Abstract

Research into spirituality and its impact on the work environment has been bourgeoning. In an attempt to explore the role of Islamic spirituality in the workplace, this study examines the influence of Islamic spirituality on job satisfaction and organisational commitment through work ethics. Data are obtained by an online Likert-scaled questionnaire survey based on one thousand Muslim employees from various economic sectors in Indonesia and analysed through structural equation modelling (SEM). The findings demonstrate that Islamic spirituality positively influences job satisfaction and organisational commitment as two dimensions of work attitudes and that work ethics mediate that influence. There is also evidence that job satisfaction positively influences organisational commitment, but work ethics does not moderate that influence. The findings related to the role of work ethics, which mediates the effect of Islamic spirituality on job satisfaction and organisational commitment, can be considered the contribution of this study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Research in spirituality and its impact on work ethics and workplace performance has been growing rapidly, predicated on the assumption that human attitude to work is affected by innate spirituality (Ashmos & Duchon, 2000). Integrating spirituality with work creates a deeper meaning of the tasks by providing strong values to support positive attitudes in the workplace (Cavanaugh, 1999; McCormick, 1994; Mitroff & Denton, 1999). It is also argued that aligning spirituality and work benefits both individual and organisation (Lips-Wiersma, 2002).

The existing literature reveals that spirituality has become an important topic (see: Miller, 1998; Konz & Ryan, 1999; Mitroff & Denton, 1999; Ashmos & Duchon, 2000; Tischler et al., 2002; Dean et al., 2003; Neal & Biberman, 2003; Duchon & Plowman, 2005; Klerk, 2005; McGhee & Grant, 2008). As part of such emerging literature, organisations are considered to include and facilitate the spiritual dimension despite being rational systems.

Spirituality is generally linked to religion, but there are important nuances; religion, grounded in beliefs, values and practices, refers to formal conditions and is often general, whereas spirituality as a state or manner of being is associated with wishing to experience divine power. Additionally, religion includes behaviourisms, while spirituality is associated with feelings of positivity concerning the environment an individual occupies. However, religious practices may moderate spirituality and vice versa (Barnett et al., 2000). Some individuals can be both simultaneously (Aburdene, 2005). For instance, Islam places a strong emphasis on spirituality and expects spirituality to cover life in everydayness (Nasr, 1985b, 2008), including in the workplace (Kinjerski & Skrypnek, 2004; Mitroff & Denton, 1999).

Considering the increased importance attached to spirituality in the workplace, recent developments in spirituality studies consider spirituality a driver for business optimisation. This trend appears proven by the emergence of three spiritual generations in business (Pradiansyah, 2007). Firstly, the pre-spirituality generation believed that business is about profit; the second generation has accepted but not embedded spirituality in business, while the third fully understands and embeds spirituality in the workplace.

This study, therefore, aims at empirically examining the mediation and moderation impact of Islamic spirituality on job satisfaction and organisational commitment among Indonesian employees, whereby the importance of spirituality in the development of employee performance is examined. In this, job satisfaction and organisational commitment are considered as dimensions of two kinds of work attitudes, while work ethics plays the mediation and moderation impact. Accordingly, it is assumed that Islamic work ethics can function as a key factor in enhancing the organisational quality and contribute to its performance (Aldulaimi, 2016; Kalemci & Tuzun, 2019). This research is, therefore, predicated on the assumption that employees who embrace spirituality may demonstrate a better performance, which, as a hypothesis, is tested in this study.

In identifying the contribution, and hence the novelty, of this study and the distinction it makes, it should be stated that in its conceptualisation, this study modifies the previous research by placing Islamic spirituality, which incorporates individual and organisational spirituality in one construct as an independent variable and work ethics as mediating and moderating variable. The modification is based on the fact that religiosity and spirituality almost always significantly influence the attitude and behaviour of individuals and that those two potentially affect organisations (King & Crowther, 2004). Therefore, in this empirical study, religiosity is defined as Islamic spirituality.

Concerns relating to the interaction between an individual’s spirituality and organisational commitment provide the impetus for this study. While extensive research on Islamic spirituality is available within Islamic studies and philosophy (see: Nasr, 1985a, 1985b, 2008; Gümüşay, 2012) and business and work ethics (see among others: Aldulaimi, 2016, Athar et al., 2016; Anwar et al., 2020; Beekun, 1997; Choudhury, 2020; Gheitani et al., 2019; Hassi et al., 2021; Kalemci & Tuzun, 2019; Ab et al., 2016), this study contributes to the literature by collaborating spirituality, work ethics and work attitudes in the workplace from an Islamic perspective. According to the results established in the literature, individual spirituality negatively affects work attitudes, but it can change to be positive if the workplace embeds organisational spirituality. Such anomaly then needs to be re-assessed. On the other hand, the concept of spirituality in Islam includes individuals and organisations, meaning that both are not necessarily separated due to the Islamic worldview of tawhid in the sense of complementarity within unitarity (Asutay, 2013; Choudhury, 2020). The Islamic approach in this conceptualisation considers the influence of religiosity as a mechanism to comprehend the magnitude of individual and organisational attitudes towards job satisfaction and organisational commitment. This study opted for a case where religiosity is expressed in everyday life, including the workplace; thus, a sample of Indonesian Muslim employees was selected.

The spirit to practice religiosity is witnessed by the expansion of Shari’ah-based industries, such as halal markets and Islamic finance. Studying spirituality and its impact on ethics and attitudes generates knowledge regarding optimising employee and company performance. This study assumes that employees who embrace Islamic spirituality can achieve better job satisfaction and develop a positive and effective work attitude translating into organisational commitment (Athar et al., 2016). Furthermore, it is argued that Islamic spirituality, as a result of Islamic ethics, impacts various factors that affect the organisation's performance (Putranto & Trihudiyatmanto, 2021) and employee performance (Nasution et al., 2021) in the financial sectors.

Given the paucity of research in this area, this work delves into the influence of Islamic spirituality on organisational commitment and job satisfaction as well as analyses the impact of Islamic work ethics as a facilitator of religious spirituality on this relationship in the case of Indonesia. Concisely, the positive influence of Islamic spirituality on job satisfaction and organisational commitment through work ethics is a vital component in exploring the phenomena. Furthermore, the cases of corporate scandals and collapses provided evidence that moral misconduct among employees have contributed to the financial disaster of many companies. This renders rationale for a possible relationship between work ethics and organisational commitment (Manan et al., 2013), organisational innovations as being impacted by organisational culture (Uzkurt et al., 2013), Islamic work ethics and adaptive performance with the mediating role of innovative work behaviour and moderating role of ethical leadership among employees (Javed et al., 2017). Hence, this study investigates Islamic spirituality, work ethics and work attitudes within one framework that features both mediating and moderating impacting the organisational commitment whereby affecting the performance of companies.

The findings of this study redound the benefit of business information considering that spirituality plays an important role in shaping work ethics and work attitudes, implying the demand for companies to accommodate spiritual needs. Lastly, this paper will help uncover critical areas in spirituality from an Islamic perspective, thereby gaining a new understanding of workplace spirituality through empirical verification and substantiation.

Given that Indonesia is a Muslim country with a secular constitution and institutional frame, selecting Indonesian employees is significant. Albeit, religion is embedded in the behavioural system of individuals, while the political articulation of Islam is lacking. The civil society dynamics have been an important source of religious development in the country (Hefner, 2000). Therefore, it is expected that work ethics derived from Islamic ethos should be high among Indonesian employees instead of a sample of employees drawn from countries where Islam is relegated to symbolic meanings or politicised.

Among further contributions, this study makes a distinction about the observed gap in the literature. In this study, work ethics is considered as a model, respectively mediating and moderating variables in job satisfaction and organisational commitment. While using the same variable in two functions might be regarded as problematic, we endeavour to go beyond the existing studies of capture the dynamics and Islamic spirituality on job satisfaction and commitment. While it is the same variable, its functioning as meditating and moderating takes place independently. The main thrust here is that Islamic spirituality is all encompassing by having implications on every aspect of life, including job satisfaction and organisational commitment. Through the debate on spirituality and the subsection referring to hypotheses H4 (Job satisfaction developed through Islamic spirituality positively affects organisational commitment) and H6 (Work ethics developed through Islamic spirituality moderates the relationship between job satisfaction and organisational commitment), such impacts of Islamic spirituality have been explained. However, the literature is not clear whether job satisfaction affects organisational commitment or organisational commitment affects job satisfaction. This study shows (in Table 9) that job satisfaction positively affects organisational commitment. This should be considered as an initial attempt to fill the observed gap in the literature, which, of course, requires a more in-depth treatment in a single study. We believe that an experimental study will be best to provide solid empirical evidence, as it is the primary way to test/decide a causal relationship. Thus, in this study, we wanted to demonstrate the various impact areas of Islamic spirituality in the workplace, including job satisfaction and organisational commitment.

Furthermore, in an attempt to go beyond the existing formulations in the literature whereby to contribute to the literature, we included H5 that ‘Work ethics mediates the relationship between Islamic spirituality and work attitudes. It may be argued that it is inappropriate to reuse or combine job satisfaction and organisational commitment scale for work attitudes. In an attempt to contribute to the literature, in this paper, we argue that the two individual measures of work commitment focus on slightly different aspects of work commitment. We, therefore, combine the two indices latent variables into one. Wood et al.’s (2019) use of three-level indices of ‘positive workplaces attitudes’ substantiates our position. Although they have included a single overall index in all their tables, they did not particularly hypothesise it; instead, they only hypothesise each component (such as job satisfaction) separately. In line with their studies, we consider H5 will be a contribution to the existing literature by presenting a novel approach. However, this study acted more explicitly and therefore treated it with a hypothesis. Thus, for an exploratory purpose, we have also tested a single work attitudes index as represented by two dimensions: job satisfaction and organisational commitment, which we believe can be a contribution to the field.

Lastly, this study has achieved a large sample (845) size in generating data through a questionnaire survey in Indonesia, which has increased the strength of the conclusions drawn from the analyses.

Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

The term ‘spirituality’ is defined as the innate capacity of the human brain to form meaning, values and beliefs (McCormick, 1994; Howard, 2002; King & Crowther, 2004; Klerk, 2005; Zohar & Marshal, 2005; Altman, 2010). Additionally, it is characterised by having physical, affective, cognitive, interpersonal and mystical properties (Kinjerski & Skrypnek, 2004). Such qualities are expected to affect one’s work ethics and attitude, and hence in the workplace.

‘Spirituality in the workplace’ describes an organisational culture that encourages trust, cohesiveness, support, acceptance, innovation and fairness through work processes. It differentiates the meaning of individual and organisational spirituality in the workplace (Kinjerski & Skrypnek, 2004; Neck & Milliman, 1994). Both are believed to provide positive results for employees and employers (Khrisnakumar & Neck, 2002), such as shaping competitive advantages and excellent performances. More specifically, Giacalone and Jurkiewicz (2003) agree that spiritual-based organisational culture is the most productive. Paying attention to spiritual needs helps pave organisations perform better (Konz & Ryan, 1999; Polly et al., 2005), and increasing spirituality in the workplace leads to creativity, satisfaction, less fear and less abuse (White, 2001).

Spirituality nourishes the essence of the work attitudes in the workplace through internal preferences (Ashmos & Duchon, 2000; Duchon & Plowman, 2005). As employees spend most of their time at work (Adawiyah & Pramuka, 2017; Hill et al., 2000), it is assumed that religious believes and spirituality is inseparable in the workplace. This includes prayers and worships as part of a personal quest for sacred ((Hill et al., 2000) to increase the employees’ effectiveness in the workplace (Kazmi, 2004; Marques et al., 2005).

The main question that drives this research is the employment of spirituality in the workplace, shaping work attitude leading to job satisfaction. Within Islamic normativeness, emphasise on the spirituality of workers is conceptualised through homoIslamicus (Islamic personality), who automatically factors Islamic moral precepts into decision making (Abdul Hamid, 2015; Asutay, 2007, 2012).

Islamic Spirituality and Work Attitudes, Job Satisfaction and Organisational Commitment

Islamic ethical system relates to the relationship of individuals with God and the universe and their relationship with other individuals and creations. This cognitive system, through its ethical norms and form determines all the relationships, including the economic and political system, by giving meaning and solutions for various organisational problems (Adawiyah & Pramuka, 2017; Al-Attas, 2001). Such a relationship with God is an essential part of spirituality shaping human behaviour (Nasr, 1985a, 2008; Ragab, 1993). As an articulation of such level, comprehensive characteristics and intrinsic motivation embedded in Islamic spirituality, it, for example, encourages employees to demonstrate generous behaviour in organisations (Kamil et al., 2011a).

The concept of spirituality in Islam involves individual and organisational aspects through the work as a form of worship (ibadah), as in Islam, work is considered an essential element of success in life (Hashim, 2010; Ahmed et al., 2019) and working is perceived as part of religious and spiritual journey for individuals. Incorporating such spirituality comprises individual religiosity and organisational system. Therefore, among others, Adawiyah and Pramuka (2017) incorporate religiosity in the form of individual and organisational spirituality. This is supported by Lips-Wiersma (2002), who argues that individuals connect their spirituality with the meaning of personal life and organisational context. It is important to note that organisational spirituality influences work attitudes, whereas individual spirituality supports the interaction between organisational spirituality and work attitudes (Kolodinsky et al., 2008; Milliman et al., 2003; Pawar, 2009).

According to Mohsen (2007), Islamic spirituality is an embedded concept in taqwa or piety in the form of God consciousness. Because Islam considers work as an important element of human success in life, it does not only encourage individuals to work but also motivates them to seek excellence or ihsan in what they do (Hashim, 2010), as the concept of rububiyah (developing towards perfection as creation requires) and tazkiyah (purified growth) essentialises seeking for excellence or ihsan (Asutay, 2007, 2012, 2013). This universal aspect manifests the teachings of Prophet Muhammad and his companions. Thus, Islamic spirituality has a comprehensive intrinsic motivational feature, which tends to move Muslim workers toward exemplary behaviour within the organisation (Abuznaid, 2006; Bhatti et al., 2016).

At the ground level, organisational spirituality can be viewed as the union of ideals and spiritual values of a person (Kolodinsky et al., 2008). The intrinsic view found that spirituality is a concept derived from the individual level (Howard, 2002; Krishnakumar & Neck, 2002a, 2002b; Neal, 1997). However, its application at the individual level within an organisation leads to the prevailing spirituality in an organisation, as an organisation is a collection of individuals (Turner, 1999). Thus, people with a higher level of spirituality have better, happier and more productive life at work leading to job satisfaction, which contributes to organisational performance (Tischler et al., 2002).

The sense of belonging is also important, as Islam encourages cooperation among employees. The feelings of being connected to a community meeting the needs of human interaction, which then encourages job satisfaction (Pawar, 2009), which is also consistent with Islamic teaching of muamalat or human-to-human transactions. Commitment to Islam means binding on the principle and philosophy, which is articulated as a social contract with humans who are bound and believe in them (Motahari, 2010). Consequently, individuals accept the goals and values of an organisation and provide much effort on behalf of it (Mayer and Schoorman, 1992; Steers, 1997).

Spirituality in the workplace matches personal beliefs and values and that of an organisation (Mitroff & Denton, 1999). When individuals are more productive, more satisfied with their work, they tend to sustain their membership and choose organisations in which their spirituality fits their spirituality (Konz & Ryan, 1999; Luthans, 2006; Mowday et al., 1979; Rego et al., 2007). In addition, their commitment is stronger when spirituality is present in the workplace (McCormick, 1994; Rego & Cunha, 2007). They may leave when personal and organisational goals are no longer aligned (Lips-Wiersma, 2002). Islam urges all Muslims to do their best at work, which requires full commitment (Hashim, 2010).

Spirituality in the workplace, hence, can improve happiness, serenity and work attitudes, such as job satisfaction and organisational commitment (Delbecq, 1999; Fry, 2003; Hashim, 2010; Krishnakumar & Neck, 2002a, 2002b; Milliman et al., 2003; Reave, 2005). Similarly, the existing body of knowledge supports the belief that spirituality is expected to stimulate employees' honesty, creativity, commitment and personal fulfilment within an organisation (Giacalone & Jurkiewicz, 2003; Gull & Doh, 2004; Klerk, 2005).

As a result, the following hypotheses are developed:

H1

Driven by Islamic ethics, Islamic spirituality positively affects work attitudes

H1a

Driven by Islamic ethics, Islamic spirituality positively affects job satisfaction

H1b

Driven by Islamic ethics, Islamic spirituality positively affects organisational commitment.

Islamic Spirituality and Work Ethics

The concept of work ethics, from the Islamic perspective, is originated from the Qur’an as well as the words and practices of the Prophet Muhammad. He proclaimed that ‘the hard work caused the sins to be demolished’ and ‘no one eats better food than he eats from his work’ (Sahih al-Bukhari, 2072, Book 34, Hadith 25). On the other hand, Islamic normativeness defines human salvation through spiritual attainment, namely taqwa, by becoming insan-i kamil or excellence in human quality. Thus, Islamic ethics and spirituality are explicitly attached to each other. Furthermore, the work ethics of Islam see the dedication to work as a virtue and allows people to become independent, and a source of self-esteem, satisfaction and fulfilment as success and progress in work depends on hard work and commitment to work (Ali & Al-Kazemi, 2007; McGhee & Grant, 2008). Therefore, an adequate effort must be spent in working. Consequently, it is argued that letting and encouraging spirituality in the workplace leads to better ethical behaviour at an individual level and an enhanced ethical or cultural climate at the organisational level (Md. Anwar et al., 2020).

One of the most important justifications for introducing spirituality to an organisation is through essentialising ethics (Polly et al., 2005), for example, by developing ethical behaviour (Maclagan, 1991) and a more cohesive vision and purpose (Kahnweiler & Otte, 1997). As a regulative ideal, spirituality produces embedded networks of certain moral value, which provides standard and ethical understandings to determine moral choices within day-to-day work practices (McGhee & Grant, 2008). Islamic spirituality, by definition, is consistent with the daily application of religious values. It correlates to perceptions, basis and determinants of ethical behaviour in business (Giacalone & Jurkiewicz, 2003; Gull & Doh, 2004; Klerk, 2005), as it is argued that spiritual people are ethical people, and such people are beneficial to the organisation (McGhee and Grant, 2008).

In harmony with Islamic values and principles, actions and behaviours require believers to do all activities to attain Allah’s love, forgiveness and help (Bhatti, 2015). The remembrance of Allah, praying five times a day, fasting and charity is expected to strengthen spirituality. As a result, spiritually powerful believers are expected to exhibit honest, faithful, hardworking and principled behaviour (Bhatti, 2015).

Accepting spirituality as the central aspect of human existence suggests ethical correctness, largely distinct from a pecuniary motive (Polly et al., 2005). However, the personal ethical framework affects individual ethical behaviour, so a more appropriate unit of analysis when investigating ethics may be individual (Klerk, 2005). The value of Islamic religiosity is an individual approach based on an institutionalised system, which encourages every Muslim employee to behave ethically. At the individual level, research has suggested a positive causal relationship between value orientation based on spirituality, ethics and work performance (Giacalone & Jurkiewicz, 2010). Thus, it is hypothesised that:

H2

Islamic spirituality positively affects work ethics.

Work Ethics and Attitudes

Attitude is a mental state, which is learned and organised through experience, producing a specific influence on an individual’s response to another object or related situation (Ivancevich et al., 2005). In the current study, we focus on job satisfaction and organisational commitment vis-à-vis work attitude as they are regarded critically important for organisational functioning (Harrison et al., 2006), and these are examined to investigate their reciprocity and their relation to Islamic spirituality and work ethics.

Work attitudes are described in several dimensions. In this study, two dimensions, namely job satisfaction and organisational commitment, are examined to investigate their reciprocality and relation to Islamic spirituality and work ethics.

Explicit standards are important segments of organisational commitment in creating positive attitudes among employees to distinguish between ethical and unethical behaviour (Valentine & Barnett, 2003). Organisational values, generally, include forms that reflect individual attitudes (Cherrington, 1980), those attributed to the organisation, embedded in structures and processes, and those that represent collective concerns and beliefs about its effective functioning (Bourne & Jenkins, 2013). Within this setting, the economic, moral and social dimensions of work ethics provide a sense of worthiness and strengthen organisational commitment and continuity since success and progress on the job depends on hard work and commitment to the job (Ali & Al-Owaihan, 2008). It enables a person to be independent and is a source of self-respect, satisfaction and fulfilment. Thus, work ethics affects work attitudes as demonstrated by the strong association to job satisfaction and positive relationship to organisational commitment. Those who strongly support work ethics, according to the Islamic perspective, are more satisfied with their jobs (Yousef, 2001) and more committed to their organisation, as a commitment to the job in Islam is considered as a virtue (Yousef, 2000). Thus, it is hypothesised that:

H3

Work ethics developed through Islamic spirituality positively affects work attitude

H3a

Work ethics developed through Islam spirituality positively affects job satisfaction

H3b

Work ethics developed through Islam spirituality positively affects organisational commitment.

Job Satisfaction and Organisational Commitment

Job satisfaction is most a positive and effective response toward a job that comes out as a result of meaningful work, a sense of community and the value of the organisation (Hassan et al., 2016). As an attitude, job satisfaction is different from commitment, which reflects a response to work or a certain aspect of work and measure to which a person likes or dislikes his job (Spector, 1985), whereas commitment is more global, reflecting general affective responses to the organisation as a whole and individual’s psychological identification and attachment to the organisation (Jaramillo et al., 2006). Hence, job satisfaction emphasises a specific task environment, while commitment emphasises attachment to the organisation, including its purpose and value (Mowday et al., 1979). However, there is a significant and positive relationship between job satisfaction and organisational commitment. When individuals receive a sense of satisfaction from their jobs, they show a favourable overall attitude toward their work and respond with an increased commitment to the organisation. For example, Tekingündüz et al. (2017) revealed that organisational commitment in the form of trust, promotion, managers, the structure of work, etc., have a meaningful effect on job satisfaction.

Consequently, the following hypothesis is developed:

H4

Job satisfaction developed through Islamic spirituality positively affects organisational commitment.

Work Ethics as a Mediator of Islamic Spirituality and Work Attitudes

Islamic spirituality is the foundation that drives an attitude to work and attitudes within the workplace, leading to organisational commitment as observed through their workplace ethics (Wan Husin & Zul Kernain, 2020). Gatling et al. (2016) investigate the extent to which workplace spirituality (WPS) is related to employees’ organisational commitment (OC) through the lens of self-determination theory. Their findings suggest WPS are positively related to OC. Lumpkin and Achen (2018) provide a theoretical perspective where self-determination theory synergises ethics and work attitudes.

Islamic work ethics as a way of introducing spirituality (Nasr, 2008) implies that Islamic spirituality can be articulated into work attitudes when there is a set of ethical norms that can guide individuals to behave as required in line with Islamic spirituality and believed by the individuals (Kahnweiler & Otte, 1997; Karakas, 2010). As Islamic spirituality influences work attitudes, work ethics influences work attitudes, and the manifestation of work ethics according to the Islamic perspective implies the role of Islamic spirituality (Wan Husin & Zul Kernain, 2020). In this process, there must be an interaction model among Islamic spirituality, work ethics and two aspects of work attitudes: job satisfaction and organisational commitment.

Islamic spirituality is believed to be a crucial dimension of one’s personality, and therefore, the organisation that encourages spirituality will encourage people to bring themselves into the work (Krishnakumar & Neck, 2002a, 2002b; Maham et al., 2020; Neck & Milliman, 1994). The self-actualisation process of Islam is purely based on a balanced social development (maslaha ammah) through the correction of one-self (tazkiyatu nafs) (Al Haq and Wahab, 2021). Consequently, those with high spirituality and work ethics supported by organisations and work ethics will withstand the work challenges and have a good work attitude (Klerk, 2005). The relationship of Islamic spirituality, work ethics and work attitude results in synthesis. Thus, it is hypothesised that:

H5

Work ethics mediates the relationship between Islamic spirituality and work attitudes;

H5a

Work ethics mediates the relationship between Islamic spirituality and job satisfaction;

H5b

Work ethics mediates the relationship between Islamic spirituality and organisational commitment.

Work Ethics as a Moderator of Job Satisfaction and Organisational Commitment

Several studies have examined the relationship between ethics, job satisfaction and organisational commitment, which demonstrated a strong influence between work ethics on job satisfaction (Cherington, 1980; Ali, 1988; Saks et al., 1996) and organisational commitment (Kidron, 1978; Putti et al., 1989; Saks et al., 1996). However, some find job satisfaction affecting organisational commitment (Porter & Streers, 1973) or the way round (Vandenberg & Lance, 1992), and others finds no influence between the two (Curry et al., 1986). Investigated in previous research within an Islamic context, work ethics directly affects both job satisfaction and organisational commitment, and it moderates the relationship between those constructs (Gheitani et al., 2019; Yousef, 2001). The results from the existing literature indicate that work ethics and job satisfaction interact in their effects on organisational commitment. It also demonstrates that improving organisational commitment requires enhancing both job satisfaction and support of the work ethics (Yousef, 2001). Thus, it is hypothesised that

H6

Work ethics developed through Islamic spirituality moderates the relationship between job satisfaction and organisational commitment.

Methodology

Data Assembly Through Questionnaire Survey

The primary data for this study were collected from the first-hand experience through a Likert-scale-based online survey addressed to the employees in Indonesia through convenience sampling technique, which is a procedure to obtain samples based on their accessibility to the researcher. In administrating the data collection, questionnaires were sent through an online survey to 1000 individuals and 845 were fully completed resulting 84.5% response rate. The remaining 155 questionnaires were partially completed, and therefore, they were not included in this study.

The questionnaires were completed through an online survey in the local language, namely Bahasa Indonesia, which was set to only one response per IP address to avoid redundancy. It was translated from and back translated to English of the same earlier translated document to assess the credibility and found that both versions were similar. An avoidance of ‘neutral response’ was applied since Indonesian people are assertive and moderate. Negative (reverse-scored) words were also omitted as they reduce validity (Baumgartner & Steenkamp, 2001) and lead to systematic error to a scale (Swain et al., 2008).

The questionnaire used in this study consisted of fifty questions in four constructs: Islamic spirituality (twenty items), work ethics (seventeen items), job satisfaction (four items) and organisational commitment (nine items). The questionnaire statements can be seen from Appendix Table 11 and Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4 in the empirical section.

Questionnaire Construct and Variable Measurement

This study utilises Adawiyah and Pramuka’s (2017) Islamic spirituality, which is segregated into 14 items that symbolise individual level spirituality, which in essence adapted Allport and Ross (1967), Hawa (2006) and Kamil et al. (2011b), while 6 items corresponding to an individual’s affiliation to institutional values were adapted from Milliman et al. (2003).

Work ethics is defined as values and moral principles in the workplace, for which Ali (1992) and Yousef’s (2000, 2001) constructs were adopted consisting of 17 items. It was used to test Islamic work ethics in Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Kuwait. Job satisfaction is an individual feeling of work assessed by three items from satisfaction with advancement and opportunities from hygiene theory (Herzberg et al., 1959) and one item from satisfaction with the nature of work (Nathan et al., 1991). Organisational commitment is defined as a strong desire to remain a member and strive for an organisation's interests, which is assessed by Mowday et al.’s (1979) organisation commitment scale.

It should be noted that the relevant literature evidence that common method variance prevails as the dominant approach in the behavioural sciences. However, in this study, all variables are measured by employees’ self-report, which, accordingly, may constitute a concern. In reflecting on why only single source self-report measures are used in this study, it is theoretically we can argue all processes we examined in this paper are ‘intrapersonal’, as they occur within the individual employees, not between them. Accordingly, for example, social cognitive theory (see: Bandura, 1991) or conversation of resources theory (see: Hagger, 2015) explains these intra-personal processes. The social cognitive theory suggests that personal influences - such as trait, behaviour, cognition, affect and contextual influences such as environmental influences - serve as interacting determinants of each other. On the other hand, according to the conversation of resources theory, the fit of personal, social and environmental resources with external demands determines the direction of coping capabilities in handling challenges. In such a process, when there is a mismatch between situational demands and personal resources, stress arises and performance diminishes, whereby stress or satisfaction at work emerges. Thus, in both cases, there is an important influence on positive workplace attitudes. In this study, hence, Islamic spirituality is considered positively contributing to the development of workplace attitudes.

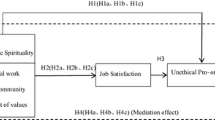

Empirical Model

Figure 1 brings together all the developed hypotheses to illustrate the aims of this research through Structured Equation Modelling (SEM). As can be seen in the following section, each of the following relationships has been proven by this research, except the possibility of ethics to mediate the relationship between Islamic spirituality and work attitudes. Still, the available body of knowledge states that Islamic spirituality, work ethics and work attitudes impact each other, including its dimension, if any, as ethics playing a mediator role is possible.

Validity, Reliability, Normality and Outliers Footnote 1

In ensuring the validity of the assembled data, it is examined through factor loading, resulting in 39 valid indicators out of 50 with factor loading ≥ 0.40. This implies that as many eleven indicators should be excluded to get all constructs extracted perfectly, i.e. eight of Islamic spirituality (IS1, IS5, IS16, IS17, IS18, IS19 and IS20) and three of work ethics (WE11, WE12 and WE17).

As for reliability, it is examined using AMOS 6.0. The results indicated that 39 indicators with reliability value > 0.70 should be included in this study, as variables with value > 0.70 are considered reliable. The reliability test's overall results are as follows: Islamic spirituality scored 0.904, work ethics 0.908, job satisfaction 0.877 and organisational commitment 0.914. Since construct reliability scores are all higher than 0.7, they are all considered reliable.

As part of the empirical assumptions, outlier evaluation is tested to 100, which is the number of observations that can help obtain Mahalanobis distance criteria of x2 significance at p < 0.001 (100, 0.001), resulting in 52.61966. Any number exceeding the value is considered an outlier. The results verify that among 845 samples, as many as 100 have been found with Mahalanobis distance of more than 52.61966. Thus, those with 100 should be taken out to avoid bias on the results since this study aims to determine a predicted model or generalisation, which left 750 samples to be used for analysis.

Lastly, the normality test was conducted, which compares C.r. skewness and kurtosis, which shows that C.r. skewness < 2 as normal for univariate while C.r. kurtosis at 42.814 > 21 for multivariate is highly non-normal. However, normality assumption can be ignored for research employing a large sample, such as larger than 200 (Hair et al., 2010).

Empirical Findings

Descriptive Results

The demographic characteristics of the respondents are detailed in Appendix Table 11, which shows that 56.3% of the respondents are female, and the 21–30 age group represents 81.1% of the respondents. It can also be seen that 76.5% of the respondents have a bachelor’s degree, while about 20% works in the education sector and 12.3% works in the government sector. Table 11 in Appendix also shows that 55.5% of the respondents’ job level is staff, while 16.5% is a field worker and 15.3% is coordinator/supervisor.

Table 1 shows that 92.43% of the respondents experienced and have a positive response to Islamic spirituality in the workplace. The highest value (84.4) strongly agrees with the influence of religious practice, whereas the lowest (0.2) lies in disagree for the correlation of feeling happy and helping others.

Regarding work ethics, Table 2 depicts that 93.30% of respondents are considered to have and practise a set of ethics in their workplace. The highest extreme value (62.5) appears in agree for the ability to control nature, whereas the lowest (0.2) lies in both disagree categories for four indicators of meaning in life, the benefit of good work, responsibility and the best ability.

As shown in Table 3, most of the respondents (81%) feel satisfied with their job in general. The highest extreme value (60.2) appears in agree for respondents’ satisfaction with the nature of work, whereas the lowest (1.2) lies in strongly disagree for having an opportunity of advancement in job.

Regarding organisational commitment, as depicted in Table 4, the majority of respondents (77.66%) committed to their organisation, where the highest value (64.3) appears in agree for respondents’ effort to help their organisation, whereas the lowest (0.6) lies in strongly disagree for doing beyond expected effort.

Analytical Results

Table 5 shows the fitness results of the undertaken model. Some criteria are not fulfilled, such as Chi-square is not assumed low, significance probability (p) is far below 0.05 and CMIN/DF > 2.00. GFI and AGFI almost reach 0.90, hence considered as marginal fit. TLI and CFI are a good fit at > 0.90. RMSEA is < 0.08, which is good. Thus, it is not necessary to modify the model. The overall model in this study is acceptable.

Table 6 displays the findings from path analysis for the direct, indirect and total effects.

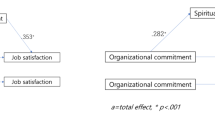

An analysis of direct and indirect effects needs to be observed to obtain a more detailed interpretation of the hypotheses. This analysis is also used to determine the strength of the constructs’ influence, both directly and indirectly. As can be seen in the first panel in Table 6, all direct effects are positive, and it occurred between Islamic spirituality to work ethic, job satisfaction and organisational commitment; work ethics to job satisfaction and organisational commitment; and job satisfaction to organisational commitment. The highest score is between work ethics and Islamic spirituality. The second panel in Table 6 shows the coefficient of the indirect effect of Islamic spirituality on job satisfaction and organisational commitment and work ethics to organisational commitment. The coefficient of total impact in the bottom panel of Table 6 shows that Islamic spirituality has a higher indirect impact on job satisfaction and organisational commitment than the direct effect. Figure 2 places the results for the established relationships.

Testing Mediation Effect

Two models were tested to examine the mediation role of work ethics: (i) Islamic spirituality to job satisfaction and organisational commitment without mediation and (ii) with mediation. The first panel in Table 7 shows a significant influence of Islamic spirituality on job satisfaction and organisational commitment before mediated through work ethics. It also shows the non-significant influence of the same relations after mediated through work ethic. Hence, the findings evidence an influence of mediation. Three paths have significant influence indicated by p < 0.05 and C.r. > t table ± 1.96. The path coefficient analysis is also used to examine the indirect effect.

Sobel test was also employed, as shown in Table 8, which indicates work ethics as a mediator for the influence of Islamic spirituality on job satisfaction and organisational commitment.

Testing the Moderation Effect

To examine the moderation role of work ethics, two models were tested: constraint and unconstraint, both with high and low work ethics. Table 9 shows that job satisfaction significantly affects organisational commitment at p < 0.05 regardless of work ethic.

The goodness of fit of the two models was also estimated. As shown in Table 10, the difference is considered small; therefore, work ethics do not moderate the influence of job satisfaction on organisational commitment.

Hypotheses Testing

Based on the results generated in the analyses above, the hypotheses set in “Methodology” section are tested in this section.

H1a

Islamic spirituality affects the job satisfaction.

As shown in the first panel of Table 7, Islamic spirituality positively affects job satisfaction, indicated by C.r. 10.141 significant at p < 0.05. Thus, the hypothesis is supported. Unlike the previous studies, which prove that spirituality has no effect on job satisfaction (Pawar, 2009) or even negatively affects (Buana, 2013), this study incorporates the religiosity aspect within Islamic conceptualisation, resulting in a positive outcome.

In line with Islamic spirituality, that work is considered worship (Adawiyah & Pramuka, 2017), a spiritual person works sincerely to seek Allah’s blessings. Therefore, intention to work is associated with worship, which emphasises understanding intention over the result. It then encourages individuals to optimise their effort, which turns to satisfaction as Freeman (1978) says that job satisfaction enhances the utility earned from the effort. Those correlations put work intention as the way of fulfilling spiritual needs where it is the highest in Maslow’s pyramid.

For Islamically spiritual people, the worship needs are also achieved through working, and hence, job satisfaction will automatically follow. This has been the general attitude in Indonesia. The intention is often perceived to justify an action, including work, as evidenced by the majority of respondents who agree that the value of the work is derived from the accompanying intention, not from the results.

H1b

Islamic spirituality affects organisational commitment.

Based on the result of hypotheses testing as shown in the first panel of Table 7, Islamic spirituality positively affects organisational commitment, indicated by C.r. 10.221 significant at p < 0.05. Thus, the hypothesis is supported. Previous studies evidence that spirituality does not affect organisational commitment (Pawar, 2009) and negatively affects (Buana, 2013), while this study establishes that the direction is positive by incorporating the religiosity aspect within Islamic conceptualisation.

Muslims are encouraged to do their best in work, which requires full commitment (Hashim, 2010). The influence of Islamic spirituality on organisational commitment can be attributed to similarity as employees remain their membership if organisational spirituality fits their spirituality (Konz & Ryan, 1999; Luthans, 2006; Mowday et al., 1979; Rego et al., 2007). Therefore, Islam suggests Muslims find a job that aligns with Islamic values, so they have a strong commitment to their work.

Among 20 indicators of Islamic spirituality, the last 6 demonstrate alignment with organisational values as one of the organisational spirituality dimensions do not pass the validity test. Although the results state that Islamic spirituality influences organisational commitment, the underlying factor is religiosity, equating with spirituality at an individual level rather than the alignment. On the other hand, Buana (2013) proves that organisational spirituality can be a means of commitment building. This evidence implies that in terms of Islamic conceptualisation, the individual level of spirituality plays much more than the organisational level.

H1

Islamic spirituality affects work attitudes.

Based on the result in the first panel of Table 7, it can be concluded that Islamic spirituality affects work attitudes, which in this study are represented by two dimensions: job satisfaction and organisational commitment. It is seen from the value of C.r. significant at p < 0.05 for both dimensions. Thus, the hypothesis is fully supported.

H2

Islamic spirituality affects work ethics.

Based on the result of hypotheses testing as shown in the second panel of Table 7, Islamic spirituality positively affects work ethics, indicated by C.r. 13.980 significant at p < 0.05. Thus, the hypothesis is supported. There is no prior study that has investigated the relationship between Islamic spirituality and work ethics. However, the possibility of the influence is viewed from the definition of ethics as a moral and values standard rooted in spirituality and religiosity.

Spirituality in the workplace can be justified through ethics (Polly et al., 2005), meaning that ethics is a reflection of spirituality embodied in a set of rules or norms. The rules may be collectively applied by an organisation, such as in the form of ethical behaviour (Maclagan, 1991), vision and purpose (Kahnweiler & Otte, 1997), or individually, such as code of conduct based on religious beliefs as to attain the blessings of Allah (Bhatti, 2015). The content of Islamic spirituality is derived from Islamic religiosity, containing norms that govern humankind and the standards applied in everyday life and the workplace. Islamic spirituality in the workplace aligns with day-to-day religious values, which also become the fundamental of ethical behaviour. For employees with higher Islamic spirituality tend to exhibit good work ethics, violating the ethics equals violating religious values.

This religious paradox is currently under the spotlight in Indonesia. The symbols of Islam in the workplace are contrasted to the trend of corrupt behaviour. However, it can be argued that employees who perform such unethical acts are not spiritual people but those who have instrumentalised and relegated Islam to symbolic presence. Indeed, defining spiritual people as ethical people (McGhee and Grant, 2008) distinguishes spirituality from religiosity. Islamic spirituality is expected not manifested symbolically but internalised in work ethics.

H3a

Work ethics affects job satisfaction.

Based on the result of hypotheses testing as shown in the second panel of Table 7, work ethics positively affect job satisfaction, as indicated by C.r. 8.181 significant at p < 0.05, which verifies the hypothesis. As Cherington (1980) and Ali’s (1987) work shows, ethics and job satisfaction are closely related. Standards or ethics is the determinant of attitudes and behaviours, which guides individuals to behave and enables them to be independent. The independence then becomes a source of self-respect, satisfaction and fulfilment (Valentine and Barnet, 2003; Ali & Al-Owaihan, 2008). Therefore, as also supported by Yousef (2001) from the Islamic point of view, those who strongly support work ethics will be more satisfied with their work.

H3a

Work ethics affects organisational commitment.

Based on the result in the second panel of Table 7, work ethics positively affect job satisfaction, as indicated by C.r. 8.570 significant at p < 0.05, which supports the hypothesis. As studied by Putti et al. (1989), ethics and organisational commitment are also closely related. In the context of the work environment, the analogy of compliance to ethics can be likened with compliance to the organisation. Therefore, as also supported by Yousef (2000) from the Islamic point of view, those who strongly support work ethics will be more committed to their organisation since commitment to work in Islam is a virtue.

H3

Work ethics affects work attitudes.

The results in the first panel of Table 7 depicts that work ethics affects work attitudes, which in this study are represented by two dimensions: job satisfaction and organisational commitment. This is verified by the value of C.r. being significant at p < 0.05 for both dimensions, upholding the hypothesis.

H4

Job satisfaction affects organisational commitment.

As shown in Table 9, job satisfaction positively affects organisational commitment, as evidenced by C.r. 15.677 being significant at p < 0.05, supporting the hypothesis. Based on previous studies, there are differences in findings on the influence of job satisfaction on organisational commitment. According to Porter and Steers (1973), job satisfaction affects organisational commitment, while according to Vandenberg and Lance (1992), organisational commitment affects job satisfaction. Moreover, Curry et al. (1986) argue that there is no influence between job satisfaction and organisational commitment. If viewed from the definition of job satisfaction and factors that motivate employees to survive in a company as a form of commitment, the hypothesis that job satisfaction affects organisational commitment is more likely supported.

H5a

Work ethics mediates the relationship between Islamic spirituality and job satisfaction.

As depicted in the second panel of Table 7, Islamic spirituality positively affects job satisfaction with work ethics as the mediating variable. It is indicated by C.r. 13.980 being significant at p < 0.05 for Islamic spirituality on work ethics and C.r. 8.181 being significant at p < 0.05 for work ethics on job satisfaction. The indirect effect of Islamic spirituality on job satisfaction is 0.278, whereas the direct impact is 0.117. Hence, the influence of Islamic spirituality on job satisfaction is mediated by work ethics, which supports the hypothesis.

H5b

Work ethics mediates the relationship between Islamic spirituality and organisational commitment.

The results in the second panel of Table 7 show that Islamic spirituality positively affects organisational commitment with work ethics as the mediating variable, as evidenced by C.r. 13.980 being significant at p < 0.05 for Islamic spirituality on work ethics and C.r. 8.570 being significant at p < 0.05 for work ethics on organisational commitment. The indirect effect of Islamic spirituality on organisational commitment is 0.374, whereas the direct impact is 0.017. Hence, the influence of Islamic spirituality on organisational commitment is mediated by work ethics, which verified the hypothesis.

H5

Work ethics mediates the relationship between Islamic spirituality and work attitudes.

At the beginning of the hypotheses explanation, it is mentioned that Islamic spirituality positively affects job satisfaction and organisational commitment. Based on the result in Table 8, both paths of Islamic spirituality to job satisfaction and organisational behaviour are significant. The initially significant influence at p < 0.05 becomes non-significant after mediated by work ethics. Therefore, total mediation is considered as taken place.

Based on the rules of mediation, according to Baron and Kenny (1986), mediation requires the influence of independent variable on mediation variables (a); the impact of mediation variables on the dependent variable (b); and the effect of independent variables on the dependent variable (c). If only one of the three relationships is not supported, mediation will not occur. According to Zhao et al. (2010), if all three paths have the same sign (direction of relationship), the mediation is considered complementary. In this case, the influence of Islamic spirituality on work attitudes is mediated by work ethics. Thus, referring to the explanation, the hypothesis is fully supported and categorised as a complimentary mediation.

H6

Work ethics moderates the relationship between job satisfaction and organisational commitment.

As the estimates in Table 9 demonstrate, since the value of C.r. is always significant at p < 0.05 regardless of the existence of work ethics, work ethics does not moderate the relationship between job satisfaction and organisational commitment. Thus, the hypothesis is not supported. This can be explained that both job satisfaction and organisational commitment are the dimensions of one same variable, namely work attitudes. Also, according to the previous studies, the relationships between the two may vary, affecting each other or be no effect at all. These results contradict the previous research, which reveals that work ethics (in Islamic point of view) can moderate the influence of job satisfaction on organisational commitment. The reality in Indonesia shows that (i) although commitment is influenced by satisfaction, (ii) ethics affects satisfaction and commitment, (iii) the presence or absence of work ethics do not affect the relationship of job satisfaction on organisational commitment.

Conclusion, Implications and Limitations

This study examines the relationship between Islamic spirituality, work ethics, job satisfaction and organisational commitment. It also explores the mediation effect of work ethics on the influence of Islamic spirituality on job satisfaction and organisational commitment and the moderation effect of work ethics on the relationship of job satisfaction and organisational commitment. The findings demonstrate that Islamic spirituality positively influences job satisfaction and organisational commitment as two dimensions of work attitudes and that work ethics mediates that influence. Besides, there is evidence that job satisfaction positively influences organisational commitment, but work ethics does not moderate that influence.

It should be noted that the result that individuals in the organisations investigated are highly attached to Islamic spirituality and religiosity are consistent with previous research (such as Adawiyah & Pramuka, 2017; Ayoun et al., 2015; Hill et al., 2000; King & Crowther, 2004). The Islamic values brought to the workplace affirm the role of spirituality and religiosity, which views work as a form of worship and is an integral part of life (Ali & Al-Owaihan, 2008; Pramuka, 1998). Such positive ideas might result in several advantages, including job satisfaction and organisational commitment. The positive influence of Islamic spirituality on job satisfaction and organisational commitment has been significantly proven and supports previous findings (see: Mowday et al., 1979; McCormick, 1994; Konz & Ryan, 1999; Yousef, 2001; Luthans, 2006; Rego & Cunha, 2007; Rego et al., 2007). The findings suggest that those who strongly and consciously support Islamic spirituality are more satisfied with their work and more committed to their organisation, which will undoubtedly benefit both individuals and organisations, which is also verified by Lips-Wierma (2002).

Implications of the Study

The implications of the study are presented in the form of theoretical and practical implications, as follows:

Theoretical Implications

The results of this study provide several academic and theoretical implications, as it enhances the understanding of the role of Islamic spirituality and work ethics in influencing job satisfaction and organisational commitment, especially in the non-Western context.

The findings related to the role of work ethics, which mediates the influence of Islamic spirituality on job satisfaction and organisational commitment, can be considered as a significant contribution of this study. There is no previous research found which has examined the effect of such mediation among those variables. Therefore, this finding of this study can be considered novel. However, to affirm the evidence, there is a supporting logical frame, namely the role of ethics in articulating values into attitudes. In this case, Islamic spirituality is a spiritual value that is viewed from the perspective of Islam. The moral standards contained in Islam then become ethics practised in everyday life, which in the context of work is called work ethics. The form of daily activities is then called the work attitude, which among others, consists of job satisfaction and organisational commitment. This is supported by Maclagan (1991), Polly et al. (2005) and McGhee and Grant (2008).

The other findings related to the role of work ethics, which moderates the influence of job satisfaction and organisational commitment, are inconsistent with previous research conducted by Yousef (2001). In this study, work ethics is not proven to moderate the relationship between job spirituality and organisational commitment. It can be explained by the variety of forms of the influence between job satisfaction and organisational commitment (Curry et al., 1986; Porter & Steers, 1973; Vandenberg & Lance, 1992). The existence of the relationships is the underlying consideration to separate the overall model into two to avoid misinterpretation and confirm the moderation effect. On the other hand, as demonstrated by the model, work ethics influence both job satisfaction and organisational commitment, whereby it extends the available literature.

Practical Implications

Regarding practical and professional implications of this study, managers and employees considering doing business in Islamic markets, finding that Islamic spirituality influences job satisfaction and organisational commitment mediated by work ethics implies that to achieve higher levels of job satisfaction and organisational commitment, the organisation must provide support for the fulfilment of spiritual needs, in this case, Islamic spirituality for Muslim employees. In the business world, the company’s support for Islamic spirituality can be delivered through the application of work ethics. The above findings do not only benefit Muslim employees in Indonesia (where the study has been conducted), spiritual and religious doctrine has universal implications as Muslims and non-Muslims interact in the workplace of the modern world. Employees with higher Islamic spirituality will demonstrate good working behaviour (Mohsen, 2007; Kamil, 2011a; Bhatti, 2015) with no insult, humiliation, or offending fellow employees, regardless of colour, nationality, or religion (Bhatti et al., 2016). For non-Muslims, this research helps them increased awareness of Muslim co-workers' spiritual needs at work (Adawiyah & Pramuka, 2017).

Limitations and Challenges

As it is common in every research, this study certainly cannot be without limitations, consisting of two aspects. First, the lack of attention to the sensitivity of the questions in the questionnaire concerning Islamic spirituality. This allows social desirability involved in self-reports collected data. One of the preventive steps is to use an informant-based approach. Second, the normality of data that is classified as extremely non-normal considering the data used is the primary data with a large sample size. Based on the results of this research, suggestions that can be given are as follows.

The limitations of this study are pertinent, thus serving as avenues for future studies and research. On the first note, this study employed a cross-sectional research design. This reveals a short-term impact of Islamic spirituality influences job satisfaction and organisational commitment as two dimensions of work attitudes and that work ethics mediate that influence. Therefore, sustaining the extent of the Islamic spirituality’s effect on the performance might not be ascertained in the long run. A longitudinal design to determine the interaction term of this nature of the relationship can be utilised in further research. Additionally, a qualitative approach to complement the vast existence of quantitative research can enhance our understanding, as this will pave the way for the adoption of different tools for data collection and analysis that can improve the outcome of the study. Thus, direct interviews as support to investigate the conditions that cause non-normal data and get a deeper interpretation of the results of hypothesis testing will enhance our understanding of the dynamics of Islamic spirituality in the workplace.

The sample employed for this study was from Indonesian Muslim individuals in the workplace across all firms operating in Indonesia. Future research can direct research efforts on specific sectors of the economy such as education, banking, petroleum, health and hospitality, and other large and multinational organisations. More so, being that Indonesia is a multi-cultural, multi-ethnic and multi-religion country, future study could replicate the related research in other developing nations with different and diverse cultural, ethnic and religion settings. Thus, conducting similar research with different data sets to see the relationships and other control variables that might affect, such as nationality. Countries with large minority Muslim populations (India) or small minority Muslim populations (France and Germany) will be informative to compare.

Notes

Due to the length and space limitations, the test results for validity, reliability, normality and outliers could not be provided in the appendix. However, the results can be provided upon request.

References

Aburdene, P. (2005). Megatrends 2010: The Rise of Conscious Capitalism. Hampton Roads Publishing Company.

Ab, M., Wahab, A. Q., & Blackman, D. (2016). Measuring and validating Islamic work value constructs: An empirical exploration using Malaysian Samples. Journal of Business Ethics, 69, 4194–4204.

Adawiyah, W. R., & Pramuka, B. A. (2017). Scaling the notion of islamic spirituality in the workplace. Journal of Management Development, 36(7), 877–898.

Al-Haq, A. A., & Abd-Wahab, N. (2021). Towards Asnafs’ Islamic self-actualization process through sustainable balance scorecard (BSC) approach: a theoretical proposition. In S. H. Kassim, A. H. A. Othman, R. Haron, & I. G. I. Global (Eds.), Handbook of research on Islamic Social Finance and Economic recovery after a global health Crisis. IGI Global.

Al-Attas, S. M. (2001). Prolegomena: To the metaphysics of Islam: An exposition of the fundamental elements of the worldview of Islam. International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilization.

Al-Bukhari, (n/a). Sahih al-Bukhari, 2072, Book 34, Hadith 25, Vol. 3, Book 34, Hadith 286.

Aldulaimi, S. H. (2016). Fundamental islamic perspective of work ethics. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, 7(1), 59–76.

Ali, A. (1988). Scaling an islamic work ethic. The Journal of Social Psychology, 128(5), 575–583.

Ali, A., & Al-Kazemi, A. A. (2007). Islamic work ethic in Kuwait. Cross Cultural Management, 14(2), 93–104.

Ali, A., & Al-Owaihan, A. (2008). Islamic work ethic: A critical review. Cross Cultural Management, 15(1), 5–19.

Ali, A. J. (1992). The Islamic work ethic in Arabia. The Journal of Psychology, 126(5), 507–519.

Allport, G., & Ross, M. (1967). Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5(4), 432–443.

Altman, Y. (2010). In search of spiritual leadership. Human Resource Management International Digest, 18(6), 35–38.

Anwar, M. A., Gani, A. A. M. O., & Rahman, M. S. (2020). Effects of spiritual intelligence from Islamic perspective on emotional intelligence. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, 11(1), 216–232.

Ashmos, D. P., & Duchon, D. (2000). Spirituality at work: A conceptualization and measure. Journal of Management Inquiry, 9(2), 134–145.

Asutay, M. (2007). A political economy approach to Islamic economics: systemic understanding for an alternative economic system. Kyoto Bulletin of Islamic Area Studies, 1(2), 3–18.

Asutay, M. (2012). Conceptualising and locating the social failure of Islamic finance: Aspirations of Islamic moral economy vs. the realities of Islamic finance. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 11(2), 93–113.

Asutay, M. (2013). Islamic moral economy as the foundation of Islamic finance. In V. Cattelan (Ed.), Islamic finance in Europe: Towards a plural financial system. Edward Elgar.

Athar, M. R., Shahzad, K., Ahmad, J., & Ijaz, M. S. (2016). Impact of Islamic work ethics on organizational commitment: Mediating role of job satisfaction. Journal of Islamic Business and Management, 6(1), 119–134.

Ayoun, B., Rowe, L., & Yassine, F. (2015). Is workplace spirituality associated with business ethics? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 27(5), 938–957.

Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 248–287.

Barnett, C. K., Krel, T. C., & Sendry, J. (2000). Learning to learn about spirituality: A categorical approach to introducing the topic into management course. Journal of Management Education, 24(5), 562–579.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Baumgartner, H., & Steenkamp, J. (2001). Response styles in marketing research: A cross-national investigation. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2), 143–156.

Bhatti, K.O. (2015). Impact of Taqwa (Islamic Piety) on Workplace Deviance. PhD Dissertation. International Islamic University Malaysia.

Bhatti, O. K., Alam, M. A., Hassan, A., & Sulaiman, M. (2016). Islamic spirituality and social responsibility in curtailing the workplace deviance. Humanomics, 32(4), 405–417.

Bourne, H., & Jenkins, M. (2013). Organizational values: A dynamic perspective. Organization Studies, 34(4), 495–514.

Buana, G.K. (2013). Organizational spirituality as the mediator of the influence of individual spirituality to work attitudes. Unpublished Dissertation. Sebelas Maret University.

Cavanaugh, G. F. (1999). Spirituality for managers: context and critique. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 12(3), 186–199.

Cherrington, D. (1980). The work ethic: Working values and values that work. Amacom.

Choudhury, M. A. (2020). Unified model of global wellbeing as index of spirituality and socio-economic development: the Islamic economic approach. Journal of Social Sciences, 16(1), 63–71.

McLaughlin, C. (2009). Spiritual politics: Changing the world from the inside out. Random House Publishing Group.

Curry, J. P., Wakefield, D. P., Price, J. L., & Mueller, C. W. (1986). On the causal ordering of job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Academy of Management Journal, 29(4), 847–858.

de Klerk, J. J. (2005). Spirituality, meaning in life, and work wellness: A research agenda. The International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 13(1), 64–68.

Dean, K. L., Fornaciari, C. J., & McGee, J. J. (2003). Research in spirituality, religion, and work: Walking the line between relevance and legitimacy. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 16(4), 378–395.

Delbecq, A. L. (1999). Christian spirituality and contemporary business leadership. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 12(4), 345–349.

Duchon, D., & Plowman, D. A. (2005). Nurturing spirit at work: Impact on work unit performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 16, 807–833.

Freeman, L. C. (1978). Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Social Networks, 1(3), 215–239.

Fry, L. W. (2003). Toward a theory of spiritual leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 14(6), 693–727.

Gatling, A., Kim, J. S., & Milliman, J. (2016). The relationship between workplace spirituality and hospitality supervisors’ work attitudes: A self-determination theory perspective. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(3), 471–489.

Gheitani, A., Imani, S., Seyyedamiri, N., & Foroudi, P. (2019). Mediating effect of intrinsic motivation on the relationship between Islamic work ethic, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment in banking sector. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management, 12(1), 76–95.

Giacalone, R. A., & Jurkiewicz, C. L. (2003). Toward a science of workplace spirituality. In R. A. Giacalone & C. L. Jurkiewicz (Eds.), The handbook of workplace spirituality and organizational performance (pp. 3–28). M.E. Sharpe.

Giacalone, R. A., & Jurkiewicz, C. L. (2010). Handbook of workplace spirituality and organizational performance. Routledge.

Gümüşay, A. A. (2012). Knowledge & boundaries in a Sufi Dhikr circle. Journal of Management Development., 31(10), 1077–1089.

Gull, G. A., & Doh, J. (2004). The “Transmutation” of the organization: Towards a more spiritual workplace. Journal of Management Inquiry, 13(2), 128–139.

Hagger, M. S. (2015). Conservation of resources theory and the ‘strength’ model of self-control: Conceptual overlap and commonalities. Stress and Health, 31(2), 89–94.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tahtam, R. L., & Black, W. C. (2010). Multivariate data analysis a global perspective. Prentice Hall International Inc.

Harrison, D. A., Newman, D. A., & Roth, P. L. (2006). How important are job attitudes? Meta-analytic comparisons of integrative behavioral outcomes and time sequences. Academy of Management Journal, 49(2), 305–325.

Hashim, J. (2010). Human resource management practice on organisational commitment: The Islamic perspective. Personnel Review, 39(6), 78–799.

Hassan, M., Bin, N. A., Akhter, A., & Nisar, T. (2016). Impact of workplace spirituality on job satisfaction: Mediating effect of trust. Cogent Business & Management, 3(1), 1–15.

Hassi, A., Balambo, M. A., & Aboramadan, M. (2021). Impacts of spirituality, intrinsic religiosity and Islamic work ethics on employee performance in Morocco: The mediating role of intrinsic motivation. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, 12(3), 439–456.

Hawa, S. (2006). Almostaklas Fi Taziatul Anfos (The clarity in the purification of the souls). Dar-Alsalam.

Hefner, R. W. (2000). Civil Islam: Muslims and democratization in Indonesia. Princeton University Press.

Herzberg, F., Mausner, B., & Snyderman, B. B. (1959). The motivation to work. Wiley.

Hill, P. C., Pargament, K. I., Hood, R. W., McCullough, M. E., Swyers, J. P., & Larson, D. B. (2000). Conceptualizing religion and spirituality: Points of commonality, points of departure. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 30(1), 51–77.

Howard, S. (2002). A spiritual perspective on learning in the workplace. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 17(3), 230–242.

Ivancevich, J. M., Konopaske, R., & Matteson, M. T. (2005). Perilaku dan manajemen organisasi. Erlangga.

Jaramillo, F., Mulki, J. P., & Solomon, P. (2006). The role of ethical climate on salesperson’s role stress, job attitude, turnover intention, and job performance. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 26(3), 271–282.

Javed, B., Bashir, S., Rawwas, M. Y., & Arjoon, S. (2017). Islamic work ethic, innovative work behaviour, and adaptive performance: The mediating mechanism and an interacting effect. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(6), 647–663.

Kahnweiler, W., & Otte, F. L. (1997). In search of the soul of HRD. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 8(2), 171–181.

Kalemci, R. A., & Tuzun, I. K. (2019). Understanding protestant and Islamic work ethic studies: a content analysis of articles. Journal of Business Ethics, 158(4), 999–1008.

Kamil, N. M., Sulaiman, M., Osman-Gani, M. A., & Ahmad, K. (2011a). Implications of Taqwa on organizational citizenship behavior. In X. Osman-Gani & X. Sarif (Eds.), Spirituality in management from Islamic perspective. International Islamic University Malaysia Press.

Kamil, N. M., Al-Kahtani, A. H., & Sulaiman, M. (2011b). The components of spirituality in the business organizational context: The case of Malaysia. Asian Journal of Business and Management Sciences, 1(2), 166–180.

Karakas, F. (2010). Exploring value compasses of leaders in organizations: introducing nine spiritual anchors. Journal of Business Ethics, 93(1), 73–92.

Kazmi, A. (2004). A preliminary enquiry into the paradigmatic differences among the conventional and Islamic approaches to management studies. International Islamic University Malaysia Press.

Kidron, A. (1978). Work values and organizational commitment. Academy of Management Journal, 21(2), 239–247.

King, J. E., & Crowther, M. R. (2004). The measurement of religiosity and spirituality: Examples and issues from psychology. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 17(1), 83–101.

Kinjerski, V. M., & Skrypnek, B. J. (2004). Defining spirit at work: Finding common ground. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 17(1), 26–42.

Kolodinsky, R. W., Giacalone, R. A., & Jurkiewicz, C. L. (2008). Workplace values and outcomes: Exploring personal, organizational, and interactive workplace spirituality. Journal of Business Ethics, 81, 465–480.

Konz, G. N. P., & Ryan, F. X. (1999). Maintaining an organizational spirituality: no easy task. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 12(3), 200–210.

Krishnakumar, S., & Neck, C. P. (2002a). The “What”, “Why”, and “How” of spirituality in the workplace. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 17(3), 153–164.

Krishnakumar, S., & Neck, C. P. (2002b). The “what”, “why” and “how” of spirituality in the workplace. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 17, 153–164.

Lips-Wiersma, M. (2002). Analysing the career concerns of spiritually oriented people: lesson for contemporary organizations. Career Development Internasional, 7(7), 385–397.

Lumpkin, A., & Achen, R. M. (2018). Explicating the synergies of self-determination theory, ethical leadership, servant leadership, and emotional intelligence. Journal of Leadership Studies, 12(1), 6–20.

Luthans, F. (2006). Organizational behaviour: business and economics. McGraw-Hill.

Maclagan, P. W. (1991). From moral ideals to moral action: Lessons for management development. Management Education and Development, 22(1), 3–14.

Maham, R., Bhatti, O. K., & Öztürk, A. O. (2020). Impact of Islamic spirituality and Islamic social responsibility on employee happiness with perceived organizational justice as a mediator. Cogent Business & Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1787734

Manan, S. K., Kamaluddin, N., & PutehSalin, A. S. A. (2013). Islamic work ethics and organizational commitment: evidence from employees of banking institutions in Malaysia. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities, 21(4), 1471–1489.

Marques, J., Dhiman, S., & King, R. (2005). Spirituality in the workplace: Developing an integral model and a comprehensive definition. Journal of American Academy of Business, 7(1), 81–91.

Mayer, R. C., & Schoormn, F. D. (1992). Predicting participation and production outcomes through a two-dimensional model of organizational commitment. Academy of Management Jornal, 35(3), 671–684.

McCormick, D. W. (1994). Spirituality and management. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 9(6), 5–8.

McGee, P., & Grant, P. (2008). Spirituality and ethical behaviour in the workplace: Wishful thinking or authentic reality. Electronic Journal of Business Ethics and Organization Studies, 13(2), 61–69.

Miller, L. (1998). After their checkup for the body, some get one for the Soul. The Wall Street Journal, 20, 1.

Milliman, J., Czaplewski, A. J., & Ferguson, J. (2003). Workplace spirituality and employee work attitudes: An exploratory empirical assessment. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 16(4), 426–447.

Mitroff, L. I., & Denton, E. A. (1999). A study of spirituality in the workplace. Sloan Management Review, 40(4), 83–92.

Mohsen, N.R.M. (2007). Leadership from the Quran, operationalization of concepts and empirical analysis: relationship between Taqwa, Trust and Business Leadership Effectiveness. PhD Dissertation, Universiti Sains Malaysia.

Motahari, M. (2010). Management and leadership in Islam. Sadra Publications.

Mowday, R. T., Richard, M. S., & Porter, L. W. (1979). The Measurement of organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 14(2), 224–247.

Nasr, S. H. (1985a). Islamic spirituality: Manifestations. SCM Press.

Nasr, S. H. (1985b). Islamic spirituality: Foundations. Routledge.