Abstract

This paper studies consumers’ reactions and resistance to being responsibilized for making climate-friendly food choices. While resistance to consumer responsibilization has been studied from an individual experiential perspective, we examine its collective characteristics. We do this by tracing the controversial marketing campaign of a Swedish poultry producer, encouraging consumers to “do something simple for the climate” by eating chicken rather than beef. In our analysis of social media comments and formal complaints to the consumer protection authority, we mobilize Foucault’s notion of counter-conduct to analyse subtle forms of resistance to consumer responsibilization. We identified four interrelated yet distinct forms of consumer counter-conduct: challenging truth claims, demanding ‘more,’ constructing ‘the misled consumer,’ and rejecting vilification. By theorizing these counter-conducts, we demonstrate how consumers collectively contested both the means and ends of responsibilization—but not the underlying premise of individualized responsibility. Thus, our study helps to explain how consumers’ resistance reproduces, rather than undermines, responsibilization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The notion of responsibility has generated growing interest among researchers of consumer ethicsFootnote 1 (Carrington et al., 2016, 2021; Caruana & Chatzidakis, 2014; Vittel, 2015). Stemming from broader sociological discussions concerning consumerism (Bauman, 2007; Gabriel & Lang, 2015), and informed by a governmentality perspective (Foucault, 2007a, 2007b, 2008), such research has theorized the creation and management of responsible consumer subjects in terms of ‘consumer responsibilization’ (Giesler & Veresiu, 2014; Kipp & Hawkins, 2019). Consumer responsibilization is framed by a neoliberal discourse of individualization (Giesler & Veresiu, 2014; Maniates, 2001), implying consumers are ‘called’ to assume moral responsibilities for societal problems (Shamir, 2008). A pertinent example of this involves consumers reflecting on and managing their consumption in the context of the climate crisis. Correspondingly, consumer responsibilization has been theorized both as a governmental process driven by organizations and institutions (Giesler & Veresiu, 2014) and as a grassroots process driven by consumers (Gollnhofer & Kuruoglu, 2018).

A nascent stream of this literature has focused on how consumers react to or resist responsibilization (Cherrier & Türe, 2022; Eckhardt & Dobscha, 2019; Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021; Soneryd & Uggla, 2015). Consumers have been shown to feel uneasy about responsibilizing interventions (Eckhardt & Dobscha, 2019; Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021) or to negotiate the meaning of responsible consumption (Soneryd & Uggla, 2015). Moreover, responsibilization can trigger opposition about who should take responsibility and for what (Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021), impeding even committed consumers’ enactment of responsibilization (Cherrier & Türe, 2022). To date, research has focused primarily on responsibilization at an individual experiential level. However, as emerging work on grassroots responsibilization demonstrates (Gollnhofer & Kuruoglu, 2018), responsibilization can also emerge through the formation of communities (DuFault & Schouten, 2020; Gollnhofer & Kuruoglu, 2018; Thompson & Kumar, 2021). Following this, we argue that the responsibilization of individual consumers does not occur in a vacuum; rather, it involves consumers interacting and shaping their own and others’ conduct. Yet, we know little about how such collective efforts manifest in reactions and resistance to responsibilizing interventions. Specifically, we need to better understand how consumers mobilize each other as they react to responsibilization attempts, as well as the consequences of such “conduct of conduct” (Foucault, 2007a, 2007b, p. 389). Against this backdrop, we aim to illuminate how consumers relate to others in a “moralized landscape” (Giesler & Veresiu, 2014, p. 843) of responsible consumption. Therefore, we ask: How do consumers collectively contest responsibilization?

The literature on consumer responsibilization builds on a Foucauldian research tradition and an interest in neoliberal consumerist discourses (Giesler & Veresiu, 2014; Yngfalk, 2016), specifically the ‘conducting’ or ‘governing’ of individuals’ (moral) agency through (economic) freedom. Accordingly, germane research is founded on an interest in how power operates. For Foucault, the relation between power and resistance, between conduct and being conducted, is immanent and constitutive (Davidson, 2011; Foucault, 2007a, 2007b). Analysing the governance of consumers as responsible subjects impels an investigation of consumers’ reactions and resistance. To conceptualize how power operates within these contestations, we mobilize Foucault’s (2007a) notion of ‘counter-conduct’ (see also Davidson, 2011). As Foucault states, counter-conduct is not a rejection of being governed but rather a “struggle against the processes implemented for conducting others” (Foucault, 2007a, p. 201). Counter-conduct, therefore, attends to more subtle forms of resistance, compared to revolt or disobedience. Also, counter-conduct lends itself to the purpose of studying collective reactions, with Foucault’s account of the formation of counter-movements in relation to the pastoral power of early Christianity providing a useful analytical frame for this research (Foucault, 2007a).

Empirically, we study how consumers collectively contest responsibilization by analysing a controversial marketing campaign of the Swedish poultry producer, Kronfågel. The campaign—“Do Something Simple for the Climate”—responsibilized consumers to make climate-friendlier dietary choices by switching from eating beef to chicken. Specifically, it compared the emissions saved through such a shift in food consumption to emissions from aeroplane travel, illustrating the greenhouse gas emission-saving potential of the proposed shift. A climate change context is conducive to our research interest regarding the contestation of responsibilization, invoking debates concerning responsibility attribution to different actors, including individuals (Paterson & Stripple, 2010), as well as trade-offs with other environmental and social problems. Accordingly, we traced contestations triggered by this campaign on Kronfågel’s social media page, on several other social media groups, and in formal complaints made by consumers to the Swedish Consumer Agency (a government agency for consumer protection). The manifold and conflicting reactions illustrated consumers’ concerns about three different moral objectives: climate change mitigation, animal welfare, and the role of cattle farming in Swedish agriculture. Studying these online contestations allowed us to analyse arguments and interactions in a setting where consumers are aware that others are reading and responding. Correspondingly, consumers’ “ethical gaze” (Crane, 2005) is not just directed at businesses but also at other consumers and the self.

Using an abductive analysis mobilizing Foucault’s (2007a) notion of counter-conduct, we identified four mechanisms of counter-conduct used by consumers to collectively contest responsibilization: (1) challenging truth claims around responsible consumption; (2) demanding ‘more’ responsible consumption; (3) constructing ‘the misled consumer’; and (4) rejecting vilification of cattle farming. These four counter-conducts, and the responsibility concerns revealed therein, illustrate how consumers took issue with and debated the appropriateness and consequences of the consumption shift proposed by Kronfågel’s campaign.

Our findings and a conceptual shift to counter-conduct contribute to the literature on resistance to consumer responsibilization in two main ways (Cherrier & Türe, 2022; Eckhardt & Dobscha, 2019; Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021; Soneryd & Uggla, 2015). First, we shift the focus from consumers’ individual contestations (Cherrier & Türe, 2022; Eckhardt & Dobscha, 2019; Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021) to collective forms of resistance. We show how four forms of counter-conduct are characterized by engaging others and the formation and mobilization of communities. This has implications for an emergent interest in the role of communities in the context of neoliberal consumer responsibilization (DuFault & Schouten, 2020; Gollnhofer & Kuruoglu, 2018; Thompson & Kumar, 2021). Second, we challenge the assumption that tension around who is responsible and for what is a ‘hurdle’ to consumer responsibilization (Cherrier & Türe, 2022; Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021), explaining how consumers’ collective counter-conduct reifies consumer responsibilization. This has broader implications for consumer responsibilization research (Eckhardt & Dobscha, 2019; Giesler & Veresiu, 2014; Kipp & Hawkins, 2019; Thompson & Kumar, 2021). In contrast to prior studies (Eckhardt & Dobscha, 2019; Thompson & Kumar, 2021), we show how individual responsibility for societal problems remains unchallenged. Instead, consumers collectively contest the knowledge claims used to legitimize responsibilization and the specific consumption choices encouraged. In this way, consumers’ transformation into responsible subjects takes place continuously, despite, or even as a consequence, of their resistance. Thus, consumers’ collective counter-conduct becomes constitutive and immanent to responsibilization. Below, we discuss prior scholarship on resistance to consumer responsibilization, as well as develop our conceptualization.

Consumer Responsibilization and Resistance

Across different disciplines in the social sciences, scholars have used the concept of responsibilization to denote contemporary shifts away from hierarchical governmental authority to more market-like forms of governance (Shamir, 2008; see also Giesler & Veresiu, 2014; Murillo & Vallentin, 2016; Vallentin & Murillo, 2012). Building on the work of governmentality scholars (e.g., Burchell, 1993), Shamir defined it as “a call for action; an interpellation which constructs and assumes a moral agency and certain dispositions to social action that necessarily follow” (2008, p. 4). For Shamir, neoliberal responsibilization is “unique in that it assumes a moral agency which is congruent with the attributed tendencies of economic-rational actors: autonomous, self-determined and self-sustaining subjects” (2008, p. 7). Neoliberal responsibilization is more than a shift of responsibility; it is constitutive of and by neoliberal governmentalities (Foucault, 2007a, 2008), assuming and constructing specific, economic-rational forms of moral agency, for example, through consumption.

Following a constructivist and Foucauldian tradition (Denegri-Knott et al., 2006), consumer and marketing research has understood consumers’ responsibilities as shaped by different actors (Caruana & Chatzidakis, 2014) and discourses (e.g., Caruana & Crane, 2008). Building on this and connecting to ongoing discussions about consumption ethics (Carrington et al., 2016, 2021; Coffin & Egan-Wyer, 2022), studies of responsibility in consumer ethics have explored (both conceptually and empirically) the creation and management of responsible consumer subjects (Bajde & Rojas-Gaviria, 2021; Giesler & Veresiu, 2014; Jagannathan et al., 2020; Kipp & Hawkins, 2019; Mesiranta et al., 2022), whose moral agency is premised on responsible consumption choices. This idea of individualized responsibility through consumption also forms part of what has been referred to as “neoliberal consumerism” (Yngfalk, 2016; Kipp & Hawkins, 2019) or a “neoliberal mythology” (Giesler & Veresiu, 2014).

Consumer responsibilization has been theorized as a “governmental process” comprising four interlinked yet distinct processes driven by authorities, institutions, and organizations; the so-called P.A.C.T routine (Giesler & Veresiu, 2014; Kipp & Hawkins, 2019). First, consumer responsibilization is premised on the idea that societal issues, like climate change, are to be addressed at the individual level (personalization). Second, consumer responsibilization is legitimized by expert knowledge (authorization). Third, it involves the creation of an infrastructure of specific products and services (capabilization). And fourth, based on this “moralized landscape” (Giesler & Veresiu, 2014), consumers possibly alter their choices (transformation). While Giesler and Veresiu (2014) studied responsibilization at the international policy level, other empirical examples include cause-related marketing campaigns by social enterprises (Kipp & Hawkins, 2019) and corporation-NGO partnerships for marketing and CSR purposes (Bookman & Martens, 2013). Although these studies are premised on “power working through practices that make up subjects acting from their own accord” (Bookman & Martens, 2013, p. 289), their emphasis is on the ‘top-down’ shaping of consumer subjectivity – rather than on consumers’ experiences.

Importantly, responsibility is not always attributed ‘only’ to the consumer (e.g., Pellandini-Simányi & Conte, 2021). For example, responsibility for food waste has become increasingly distributed, and shared across a range of different food system stakeholders (Evans et al., 2017; Mesiranta et al., 2022). Indeed, through such expansion of both consumer-centred and shared forms of responsibility, several narratives about who is to be responsible can operate simultaneously (Aschemann-Witzel et al., 2022). Together, these studies outline a more nuanced and dynamic understanding of consumer responsibilization, wherein corporations are also subject to responsibilization.

Yet, responsibility attributions can also occur through consumers’ daily personal experiences of societal issues. Studies illustrate how the personalization of responsibility is transformed into coordination and the formation of responsible collectives or mutual help (DuFault & Schouten, 2020; Gollnhofer & Kuruoglu, 2018; Thompson & Kumar, 2021). To illustrate, grassroots responsibilization can emerge when consumers feel an “urge” to act when exposed to societal issues, such as the refugee crisis in 2015 (Gollnhofer & Kuruoglu, 2018, p. 302). Concomitantly, DuFault and Schouten (2020) illustrate how consumers’ encounters with their low credit scores initiate a journey towards a financially responsible consumer subject, who engages in advice-giving and normative online discussions. Similarly, Thompson and Kumar (2021) show how consumers share experiences and insights about Slow Food, rendering a “collective autonomy” (p. 332) from industrialized food systems. Together, these studies constitute a nascent interest in how responsibilization emerges from engaging with others.

While research shows that the discourse of consumer responsibilization and the ‘responsible consumer’ has been normalized, “related meanings and actions are not direct consequences of it” (Soneryd & Uggla, 2015, p. 914). Consumers may take issue with “what is perceived as a power, a pressure, an influence, or any attempt to act upon one’s conduct” (Roux & Izberk-Bilgin, 2018, p. 295; see also Harrison et al., 2005; Holt, 2002; Kozinets & Handelman, 2004). Reflecting this, a growing stream of scholarship specifically explores how consumer responsibilization is experienced, negotiated, or even opposed (Cherrier & Türe, 2022; Eckhardt & Dobscha, 2019; Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021; Soneryd & Uggla, 2015).

At an experiential level, responsibilization can trigger emotionality (Eckhardt & Dobscha, 2019; Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021). Eckhardt and Dobscha (2019) show that consumers experience physical, psychological, and philosophical discomfort, triggering a rejection of the responsible consumer subject. Reconfiguring consumption practices can make individual consumers feel proud but often also anxious, guilty, or angry (Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021), not least stemming from the tension between wanting to take responsibility and being constrained from doing so (Cherrier & Türe, 2022). Thus, affective responses can underpin both acceptance and rejection of subject positions that consumer responsibilization entails (Bajde & Rojas-Gaviria, 2021; DuFault & Schouten, 2020; Eckhardt & Dobscha, 2019; Gollnhofer & Kuruoglu, 2018; Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021).

Furthermore, this literature shows that consumers negotiate and struggle over who is to take responsibility and for what (Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021; Soneryd & Uggla, 2015). Consumers might negotiate what it means to consume responsibly (Soneryd & Uggla, 2015) or resist calls to become responsible subjects themselves (Eckhardt & Dobscha, 2019; Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021). For example, consumers’ resistance could be a consequence of linking and unlinking different social practices (Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021). Relatedly, Cherrier and Türe (2022) show how an onus to “self-assess” creates substantial consumer ambiguity around choices and their consequences. Thus, prior work has shown how, due to consumers’ reflexivity, specific “call[s] for action” (Shamir, 2008, p. 4) are sometimes accepted (DuFault & Schouten, 2020; Gollnhofer & Kuruoglu, 2018) and, in other cases, contested or resisted (Cherrier & Türe, 2022; Eckhardt & Dobscha, 2019; Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021). Accordingly, previous work has proposed that such struggles or “responsibilization battles” can hinder the enactment of responsibilization (Eckhardt & Dobscha, 2019; Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021).

Overall, extant research has explained different ways in which consumers might resist responsibilization and how this involves consumers’ emotionality (Eckhardt & Dobscha, 2019; Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021), leading to “battles” over who should be responsible and for what (Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021; Soneryd & Uggla, 2015). Arguably, this reflects how consumers attempt to shape a “moralized landscape” (Giesler & Veresiu, 2014) of consumption, negotiating or challenging forms of knowledge used to legitimize responsibilization and the market alternatives on offer to render it possible. We augment this by analytically foregrounding how this takes place in relation to other consumers. Despite emerging interest in collective aspects of responsibilization (DuFault & Schouten, 2020; Gollnhofer & Kuruoglu, 2018), we know little about how consumers react collectively to responsibilization. This is surprising because the very idea of “conduct of conduct” (Foucault, 2007a, p. 389), leading or subtly steering others, is central to a governmentality perspective and, hence, responsibilization. Thus, we argue for a better conceptual understanding of how consumers collectively contest responsibilizing initiatives.

It should be noted that ‘resistance’ in prior consumer responsibilization research comprises neither revolt nor disobedience to hierarchical power. Rather, it is a subtle exercise of power as consumers experience and contest their responsibilization. To conceptualize this subtle struggle, we mobilize Foucault’s (2007a, 2007b) notion of ‘counter-conduct’—a relational and immanent account of resistance and power conducive to analysing collective forms of contestation (Davidson, 2011; see also Foucault, 1982; Heath et al., 2017; McKinlay & Pezet, 2017). We outline this conceptual perspective in the following section.

Conceptual Framework: Counter-Conduct as a Form of Resistance

Foucault argued power moves through “innumerable points of confrontation, focuses of instability, each of which has its own risks of conflict, of struggles, and of an at least temporary inversion of the power relations” (1977, p. 27). He also showed how freedom serves as the ontological basis of power, made possible by the subject’s internalization of a particular regime of truth (Foucault, 2008; Newman, 2021). This, however, implies the possibility of disobedience. As McKinlay and Pezet state, ‘government,’ “is predicated on the assumption that the governed will always adapt, resist, subvert or ridicule the practices of governing, to some degree” (2017, p. 4). Accordingly, resistance is not always a force ‘against’ but can be seen as an inseparable component of power itself (Heath et al., 2017). Foucault argued that “[…] in order to understand what power relations are about, perhaps we should investigate the forms of resistance and attempts made to dissociate these relations.” (Foucault, 1982, p. 780).

In this spirit, Foucault (2007a) introduced the notion of “counter-conduct” (French: contre-conduite), used to describe and analyse how alternative Christian communities developed in opposition to pastoral power in early and Medieval Christianity. It refers to a struggle “against the processes implemented for conducting others” (Foucault, 2007a, p. 201). As such, counter-conduct is not about not wanting to be governed, but rather “how not to be governed like that, by that, in the name of those principles, with such and such an objective in mind and by means of such procedures, not like that, not for that, not by them” (Foucault, 2007b, p. 44; emphasis in original).

Foucault (2007a, pp. 204–215) discussed counter-conduct by referring to five elements of anti-pastoral resistance: asceticism, community, mysticism, scripture, and eschatological beliefs. Arguing that pastoral power, to a large extent, developed as a reaction to ascetic practices of previous times, Foucault showed how the practices of ascesis disrupted the structures of power relations between the pastor and the parish. Here, we understand asceticism as a specific form of the more general notion of self-restraint as an active choice (see also Munro, 2014), disrupting power relations between the governor and the governed.

While asceticism has an individualizing tendency, the second element, community formation, draws on how Christian congregations developed alternative forms of communities dispelling the role of the pastor and his power. Drawing on the notion of being ‘chosen’, these groups let obedience to the pastorate make way for a form of “reciprocal obedience” (Foucault, 2007a, p. 211), where they would obey each other as if obeying God. We suggest this can be understood as reactions that played out through the formation of collectivities based on a form of reciprocal obedience.

Mysticism refers to an experience that escapes pastoral power and its system of truth, building on gradual cumulation and revelation. While the pastor had a central role to mediate communications between the soul and God, mysticism challenges pastoral power as it allows for immediate communication with God. In a broader sense, we reinterpret this as a dismissal of an entrenched knowledge system, building an alternative to escape it.

Foucault also described a return to and emphasis on scripture or biblical text, to short-circuit attempts at pastoral governance. We expand the notion of scripture to include direct engagement with, pointing towards, and drawing upon foundational texts and sources of knowledge. We take this to imply an invocation of a direct relationship to such sources of (true) knowledge, bypassing or calling into question the knowledge claims of the governor.

Finally, the notion of eschatological beliefs refers to a discrediting of the pastor’s role based on God’s eventual return to guide the flock. In a broader sense, we characterize this as the dismissal of the governor in preference to an imminent judgment from a ‘truer’ source of power.

To conclude, first, counter-conduct typifies struggles against processes of being conducted (Foucault, 2007a, p. 201), being directed at a specific type of governmentality. This notion has been used in social movement studies (Death, 2010), organization and management studies (Munro, 2014; Villadsen, 2019), environmental politics (Arifi & Winkel, 2021), and consumer research (Gurova, 2019). While Foucault discussed counter-conduct directed at the Christian pastorate, in more contemporary settings, one can envisage counter-conducts against disciplinary or neoliberal governmentalities. Thus, while the five elements of counter-conduct derive from the situated specifics of pastoral power counter-movements, they offer a vocabulary to inform an analysis of contemporary forms of struggle against government that emphasizes the central role of subjectivity (Munro, 2014). Second, counter-conduct conceptualizes subtle ways of opposing being conducted, a questioning which can shift and re-negotiate the margins of dominant forms of governing. Third, since counter-conduct is an immanent form of contestation, it constitutes ongoing forms of government and “both disrupts and reinforces the status quo” (Death, 2010, p. 235). Against this backdrop, we mobilize Foucault’s notion of counter-conduct as a conceptual lens to explore collective struggles over consumer responsibilization.

Methodology

Research Context

The empirical focus of this study is a marketing campaign by poultry producer Kronfågel and the reactions it triggered. As Sweden’s market leader for chicken, Kronfågel has a range of brands. The 2019 campaign—“Do something simple for the climate” (original: “Gör något enkelt för klimatet”)—built on the climate change mitigation potential of eating chicken (Rågsjö Theorell, 2019). While studying marketing campaigns is not new to the consumer responsibilization literature (e.g., Kipp & Hawkins, 2019), our paper explores the explicit opposition such calls to action may engender. Given the public manifestation of consumers’ backlash, specifically online, this is a useful case to better understand the mechanisms through which consumers collectively oppose responsibilization and to analyse how power operates and becomes productive in such a context.

The different parts of the campaign are presented in Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4 (see below). One segment of the campaign comprised large posters featuring an aeroplane in the sky, and the text “En plan.” ‘Plan’ means both “plan” and “aeroplane” in Swedish, alluding to both plans for climate mitigation and flying. Below the aeroplane, the poster continues: “If everyone who reads this chooses chicken instead of beef only once, it’s like compensating for 14 long-haul jumbo jet flights. Do something simple for the climate tonight. Kronfågel.” At the bottom of the poster, in fine print, is a reference to Kronfågel’s website: “See how we made the calculation at kronfagel.se” (Fig. 1 and 2). A smaller poster communicates that “Chicken has a tenth of the impact on climate compared to beef.” Finally, a 30-s commercial featuring aeroplanes and a family having lunch in their garden, ending with a message like that on the larger poster, was shown on TV and made available by Kronfågel on different social media channels.

Source: https://www.kronfagel.se/hallbarhet/planeten/klimatsmart-mat/ (accessed 9 March 2020)

Excerpt from Kronfågel's website: “Chicken’s impact just a tenth of beef’s”.

Source: https://blogg.landlantbruk.se/enfotimyllan/ Photo: Lena Johansson. (accessed 17 March 2022)

The Kronfågel campaign in the Stockholm subway.

Source: Screenshots from 19 March 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_ldM7xf_ByY (accessed 4 May 2022)

Snapshots from TV advertisement.

The campaign received extensive exposure and contestation—both via social media and the formal procedures of the Swedish Consumer Agency (Konsumentverket). The Swedish Consumer Agency is the Swedish governmental authority responsible for consumer rights, which includes the area of misleading marketing. Also ‘misleading environmental claims’ fall under its auspices (Konsumentverket, 2022). Consumers can lodge formal complaints with the agency, which may initiate a formal investigation under the Swedish Marketing Act.Footnote 2

Collection of Empirical Material

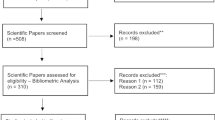

Data collected comprise materials from the campaign itself and reactions to it in the form of documents and social media data. Campaign materials include images of advertisement posters, Kronfågel’s TV commercial posted on YouTube, as well as screenshots of online advertising material from the organization’s website (see Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4). To study the contestations triggered by the campaign, we collected social media comments and official complaints lodged with the Swedish Consumer Agency. As access to information legislation implies that consumers’ formal complaints constitute official documents, we were able to obtain all complaints related to the campaign. In total, we received 92 complaints in the form of digital scans.

As comments from popular media platforms can provide insights into the multiplicity of perspectives and viewpoints on corporate responsibility (Vestergaard & Uldam, 2022), we also traced consumer reactions on social media. As we are interested in resistance and counter-conduct, the critical tone of reactions traced online was not considered problematic. We manually and repeatedly searched several Swedish social media platforms for discussions about the campaign, given the campaign was run in Sweden. We took a broad approach during the collection of empirical data and were interested in any comments discussing the campaign and its content. We retrieved 361 posts and comments from four social media groups and the company’s social media pages from a major platform. These were anonymized and translated from Swedish into English. Data were collected at the beginning of 2020, a few months after the campaign launch, making it possible to trace the initial flurry and gradual reduction of activity on social media. Ongoing contact with the Swedish Consumer Agency indicated that by July 2020 there had been no new complaints for several months. The majority of the 453 complaints and comments were received within two weeks after the campaign launch. Thus, we concluded our data collection. Table 1 provides an overview of the empirical material.

Analysis of the Empirical Material

We used abductive analysis, moving back and forth between the empirical data and our theoretical interests (Schwartz-Shea & Yanow, 2012, p. 28). The analysis comprised three, partly overlapping, iterative phases. In the first phase, we familiarized ourselves with the campaign material, contextualizing it by reading relevant newspaper articles. We analysed Kronfågel’s campaign against the backdrop of consumer responsibilization: Consumers were called to self-manage by choosing chicken, constructed as a climate-friendlier, and thus, more responsible food choice. The campaign message personalized climate change as it called upon consumers to mitigate their food-based greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions through consumption, making the responsible consumer “the central problem-solving agent” (Giesler & Veresiu, 2014, p. 843). Kronfågel legitimized and authorized the ‘call to action’ by providing detailed emission calculations, comparing the emission reduction of switching from beef to chicken to emissions from transportation, namely flying and driving (Giesler & Veresiu, 2014). On Kronfågel’s website, interested readers could follow calculations that transformed counterfactual emissions from beef-not-eaten, aggregated to compare with long-haul flights or miles driven with a car. And, finally, the campaign enabled a call for action, constructing chicken as the more responsible food choice and, thereby, capabilizing consumers by providing them with a seemingly ‘easy’ way to mitigate their GHG emissions (Giesler & Veresiu, 2014).

The second phase of our analysis was driven by an interest to understand the arguments used to contest the campaign. First, we translated all consumer complaints and social media comments, carefully reading and highlighting interesting arguments with different colours. This helped us familiarize ourselves with the empirical material. Thereafter, we undertook a three-stage coding procedure of this material in NVivo, mainly following a segment-by-segment and sometimes line-by-line coding strategy (Charmaz, 2006, pp. 51–53). We initially coded all textual elements in an open manner and next clustered these into broader categories and themes. Throughout this procedure, three empirical themes of contestation emerged: Theme 1 concerned climate change and emission calculation; theme 2 reflected arguments around the animal ethics of chicken production; and theme 3 concerned the agricultural sector in Sweden, specifically the role of cattle farming.

In the third phase, we aimed to better understand how, and through which mechanisms, consumers’ collective resistances occurred across these themes of contestation. As the responsibilization literature and governmentality studies provided our starting points, we typified the manifold forms of power at play in the campaign (through responsibilization) and in consumers’ contestations. To explore the more subtle struggles against being conducted at a collective level in this context of consumer responsibilization, we mobilized the notion of counter-conduct and its elements (Foucault, 2007a). In practical terms, this meant that we explored consumers’ suggestions about “how not to be governed like that” (Foucault, 2007b, p. 44). We were especially attentive to how they expressed concerns about how others would interpret the campaign, and how they attempted to mobilize others in collective complaints. We then arrived at four interrelated but conceptually distinct forms of collective counter-conduct.

We acknowledge that some citizens offering commentary and complaints may have specific interests and backgrounds, such as being involved in farming. For the purposes of our analysis, we considered them to be ‘consumers’ when reacting to the marketing campaign. Relatedly, while consumers might partake in several or only one of the four forms of counter-conduct, it is beyond the scope of the current study to analyse these nuances. Also, as we traced contestations and reactions on social media and formal complaints, our study was confined to observations of forms of counter-conduct constituted by talk or “voice.” We did not observe actions in the form of “exit” (e.g., through anti-consumption or switching to alternatives) (Hirschman, 1970). Rather than seeing this as a limitation, we suggest that such discourse itself is a form of conduct, reflecting the conduct of others and the self.

Findings: Collective Counter-Conduct Against Consumer Responsibilization

In contrast to mandated responsibilizing interventions (cf. Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021), our study focused on a voluntary consumption shift proposed by a marketing campaign. Despite this emphasis on freedom of choice, the campaign provoked vehement reactions, confirming the emotionality of consumer responsibilization (Bajde & Rojas-Gaviria, 2021; Eckhardt & Dobscha, 2019; Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021). We focus, however, on how consumers collectively questioned the precise principles and procedures of consumer responsibilization through four distinct yet interrelated forms of counter-conduct: (1) challenging truth claims, (2) demanding ‘more’ responsible consumption, (3) constructing ‘the misled consumer’, and (4) rejecting vilification of cattle farming. What we show in the following is how consumers collectively resisted responsibilization, calling upon and mobilizing others through these counter-conducts. As part of this, we foreground how consumers actively reflected on how others would interpret the campaign and the negative consequences this would engender, forming responsibilizing communities through counter-conduct. Overall, we show consumers did not question their individual responsibility (cf. Eckhardt & Dobscha, 2019) for making ‘responsible’ food choices in the climate context. Rather, they questioned the means and ends of responsibilization, specifically the knowledge used to legitimize the campaign (i.e., authorization) and the proposed ways for mitigating emissions (i.e., capabilization) (Giesler & Veresiu, 2014).

Challenging Truth Claims: Emissions Calculations, Animal Ethics and Why Beef Is Not That Bad

The first form of counter-conduct involved consumers challenging or de-legitimizing the knowledge base of the campaign, as well as those of other consumers. This counter-conduct underpinned the other three counter-conducts, providing a foundation for taking issue with the campaign in various ways. Like Foucault’s (2007a) accounts of the role of scripture in the context of anti-pastoral resistance, we found that consumers challenged the campaign’s truth claims as they contested and negotiated the meaning of responsible food consumption. The counter-conducts were “outcome-focused” (Carrington et al., 2021, p. 223) in that they revolved around three distinct teleologies: (1) problematic emission comparisons and a too narrow calculative scope, (2) asking for more disclosure about the reality of chicken production, and (3) the proposed positive role of cattle production for the environment. First, consumers questioned the basis of the campaign’s emission calculations and the comparisons it invoked (chicken vs. beef, eating meat vs. flying). A central concern revolved around what was included in the campaign’s calculations and comparisons, and more generally the types of knowledge used to legitimize chicken as a climate-friendly dietary choice. For example, one comment challenged the comparison of different forms of GHG emissions relating to different forms of consumption:

All those comparisons are misleading, and you can’t compare emissions from food consumption with emissions from going by car or flying since they haven’t been measured in comparable ways. I have never seen a calculation for driving that includes roads, garage, tires, motor heater, and everything else that’s part of ‘car culture’. Most of the time, not even the car itself is part of the calculations. (G4-011)

This exemplifies how consumers called into question the use of GHG emissions, as a specific form of knowledge underpinning the campaign’s call for switching from beef to chicken. Concerns about the type of emissions extended to arguments about the origin of emissions (fossil fuels or other sources) and to questions about what was included or omitted in the calculations. Consumers’ questions broadened the scope of ‘responsible consumption’: Did Kronfågel consider that deforestation is connected to soy production, which is often used as feed in large-scale chicken production? What about modes of transportation in the company’s value chains? How does chicken consumption compare to plant-based diets? One source that was frequently brought up was the EAT-Lancet report (Willett et al., 2019), as was the academic journal Science. Sometimes, while still referring to alternative sources of knowledge, comments were sarcastic: “And to switch from chicken to chickpeas, how many long-haul flights does that equal?” (G2-011). Here, many consumers suggested that it was more appropriate to eat plants directly, rather than indirectly through animal-based proteins: “Why not eat the wheat and soy directly instead?” (G4-007) Together, these examples illustrate consumers’ concerns over the type of knowledge mobilized and the GHG emission calculations used to inform the campaign’s ‘call to action’.

Second, consumers challenged the knowledge used or being absent in the campaign’s construction of chicken as a morally superior food choice, linking this to debates over animal ethics. One commentator argued that the campaign “makes the chicken industry seem like a good thing, but it is connected to a range of other environmental problems and—not least—enormous suffering” (G1-008). Ethical problems of industrialized chicken production were also raised in some of the formal complaints. One accused the campaign of being misleading: “they make it seem like an ethical choice to choose chicken, although it is an ethically despicable industry from the animals’ perspective” (KV-035). Another commented, “Millions of chickens kept indoors in an extremely small area cannot be called sustainable! Chickens get sick, walk with broken legs, grow too fast, and have legs that cannot carry their heavy bodies. Ethically objectionable, immoral, unsustainable.” (KV-71). In connection with concerns about animal ethics, some people repeatedly posed questions about the production conditions in Kronfågel’s facilities on the company’s social media page:

How many chickens survive from hatchling to fully grown? The sector should report how high the mortality is among the chickens. (KFSP-165)

How many chickens grow fully and reach the slaughterhouse? Do you keep track of chickens that die along the way? Or is that a hidden number that nobody tracks? They grow abnormally fast and some chickens can hardly walk. (KFSP-169)

These comments act as a call for additional knowledge in the form of more transparency and disclosure, evoking an underlying critique. As such, consumers debated the proposed shift to eating chicken not only from a climate perspective but also by questioning what was ‘known’ about the ethicality of industrial chicken production.

Third, the role of knowledge became relevant as some consumers protested the message to switch from beef to chicken. These comments revolved around why cattle production (and hence beef consumption) is not ‘as bad’ as the campaign might suggest and why the campaign was harmful to the agriculture sector. One such common argument drew on the notion of carbon sequestration, often coupled with a suggestion that beef farming, and associated grazing practices, contributed to biodiversity and open landscapes. Some consumers pointed to so-called regenerative farming practices, arguing that the sequestration of carbon dioxide into the ground (as grass grows back) is larger than the methane emissions from cows’ metabolisms:

Kronfågel, all food production does not have a negative climate impact like your products. Vegetables and beef from regenerative farms contribute to larger carbon sequestration than carbon emissions. So, stop with your ridiculous lies. […]. Pasture-based food production is truly the future! […] (KFSP-16)

Like the above, these social media posts indicate how consumers challenged the campaign’s truth claims, specifically the ‘actual’ climate impact of beef consumption.

In summary, we observed how consumers engaged in ‘challenging truth claims’ connected to the campaign, specifically emission calculations, absent information (e.g., about the health of chickens), and underlying comparisons (e.g., beef and chicken). These knowledge contestations were directed not only at Kronfågel and its campaign, but also at other consumers These comments highlight that consumers did not question their personalized responsibility in addressing climate change through food choices, but rather challenged the authorization of responsibilization (Giesler & Veresiu, 2014). Importantly, what started to emerge and will be elaborated on in the next section, were consumers’ attempts to challenge authoritative knowledge. This manifested in questioning the specific food choices presented as responsible: chicken and its alternatives.

Demanding ‘More’: We Have to Reduce Both Flying and Meat Consumption

A second counter-conduct against the campaign involved questioning the responsibility of certain food choices, specifically eating chicken, along with consumers’ suggestions to ‘do more’—individually and collectively. The campaign triggered debates about what kind of diet was most responsible; it was pointed out that eating chicken did not go far enough, whereas eating a plant-based diet would be a better choice. Others, however, suggested going a step further by reducing both meat consumption and air travel. These general calls for self-restraint were directed at oneself and others for a ‘higher purpose’. This accords with Foucault’s (2007a) ideas about the asceticism of early Christian counter-conducts, specifically self-restraint as an active choice (Munro, 2014) that can disrupt or re-arrange extant power relations. To illustrate, consumers commented in social media groups that there is no space for bad choices, referring specifically to the notion of compensating flights with food choices: “If we are to solve the climate crisis it’s not possible to compensate a bad choice with a good one; we have no room at all for bad choices.” (G1-08).

Relatedly, one complaint to the Swedish Consumer Agency suggested that “[i]n a time when it is necessary that we adopt all means there are to save our planet, it is not right to make people believe that it’s okay to fly more!” (KV-24) Similarly, a comment on Kronfågel’s social media page suggested that the campaign was “misleading”:

It sounds like you can compensate and treat yourself with a vacation flight or a car ride by choosing chicken instead of beef. But we must eat less meat AND stop using fossil fuels at the same time […] but that doesn’t come through, unfortunately, in the ad campaign. (KFSP-124)

Jointly, these comments emphasize consumers’ reflexivity about making climate-friendly consumption choices, as well as calling upon others to act more responsibly. While these arguments were directed at Kronfågel and other consumers, they may also be characterized as acts of work on the self, conveying individual commitment to responsible consumption. They signal that many saw a need to change consumption in different domains, pointing this out to Kronfågel (“your campaign”) and directing such a call to other consumers (“we have to”).

These comments about chicken consumption in relation to other food choices and types of consumer behaviour can be seen as a form of demanding ‘more’ responsible consumption from oneself and others. Here, the means through which responsible consumption was to be achieved (capabilization, see Giesler & Veresiu, 2014) became central, although different knowledge sources fundamentally underpinned these debates. Thus, demanding ‘more’ refers to quantities across different forms of behaviours (eating and flying) and to what consumers conceive as ‘responsible’ consumption.

Constructing ‘The Misled Consumer’: Expressing Concerns for Others

The third counter-conduct relates to the formation of a community of consumers in response to this responsibilization attempt. This community was concerned that the advertisement could mislead ‘others’, who are not ‘knowledgeable’ enough to fully grasp the misleading content and knowledge claims of the campaign. These ‘others’ could take the campaign message at face value, and, therefore, think that their individual chicken consumption could be used to justify flying (capabilization, see Giesler & Veresiu, 2014). We characterize this as consumers constructing the rhetorical figure of ‘the misled consumer’ (Evans et al., 2017) in response to the campaign. Arguably, this active construction of misled ‘others’, who do not understand, can be thought of as the opposite of ‘us’ – the community of those who do understand. Foucault (2007a) explained how alternative (Christian) communities formed in opposition to pastoral power, for example, in the case of the pastor committing a sin. In our case, it was through a collective filing of complaints that these concerns for misled consumers were voiced. When the campaign was launched, the misleading nature of the ad was raised on a social media platform:

I have filed a complaint against Kronfågel for misleading marketing. Feel free to do it yourselves too on the Swedish Consumer Agency’s website. It’s quick, one just fills in a form. […] Kronfågel writes in their ad: ‘If everyone who reads this chooses chicken instead of beef only once, it’s like compensating for 14 long-haul jumbo jet flights. Do something simple for the climate tonight’. The risk with this ad is that the reader may perceive that by choosing chicken instead of beef simply, you can ‘compensate’ for a flight, which, of course, is not correct. On Kronfågel.se, you can read that if 1,224,000 people eat chicken, this is the same as offsetting the emissions from 14 long-haul flights on a jumbo jet. If you, too, think this ad is misleading it’s possible to lodge a complaint on konsumentverket.se [referring to the Swedish Consumer Agency]. (G1-01)

This post acted as a call to mobilize others, based on the perceived misleading nature of the campaign. Others also asked whether “most people” (G1-08) would fully understand that it was not enough for one person to make the switch from beef to chicken. Following the post, discussion erupted, and many agreed, calling the campaign’s comparison a “mistake” (G1-11), “farfetched” (KFSP-128), or “greenwash” (G3-03). Several commented that they had also lodged a formal complaint. A majority of the 92 complaints that were eventually lodged with the Swedish Consumer Agency consisted of a slightly altered version of this original post. A central argument was that “for the person who is not better informed, there’s a risk that you think it’s fine to fly without contributing to climate change, as long as one chooses chicken every now and then instead of beef” (KV-05)—although Kronfågel’s comparison only held if many people switched to chicken. It was also suggested that “[i]f those types of misunderstandings spread it can cause great harm to the environment. A reader must be very observant and fairly creative to interpret the advertisement correctly.” (KV-13) To demonstrate how misleading the message was, someone stated that their “fourteen-year-old son thought the ad was true.” (KV-86).

Arguably, what we see in these contestations is how responsibilization led to the emergence of a collective call to action. Concerned consumers started using similar arguments in their official complaints, sometimes using even the same text, thereby turning against the “misleading” claims of Kronfågel and towards others (e.g., G3-02; KV-05). Moreover, arguments that the campaign was “misleading” led to the formation of a community in opposition to potentially ‘less informed’ others, fearing that “[i]f those types of misunderstandings spread it can cause great harm to the environment.” (KV-13) The basis of this formation was the content of the campaign and how it used calculations and certain ‘truth claims.’ Discontent was directed as much towards Kronfågel as it was towards uninformed ‘others’, who could misunderstand the campaign’s claims.

Several comments also alluded to consumer protection. As some consumers argued on Kronfågel’s social media page, one should not have to “read the fine-print” (KFSP-122) or “click further as a consumer to get adequate information.” (KFSP-146) Relatedly, several people referred to the future impact that complaints to the Swedish Consumer Agency could have on Kronfågel, arguing that:

it should be possible to understand the ad and the information provided in it—without having to go and search further via various links. That’s the law and the law applies to Kronfågel too. The result from the complaints will show that. (KFSP-148, authors’ emphasis)

The above comment points to a belief in imminent judgment, or what Foucault referred to as eschatological beliefs (Foucault, 2007a); other judges and other forms of authority will preside over Kronfågel’s future. In Christian counter-movements, this served as a means of disqualifying the role of the governor (ibid). Consumers called upon Kronfågel to “[d]o the right thing and retract [the campaign] immediately, since it in all likelihood will result in government penalties.” (KFSP-128). Others hoped for even more drastic consequences, encouraging other consumers to make a responsible future choice by boycotting Kronfågel: “Do something good for the environment, replace all meals that would have contained a Kronfågel chicken with vegetarian alternatives and hope the company goes bankrupt.” (KFSP-118).

Rejecting Vilification: Accusing Kronfågel of ‘Finger Pointing’ at Cattle Farming

The fourth and final counter-conduct relates to concerns for the consequences of the campaign’s message for others, particularly other forms of agriculture, primarily cattle farming. We found consumers formed a community in opposition to attempts to construct beef as a harmful consumption choice (capabilization, see Giesler & Veresiu, 2014) and the truth claims the responsibilization campaign was based on. Like the above concern for other (possibly misled) consumers, our interpretation of this was also informed by Foucault’s (2007a) account of the formation of alternative communities to circumvent pastoral forms of governing. Several commentators explicitly compared Kronfågel’s campaign with oat milk producer Oatly’s recent campaign to “ditch the milk.” As theorized elsewhere (Koch & Ulver, 2022), Oatly’s marketing activities built on “negative amplification of the status quo industry” (ibid., p. 256) to legitimize oat milk. This led to a high-profile conflict with dairy producer, Arla (Goldberg, 2019). Thus, the Oatly analogy signalled discontent with Kronfågel’s way of advertising chicken by describing beef as an inferior alternative. The following post on Kronfågel’s social media page indicates this:

So, like Oatly you talk shit about another branch of agriculture. That’s what you do when you can’t stand on your own merit, but you should be ashamed. (KFSP-46)

Thus, these comments accuse Kronfågel of ‘finger pointing’ by depicting beef consumption as an irresponsible choice in comparison to chicken consumption. Many asserted several versions of how “both Kronfågel and Oatly should be ashamed” (KFSP-25) and that they “should be able to stand on their own merit” (KFSP-27). Protecting Swedish agriculture through collaboration, rather than shaming or vilification, was also voiced as an important objective:

Without beef/milk production you can say goodbye to Swedish grains for our chickens—everything is connected. The agriculture business is connected through different branches that are dependent on each other. (KFSP-199)

A key line of reasoning was that Swedish agriculture needed protection and collaboration. Specific products, such as beef, should not be depicted as the less responsible alternative: “Bad argument—it is definitely wrong to compare Swedish foods in this manner. It’s like comparing apples and pears!!” (KFSP-250). Thus, through this counter-conduct, which we term rejecting vilification, we see how commentators start proposing a need for collaboration in Swedish agriculture and collectively opposing what is described as “smearing” (e.g., KFSP-194; KFSP-44), “attacks” (KFSP-163; KFSP-221; “dirty tricks” (KFSP-27) and “talking shit” (KFSP-86) by Kronfågel. This counter-conduct aligns with constructing ‘the misled consumer’ in its concern for others and the resulting community formation.

Related to this, many suggested that farmers should “stick together” (KFSP-94), alluding to the judgment that would eventually befall Kronfågel from their “own suppliers” (KFSP-243). One person asked: “Don’t farmers make up 95% of Kronfågel’s growers? Do they accept throwing dirt on their colleagues’ cattle???” (KFSP-88). Instead of accepting the division between chicken breeding and cattle rearing implied by the comparison of climate impact, comments referenced community relationships between different types of farmers:

As I work with farmers across all branches of production, I know it’s a very collegial profession. Therefore, I have real difficulties with you jumping on this bandwagon against beef suppliers. I think most farmers know that all branches are needed for our environment, our open landscapes, and for our diversity. And I hope most consumers understand that too. I honestly think this advertisement does more harm than good from an environmental perspective. And you have lost everyone in my family as customers. (KFSP-241)

As with the previous counter-conduct, a community was formed—but one inviting a form of future ‘judgement’ as farmers, specifically in their role of suppliers, unite and turn against Kronfågel.

Discussion

Based on our counter-conduct lens, we have shown how consumers reacted to attempted responsibilization through four distinct yet interrelated counter-conducts. Consumers challenged the truth claims of the campaign and those made by others, which underpinned the other three counter-conducts. Together with demanding ‘more’ responsible consumption, consumers called others and the self to action. Moreover, consumers formed communities in opposition to the responsibilization initiative by constructing ‘the misled consumer’ and by rejecting vilification of cattle farming.

We found that the counter-conduct lens provides new ways of understanding mechanisms of resistance to consumer responsibilization because it is sensitive to the constitutive relation between power and resistance. What was at stake in reactions against Kronfågel’s campaign was not the ascription of individual responsibility for ‘appropriate’ consumption choices (cf. Eckhardt & Dobscha, 2019; Giesler & Veresiu, 2014). Instead, we observed how consumers collectively shaped a “moralized landscape” (Giesler & Veresiu, 2014, p. 843) of responsible food choices through counter-conduct. Prior work has observed consumer scepticism towards organizations for their ‘true’ motivation behind responsibilizing consumers (Bookman & Martens, 2013; Eckhardt & Dobscha, 2019; Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021). Rather, we find scepticism towards the knowledge claims mobilized and the operationalization of the campaign as a calculation-based comparison, and the proposition that chicken is a responsible food choice and the consequences of this for others. Thus, our study is not about a rejection of being conducted; the counter-conduct perspective emphasizes how individuals collectively challenged the legitimization of responsibilization and the consumption choices it encouraged.

Figure 5 illustrates how collective counter-conduct reproduces consumer responsibilization, by relating it to the P.A.C.T routine (Giesler & Veresiu, 2014). In our study, personalization remains stable and unchallenged as consumers did not question being ascribed individual responsibility (hence the solid line in the Figure). However, through collective counter-conduct, consumers took issue with the precise authorization and capabilization of the campaign (hence the dotted and sketched lines). We propose that this active and critical engagement together with the implied acceptance of personalization constituted a vehicle for consumers’ continuous transformation into responsible consumer subjects (depicted by continuous arrows encompassing all steps). In this manner, responsibilization was reproduced (ibid.; Kipp & Hawkins, 2019). Below, we outline our contributions to the extant literature in more detail.

Source: Authors’ adaptation of Giesler and Veresiu (2014)

Reproduction of consumer responsibilization through collective counter-conduct. Note: Solid and dotted lines depict that these steps of consumer responsibilization were unchallenged and challenged respectively.

First, we contribute to the literature concerning resistance to consumer responsibilization (Cherrier & Türe, 2022; Eckhardt & Dobscha, 2019; Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021; Soneryd & Uggla, 2015) through a shift in theoretical focus. We shift the analytical gaze from individual and experiential aspects of resistance, as theorized in the extant literature, to a consideration of resistance as a collective endeavour. Specifically, previous work has focused on how individuals have grappled with obstacles and hindrances imposed on them by a responsibilizing intervention (Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021) and/or the challenges of prioritizing different responsibilities (Cherrier & Türe, 2022). In comparison, our study has illustrated such struggles as collective reactions wherein committed consumers actively seek to responsibilize others.

On the one hand, consumers engaged in collective forms of resistance by calling upon others to act more responsibly or to counter a responsibilizing intervention. We observed this in the active challenging of truth claims raised in both the campaign and by other consumers, demanding ‘more’ responsible consumption. Our theorization of these ‘calls’ contributes to a refining of our understanding of how consumers relate to the notion of responsibility. Gonzalez-Arcos et al. (2021) discussed ‘clashes over who is responsible’, which distract consumers from changing their practices and make them reluctant to change unless they see a commitment from others. We further nuance such clashes by illustrating how already responsibilized consumers actively and vocally signalled their commitment and sought to responsibilize others and themselves—rather than abrogating their responsibility.

On the other hand, we observed consumers interacting to form responsibilizing communities by rejecting vilification and constructing ‘the misled consumer.’ This manifests a central theme in our findings; a concern for the campaign’s consequences for ‘others.’ Extant studies outline how ‘committed’ consumers may avoid participating in sustainability interventions (e.g., waste recycling) due to concerns that these could be destructive (e.g., for the environment, see Cherrier & Türe, 2022). We build on this insight by showing how such destructiveness is construed, not only in relation to one’s own consumption practices (given the extant literature’s focus on the individual), but also in relation to the imagined actions of, and consequences for, constructed ‘others.’ It is through this othering, in the form of others who are either misled or vilified by the comparison, that consumers form communities. Yet we do not prescribe how to interpret these concerns for ‘others.’ Indeed, the notion of ‘concern’ is inherently ambiguous, with the potential for both ‘care’ and ‘condescension’. Here, a central concern was the consequence of the campaign on consumers’ choices, particularly how the campaign message could be used to justify or promote irresponsible practices. Linked to this, there was a looming threat that the formation of communities will adversely affect the corporation. Stakeholders (particularly suppliers and customers) may turn against the corporation and ‘judgement’ for an inappropriate and misleading campaign may ensue from the regulator.

With these insights regarding how consumers collectively counter-conduct responsibilization, we also speak to emergent interests in the collective formations and implications of neoliberal consumer responsibilization (DuFault & Schouten, 2020; Gollnhofer & Kuruoglu, 2018; Thompson & Kumar, 2021). Prior work has shown how societal crises render individual ‘urges’ for consumers to get involved and to assume responsibility on a personal level (Gollnhofer & Kuruoglu, 2018). We demonstrate that such ‘urges,’ and the resultant formation of communities, can also arise when a responsibilizing intervention is experienced as inadequate and inappropriate. In this light, our study also demonstrates the important role of sharing experiences, skills, and expertise in contestations (DuFault & Schouten, 2020; Thompson & Kumar, 2021). While we confirm the central role of knowledge in collective responsibilization processes, we emphasize how consumers contest and mobilize knowledge claims to construct morally superior choices and morally superior communities.

Second, we contribute to research on consumers’ resistance and reactions to responsibilization (Cherrier & Türe, 2022; Eckhardt & Dobscha, 2019; Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021). We do so by showing how counter-conduct reproduces responsibilization rather than hindering or challenging it. Previous work has theorized resistance to consumer responsibilization as negotiations (Soneryd & Uggla, 2015), tensions (Cherrier & Türe, 2022), or a set of challenges to practice change (Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021). Research has observed that consumers might confront tensions resulting from conflicting or superimposing responsibilities, i.e., the “multiple and conflicting responsibilities that [consumers] struggle to prioritize” (Cherrier & Türe, 2022, p. 7). Moreover, research has pointed out that consumers’ scrutiny of implications and trade-offs associated with different sustainability interventions can become a “challenge” to responsibilization, hindering changes in practices (Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021, p. 47). In contrast to these studies, we do not characterize tensions as barriers to responsibilization but argue that consumers’ counter-conduct reinforces rather than detracts from responsibilization (cf. Gonzalez-Arcos et al., 2021). Importantly, collective counter-conduct expands and alters the notion of responsibility. This is in line with Foucault’s (2007a) observation that different elements of counter-conduct altered the “general horizon of Christianity” as some “border elements” and practices stemming from counter-movements were continually “re-utilized, re-implanted, and taken up again” by the church (Foucault, 2007a, p. 215).

Our findings have implications for consumer responsibilization more broadly (Giesler & Veresiu, 2014; Kipp & Hawkins, 2019), by showing that personalization remains unchallenged rather than rejected (Eckhardt & Dobscha, 2019) or evaded (Thompson & Kumar, 2021). What we mean by this is that throughout the reactions, the campaign's construction of the consumer subject as the "central problem-solving agent" (Giesler & Veresiu, 2014, p. 843) was not called into question. Thus, our study elaborates and provides empirical ‘flesh’ to the theoretical postulation by Soneryd and Uggla (2015): Even the rejection of certain aspects of the notion of ‘responsible consumption’ constitutes a form of active participation in the practices of governmentality giving “form and effect to presupposed subject positions” (ibid., p. 926).

Our insights into how collectivities construct and reify the axis of ‘reciprocal obedience’ are central to an analysis of the recursive relation between resistance and consumer responsibilization. We observed how consumers took issue with “pastoral power” (Foucault, 2007a) by questioning the campaign but, moreover, conducting others and themselves as they questioned the means and ends of responsibilization. While extant research differentiated between governmental (see Giesler & Veresiu, 2014; Kipp & Hawkins, 2019) and grassroots (see Gollnhofer & Kuruoglu, 2018) processes of responsibilization, our study importantly illustrates how they can be intertwined. We offer an account of the relational and manifold ways in which power unfolds at the intersection of governmental responsibilization (the campaign) and grassroots responsibilization through counter-conduct (the reactions). Counter-conducts are not “additional or reactive mechanisms,” but “immanent and necessary to the formation and development of governmentality” (Cadman, 2010, p. 140). Ultimately, we show how collective counter-conduct reproduces rather than undermines the status quo of individualized responsibility (Death, 2010; Heath et al., 2017).

Concluding Remarks, Limitations, and Suggestions for Future Research

Our study has illustrated a case of “pressures at the corporate–consumer interface” (Caruana & Chatzidakis, 2014, p. 578) and, thereby, broadly speaks to scholarship on consumer responsibility (Caruana & Chatzidakis, 2014; Vittel, 2015) and the central issue of power in this context (Fuchs et al., 2016). Specifically, the campaign offers insightful perspectives on the communicative strategies underpinning the creation of consumers as responsible, active subjects through Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) communication or marketing campaigns (Crane & Glozer, 2016). We have also connected to broader debates within consumer ethics (Carrington et al., 2016, 2021), specifically recent work on the “ethical consumption cap,” which proposes that the overwhelming complexity and shifting nature of interlinked sustainability issues make it difficult for consumers to act in accordance with their values and intentions (Coffin & Egan-Wyer, 2022; see also Cherrier & Türe, 2022). Beyond this, our case has reflected on how the climate crisis is not only entangled with multiple sustainability issues but also with livelihoods and identities. We illuminated how the role of knowledge regulates and shifts “social and ‘felt’ norms,” and how the construction and negotiation of these take place in a multitude of directions in online settings (Carrington et al., 2021, p. 234). Future studies could continue using social media to study the power relations revealed through contestations over sustainability communications and their consequences (Crane & Glozer, 2016).

Our findings also have practical contributions. The marketplace has become central to responsibilization (Shamir, 2008) and the emergence of responsible consumer choices. However, our study provides a ‘cautionary tale’ for firms mobilizing climate change in their CSR communication and marketing. Even if marketers get the facts and figures ‘right,’ comparisons of different forms of climate mitigation (here food consumption and flying) are problematic. In a setting where consumers are called to manage their consumption, and where such calls are authorized through expert knowledge, it is perhaps not unexpected that consumers also mobilize different forms of (counter) knowledge. Although concerned consumers might not necessarily resist calls to take individual responsibility, they might be sceptical of win–win narratives and voice their scepticism with increasingly sophisticated and highly polarized arguments, for example, in online settings.

The scope of our analysis also implies certain limitations for our understanding of responsibilization and its resistance. While our study contained processual elements, specifically consumers’ reactions in response to responsibilization, future research could explore in more detail how the dynamics between responsibilization and these counter-conducts unfold over time. Another possible extension of our work would incorporate comparative elements based on two or more contested responsibilizing interventions. The literature has shown how both mandatory and voluntary initiatives can produce strong, emotional reactions, and a fruitful avenue for future research would specifically address whether there are other differences between these initiatives. In sum, we suggest that counter-conduct provides a helpful analytical repertoire to trace more subtle forms of opposition to governing. Future research could explore how different forms of counter-conduct relate to, and play out in, other areas of consumption and beyond. Furthermore, counter-conduct can be used to further disentangle how reactions to neoliberal consumer responsibilization can be simultaneously atomistic and relational.

Data availability

For the preservation of anonymity, the empirical data are not available to be shared.

Notes

Consumer ethics and related terms (such as ethical consumption) are often used interchangeably—although there are differences. See Carrington et al. (2021) for a comprehensive literature review.

The Swedish Marketing Act, Marknadsföringslag (2008: 486), is applicable to marketing of goods and other products, with the purpose of counteracting undue marketing, including misleading marketing. Regarding environmental claims, there is also a specific EU directive and guidance, which is implemented in Sweden through the Marketing Act.

References

Arifi, B., & Winkel, G. (2021). Wind energy counter-conducts in Germany: Understanding a new wave of socio-environmental grassroots protest. Environmental Politics, 30(5), 811–832.

Aschemann-Witzel, J., Randers, L., & Pedersen, S. (2022). Retail or consumer responsibility?—Reflections on food waste and food prices among deal-prone consumers and market actors. Business Strategy and the Environment. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3202

Bajde, D., & Rojas-Gaviria, P. (2021). Creating responsible subjects: The role of mediated affective encounters. Journal of Consumer Research, 48(3), 492–512.

Bauman, Z. (2007). Consuming life. Polity Press.

Bookman, S., & Martens, C. (2013). Responsibilization and governmentality in brand-led social partnerships. Social Partnerships and Responsible Business (pp. 288–305). Routledge.

Burchell, G. (1993). Liberal government and techniques of the self. Economy and Society, 22(3), 267–282.

Cadman, L. (2010). How (not) to be governed: Foucault, critique, and the political. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 28(3), 539–556.

Carrington, M., Chatzidakis, A., Goworek, H., & Shaw, D. (2021). Consumption ethics: A review and analysis of future directions for interdisciplinary research. Journal of Business Ethics, 168(2), 215–238.

Carrington, M. J., Zwick, D., & Neville, B. (2016). The ideology of the ethical consumption gap. Marketing Theory, 16(1), 21–38.

Caruana, R., & Chatzidakis, A. (2014). Consumer social responsibility (CnSR): Toward a multi-level, multi-agent conceptualization of the “other CSR.” Journal of Business Ethics, 121(4), 577–592.

Caruana, R., & Crane, A. (2008). Constructing consumer responsibility: Exploring the role of corporate communications. Organization Studies, 29(12), 1495–1519.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory. Sage.

Cherrier, H., & Türe, M. (2022). Tensions in the enactment of neoliberal consumer responsibilization for waste. Journal of Consumer Research. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucac037

Coffin, J., & Egan-Wyer, C. (2022). The ethical consumption cap and mean market morality. Marketing Theory, 22(1), 105–123.

Crane, A. (2005). Meeting the ethical gaze: Challenges for orienting to the ethical market. In R. Harrison, T. Newholm, & D. Shaw (Eds.), The ethical consumer (pp. 219–223). Sage.

Crane, A., & Glozer, S. (2016). Researching corporate social responsibility communication: Themes, opportunities and challenges. Journal of Management Studies, 53(7), 1223–1252.

Davidson, A. I. (2011). In praise of counter-conduct. History of the Human Sciences, 24(4), 25–41.

Death, C. (2010). Counter-conducts: A Foucauldian analytics of protest. Social Movement Studies, 9(3), 235–251.

Denegri-Knott, J., Zwick, D., & Schroeder, J. E. (2006). Mapping consumer power: An integrative framework for marketing and consumer research. European Journal of Marketing, 40(9), 950–971.

DuFault, B. L., & Schouten, J. W. (2020). Self-quantification and the datapreneurial consumer identity. Consumption Markets & Culture, 23(3), 290–316.

Eckhardt, G. M., & Dobscha, S. (2019). The consumer experience of responsibilization: The case of Panera Cares. Journal of Business Ethics, 159, 651–663.

Evans, D., Welch, D., & Swaffield, J. (2017). Constructing and mobilizing ‘the consumer’: Responsibility, consumption and the politics of sustainability. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49(6), 1396–1412.

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. Vintage Books.

Foucault, M. (1982). The subject and power. Critical Inquiry, 8(2), 777–795.

Foucault, M. (2007a). Security, territory, population. Lectures at the Collège de France 1977–1978. Picador.

Foucault, M. (2007b). What is critique. In S. Lotringer (Ed.), The politics of truth (pp. 41–81). Semiotext(e).

Foucault, M. (2008). The birth of biopolitics. Lectures at the Collège de France 1978–1979. Picador.

Fuchs, D., Di Giulio, A., Glaab, K., Lorek, S., Maniates, M., Princen, T., & Røpke, I. (2016). Power: The missing element in sustainable consumption and absolute reductions research and action. Journal of Cleaner Production, 132, 298–307.

Gabriel, Y., & Lang, T. (2015). The unmanageable consumer. Sage.

Giesler, M., & Veresiu, E. (2014). Creating the responsible consumer: Moralistic governance regimes and consumer subjectivity. Journal of Consumer Research, 41(3), 840–857.

Goldberg, J. (2019, December 4). Sweden’s ‘milk war’ is getting udderly vicious. The Future. Retrieved 17 Mar 2020 from https://theoutline.com/post/8384/sweden-milk-war-oatly?zd=2&zi=olo3naol.

Gollnhofer, J. F., & Kuruoglu, A. P. (2018). Makeshift markets and grassroots responsibilization. Consumption Markets & Culture, 21(4), 301–322.

Gonzalez-Arcos, C., Joubert, A. M., Scaraboto, D., Guesalaga, R., & Sandberg, J. (2021). “How do I carry all this now?” Understanding consumer resistance to sustainability interventions. Journal of Marketing, 85(3), 44–61.

Gurova, O. (2019). Patriotism as creative (counter-)conduct of Russian fashion designers. Consumer Culture Theory, 20, 151–168.

Harrison, R., Newholm, T., & Shaw, D. (Eds.). (2005). The ethical consumer. Sage.

Heath, T., Cluley, R., & O’Malley, L. (2017). Beating, ditching and hiding: Consumers’ everyday resistance to marketing. Journal of Marketing Management, 33(15–16), 1281–1303.

Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, voice, loyalty: Response to decline in firms, organizations, and states. Harvard University Press.

Holt, D. B. (2002). Why do brands cause trouble? A dialectical theory of consumer culture and branding. Journal of Consumer Research, 29(1), 70–90.

Jagannathan, S., Bawa, A., & Rai, R. (2020). Narrative worlds of frugal consumers: Unmasking romanticized spirituality to reveal responsibilization and de-politicization. Journal of Business Ethics, 161, 149–168.

Kipp, A., & Hawkins, R. (2019). The responsibilization of “development consumers” through cause-related marketing campaigns. Consumption Markets & Culture, 22(1), 1–16.

Koch, C. H., & Ulver, S. (2022). PLANT VERSUS COW: Conflict Framing in the Ant/Agonistic Relegitimization of a Market. Journal of Macromarketing, 42(2), 247–261.

Konsumentverket. (2022). Om Konsumentverket. Retrieved 13 Oct 2022 from https://www.konsumentverket.se/om-konsumentverket/var-verksamhet/miljo-och-hallbar.

Kozinets, R. V., & Handelman, J. M. (2004). Adversaries of consumption: Consumer movements, activism, and ideology. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(3), 691–704.

Maniates, M. F. (2001). Individualization: Plant a tree, buy a bike, save the world? Global Environmental Politics, 1(3), 31–52.

McKinlay, A., & Pezet, E. (2017). Foucault and managerial governmentality: Rethinking the management of populations, organizations and individuals. Routledge.

Mesiranta, N., Närvänen, E., & Mattila, M. (2022). Framings of food waste: How food system stakeholders are responsibilized in public policy debate. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 41(2), 144–161.

Munro, I. (2014). Organizational ethics and Foucault’s ‘art of living’: Lessons from social movement organizations. Organization Studies, 35(8), 1127–1148.

Murillo, D., & Vallentin, S. (2016). The business school’s right to operate: Responsibilization and resistance. Journal of Business Ethics, 136(4), 743–757.

Newman, S. (2021). Power, freedom and obedience in Foucault and La Boétie: Voluntary servitude as the problem of government. Theory, Culture & Society, 39(1), 123–141.