RP, Momesso L, Costa CHM, Fransluebbers AJ, Oliveira Junior A, Calonego JC (2019) Nutrients released by Urochloa cover crops prior to soybean. Nutr Cycl Agroecosys 113:267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10705-019-09980-5

Turmel MS, Speratti A, Baudron F, Verhulst N, Govaerts B (2015) Crop residue management and soil health: a systems analysis. Agr Syst 134:6–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2014.05.009

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) (2019) USDA agricultural projections to 2028

Wang H, Boutton TW, Xu W, Hu G, Jiang P, Bai E (2015) Quality of fresh organic matter affects priming of soil organic matter and substrate utilization patterns of microbes. Sci Rep-UK 5:10102. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep10102

Worldometers (2019) Available online at: http://www.worldometers.info/worldpopulation/world-population-projections/ (Accessed February 20, 2019)

Zhou Z, Wang C, Zheng M, Jiang L, Luo Y (2017) Patterns and mechanisms of responses by soil microbial communities to nitrogen addition. Soil Biol Biochem 115:433–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.09.015

Acknowledgements

LM received a scholarship from CAPES – Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Level Personnel [Finance Code 001 and Grant No. PDSE 88881.187743/2018-01]. CACN was supported by scholarship from the FAPESP – São Paulo Research Foundation [Grant No. 2016/12317-7]. This work was undertaken as part of NUCLEUS, a virtual joint center to deliver enhanced N—use efficiency via an integrated soil—plant systems approach for the United Kingdom and Brazil. Funded in the United Kingdom by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council [Grant No. BB/N013201/1] under the Newton Fund scheme; and in Brazil by FAPESP [Grant No. 2015/50305–8]; FAPEG–Goiás Research Foundation [Grant No. 2015–10267001479]; and FAPEMA–Maranhão Research Foundation [Grant No. RCUK–02771/16]. The authors would like to acknowledge the FAPESP [Grant No. 2015/17953-6] for partial financing and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for awards for excellence in research to CACC, RPS, CAR, and HC. This publication is publication number 7206 of the Netherlands Institute of Ecology (NIOO-KNAW).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Momesso, L., Crusciol, C.A.C., Soratto, R.P. et al. Early nitrogen supply as an alternative management for a cover crop-maize sequence under a no-till system. Nutr Cycl Agroecosyst 121, 1–14 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10705-021-10158-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10705-021-10158-1