Abstract

A natural abundance of the air CO2 in NaOH(aq) at low temperature was investigated in terms of cellulose-CO2 interactions upon cellulose dissolution in this system. An organic superbase, namely 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene, DBU, known for its ability to incorporate CO2 in carbohydrates, was employed in order to shed light on this previously overlooked feature of NaOH(aq) at low temperature. The chemisorption of CO2 onto cellulose was investigated using spectroscopic methods in combination with suitable regeneration procedures. ATR-IR and NMR characterisation of regenerated celluloses showed that chemisorption of CO2 onto cellulose during its dissolution in NaOH(aq) takes place both with and without employment of the CO2-capturing superbase. The chemisorption was also observed to be reversible upon addition of water: CO2 desorbed when water was used as regenerating agent but could be preserved when instead ethanol was used. This finding could be an important parameter to take into consideration when developing processes for dissolution of cellulose based on this system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The production of textile fibres is currently a growing market as the extensive use of textiles continues to increase worldwide. Oil-based fibres represent, at 62.1%, the majority of all the textile fibres produced, whilst cotton-based fibres stand for 25.1% (Lenzing 2015). Only 6.4% of the market share is wood-based cellulose fibres, although this is category predicted to increase substantially due not only to the increasing world population but also to the severe environmental problems associated with the cultivation and processing of cotton, such as the use of vast amounts of water and pesticide (Hämmerle 2011).

The most difficult challenge facing the production of textile fibres from wood is the inability of cellulose to dissolve in common solvents: its unique morphology, with a semi-crystalline supramolecular structure, requires solvents capable of overcoming the complex intramolecular interactions within it. There is a number of currently available solvent systems—both aqueous and non-aqueous (e.g. ionic liquids, amine oxides, combinations of organic solvents with salts, NaOH(aq), etc.)—capable of that. However, most of them, suffer from various drawbacks, such as narrow dissolution windows, hazardous components and poor recyclability, and only a few are feasible in large scale processes. Two commercially successful routes in this context are the viscose and the Lyocell process. The former is based on a carbon disulphide mediated derivatisation of cellulose to form the NaOH(aq)-soluble cellulose xanthogenate and suffers from the hazardous properties of carbon disulfide and the limited mechanical performance of the textile fibres. The latter process relies on cellulose dissolution in a direct non-derivatising solvent N-methylmorpholine N-oxide (NMMO), with the drawback of yielding a chemically unstable, potentially explosive spinning dope and offering fibres with fibrillation issues. For a more sustainable textile production based on wood feedstock, new non–hazardous processes providing a broader range of fibre properties are required, which implies a strong urge to search for new solvent systems for cellulose.

Undoubtedly one of the most attractive alternative systems is NaOH(aq), which has been extensively studied since the early 1930s in terms of dissolution conditions (Davidson 1934; Sobue et al. 1939), dissolution mechanism (Kamide et al. 1992), the structure of the dissolved state (Yamashiki et al. 1988; Roy et al. 2001) and, more recently, additives capable of enhancing the dissolution (Budtova and Navard 2015). In spite of these efforts, the exact mechanism of cellulose dissolution in NaOH(aq) is not fully understood to this day. This study, however, highlights a property of this system that has been overlooked: its inherent ability to capture CO2 due to low temperatures and high alkalinity (Lucile et al. 2012). The presence and action of CO2 in NaOH(aq) during the dissolution of cellulose could be of considerable importance when considering the numerous studies reporting on CO2 as a solvent component or a derivatising agent for cellulose. These include a CO2-mediated synthesis of cellulose carbonate in different solvents as an intermediate step towards improved dissolution in NaOH(aq) (Oh et al. 2002, 2005); dissolution of cellulose in switchable ionic liquids based on interactions between CO2 and strong organic bases (Zhang et al. 2013; Xie et al. 2014) and activation of cellulose by CO2 for a subsequent acetylation (Yang et al. 2015). Moreover, in terms of NaOH(aq), the presence of dissolved CO2 is likely to affect the properties of the solvent system itself by consuming the hydroxide ions in well-known conversions to HCO3 − and CO3 2− (Yoo et al. 2013) and should as such be taken into account. Aqueous hydroxide sorbents, in itself, have been widely studied for direct capture of CO2 from air (Sanz-Pérez et al. 2016), but the only notation of possible effects of CO2 on cellulose in an alkaline aqueous system could be found in a work of Pakshver and Kipershlak, dealing with effects of carbonate ions on xanthogenation and dissolution (Pakshver and Kipershlak 1980).

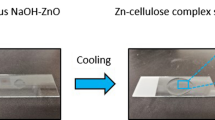

Although no specific incorporation of CO2 in cellulose (such as carbonation) has been reported for aqueous systems, this study—initiated by intricate findings when employing a CO2-capturing superbase as an activator for dissolution of cellulose in NaOH(aq)–points out that possibility. Our early attempts to activate cellulose fibres upon dissolution with the superbase 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) resulted in enhanced swelling/dissolution. As seen in Fig. 1, when DBU was used at a ratio of 0.5 mol per mol AGU, treated fibres were more visibly swelled compared to untreated fibres after 15 min in 8 wt% NaOH(aq) at −5°. Additionaly, an increased tendency of gelation during the actual dissolution process was observed when cellulose was pre-treated with DBU prior to dissolution (see supplementary information). This observation can be indicative of specific cellulose-superbase-CO2 interactions leading to enhanced dissolution and possibly an altered structure of the dissolved state.

Based on the literature and these preliminary findings, the feasibility of cellulose-CO2 interactions occurring in NaOH(aq) at low temperature was investigated. A particular focus was placed on the possible chemisorption of CO2 onto cellulose, reminiscent of a carbonation-like reaction, during dissolution, whereas the questions addressing quantitative effects on dissolution behaviour, dissolved state structure and stability as a consequence of these interactions, as well as the role of DBU will be addressed in upcoming studies. ATR-IR and NMR spectroscopy were used to investigate structural changes upon the dissolution and regeneration of cellulose.

Materials and methods

Materials and chemicals

Microcrystalline cellulose Avicel PH-101, with a degree of polymerisation of 350, was purchased from FMC BioPolymer and used without further treatment. NaOH and 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and also used as received. All other chemicals were purchased from commercial sources and used without further treatment.

Dissolution and regeneration method

Cellulose was dispersed in deionised water with the addition of DBU ranging from 0 to 3 mol DBU per mol AGU to give a final solution concentration of 3 wt% and placed in a refrigerator at +5°C until cool. The pre-cooled cellulose suspension was added to a 30 mL sample tube containing NaOH(aq), with a final solution concentration of 8 wt%, at −5 °C and the mixture was stirred for 1 h. Thereafter, the cellulose dope was quenched and regenerated by the addition of 10 mL ethanol. The precipitate was then washed with ethanol until neutral, filtered off and freeze dried to maintain a porous structure.

Henceforth, the cellulose dissolved and regenerated from NaOH(aq) is referred to as “regenerated cellulose” and the cellulose dissolved and regenerated from NaOH(aq) after pre-treatment with DBU as “pre-treated regenerated cellulose” in the characterisation.

Characterisation

Cellulose and regenerated cellulose samples were examined using Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy collected on a PerkinElmer Frontier equipped with an Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) sampling accessory, PIKE Technologies GladiATR. Samples were placed on top of the ATR crystal and secured using a metal clamp to ensure consistent pressure; they were measured with a resolution of 4 cm−1 and 32 scans. All spectra were corrected against air, normalised to the highest band and shown without an absorbance scale.

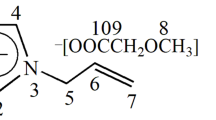

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded using an 800 MHz magnet equipped with a Bruker Avance HDIII console and a CP TXO 800S7 C/N-H-D-05 Z LT cryoprobe. The one-dimensional 13C spectra were recorded using a z-restored spin-echo sequence (Xia et al. 2008) with a relaxation delay (d1) of 3.0 s, at 298 K and a total of 2048 scans. Measurements were recorded for a 30 mg sample in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO d6) with five drops of 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate (EMIMAc) as solvent. EMIMAc was chosen because it dissolves cellulose and shows no chemical shifts in the region of 60–110 ppm, where the cellulose carbon signals appear. It has been reported that the solvent effect of DMSO on the chemical shifts of EMIMAc is minor (Hesse-Ertelt et al. 2010). The chemical structures of cellulose and EMIMAc are shown in Fig. 2, in which cellulose carbons are labelled with a small c for cellulose to distinguish them from the EMIMAc carbons.

Results and discussion

Initial dissolution and regeneration studies

A series of cellulose dissolution experiments with and without DBU pre-treatment was performed, followed by regeneration with ethanol or water. Descriptions of the visual appearance during dissolution and regeneration of all the samples are given in the supplementary information.

The dissolution process of untreated cellulose appeared to differ from that of cellulose pre-treated with DBU, where the latter gave a solution visibly containing gas bubbles and had a tendency to gel much faster than the former during dissolution; when the amount of DBU in the pre-treatment was increased, gelation occurred even faster. In the light of the extensively reported ability of DBU to capture CO2 in the presence of H-donors (Heldebrant et al. 2005, 2008; Jessop et al. 2005; Yang et al. 2011; Mizuno et al. 2012; Carrera et al. 2015; Rajamanickam et al. 2015), these observations could be interpreted as indicative of CO2 interactions with cellulose/NaOH(aq) along with changes in the dissolved state stability.

Indeed, a thermal treatment analysis (monitored by Diffuse Reflectance Infrared Fourier Transform Spectroscopy, DRIFT with mass spectrometry) of one of the pre-treated and ethanol regenerated samples could confirm desorption of CO2 along with water during a temperature ramping (see supplementary information).

Chemical structures of dissolved and regenerated cellulose

The chemical structure of the reference and the regenerated samples was evaluated using ATR-IR and NMR spectroscopy. Figure 3 shows the ATR-IR spectra for the reference cellulose together with the dissolved and ethanol regenerated cellulose (both untreated and DBU pre-treated). The most prominent change in the ATR-IR bands upon DBU pre-treatment, followed by subsequent dissolution and regeneration, was the appearance of a new band at 1593 cm−1. The origin of this band is commonly attributed to a cellulose bound carbonate ion (Zhbankov 1966; Oh et al. 2005) and might indicate the chemisorption of CO2 during the dissolution of cellulose in NaOH(aq) pre-treated with DBU.

Surprisingly, the same carbonate absorption band could be observed for the ethanol regenerated samples dissolved without the DBU pre-treatment. In the case of the DBU pre-treated samples, the band at 1028 cm−1 had a slightly changed intensity, corresponding to the CH2-OH primary alcohol (Santiago Cintrón and Hinchliffe 2015).

Interesting to note was that the samples regenerated with water, displayed in Fig. 4, showed no band at 1590 cm−1 thus suggesting a reversible CO2 chemisorption disfavoured by the extensive addition of water, strongly reminiscent of behaviour of alkyl carbonates (see the discussion below).

Other spectral changes observed relative to the reference sample (e.g. shift of the band arising from the hydrogen-bonded OH from 3331 cm−1 in the reference to 3370–3380 cm−1 in the regenerated samples, as well as the shift and intensity change of the bands at 1315 and 896–899 cm−1) can be attributed to expected crystalline rearrangements from cellulose I to cellulose II upon dissolution and regeneration (Nelson and O’Connor 1964; Oh et al. 2005).

Further studies were carried out using both 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopy. Chemical shifts obtained from 1H to 13C NMR spectra for the solvent, reference cellulose and regenerated samples are shown in Table 1. Figure 5 shows the 13C NMR spectrum for the reference cellulose together with dissolved and ethanol regenerated cellulose (both untreated and DBU pre-treated). A new signal, commonly assigned to a carbonate incorporated in an organic structure (Elschner and Heinze 2015) appeared at 154.3 ppm for the samples regenerated with ethanol, thereby confirming the findings from the ATR-IR spectroscopy analysis. In addition, new signals could be observed at 66.6 and 69.4 ppm in the cellulose area.

Based on previously reported assignments (Kono 2013a, b) of cellulose carbon signals and related intramolecular interactions encountered in derivatives, these new signals could be assumed to originate from the carbons at the 6c (C6c) and 2c (C2c) positions that are affected by the chemisorption of CO2. It is possible that the signal at 66.6 ppm represents the C6c becoming deshielded by the incorporated CO2 (e.g. similar a carbonate-like complex (Kosugi et al. 2000)) and therefore appears at a new shift moved downfield. When the hydrogen bonding between the hydroxyl groups on these carbons is altered, the signal at 69.4 ppm would then be recognised as the C2c, and results in the chemical shift of C2c being moved upfield. The signals at 66.6 and 69.4 ppm are henceforth referred to as C6c’ and C2c’ respectively.

Furthermore, in addition to the new signals in the cellulose area, all carbons in the EMIM cation (EMIM+) were also clearly affected for the ethanol regenerated cellulose samples: exhibiting a new resonance structure and thus indicating specific interaction with the new cellulose structure. Signals at 120.6, 122.5 and 141.5 ppm in particular seemed to be affected significantly by this specific interaction (see supplementary information). The same phenomenon of a new resonance structure was found in the 1H NMR spectra for samples regenerated with ethanol.

Moreover, corresponding cellulose samples regenerated using water show neither the carbonate signal at 154.3 ppm nor the new signals anticipated as originating from the cellulose carbons and EMIM+ structures involved in interactions with CO2 (Fig. 6). This indicates that the incorporation of CO2 into cellulose under the conditions studied is reversible and not favoured when the alkalinity of the system is decreased by the extensive addition of water, which is a behaviour (reported as hydrolysability) expected of alkyl carbonates when brought into aqueous conditions (Franchimont 1910). Regeneration with ethanol, on the other hand, can be assumed to facilitate a fast aggregation of cellulose chains, as it has been shown that dissolved cellulose contracts strongly in alcohol when compared to water (Gavillon and Budtova 2007). This strong contraction could then be the reason for ethanol being able to preserve the chemisorbed CO2 i.e. it does not come into contact with pure water and thereby avoids undergoing the reversible chemisorption process, which could also be observed with ATR-IR spectroscopy.

The origin of the new signals in the cellulose area was investigated with 2D NMR using Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence (HSQC), as this enables the structural assignment of each carbon in the cellulose repeating unit despite overlapping multiplets in the proton spectrum. An example of a HSQC spectrum for a sample regenerated using ethanol is shown in Fig. 7. This spectrum confirms that the new signal at 66.6 ppm couples to protons of a CH2 group with chemical shifts of 3.17 and 3.26 ppm, which are in a reasonable range for protons attached to a substituted C6 and, thus, further supports the implication that this signal originates from a substituted C6c position. Similarly, the signal at 69.4 ppm shows a correlation with a single proton at 3.59 ppm which, in turn, supports the assignment of this signal as a shifted C2c.

Heteronuclear Multiple-Bond Correlation (HBMC) was used in an attempt to investigate a possible correlation between the signal observed at 154.3 ppm, (anticipated as originating from the chemisorbed CO2) and cellulose since it commonly detects correlations across two, three and up to four bonds in conjugated systems arising from so-called long-range couplings. Unfortunately, no coupling was detected between the carbonate signal at 154.3 ppm and any of the carbons that could be seen in the cellulose area, most likely due to weak couplings (Bubb 2003). A minor coupling was nevertheless found between the carbonate signal and the two new signals at 122.7 and 141.7 ppm which, in turn, could be correlated to the new resonance structure for the EMIM+ described above. This new resonance structure is likely to originate from a subsequent chemisorption between EMIMAc and CO2 due to the ability of EMIMAc to form a carbene (Kelemen et al. 2011). These findings indicate that a possible reaction takes place between the cellulose-sorbed CO2 and the EMIM+, yielding a carboxylated EMIM+ with characteristic NMR signals (Besnard et al. 2012; Kortunov et al. 2015) coincident with the signals observed at 154.3 and 141.5 ppm. It is, however, important to bear in mind that the carbonate band seen in the ATR-IR spectroscopy in which no EMIMAc was present shows that the signal at 154.3 ppm does not originate from the EMIMAc but is introduced during the dissolution of cellulose in NaOH(aq).

The new signals detected in the cellulose area could then be interpreted as being either the result of changes in the hydrogen bonding pattern occurring after the reversed chemisorption of CO2 by EMIM+, or the fact that there is a residual CO2 chemisorbed onto the cellulose that affects the chemical shifts in a manner similar to the impact of substitution.

The specific carboxylation reaction between CO2 and EMIM+ has been reported previously by Besnard et al. (2012) and Kortunov et al. (2015), who showed that the signal at 141.5 ppm corresponds to the carboxylated C3 position in EMIM+. The protons at the position H1-H3 in EMIM+, highlighted in Table 1, are also clearly influenced by the carboxylation reaction. This result supports the hypothesis that CO2 is chemisorbed on cellulose during dissolution in NaOH(aq) at low temperature forming a carbonate-like cellulose-CO2 complex that is preserved during subsequent regeneration in ethanol and further rearranged to EMIM+-CO2- cellulose during dissolution in DMSO d6/EMIMAc.

Conclusions

Specific interactions of CO2 with cellulose is a parameter to take into consideration when cellulose is dissolved in NaOH(aq) at low temperature. Although these interactions may be promoted by the presence of so-called “CO2-capturing superbases” (such as DBU), they are generally present in the cellulose/NaOH(aq) system. The chemisorption of CO2 onto cellulose in this solvent system was confirmed by ATR-IR (as a new band in the cellulose spectrum commonly attributed to an organic carbonate-ion) and NMR spectroscopy (a new signal attributed to a carbonate originating from CO2 incorporated in cellulose). The process is reversible, as CO2 desorbs upon regeneration with water. Regeneration with ethanol, on the other hand, preserves the chemisorbed CO2. These results provide new knowledge on the dissolution of cellulose in NaOH(aq) and will be explored further regarding the potential of utilizing cellulose-CO2 interactions to control the dissolution and regeneration processes in this system.

References

Besnard M, Cabaço MI, Vaca Chávez F et al (2012) CO2 in 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium Acetate. 2. NMR investigation of chemical reactions. J Phys Chem A 116:4890–4901. doi:10.1021/jp211689z

Bubb WA (2003) NMR spectroscopy in the study of carbohydrates: characterizing the structural complexity. Concepts Magn Reson Part A 19A:1–19. doi:10.1002/cmr.a.10080

Budtova T, Navard P (2015) Cellulose in NaOH–water based solvents: a review. Cellulose 23:5–55. doi:10.1007/s10570-015-0779-8

Carrera GVSM, Jordao N, Branco LC, Nunes da Ponte M (2015) CO2 capture systems based on saccharides and organic superbases. Faraday Discuss 183:429–444. doi:10.1039/C5FD00044K

Santiago Cintrón M, Hinchliffe D (2015) FT-IR examination of the development of secondary cell wall in cotton fibers. Fibers. doi:10.3390/fib3010030

Davidson GF (1934) The dissolution of chemically modified cotton cellulose in alkaline solutions. Part I—In solutions of sodium hydroxide, particularly at temperatures below the normal. J Text Inst Trans 25:T174–T196. doi:10.1080/19447023408661621

Elschner T, Heinze T (2015) Cellulose carbonates: a platform for promising biopolymer derivatives with multifunctional capabilities. Macromol Biosci 15:735–746. doi:10.1002/mabi.201400521

Franchimont APN (1910) On sodium-alkyl carbonates. KNAW Proc 12:303–304

Gavillon R, Budtova T (2007) Kinetics of cellulose regeneration from cellulose–NaOH–water gels and comparison with cellulose–N-methylmorpholine-N-oxide–water solutions. Biomacromol 8:424–432. doi:10.1021/bm060376q

Hämmerle FM (2011) The cellulose gap (The future of cellulose fibres). Lenzing Ber 89:12–21

Heldebrant DJ, Jessop PG, Thomas CA et al (2005) The reaction of 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) with carbon dioxide. J Org Chem 70:5335–5338. doi:10.1021/jo0503759

Heldebrant DJ, Yonker CR, Jessop PG, Phan L (2008) Organic liquid CO2 capture agents with high gravimetric CO2 capacity. Energy Environ Sci 1:487–493. doi:10.1039/B809533G

Hesse-Ertelt S, Heinze T, Kosan B et al (2010) Solvent effects on the NMR chemical shifts of imidazolium-based ionic liquids and cellulose therein. Macromol Symp 294:75–89. doi:10.1002/masy.201000009

Jessop PG, Heldebrant DJ, Li X et al (2005) Green chemistry: reversible nonpolar-to-polar solvent. Nature 436:1102

Kamide K, Okajima K, Kowsaka K (1992) Dissolution of natural cellulose into aqueous alkali solution: role of super-molecular structure of cellulose. Polym J 24:71–86

Kelemen Z, Holloczki O, Nagy J, Nyulaszi L (2011) An organocatalytic ionic liquid. Org Biomol Chem 9:5362–5364. doi:10.1039/C1OB05639E

Kono H (2013a) 1H and 13C chemical shift assignment of the monomers that comprise carboxymethyl cellulose. Carbohydr Polym 97:384–390. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.05.031

Kono H (2013b) Chemical shift assignment of the complicated monomers comprising cellulose acetate by two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy. Carbohydr Res 375:136–144. doi:10.1016/j.carres.2013.04.019

Kortunov PV, Baugh LS, Siskin M (2015) Pathways of the chemical reaction of carbon dioxide with ionic liquids and amines in ionic liquid solution. Energy Fuels 29:5990–6007. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.5b00876

Kosugi Y, Rahim MA, Takahashi K et al (2000) Carboxylation of alkali metal phenoxide with carbon dioxide at terrestrial temperature. Appl Organomet Chem 14:841–843. doi:10.1002/1099-0739(200012)14:12<841:AID-AOC74>3.0.CO;2-P

Lenzing AG (2015) The global fibre market in 2015. http://www.lenzing.com/en/investors/equity-story/global-fiber-market.html

Lucile F, Cézac P, Contamine F et al (2012) Solubility of carbon dioxide in water and aqueous solution containing sodium hydroxide at temperatures from (293.15 to 393.15) K and pressure up to 5 MPa: experimental measurements. J Chem Eng Data 57:784–789. doi:10.1021/je200991x

Mizuno T, Nakai T, Mihara M (2012) Is CO2 fixation promoted through the formation of DBU bicarbonate salt? Heteroat Chem 23:276–280. doi:10.1002/hc.21014

Nelson ML, O’Connor RT (1964) Relation of certain infrared bands to cellulose crystallinity and crystal latticed type. Part I. Spectra of lattice types I, II, III and of amorphous cellulose. J Appl Polym Sci 8:1097–4628. doi:10.1002/app.1964.070080322

Oh SY, Il Yoo D, Shin Y et al (2002) Preparation of regenerated cellulose fiber via carbonation. I. Carbonation and dissolution in an aqueous NaOH solution. Fibers Polym 3:1–7. doi:10.1007/bf02875361

Oh SY, Il Yoo D, Shin Y, Seo G (2005) FTIR analysis of cellulose treated with sodium hydroxide and carbon dioxide. Carbohydr Res 340:417–428. doi:10.1016/j.carres.2004.11.027

Pakshver AB, Kipershlak ÉZ (1980) Effect of sodium carbonate on the ablilty of cellulose to undergo viscose formation. Khimicheskie Volonka 5:32

Rajamanickam R, Kim H, Park J-W (2015) Tuning organic carbon dioxide absorbents for carbonation and decarbonation. Sci Rep 5:10688. doi:10.1038/srep10688

Roy C, Budtova T, Navard P, Bedue O (2001) Structure of cellulose—soda solutions at low temperatures. Biomacromol 2:687–693. doi:10.1021/bm010002r

Sanz-Pérez ES, Murdock CR, Didas SA, Jones CW (2016) Direct capture of CO2 from ambient air. Chem Rev 116:11840–11876. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00173

Sobue H, Kiessig H, Hess K (1939) The system: cellulose-sodium hydroxide-water in relation to the temperature. Z Phys Chem B 43:309–328

Xia Y, Moran S, Nikonowicz EP, Gao X (2008) Z-restored spin-echo 13C 1D spectrum of straight baseline free of hump, dip and roll. Magn Reson Chem 46:432–435. doi:10.1002/mrc.2195

Xie H, Yu X, Yang Y, Zhao ZK (2014) Capturing CO2 for cellulose dissolution. Green Chem 16:2422–2427. doi:10.1039/C3GC42395F

Yamashiki T, Kamide K, Okajima K et al (1988) Some characteristic features of dilute aqueous alkali solutions of specific alkali concentration (2.5 mol l−1) which possess maximum solubility power against cellulose. Polym J 20:447–457. doi:10.1295/polymj.20.447

Yang Z-Z, He L-N, Zhao Y-N et al (2011) CO2 capture and activation by superbase/polyethylene glycol and its subsequent conversion. Energy Environ Sci 4:3971–3975. doi:10.1039/C1EE02156G

Yang Y, Song L, Peng C et al (2015) Activating cellulose via its reversible reaction with CO2 in the presence of 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene for the efficient synthesis of cellulose acetate. Green Chem 17:2758–2763. doi:10.1039/C5GC00115C

Yoo M, Han S-J, Wee J-H (2013) Carbon dioxide capture capacity of sodium hydroxide aqueous solution. J Environ Manag 114:512–519. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.10.061

Zhang Q, Oztekin NS, Barrault J et al (2013) Activation of microcrystalline cellulose in a CO2-based switchable system. Chemsuschem 6:593–596. doi:10.1002/cssc.201200815

Zhbankov RG (1966) Oxidation products of cellulose. Salts of oxidation products of cellulose. In: Infrared spectra of cellulose and its derivatives. Springer, Boston, MA, pp 117–130. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-2732-3_5

Acknowledgments

This work is part of the framework of Avancell—Center for Fiber Engineering, which is a research collaboration between Södra Skogsägarna and Chalmers University of Technology. The authors are grateful to the Södra Skogsägarna Foundation for Research, Development and Education for their financial support. The Swedish NMR Centre in Gothenburg is acknowledged for performing the NMR measurements. Thanks are due to Mr. Peter Velin for running the DRIFTS experiment and Professor Gunnar Westman for fruitful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gunnarsson, M., Theliander, H. & Hasani, M. Chemisorption of air CO2 on cellulose: an overlooked feature of the cellulose/NaOH(aq) dissolution system. Cellulose 24, 2427–2436 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-017-1288-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-017-1288-8