Abstract

Developmental heterogeneity of youth conduct problems has been widely assumed, leading to the identification of distinctive groups at particular risk of more serious problems later in development. The present study intends to expand the main results of a prior study focused on identifying developmental trajectories of conduct problems (Stable-low, Stable-high, and Decreasing), by analyzing their developmental course and related outcomes during middle/late adolescence and early adulthood. Two follow-up studies were conducted 10 and 12 years after the initial study with 115 and 122 youths respectively (mean = 17.29 and 19.18). Overall results underline that the Early-onset persistent group showed the highest risk-profile; the Childhood-limited group revealed a moderate level of later maladjustment; and the Adolescence-onset group, currently identified, showed a significant peak of risk particularly in middle/late adolescence. These findings provide a more comprehensive representation of youth conduct problems, and open new means of discussion in terms of preventive intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heterogeneity in presentation, origins, developmental course, and prospectively related outcomes of child and youth conduct problems has been increasingly recognized, providing a significant challenge for researchers and clinicians in this field [1]. At this regard, beyond assuming conduct problems as a unitary construct, developmental trajectories, with specific characteristics, risks and needs, should be addressed in research, and assumed in clinical contexts. From a developmental psychopathology perspective, there have been many efforts in order to face this challenge through the identification of distinctive groups of problematic youths with different risk profiles and, likely, different etiologies and trajectories [2]. Understanding the distinctive course of developmental trajectories of conduct problems may help in identifying specific groups of problematic youths at increased risk for future behavioral and psychosocial maladjustment [3]. Through this knowledge new theoretical and practical advances could be outlined, shedding new light on diagnostic classification, prevention and intervention.

Most of the studies conducted in this field have identified 3–5 developmental groups, representing distinctive developmental pathways from childhood to adolescence [4]. Most of them typically distinguish an early-onset persistent group, a late-onset or adolescence-limited group, and a non-problematic group [5–7]. These findings would be in line with developmental models of problematic behavior, suggesting a distinction between an early- versus a late-onset of conduct problems [8, 9]. According to these models, the early or childhood-onset group includes children with an early onset of behavioral problems as a consequence of a dysfunctional transactional process, which involves a temperamental vulnerable child (e.g., impulsive) and a poor socialization environment (e.g., coercive parenting). These child-family coercive interactions tend to escalate during the school years, leading to problematic behavior affecting other social functioning areas, and impacting other relevant environments (e.g., school involvement, academic performance, peer interactions) through a kind of snowball effect [10]. This cascade of accumulating risk factors would limit the adequate development of appropriate behaviors. As these models suggest, these children tend to manifest a more serious and persistent pattern of problematic behavior, showing a great deal of continuity through childhood and into adolescence and adulthood [11]. In contrast, the late- or adolescence-onset group exhibits a significant peak of behavioral problems at the onset of adolescence. Developmental models have suggested that those problems may emerge as an exacerbated expression of normative development and adolescent adjustment. According to Moffitt [8, 11], their problematic behavior tends to be linked to some proximal risks (e.g., poor parental monitoring, deviant peer affiliations), as well as to a lack of bonds with prosocial institutions and activities. It has been also postulated that this adolescence-onset group usually shows lower risk of continuity, being more likely to leave their non-normative behaviors as they take on adult prosocial roles, assume more mature decision-making, and spend less time with deviant peers.

Along with these childhood- and adolescence-onset groups, research on developmental trajectories of conduct problems has traditionally identified a decreasing or childhood-limited pattern, including children with early-onset conduct problems that significantly decrease into adolescence [12]. This childhood-limited group was not initially anticipated in developmental models, which largely considered the childhood-onset as a life course persistent pattern [13]. Some hypotheses have been proposed in order to explain the distinctive trajectory of problematic behavior observed in both the early-onset persistent and the childhood-limited groups. One of the most supported was the suggestion of different mechanisms of change (e.g., decreasing in rejection by peers or low family adversity) which would favor the reduction of problematic behavior within the childhood-limited group [14]. However, some authors also noticed that many of the studies conducted so far have failed to demonstrate that the childhood-limited group indeed represents “true recoveries” [5]. As reported by Odgers et al. [15], when later outcomes are analyzed in an extended period, childhood-limited youths seem to experience isolated problems in adulthood (e.g., internalizing disorders, smoking), although they were faring significantly better than their early-onset persistent counterparts.

All the results outlined in prior research have led to reinforce the concept of conduct problems as a dynamic and ongoing process, with multiple factors interacting in complex developmental mechanisms leading to many different outcomes [7]. Bearing this in mind, and considering the need of longitudinal studies on child behavioral development in the Spanish context, a new study has been recently conducted in a sample of Spanish children and adolescents [16]. It was mainly devoted to identifying and examining developmental trajectories of conduct problems measured in three different waves from childhood to early adolescence, spanning a 6-year period. 186 boys (71.5 %) and girls (28.5 %), aged 6–11 at onset, were classified into three main developmental groups through Latent Class Growth Analysis (LCGA): Stable low (n = 117; 60.7 % boys) with children showing low levels of problematic behavior through childhood and into adolescence; Stable high (n = 35; 85.7 % boys), defined as the early-onset persistent profile, with children with high and stable levels of conduct problems; and Decreasing (n = 34; 94.1 % boys), grouping children with early-onset conduct problems that showed a significant decrease over the analyzed period. As can be seen, the adolescence-onset group did not emerge in this study. Although it might be initially surprising, this result should be also expected given the mean age of participants in the last wave of the study (i.e., around 14). Both early precursors and adolescence concurrent outcomes were examined. The Decreasing group seemed to suffer from similar early temperamental impairments to their Stable high counterparts (i.e., high levels of psychopathic traits, impulsivity and low empathy) [15], although the tendencies clearly showed worse levels for the Stable high group [17]. In contrast, and as was expected, different patterns of related outcomes clearly emerged in early adolescence, with the Stable high group showing the highest risk profile characterized by higher levels of psychopathic traits, ADHD symptoms, reactive and proactive aggression, and lower scores in social competence skills. According to prior research, it has been suggested that this Stable high or early-onset persistent group may act as a potential identifier for long-lasting serious behavioral and psychosocial problems [7].

Based on the foregoing, the current study intends to expand the main results obtained so far, and consider some of the limitations observed in the previous study (e.g., the absence of the adolescence-limited group, results just spanning up to early adolescence) [16], as well as the still unresolved needs in this field (e.g., further analysis of the childhood-limited group) [5, 15]. To this end, new follow-up assessments were conducted with the same Spanish sample in middle/late adolescence and early adulthood. It has been developed with the main purpose of further exploring developmental trajectories of conduct problems by specifically examining (1) whether the adolescence-onset group may emerge in these new assessment periods; (2) the later development of youth conduct problems by analyzing behavioral and psychosocial outcomes linked to specific developmental trajectories; and (3) the specific developmental course of the childhood-limited group, trying to delimit whether they indeed represent “true recoveries” later in development.

Method

Participants

Data was gathered from the UDIPRE study, a prospective longitudinal research conducted over a 12 year-period in Galicia (NW Spain). It was overall devoted to evaluating behavioral, emotional, personality, and psychosocial development from childhood to late adolescence/early adulthood through a multi-informant perspective (parent-, teachers-, and self-reports). The study also aims specifically to identify, describe and understand potential early correlates and precursors for later maladjustment. This study started in 2003 (T1) with an initial sample of 192 boys (74.2 %) and girls (27.6 %), aged 6–11 (M = 8.05, SD = 1.49). Participants came from urban and rural areas of Galicia, and they were studying in 34 elementary public schools. The schools were located in predominantly working-class communities, with no diversity in terms of ethnicity, and the academic level of participant’s principal caregiver was overwhelmingly elementary (61.2 %). The family structure was generally composed of a nuclear family (81.15 %), with two children in most cases (60 %). Under Spanish criteria, a large proportion of the sample would fit in lower or lower-middle SES (87.9 %), which is representative of this Spanish region. This sample was followed-up through new four studies conducted 3 (T2), 6 (T3), 10 (T4), and 12 (T5) years after the initial study.

Developmental trajectories of conduct problems were identified using data from T1, T2, and T3, with sample details described in prior research [16]. The later developmental course of these groups, which constitutes the main objective of this study, was analyzed using data from T4 and T5 of UDIPRE study. In T4 data was collected in 115 youths (64.3 % boys), aged 15–20 (M = 17.29; SD = 1.35), with most of them (78.26 %) studying at different levels (Secondary school, Vocational training, University). Information was provided by both parents and youths. In T5 122 youths (66.4 % boys), aged 17–22 (M = 19.18; SD = 1.33), participated in the study. Most of them were still studying (76 %), whereas 10.8 % were working, 2.5 % were studying and working, and the remaining 10.7 % were neither studying nor working. In this last follow-up study information was provided just by youths through self-reports. The level of attrition among T1–T4 and T1–T5 was 40 and 36.5 % respectively. Overall, no relevant differences were observed in terms of age, parents’ academic level, SES, and initial levels of conduct problems between youths participating in all the assessments, and those missing some of them. The only exception was observed for participants missing the last follow-up (T5), who showed significantly higher levels of initial conduct problems than participants in T5, t (170) = 3.78, p < .001.

Variables and Measures

In order to check whether the adolescence-onset group indeed emerged, as well as to test developmental outcomes linked to specific developmental trajectories of problematic behavior, a set of personality (e.g., impulsivity, sensation seeking, psychopathic traits), behavioral (e.g., disruptive and antisocial behavior, aggression, alcohol and drug involvement), and psychosocial (e.g., social competence, school adjustment) measures was assessed in two different time periods: Middle/late adolescence (T4), being reported by both parents and youths, and early adulthood (T5), only through self-reports. The main intention was to provide a general overview about youths’ later maladjustment in different domains. Next all measures, with their corresponding instruments, and the Cronbach’s alpha (α) values obtained for this study, are classified and further described by period (T4 and T5) and informant (parents, youths).

T4 Parent’s Reported Measures

Social Competence

Social competence skills were assessed using the Fast Track Social Competence Scale-Parent Version [18]. This scale comprises 12 items, including six items measuring Emotional Regulation Skills (α = 0.84; e.g., “Copes well with failure”), and the other six measuring Prosocial/Communication Skills (α = 0.87; e.g., “Listens to others point of view”). Parents were asked to score to what extent each statement was true on a scale from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Very well).

Disruptive Behavior

Attention problems, hyperactivity and conduct disorder were assessed through the belonging subscales from the Disruptive Behavior Rating Scale-Parent version (DBRS-PV) [19]. The DBSR-PV is a 45-question screening measure that allows for dimensional scores of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant behavior and conduct disorder, based on DMS-IV symptoms. For each question, parents were asked to indicate the degree to which a statement describes child’s behavior. Attention problems and Hyperactivity, with nine items both of them (α = 0.94 and 0.88, respectively; e.g., “He/she does not pay attention to details”, “He/she is always moving”), were rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 0 (Never) to 3 (Almost always). Conduct disorder, assessed through 15 items (α = 0.77; e.g., “He/she has provoked fires”), was measured in a dichotomous response format of Yes (1) and No (0).

Psychopathic Traits

The parent version of the modified Child Psychopathy Scale (mCPS) [20], consisting of 55 questions in the form of Yes (1)–No (0), was used. The items were classified into 14 dimensions that in turn were grouped into two global factors similar to those used in adult psychopathy studies [21]: Factor 1 (F1; α = 0.80) encompassing the affective and interpersonal traits (e.g., “Is he able to see how other people see?”), and Factor 2 (F2; α = 0.85) including traits from the behavioral dimensions (e.g., “Does he take a lot and not give much in return?”).

T4 Self-Reported Measures

Impulsivity

A reduced version of the Impulsivity sub-scale from the I6 [22], consisting of 12 items, was used. The items were formulated as self-reported questions (e.g., “Do you say and do things without thinking”), and scored with 0 (No or False) or 1 (Yes or True). The total score was used as a global measure of Impulsivity (α = 0.77).

Sensation Seeking

It was assessed using the Emotion and Adventure Seeking subscale from the Sensation Seeking Scale for Children [23]. This scale is composed by 26 items with a forced-choice format (e.g., “I would like to climb a mountain/I think that people who do dangerous things like climb a mountain is crazy”). As a result, a global score of Sensation seeking was created (α = 0.87).

School Adjustment

First, School involvement (α = 0.77) was assessed through six items (e.g., “In the morning I dislike having to go to the school”) rated in a four-point scale from 0 (Completely disagree) to 4 (Completely agree). Second, the level of school Absenteeism was assessed with the question “Did you miss some classes without justified reason last month?” answered on a five-point scale from 0 (No, never) to 4 (Yes, 5 or more times). All the items were adapted from Berry, Phinney, Sam and Vedder [24].

Antisocial Behavior

The short version of the Antisocial Behavior Questionnaire (ABQ) [25] was used to assess the frequency of adolescents’ antisocial behavior in the last 12 months. It is composed of 30 items measuring aggression, vandalism, rule-breaking, thefts and illicit substance abuse, which were answered in a four-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 0 (Never) to 3 (Very often: 10 times or more). The total score of the questionnaire was used as a global measure of Antisocial behavior (α = 0.89; e.g., “Beat someone up in a fight”). In addition, involvement with antisocial peers was assessed through five items, previously used in the UDIPRE study [26]. Each item, scored on a scale from 0 (Never) to 3 (Very often), measures the frequency of peers’ involvement in aggression, vandalism, rule-breaking, thefts and substance abuse (e.g., “Damages or destroys things in public or private places”). A composite score (Peers antisocial behavior; α = 0.78) was created in order to examine the global level of antisocial behavior in peers group.

Aggressive Behavior

The self-report of Reactive and Proactive Behaviors [27] was completed. The scale is composed by six items, with three items assessing Reactive aggression (α = 0.72; e.g., “Yells at others when they have annoyed him/her”), and three measuring Proactive aggression (α = 0.89; e.g., “Threatens and bullies someone”). Participants were asked to report their frequency on a scale from 1 (Never true) to 5 (Almost always true).

Alcohol/Drug Involvement

Different measures of alcohol and drug use/misuse have been included. First, Alcohol misuse was measured through the AUDIT-C, a modified version of the 10-question AUDIT instrument. The AUDIT-C is a 3-item alcohol screen tool that can help identify persons who are hazardous drinkers or have active alcohol use disorders. The three items (α = 0.76) were rated on a 5-point scale (0–4), with a different response set for each one: Item 1 (“How often do you have a drink containing alcohol?”) was rated from Never to 4 or more times a week; Item 2 (“How many standard drinks containing alcohol do you have on a typical day?”) ranged from 1 or 2 to 10 or more; and Item 3 (“How often do you have six or more drinks in one occasion?”) was rated from Never to Daily or almost daily. Secondly, as a proximal measure of drug consumption, the frequency of Cannabis use was assessed with the question “How many days have you consumed cannabis in the last month”, extracted from the Drug Consumption Questionnaire [28], an instrument intended to assess different indicators of drug consumption in youths. This question was rated in a 6-point scale ranging from 0 (Never) to 5 (More than 20). Finally, Positive attitudes towards drugs (α = 0.66) were assessed through a 13-item subscale also from the Drug Consumption Questionnaire [28], (e.g., “Consuming drugs would make me happier”). Participants informed about their agreement with items reflecting different attitudes towards drug consumption, including alcohol, tobacco or cannabis in a three-point response set of 0 (Disagreement), 1 (Agreement), and 2 (Indifference).

T5 Self-Reported Measures

Psychopathic Traits

The Youth Psychopathic traits Inventory-Short Form (YPI-S) [29] was used to measure psychopathic traits. It includes 18 items from the original 50 item YPI [30]. The YPI-S has a three-factor structure: The Grandiose-Manipulative or Interpersonal dimension (GD; α = 0.83; e.g., “When I need to, I use my smile and my charm to use others”); the Callous-Unemotional or Affective dimension (CU; α = 0.70; e.g., “To feel guilty and remorseful about things you have done that have hurt other people is a sign of weakness”), and the Impulsive-Irresponsible or Behavioral dimension (II; α = 0.74; e.g., “It often happens that I talk first and think later”). Each factor/dimension contains six items which are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (Does not apply at all) to 4 (Applies very well).

Aggressive Behavior

Reactive and proactive aggression was evaluated through The Reactive-Proactive Aggression Questionnaire [31]. It consists of 23 items, 12 assessing Proactive aggression (α = 0.85; “How often have you vandalized something for fun”), and 11 evaluating Reactive aggression (α = 0.82; “How often have you yelled at others when they have annoyed you”). Participants reported the frequency of each question in a three-point response scale ranging from 0 (Never) to 2 (Frequently).

Alcohol/Drug Involvement

As in T4, Alcohol misuse was assessed through the AUDIT-C 3-item screen (α = 0.83). In addition, participants were asked again for how many days they have smoked cannabis in the last month (Drug Consumption Questionnaire) [28].

All these measures have been previously used in different studies conducted in the Spanish context, showing evidence of internal consistency and construct validity when assessing the intended constructs [16, 26, 32, 33].

Procedure

The UDIPRE study, with all its phases, was approved by the Bioethics Committee at the University of Santiago de Compostela, the Regional Government (Xunta de Galicia), and both the Ministry of Science and Technology, and the Ministry of Education of the Spanish Government.

Procedures for the first three waves of the study have been detailed in prior studies [16, 26]. The fourth wave (T4) started by telephone contact with the families participating in the study to inform them about the specific objectives of this new assessment process, and to request once again their participation. Once agreement was obtained from both parents and youths, a schedule of assessment meetings was organized. The questionnaires were administered by qualified psychologists who were always present in order to solve any question or doubt regarding the questionnaire. Both parents and youths completed the questionnaire individually, with confidentiality completely guaranteed. As regards parents’ reports, questionnaires were completed by the person who attended the assessment meeting (usually youths’ mothers). When both parents were present, they completed one questionnaire together answering each item by mutual agreement.

For the latest wave (T5), only youths were contacted by telephone, and invited to participate in this new assessment. After obtaining their agreement for participating, the procedure was similar to prior follow-ups, with an organized schedule for assessment meetings with qualified staff, and with participants completing the questionnaire individually under conditions of confidentiality.

Statistical Analyses

Firstly, in order to identify the adolescence-onset group, Hierarchical Cluster Analysis was conducted with youths within the non-problematic group. Sensation seeking, impulsivity, school adjustment, antisocial behavior, positive attitudes towards drugs, drug consumption and peers’ antisocial behavior were included as clustering variables. The Ward method was used for clustering, and Squared Euclidean Distance was selected as the measure to define distance between clusters. Secondly, differences across developmental groups in a set of behavioral and psychosocial variables were measured in T4 and T5 with Multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA), with age and gender as covariates and using the Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons. The strength of differences was assessed through the partial effect size statistic (ŋ²), and interpreted according to Cohen’s guidelines [34] as small (>0.05), medium (0.06 to 0.14), and large (<0.14). Variables used in the analyses were grouped by both informant (i.e., parents- and self-reports) and content (i.e., psychopathic traits, aggressive behavior, social competence; alcohol/drug involvement). Finally, Levene’s test was used for testing homoscedasticity between groups in all the analyzed variables, and Welch F-test correction with Games-Howell post hoc test for examining differences between groups in those variables that did not show equal variances according to Levene’s. All the analyses were conducted on IBM SPSS Statistics 20.

Results

Developmental Trajectories of Conduct Problems: Identifying the Adolescence-Onset Group

Stable low, Stable high, and Decreasing groups identified in a prior study [16], were compared in the large set of behavioral and psychosocial variables measured in both middle/late adolescence (T4), and early adulthood (T5). Overall, these comparisons revealed that the Stable high group showed the worst pattern of results with the highest levels of adolescent maladjustment, behavioral problems and psychopathic traits, and the lowest of social competence.Footnote 1

Surprisingly, these results also showed that neither in T4 nor in T5 there were differences in alcohol and drug misuse between the analyzed groups. Even more relevant was the fact that the values observed for each group, including the Stable low, were sometimes very similar (e.g., cannabis use, positive attitudes towards drugs). Considering the high prevalence of alcohol and drug consumption among adolescents, it could be hypothesized that most participants in the study have a similar pattern of consumption in middle/late adolescence and early adulthood, including those considered as non-problematic. However, it is also true that differences between individuals may exist and, thus, more problematic levels of consumption should be expected for certain groups. These results led us to consider the possibility that the Stable low group may mask a group of individuals showing some kind of adolescent maladjustment that has not emerged before (i.e., the adolescent-onset group).

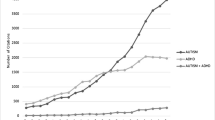

In order to test this hypothesis, a hierarchical cluster analysis was conducted within the Stable low or non-problematic group in T4 (i.e., middle/late adolescence). Self-reported measures traditionally relevant in defining the adolescence-onset profile were included as clustering variables [8]: Sensation seeking, impulsivity, school implication, antisocial behavior, drug consumption, positive attitudes towards drugs, and peers’ antisocial behavior. Two to three solutions were explored, with the theoretically expected two factor solution emerging as the most interpretable. As displayed in Fig. 1, the first cluster, named “Non-problematic”, grouped 57 boys (47.37 %) and girls (52.63 %) with low levels in all the clustering variables, except school involvement, which showed a positive Z-score. The second cluster, named “Adolescence-onset”, grouped 20 boys (65 %) and girls (35 %) who showed the inverse pattern in clustering variables than the observed for the Non-problematic group, with higher levels (i.e., values above the mean) of sensation seeking, impulsivity, antisocial behavior, positive attitudes towards drugs and peers’ antisocial behavior, and lower of school involvement. Clusters were compared on clustering variables through a Student’s t test, showing significant differences in all of them (p < .001, “see footnote 1”). In addition, clusters showed differences for age (mean age of 17.11 and 17.90 for the Non-problematic and the Adolescence-onset respectively), t = −2.41(75), p < .05, but not in terms of gender, χ² = 1.84(1), p > .05.

New Developmental Groups: Testing Differences in T4 and T5 Outcomes

After identifying the adolescence-onset group, and with the aim of providing a clearer representation of developmental trajectories of youth conduct problems, new developmental groups were formulated. By combining developmental trajectories initially identified (i.e., Stable low, Stable high, and Decreasing) [16], and the clusters previously described, new groups more representative of participants’ developmental trajectories in T4 were established: The Non-problematic (n = 57), previously identified as the Stable low, with youths showing low levels of behavioral and psychosocial problems from childhood to adolescence; the Adolescence-onset (n = 20), including youths who showed normative development across childhood but with a peak in problematic behavior during adolescence; the Early-onset persistent (n = 35), formerly the Stable high, which grouped participants with an early onset of problematic behavior that persists and affects other functioning areas across childhood and adolescence; and the Childhood-limited (n = 34), formerly the Decreasing group, with children showing early-onset conduct problems that significantly decrease up to adolescence. Differences between groups have been observed in terms of age, F = 3.98 (3, 142), p < .001, and gender, χ² = 27.60 (3), p < .05, but not as regards SES, F = 2.07 (2, 120) p > .05. Therefore, both age and gender were included as covariates in subsequent analyses, which compare these groups on main behavioral and psychosocial study variables in both T4 and T5.

T4 Comparisons: Middle/Late Adolescence Outcomes

Comparisons on T4 parents’ reports (see Table 1) showed significant differences in all the combined variables, as well as in all the specific dependent variables. The exception was for conduct disorder, which lost its significance after applying Bonferroni’s correction (p < .017). The Early-onset persistent group showed the highest scores in most analyzed variables, and the lowest in social competence skills. Overall, post hoc comparisons did not reveal substantial differences between groups, particularly between the Adolescence-onset, the Early-onset persistent, and the Childhood-limited. Differences that reached statistical significance showed that the Early-onset persistent performance worse than the Adolescence-onset in terms of emotional regulation, attention problems, hyperactivity, and behavioral psychopathic traits (F2), whereas the differences were significant with the Childhood-limited in terms of conduct disorder and affective psychopathic traits.

With respect to self-reported measures in T4, differences were significant for all the combined variables, as well as for the specific dependent variables when analyzed separately. In contrast with what has been previously observed, the Adolescent-onset group showed the worst adjustment in T4 according to self-reports, with the highest scores in school absenteeism, self and peers’ antisocial behavior, and alcohol/drug involvement (except cannabis use), and the lower in school adjustment. Most of these values were significantly different than the observed for the other groups. The Adolescence-onset group scored equally with the Early-onset persistent group in proactive aggression and alcohol misuse, and with the Childhood-limited as regards alcohol misuse, and positive attitudes towards drugs. The Early-onset persistent group scored higher than the others in reactive aggression, whereas the Childhood-limited group showed the highest levels of cannabis use.

Based on the partial effect size statistic (ŋ²), all significant differences between groups had a medium to large effect size.

T5 Comparisons: Early Adulthood Outcomes

Finally, new developmental groups were compared in variables measured in T5 in order to check for distinctive developmental outcomes in early adulthood (see Table 2). Differences were significantly different for all the combined variables. When independent variables were examined separately, comparisons showed that differences in reactive aggression lost their significance with the Bonferroni’s adjustment (p < .025). As Table 2 displays, youths within the Early-onset persistent group showed the highest scores in psychopathic traits variables, being significantly different than the Adolescence-onset in impulsive/irresponsible, and for aggressive behavior. In contrast, the Adolescence-onset group showed the highest scores in alcohol misuse, with no differences with respect the Early-onset persistent group, and in cannabis use with no relevant differences as regards the Childhood-limited one.

As was observed in prior comparisons, the effect size for statistical significant differences (ŋ²) in comparisons between developmental groups ranged from medium to large.

Replication Analyses: Testing for Homoscedasticity

As can be observed in both Tables 1 and 2, there are some relevant differences between groups in standard errors values. In order to test the significance of those differences, the Levene’s test was used as a measure of homoscedasticity in comparisons. These results revealed significant differences (p < .05) between groups for T4 hyperactivity, conduct disorder, school absenteeism, antisocial behavior, peers’ antisocial behavior, proactive aggression and positive attitudes towards drugs, as well as for T5 YPI-CU, reactive and proactive aggression, alcohol misuse, and cannabis use. Since not MANOVA neither ANOVA account for differences in standard deviation, the Welch’s F-test correction was used on comparisons with the aforementioned variables. Results of Welch’s test did not differ from results of MANCOVA F-tests. Thus, statistically significant differences between groups were observed for all the analyzed variables with the exception of T4 conduct disorder (Welch = 1.19, p = .328), and T5 reactive aggression (Welch = 2.14, p = .114). These two variables did not either show significant differences in MANCOVA F-tests when applying the Bonferroni’s correction. Post-hoc Games-Howell test revealed some marginal differences in comparisons between groups with respect those observed with Tukey’s post hoc test. These differences might be partially due to the effect of age and gender, which cannot be controlled for when using the Welch’s F-test correction (further details of these analyses are available upon request).

Discussion

Child and youth conduct problems constitute a major phenomenon nowadays, with implications at different levels (e.g., individual, family, academic, social) that raise important social concerns [35]. It is widely assumed that conduct problems represent a heterogeneous construct, with different developmental trajectories being easily identifiable, leading to distinguish distinctive groups of children at particular risk for later behavioral and psychosocial maladjustment [2, 3]. With the intention of advancing in this knowledge, the present study was designed for examining, across middle/late adolescence and early adulthood, the developmental course and related outcomes of specific developmental trajectories of conduct problems, identified in a prior study [16]. Results of both studies have allowed the identification of main developmental trajectories in a novel sample, spanning a 12-year period from childhood to early adulthood. Therefore, the Non-problematic, Adolescence-onset, Early-onset persistent, and Childhood-limited groups, were defined in order to provide a more coherent and representative portrait of problematic behavior profiles in our context.

The Early-Onset Persistent Group as the Highest-Risk Profile

In line with previous research, the Early-onset persistent profile showed the worst pattern of results, being at heightened risk of developing later problems in different domains [5, 15, 16, 36, 37]. It should be noted that in middle/late adolescence (T4), youths in the Adolescence-onset group showed similar—and even higher—frequency and severity than the Early-onset persistent [8, 37]. This tendency seemed to change through early adulthood (T5), with Early-onset persistent revealed again as the highest-risk profile, showing a great deal of continuity in problematic behavior across different developmental stages as developmental models usually predict [11].

It was also observed that children in the Early-onset persistent group showed high levels of psychopathic traits throughout the analyzed period, including childhood and early adolescence [16]. This result is significant since psychopathic traits have been frequently linked to long-standing pathways of problematic behavior [39], showing a similar developmental course to conduct problems [40]. At this regard, different authors have introduced psychopathic traits, and particularly the affective dimension or callous-unemotional (CU) traits, in the study of developmental trajectories of conduct problems in order to disentangle the heterogeneity still observed in the early-onset persistent group [41, 42]. These authors suggested that the presence of these traits may help in identifying a specific subgroup of early-onset problematic youths, showing distinctive correlates, etiological mechanisms, developmental course, and related outcomes [39], and being particularly linked to a more severe and persistent pathway of problematic behavior [41, 43]. Regrettably, given the limitations in sample size, the data presented in this study, although reinforcing the role of psychopathic traits in the development of problematic behavior [16], did not allow identification of this specific developmental pattern within the Early-onset persistent group. Considering that only a small percentage of youths with conduct problems would also show high levels of psychopathic and CU traits [39, 44], large data sets are required in order to identifying new developmental groups based on the presence of psychopathic traits. This issue has been highlighted from a developmental perspective as an important milestone for future research [42].

The Identification of the Adolescence-Onset Group

Results of cluster analysis clearly showed that there was a group of youths relatively free of risk in childhood, but who engaged in a pattern of problematic and antisocial behavior during adolescence [11]. As could be expected, this group showed a significant peak in problematic behavior in middle/late adolescence, being at increased risk for a large set of behavioral and psychosocial problems [15, 36, 37]. As was previously outlined, these problems tended to show even higher levels than those observed for Early-onset persistent group. This reinforces the high-risk profile of this group across adolescence, and justifies the great amount of research particularly focused on better understanding this specific pathway [11]. It tends to reduce in early adulthood (T5), although with some increased levels in measures such as alcohol problems and cannabis use. This would be in line with the main prediction of traditional developmental models, which suggests that conduct problems that emerge in adolescence usually show a significant reduction later in development, as youths assume adult roles and responsibilities. This has led to this specific pathway becoming known as the “adolescence-limited” one [8]. However, partially in line with current results, different studies have also revealed that not all youths within the adolescence-onset group desist in their problematic behavior during late adolescence and early-adulthood. According to these studies, some adolescence-onset individuals would continue engaging in problematic behavior up through early-adulthood, albeit at a significantly lower level than the Early-onset persistent group [13, 15].

Given the influence of classic developmental models, which basically distinguishes between early-onset and adolescence-onset groups [8], most previous studies in this field have focused on contrasting the adolescence-onset with the early-onset, without the recognition of the childhood-limited group. However, it has been observed that the Childhood-limited and the Adolescence-onset groups did not significantly differ from each other in levels of most the analyzed variables [5], particularly in terms of alcohol and drug involvement. Some studies have even revealed that these two groups may indeed share some patterns of risk in childhood [12, 15], with differences in later developmental trajectories partially due to environmental influences. This hypothesis opens new means of analysis and discussion for future research. It may lead to accounting for the developmental differences between these two groups along with the early-onset persistent one, as well as for providing a new broad context in developmental analyzing child and youth conduct problems.

Developmental Course of the Childhood-Limited Group

Even considering that in the prior study the Childhood-limited group showed the expected decrease in problematic behavior in late childhood [5, 16], it seemed to be somewhat problematic later in development [15], particularly in middle-late adolescence (T4). Although the pattern of results showed the expected tendencies, there were not statistically significant differences between the Early-onset persistent, the Adolescence-onset, and the Childhood-limited groups in most analyzed variables. Whether these non-significant differences indeed reflect a peak of problematic behavior for youths within the Childhood-limited group is a difficult question to solve in this study, since the limited size of the analyzed groups might be restricting the statistical power of the comparisons. However, the presence of significant differences with the Non-problematic group in many different variables, with higher levels for the Childhood-limited group, may support its middle-risk profile.

Given so, it seems that the Childhood-limited group, after a significant decrease in problematic behavior in childhood and early-adolescence, experiences a moderate increase in behavioral maladjustment later in adolescence, particularly restricted to alcohol and drug misuse. As Odgers et al. [15] suggest, instead of representing a complete recovery group, this profile may represent a type of developmental process that shifts from specific externalizing problems (e.g., conduct disorder, antisocial behavior, aggression) into other domains of later maladjustment. Despite the relevance of these results, it is difficult to extract main conclusions from them; although there seems to be a peak of problematic behavior across adolescence it should be questioned whether there is a real and enduring increase in behavioral maladjustment or, alternatively, if this is just particularly linked to the problems that commonly emerge during that period. Which factors and processes are influencing this varying pattern of developmental outcomes is still an unresolved question. Aside from the preliminary hypotheses trying to explain the developmental course of the Childhood-limited group [14], there seems to be some early risks in common with both the Adolescence-onset and the Early-onset persistent groups [5]. The current study was not designed to address the specifics of these findings but subsequent follow-up analysis as well as new long-term longitudinal studies should go further into these questions. Beyond examining early risks and later outcomes specifically linked with each trajectory, future research will be particularly enriched by examining which factors and processes (e.g., environmental risk exposure, genetic vulnerability, or genetic susceptibility to environmental risk) [5, 11] may impact the distinctive developmental course of each distinctive pathway. The Childhood-limited group, barely assessed in previous research but with unquestionable relevance in terms of prevention and intervention [4], should be considered a key group in this ever increasing field.

To our knowledge, this is the longest longitudinal study assessing child and youth behavioral development in our context, providing an important avenue for future research. By expanding the assessment over a 12-year period, we were able to identify the Adolescence-onset group, and build a more complete representation of developmental trajectories of problematic behavior. In addition, it has allowed the specific analysis of the middle-term developmental course of the Childhood-limited group, a need that has been highlighted in previous research [5, 14, 15]. Finally, a wide range of personality, behavioral and psychosocial measures, assessed through parents’ and youth’s reports, were analyzed at two different time points including the so called emerging adulthood, a key transition period in human development since many changes and new responsibilities must be assumed [45]. In sum, these findings provide evidence supporting the need to examine child and youth problematic behavior from a developmental perspective, conferring a comprehensive and integrated view of processes involved in both normative and problematic development over the life span. It is unquestionable that valuable implications for developmental models of conduct problems can be outlined. Different developmental trajectories of problematic behavior have been now identified in a novel sample, even beyond the main predictions of traditional subtyping approaches (i.e., the Childhood-limited group) [11, 15]. Thus, the developmental heterogeneity of the construct has been noted, supporting the idea that early-starting conduct problems are indeed indicative of a high-risk profile but with other middle-risk groups also identified. Developmental models of conduct problems should be then updated and improved by integrating traditional subtyping approaches with results from the study of developmental trajectories, considering the presence of distinctive profiles with specific risks and needs. Clinical and preventive practice in applied domains could be also enriched by these advances. Youths in high-level trajectories are at increased risk of suffering from later problems [4, 15], so they should be the primary focus of attention in intensive intervention settings. However, since high levels of problematic behavior are generally predictive of many different problems regardless of their developmental course, intervention and prevention programs should also focus on individuals that show severe problematic behavior at any point in childhood and adolescence, specifically targeting the main characteristics of youths in each trajectory, and providing response according to their particular needs [46]. In addition, further knowledge of developmental groups such as the Childhood-limited one will also provide new advances in terms of preventive intervention, leading to identify which factors might be involved in the reduction of externalizing behavior, and which one could maintain this reduction over the life-spam.

Notwithstanding these contributions, the main results of current research should be considered as preliminary given the mentioned issues about sample size. Some limitations and tips for considering in future research should be also borne in mind when interpreting these findings. Firstly, current results, mainly based on tendencies rather than in significant differences, should be interpreted with caution, making it difficult to formulate main conclusions as regards developmental course of the identified trajectories. The presence of non-significant differences between groups may reflect that, indeed, they showed similar levels of the analyzed outcomes. However, since most of these comparisons showed the expected tendencies, they may be also masking potential differences between groups, with the observed non-significant differences being partially due to the limited size of the analyzed groups. Similarly, participant’s age range was relatively large, with some overlapping between ages in the analyzed developmental periods. Although mean age was according to the expected period (i.e., late adolescence and early adulthood), and that participants’ age was included as a covariate in the analyses, further analyses across age groups would be preferable. Limitations in sample size would not allow this; therefore, new studies, including larger data sets, are definitely required. Secondly, since the measure used for identifying developmental trajectories in the prior study (i.e., Child Behavioral Checklist) was not available in the follow-ups included the current study, the Adolescence-limited group was identifying using a different analytical procedure than the remaining developmental groups (i.e., cluster analysis versus LCGA). However, given that problematic behavior among adolescence-onset groups is expected to be relatively transient, it is likely that trajectory-based methods, which are ideal for capturing enduring and constant patterns of development, may be less successful in detecting this type of transient behavioral pathway [15]. Linked to this, clearer differences between groups were mainly observed as regards parents’ reports. Given that parents also reported conduct problems assessed in developmental trajectories, these associations could be partially affected by shared method variance. Thirdly, previous studies have shown that different types of problematic behavior (e.g., aggression, opposition, vandalism), although showing similar developmental trajectories [6], are commonly related to different adult outcomes [4]. In order to provide a more comprehensive knowledge about how conduct problems, with all their variants, develop across periods, future research should focus particularly on how those typologies of problematic behavior may be particularly predictive of different outcomes. This challenge will help in designing more personalized preventive intervention programs.

Summary

Given the significance and prevalence of child and youth conduct problems, as well as their association with long-lasting behavioral and psychosocial impairment, there has been a growing interest in better understanding their development across childhood and adolescence. Developmentally, conduct problems have been largely characterized as a heterogeneous construct, assuming individual differences in developmental trajectories that may help in identifying groups of children at particular risk for more serious later maladjustment. Results of this study have allowed advances in this knowledge by providing a more comprehensive representation of the developmental course of child and youth trajectories of problematic behavior. Therefore, beyond the Non problematic, the Early-onset persistent, and the Childhood-limited groups, the Adolescence-onset profile was also identified. As was also observed in prior research, high levels of conduct problems in both childhood and adolescence impact the middle- and long-term outcomes, regardless of the specific developmental course of this problematic behavior. Being more specific, these results revealed that the Early-onset persistent group showed the highest risk profile, with a great deal of continuity between early conduct problems and later behavioral and psychosocial maladjustment. In middle/late adolescence, the Adolescence-onset group showed similar frequency and severity of analyzed measures to the Early-onset persistent one, highlighting their increasing risk to be involved in a wide range of problematic and antisocial behavior. This pattern tends to diminish later in development, but still shows some problematic levels of behavioral maladjustment in early adulthood. Finally, the Childhood-limited group did not seem to show a profile of completely recovery, moving from specific conduct problems in early childhood to somewhat later maladjustment in different domains. Future research should particularly try to go further into the factors and processes that may impact these developmental trajectories across different developmental stages. To this end, it will be challenging try to elucidate the mechanisms that lead youths to engage in high and stable patterns of serious conduct problems, to significantly reduce their problematic behavior over time, or to cause their involvement in serious antisocial behavior in adolescence, even if they have been relatively free of risk in childhood. Through this knowledge, new and promising advances could be made in terms of individualized prevention and intervention programs.

Notes

Results available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Rowe R (2014) Commentary: integrating callous and unemotional traits into the definition of antisocial behavior-a commentary on Frick et al. (2014). J Child Psychol Psychiatr 55:549–552

Hyde LW, Burt SA, Shaw DS, Donellan MB, Forbes EE (2015) Early starting, aggressive, and/or callous-unemotional? Examining the overlap and predictive utility of antisocial behavior subtypes. J Abnorm Psychol 124:329–342

Fanti KA, Henrich CC (2010) Trajectories of pure and co-occurring internalizing and externalizing problems from age 2 to age 12: findings from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care. Dev Psychol 46:1159–1175

Reef J, Diamantopoulou S, van Meurs I, Verhulst FC, van der Ende J (2011) Developmental trajectories of child to adolescent externalizing behavior and adult DSM-IV disorder: results of a 24-year longitudinal study. Soc Psychiatr Psychiatr Epidemiol 46:1233–1241

Barker ED, Oliver BR, Maughan B (2010) Co-occurring problems of early persistent, childhood limited, and adolescence onset conduct problem youth. J Child Psychol Psychiatr 51:1217–1226

Nagin DS, Tremblay R (1999) Trajectories of boys’ physical aggression, opposition, and hyperactivity on the path to physically violent and nonviolent juvenile delinquency. Child Dev 70:1181–1196

Thompson R, Tabone JK, Litrownik AJ, Briggs EC, Hussey JM, English DJ, Dubowitz H (2011) Early adolescent risk behavior outcomes of childhood externalizing behavioral trajectories. J Early Adolesc 31:234–257

Moffitt TE (1993) Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior. A developmental taxonomy. Psychol Rev 100:674–701

Patterson GR (1996) Some characteristics of a developmental theory for early onset delinquency. In: Lenzenweger MF, Haugaard JJ (eds), Frontiers of developmental psychopathology. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 81–124

Romero E (1998) Teorías sobre delincuencia en los 90 [Theories on delinquency in the 90s]. Anu Psicol 32:25–49

Moffitt TE (2006) Life-course persistent versus adolescence-limited antisocial behavior. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ (eds) Developmental psychopathology: risk, disorder, and adaptation, 2nd edn, vol 3. Wiley, New York, pp 570–598

Barker ED, Maughan B (2009) Differentiating early-onset persistent versus childhood-limited conduct problem youth. Am J Psychiat 166:900–908

Burt SA, Donnellan MB, Iacono WG, McGue M (2011) Age-of-onset or behavioral sub-types? A prospective comparison of two approaches to characterizing the heterogeneity within antisocial behavior. J Abnorm Psychol 39:633–644

Veenstra R, Lindenberg S, Verhulst FC, Ormel J (2009) Childhood-limited versus persistent antisocial behavior: why do some recover and others do not? The TRAILS study. J Early Adolesc 29:718–742

Odgers DL, Moffitt TE, Broadbent JM, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, Caspi A (2008) Female and male antisocial trajectories: from childhood origins to adult outcomes. Dev Psychopathol 20:673–761

López-Romero L, Romero E, Andershed H (2015) Conduct problems in childhood and adolescence: developmental trajectories, predictors and outcomes in a 6-year follow-up. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 46, 762–773

Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, Horwood LJ (1996) Factors associated with continuity and changes in disruptive behavior patterns between childhood and adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol 24:533–553

Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group (1995) Social competence scale (parent version). Pennsylvania State University, University Park

Barkley RA (1997) Defiant children: a clinician’s manual for assessment and parent training, 2nd edn. Guilford, New York

Lynam DR (1997) Pursuing the psychopath: capturing the fledging psychopath in a nomological net. J Abnorm Psychol 106:425–438

Verschuere B, Candel I, Van Reenen LV, Korebrits A (2012) Validity of the Modified Child Psychopathy Scale for juvenile justice center residents. J Psychopathol Behav 34:244–252

Silva F, Martorell C, Clemente A (1986) Socialization and personality: study through questionnaires in a preadult Spanish population. Personal Individ Differ 7:355–372

Russo MF, Stokes GS, Lahey BB, Christ MAG, McBurnett K, Loeber R et al (1993) A sensation seeking scale for children: a further refinement and psychometric development. J Psychopathol Behav 15:69–86

Berry JW, Phinney JS, Sam D, Vedder P (eds) (2006) Immigrant youth in cultural transition: acculturation, identity and adaptation across national contexts. Erlbaum, Hillsdale

Luengo A, Otero JM, Romero E, Gómez Fraguela JA, Tavares–Filho ET (1999) Análisis de ítems para la evaluación de la conducta antisocial. Un estudio transcultural. [Item analysis in evaluating antisocial behavior. a transcultural study]. Rev Iberoam Diagn Evol 1:21–36

López-Romero L, Romero E, Gómez-Fraguela JA (2015) Delving into callous-unemotional traits in a Spanish sample of adolescents: concurrent correlates and early parenting precursors. J Child Fam Stud 24:1451–1468

Dodge KA, Coie JD (1987) Social information processing factors in reactive and proactive aggression in children’s peer groups. J Personal Soc Psychol 53:1146–1158

Luengo MA, Romero E, Gómez-Fraguela JA, Garra A Lence M (1999) La Prevención del Consumo de Drogas y la Conducta Antisocial en la Escuela: Análisis y Evaluación de un Programa [The prevention of drug consumption and antisocial behavior at school: analysis and assessment of a program]. Ministerio de Educación y Cultura, Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo y Ministerio del Interior, Madrid

van Baardewijk Y, Andershed H, Stegge H, Nilsson KW, Scholte E, Vermeiren R (2010) Development and tests of short versions of the youth psychopathic traits inventory and the youth psychopathic traits inventory-child version. Eur J Psychol Assess 26:122–128

Andershed H, Kerr M, Stattin H, Levander S (2002) Psychopathic traits in non-referred youths: a new assessment tool. In: Blaauw E, Sheridan L (eds) Psychopaths: current international perspectives. Elsevier, The Hague, pp 131–158

Raine A, Dodge K, Loeber R, Gatzke-Kopp L, Lynam D, Reynolds C, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Liu J (2006) The reactive-proactive aggression questionnaire: differential correlates of reactive and proactive aggression in adolescent boys. Aggress Behav 32:159–171

Luengo MA, Villar P, Sobral J, Romero E, Gómez-Fraguela JA (2009) El consumo de drogas en los adolescentes inmigrantes: implicaciones para la prevención [Drug consumption in immigrant adolescents: implications for prevention]. Rev Esp Drogodepend 34:448–479

Orue I, Andershed H (2015) The youth psychopathic traits inventory-short version in Spanish adolescents: factor structure, reliability, and relation with aggression, bullying, and cyber bullying. J Psychopathol Behav 37:563–575

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Erlbaum, Hillsdale

Baker K (2013) Conduct disorders in children and adolescents. Paediatr Child Health 23:24–29

Bongers IL, Koot HM, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC (2008) Predicting young adult social functioning from developmental trajectories of externalizing behavior. Psychol Med 38:989–999

Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM (2007) Conduct and attentional problems in childhood and adolescence and later substance use, abuse and dependence: results of a 25-year longitudinal study. Drug Alcohol Depend 88(Suppl 1):S14–S26

Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Harrington H, Milne BJ (2002) Males on the life-course persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways: follow-up at age 26 years. Dev Psychopathol 14:179–207

Frick PJ, Ray JV, Thornton LC, Kahn RE (2014) Can callous-unemotional traits enhance the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of serious conduct problems in children and adolescents? A comprehensive review. Psychol Bull 40:1–57

Klingzell I, Fanti KA, Colins OF, Frogner L, Andershed AK, Andershed H (2015) Early childhood trajectories of conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits: the role of fearlessness and psychopathic personality dimensions. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev

Frick PJ (2012) Developmental pathways to conduct disorder: implications for future directions in research, assessment, and treatment. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 41:378–389

Waller R, Hyde LW, Grabell AS, Alves ML, Olson SL (2015) Differential associations of early callous-unemotional, oppositional, and ADHD behaviors: multiple domains within early-starting conduct problems? J Child Psychol Psychiatr 56:657–666

López-Romero L, Romero E, Luengo MA (2012) Disentangling the role of psychopathic traits and externalizing behavior in predicting conduct problems from childhood to adolescence. J Youth Adolesc 41:1397–1408

Herpers PCM, Rommelse NNJ, Bons DMA, Buitelaar JK, Scheepers FE (2012) Callous-unemotional traits as a cross-disorders construct. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 47:2045–2064

Arnett JJ (2000) Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol 55:469–480

Andrews DA, Bonta J, Hoge RD (1990) Classification of effective rehabilitation: rediscovering psyhology. Crim Justice Behav 17:19–52

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

López-Romero, L., Romero, E. & Villar, P. Developmental Trajectories of Youth Conduct Problems: Testing Later Development and Related Outcomes in a 12-Year Period. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 48, 619–631 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-016-0686-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-016-0686-8