Abstract

It is well known that participation in education is incompatible with the transition to motherhood. However, enrolment is overwhelmingly treated as a single status even though participation in education may be combined with employment—resulting in double-status positions, and the fertility implications of double-status positions are less clear-cut. Relying on normative and economic approaches, we develop original and competing hypotheses regarding the effect of double-status positions on the transition to motherhood. We also speculate on how the post-communist transition and institutional context might influence the hypothesised effects. The hypotheses are tested using event history data from the Hungarian Generations and Gender Survey. We employ event history methods, which take into account the potential endogeneity of employment and enrolment decisions. We find robust evidence that first birth rates are higher among women in double-status positions than among women who are merely enrolled, but that difference is smaller in younger cohorts than in older ones. We also find some evidence that first birth rates are lower in double-status positions than among women who are employed but not enrolled. Our findings suggest that the conflict between participation in education and motherhood is mitigated in double-status positions, especially among members of the oldest cohort. Since double status is prevalent in modern societies, but has different meanings in different contexts according to educational system and welfare state, we argue for future research on this issue.

Source: Own calculation, based on education statistics, Hungarian Central Statistical Office

Source: Own calculation, based on education statistics, Hungarian Central Statistical Office

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Here we discuss only those aspects of the economic approach that focus on investments in human capital.

For reasons of simplicity, the present discussion as well as subsequent derivations of hypotheses neglects the partners. We are of course aware of theories and empirical research that explore the effect of a partner’s income and education on the fertility behaviour of women. Nevertheless, partner effects of this kind are not considered in the present paper.

Detailed analysis of the post-socialist transition and an outline of the Hungarian context are beyond the scope of the present paper. For a more detailed overview about institutional changes related to life-course transitions, see Spéder et al. (2010).

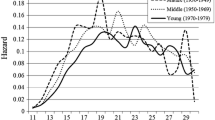

In our empirical study, women born in 1961–1965 and in 1975–1983 are used to represent old and young cohorts.

Marxist–Leninist political science degrees necessary to obtain higher (cadre) positions could be acquired via distant learning, but there were also other degrees obtainable through part-time education.

Educational institutions were also interested in offering part-time educational programmes because they were allowed to charge fees to part-time students. Full-time education, in contrast, was free of charge during the 1990s and 2000s.

For simplicity, we refer to this dataset as the three waves of the Hungarian GGS.

During the analyses, we also estimated models in which partnership status was included. However, the inclusion of partnership status does not affect our conclusions. However, the inclusion of partnership status immediately raises the concern of endogeneity.

The model is estimated using version 14 of Stata, with the help of the cmp module (Roodman 2011).

See Sect. 3.2 for the specification of the selection model and the estimation method.

References

Aassve, A., Billari, F. C., & Spéder, Zs. (2006). Societal transition, policy changes and family formation: Evidence from Hungary. European Journal of Population, 22(2), 127–152.

Adsera, A. (2004). Changing fertility rates in developed countries. The impact of labour market institutions. Journal of Population Economics, 17(1), 17–43.

Andersson, G. (2000). The impact of labour-force participation on childbearing behaviour: Pro-cyclical fertility in Sweden during the 1980s and the 1990s. European Journal of Population, 16(4), 293–333.

Balbo, N., Billari, F. C., & Mills, M. (2013). Fertility in advanced societies: A review of research. European Journal of Population, 29(1), 1–38.

Bartus, T., & Roodman, D. (2014). Estimation of multiprocess survival models with cmp The Stata Journal, 14(4), 756–777.

Bartus, T., Murinkó, L., Szalma, I., & Szél, B. (2013). The effect of education on second births in Hungary: A test of the time-squeeze, self-selection and partner-effect hypotheses. Demographic Research, 28(1), 1–32.

Beerkens, M., Mägli, E., & Lill, L. (2011). University studies as a side job: Causes and consequences of massive student employment in Estonia. Higher Education, 61(6), 679–692.

Blossfeld, H. P. (1995). Changes in the process of family formation and women’s growing economic independence: A comparison of nine countries. In H. P. Blossfeld (Ed.), The new role of women: Family formation in modern societies (pp. 3–23). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Blossfeld, H.-P., & Huinink, J. (1991). Human capital investment or norms of role transition? How women’s schooling and career affect the process of family formation. American Journal of Sociology, 97(1), 143–168.

Brunello, G., Crivellaro, E., & Rocco, L. (2010). Lost in transition? The returns to education acquired under communism 15 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall. IZA Discussion Papers 5409, Institute for the Study of Labour (IZA).

Buchmann, M. C., & Kriesi, I. (2011). Transition to adulthood in Europe. Annual Review of Sociology, 37, 481–503.

Darmody, M., & Smith, E. (2008). Full-time students? The growth of employment among higher education students in Ireland. Journal of Education and Work, 21(4), 349–362.

Elder, G., Jr. (1974). Children of the great depression: Social change in life experience. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Frejka, T. (2008). Overview Chapter 5: Determinants of family formation and childbearing during the societal transition in Central and Eastern Europe. Demographic Research, 19, 139–170.

Goode, W. J. (1960). A theory of role strain. American Sociological Review, 25(4), 483–496.

Gustafsson, S. (2001). Optimal age at motherhood. Theoretical and empirical considerations of postponement of maternity in Europe. Journal of Population Economics, 14(2), 225–247.

Hoem, J. (1986). The impact of education on modern family-union initiation. European Journal of Population, 2(2), 113–133.

Huinink, J. (1995). Warum noch Familie? Zur Attraktivität von Partnerschaft und Elternschaft in unserer Gesellschaft. Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag.

Impicciatore, R., & Billari, F. C. (2012). Secularization, union formation practices, and marital stability: Evidence from Italy. European Journal of Population, 28(2), 119–138.

Inglehart, R. (1977). The silent revolution. Changing values and political styles among Western publics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kantorová, V. (2004). Education and entry into motherhood: The Czech Republic during state socialism and the transition period (1970–1997). Demographic Research Special Collection, 3, 245–274.

Kertesi, G., & Köllő, J. (2002). Economic transformation and the revaluation of human capital—Hungary, 1986–1999. In A. de Grip, J. Van Loo, & K. Mayhew (Eds.), The economics of skills obsolescence: Theoretical innovations and empirical applications (Vol. 21, p. 235). Amsterdam: Elsevier. Research in labour economics.

Kézdi, G. (2005). Education and labour market success. In K. Fazekas & J. Varga (Eds.). The Hungarian labour market: Review and analysis 2005 (pp 31–37). Budapest: Institute of Economics, HAS and Hungarian Employment Foundation, Budapest. http://econ.core.hu/doc/mt/2005/en/infocus.pdf.

Kohler, H.-P., Billari, F. C., & Ortega, J. A. (2002). The emergence of lowest-low fertility in Europe during the 1990s. Population and Development Review, 28(4), 641–680.

Korintus, M. (2010). Hungary. In P. Moss (Ed.), International review of leave policies and related research 2010 (pp. 115–141). London: Department for Business, Innovation and Skills.

Kornai, J. (1980). Economics of shortage. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Lalive, R., & Zweimüller, J. (2009). How does parental leave affect fertility and return to work? Evidence from two natural experiments. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(3), 1363–1402.

Lappegard, T., & Ronsen, M. (2005). The multifaceted impact of education on entry into motherhood. European Journal of Population, 21(1), 31–49.

Liefbroer, A. C., & Billari, F. C. (2010). Bringing norms back. A theoretical and empirical discussion of their importance for understanding demographic behaviour. Population, Space and Place, 16(4), 287–305.

Liefbroer, A., & Corijn, M. (1999). Who, what, where and when? Specifying the impact of educational attainment and labour force participation on family formation. European Journal of Population, 15(1), 45–75.

Lucas, S. R., Fucella, P. N., & Berends, M. (2011). A neo-classical education transitions approach: A corrected tale for three cohorts. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 29(3), 263–285.

Luci-Greulich, A., & Thévenon, O. (2013). The impact of family policies on fertility trends in developed countries. European Journal of Population, 29(4), 387–416.

Makay, Z. (2015). Family support system, childraising, employment. In J. Monostori, P. Őri, Z. Spéder (Eds.), Demographic portrait of Hungary, 2015 (pp. 57–74). Budapest: Hungarian Demographic Research Institute. On-line: http://demografia.hu/en/publicationsonline/index.php/demographicportrait/article/view/885/647.

Makay, Z., & Blaskó, Z. (2012). Family support system—childraising—employment. In P. Őri, Z. S. Spéder (Eds.). Demographic portrait of Hungary 2012 (pp 45–56). Budapest: Demographic Research Institute. On-line: http://demografia.hu/en/publicationsonline/index.php/demographicportrait/article/view/817/274.

Martin-Garcia, C., & Baizan, P. (2006). The impact of the type of education and of educational enrolment on first births. European Sociological Review, 22(3), 259–275.

Matyisak, A., & Vignoli, D. (2008). Fertility and women’s employment: a meta-analysis. European Journal of Population, 24(4), 363–384.

Mayer, K. U. (2001). The paradox of global social change and national path dependencies: Life course patterns in advanced societies. In A. E. Woodward & M. Kohli (Eds.), Inclusions and exclusions in European societies (pp. 89–110). London: Routledge.

Mills, M. (2007). Individualization and the life course: Towards a theoretical model and empirical evidence. In C. Howard (Ed.), Contested individualization: Political sociologies of contemporary personhood (pp. 61–79). London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Neels, K. & De Wachter, D. (2010). Postponement and recuperation of Belgian fertility: How are they related to rising female educational attainment? Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 8, 77–106.

Ní Bhrolcháin, M. N., & Beaujouan, E. (2012). Fertility postponement is largely due to rising educational enrolment. Population Studies, 66(3), 311–327.

Rindfuss, R.R., & Brewster, K.L. (1996). Childrearing and fertility. Population and Development Review, 22, Supplement: Fertility in the United States: New Patterns, New Theories, 258–289.

Róbert, P., & Saar, E. (2012). Learning and working: The impact of the ‘double status position’ on the labour market entry process of graduates in CEE Countries. European Sociological Review, 28(6), 742–754.

Roodman, D. (2011). Fitting fully observed recursive mixed-process models with cmp. The Stata Journal, 11(2), 159–206.

Ryder, N. B. (1965). The cohort as a concept in the study of social change. American Sociological Review, 30(6), 843–861.

Sobotka, T. (2002). Ten years of rapid fertility changes in the European post-communist countries. Evidence and interpretation. University of Groningen, Population Research Centre, Working Paper Series 02-1, p. 53.

Sobotka, T. (2011). Fertility in Central and Eastern Europe after 1989: Collapse and gradual recovery. Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung, 36(2), 246–296.

Spéder, Zs., Kapitány, B., & Neumann, L. (2010). Life-course transitions and the Hungarian employment model before and after the societal transformation. In D. Anxo, G. Bosch, & J. Rubery (Eds.), The welfare state and life transitions (pp. 287–327). Cheltenham—Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Szeleva, D., & Polakowski, M. P. (2008). Who cares? Changing patterns of childcare in Central Eastern Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 18(2), 115–131.

Thornton, A., & Philipov, D. (2009). Sweeping changes in marriage, cohabitation and childbearing in Central and Eastern Europe: New insights from the developmental idealism framework. European Journal of Population, 25(2), 123–156.

Thornton, A., Axinn, W. G., & Teachman, J. D. (1995). The influence of school enrolment and accumulation on cohabitation and marriage in early adulthood. American Sociological Review, 60(5), 762–774.

Upchurch, D. M., Lillard, L. A., & Panis, C. W. A. (2002). Nonmarital childbearing: Influences of education, marriage, and fertility. Demography, 39(2), 311–329.

Vikat, A., Spéder, Zs., Beets, G., Billari, F. C., Bühler, Ch., Désesquelles, A., et al. (2007). Generation and Gender Survey (GGS), towards a better understanding of relationships and processes in the life course. Demographic Research, 17, 389–440.

Wolbers, M. H. J. (2003). Learning and working: double statuses in youth transitions. In W. Müller & M. Gangl (Eds.), Transitions from education to work in Europe (pp. 131–155). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the anonymous referees for helpful comments and suggestions. The research was supported by the grant “Mapping Family Transitions: Causes, Consequences, Complexities, and Context” (No. K 109397) of the Hungarian Science and Research Foundation (OTKA). Bartus also received financial support from the János Bolyai Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Spéder, Z., Bartus, T. Educational Enrolment, Double-Status Positions and the Transition to Motherhood in Hungary. Eur J Population 33, 55–85 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-016-9394-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-016-9394-0