Possibly, the only metaphysical hypothesis that is needed by physics is, as Dirac used to say at the beginning of his lectures, that there exists an external world.

-Dorato (2010, p. 2)

Abstract

Scientific realism is usually presented as if metaphysical realism (i.e. the thesis that there is a structured mind-independent external world) were one of its essential parts. This paper aims to examine how weak the metaphysical commitments endorsed by scientific realists could be. I will argue that scientific realism could be stated without accepting any form of metaphysical realism. Such a conclusion does not go as far as to try to combine scientific realism with metaphysical antirealism. Instead, it amounts to the combination of the former with a weaker view, called quietism, which is agnostic on the existence of mind-independent structures. In Sect. 2, I will argue that the minimal claim that brings together every scientific realist view is devoid of any metaphysical commitment. In Sect. 3, I will define metaphysical realism and antirealism. Such work will be instrumental in providing a more precise statement of quietism. Finally (Sect. 4), I will argue that assuming quietism, it is still possible to make sense of the debate between scientific realists and antirealists.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The debate on the ontological status of unobservable theoretical entities (i.e. entities posited by our best scientific theories that human beings cannot observe directly) is a central topic in philosophy of science. Even today, the question of their existence splits into two main camps the philosophers of science involved. On the one hand, there are the so-called scientific realists, who claim that unobservable entities, as posited by our best scientific theories, exist. Therefore, these scientific theories are, given a correspondence theory of truth, (at least approximately) true. On the other hand, the scientific antirealists hold that scientific theories are either false, without a truth value at all or cannot be put into correspondence with the world, and thus it makes no sense to talk about their truth-value.Footnote 1 Both ‘scientific realism’ and ‘scientific antirealism’ are umbrella terms for a wide range of positions that differ massively from each other; therefore, as in other similar cases, general discourses incur the risk of missing crucial details.Footnote 2 Given the generality of the argument here presented, we will take such a hazard with the proviso that some conclusions cannot be generalized to every form of scientific (anti-)realism.

To a high degree of generality, every view that claims that some entities a, b and c of the same kind objectively exist is considered a ‘realist’ position. Antirealist positions, on the contrary, claim the opposite. For instance, they claim that those entities do not exist, or they argue that their existence is mind-dependent, or that it depends on natural languages, human beings’ epistemic status, and so on.Footnote 3 realism and antirealism are attitudes that can be held on a wide variety of debates. Since these debates concern different kinds of entities, it should not be surprising that realist positions are mostly independent of each other. Being a realist on moral values, say, does not commit one to be a realist also on mathematical entities.

As the debate between scientific realism and antirealism is usually presented, it is reasonable to think that it is orthogonal to the discussion on the existence of a mind-independent reality (i.e. the thesis of metaphysical realism). Admittedly, there are secure connections between these two forms of realism; nonetheless, as the theses are usually stated, they seem (at least) logically independent.Footnote 4 In other words, it should be possible in principle to hold any combination of scientific and metaphysical realism and antirealism. Indeed, even what is considered the most counter-intuitive combination of the four, namely scientific realism plus metaphysical antirealism, has found some advocates in the past.Footnote 5 At the same time, it is also natural to think that some combinations are more attractive than others. For instance, one who holds a strong form of scientific realism will more naturally be inclined to accept metaphysical realism rather than some kind of idealism. In order to strengthen the claim that scientific propositions are true, one may want to insist that such a truth must be understood as correspondence with some underlying reality.

Be that as it may, such logical independence between metaphysical and scientific realism seems, in contemporary literature, not to be acknowledged anymore. Throughout the literature, standard presentations of scientific realism describe the theory as if one of its essential components were metaphysical realism (Psillos 1999; Chakravartty 2017; Wright 2018).

In what follows, the question I want to deal with is to what extent scientific realists can weaken their metaphysical commitment. I argue that scientific realism can be stated without any metaphysical commitment: it is possible to be a scientific realist without accepting neither metaphysical realism nor antirealism. To do so, I firstly (Sect. 2) outline what I take to be the minimal claim of scientific realism, i.e. the thesis shared by all forms of scientific realism—the least common denominator, so to speak, of these views. I then (Sect. 3) characterize both metaphysical realism and antirealism before introducing a third view, namely ‘quietism’, which is a position neutral on the debate over the existence of a mind-independent reality. Finally (Sect. 4), I show that holding metaphysical quietism, the disagreement between scientific realist and antirealist is still genuine. I dub this version of scientific realism, devoid of any metaphysical commitment, ‘Quiet Scientific Realism’. I claim that its coherence is enough for showing that scientific realists could avoid any metaphysical commitment, without defending the view over other variants of scientific realism. Proving that some apparently necessary commitments of a position are not essential is a noteworthy achievement by itself. Even in the case, as it is with scientific realism, in which the majority of its advocates spontaneously endorse the commitments above. Finally, such a question should interest those philosophers that, albeit intuitively inclined toward realism, are moved by arguments in favour of scientific antirealism. Indeed, scientific realism, as it is commonly stated, hinges on views that are far from being uncontroversial. As a paradigmatic example, consider the notion of truth as correspondence and the belief that we can know whether our languages—be they natural or formal—carve Nature at its joints.

2 The Entangled State of Scientific and Metaphysical Realism

The question of whether a scientific realist is committed to metaphysical realism should be rather trivial. If the two theses are logically independent, then one can certainly be a realist about unobservable entities without any commitment to a mind-independent external world. Nonetheless, recent literature seems to ignore the independence above: scientific realism, indeed, is usually presented with a robust metaphysical component. If metaphysical realism were a necessary part of scientific realism, then it would be impossible, by definition, to be a scientific realist without any commitment to some strong version of metaphysical realism. For instance, according to the now-standard definition proposed by Psillos, scientific realism is a threefold thesis: it has a metaphysical, a semantic and an epistemological component. The first one is a clear commitment to a mind-independent structured world:

The metaphysical thesis: The world has a definite and mind-independent structure. (Psillos 2005, p. 688).

If one thinks that “scientific realism” is a label that we can use freely, as long as we define its meaning, then it might seem that the question I am addressing here is more semantical than substantial, if substantial at all. If Psillos’ presentation of scientific realism were just a definition, this paper should end here with a negative answer to its hypothesis. However, the issue is that “scientific realism” is an umbrella term; such a fact is so widespread that when one says “I am a scientific realist” the usual reply he/she gets is “of which kind?” Defining “scientific realism” then is not just a matter of choosing an arbitrary meaning. Rather, it consists in finding the least common denominator, say, between all the views that share, at their heart, the same intuition about the scientific practice; to distil, so to speak, the minimal claim from which all the scientific realist variants want to start for building their view.

Alas, as it is with standard definitions of scientific realism, the realists’ minimal claim is also commonly stated with a metaphysical component. Massimi (2018, pp. 4–5) for example, argues that the minimal thesis of scientific realism is the normative claim that (our best) scientific theories ought to map “onto nature in a truthful way, in the simple-minded sense of making our scientific knowledge claims correspond to perspective-independent states of affairs that can adjudicate their truth or falsity”.

I will argue instead that the metaphysical thesis should not survive this process of ‘distillation’: the minimal claim should not hinge on any metaphysical component. Three main facts motivate such a claim.

The first has been already pointed out, namely, that many contemporary scientific realists want to commit themselves to metaphysical realism to strengthen their claims. Therefore, it is quite natural that in their definitions of scientific realism, they include a metaphysical commitment. For instance, Devitt (1991) posits that metaphysical realism should be considered central to scientific realism. Nevertheless, such a fact is not per se enough for establishing that they are necessarily committed to such a thesis. Some authors argued that metaphysical realism is necessary for any meaningful defence of scientific realism. The most notable argument of this kind is due to Psillos (1999, ch. 3). Psillos criticizes Carnap’s neutral view and claims that the failure of Carnap’s neutralism established that metaphysical realism is necessary “to any meaningful defence of scientific realism” (Psillos 1999, p. xviii). However, Psillos’ criticisms against those views that are neutral between scientific realism and antirealism do not apply to the present work. Firstly, even if it is admitted that Psillos successfully managed to show that Carnap’s view is incoherent, it does not follow that neutral positions are incoherent per se, nor that a form of metaphysical realism is necessary. Secondly, Psillos’ argument relies on the assumption that the only alternative to metaphysical realism is antirealism; yet, showing that there is a third possibility is exactly one of the points made in this paper. Finally, Psillos’ criticism about the possibility of views that attempt to stay neutral on the debate between scientific realism and antirealism hardly apply to the work presented in this paper. Even though I agree that those kinds of view are hardly defensible, the central point of this paper is to present a form of scientific realism that is neutral on the metaphysical level, rather than being neutral on the existence of scientific entities. The question I am concerned with is whether scientific realists can avoid a metaphysical commitment, rather than arguing that they should. Therefore, I will not argue that scientific realists should not posit metaphysical realism as a cornerstone of their views. I will argue, instead, that it is possible to hold a weaker form of scientific realism that avoids any strong commitments to metaphysical reality.Footnote 6

The second reason is that these presentations of scientific realism are historically contingent. On the one hand, the forms of metaphysical antirealism debated in the modern (and previous) philosophical literature are, in our light, “beyond the pale of serious possibility” (Rosen 1994, p. 277). On the other hand, views that combine metaphysical antirealism and scientific realism, such as those in a Kantian or Neo-positivists spirit, are nowadays quite old-fashioned. The reason being their (alleged) scarce coherence and the suspicion mentioned above that metaphysical antirealism raises nowadays.Footnote 7 Such a fact seems to have convinced the majority that scientific realism is incompatible with metaphysical antirealism. However, to conclude from the incompatibility with metaphysical antirealism that scientific realism is then committed to metaphysical realism is too hasty. Indeed, as we will see, the denial of the antirealism does not amount to an acceptance of realism.

Finally, no aspect of the debate on scientific realism hinges on the metaphysical component: modern antirealists challenge only the semantical and the epistemic components of scientific realism. Such a fact, by itself alone, certainly does not prove anything. Nevertheless, if the whole disagreement between realists and antirealists can make sense without any reference to the metaphysical component, then one may argue that both scientific realism and metaphysical realism are, in fact, independent. I think it is so. Consider the following thought experiment:

Let us suppose that Alice is a solipsist, i.e. she holds the view that she is the only real entity, and external reality is entirely the product of her mental activity. Alice notices that her reality presents many regularities. Moreover, she notices that some of her ideas (called ‘scientists’) study these regularities and claim that they are due to the existence of unobservable entities. Alice believes the scientists’ claims and thinks that (at least some of) these unobservable entities exist, in the sense that they are as real as her other ideas (like her idea of tables, chairs and the scientists themselves). Therefore, she has a strong disagreement with Bob, who think that scientific theories allow us only to make accurate predictions. According to Bob, indeed, we are rationally justified in believing only in those entities that human beings can observe directly.

Why does Alice think that unobservable scientific entities exist (in the same sense in which she would say that table, chairs and so on exist)? Well, Alice argues that scientists’ predictions are really accurate. For instance, they can predict how sophisticated machinery, such as laptops, would work under specific conditions; for example, they predict what would happen if I press some combination of buttons on such a device. Moreover, they explain what is happening in the laptop (partially) in terms of electricity, that is supposed to be the movement of some tiny unobservable particles called ‘electrons’. Without electrons, the functioning of the laptop would be a miracle. Therefore, she concludes, in the same way in which we admit the laptop’s existence, we should believe in electrons.Footnote 8

According to Alice though, neither the electrons nor the laptops exist in a metaphysically loaded sense, i.e. as a part of a mind-independent reality. Is she a scientific antirealist? It is not that clear. Indeed, even though she strongly supports metaphysical antirealism, she can disagree both with empiricists, who do not want to commit themselves to the existence of unobservable entities and with instrumentalists, who claim that the scientists’ speaking of electrons must not be taken literally. Since scientific realism is usually presented with a metaphysical component, arguments in favour of the former are taken to support also metaphysical realism. As the thought experiment presented is meant to show, such a conclusion is too hasty.

I take these reasons to be enough for concluding that the minimal claim that scientific realists must hold, to be considered realist in the first place, should not involve any metaphysical commitment. Consider the case of everyday life, where human beings naturally speak of what they experience; moreover, quite naturally, we form a picture of what the world is like, assigning a name to what we take to be objects. Still, accepting such a fact does not commit to any metaphysical commitment, i.e. that such objects exist as we perceive them, in a mind-independent external world. Uttering ‘there is a table in front of me’, say, is not a philosophical thesis in is own right but a commonsense discourse. Therefore, the minimal claim that scientific realists could hold is that existential statements involving unobservable entities posited by our best scientific theories are true in the same sense in which ‘there is a table in front of me’ could be. Therefore, the minimal claim (henceforth ‘MC’) that characterizes a scientific realist, in contrast to an antirealist, should be something along the following lines:

- (MC):

-

Unobservable entities posited by our best scientific theories are at least as real as everyday entities.

Such a claim provides the idea that we, qua human beings, are naturally inclined to build a naive picture of the world starting from the experience of what surrounds us, and such a picture of nature is improved and enriched by scientific inquiry. The scientific and the naive view of the world are not in contrast, but part and parcel of the same picture.Footnote 9 It is easy to misunderstand such a claim. Of course, scientific statements may contradict what naïvely we think is the case judging from our experience. Indeed, scientific discoveries often are, in this sense, revisionary. However, note firstly that scientific theories must also explain why what we perceive is not as such. Otherwise, their trustworthiness could reasonably be questioned. Secondly, what I meant is that the scientific description does not concern a different world from the one we observe empirically in everyday experience. There are not two different realities: the real one investigated by science and the illusory plane of our everyday life.Footnote 10 In other words, (MC) provides the idea that sentences like ‘x exists’ or ‘x is real’ have at least the same meaning when x is either an everyday or a scientific entity.Footnote 11 However, the claim is minimal because it allows an understanding of such a reality just in empirical terms, without being committed in “the illusory, the fictitious, and the purely conceptual” (Feigl 1943, p. 386) sense that metaphysical realists attach to ‘reality’ and ‘existence.’

2.1 The Natural Ontological Attitude

The minimal claim (MC) proposed is not entirely new. Indeed, the idea that scientific entities are at least metaphysically on par with everyday objects can be found here and there in the literature. The same spirit seems to be shared, for example, by Rescher (2010, p. 86), when he argues that “science and common life [...] neither deal with different realms of being, nor yet is one of them reality-oriented and the other mere illusion. In ordinary life and science we emphatically do not address different realities or different modes of being”. What argued in the last section is also close to the view defended by McMullin (1984, p. 24):

Recall that the original motivation for the doctrine of scientific realism was not a perverse philosopher’s desire to inquire into the unknowable or to show that only the scientist’s entities are “really real”. It was a response to the challenges of fictionalism and instrumentalism, which over and over again in the history of science asserted that the entities of the scientists are fictional, that they do not exist in the everyday sense in which chairs and goldfish do.

Among all the authors that proposed such a correspondence between everyday life and science, one approach is so strikingly similar to mine that it deserves a brief discussion.

Arthur Fine (1984a, b, 1986) proposed a view, dubbed ‘the natural ontological attitude’ (henceforth ‘NOA’), supposed to stand in between scientific realism and antirealism. Indeed, he argues at length that the arguments in favour of both scientific realism and antirealism are not compelling. As a contrast to the philosophical theses that these views maintain, Fine describes the core of NOA as an attempt of letting science speak for itself. Indeed, the only positive claim that NOAers have to endorse is what he dubs the ‘homely line’: we have to ‘accept scientific results in the same way we accept the evidence of our senses’ (Fine 1984b, p. 96). NOA is, according to Fine, not a realist nor an antirealist view. Instead, it consists of an attempt to avoid interpreting scientific practice philosophically.

The similarity between the ‘homely line’ and (MC) seems striking. Indeed, it seems straightforward to grant that if we have to accept scientific results as we accept everyday truths, then scientific entities must have the same metaphysical status as everyday objects, whatever such a metaphysical status may be. If Fine’s homely line and MC are so similar, and (MC) is a sufficient condition for scientific realism, it would follow that NOA is not somewhere in between realism and antirealism. Indeed, it would count as a realist view.Footnote 12 Why does Fine refuse to call NOA a realist position then? I think that it is so because he is convinced that scientific realism is committed to some form of metaphysical realism; as a matter of fact, the acceptance of this thesis is the only feature of scientific realism that he criticizes at length. His prose is quite clear on this point:

What then of the realist, what does he add to his core acceptance of the results of science as really true? [...] what the realist adds on is a desk-thumping, foot-stamping shout of “Really!” So, when the realist and antirealist agree, say, that there really are electrons [...] what the realist wants to add is the emphasis that all this is really so. “There really are electrons, really!”. (Fine 1984b)

For realism, science is about something; something out there, ‘external’ and (largely) independent of us. The traditional conjunction of externality and independence leads to the realist picture of an objective, external world; what I shall call the World. According to realism, science is about that. (Fine 1986, p. 150)

To sum up, Fine’s intention of crafting a neutral position on the debate on scientific realism is motivated by two main reasons: (i) an empiricist-influenced suspicious attitude towards the metaphysical commitment to a mind-independent external world and (ii) a decision to distance himself from contemporaneous scientific realists that endorsed such a commitment. Still, Fine refuses, precisely because the core of NOA consists of refusing to add any philosophical commitment to the scientific enquiry, to give any positive claim to replace metaphysical realism. His satirical depiction of the belief in a mind-independent external world (which he dubs the ‘World’) is not backed up with any positive claim about how we are to understand terms like ‘existence’ and ‘reality’.

Be that as it may, it is not my intention, against Fine’s will, to add to NOA any philosophical commitment nor to insist that NOA is a form of scientific realism. In contrast, in what follows I will argue that it is possible to build a coherent form of scientific realism that, retaining (MC) and sharing the intuition that lies at the heart of NOA, is devoid of any metaphysical commitment (Sect. 5). Such work should be enough for showing that scientific realists are not necessarily committed to metaphysical realism. To do so, one has to clarify what refusing to accept any metaphysical commitment means. The next section is devoted to this topic.

3 The Collapse of Metaphysical Realism

Where Fine’s NOA was supposed to be a form of ’scientific quietism’,Footnote 13 our aim here is to make sense of a form of scientific realism without commitments to a metaphysically loaded reality, in other words, to assess the tenability of the combination of scientific realism with metaphysical quietism. To do so, I present in (Sect. 3.1) the core intuitions on which metaphysical realism and antirealism hinge. Then in (Sect. 3.2) I present what I take to be a more precise way of defining metaphysical realism and antirealism. The work done in these sections I then use in Sect. 3.3 to present a form of metaphysical quietism, one that is partially inspired to Neo-Positivists’ attitude toward metaphysics.

3.1 A Rough Picture of Metaphysical Realism and Antirealism

Like scientific (anti-)realism, ‘metaphysical (anti-)realism’ is an umbrella term for a wide range of views that slightly differ from each other. Generally speaking, we can characterize metaphysical realism as the view according to which there exists an external reality (what Fine calls the ‘World’); ‘external’ means that such a reality is strongly independent of the human mind. I take the common intuition that lies underneath metaphysical realism to be that the World existed, exists and will exist, independently of the presence of human beings; part and parcel of metaphysical realism is also the thesis that the world itself has a determinate structure. Finally, metaphysical realists usually also hold an epistemic claim according to which human beings can have access (at least partially) to such a structure. Metaphysical antirealism amounts to the negation of metaphysical realism. On epistemic or metaphysical grounds, metaphysical antirealists challenge either the existence or the mind-independence of such a World, or both.Footnote 14

Generally speaking, debates over the reality of some entities a, b and c of the same kind hinge on two theses:Footnote 15

-

(i)

a, b and c exist.

-

(ii)

a, b and c are mind-independent.

Realist positions about a, b and c will hold the conjunction of (i) and (ii). Moreover, they will usually add some epistemic claims, i.e. that we can know that (i) and (ii). In contrast, antirealist views will deny either (i) or (ii) (or both), usually denying also some epistemic access to the truth value of these statements.

Along these lines, we can flesh out the core commitments of metaphysical realism and antirealism. Consider the following claims:

-

(1)

There exists a mind-independent external world (i.e. the World).

-

(2)

The World has a definite mind-independent structure.

-

(3)

We can know that (1).

-

(4)

We can know that (2).

-

(5)

We can know that (2) and we have access to (at least part of) the Worlds’s mind-independent structure.

All metaphysical realists accept at least the conjunction of (1) and (2). The greater the number of epistemic claims held (from among (3), (4) and (5)), the stronger the metaphysical realism will be. Metaphysical antirealists, on the other hand, would endorse the negation of (1) or (2), with stronger versions denying both; moreover, metaphysical antirealists would usually deny at least one epistemic claim from among (3)–(5).

3.2 Lost in the Plurality of Worlds

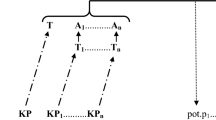

I will propose now a way to characterize metaphysical realism and antirealism inspired by Chalmers (2009). Such a work will be instrumental in providing a clear definition of metaphysical (anti-)realism and, in turn, of quietism. The core idea is to propose Carnap’s (1950) framework in the most theory-neutral and intuitively clear way.Footnote 16 Let us call a class of singular terms in an idealized language a ‘domain’ (\({\mathfrak {D}}\)). Given any language, the domain is an exhaustive list of all the terms that refer to some entities ( or state of affairs, facts, objects, what have you). We will call furnishing function a map from worlds to domains, so that ‘such a map specifies a class of entities that are taken to exist in that world’ (Chalmers 2009, p. 108). Each furnishing function then creates ordered pairs of world and domain (\(\langle w _{n}, {\mathfrak {D}}_{n}\rangle\)), that we will call furnished worlds. Now, we can

postulate that for any ordinary utterance, the context of utterance determines a furnishing function. Intuitively, this function corresponds to the ontological framework endorsed by the speaker in making the utterance. For example, ordinary discourse about tables and chairs may involve a context that determines a commonsense furnishing function. Typical mathematical discourse may involve a context that determines a furnishing function that admits all sorts of abstract objects, and so on. If we make the standard assumption that for every utterance there is a world of utterance, then the world of utterance combined with the furnishing function of the context of utterance will together determine a domain. It is this domain that will be used to assess the truth of the utterance (Chalmers 2009, p. 108).

An existential claim (such as ‘there is a laptop’) will be true if the entity involved in the statement (‘the laptop’ in the example) is a member of the domain of the furnished world picked by the furnishing function, the latter being determined in turn by the context of utterance. In other words, when an existential claim is uttered, the context will determine a furnished world. A furnished world is simply a named list of entities. If we are in a math class, for example, the furnished world will contain abstract objects such as numbers, functions, and so forth. If we are instead, in a pub, the furnished world will contain what is naively taken to exist (other people, glasses, money and so on). An existential claim is true if the entity involved in the sentence is a member of the furnished world picked by the context; it is false if the entity is not a member of such a furnished world. The machinery thus introduced is useful for defining metaphysical realism. We can distinguish (at least) three broad kinds of metaphysical realism:

- (HMR):

-

Hardcore Metaphysical Realism There is a context of utterance that directly picks, as if it were a furnished world, the external mind-independent World itself.

- (OMR):

-

Ontologese-based Metaphysical Realism There is only a furnished world that can be mapped to the external mind-independent world.

- (SMR):

-

Sophisticated Metaphysical Realism There is a class of isomorphic furnished worlds that can be mapped to the external mind-independent world.

According to (HMR), an existential claim can have two readings: it can quantify (i) over a furnished world, as when we say that ‘numbers exist’ during a math course, or (ii) it can be unrestricted, i.e. the domain is the world itself. In the second, metaphysically loaded sense, existential claims are not restricted to any domain: their truth-value is evaluated directly through a comparison with the world itself. The view entails the existence of an ‘unrestricted quantifier’ ranging over all the entities that exist in the World. Such a view is defended mostly, as far as I know, by some contemporary analytic metaphysicians.Footnote 17

(OMR) is far weaker than (HMR). The former accepts, indeed, that every existential claim is restricted to some domain. At the same time, though, it claims that there is a domain that genuinely reflects how the world is, that ‘carves Nature at its joints’ (Sider 2011). When we are in a math course, the context determines a furnished world full of abstract objects, whereas when we are doing metaphysics, the context determines a different furnished world. Nevertheless, according to (OMR), the latter is privileged: it is indeed the only furnished world that describes the mind-independent external world. Such a view amounts to the claim that metaphysical/ontological discourses are spoken in a proper language rather than the natural one. The language of ‘the metaphysics room’ has been dubbed by Sider (2009) ‘Ontologese’. (OMR) seems to be either implicitly endorsed or explicitly defended by many contemporary analytic metaphysicians.Footnote 18

Finally, (SMR) is a weaker form of metaphysical realism according to which there is a furnished world that describes the external World correctly, but it is not unique. Instead, there is a set of equivalent furnished worlds that describes reality. Some metaphysical realists, with a deflationary attitude toward the majority of the questions debated in analytic metaphysics, defend such a view. Consider, as an example, the debate that opposes four-dimensionalism (Sider 2001) and three-dimensionalism (Fine 2008). Friends of (SMR) might argue that the debate is unsubstantial: insofar as the claims made by one view can be consistently mapped in claims made by the opposing theory and vice-versa, these theories are equivalent. That is to say that there is not a true theory and a false one. They are both ‘true’, in the sense that they are a conceptually different but metaphysically equivalent way of cutting reality.Footnote 19 According to the friends of (SMR) then, there is not one true description of the world;Footnote 20 rather, there are many equivalent ways of describing it. The mind-independent structure of the World can then be inferred from the invariant features of these descriptions.Footnote 21

The three-sided categorization I have proposed is certainly not exhaustive. Indeed, it is easy to find other possible variants of metaphysical realism.Footnote 22 At the same time, it is general enough to cover the views most discussed in the literature. What these three views have in common is the possibility of defining a new concept, i.e. that of ‘being REALLY true’. Now we can say that an existential statement is REALLY true (or equivalently, an entity REALLY exists) if the entity involved in the claim is

- RT\(_{\mathbf {(HMR)}}\):

-

part of the external world and the existential statement quantifier is unrestricted.

- RT\(_{\mathbf {(OMR)}}\):

-

a member of the furnished world that can be mapped to the World.

- RT\(_{\mathbf {(SMR)}}\):

-

a member of a furnished world that can be mapped to the World.

The definition of these predicates is quite helpful. Indeed, metaphysical realists (of any kind), may be open to the idea that, in a certain sense, when you are in a math course, it is true that numbers exist. Notwithstanding, they want to differentiate such a non-metaphysical way of talking of existence from a metaphysically loaded one. The predicates introduced successfully deliver such a distinction: where abstract entities exist as part of a domain on which we quantify in a particular context, they do not REALLY exist, as tables, chairs or whatever is taken to REALLY exist, do.Footnote 23

As with metaphysical realism, the machinery of the furnishing function is useful for differentiating the various forms of metaphysical antirealism as well. There is no need to do it at length. Metaphysical antirealisms can be divided into kinds depending on which of the realists’ claims are rejected. Therefore, metaphysical antirealists’ main claim may amount to the negation of metaphysical realism on metaphysical (i.e. there is no World), epistemic (i.e. we do not have any access to the World) or semantic (negating correspondence view on truth) grounds.

The distinctions I introduced will play no active role in what follows. At the same time though, they are far from irrelevant for our discussion. These distinctions show that ‘metaphysical realism’ is not a uniform and unproblematic thesis, but a family of substantially different views. Moreover, they show that scientific realists have to specify which form of scientific realism is part of their theses and that choosing different forms of metaphysical realism can give life to different kinds of scientific realism. Hence, metaphysical realism is not an unproblematic assumption that can be endorsed without further specification: saying that metaphysical realism is part of scientific realism is not very illuminating until it is specified which kind of metaphysical realism is endorsed.Footnote 24 Finally, the metaphysical commitment is not as innocent as many scientific realists think it is. Usually, when scientific realists think about metaphysical realism they have in mind some view in the vicinity of (HMR). Note that (arguably) such a view is really at odds with some scientific theories. Just to make a quick example, robust metaphysical realism cannot be reconciled with some lively debated interpretations of quantum mechanics.Footnote 25 Surely, metaphysical realists could answer such a challenge in many ways, e.g. by adopting a different interpretation of quantum mechanics. But such a fact does not diminish the strength of the point I want to drive home here, namely, that assuming metaphysical realism as an assumption is not so clear and unproblematic as it is commonly presented.

3.3 The Lost World

Rejecting (anti-)realism does not amount to accepting its alternative.Footnote 26 Even if it is not as discussed as its rivals, a third view, dubbed ‘quietism’, has been proposed in the literature. The core tenet of quietism is that as there are no convincing reasons for siding with antirealists, there are no reasons either for being realists. We can distinguish three forms of quietism, based on the motivations held for being neutral on the debate:

- (DMQ):

-

Deflationary Metaphysical Quietism: The debate between metaphysical realists and antirealists is meaningless. Indeed, claims (1) and (2) do not have any meaning at all.

- (SMQ):

-

Semantic Metaphysical Quietism: The debate between metaphysical realists and antirealists is unsubstantial: there is no way to establish what is the precise meaning of claims (1) and (2) (albeit they have one).

- (EMQ):

-

Epistemic Metaphysical Quietism: The debate between metaphysical realists and antirealists cannot be settled. Indeed, the epistemic status of human beings is such that the truth of either (1) or (2) (or both) is precluded. Therefore either (3) or (4) (or both) are false.

What all these views share is the belief that, insofar as the question upon which the debate hinges on cannot have a definite answer, we are not rationally entitled to take a stance on the debate, no matter how intuitive or useful assuming such a view might be.

The first two forms of quietism, (DMQ) and (SMQ), have already been advocated by some philosophers in the past. For instance, they seem close to what McDowell (1994) argues. Rosen (1994, pp. 279–280) nicely articulates the idea that the question of metaphysical realism is not semantically well-formed:

We sense that there is a heady metaphysical thesis at stake in these debates over realism - a question on par with the issues Kant first raised about the status of nature. But after a point, when every attempt to say just what the issue is has come up empty, we have no real choice but to conclude that despite all the wonderful, suggestive imagery, there is ultimately nothing in the neighbourhood to discuss.[...]

If it makes no good sense to deny the realist’s characteristic claims, then it makes no good sense to affirm them either. Quietism, as the view is sometimes called, is not a species of realism. It is rather a rejection of the question to which ‘realism’ was supposed to be the answer.

In what follows, I will assume (EMQ). The core thesis of this form of quietism is that the question on which realism and antirealism debate cannot in principle be settled. In other words, even granting that both (1) and (2) have a precise meaning, our epistemic status is such that we will never be able to reach the knowledge needed for establishing whether these claims or their negation are true. Claiming that (1) cannot be known may seem to amount to raising the white flag in front of radical scepticism, i.e. the view according to which all the content of our experience is misleading. ‘Such a global failure would result if we were to be ‘brains-in-a-vat’, our brains manipulated by mad scientists (or computer programmes, as in the movie The Matrix) so as to dream of an external world that we mistake for reality’ (Khlentzos 2016).Footnote 27 Even if I concede that we cannot know with certainty whether we are in a kind of collective hallucination or the like, I am not moved by these scenarios either. And this is so because there are no positive reasons to believe that what we experience is not somehow grounded in a mind-independent external world in the first place. In other words, albeit the radical sceptical scenarios cannot be ruled out with certainty, at the same time, there are no motivations for taking them in serious consideration to begin with. No evidence in our experience suggests that there is nothing behind it rather than something. According to my version of (EMQ) then, (1) can be assumed unproblematically as a working assumption. What I am more sceptical about instead is the possibility of establishing the truth of (2). The impossibility of knowing whether (2) is true, implies rejecting (4). The idea is that we have many different ways of describing reality, but we cannot know whether they capture what the structure of the World actually is. At the end of the day, it all boils down to what conception one has of metaphysical statements. According to metaphysical realists, a metaphysical statement such as “that rose instantiates the property of being red” is understood as the only true way of talking about the world: a rose is an object detached from the rest of the world, and it really has the property of being red. According to metaphysical antirealists, however, claims like the one above concern mind-dependent entities. It is us, qua human beings, that extrapolate the rose from the rest of our perception and we conceptualize it, say, in terms of properties instantiated. But neither the rose nor its properties are part of the external world. Epistemic quietists refuse both the realist and the antirealist understanding of metaphysical statements. While friends of (EMQ) reckon that metaphysical statements are part of our best way of describing our experience, they are agnostic about whether such a description actually corresponds with reality itself, as the metaphysical realists contend, or if it is just a personal or collective illusion in which our consciousness is trapped, as solipsists and transcendental idealists argue. Friends of (EMQ) claim that it is simply impossible to know if our descriptions capture (or not) how reality is structured in itself. In the quietists’ eyes, all metaphysical debates are concerned with what is the best description of the entire reality that is available to us at the moment. Each philosopher has his/her own, usually incomplete, preferred description of reality. Concerning properties, for instance, some philosophers hold that a universal property is instantiated by many entities, while others claim that each entity instantiates a different property from the ones instantiated by other entities, no matter how similar these properties may look. According to the quietists, the debate between universalists and trope theorists, to stick to the example above, amounts to what conception of properties is part of our best description of reality. Quietists are happy to engage in metaphysical discussions by defending particular views against others. Still, if asked whether they think that reality is like it is pictured by the views defended, the quietists answer with a humble “that is the best description of reality we have so far.” According to quietists then, there is a preferred description of reality: a description of the whole reality that human beings have been trying to build from ancient times through scientific and philosophical investigations of experience.Footnote 28 The issue is that philosophers (and scientists alike) disagree about what such a privileged description must amount to.

To clarify such an idea, the machinery of furnished function previously introduced comes in handy. The core claim of (EMQ), as here presented, is that existential claims are evaluated as introduced in (Sect. 3.2): the context in which a statement is uttered determines, through a furnishing function, a particular domain; if the entity involved in the statement is (is not) a part of that domain, the existential statement is true (false). Where antirealists deny that there is any correspondence between furnished worlds and the World, friends of (EMQ) are agnostic. The demarcation is quite substantial. Antirealists deny that the predicate ‘being REALLY true’ makes any sense at all. The quietism here presented is instead agnostic: such a predicate is meaningful but, given our epistemic access to the World, we cannot evaluate when a sentence is REALLY true (or REALLY false). What we are left with is the truth and falsehood in certain contexts, as previously presented. So the (EMQ) that I have in mind, to which I will refer simply as ‘quietism’ in what follows, consists in the acceptance of (1), an agnostic stance toward (2) and a dismissal of (4).

The positive thesis that quietism delivers is the following: despite the fact that different contexts pick different furnished functions, there is a privileged context among all. Namely, the furnished world, that I dub the ‘empirical furnished world’. The ‘empirical world’ is our best attempt to provide a coherent description of the World. Metaphysical and scientific disagreements concern, in this quietists view, what should be added or discarded from this privileged furnished world.Footnote 29 Nonetheless, no matter how coherent and exhaustive this picture could be, the quietist claims that we cannot know if it REALLY depicts the World for how it is structured. This kind of irretrievable scepticism was clearly pointed out by Planck during a lecture he gave on the occasion of his promotion at the University of Berlin:

Let us suppose that a Physical representation of the Universe had been found which fulfils all our demands, and therefore one that can completely and accurately represent all laws of Nature empirically known; still that that image even remotely resembles “real” Nature, can in no way be proven. [...] Even in Physics, the phrase holds good that “There is no Salvation without Faith,” – at least a faith in a certain reality outside ourselves. (Planck 1914, pp. 69–70)

As a consequence, quietists do not deny that all these objects exist (even if nobody is looking at them). What they are agnostic about is if this way of partitioning reality (i.e. to assign different names to different portions of the world) reflects how the World is. In other words, whether we can know what the mind-independent structure of the World is.

This empirical reformulation of realism is similar to the ‘empirical realism’ endorsed by some Neo-Positivists.Footnote 30 As with my acknowledgement of a privileged furnished world, their realism was no committed to referring to the structures of the external World. In other words, as in (EMQ), existential claims were not interpreted by Neo-Positivists to be understood in metaphysically loaded terms, i.e. as describing what exists in the World. Despite the similarities between my quietism and Neo-Positivists’ empirical realism, a great difference separates us. My view is that everyday objects exist. What I am agnostic on is whether they REALLY exist, in the sense previously defined, i.e. if this portion of the matter I called ‘the chair’, say, reflects a way in which the World itself is partitioned. Neo-Positivists, on the other hand, consider both metaphysical realism and antirealism, insofar as they exceed human beings’ possible experience, meaningless.Footnote 31 Therefore, their view is more similar to (DMQ) rather than to (EMQ).

4 A Scientific Realism Without ‘Reality’

As we have seen, rejecting metaphysical realism does not entail holding metaphysical antirealism: quietism, a third view standing in between, is indeed available. It is time, then, to come back to our original question: is it possible to be scientific realists without holding any metaphysical commitment? To show that it is possible, I think it is sufficient to argue that two quietists may disagree over the existence of unobservable scientific entities. In other words, even assuming metaphysical quietism, we can still make sense of scientific realism and of antirealism. That it is possible should follow from what I have argued so far.

As argued in (Sect. 2), the minimal claim that scientific realists must hold is that ‘Unobservable entities posited by our best scientific theories are at least as real as everyday entities’ (MC). It follows that every kind of scientific realism must at least hold (MC) and every form of scientific antirealism must deny it. Remember now that in (Sect. 3.2), two predicates have been introduced, namely, that of ‘being true’ and that of ‘being REALLY true’. For the metaphysical realists, when we speak in a metaphysically loaded way, we are discussing what REALLY exists (i.e. of REALLY true existential claims) rather than of what exists in a given furnished world. For the metaphysical realists then, it is what REALLY exists that matters. When philosophers debate whether, say, mathematical entities, moral values and universal properties exist, according to metaphysical realists, they are discussing whether they REALLY exist and not if they exist in a given domain. In the metaphysical realists’ terms then, two entities are metaphysically on par if they both REALLY exist or if they both exist in the same domain.

According to the quietist’s picture described in (Sect. 3.3), we should not use such a notion of REALLY existing: even if it is not meaningless, it is in principle impossible, or so the quietists argue, to verify whether an existential claim is REALLY true or not. Hence, ‘metaphysically on par’ might mean, in the quietists’ picture, being a member of the same furnished world. Note that furnished worlds are just named sets of entities. Therefore, two given entities are always metaphysically on par if it means just being members of the same set. Indeed, given two entities, there is always a set that has both as members. There is an easy way out of such an impasse. We have seen that there is a privileged furnished world in the quietist’s picture, i.e. the ‘empirical’ one. Such a furnished world contains all the entitiesFootnote 32 that are necessary to make the most accurate and coherent picture of what surrounds us. The ‘empirical furnished world’ is our ‘best theory’ of how the World could be. We postulate that ‘metaphysically on par’ means, according to the quietists, to be a member of this furnished world.Footnote 33

Undoubtedly, such a theory does not exist yet. Indeed, quietists argue that philosophers and scientists alike disagree exactly to what such a picture of reality should amount to: rather than speaking of the mind-independent structure of the World, they debate what should be added or removed from our best description of it, i.e. what I dubbed the ‘empirical furnished world’. Three-dimensionalists will, for example, disagree with four-dimensionalists over whether four-dimensional objects should be members of this empirical furnished world. At the same time, String theorists and friends of Loop Quantum Gravity will disagree over which fundamental physical entities provide us with the best empirical furnished world. In the quietists’ eyes, philosophical and scientific disagreement amounts to a fight for delivering the best (i.e. empirically adequate, coherent, simple and so on) description of the World. At the same time, though, the quietists join these metaphysical and physical debates with the awareness that the issue of whether their favourite picture is REALLY true cannot be settled. This is not to say that in the eyes of the quietists then, all these debates are unsubstantial or futile. Instead, they are our best shot for understanding reality. But whether our best shot, the quietists add, hits its target, is a question doomed to be left unanswered.Footnote 34

With this notion of metaphysically on par, i.e. being a member of what is taken to be the right furnished world, we can make sense of the disagreement between scientific realists and antirealists. The quietists who recognize themselves as scientific realists will endorse what I dub ‘Quiet Scientific Realism’. According to such a view, we have to subscribe to (MC) and, following Fine’s ‘homely line’, we must trust the scientific enterprise in the same way in which we trust our everyday experience. As a consequence, the quiet scientific realists will claim that unobservable entities, as posited by our best scientific theories, are at least as real as everyday objects. The best description of the World available to us must include those entities. As we believe that tables, chairs and all the everyday objects exist, we must accept that electrons, viruses and black holes exist in the very same sense: their existence is necessary for our best description of the phenomena that surround us. At the same time, quiet scientific antirealists will deny that. They will insist that as, say, numbers exist only in the furnished world picked in particular contexts (e.g. when we are in a math course), unobservable scientific entities exist in the same way. We are allowed to speak of their existence only when we are in a laboratory or, say, during scientific courses at the university. Therefore, our best description of the World should be devoid of those entities, either because those entities do not exist in the same sense in which everyday objects do, i.e. they are fictions, or because we are not rationally entitled to believe in them. Following Van Fraassen (1980), a quiet scientific antirealist may argue that we do not have enough ground for believing in unobservable entities as we believe in everyday objects. As a consequence, our best (in the sense of rationally justified) description of nature must not contain all the scientific entities of which we have no certainty of their existence.

We could define this new form of scientific realism mimicking Psillos (2005)’s definition of scientific realism: Quiet Scientific Realism is a threefold thesis that has a semantic, an epistemic and a metaphysical component. The semantic component consists in the claim that scientific theories must be taken at face value and that they can be true or false, both in their observable and unobservable domain.Footnote 35 The epistemic thesis is the claim that the scientific inquiry allows us to give a better description of the World. As such, unobservable entities posited by our best scientific theories must be part of our best description of the World. Finally, the metaphysical component is quietism itself. Albeit there is a World and the scientific enterprise allows us to understand it better, it is impossible to say whether it has a mind-independent structure and if our theories REALLY reflect it.

5 Conclusion

The question addressed in the paper was whether scientific realists could weaken their metaphysical commitment. I argued that scientific realism could be combined with a view that is neutral on the debate over the existence of a mind-independent external world, i.e. with quietism. In order to show it, I argued that even assuming a peculiar form of quietism, it is still possible to make sense of the debate between scientific realists and antirealists.

The combination of scientific realism and metaphysical quietism, which I dub ‘Quiet Scientific Realism’, may leave many scientific realists disappointed. As a matter of fact, many scientific realists spontaneously want to subscribe to metaphysical realism to strengthen their claim. They could argue, indeed, that Quiet Scientific Realism is too weak to be of any interest. Still, the paper has aimed to argue in favour of the possibility of formulating scientific realism without a metaphysical commitment. To reach a definite conclusion to such a question, I take the possibility of making sense, assuming quietism, of scientific realism and antirealism to be enough. Therefore, pointing out how weak Quiet Scientific Realism is leaves the point I wanted to make in the present paper untouched. Such a fact explains why I did not defend Quiet Scientific Realism over its competitors nor give a positive argument in favour of dismissing metaphysical realism. Nonetheless, I will sketch as a conclusion a couple of reasons why such a weak form of scientific realism is interesting and worth exploring.

Firstly, it is true that Quiet Scientific Realism is weak. At the same time, though, weak theses are generally more defensible than stronger ones. Different philosophical theses are committed to scientific realism, and, precisely on this basis, harshly criticized.Footnote 36 To the friends of these views, Quiet Scientific Realism should be of some interest. Given the commitment to some form of scientific realism, Quiet Scientific Realism should be seen as less costly, as a commitment, than other forms of scientific realism.

Moreover, despite a strong scientific realist intuition, one may be disappointed by the general strategy of such a view. The pessimistic meta-induction (Laudan 1981) is arguably one of the most persuasive arguments in favour of scientific antirealism. This argument starts with the observation that in the history of science, many times unobservable entities posited by what were considered the best scientific theories of the time ceased to be taken seriously by later theories. Since human beings’ epistemological situation is no better now than it was in the past, the pessimistic meta-induction concludes, we should not believe in unobservable entities posited by our current scientific theories. Quiet Scientific Realism could be attractive as an answer to these kinds of arguments. Firstly, because one may want to invert the general dialectic of scientific realism. Rather than claiming from the very beginning that some unobservable entities that scientific theories postulate do exist, one may prefer a safer approach: to endorse a weaker form of scientific realism and then argue for the mind-independent existence of different scientific entities case by case. Finally, since Quiet Scientific Realism explicitly admits that whether our current theories’ hold on reality cannot be settled, the pessimistic meta-induction loses its mordent. Indeed, the arguments in favour of scientific realism are arguments, according to the quietists, in favour of the fact that scientific entities, both observable and unobservable, must be members of the empirical furnished world. Quiet Scientific Realism admits from the very beginning that such a picture might be revised in the future. Instead of claiming that the unobservable entities posited by our current scientific theories REALLY exist, quiet scientific realists can hold a weaker claim: there are reasons to think that some of them more likely will remain in our best description of the world, while others probably will be replaced in future theories. At the same time, though, the core of this position is that our best picture of the World must contain these unobservable entities. Even with the awareness that eventually such a picture could turn out to be false, the fact that, currently, it is the best one, makes it rational to believe in it. As an answer to the pessimistic meta-induction, the friend of Quiet Scientific Realism could reply with the rhetorical question ‘In what else should I believe?’.

Notes

For example, they are false because the unobservable entities posited by our best scientific theories do not exist. Others claim that scientific truth is not in correspondence with the reality, but something else, e.g. ‘empirical adequacy’.

Henceforth, only ‘mind-independent’ will be used for the rest of the paper. If the reader holds an antirealist view according to which some kinds of entities depend on something else, he/she could read his/her favourite kind of dependency instead of ‘mind-’.

i.e. no argument shows that accepting one of them entails a commitment to the other.

I thank an anonymous referee for bringing to my notice that Devitt’s and Psillos’s stances toward the necessity of metaphysical realism are problematic for the view I sketch in the present paper.

The structure of Alice’s argument is that of the well known ‘No-Miracle Argument’ (Putnam 1975, p. 73).

Even if scientific realists disagree on this point, I think that trying to recombine them is an essential part of the scientific enterprise. For a defence of this claim, see for example: Sankey (forthcoming).

This claim is not at odds with a metaphysical picture according to which reality is made of different layers. According to this view, our everyday reality somehow emerges from a more fundamental level (as described by some theory of quantum gravity, say). Indeed, what is experienced daily and what exists fundamentally are, even if at different ‘levels’, part of the very same reality.

Reductionists (according to whom only fundamental entities discovered by science exist) might be disappointed by such a claim. Note though that (MC) is, indeed, quite minimal: it says that scientific entities are at least metaphysically on par with everyday entities. Therefore, to claim that only the former exist, or they are more fundamental, do not contradict per se (MC).

Musgrave (1989) argues that NOA can be interpreted in two ways: (i) as a standard form of scientific realism or (ii) as a form of quietism about the debate that avoids any philosophical commitment, metaphysical realism included. As we will see in what follows, the view I present instead assumes a form of metaphysical quietism, without ceasing to be a form of scientific realism. I thank an anonymous referee for insightful comments on this point.

As Fine (1986, p. 175) explicitly reckons: “NOA allies itself with what Blackburn [...] dismissively calls ‘quietism’ ”.

Albeit metaphysical antirealism is philosophically out of fashion, it is worth noticing that recently it has been defended by some scientists, on scientific rather than purely philosophical grounds (for example: d’Espagnat 1979). Notably, the most famous advocate of some form of metaphysical antirealism is the physicist Wheeler (1989).

Cf. Miller 2016.

Chalmers’ machinery is preferred here among other earlier attempts to regiment similar notions, e.g. Carnap’s frameworks and the distinction between internal and external questions. This is so because earlier attempts, at least those that I am aware of, assume a syntactic account of scientific theories. Chalmers’ machinery instead, can be naturally employed also when a semantic view is endorsed. Indeed, Chalmers’ notion of truth in a model is strikingly similar to that of ‘truth in a structure’ presented by Hodges (1985). I thank two anonymous referees for their helpful remarks on this point.

To stick to the example of three-dimensionalism vs four-dimensionalism, such a claim has been argued, for instance, by Miller (2004).

Contra Putnam’s (1982) idea that metaphysical realism entails a belief in the ‘One True Theory’.

Sophisticated Metaphysical Realism has been defended, for example, by Field (1982), against Putnam’s thesis that metaphysical realism entails the belief in a ‘one true theory’.

For example, in contrast to the example above concerning three- and four-dimensionalism, a metaphysical realist could hold a ‘pluralistic’ view according to which different metaphysical theses capture different aspects of the same reality.

Of course, a friend of Platonism (i.e. the view that abstract mathematical entities exist) would disagree. According to Platonists, these abstract entities REALLY exist as tables, chairs, and so on, do. Here, I am not arguing against Platonism. Rather, I am using nominalism on mathematical entities just as an example.

Even if this is true for the majority of scientific realists, a minority do specify the form of metaphysical realism endorsed. See for example Massimi (2018).

Fuchs (2016) argued that quantum mechanics cries out for a revision of the commitment to metaphysical realism. Arguably, many other interpretations, like many world and relational quantum mechanics, are at odds with a strong version of metaphysical realism

This is so for all the debates that oppose realists and antirealists about some entities a, b and c of the same kind. In what follows, unless otherwise specified, ‘quietism’ will stand for ‘metaphysical quietism’.

See for instance Descartes’ argument of the evil daemon (in the Meditations on First Philosophy), or Putnam (1981)’s famous ‘brains-in-a-vats’ argument against metaphysical realism.

Such a preferred description corresponds to what I dub, later on, the ‘empirical furnished world.’ I thank an anonymous referee for pressing me to clarify this crucial point of the paper.

As said, the naïve way to characterize the ‘empirical furnished world’ is that of starting from our experience and claim that members of it are the everyday objects. But since metaphysical and scientific considerations enrich such a description of reality, it could be that no everyday object is part of it. The empirical furnished world is built starting from our experience. However, it does not mean that it must stop at it, or that metaphysics and scientific enterprises could not be revisionary. At the same time though, to eliminate everyday objects from the empirical furnished world, these theories must also explain (i) why we perceive them and (ii) which entities play the causal role that we think everyday objects have.

As, for example, the empirical realism accepted by Schlick (1932).

Inevitably, a list of entities will not be enough for delivering the best description of the World. Indeed, also some structure (i.e. relations between these entities, properties, laws of nature, and so on) will need to have a coherent description of the world. Chalmers (2009) sketches how the machinery can be implemented in order to add structures to these sets. For length reasons, I will continue to consider furnished worlds as if they were simply sets of entities.

Quietism is compatible with the idea that such a furnished world might not be unique: there may be two (or more) views of the world, equivalent in a certain sense. Choosing between the two then would be a matter of preferences in meta-philosophical principles, i.e. for example, which super-empirical virtues are considered better than others.

I.e. it cannot have a definite and certain answer. But this does not entail that we do not have any reason to say that some descriptions of the world have higher probabilities of being really true rather than others.

One could object that if the world does not have any mind-independent structure, it would be impossible for a scientific theory to be true. There is no space to address such an objection here. Nonetheless, there have been put forward in the literature different attempts to explain how theory could be true without assuming that the phenomena investigated by it have any structure in and of themselves. See, for example: Giunti (2016).

For example, Jaksland (2016) criticizes on this basis the naturalized approach to metaphysics.

References

Carnap, R. (1950). Empiricism, semantics, and ontology. Revue Internationale de Philosophie, 4(11), 20–40.

Carnap, R. (1966). Scheinprobleme in der philosophie (1928). Hg von Günther Patzig Frankfurt a M.

Chakravartty, A. (2007). A metaphysics for scientific realism: Knowing the unobservable. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chakravartty, A. (2017). Scientific realism. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Summer 2017 Edition).

Chalmers, D. J. (2009). Ontological anti-realism. In D. J. Chalmers, D. Manley, & R. Wasserman (Eds.), Metametaphysics: New essays on the foundations of ontology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

d’Espagnat, B. (1979). The quantum theory and reality. Scientific American, 241(5), 158–181.

Devitt, M. (1991). Realism and Truth. Oxford: Blackwell.

Dorato, M. (2010). Physics and metaphysics: Interaction or autonomy? Humana Mente, 4(13), 1–11.

Feigl, H. (1943). Logical empiricism. In D. D. Runes (Ed.), Twentieth century philosophy (pp. 371–416). New York: Philosophical Library.

Field, H. (1982). Realism and relativism. Journal of Philosophy, 79(10), 553–567. https://doi.org/10.2307/2026317.

Fine, A. (1984a). And not anti-realism either. Noûus, 18(1), 51–65. https://doi.org/10.2307/2215021.

Fine, A. (1984b). The natural ontological attitude. In J. Leplin (Ed.), Scientific realism (pp. 261–277). University of California Press.

Fine, A. (1986). Unnatural attitudes: Realist and instrumentalist attachments to science. Mind, 95(378), 149–179. https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/XCV.378.149.

Fine, K. (2008). In defence of three-dimensionalism. Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplement, 62, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1358246108000544.

Fine, K. (2009). The question of ontology. In D. Manley, R. Wasserman, & D. J. Chalmers (Eds.), Metametaphysics: New essays on the foundations of ontology (pp. 157–177). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fuchs, C. A. (2016). On participatory realism. https://arxiv.org/abs/1601.04360.

Giunti, M. (2016). A real world semantics for deterministic dynamical systems with finitely many components. In L. Felline, A. Ledda, F. Paoli, & E. Rossanese (Eds.), New directions in logic and the philosophy of science (pp. 97–110). London: College Publications. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.3838.1923/1.

Hirsch, E. (2008). Language, ontology, and structure. Noûs, 42(3), 509–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0068.2008.00689.x.

Hirsch, E. (2009). Ontology and alternative languages. In D. Manley, R. Wasserman, & D. J. Chalmers (Eds.), Metametaphysics: New essays on the foundations of ontology (pp. 231–58). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hodges, W. (1985). Truth in a structure. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 86, 135–151.

Jaksland, R. (2016). The possibility of naturalized metaphysics. PhD thesis, University of Copenhagen

Khlentzos, D. (2016). Challenges to metaphysical realism. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (2016th ed.). Stanford: Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

Laudan, L. (1981). A confutation of convergent realism. Philosophy of Science, 48(1), 19–49. https://doi.org/10.1086/288975.

Massimi, M. (2018). Four kinds of perspectival truth. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 96(2), 342–359. https://doi.org/10.1111/phpr.12300.

McDowell, J. (1994). Mind and World. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

McMullin, E. (1984). A case for scientific realism. In J. Leplin (Ed.), Scientific realism (pp. 8–40). Oakland: University of California.

Miller, A. (2016). Realism. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2016th ed.). Stanford: Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

Miller, K. (2004). The metaphysical equivalence of three and four dimensionalism. Erkenntnis, 62(1), 91–117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-004-2845-8.

Musgrave, A. (1989). Noa’s ark-fine for realism. Philosophical Quarterly, 39(157), 383–398. https://doi.org/10.2307/2219825.

Planck, D. M. (1914). Ix. new paths of physical knowledge: being the address delivered on commencing the rectorate of the Friedrich-Wilhelm University, Berlin, on October 15th 1913. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, 28(163), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786440708635184.

Price, H. (2009). Metaphysics after carnap : The ghost who walks? In D. Manley, R. Wasserman, & D. J. Chalmers (Eds.), Metametaphysics: New essays on the foundations of ontology (pp. 320–46). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Psillos, S. (1999). Scientific realism: How science tracks truth. Abingdon: Routledge.

Psillos, S. (2005). Scientific realism. Encyclopedia of philosophy. Farmington Hills: Gale Macmillan Reference.

Putnam, H. (Ed.) (1975). What is mathematical truth? In Mathematics, matter and method (pp. 60–78). Cambridge University Press.

Putnam, H. (1981). Reason, truth and history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Putnam, H. (1982). Why there isn’t a ready-made world. Synthese, 51(2), 205–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00413825.

Rescher, N. (2010). Reality and its appearance. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Rosen, G. (1994). Objectivity and modern idealism: What is the question? In M. Michael & J. O’Leary-Hawthorne (Eds.), Philosophy in mind (pp. 277–319). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Sankey, H. (forthcoming). Scientific realism and the conflict with common sense. In: W. Gonzalez (Ed.), New approaches to scientific realism. De Gruyter

Schlick, M. (1932). Positivismus und realismus. Erkenntnis, 3(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01886406.

Sider, T. (2001). Four dimensionalism: An ontology of persistence and time. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sider, T. (2009). Ontological realism. In D. Manley, R. Wasserman, & D. J. Chalmers (Eds.), Metametaphysics: New essays on the foundations of ontology (pp. 384–423). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sider, T. (2011). Writing the book of the world. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Van Fraassen, B. C. (1980). The scientific image. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wheeler, J. A. (1989). Information, physics, quantum: The search for links. In: Proceedings III international symposium on foundations of quantum mechanics (pp. 354–358)

Wright, J. (2018). An epistemic foundation for scientific realism. Berlin: Springer.

Wrigley, W. (2018). Sider’s ontologese introduction instructions. Theoria, 84(4), 295–308. https://doi.org/10.1111/theo.12153.

Acknowledgements

The paper started as a joint work with Lucy James. After a while, we realized that we agreed just on how much we disagree, ending our collaboration. Even though the paper diverges from the original intentions, it is fair to acknowledge that our discussions on this topic have been more helpful than what could be expressed in a couple of lines. I would also like to thanks the audience of the seminar Metaphysics of Science at the University of Geneva, of the 46th Annual Philosophy of Science Workshop in Dubrovnik and of the 4th SILFS postgraduate conference in Urbino, for helpful comments and suggestions. Finally, I want to thanks Mario Alai, Vincenzo Fano, Frida Trotter and two anonymous referees for precious comments on earlier drafts of the paper.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Urbino Carlo Bo within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Corti, A. Scientific Realism Without Reality? What Happens When Metaphysics is Left Out. Found Sci 28, 455–475 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10699-020-09705-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10699-020-09705-w