Abstract

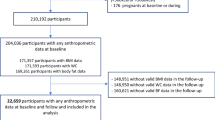

Women who drink light-to-moderately during pregnancy have been observed to have lower risk of unfavourable pregnancy outcomes than abstainers. This has been suggested to be a result of bias. In a pooled sample, including 193 747 live-born singletons from nine European cohorts, we examined the associations between light-to-moderate drinking and preterm birth, birth weight, and small-for-gestational age in term born children (term SGA). To address potential sources of bias, we compared the associations from the total sample with a sub-sample restricted to first-time pregnant women who conceived within six months of trying, and examined whether the associations varied across calendar time. In the total sample, drinking up to around six drinks per week as compared to abstaining was associated with lower risk of preterm birth, whereas no significant associations were found for birth weight or term SGA. Drinking six or more drinks per week was associated with lower birth weight and higher risk of term SGA, but no increased risk of preterm birth. The analyses restricted to women without reproductive experience revealed similar results. Before 2000 approximately half of pregnant women drank alcohol. This decreased to 39% in 2000–2004, and 14% in 2005–2011. Before 2000, every additional drink was associated with reduced mean birth weight, whereas in 2005–2011, the mean birth weight increased with increasing intake. The period-specific associations between low-to-moderate drinking and birth weight, which also were observed for term SGA, are indicative of bias. It is impossible to distinguish if the bias is attributable to unmeasured confounding, which change over time or cohort heterogeneity.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

O’Leary CM, Bower C. Guidelines for pregnancy: what’s an acceptable risk, and how is the evidence (finally) shaping up? Drug Alcohol Rev. 2012;31(2):170–83.

Patra J, Bakker R, Irving H, Jaddoe VW, Malini S, Rehm J. Dose-response relationship between alcohol consumption before and during pregnancy and the risks of low birthweight, preterm birth and small for gestational age (SGA)-a systematic review and meta-analyses. BJOG. 2011;118(12):1411–21.

Henderson J, Gray R, Brocklehurst P. Systematic review of effects of low-moderate prenatal alcohol exposure on pregnancy outcome. BJOG. 2007;114(3):243–52.

Strandberg-Larsen K, Andersen AM. Alcohol and fetal risk: a property of the drink or the drinker? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90(3):207–9.

Niclasen J. Drinking or not drinking in pregnancy: the multiplicity of confounding influences. Alcohol Alcohol. 2014;49(3):349–55.

Kesmodel U, Kesmodel PS, Larsen A, Secher NJ. Use of alcohol and illicit drugs among pregnant Danish women, 1998. Scand J Public. Health. 2003;31(1):5–11.

Lange S, Quere M, Shield K, Rehm J, Popova S. Alcohol use and self-perceived mental health status among pregnant and breastfeeding women in Canada: a secondary data analysis. BJOG. 2015;123(6):900–9.

Abel EL. Maternal alcohol consumption and spontaneous abortion. Alcohol Alcohol. 1997;32(3):211–9.

Olsen J. Options in making use of pregnancy history in planning and analysing studies of reproductive failure. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1994;48(2):171–4.

McManemy J, Cooke E, Amon E, Leet T. Recurrence risk for preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(6):576.e1-6.

Voskamp BJ, Kazemier BM, Ravelli AC, Schaaf J, Mol BW, Pajkrt E. Recurrence of small-for-gestational-age pregnancy: analysis of first and subsequent singleton pregnancies in The Netherlands. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208(5):374–6.

Albertsen K, Andersen AM, Olsen J, Gronbaek M. Alcohol consumption during pregnancy and the risk of preterm delivery. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(2):155–61.

Strandberg-Larsen K, Jensen MS, Ramlau-Hansen CH, Gronbaek M, Olsen J. Alcohol binge drinking during pregnancy and cryptorchidism. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(12):3211–9.

Hedegaard M, Henriksen TB, Sabroe S, Secher NJ. Psychological distress in pregnancy and preterm delivery. BMJ. 1993;307(6898):234–9.

Olsen J, Melbye M, Olsen SF, et al. The Danish National Birth Cohort–its background, structure and aim. Scand J Public Health. 2001;29(4):300–7.

Jaddoe VW, van Duijn CM, van der Heijden AJ, et al. The generation R study: design and cohort update 2010. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(11):823–41.

Olsen J, Frische G, Poulsen AO, Kirchheiner H. Changing smoking, drinking, and eating behaviour among pregnant women in Denmark. Evaluation of a health campaign in a local region. Scand J Soc Med. 1989;17(4):277–80.

Guxens M, Ballester F, Espada M, et al. Cohort profile: the INMA–INfancia y Medio Ambiente–(environment and childhood) project. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(4):930–40.

Magnus P, Birke C, Vejrup K, et al. Cohort profile update: the norwegian mother and child cohort study (MoBa). Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(2):382–8.

Richiardi L, Baussano I, Vizzini L, Douwes J, Pearce N, Merletti F. Feasibility of recruiting a birth cohort through the Internet: the experience of the NINFEA cohort. Eur J Epidemiol. 2007;22(12):831–7.

Guldner L, Monfort C, Rouget F, Garlantezec R, Cordier S. Maternal fish and shellfish intake and pregnancy outcomes: a prospective cohort study in Brittany. France Environ Health. 2007;6:33.

Chatzi L, Plana E, Daraki V, et al. Metabolic syndrome in early pregnancy and risk of preterm birth. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(7):829–36.

Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, Mor J, Kogan M. A United States national reference for fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87(2):163–8.

Organization UNESaC. ISCED (1997) International standard classification of education. 2006. http://www.uis.unesco.org/Library/Documents/isced97-en.pdf.

Bakker R, Pluimgraaff LE, Steegers EA, et al. Associations of light and moderate maternal alcohol consumption with fetal growth characteristics in different periods of pregnancy: the generation R study. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(3):777–89.

Dale MT, Bakketeig LS, Magnus P. Alcohol consumption among first-time mothers and the risk of preterm birth: a cohort study. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26(4):275–82.

Pfinder M, Kunst AE, Feldmann R, van Eijsden M, Vrijkotte TG. Preterm birth and small for gestational age in relation to alcohol consumption during pregnancy: stronger associations among vulnerable women? Results from two large Western-European studies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:49.

Popova S, Lange S, Probst C, Gmel G, Rehm J. Estimation of national, regional, and global prevalence of alcohol use during pregnancy and fetal alcohol syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Global Health. 2017;5(3):e290–9.

Strandberg-Larsen K, Andersen AN, Kesmodel US. Unreliable estimation of prevalence of fetal alcohol syndrome. The Lancet Global Health. 2017;5(6):e573.

Kesmodel US, Petersen GL, Henriksen TB, Strandberg-Larsen K. Time trends in alcohol intake in early pregnancy and official recommendations in Denmark, 1998–2013. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016;95(7):803–10.

EURO-PERISTAT project, with SCPE EUROCAT, EURONEOSTAT (2008) European Perinatal Health Report 2008.

Nohr EA, Frydenberg M, Henriksen TB, Olsen J. Does low participation in cohort studies induce bias? Epidemiology. 2006;17(4):413–8.

Jacobsen TN, Nohr EA, Frydenberg M. Selection by socioeconomic factors into the Danish National Birth Cohort. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(5):349–55.

Nilsen RM, Vollset SE, Gjessing HK, et al. Self-selection and bias in a large prospective pregnancy cohort in Norway. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2009;23(6):597–608.

Pizzi C, De Stavola BL, Pearce N, et al. Selection bias and patterns of confounding in cohort studies: the case of the NINFEA web-based birth cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(11):976–81.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the CHICOS consortium and the study coordination groups, participants and funders of the participating birth cohort studies: the Aarhus Birth Cohort (ABC), the Danish National Birth Cohort (DNBC), the Generation R cohort (GenR), the INMA study, Healthy Habits for two (HHf2), The Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort (MoBa), the Nascita e INFanzia: gli Effetti dell’Ambiente study (NINFEA), the endocrine disruptors: longitudinal study on pathologies of pregnancy, infertility and childhood study (PELAGIE) and Mother Child Cohort in Crete (RHEA). The MoBa data used is from the 6th version.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Commission FP7 Programme [Health –F2-2009-241604], University of Copenhagen, and KSL was funded by the Danish Council for Independent Research I Medical Sciences (grant identifier number: 09-066049).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KSL, GP and AMNA designed the study. GP and KSL analysed data and drafted the paper. All authors contributed to the analysis plan and data interpretation and critically revised the paper. Authors participated in two workshops during spring 2012 at which the analysis plan and data interpretation were discussed.

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Strandberg-Larsen, K., Poulsen, G., Bech, B.H. et al. Association of light-to-moderate alcohol drinking in pregnancy with preterm birth and birth weight: elucidating bias by pooling data from nine European cohorts. Eur J Epidemiol 32, 751–764 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-017-0323-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-017-0323-2