Abstract

Despite prosecutors’ difficulties in proving corporate bribery, nearly all enforcement actions end with a settlement at the pretrial stage. Compared to court proceedings, settlement-based enforcement provide prosecutors with flexibility to reward offenders’ self-reporting and cooperation, and reach quicker conclusions to complex cases. In this article, we explain, such enforcement needs regulation to minimize potentially harmful side-effects. When the difference between a court and settlement sanction exceeds a certain size, the alleged offender accepts a settlement regardless of actual responsibility of misconduct. For the prosecutor, the option of offering a lenient settlement means weaker incentives to ascertain the material facts of the case. Society receives less information about the blameworthy act, little opportunity to evaluate the sanction, and less reason to expect sanctions to deter bribery. We show why such consequences result in under-deterrence of bribery and weaker rule of law. The use of settlement may have a self-escalating effect because the enforcement mode can reduce the predictability of the law, while a defendant’s inclination to accept a settlement offer depends on the predictability of the law. Our results suggest that United Kingdom’s current escalation of enforcement of corporate bribery laws will lead to a mixture of settlements and court decisions, while in the United States firms will continue to negotiate settlements as if there were no opportunity to have their cases tested in court.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In most cases of suspected international corporate bribery, prosecutors struggle to prove crime. Nonetheless, nearly all such cases are settled with a hefty fine at the pre-trial stage, even if the alleged corporate offender in many of these cases might have had a reasonable chance of being acquitted had the case been brought to court. For example, in August 2020 Herbalife Nutrition Ltd. agreed to pay the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) and the US Securities and Excange Comission (SEC) a fine of $122 million. By doing so, they ended the public investigation of their alleged violation of the US anti-bribery law, the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA).Footnote 1 In January 2020, Airbus SE agreed to pay €991 million to conclude a bribery case with the United Kingdom Serious Fraud Office.Footnote 2 In neither of these cases have there so far been pursued cases against individuals responsible for the alleged crime, which raises the question of how complete the information available to prosecutors may have been. No individuals have been convicted in the United Kingdom in cases where the firm has accepted a Deferred Prosecution Agreement. If there was a fair chance of being acquitted, what prevented these firms from bringing their cases to court?

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), whose latest enforcement statistics cover 27 jurisdictions, around two-thirds of all corporate bribery cases are settled at the pretrial stage, and this share has increased steadily over the last decade (OECD 2019). In the United States, nearly all cases take the form of a settlement, while in countries such as Germany and the United Kingdom, there is a mix. In Australia, Brazil, and the Netherlands, all cases to date have concluded with a settlement. Regulations across countries differ, for example with respect to judicial oversight, transparency, the prosecutor’s freedom to settle, the range of sanctions, and plea bargain traditions, not to mention the definition of corporate criminal liability. But the option of concluding cases without trial is available to prosecutors in all the aforementioned countries.Footnote 3

Which factors determine the enforcement mode - i.e. whether a case ends by trial or settlement - and the ensuing penalty decision in corporate bribery cases? What are the implications of such enforcement for the investigation, the likelihood of crime deterrence, and the information shared with the public? What is the optimal level of discretionary authority for the responsible public prosecutors, and what sorts of checks and balances ought to be in place for the sake of consistent enforcement and legitimacy? While the expanding use of settlements in corporate liability cases intensifies their policy relevance, up until now, there has been little best practice guidance for governments (Ivory and Søreide 2020). In December 2021, however, the OECD Working Group on Bribery (WGB) released revised recommendations attached to the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention, and these recommendations include principles that ought to influence governments’ regulation of settlement-based enforcement.Footnote 4 With respect to settlement-based enforcement, the purpose of the revisions was to protect the rule of law, promote the deterrent effect of sanctions, secure incentives for offenders’ to self-report and cooperate, and strengthen law enforcement transparency. The question is whether and what governments will do to implement these principles for efficient and accountable enforcement.

In this article we consider a concern that is not addressed by the 2021 OECD WGB Recommendations, namely the determinants and the consequences of the expected “sanction gap”. That ’gap’ is the difference between the sanction offered by a settlement and the expected sanction if the case is brought to court. We apply a central result in the literature on plea bargaining, namely the theory developed by Reinganum (1988) for individual offenders, and explain how results may differ when the defendant is a corporation. On this basis, we discuss the prosecutor’s incentives to place effort in investigation, the positive and negative sides of broad discretion for the prosecutor, the incentives to share information about the case with the public, and the dynamic implications of the use of settlements as an enforcement mode. Next, we present a review of regulations and enforcement practices. In particular, we compare enforcement systems in the United States and United Kingdom, finding that corporate offenders’ inclination to accept settlements is systematically higher in the former than in the latter. We focus on the United Kingdom and the United States as these are the two biggest enforcers of corporate bribery cases to date.

2 Economic analyses of settlement-based enforcement

Litigation, court decisions, and offenders’ inclination to accept an offered settlement have been subject to economic analysis for decades. Particularly relevant in this context are studies of plea bargaining, that is, situations where an offender ends the case by accepting a fine and admitting guilt. Corporate settlements rarely depend on confessions, yet the bargain is similar. The first analysis of such bargains characterized them as a transaction in which the prosecutor can obtain a guilty plea in exchange for promised leniency (Landes 1971). The probability of conviction in a trial, the severity of the crime, the prosecutor’s productivity, the defendant’s resources, litigation costs, and attitudes toward risk were presented as determinants of an offender’s choice to either accept a settlement or let the case go to court. Variants of the model followed within few years, including those by Rhodes (1976), Forst and Brosi (1977), and Weimer (1978). Authors increasingly tried to test their models’ power to predict individual case decisions, and in their models they sought to capture the distinct aims of crime reduction, maximization of cases concluded, and optimization of prosecutor effort per case. The analysis meanwhile took a new direction with Posner (1973), who used game theory to understand legal dispute resolution and was the first to investigate the effect of changes to procedural rules. His model captures a trade-off between types of costs, namely error cost, occurring when the prosecutor fails to fulfill her delegated tasks, and direct costs, such as costs for lawyers, judges, and security. Grossman and Katz (1983) explain why it matters to understand the defendant’s private information about the expected outcome of trial: plea bargain opportunities not only have the potential to reduce resources spent on law enforcement, but also induce the guilty and the innocent to self-select into their categories.

Reinganum (1988), a central reference for this study, explains the conditions that determine when a prosecutor will offer a settlement and when a defendant will accept the offer, given two different regimes of prosecutor discretionary authority. Introducing the factor of time to determine the importance of deadlines for law enforcement, Spier (1992) explains why many cases are settled close to the date when the case would proceed to court or a few days into the court proceedings. Kaplow and Shavell (1994) find that settlements may encourage self-reporting of crime, and they argue that the extent of leniency for firms that self-report should be higher if they self-report early than if they cooperate late in the process of investigation.Footnote 5 Dervan and Edkins (2013) demonstrate that innocent individuals are prone to accept settlements, despite their innocence, a situation we investigate for innocent firms.

With respect to the institutional context, Miceli (1996) describes the relevance of law enforcement hierarchy and highlights the potential conflict of interests between the legislator and the prosecutor. Miller (1987) investigates circumstances when more than two parties have an interest in the settlement, a situation that easily leads to conflict of interests and side payments. Tor et al. (2010) study how fairness influences a defendant’s decision to accept or reject a settlement.

A question that is less well resolved in this literature is how these results may vary when the alleged offender is a corporation. Procaccia and Winter (2017) explain why this constitutes a different sort of challenge, yet they focus mainly on the problem that a plea bargain with a corporation might let the natural person(s) who committed the crime off the hook, thus reducing employees’ incentives to prevent crime. The literature on the economics of corporate crime and enforcement explains how sanctions should be structured to induce corporations to prevent crime and self-report incidents when they happen (Mullin and Snyder 2009; Polinsky and Shavell 2000; Arlen and Kraakman 1997). What we address is the particular trade-off between settlement and court proceedings, a highly relevant matter in corporate bribery cases. The OECD Working Group on Bribery is expected to soon announce new official best-practice guidelines for governments in this area of law enforcement.

3 Theory

How can the difference between an expected sanction in court, and a certain sanction from a negotiated settlement alter a corporation’s decision-making, when choosing to accept or decline a settlement? And when will firms accept a settlement offer regardless of guilt? These are questions we seek to inform by first modeling the framework of negotiated settlements, when the defendant is a corporation, and not an individual.

Using a signaling model of plea bargaining with asymmetric information, Reinganum (1988) describes two different law enforcement regimes with different degrees of discretion for the prosecutor. Her framework for analysis is suitable for our study of corporate defendants because the mechanisms in the model capture central features of a corporate settlement agreement, considered from the distinct perspectives of prosecutors and defendants. The model was developed for analysis of enforcement against individual offenders. We explain why some results are different and more complex when the defendant is a powerful corporation. We begin by presenting our version of the theory and then modify some assumptions to make it fit our research question.

3.1 Benchmark model

Applying the analytic framework from Reinganum (1988) for our purpose, we consider a prosecutor (for now a she) who is faced with an alleged corporate offense. Based on her assessment of the available facts, she decides whether to pursue or dismiss the case, offer a settlement that ends the case at the pre-trial stage, or bring the case to court. The extent of prosecutorial discretion – classed as either limited or full discretion – determines her freedom to set the size of the offered settlement sanction. If she has limited discretion, the prosecutor has to offer the same sanction to defendants accused of the same crimes, while full discretion allows her to offer different sanctions in similar cases, taking into account factors beyond the type of crime, including the self-reporting by the offender. Reinganum considers the settlement offer subject to a guilty plea, while we assume that the settlement is offered without requiring the defendant (the firm) to plead guilty.

The model posits two types of defendants, an innocent and a guilty, subscripted i, g respectively. While the defendant’s type (innocent or guilty) is the firm’s private information, the distribution of guilt, known to both the defendant and the prosecutor, is such that an innocent defendant faces a weaker case than a guilty defendant, annotated \(\pi _i<\pi _g\). \(\pi \in [0,1]\) is the probability of conviction in court, which we assume represents the prosecutor’s perception of the strength of the case, and is the prosecutor’s private information. The strength of the case depends on the evidence in the hands of the prosecutor, which in practice depends on the resources available for the prosecutor, the complexity of the case, and the extent to which foreign enforcement agencies and the defendant itself cooperate and assist in the investigation. Efficient international collaboration between prosecutors can increase the size of \(\pi\) by contributing with investigation and evidence from foreign jurisdictions. The lack of international collaboration can, on the contrary, reduce the size of \(\pi\) by being uncooperative, slow and impeded by low competence. The direction of foreign influence on \(\pi\) is thus not given, and can both increase or decrease the size of \(\pi\).

Faced with a settlement offer from the prosecutor, the two types of defendants will either choose the same strategy, subscripted p, or choose different strategies, subscripted s. The model includes only the game that happens after the defendant is apprehended and the case is investigated. Thus, the sequence of the game is that at time t=0 the defendant knows its guilt, and the prosecutor knows the strength of the case. At time t=1 the prosecutor acts on her private information and decides to either drop the case, make a settlement offer, or bring the case to court. Based on the action taken by the prosecutor, the defendant can update its information based on information the defendant believes the prosecutor reveals based on her action in t=1.

A defendant found guilty in court will expect to suffer a fine x, imposed on the defendant by the court.Footnote 6 If the case concludes with a settlement, the prosecutor offers to allow the defendant to pay a fine a, which includes the expected associated costs for the defendant.Footnote 7 Because a guilty defendant faces a higher probability of a guilty verdict than does an innocent defendant, expressed as \(\pi _i<\pi _g\), the guilty defendant faces a higher expected sanction if the case goes to trial: \(\pi _i x<\pi _g x\). Implicitly, a guilty defendant is inclined to accept a higher settlement sanction, a, than an innocent defendant, noted \(a_i<a_g\). With k being the defendant’s cost of going to court, the defendant’s condition for accepting a settlement proposal is \(a_t <\pi _t x_t +k\).Footnote 8 An innocent defendant will accept any settlement offer where \(a\in [0,a_i]\), while a guilty defendant will accept a settlement offer where \(a\in [0,a_g]\). \(a_i\) and \(a_g\) is thus the threshold sanction for the innocent and guilty defendant respectively.

The social cost of trial (regardless of defendant’s guilt) is a cost, C, and this cost is a concern for the prosecutor when deciding whether to offer a settlement or bring the case to court.Footnote 9 The prosecutor’s decision about the case depends also on her concern about the risk of sanctioning an innocent defendant (noted \(\lambda\), a type 1 error) versus the problem of not sanctioning a guilty defendant (noted \(\gamma\), a type 2 error). Hence, a court sanction x or a settlement sanction a yields a positive utility \(\gamma x\) (\(\gamma a\)) for the prosecutor when the defendant is clearly guilty. A sanction x or a imposed on a defendant who could very well be innocent implies a negative utility \(\lambda x\) (\(\lambda a\)) for the prosecutor. We will return to the implication of this assumption.

3.2 The prosecutor’s objective

The prosecutor tries to maximize her utility by weighing her aversion to sentencing an innocent defendant against her desire to punish a guilty defendant, while keeping in mind the cost to society if the case goes to court. We assume that the prosecutor’s perceptions in these respects correspond to those of society.Footnote 10 Her decision regarding the case depends on the extent of her discretionary authority, as mentioned: limited discretion requires her to offer the same sanction to defendants who committed the same crime, while broad discretionary authority allows her to make different settlement offers in equivalent cases. For now, we consider the case of limited discretionary authority.

Given a prosecutor with limited discretion who makes a pooling offer, \(a\le a_i\), which both the innocent and guilty defendant will accept because the proposed sanction is lower than the threshold sanction for either of the two defendant types.Footnote 11 The prosecutor’s utility (PU) when making a pooling offer, subscripted p, will be

The expression includes the positive utility of sanctioning a guilty defendant minus the negative utility of sanctioning an innocent defendant. This net utility increases with the size of the proposed sanction because the prosecutor has to offer the same sanction to any defendant, regardless of guilt. The value \(\pi\) that maximizes PU depends on the sign of the bracket term \([\pi \gamma -(1-\pi )\lambda ]\). This term is negative if \(\pi <\frac{\lambda }{\gamma +\lambda }\) and positive if \(\pi >\frac{\lambda }{\gamma +\lambda }\). If the term is positive, the optimal offer from the prosecutor is \(a=a_i\) which both defendants accept. If the term is negative the optimal offer is \(a=0\), and the case is dropped.Footnote 12

Consider now the circumstance where the prosecutor makes a separating offer \(a_t\in [a_i;a_g]\), subscripted s. Now, a guilty defendant will accept the offer while an innocent defendant declines. The prosecutor’s utility is then

The difference in utility influences the prosecutor’s preference for a pooling p or separating s offer, \(PU_s-PU_p\), which depends on how the prosecutor values sanctioning an innocent versus not sanctioning a guilty defendant, represented by the bracket term \(\frac{\lambda }{\gamma +\lambda }\).

In summary, when \(\pi >\frac{\lambda }{\gamma +\lambda }\) the strength of the case will always make it preferable for the prosecutor to offer a higher settlement offer as the expected benefit of punishing a guilty outweighs the expected cost of punishing an innocent. The optimal pooling offer is then \(a=a_i\), and the prosecutor’s optimal separating offer is \(a_g\).

When \(\pi <\frac{\lambda }{\gamma +\lambda }\) the portion of guilty defendants is so low that the cost of incorrectly sanctioning innocent defendants does not outweigh the benefit of sanctioning the guilty defendants. The optimal pooling offer will therefore be \(a=0\) and the optimal separating offer is \(a=a_g\).

3.3 The defendant’s objective

The defendant will accept a settlement offer if the proposed sanction is lower than the expected cost of going to court: \(a_t<\pi _t x+k\). If considering \(\rho _i=[0;1]\) the probability that the defendant in question will accept a settlement offer, the defendant’s utility (DU) function is

Since a case against an innocent defendant is weaker than a case against a guilty defendant, \(\pi _i<\pi _g\), the prosecutor has to offer a sanction that implies a bigger sanction gap \(x-a\) to account for the weaker case.Footnote 13 When the case is sufficiently weak (when \(\pi\) is sufficiently low), the settlement offer a will be small enough to persuade an innocent defendant to accept a settlement rather than claiming his innocence in court.

A guilty defendant knows the prosecutor will have a strong case if it is brought to court, and therefore the sanction gap does not have to be large for the guilty defendant to accept the settlement offer. Hence, the settlement offer in this scenario is closer to what the expected sentence at court will be. However, the guilty party has less to gain from accepting the settlement compared with a court case, since in court there is a chance of being acquitted, and if that happens, the only downside is the cost of court proceedings k (which can be substantial).

Take into account the fact that the defendant is a corporation there is a clearer risk of collateral damage if it is found guilty.Footnote 14 We add c to the defendant’s equation, an amount that is strictly positive and occurs with a probability \(\theta\), and study the implication of the possible added cost of collateral damages.Footnote 15 When the defendant is a corporation, we consider “the corporation’s utility” to reflect the aggregate utility functions of the corporation and its stakeholders.Footnote 16

The defendant’s decision to accept a settlement offer depends on the trade-off between the expected cost of the sanction offered by the settlement a with full certainty about the costs, and the expected sanction if found guilty in court x imposed with probability \(\pi\). Based on the analysis above regarding the influence of the level of prosecutorial discretion on the defendant’s outcome, we make the following proposition.

Proposition 1

When exceeding a certain size, the sanction gap, \(x-a\), determines the defendant’s willingness to accept a settlement proposal, regardless of guilt.

From \(a=\pi x+k\) we know that \(x=\frac{a-k}{\pi }\). When the defendant faces a strong case (high \(\pi\)), the sanction gap is smaller. When the case is weaker, with a lower value of \(\pi\), the sanction gap increases. We know already that an innocent defendant will face a lower value of \(\pi\) than a guilty defendant. Guilt becomes less relevant for the defendant when deciding to accept or reject a settlement offer, as the gap between the sanction in court and the proposed settlement sanction is too large. Factors that increase the sanction gap include reduced sanction for self-reporting and/or cooperation, a weaker obligation for the prosecutor to verify the facts of the case, including the matter of ’corporate guilt’, less information available for public scrutiny, and, for the corporate defendant, a risk of substantial collateral consequences. These factors increase the sanction gap, and may lead innocent offenders to accept a settlement, even under circumstances when the settlement penalty exceeds the expected penalty in court.

Proposition 2

The broader the discretionary authority for the prosecutor, the larger the expected sanctions gap, and the higher is the likelihood that an innocent defendant accepts an offered settlement penalty.

When the prosecutor enjoys broad discretion, she can apply a broader range of sanctions. The prosecutor can act more leniently towards defendants that face a weaker case (low \(\pi\)) which expands the expected sanction gap. By contrast, a prosecutor with limited discretion has to offer the same sanction to defendants charged with the same crime, irrespective of the strength of the case. The theory shows that the defendant with limited discretion prefers a settlement when the case is of a certain strength (\(\pi >\frac{\lambda }{\gamma +\lambda }\)). Considering the constraints of the prosecutor with limited sanction options, and the utility preferences when her discretion is limited, the expected sanction gap becomes smaller when the prosecutor enjoys broad discretion.

In addition, when the prosecutor has broad discretion, she can offer more complex settlement contracts (like N/DPA’s) to evade the question of guilt. This places the prosecutor in a far better position for influencing the size of c, the collateral damages. Also, the risk of accumulating significant collateral damages is different for a defendant that is a firm rather than an individual. We know that for a corporate defendant to accept a settlement offer, \(a<\pi x+k\). For the defendant, the collateral damages c may be greater than the expected sanction from the court case or the settlement, and occurs with a probability \(\theta\).

The collateral claims may increase the sanction gap between the total sanction in court, \(\pi x+k+\theta c\), and the proposed settlement a. In result, a defendant accepts a settlement offer that is higher than the expected sanction in court. If the defendant is risk averse (or unable to accept risk because of a certain market or financial situation), the perceived consequences are inflated as if the probabilities are higher than they actually are. For the defendant, this means it is inclined to accept a settlement for a higher probability of being found innocent in court, or, a higher settlement penalty.

3.4 Results and implications

In our version of the theory, with a focus on corporate bribery cases, we introduce uncertainty around the defendant’s private information. Implicitly, the level of \(\pi\) might be uncertain for both the prosecutor and the defendant, and low even if the defendant is guilty. A large \(\pi\) combined with a low x is a very different circumstance than a small \(\pi\) and a very high x that could potentially bankrupt the defendant. Uncertainty, combined with a wide range of possible sanctions in court and thus a risk of incurring a severe penalty, implies that the defendant has a strong incentive to accept a settlement even if the facts of the case would not fulfill the burden of proof required by a court (meaning a large \(\pi\)).Footnote 17

By adding nuance to the assumptions about the private information of the defendant, the theory helps us understand when a corporate defendant will accept a settlement offer even if there is a substantial chance to be acquitted in court. When the defendant is a corporation there may be circumstances where the prosecutor, who cooperates with prosecutors in other countries, knows more about the defendant’s guilt than the defendant itself knows. For example because the firm’s management and lawyers, who represent the firm, were not part of the committed crime. If the acts were carried out by an agent on behalf of the accused firm in a foreign country, the management team - despite their internal investigations - may have incomplete information about the facts of the case, and thus about the extent of their firm’s “guilt” . On the other hand, the defendant may influence the strength of the case (\(\pi\)) for example by engaging clever lawyers. Such resources may benefit the firm in the investigation phase, the negotiating stage of the settlement, or in court. Successful international cooperation may strengthen the case and increase \(\pi\). However, as such efforts are time- and resource consuming, it may give a defendant with sufficient resources space to complicate the apprehension of evidence and thus reduce the strength of the case.

The stronger the case (the closer \(\pi\) is to 1), the smaller the settlement discount will have to be for the defendant to choose the settlement option. This choice does not depend only on the value of \(\pi\); the size of x will be equally important. The larger the sanction gap, \(x-a\), the stronger the incentive for an innocent defendant to accept a settlement sanction, which also implies, the more likely it is to determine the enforcement outcome than actual responsibility for crime. Any added uncertainty regarding the defendant’s guilt will result in a reduction of the sanction gap threshold at which the defendant will accept a settlement. A defendant that is a corporation may be likely to accept a settlement with a smaller sanction gap than what an individual would accept, because there is greater uncertainty regarding a corporation’s ’guilt’.Footnote 18

Limited transparency in legal practice influences the defendant’s decision to accept a settlement or not, and if the expression of a general trend, it can have system-wide effects on the predictability of the enforcement system. Remember that a defendant accepts a settlement offer \(a=[0;a_t]\) when he is certain about his type (guilty or innocent). When the defendant is a corporation, and less certain about its type, the corresponding uncertainty will influence the probability of a decision to settle \(\rho\), in our model an exogenous given probability. The strength of the case \(\pi\) and the size of the fine x depend on the prosecutors’ understanding of and experience with the law. In jurisdictions where settlements are not published, law enforcers have little case law to rely on for guidance. Firms and individuals base their understanding of the law on publicly available information. Absence of such information may increase the use of settlements, because defendants choose to accept a settlement caused by the uncertainty of legal practice.Footnote 19 In jurisdictions without judicial review of settlements, the prosecutor has broad freedoms when applying the law (Søreide and Vagle 2020). If that means the proportionality between the offense and the sanction becomes more blurred, it easily reduces the predictability across cases, and this is especially a problem when there is little public information about the cases and enforcement outcomes. In common law countries, and to some extent civil law countries, where the holdings in tried cases contribute to the development of the law, having few cases go to trial can be detrimental to the development of the law. More explicit regulations might make up for some of the uncertainty that the lack of case law create. As we show in the model, it is less likely that strong cases (high \(\pi\)) go to court. Thus, we are left with a situation where only the weak cases are tried in court, and the reverse of the maxim of “hard cases make bad law” become true, as we get “weak cases make bad law”. If the heightened uncertainty associated with enforcement increases defendants’ inclination to accept settlements, this theory shows, the use of settlements easily becomes self-escalating: in other words, more use of settlements will increase the use of settlements.Footnote 20

In addition to considering the strength of the case when deciding which segment of the sanction range to apply, the prosecutor will evaluate the consequences imposed on the defendant, including potential collateral damage. Both c and \(\theta\) are of unknown sizes, and the interpretation of the size of these variables can be influenced by both parties. The understanding of the probability \(\theta\) of collateral damage can be artificially inflated by the defendant, making the prosecutor more prone to choose a settlement than a guilty plea or a court case.Footnote 21 For example, if a firm that relies heavily on government contracts risks debarment from public procurement, the defendant may succeed in convincing the prosecutor that the ensuing debarment will have unreasonable large consequences for the firm and society. The risk of debarment creates an artificially large sanction gap that may lure prosecutors to offer a settlement, instead of bringing the case to court.Footnote 22

In the model we address how the prosecutor is influenced by her moral cost, noted \(\frac{\lambda }{\gamma +\lambda }\). The prosecutor’s moral cost, combined with the prosecutor’s degree of discretion, influences her settlement offer, which in turn influences the size of the sanction gap, and the defendant’s willingness to accept the settlement proposal. From the bracket term \(\gamma\) is the utility of sanctioning a guilty defendant, and \(\lambda\) the negative utility of sanctioning an innocent defendant. If the value of \(\lambda\) is low and the prosecutor has limited discretion, the prosecutor can only offer the same sanction to defendants who have committed the same crime, at the bottom of the sanction scale. The value of \(\lambda\) therefore determines whether a prosecutor with limited discretion will apply the same sanction spectre as the prosecutor with full discretion. As \(\lambda\) increases, the negative utility of sanctioning an innocent defendant increases. Because of this, the prosecutor will have to increase the proposed sanction in order to reduce the chances of sanctioning an innocent defendant. We remember that the prosecutor who enjoys full discretion can tailor the proposed settlement to each defendant. Another effect of low values of \(\lambda\) is that the level of \(\pi\) required for the prosecutor to consider sanctioning a defendant is lower, meaning that the prosecutor with a low \(\lambda\) is willing to sanction a defendant with lower quality of evidence.

Finally, a public prosecutor is subject to a budget constraint, which induces the prosecutor to consider the marginal utility of the alternative enforcement modes, i.e. settlement or trial, with respect to their ability to deliver the intended social benefits, such as crime deterrence. For a given budget, the prosecutor will maximize enforcement by allocating resources in a manner that allows the marginal utility of the two enforcement modes to be the same. The optimal combination of settlement and trials will depend on the marginal impacts of the two enforcement modes, respectively, which is unknown. Even if settlement is less costly per case than trials, it is not necessarily the favoured enforcement mode. For example, the two options may be found similar in terms of marginal utility per euro spent if court proceedings are perceived to be many times as effective in terms of deterrence.

4 Legal analysis

Regulation of corporate bribery is largely a result of cooperation through international institutions like the OECD, the World Bank, the United Nations, and the European Union. Their conventions have resulted in a more harmonized legal framework than what was available until the late 1990s. Corruption is now criminalized across the globe, and many countries include bribery carried out abroad in their penal codes. Substantial variation in enforcement practices and in the specific legal requirements for liability limits the de facto harmonization of the rules, and this is especially the case for corporate liability. In this section we substantiate the analysis presented above by reviewing current regulations on corporate liability in bribery cases, and we investigate the extent to which enforcement practices support our theoretical claims. We describe the prosecutor’s legal space for offering settlements in the United States and the United Kingdom and explore corporate offenders’ incentives to accept a settlement in circumstances where there are doubts about the evidence against them.

The economic analysis suggests that the greater the expected sanction gap, the higher the penalty a defendant will be willing to pay to avoid trial. Even innocent defendants are inclined to accept a sanction that ends the case if the consequences of going to court are both substantial and unpredictable. Our findings suggest that when the defendant is a corporation, the uncertainty about guilt and the risk of substantial collateral damage will further increase the defendant’s inclination to accept a settlement. In fact, an innocent defendant may well accept a settlement penalty that significantly exceeds the expected sanction by a court if the indirect consequences of a court case are substantial. What we seek now is to study factors that determine the expected sanction gap, considering what we know about expected sanctions, the predictability of the enforcement system, and the rule of law.Footnote 23 The prosecutor’s extent of discretion is critical in this respect, because as shown, it affects the enforcement system’s predictability and thus the corporate offender’s decision to accept or decline a settlement.

If the legal system is too rigid, the prosecutor is left with very limited tools when trying to combat complex corporate crime. Corporate bribery cases are often so complicated that it is impossible to tailor a legal system to cope with these types of crime without a certain degree of discretion. Neither the prosecutor nor the defendant desires a legal framework that is too rigid or too flexible.

4.1 Regulation and enforcement in the United States

We begin with a brief presentation of the relevant legal framework and enforcement practices in the United States, focusing on the factors that define the sanction gap.

4.1.1 Corporate liability in bribery cases

The United States regulation of corporate liability in bribery cases is characterized by broadly defined corporate criminal liability, extensive use of negotiated settlements, and a range of laws that provide prosecutors with extensive authority (Arlen and Buell 2020). Companies can be held vicariously liable for crimes committed by their employees,Footnote 24 including for bribery. US bribery enforcement is harmonized with international conventions such as the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) and the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention.Footnote 25

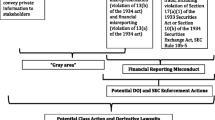

The United States practices three forms of settlements, plea bargain, DPA and NPA. A plea agreement is considered a settlement with conviction, while Non-Prosecution Agreements (NPA) and Deferred Prosecution Agreements (DPA) are considered without conviction.Footnote 26 When the settlement does not require a guilty plea, the risk of other jurisdictions pursuing the same case increases if the question of blameworthiness is not sufficiently addressed by the settlement process. This is a risk associated with N/DPAs, which can potentially increase the total sanction if sanctions from other jurisdictions are “piled on” the initial settlement accepted by the defendant (Pieth 2020; Oded 2020).

Efficient enforcement is not a result of corporate criminal liability alone. A range of background laws, as described by Arlen and Buell (2020), bolster the position of the prosecutor vis-à-vis the defendant and facilitate enforcement in corporate bribery cases. Laws regulating attorney-client privilege, protections against self-incrimination, and accounting provisions supplement the tools available to the prosecutor who is building a case against a corporation. Such sorts of regulation increase prosecutors’ ability to secure evidence and cooperation from the alleged corporate offender and ease the US enforcement of corporate criminal liability.

4.1.2 Enforcement practices

In the period 2005 to 2018, the United States enforced its corporate bribery regulations in a higher number of cases than all other countries combined.Footnote 27 US prosecutors have brought 263 enforcement actions against bribery of foreign officials, and 65 percent of these cases are toward US firms or US nationals (TRACE 2019). Between 1992 and 2019, no corporate bribery case ended in a trial conviction in the United States (Alexander and Cohen 2015; Garrett 2014). They were concluded instead by negotiated settlements, which means, in most cases, that the assumption of an independent party - a judge - in place to evaluate wrongdoing does not apply. In practice, the prosecutor is responsible for investigation, for proposing a sanction, and for enforcing the agreed sanction.

In cataloging and analyzing the results of 486 settlementsFootnote 28 between publicly listed companies and the US Department of Justice in the period 2003-2011, Alexander and Cohen (2015) and Garrett (2014) find that there was a steady increase in the use of settlements. They also find a shift toward the resolution of cases through settlements like N/DPAs rather than through guilty pleas. Agreements with a confession (plea agreement) used to be the predominant form of settlement, but agreements without confession (N/DPAs) made up an increasing share of settlements after 2005 - after which we also saw bribery cases and antitrust becoming the most prominent settlement crime categories. Enforcement data in the United States are now more readily available and show that the number of settlements stabilized in 2011 at 25 to 40 cases per year. Despite memos guiding the use of settlements and judiciary review (apart from NPAs), the increasing use of settlements has implied expanded discretionary authority for prosecutors.Footnote 29

US prosecutors use the United States Sentencing Guidelines (USSG) to determine the range of sanctions applicable to a specific crime. The prosecutor applies a formula specified in the USSG to reveal the expected sanction range that would apply if the case were to go to court. The prosecutor can then offer sanction discounts that the defendant would receive as part of accepting the settlement.

To illustrate the potential size of the sanction gap, we provide an example from the Panasonic Avionics Corporation (PAC) case.Footnote 30 Table 1 shows the offense level calculation, based on a table in the USSG. This is used to calculate a base fine; in this example, the base fine is $122,681,975.Footnote 31 A multiplier is applied to the base fine to produce a range of fines that the defendant can expect if the case goes to court (Table 2). Finally, the prosecutor calculates a culpability score, awarding the firm in this case a 20 percent discount because it fully cooperated in the investigation.

The fine that PAC agreed to pay was $137,403,812, which was 20 percent below the minimum fine and 60 percent below the maximum fine, given the stipulated sanction range. PAC also paid $143 million in disgorgement to the SEC.Footnote 32 The total fine paid amounted to more than $280 million. Even so, it was below what economic theory postulates is necessary to deter bribery, given the size of contracts PAC secured through bribery. In this case, the fine is similar in size to the $275 million that PAC paid to sales agents in the Middle East and Asia for the sake of securing contracts between 2007 and 2017. From the published settlement we know that PAC’s agents usually get 6 to 10 percent of the net contract amount.Footnote 33

The highest possible sanction from the example above does not include the cost of trial and possible collateral claims. To reach the actual total cost if PAC were to decline the settlement offer, estimates of the cost of trial and collateral damage have to be added (remember k and c from the theory section). If these costs are added, the sanction gap widens, and the defendant’s option of choosing to decline a court case becomes not a real choice but an illusion.

4.1.3 Indicators of a sanction gap in the United States

As a common law country, the United States relies on guidance from the Department of Justice for direction of enforcement practices. This guidance will often take the form of a memorandum. The Thompson memo of January 20, 2003, now incorporated into the Justice Manual, introduced the option of settlements in cases where the defendant cooperates, or where a settlement is in the interest of the general public, referring to the general guidelines for NPAs.Footnote 34 There is, however, no guidance that clarifies when a DPA is appropriate (Levy 2011).

The Justice Manual emphasizes self-reporting as one of the aims of N/DPAs, and in fact self-reporting and cooperation are required to be eligible for an N/DPA.Footnote 35 However, given that all corporate bribery cases in the United States are settled through an N/DPA, self-reporting and, especially, cooperation appear to be broadly defined. The incentive for a firm to cooperate is the option of receiving a reduced sanction, faster conclusion of the case, and more predictability. A firm that cooperates but did not self-report can get up to a 25 percent reduction of the intended sanction, increasing to as much as a 50 percent reduction if the firm both cooperates and self-reports. This reduction further increases the sanction gap between the expected sanction in court and the proposed settlement. Given United States enforcement practices and use of N/DPAs, the maximum sanction imposed through a settlement cannot exceed the maximum sanction available in court.

The United States is among the OECD countries that grant their prosecutors high degree of discretionary authority. Søreide and Vagle (2020) examine the extent of discretion available to the prosecutors in 66 countries.Footnote 36 As more FCPA cases are brought by the SEC and DOJ, however, the guidelines for US prosecutors develop in greater detail, which has decreased the prosecutor’s discretion. Guidelines, such as the United States Justice Manual, increases the predictability of the legal process of N/DPAs.

The court system in the United States has characteristics that are associated with uncertain predictability with respect to both process and expected sanction.Footnote 37 The debated outcome of a jury process affects the predictability of a court case in the United States (Davis 2019). The greater procedural predictability of N/DPAs together with a lack of predictability in US courts and potential collateral claims makes a settlement the only viable option for a firm when this option is granted to them by US law enforcement. The United States publishes summaries of settlement agreements online and performs well in that respect, according to the OECD Working Group on Bribery (OECD 2016).

4.2 Regulation and enforcement in the United Kingdom

The legal framework for corporate liability and enforcement of bribery cases in the United Kingdom is inspired by US regulations, but there are important differences with respect to both regulation and enforcement practice. The United States has both NPAs and DPAs, while the United Kingdom only uses a form of DPA.

4.2.1 Corporate liability and enforcement in bribery cases

The United Kingdom, like the United States, forbids bribery, and to a certain extent holds corporations liable for actions committed by individuals acting on behalf of the firm.Footnote 38 The Bribery Act 2010 criminalizes illegal practices and is harmonized with international conventions.Footnote 39 The Serious Fraud Office is mandated to investigate and prosecute corporate bribery cases in the United Kingdom.Footnote 40 When the prosecutor considers prosecution, it must fulfill a two-stage test required by the Code for Crown Prosecutors, comprising the evidence stage and the public interest stage. A settlement with conviction is organized in the United Kingdom through a guilty plea. By comparison with the United States, in the United Kingdom the court is much more involved in the decision to impose a settlement, which is an effort to protect the public interest. Through a guilty plea, the defendant pleads guilty to some or all of the charges raised by the prosecutor. The defendant can also settle with the prosecutor on an appropriate sentence range. While the UK generally adheres to the identification doctrine, Section 7 of the UK Bribery Act 2010 introduces an exception (OECD 2016). However, UK courts reject that crimes committed by a lower level employee can be attributed to the firm. For corporate criminal liability to apply, the crime has to involve senior management (Arlen 2020).

The United Kingdom practices settlements without conviction through a DPA (OECD 2016).Footnote 41 The United Kingdom Crime and Courts Act 2013 requires the director of the Serious Fraud Office (SFO) and director of the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) to publish a guideline on how to interpret the application of DPAs. This guideline is the Deferred Prosecution Agreements Code of Practice (DPA Code). The process toward a settlement has two initial steps. Given sufficient evidence to fulfill the evidence stage, the director of the SFO or the CPS considers whether it is in the public interest to enter into a DPA instead of bringing a regular court case or, alternatively, dismissing the case. If the public interest test is met, the SFO and CPS directors are only two prosecutors who can enter into a DPA, according to the Code. The defendant cannot demand a DPA; it is at the prosecutor’s discretion to invite a defendant into a negotiation, and when a defendant is invited to negotiate, there is no guarantee that a DPA will be offered (see the DPA Code). The DPA Code recommends not entering into a DPA if the firm is a repeat offender, if the conduct is part of its established business practice, or if the compliance program was obviously inefficient.Footnote 42 The guidelines give a fairly detailed description of the aspects to be considered, but the interpretation of how these aspects should be weighed - for example, how much cooperation is required for cooperation to be deemed sufficient - is not determined by the DPA Code.

A DPA can only be offered to firms, it cannot be offered to individuals. If accepting a settlement means that individuals risk a separate enforcement process for the crime imputed to the corporation, this may reduce the corporate defendant’s inclination to accept a settlement. So far, however, no individual has been charged after the firm he or she represents has agreed to a DPA, despite the fact that ultimately, corruption stems from decisions made by individuals Gorsira et al. (2021). Compared to a court case, a settlement leaves less information available to the public, the prosecutor, and other judges. Over time, the limited availability of case law results in less predictability and offers less guidance to prosecutors and judges unfamiliar with corporate bribery cases.

As of 2019, the United Kingdom has brought a total of 37 enforcement cases concerning bribery of foreign officials. This is the second-highest number worldwide (the United States has seven times more cases) (TRACE 2019). Of the UK enforcement actions conducted, nine cases concluded with a DPA.Footnote 43 The SFO’s settlement with Rolls-Royce is a recent example of enforcement practice in the United Kingdom. Under British law, firms are required to self-report and cooperate in order to be awarded a DPA and in order to be eligible for a reduced sanction.Footnote 44 Rolls-Royce did not self-report, but they were nonetheless offered a DPA and their sanction was reduced. This contradicts the criteria stated in the legal framework of the DPA for the United Kingdom.Footnote 45 The reason why Rolls-Royce still got the reduced sanction was that once the SFO started the investigation, the firm exposed evidence of other crimes to the SFO. The SFO concluded that they would not have been able to obtain this information had Rolls-Royce not handed it over to them. For that reason, the firm was given a reduced sanction. The SFO thus signaled that corporate offenders still can obtain a reduced sanction if they cooperate beyond the part of the crime that the SFO exposes.

4.2.2 Indicators of a sanction gap in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom has introduced settlements as DPAs (OECD 2017). Settlements are regulated by the Crime and Courts Act 2013, but as the United Kingdom is a common law country, the practical implications of the settlement will be determined though precedence and case law. Details about the DPAs are made publicly available as long as they do not interfere with an ongoing investigation.Footnote 46

The United Kingdom sentencing guidelines for corporate bribery allow for unlimited monetary sanction.Footnote 47 When establishing the harm, represented by a financial sum, the UK sentencing guidelines use “the gross profit from the contract obtained, retained or sought as a result of the offending” or “the likely cost avoided by failing to put in place appropriate measures to prevent bribery.” If the harm is difficult to establish, the court may use general revenue as a starting point and consider 10-20 percent of the revenue as an estimate of the amount achieved from the offense. In large fraud or bribery cases like the Libor case,Footnote 48 other measures of harm may be justified.Footnote 49 The sentencing guidelines give the court some guidance on how to establish harm, but the amount of discretion is large, which influence the expected sanction gap.

Corporate bribery often involves several jurisdictions. If the defendant risks sanctions in more than one country, the sanction gap can further increase. DPAs are encouraged in the United Kingdom in order to take into account enforcement actions in other countries.Footnote 50 The intention is to prevent the piling on of sanctions, which can happen when different jurisdictions, or different prosecuting authorities within the same jurisdiction, add sanctions for the same crime on top of the already awarded sanction. The prospect of this happening may act as a disincentive that keeps firms from opting to self-report and cooperate. Alternatively, the piled on sanctions can serve to augment fines that are initially too small to have a deterrent effect. What matters for the defendant is the total amount of sanctions imposed.Footnote 51 In addition to the potential piling on, the defendant also risks collateral claims, and the UK prosecutor is instructed to take these into account when weighing the option of a DPA.Footnote 52 A key aspect of settlements without a guilty plea is that firms can avoid collateral claims.

When determining the sanction, the court is instructed to assess the sanction against three objectives, namely the “removal of all gain, appropriate additional punishment, and deterrence.”Footnote 53 Under the United Kingdom’s Bribery Act, a company charged with section 1, 2, 6, or 7 is subject to an unlimited fine.Footnote 54 Through a DPA the defendant can receive a reduction of up to one-third for an early guilty plea.Footnote 55

5 Results and Discussion

We started by investigating mechanisms that influence the actions of both the prosecutor and the defendant in a settlement process for corporate bribery. We showed why the structure of the process largely determines the law enforcement outcome. Following this review of enforcement practices, we will now discuss the empirical underpinning of our propositions.

According to theory, the size of the difference between the expected sanction in court and the proposed settlement sanction, the sanction gap, determines a defendant’s inclination to accept a settlement offer. Our legal analysis shows that a defendant in the United States hardly ever will decline the prosecutor’s settlement offer if declining implies court proceedings. This is partly because the settlement offer is, as a rule, at least 25 percent lower than the lowest point of the sanction range for the specific crime, and partly because of the magnitude of additional consequences that might follow a verdict. Under these circumstances the option of criminal trial becomes an illusion, and not a real choice.

This finding supports our first proposition: if a corporate defendant will accept a settlement when the expected sanction in court exceeds a certain level, it will also do so when a court verdict involves the risk of substantial collateral damage, which increases the de facto sanction gap. When the expected collateral damage exceeds a certain level, the defendant becomes inclined to accept a proposed settlement sanction even if it is higher than the expected sanction in court. A number of factors work together to create the large sanction gap in the United States, including the opportunity to settle without pleading guilty, broad prosecutorial discretion, absence of judicial review, comprehensive background law, and a wide sanction range in court. The sanction gap in the United Kingdom is smaller, as shown by our legal review, and so there is more uncertainty as to whether a firm will accept or decline a settlement offer. Factors that limit the sanction gap in the United Kingdom include limited prosecutorial discretion, the presence of judicial review, the compliance defense, and a more limited sanction range in court.

We also find support for our second proposition, which claims that broader prosecutorial discretion increases the sanction gap, and increases the likelihood of innocent defendants accepting an offered settlement penalty. When evaluating the consequences between sentencing an innocent defendant versus not sentencing a guilty defendant, the prosecutor with limited discretion, who also does not want an unfair outcome, considers the potential additional consequences for the corporate offender if sentenced in court. However, the burden of an unfair outcome decreases if the prosecutor can end the case without having to determine the defendant’s guilt. In some jurisdictions, including the United Stated and the United Kingdom, there is no need to treat the question of someone’s guilt as part of an N/DPA. That means the prosecutor largely avoids the concern about sentencing an innocent defendant or not sentencing a guilty defendant. With less reason to worry about the risk of not punishing a guilty firm, it becomes easier for the prosecutor to offer lenient treatment. This lenient treatment can allow for indirect consequences of a potential verdict to influence the offered settlement.

In our version of the theory, we introduce an inherent attribute of the “corporation’s guilt,” which reflects the strength of the case: the actual basis for liability will be uncertain not only for the prosecutor, but also for the defendant. This distinguishes the individual defendant from the corporate defendant, and supports our second proposition. The option of offering a settlement allows the prosecutor to spend fewer resources on investigation for the sake of establishing the material truth of the case, which means that by offering more lenient treatment, the prosecutor can complete the case with less knowledge about the facts, and thus the strength of the case. Therefore, it can be optimal for the prosecutor to investigate just enough to conclude a settlement, and still, less than what is needed to determine the exact responsibility of the crime. The legal analysis supports this claim, as prosecutors in both the United States and the United Kingdom tend to offer more lenient treatment than what is stipulated as stated goals of their law enforcement system.Footnote 56

Beyond the support of results presented in the theory section of the paper, the legal review reveals some related enforcement patterns. First, enforcement through the use of settlement is rarely consistent with economic results on deterrence of corporate crime, partly because the aim of deterrence is difficult to combine with the aim of promoting self-reporting, and partly because prosecutors might take into account other non-legal aspects (such as “the public good,” which could reflect employment or other market-related concerns). The contradiction between aims is seen, for example, when one compares the United Kingdom sentencing guidelines and the sanctions imposed on firms through a DPA. Whereas the guidelines instruct the court to remove all gain from the crime and add an appropriate additional punishment, in line with the aim of crime deterrence, the reduced sanction offered under a DPA tends to be far too lenient to accomplish the goal of crime deterrence, as seen in the Sarclad case.Footnote 57 Another case, the one against Rolls-Royce, illustrates the prosecutor’s inclination toward lenient treatment. The defendant did not self-report its offenses, yet it received substantial credit for cooperation after the SFO had started its investigations.Footnote 58 Both examples show a wide gap between the sanctions expected in court and the sanctions received through a DPA.

Enforcement practices in the United States are better aligned with crime deterrence because the sanctions are more severe and the benefits for cooperation more predictable (Arlen 2020). On the other hand, in countries where courts tend to impose a low level of sanctions on corporate offenders, a firm generally has little incentive to accept a settlement that is similar in size to the expected outcome in court if it has some chance of being acquitted in court. When the chance of acquittal is low, predictable lenient treatment for those who self-report secures a solid enforcement statistic because a number of factors make self-reporting prudent even if the offender found crime rational before committing the offence. Nonetheless, lenient enforcement through settlement will not necessarily deter corporate bribery.Footnote 59 Reduced penalty for those who self-report and cooperate may well be consistent with deterrence. The problem is the level of benchmark penalties, that is, the level from which the penalty is reduced. Too often, this level is too low for deterrence, but this is a problem in cases concluded in court as well. The reason why settlement might water down deterrence is primarily the offenders’ perception that penalties are negotiable (combined with the fact that they are). If governments offer ’bigger carrots’ (in the sense of larger penalty reductions) than the defendant deserves, given the extent of cooperation in law enforcement, the sanction loses its strength in terms of crime deterrence. However, to some extent, attributes of settlement-based enforcement may reduce this concern. Transparency of the facts of the case and reduced penalty upon cooperation are signals to other firms, not only about wrongdoing, but also the benefit of corporate compliance and self-reporting.

Second, we find that the extent of discretionary authority granted to prosecutors varies significantly across the countries reviewed by the IBA survey (Makinwa and Søreide 2018). The United States provide broad discretion to their prosecutors, while the United Kingdom is more restrictive in this respect. Broad discretionary authority enables the prosecutor to tailor the proposed sanction to what she assumes is the defendant’s acceptable sanction level. This makes it easier for the prosecutor to induce the defendant to accept a settlement instead of having the case go to court. In addition, discretionary authority is decisive for the prosecutor’s opportunity to exploit the whole sanction range, allowing her to offer a far more lenient sanction than what would be expected in a court case.

6 Conclusion

We analyze how the difference between the expected sanction in court and the proposed settlement offer –that is, the sanction gap –influences the prosecutor and the defendant in their positions toward settlement as an enforcement outcome of a corporate bribery case. In contrast to former theory on the use of settlement, ours considers the defendant as a firm and not an individual, which leads to different results regarding the defendant’s choices vis-à-vis a law enforcement institution.

Especially, we explain why the sanctions gap, which determines the outcome of the enforcement process, is categorically different for corporate and individual defendants. Despite better access to legal expertise, corporations are no less exposed to the risk of unfair enforcement results. We show why there might be an extreme imbalance between the expected cost associated with settlement and trial, respectively, which in the end, weakens the rule of law. We also find that the prosecutor has an incentive to offer a lenient settlement if doing so reduces her duty to ascertain the material facts of the case.

The prosecutor’s discretion to influence the application and content of the settlement offer influences the defendant’s incentive to accept or reject a proposed settlement. Broader prosecutorial discretion increases the sanction gap, as the prosecutor will have more options to tailor the proposed sanction to the specific defendant. If the defendant can avoid pleading guilty but still receives a settlement offer, the sanction gap increases, as the defendant can avoid collateral claims. Upon the theoretical analysis, we reviewed legal regulations and enforcement practices in the United Kingdom and the United States. This help explain why a defendant may accept a settlement sanction that exceeds the expected sanction in court, regardless of actual responsibility, if there is a realistic threat that a guilty verdict will lead to substantial collateral damage to the firm.

Settlements in the United States and the United Kingdom have many of the same attributes, but so far, there are few cases available for review in the United Kingdom. The limited amount of information published by the SFO in the United Kingdom significantly restricts the opportunity for empirical assessment of enforcement outcomes. However, we show that the United Kingdom copies many of the characteristics of the United States enforcement system, including its use of settlements in corporate bribery cases. We explain why the difference between the expected sanction in court and the sanction proposed in a settlement offer will influence the number of concluded settlements in the United States and the United Kingdom. When the sanction gap is small, the defendant has a realistic opportunity to decline an offered settlement and have its case tested in court. When the sanction gap is large, the option of declining a settlement can appear as an illusion, and if so, it means that there is no real option of independent third-party review of the case. In the United States, we know from the sentencing guidelines that the sanction gap is large even before court costs and potential collateral claims are considered. When these are added, the sanction gap becomes large enough to dissuade almost any firm from declining a settlement offer. We also show that the increase in the use of settlement might have a self-increasing effects, as the reduction in publicly available information increase the uncertainty regarding the practice of the law, which makes the defendant more inclined to accept a settlement offer.

Our study underscores the still existing challenges attached to the balance between efficient enforcement and fair outcomes, while investigating attributes of settlements that can help overcome some of the side-effects. Considerate use of settlements has the potential of improving the efficiency of law enforcement in corporate liability cases. This is highly needed in an ever more complex global economy, where new trends in economic crime requires a speedy development in law enforcement. As governments around the globe develop guidelines for the use of settlement in corporate bribery cases (OECD 2019), our results remind them of the importance of judicial oversight, access to case information for the public, and limits to the size of the expected sanction gap, so that corporations have a real option of having their case tried in court.

Notes

US Department of Justice, “Herbalife Nutrition Ltd. Agrees to Pay Over $122 Million to Resolve FCPA Case” news release, August 28, 2020.

UK Serious Fraud Office, “SFO enters into €991m Deferred Prosecution Agreement with Airbus as part of a €3.6bn global resolution” press release, January 31, 2020.

Makinwa and Søreide (2018) provide survey results on how firms are held accountable around the world, including in most countries in Europe. The data were collected with the help of the Structured Criminal Settlements Subcommittee of the International Bar Association (IBA), based on a survey of its members conducted in 2017. The survey is part of the project Towards Global Standards in Structured Criminal Settlements for Corruption Offences. Lawyers from 66 countries reported on how negotiated settlements are regulated around the world.

See: Recommendation of the Council for Further Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions (OECD/LEGAL/0378).

For further investigation on the deterrent effect of corporate self-reporting and self-policing, see Iwasaki (2020).

For simplicity we consider x to be a fine, representing the monetary value of the sum of sanctions imposed by the court like a fine, jail for individuals in the firm, debarment etc.

A settlement also imposes a cost on the defendant beyond that of the sanction, like expenses to lawyers, reputational cost, etc. we consider this cost to be part of the sanction a.

The size of k will depend on several factors like the size of the case, the firm’s ability to hire many and expensive lawyers, and whether or not the defendant is found guilty.

The social cost of trial, C, may include a concern for the accused, in addition to society’s expenses, yet the cost of trial from the perspective of the accused, k is a different variable, and therefore, k and C are presented separately.

This is a simplification. In reality, the prosecutor’s disutility of sentencing an innocent (versus not sanctioning a guilty) defendant may be influenced by motifs that diverge from that of society, such as personal career development or corruption. Such aspects, however, are not the focus of our analysis.

With a pooling offer, the two types of defendants choose the same strategy. With a separating offer, the two types of defendants choose different strategies.

See Reinganum (1988) first proposition of a sequential equilibrium.

Formally, it would be correct to refer to E(x) because x is an expected variable. We simplify the expression because the difference between the expectation and and the actual sanction has no role in our model. For example, we do not consider attitudes towards risk. See Søreide (2009) for a discussion of corruption and attitudes towards risk.

Collateral damages include consequences that may arise after the firm is convicted of a crime, for example debarment from public procurement, civil law suits from previous business partners, class actions or law suits from clients. Collateral damages can also be a concern when the defendant is an individual, and aspects of our extension of the model can apply to individuals, while this is not included in Reinganum’s model.

While the risk of collateral damages matter for corporate defendants’ decision, see Williams-Elegbe (2020), the probability of such costs is not necessarily related to any of the aspects addressed this far, and is therefore treated as an exogenous variable.

While this implies an over-simplification of the corporate governance situation and possible contention within a firm, it allows us to keep focus on the prosecutor and the firm as the two parties negotiating the settlement.

See Easterbrook (1992) for a discussion on the ethical aspects of allowing a defendant to negotiate a sanction when the pool of defendants can contain innocent actors.

In the plea bargain literature this is already a much addressed concern, see for example Grossman and Katz (1983), and here we explain why the problem is not any smaller for corporate offenders, even if these are assumed to engage clever lawyers for such circumstances.

See Mungan (2019) for a comparison of N/DPAs and convictions, and the different effect these law enforcement tools have on public information on deterrence.

Both the United States and the United Kingdom publish summaries of concluded settlements. Across other jurisdictions, this varies greatly, from full transparency to no transparency (Makinwa and Søreide 2018).

An example of this is the SNC Lavalin case where the Canadian Prime Minister Trudeau, who sided with the firm, stated that “[...] a criminal conviction would imperil jobs in Quebec because it would have barred the company from bidding on government contracts.” Eventually the firm was not debarred because a subsidiary of the firm accepted a settlement which did not include the parent company. See: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/18/world/canada/snc-lavalin-guilty-trudeau.html.

The argument of avoiding debarment was important in the DPA between SFO and Rolls Royce, as “A DPA is a statutory means by which a company can account to a court for conduct without suffering the full consequences of a criminal conviction, which might include international disbarment from competition for public contracts.” See: https://www.sfo.gov.uk/2017/01/17/sfo-completes-497-25m-deferred-prosecution-agreement-rolls-royce-plc/ However, in most countries firms are seldom debarred, despite procurement regulations that call for mandatory debarment following a guilty plea or verdict (Auriol and Søreide 2017).

In this context we consider rule of law to “require [...] that limitations on the legal rights of individuals must be determined by laws, rather than by potentially arbitrary and unconstrained decisions of individual government actors” (Arlen 2016). For an extended analysis of the rule of law see Fallon (1997).

This type of liability is known as respondeat superior, meaning that the principal can be held liable for crimes committed by their agent if the principal gains, or was intended to gain, from the crime committed. When the principal is a corporation the agent can be any employee of the firm, even a low-level employee.

Officially, the OECD Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions.

An NPA or DPA is considered a settlement without conviction if the terms of the agreement are fulfilled. An NPA is not filed in court, and if the defendant fulfils the terms of the agreement with the prosecutor, the case is then closed. A DPA is filed with the court but put on hold, and it can be withdrawn if the defendant fulfils the terms of the agreement. From here on, we will refer to them jointly as N/DPAs.

For a better understanding of the corporation’s role in international bribery cases, and insights into enforcement cases brought by the DOJ see (Chan et al. 2021).

This figure comprises all known settlements in the given period, resolved though a plea bargain, NPA or DPA. The settlements do not only deal with corporate bribery, but also antitrust, fraud, tax evasion, and environmental violations.

See, for example, Gibson (2018).

United States v. Panasonic Avionics Corporation (D.C.Cir. 2018).

Based upon USSG § 8C2.4(a)(2), and because the pecuniary gain exceeds the fine in the Offense Level Fine Table from the 2014 USSG, pursuant to § 8C2.4(e)(1).

US Department of Justice, “Panasonic Avionics Corporation Agrees to Pay $137 Million to Resolve Foreign Corrupt Practices Act Charges,” news release, April 30, 2018.

SEC administrative proceeding no. 3-18459 against Panasonic Corporation, https://www.sec.gov/litigation/admin/2018/34-83128.pdf.

United States Justice Manual 9-27.600-650.

Ibid. 9-27.600.

Søreide and Vagle (2020) present a measure of prosecutorial discretion that allows for cross-country comparison. They use this measure to study relationships between the freedoms granted to the prosecutor and countries’ notions of criminal law efficiency, as well as their political and economic context.

We do not address the fact that some judges are elected in the United States. As we study corporate bribery cases, which are usually brought in federal court, where the judges are appointed, the election of judges is not relevant for our study.

The Bribery Act 2010 is the United Kingdom’s criminal law relating to bribery. See Arlen (2020) for an assessment of the narrow scope of corporate criminal liability in the United Kingdom.

United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) and OECD Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions.

See (Lord 2013) for an analysis on the development of formal and informal systems of law enforcement in the United Kingdom to combat international corporate bribery.

See the page on Deferred Prosecution Agreements on the SFO website, https://www.sfo.gov.uk/publications/guidance-policy-and-protocols/deferred-prosecution-agreements/.

DPA Code, sections 2.8.1.i-iii.

For more information on the cases, see the Deferred Prosecution Agreements page on the SFO website (see supra note 24).

DPA Code.

Ibid.

DPA Code.

Sentencing Council, “Corporate Offenders: Fraud, Bribery and Money Laundering” (hereafter referred to as the UK sentencing guidelines), https://www.sentencingcouncil.org.uk/offences/crown-court/item/corporate-offenders-fraud-bribery-and-money-laundering/.

Information on the LIBOR case is available on the SFO website, https://www.sfo.gov.uk/cases/libor-landing/. The case involved alleged fraud in connection with the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR).

For the complete United Kingdom sentencing guidelines see: https://www.sentencingcouncil.org.uk/offences/crown-court/item/corporate-offenders-fraud-bribery-and-money-laundering/.

DPA Code, section 2.8.2.vi.

Oded (2020) evaluates effort by the US DOJ to reduce the unpredictability defendants face when they risk multiple piled-on prosecutions.

DPA Code, section 2.8.2.vii.

UK sentencing guidelines, Step 5, Adjustment of Fine.

Bribery Act 2010, chapter 23, sections 11(2) and 11(3).

UK sentencing guidelines, section 8.4.

See the U.S. Sentencing Commission 2018 Guidelines Manual and the U.K. Sentencing Council Sentencing Guidelines.

See the page on Sarclad Ltd. on the SFO website, https://www.sfo.gov.uk/cases/sarclad-ltd/.

Statement from the DOJ press release:“[...] Rolls-Royce did not disclose the criminal conduct to the department until after the media began reporting allegations of corruption and after the SFO had initiated an inquiry into the allegations [...]” See: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/rolls-royce-plc-agrees-pay-170-million-criminal-penalty-resolve-foreign-corrupt-practices-act.

See Søreide and Vagle (2020) for a debate on efficiency in law enforcement.

References

Alexander, C. R., & Cohen, M. A. (2015). The evolution of corporate criminal settlements: An empirical perspective on non-prosection, deferred prosecution, and plea agreements. American Criminal Law Review, 52, 537–593.

Arlen, J. (2016). Prosecuting beyond the rule of law: Corporate mandates imposed through deferred prosecution agreements. Journal of Legal Analysis, 8(1), 191–234.

Arlen, J. (2020). The potential promise and perils of introducing deferred prosecution agreements outside the U.S. In: Søreide, Tina, & Makinwa, Abiola (eds), Negotiated Settlements in Bribery Cases: A Principled Approach. Edward Elgar Publishing.