Abstract

Compassion is acknowledged as a key motivational source of prosocial opportunity recognition (OR). This study examines the underlying processes of different types of compassion that lead to prosocial OR interventions designed to solve or ameliorate social problems. Self-compassion is associated with intimate personal experiences of suffering and encompasses a desire to alleviate the distress of others based on common humanity, mental distance and mindfulness. Other-regarding compassion is associated with value structures and social awareness and is based on a desire to help the less fortunate. Using a life-story analyses of 27 Israeli social entrepreneurs, we identified two OR process mechanisms, reflexivity (identifying overlooked social problems) and imprinting (identifying a known social problem within the social context). The relationship between these two types of compassion are equifinal, that is, both can lead to prosocial OR; however, the mechanisms differ. We contribute to the literature by showing that compassion serves as an internal enabler based on both cognitive and affective motivations for prosocial OR. We introduce a theoretical perspective that establishes a process model for further research on the role of compassion in identifying and leading prosocial action.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Interest in the role of compassion and prosocial motivation has increased over the last decade, both in commercial entrepreneurship (Köllen, 2016; Shepherd, 2015; Wry & York, 2017) and social entrepreneurship (Miller et al., 2012; Pless, 2012; Shepherd & Williams, 2014; Simpson et al., 2014; Yitshaki & Kropp, 2016a, b). However, with few exceptions, most of the research has been theoretical or intuitive. This study empirically examines the role of compassion in motivating social entrepreneurs. We seek to understand why some individuals dedicate their entire careers primarily to assist others.

Grimes et al. (2013) conceptualized compassion as “a distinct motivated reasoning process that complements traditional theories of entrepreneurship” (p. 460). Compassion can be viewed as a three-part process that involves noticing other’s suffering, developing affective feelings toward the suffering, then taking action (Dutton et al., 2014; Kanov et al., 2004; Köllen, 2016). The desire to expend effort to benefit other people is a key component of prosocial motivation (Batson, 1987; Cha et al., 2014; Grant, 2008; Miller et al., 2012) and ethical behavior (Lewis, 1985). Compassion can help identify prosocial opportunities to alleviate the suffering of others in the context of kinship relations (Maner & Gailliot, 2007), as a way to alleviate personal suffering (Shepherd & Williams, 2018) or to protect the welfare of individuals, groups or organizations (Lumpkin & Bacq, 2019). Compassion can be viewed as the behavioral manifestation of voluntary actions to benefit others (Simpson et al., 2014).

Compassion is important in entrepreneurship as it can help explain social entrepreneurial intentions (Bacq & Alt, 2018) and identify prosocial opportunities. Examples include the desire to alleviate others’ suffering after disaster events or catastrophe (Rodriguez et al., 2006; Williams & Shepherd, 2016) and a desire to alleviate poverty (Sutter et al., 2019). Social entrepreneurs (SEs) are motivated to alleviate suffering of others rather than primarily focusing on their own financial interests (Pan et al., 2019; Santos, 2012). SEs identify prosocial opportunities and caring actions to generate social impact (Agafonow, 2014; André & Pache, 2016; Dey & Lehner, 2017).

However, the role of compassion as a motive that leads to prosocial opportunity recognition (OR) has been overlooked (Saebi et al., 2019). Zahra and Wright (2016) point out that the ways in which “entrepreneurs learn to discover and create opportunities remains an unanswered research question” (p.624). The entrepreneurship literature focusses largely on goal setting that examines self-efficacy and task performance, often utilizing a cost–benefit analysis (De Dreu et al., 2000; Hechavarria et al., 2012; Locke, 2000; Meglino & Korsgaard, 2006) that is largely ineffective in understanding the motivations of SEs. Understanding compassion’s role in prosocial OR can help clarify the mechanism through which social opportunities are identified (De Clercq & Honig, 2011) and lead to understanding how best to support social entrepreneurship (André & Pache, 2016; Montgomery et al., 2012).

SEs are a heterogeneous group driven by different ethical and social incentives and constraints, pursuing different entrepreneurial models (Mair et al., 2012). They are less concerned with creating economic value or personal status and more interested in providing public goods and solving social problems (Agafonow, 2014). From an ethical perspective, they engage in practices that are both motivated by individual ethics, and also constrained by external demands. SEs facilitate social change through empowerment (Haugh & Talwar, 2016; Siqueira & Honig, 2019), by identifying and bridging opportunities that yield high value (Pless, 2012) and by operating outside the boundaries of traditional competitive firms (Dees, 2012; Siqueira et al., 2020). Their ethical decisions are not without conflict and comprise concessions that are rarely examined in the literature (Mitzinneck & Besharov, 2019).

In practice, SEs undertake activities and processes to identify social problems and to provide innovative solutions (Austin et al., 2006). Martin and Osberg (2007) describe SEs as those who identify “a stable but inherently unjust equilibrium that causes the exclusion, marginalization, or suffering of a segment of humanity that lacks the financial means or political clout to achieve any transformative benefit on its own” (p. 35). The SE then acts to correct this imbalance, enhancing the well-being of the target group or society as a whole (André & Pache, 2016). Growing worldwide inequality certainly presents important opportunities for SE (Piketty, 2013). Related issues exacerbated by growing inequality include (but are not limited to) poverty, marginalization of disadvantaged social groups, discrimination of LBGTQ populations, discrimination against immigrants, spousal abuse, tending to the needs of intellectually and physically disadvantaged individuals, feeding the hungry, and the effects of inequality on general health and well-being.

This paper addresses calls to empirically examine the role of compassion as a prosocial motivator for SEs by comparatively examining the processes through which compassion precedes the recognition of prosocial opportunities, leading to helping, benefiting and empathizing with others (Grimes et al., 2013). We used the sensemaking framework as it allowed us to understand SEs perceived ambiguity and uncertainty associated with interpreting social inequalities and taking actions to alleviate others suffering. Sensemaking is particularly suitable in that it is capable of dynamically linking the processes integrating both compassion and social justice (Shahzad & Muller, 2016). We focus on SEs sensemaking of compassion-organizing processes as they provide an understanding of the retrospectively cognitive and emotional reasoning through which SEs identify prosocial opportunities and decide to establish prosocial new ventures (Cornelissen & Clarke, 2010; Sandberg & Tsoukas, 2020). Our research goal is to understand how SEs sensemaking of compassion-organizing processes lead them to identify prosocial opportunities, as well as identifying the OR mechanisms associated with these prosocial actions based on different types of compassion. Although we follow multiple ventures and their directions, our main focus is on understanding the motivations and processes undertaken by the individual social entrepreneur.

Using established grounded-theory, complemented by abduction methods, we develop a theory of the role of compassion in shaping OR processes. This study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, it extends the literature on compassion as prosocial motivation (Martin et al., 2015) by distinguishing between self-compassion and other-regarding compassion, reflecting different paths to prosocial OR. Second, the study contributes to the literature on the OR process (e.g., Davidsson, 2015; Ramoglou & Tsang, 2016) by showing the importance of reflexivity or imprinting mechanisms. Third, this study examines both affective and cognitive components. All together, our findings show that compassion serves as a mechanism enabling individuals to challenge the profit-maximizing entrepreneurial norms by creating new self-compassion opportunities (De Clercq & Honig, 2011; Martin et al., 2015). Finally, we provide a process model and define OR in the social entrepreneurship arena, useful for targeting potential SEs for support and promotion.

This paper is organized as follows: we begin with a theoretical overview of compassion as an antecedent to prosocial behavior, before discussing OR and the implications of compassion on OR. After introducing our methods, we unpack our observations leading to new theoretical insights and a process model showing how SE compassion impacts OR. Our conclusion includes implications for both scholars and public policy actors.

Compassion as an Antecedent to Prosocial Behavior

Compassion can motivate SEs to create social value in order to alleviate suffering (Kroeger & Weber, 2014). Compassion involves emotional energy, as it elicits feelings and distress that lead to a desire to reduce the suffering of others (Miller et al., 2012). As a process, compassion involves awareness, emotions, sensemaking, and action taken to alleviate the anguish of others (Dutton et al., 2014). The process is multi-dimensional, and covers a wide range of affective, cognitive, and behavioral constructs and behaviors (Martin et al., 2015). It consists of three sub-processes: noticing others’ suffering (cognitive), feelings regarding others (affective), and responding (behavioral) (Dutton et al., 2006). Compassion can trigger collective action (Barberá-Tomás et al., 2019), as it is associated with the generalizability of social issues from an individual’s suffering to a community’s needs (Miller et al., 2012).

From a psychological perspective, compassion consists of two kinds of feelings, sympathy and empathy, that may serve as antecedents of compassionate behavior (Gruen & Mendelsohn, 1986). Sympathy refers to “the heightened awareness of the suffering of another person as something to be alleviated” (Wispé, 1986, p. 318). Empathy refers to “the attempt by one self-aware self to comprehend unjudgmentally [sic] the positive and negative experiences of another self” (Wispé, 1986, p. 318). Thus, compassion may be rooted in a general sense of empathy toward others based on one’s own similar life experiences. Alternately, sympathy can be based on understanding and relating to others’ suffering (Wispé, 1986). Both empathy and sympathy can be viewed as correlates to compassion as they may evoke feelings and responses to others’ suffering (Dutton et al., 2006; Shepherd, 2015).

The compassion literature identifies two important sub-categories: self-compassion and other-regarding compassion. Self-compassion is an inner process oriented toward an individual’s desire to alleviate his/her own suffering based on self-awareness (Neff, 2003a). Neff (2003b) suggests that self-compassion contains three basic components relevant to social entrepreneurship: “(1) extending kindness and understanding to oneself rather than harsh self-criticism and judgment; (2) seeing one’s experience as part of the larger human experience rather than as separating and isolating; and (3) mindfulness and holding one’s painful thoughts and feelings in balanced awareness rather than over-identifying with them” (p. 234). Neff (2003a) describes self-compassion as being touched and open to one’s suffering, rather than disconnecting from it. Self-compassion is associated with actions to increase multiple aspects of one’s well-being, both hedonic and virtuous, that can include emotional stability, positive emotions and relationships, resilience, and self-esteem (Huppert & So, 2013; MacBeth & Gumley, 2012). Moreover, self-compassion can lead to proactive behavior to better one’s situation over time rather than to passively accept it (Neff, 2011).

Lilius et al. (2011) describe other-regarding compassion as compassion where a person notices another person’s suffering, feels sympathy and responds to the suffering. It is based on values or heightened awareness of other’s suffering generated by witnessing another person in need (Batson & Coke, 1981; Ryan & Deci, 2001), thus creating a desire to help them reduce their distress and enhance their well-being (Schroeder et al., 1988). Other-regarding compassion contains an awareness of another’s pain and a desire to alleviate the suffering of people who are less fortunate (Dutton et al., 2006; Shepherd & Williams, 2014; Williams & Shepherd, 2016).

Prosocial action is defined as “the desire to benefit others or expend effort out of concern for others” (Bolino & Grant, 2016, p. 602). Prosocial theory posits that individuals may act to increase the welfare of others using instrumental rationality (De Dreu et al., 2000; Meglino & Korsgaard, 2006), based on intentions and motivations to promote prosocial actions (Bacq & Alt, 2018; McMullen & Bergman, 2017). Although compassion is acknowledged as a prosocial motive, the differences in motivation from values and self-concern are unclear (Bolino & Grant, 2016).

While compassion can motivate SEs (Ramoglou & Tsang, 2016), the processes through which compassion leads to the identification of social opportunities remains unclear (Saebi et al., 2019; Zahra & Wright, 2016). On the whole, the literature on prosocial behavior focuses on a general desire to benefit others based on rational considerations (Cha et al., 2014), possibly derived as an outcome of goal setting theory (De Dreu et al., 2000; Hechavarria et al., 2012; Locke, 2000; Meglino & Korsgaard, 2006). In contrast, compassion theory implies that the desire to alleviate another’s suffering is associated with internal processes that may be linked either to self- or other-regarding compassion (Rynes et al., 2012). Compassion theory explains prosocial behavior in terms of achieving psychological well-being. We focus on compassion in the context of social entrepreneurship as a distinctive form of motivation that can explain the relationship between entrepreneurial motivations and prosocial OR (Grimes et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2012). Although compassion is not a prerequisite for all social ventures, compassion can be an important motivational factor for SEs (Ramoglou & Tsang, 2016). Thus, understanding the motivational importance of compassion can lead to better promotion and development of SE activity.

Opportunity Recognition and Prosocial Behavior

There are many definitions of OR for commercial entrepreneurship, viewing it as either deterministic (Ramoglou & Tsang, 2016), or as a dynamic process transforming over time (Berglund & Korsgaard, 2017). Some scholars argue that entrepreneurs identify new opportunities based on their subjective beliefs leading to actions (Foss & Klein, 2020), while others argue that OR is subject to external enablers (Davidsson et al., 2018). Most existing literature views OR through a cognitive lens based on a systematic search for new opportunities (e.g., Grégoire et al., 2011; Mitchell et al., 2007) based on prior knowledge (Mitchell et al., 2002; Shepherd & DeTienne, 2005) whereby ethical considerations are typically absent.

Alvarez and Barney (2007) differentiate between discovered and created opportunities. The former result from systematic scanning of the environment and are considered objective in nature; opportunities can be discovered as a result of exogenous shocks in the environment. Entrepreneurs who discover new opportunities are more alert to their environments and identify existing opportunities. Antithetically, created opportunities are endogenous enactment actions taken by entrepreneurs who identify new opportunities based on exploration and iterative processes (Foss & Klein, 2020). By acting, entrepreneurs create “opportunities that could not have been known without the actions taken by these entrepreneurs” (Alvarez & Barney, 2007, p. 15). Suddaby et al. (2015) suggest that opportunities can be identified through two mechanisms: imprinting and reflexivity. In imprinting, opportunities are embedded within the social, political and economic environment (Marquis & Tilcsik, 2013) and are based on ongoing interactions within the social context (Simons & Roberts, 2008). In contrast, reflexivity mechanisms are less bounded by social constraints. Opportunities are generated by subjective and interpretive reflection of entrepreneurs, who use their thoughts, imagination and feelings to create social realities (Ramoglou & Tsang, 2016). An entrepreneur’s emotional behavior and activities are associated with collective emotional arousal, collective reflexivity and entrepreneurial opportunities (Jennings et al., 2015). Certainly, a definition of OR for social entrepreneurship represents a first step in evaluating their effectiveness.

We were unable to identify a definition of OR in the social entrepreneurship arena. Collectively, the conceptualizations of social entrepreneurship embody activities and processes to identify social problems and to provide innovative solutions. Drawing on Austin et al.’s (2006) definition of social entrepreneurship, Martin and Osberg’s (2007) activities of a SE, and Alvarez and Barney’s (2007) work on OR, we provide the following definition: A social entrepreneur’s opportunity recognition, whether discovered or created, involves the identification of unmet social needs, with the goal of developing an innovative solution to create social value in order to fulfill those unmet needs. Ethical considerations in the form of social needs are thus a foundation of SE OR.

While it is not always clear how entrepreneurs combine cognitive and affective processes and associated mechanisms to identify new opportunities (Suddaby et al., 2015), compassion is overlooked. Compassion has both affective and cognitive components that motivate SEs to identify prosocial opportunities (Lilius et al., 2011; Neff, 2003a, 2003b) and may inspire an identity-based motivation related to the values and beliefs that are central to SEs self-concept. OR, in the social entrepreneurship arena, is based on novel approaches to addressing social problems (Austin et al., 2006; Phills et al., 2008). With few exceptions (e.g., Orser et al., 2013; Yitshaki & Kropp, 2016a, 2016b), little is known regarding how affect serves as an antecedent of OR and the associated mechanisms and processes through which prosocial opportunities are discovered and manifested (McMullen & Dimov, 2013).

Entrepreneurs’ narratives can provide an understanding of how past and present cognitive and affective stimuli set up a foundation for understanding the relationship between entrepreneurial motivations and OR (McMullen & Dimov, 2013). Our study addresses the understanding of compassion as motivation to prosocial opportunity recognition, adding to both the compassion and OR literatures.

Sensemaking and Prosocial Behavior

Within the social entrepreneurship context, SEs establish new ventures based on their deep commitments to social missions that inspire and motivate them (Smith et al., 2013). SEs can also have dual missions that combine commercial and social goals. While some ventures tend to emphasize either social or commercial strategies, other may generate a coherent centrality of both (Dees, 2012; Jones & Donmoyer, 2015). Although there may be overlapping motivations in the for-profit and social entrepreneurial domains, we anticipate that the social mission of SEs eclipse their aspirations for monetary gains. For this reason, understanding the process of motivation and OR leading to action is critical for the effective promotion of SE.

To study compassion we must account for subjectivity, including ‘after the fact’ sensemaking by comparing the account of events as experienced by participants and the different stakeholders involved. This requires an iterative process of sensemaking at the onset, sensegiving through influence, sensemaking through mutual understanding and cognition, and finally sensegiving through influence and action (Gioia & Chittipeddi, 1991).

Sensemaking “involves the ongoing retrospective development of plausible images that rationalize what people are doing” (Weick et al., 2005, p. 409). Sensemaking is a cognitive as well as a social process triggered by cues such as events or crisis situations (Maitlis & Christianson, 2014; Maitlis & Sonenshein, 2010). These situations disrupt individuals’ understanding of the world and lead them “to ask what is going on, and what they should do next” (Maitlis & Christianson, 2014, p. 70). Therefore, sensemaking is associated with actions and motivations taken by actors (Gioia & Chittipeddi, 1991; Maitlis & Christianson, 2014; Weick, 1988).

Analyzing actors sensemaking processes can provide an understanding of the reasoning and emotional process implicit to their actions. It can provide an understanding of the immanent meaning (Sandberg & Tsoukas, 2020) of an inner calling for taking actions reflect a purpose in life (Hall & Chandler, 2005; Schabram & Maitlis, 2017). Career calling derives from an inner direction of meaning that offers the possibility of improving the world (Bellah et al., 1996). It can be viewed in a religious context (Weber 1958) or secularly, as a deep-seated desire to help others. Individuals motivated by career calling may be more self-aware and more adaptable to answer the call (Hall & Chandler, 2005).

Zahra and Wright (2016) identify that “entrepreneurs are the sense makers who define and pursue opportunities without a mandate from stakeholders” (p. 611). In this study, we examine the process of sensemaking of SEs’ using life-stories methodology that includes multiple episodes within SEs’ life experiences and compassion-based considerations that lead them to take action (Sandberg & Tsoukas, 2015). SEs’ stories represent an additional subjective and emotional dimension that involves taking actions that deviate from the current social order (Downing, 2005; Sandberg & Tsoukas, 2020). SEs’ stories reflect inductive sensemaking processes associated with an identification of a meaningful opportunity and new venture creation (Cornelissen & Clarke, 2010). The stories enable an exploration of the motivations and meanings SEs attribute to their identification of unmet prosocial needs (Gartner, 2007; Ibarra & Barbulescu, 2010; Lieblich et al., 1998; Weick, 2012). In turn, the narratives enable understanding the patterns that occured over time as part of the structure of the story (Pentland, 1999; Williams, 2001). This approach provides an understanding of SE’s subjective experiences and expressions (Peacock & Holland, 1993) that represent the emotional processes associated with compassion, which is a missing link within the sensemaking perspective (Sandberg & Tsoukas, 2015). SEs’ stories thus serve as a source to understand their actions based on retrospective sensemaking of their life events and past experiences (Gephart et al., 2010; Cornelissen & Clarke, 2010).

Methodology

We used the life-stories method to examine compassion as a source of prosocial OR among SEs. The life-stories method examines how respondents refer to past, present and future events (Hytti, 2005; Lieblich et al., 1998; McAdams, 1999; McKenzie, 2005; Rae, 2005). It provides an understanding of how a narrator locates his or her self in time and space and gives meaning to the processes that link life events and actions (Maclean et al., 2012). This allowed us to understand how entrepreneurs make sense of their cognitions, emotions and actions. In the context of entrepreneurship, the life-stories perspective enables examination of how SEs integrate their past experience in a coherent plausible way, using thoughts and emotional expressions (McKenzie, 2005; Mitchell, 1997; Rae, 2005). The stories are an important source of SEs’ sensemaking (Weick, 1995) as they explore the respondents’ activities (Gartner, 2007). The stories provide rich insights about entrepreneurial processes (Downing, 2005).

Rather than focusing on static variances, our study examined dynamic processes consisting of a “constant flux, where individuals and environments are mutually constitutive” (Bansal et al., 2018, p. 1191). Accordingly, we sought to explore the processes through which SEs used their sensemaking of compassion and understandings to leverage prosocial opportunities. This facilitated the understanding of dynamic processes between SEs cognition and emotions (Bansal et al., 2018; Shahzad & Muller, 2016). Moreover, by analyzing SEs life stories we were able to examine the underling ‘structure, coherence, sequencing’ and purpose of their activities. We studied how SEs narratives were associated with the meaning of their actions and the social construction of their actions (Rantakari & Vaara, 2017). As presented in the theoretical overview, previous studies differentiate between different types of compassion-organizing processes (Neff, 2003a; Wispé, 1986). However, self and other-oriented compassion were not examined jointly, with OR by SEs’. In that sense, our methodology focuses on examining the parallel trajectories between the two sub-process and SEs prosocial actions (Cloutier & Langley, 2020).

Sampling and Data Collection

We used a purposeful sampling approach to include varied categories of ventures that operate in the social entrepreneurship arena (Suddaby, 2006). Specifically, we employed criterion sampling, in which the cases meet an important predetermined criterion (Patton, 2005), a different foci of activity. Respondents were identified through networking and personal connections. Initially, 32 life stories were systematically collected through in-person interviews; however, five of these did not meet the criteria of true SEs, i.e., those who aim to create social value using an innovative approach to solve social problems (Austin et al., 2006), and were thus omitted. To ensure a wide variety of activities, the final sample is based on 27 social ventures that operated in 9 different categories of activities. These included activities such as marginalization of disadvantaged social groups, discrimination of LBGTQ populations, spousal abuse, tending to the needs of intellectually and physically disadvantaged individuals, feeding the hungry, among others (please see Table 1 for further elaboration). As highlighted by Corbin and Strauss (1990) all important concepts were identified in each story. Using a multi-case approach is considered to be an effective approach for theory building (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007; Langley, 1999). This approach allowed us to analyze the concepts of compassion and OR within and across cases as suggested by Eisenhardt (1989). Descriptions of the respondents, type of activity and data collected about each venture appear in Table 1. We tracked social ventures through the National Ministry of Justice site to understand the social ventures form. Most social ventures in our data were not-for-profit oriented. As well, their budgets were derived mainly from tax exempted donations. Only a few ventures reported a small portion of income from services they provided compared to incomes they received from donations.

Data were collected in two stages. The first set was in-person interviews conducted in Hebrew with 32 SEs by graduate students. The students were trained by the authors in the life-stories methodology. This training was supported by a research protocol that included guidelines for the interviews, including a request to pay attention to SEs story flow and the need to clarify the associations they made between thoughts, beliefs and actions. SEs were asked to discuss their motivations and their ventures in any way they liked. They described their personal story/history and its relation to present actions. Each interview lasted 90–120 min. All were tape-recorded and later transcribed verbatim. The initial rounds of analysis were performed in Hebrew by the first author; subsequently, the transcripts were translated to English.

After three rounds of data analysis (please see Table 2) we realized that additional clarifications were needed to better understand SEs compassion, organizing processes and prosocial OR. Corbin and Strauss (1990) stated that when distinctions among categories are identified, “Ambiguities can be resolved through additional field work and specification” (pp. 12–13). We conducted follow-up interviews with five SEs who differed in compassion-based motivations in order to obtain a deeper understanding of the initial patterns of sympathy and empathy that emerged in previous stages of the analysis.

The follow-up interviews were characterized by narrative repetitions and high coherence between the sequence of events, self-reflections and the processual dynamics between SEs’ compassion and OR processes (Bansal & Corley, 2012; Dailey & Browning, 2014; Gubrium & Holstein, 1998). We complemented this with content analysis of data collected from SE sites, Facebook pages, videos and newspaper articles to obtain more information about how the opportunity evolved over time. Yin (2003) recommends that analyses of case studies include chains of evidence that enable external observers to understand how conclusions were derived from all sources of data. This additional step was conducted to provide confidence in the reliability and validity of the results (Creswell & Miller, 2000; Morse et al., 2002). The additional data were consistent with the in-depth stories told by SEs and allowed clarification about the different types of compassion-based processes identified in the three first rounds of the data analysis. We also gained a better understanding about the association SEs made between their compassion-based process and the mechanisms through which they were able to identify prosocial opportunities. We could also identify how SEs manifested their compassion to evoke social awareness among others.

The multiple stages of data collection enriched our understanding of each life story at the individual level, and of the actions taken by the SEs at the venture level. It allowed us to avoid overreliance on a single methodological approach (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007), which is common in the field of social entrepreneurship research (Dacin et al., 2011). The triangulation of methods enabled us to gain a more complete understanding of compassion as a prosocial motivation for OR (Turner et al., 2017) and to validate the themes that emerged; it also provided richer and more reliable descriptions of each case (Denzin, 1989; Graebner & Eisenhardt, 2004; Jick, 1979; Yin, 2003). Finally, it also reduced the risk of retrospective construction of new memories (Loftus & Hoffman, 1989), thus contributing to the reliability of the data.

Data Analysis

We used a multiple-stage approach to analyze the interviews and to develop theory. This was an iterative process that evolved out of the insights gained in each preceding stage of data analysis. Following Srivastava and Hopwood (2009), “reflexive iteration is at the heart of visiting and revisiting the data and connecting them with emerging insights, progressively leading to refined focus and understandings” (p. 77). As the stages of the data analysis evolved, we discovered other layers of the nature of compassion, the sensemaking of SEs and mechanisms through which prosocial opportunities were identified and pursued.

In all stages of analysis, we employed an open coding approach, as recommended by Corbin and Strauss (1990). We considered each story as a whole, following its inner consistency, and conducted cross-story analysis to identify common patterns. Our initial intention was to reveal the compassion-organizing and OR processes based on an inductive approach (Eisenhardt, 1989). We sought to better understand compassion processes and to generate a theoretical conceptualization of how SEs construct meaning and make an association between their compassion and prosocial OR (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007; Langley, 1999; Strauss & Corbin, 1994; Suddaby, 2006; Zahra, 2007). During the data analysis stages, we reached a point in which compassion and OR perspectives could not explain the interrelations between SEs compassion-organizing and the underlying OR mechanisms (Mayer & Sparrowe, 2013). Therefore, we employed a mixture of inductive and abductive methods to explain the association between compassion and prosocial OR, adding to theory based on an integration between two theoretical perspectives (Kovács & Spens, 2005; Mayer & Sparrowe, 2013; Van de Ven, 2016; Bamberger, 2018). Table 2 summarizes the development of different stages of our data analysis.

In the first stage, each interview was analyzed separately, based on the meaningful life events described by the SE. The goal was to consider each story’s flow and to develop an understanding of the references made by the respondent. We paid particular attention to how SEs explained their feelings of compassion and the cognitive reasoning of the opportunity they recognized. Each narrative was examined with respect to the internal coherence of the story, the meanings SEs assigned to their actions, and the subjective interpretations in each part of the stories (Cassell & Symon, 1994). Giving weight to the inferences and interpretations of meanings that respondents describe enables an understanding of the implicit dimensions of their story (Lieblich et al., 1998). The themes identified in this stage provided an initial understanding of the patterns that emerged from the data. These patterns can be considered as a pre-understanding stage (Gummesson, 2000), providing a basis for further analysis.

In the second stage, we reanalyzed each story, this time focusing on references to the SEs’ compassion in an attempt to identify its sources. Two types of compassion narratives, reflecting two sources of compassion, emerged: (1) Empathy—the desire to alleviate others suffering based on SEs’ own experiences and, (2) Sympathy—the desire to alleviate others suffering based on social awareness and value structure. We further searched for similar themes that emerged across the stories and performed a comparative analysis of the above-mentioned compassion types as a source of meaning of SE actions (Gephart, 2004; Suddaby, 2006). At this stage of the inductive analysis, we identified that SEs’ compassion reasoning was broader than just a desire to alleviate others suffering as suggested by Miller et al. (2012). We were able to identify that the desire to alleviate others suffering was based on a mix of considerations.

As we proceeded with the data analysis, in the third stage we rigorously analyzed SEs cognitive and emotional sensemaking to alleviate suffering. We identified that the source of SE compassion falls into one of two categories: self-compassion and other-regarding compassion. SEs in the self-compassion category experienced the same or a similar type of suffering as the people they were trying to help. Building on the psychological literature (Neff, 2003a, 2003b), we identified that self-compassion-organizing processes were based on an understanding of SEs suffering in the present or the past as part of a common humanity. SEs sensemaking was based on mental distance and mindfulness, enabling them to understand their suffering retrospectively and make a decision to alleviate others suffering based as a way to heal. We were also able to identify that other-regarding compassion is based on SEs social awareness and value structure (Dutton et al., 2006; Lilus 2011). At the fourth stage, after reanalyzing and combining the data from the follow-up interviews and secondary data, we were able to identify commonalities across different stories. At this stage of our analysis, we combined inductive and abductive methods to make sense of the observations in order to develop theory. We extended the understanding of compassion-based motives beyond the common understanding suggested by the entrepreneurship and organizational literature. At the same time, we found that SEs compassion-organizing processes are similar to those suggested by the psychological literature (Bamberger, 2018).

At the fifth stage, we were able to obtain a better understanding about SE processes at both the individual and the venture levels of analysis. We identified two sensemaking considerations associated with each type of compassion. SEs motivated by self-compassion explained the prosocial opportunities identified based on sensemaking of knowing (Sandberg & Tsoukas, 2015). It reflects an understanding from within (Dodge et al., 2005; Shotter, 2006) based on tacit and practical knowhow about ways to alleviate others’ suffering (Ambrosini & Bowman, 2001). SEs motivated by other-oriented compassion explained the prosocial opportunities they identified be making sense of their ability of helping others by alleviating their suffering.

In the next steps of data analysis (stages six and seven), we identified paths between the different types of compassion and underlying assumptions of knowing and helping created or discovered OR, based on reflexive or imprinting mechanisms (Alvarez & Barney, 2007; Suddaby et al., 2015). Reflexivity is more subjective and interpretative and is based on the SE’s thoughts, imagination and feelings; imprinting is more objective and is embedded within the social, political, and economic environment (Suddaby et al., 2015). We coded each path separately with regard to each venture and then reanalyzed each pattern identified as a whole.Footnote 1 Next, we searched for commonalities across stories and were able to delineate a path between different types of compassion-based processes and OR mechanisms. This stage of analysis was based on the combination of inductive and abductive methods. Finally, we generated a process model that reflects how different types of compassion-based processes lead to prosocial actions via different and similar OR mechanisms.

As shown in Table 2, the interplay between inductive and abductive methods enabled us to explore SEs sensemaking of compassion as a motivational construct. The inductive components of the data analysis focused on exposure of the underlying emotional and cognitive processes of the different types of compassion organizing. Similarly, we also revealed how each type of compassion was associated with prosocial OR processes. The abductive components were associated with a comparative analysis between the themes that emerged and theory building based on an integration between compassion and OR theories to explain how different types of associated organizing processes lead via different OR mechanisms to prosocial OR. Overall, our data analysis revealed parallel processes based on the bifurcation of different types of compassion-organizing processes and different OR mechanisms that lead to prosocial actions through different trajectories (Cloutier & Langley, 2020).

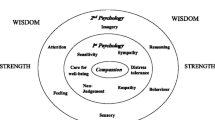

Figure 1 presents the systematic data structure of our data analysis (Gioia et al., 2012; Pratt et al., 2006) and the sensemaking of SEs’ compassion and consideration in taking prosocial actions (Clark et al., 2010).

Findings

We found that both self- and other-regarding compassion play a major role in shaping prosocial OR among SEs. SEs motivated by self-compassion demonstrate compassion-organizing processes based on common humanity, mental distance and sensemaking of knowing (Cunliffe & Scaratti, 2017) regarding how to alleviate others’ suffering, generated by an intimate understanding through personal experience and empathy. SEs motivated by other-regarding compassion demonstrate compassion-organizing processes based on noticing and feeling and a desire to alleviate suffering and sensemaking of helping (Selsky and Parker 2010) through social awareness and values structure.

In both types of compassion, we were able to distinguish different mechanisms to identify prosocial opportunities based on imprinting and reflexivity. Reflexivity is based on affective processes rather than a deliberate cognitive search while imprinting mechanisms are based on opportunities embedded within the social, political and economic environment. Importantly, while there are different paths and processes from self- and other-regarding compassion to OR, the result is equifinal: both types of compassion ultimately lead to similar types of prosocial OR. For elaborated case analyses demonstrating the organizing processes of self-compassion and other-regarding compassion and their separate paths to OR, see Appendices 1A and 1B.

Self-compassion

Fifteen SEs had intimate experiences with suffering. All discussed their self-compassion and similar compassion-organizing processes. They referred to (1) the story of their suffering; (2) understanding others’ needs based on personal experiences and being part of a common humanity; and (3) mental distance and mindfulness. These SEs are motivated by their own suffering and a desire to find solutions for others, based on the same or closely-related problems that they themselves experienced. For illustrative examples of self-compassion quotes and mechanisms through which the opportunities were recognized, see Table 3.

In 12 of the 15 cases of self-compassion, SEs’ suffering was based on past experiences, providing time for mental distance and mindfulness as well as a balanced awareness of their own suffering and the suffering of others. For example, NV (entrepreneurship education for women) said, “It took me a long time to understand that the most traumatic event in my life would be the most constructive event in my life… I decided to establish the venture to help women who didn’t have extensive support from their family… a venture that would help women to help themselves by establishing their own businesses.”

In three cases, SE’s self-compassion was based on current suffering. They were coping with their own suffering and noticed that there were others in similar circumstances who were also suffering. For example, ZP (daycare center for children with disabilities), who couldn’t find suitable educational programs for his own child, said, “We saw that there are many parents who face the same problem…. Yet, we couldn’t convince the authorities to put all these children together. …we were lucky to get assistance from good people and volunteers.” Self-compassion focused on common humanity and mindfulness, as the SEs were motivated to alleviate their own suffering through collective action. Self-compassion led to creating a community that strengthened both the SEs and similar others and enhanced their ability to cope with the suffering.

A major theme that emerged is the transformation of current life events into prosocial action as a way to heal both the SEs themselves and other people. SEs described their activity as empowering. Even though they were suffering, they became healers rather than victims. For example, EBZ (providing wigs to cancer patients), who is also a cancer patient, described his activities as therapeutic, leading to his own rehabilitation as well as to that of his beneficiaries.

In sum, self-compassion is an antecedent of OR and the processes are shaped by the timing of the suffering. Self-compassion toward suffering in the past is associated with mental distance and processing of the suffering. SEs who experienced some degree of recovery were more mindful and saw their suffering as part of common humanity. SEs who experienced suffering in the past identified a sense of rehabilitation associated with their ability to take action to correct their past helplessness. Thus, mental distance and mindfulness are associated with a time lag between SE suffering and the desire to alleviate another’s suffering. In contrast, self-compassionate SEs coping with suffering in the present associated the desire to alleviate their own present suffering and that of others with a sense of healing. Healing and well-being are part of SEs’ compassion-organizing processes, as well as a possible result of taking prosocial action. Within this context, self-compassion led to OR based on reflexive mechanisms, i.e., sensemaking through personal experience, and self-compassion based on imprinting mechanisms, i.e., sensemaking through empathy.

Self-Compassion Based on Reflexivity Through Personal Experience

Ten SEs identified opportunities through reflexive mechanisms. OR in this category was based on affective processes rather than a deliberate cognitive search for the opportunity. There is a relationship between an SE’s own suffering and the desire to alleviate the suffering of others in similar circumstances (see Table A2A for illustrative quotes). An SE’s compassion derives from his or her own experience, combined with a deep understanding of what people with similar experiences feel and need. The process entails creating a unique solution to an opportunity that would not have been identified or exploited by others.

NA runs a social venture that employs people with disabilities to create gifts for special occasions (for his detailed story, see Appendix 1A). As a child, NA witnessed his father’s battle with trauma after the Yom Kippur War.Footnote 2NA identified his past experiences as the trigger to becoming socially active. His compassion was based on an intimate experience with suffering in the past. However, NA did not become an SE until he visited a factory that employed people with disabilities that reminded him of his own experiences. His self-compassion was based on his understanding of and kindness toward his own suffering and the way it influenced his family life. NA’s mindfulness transformed his compassion into prosocial action. His motivation is to prevent others from suffering as he did, to alleviate their suffering, and to transform his past events into a collective action. For NA, understanding the source of his compassion is retrospective; he sees himself as an agent responsible for addressing the social problem he identified. NA transformed his suffering to personal healing by alleviating his own distress and rehabilitating himself.

OF, whose venture provides support to victims of sexual abuse, was herself sexually abused as a child by a family member. She wanted to identify and help children who were being abused and was unhappy with existing government programs. Her suffering demonstrates a feedback loop between self-compassion and collective compassion. She told her story at a fundraising event and described how people were motivated to donate money and become involved.

Some SEs identified social opportunities based on their suffering in the present. EBZ was a hairdresser before he was diagnosed with cancer. On the first day of treatment, he saw a woman crying at the hospital. She told him she was crying because the chemotherapy would cause her to lose her hair. He reassured her that he would help her by cutting her hair and making her a wig. The opportunity was recognized and the venture began. At first his wife drove him to the hospital and carried suitcases with wigs up the stairs, because he was too weak. After a while the hospital provided a room in the basement as a salon for cancer victims. Over time, EBZ has helped more than 5000 cancer patients. There are now five active centers in several hospitals that provide wigs for cancer patients regardless of age, sex, religion or ethnicity.

Compassion can be elicited by increasing social awareness and evoking distress in others. SEs made extensive use of their own suffering to identify the opportunity to help others. They raised social awareness by sharing their personal suffering and involving key social actors and opinion.

leaders, through various communication channels. Their actions bridged self-compassion and collective compassion toward others, demonstrating that compassion has a contagious effect.

Self-Compassion Based on Imprinting Through Empathy

Five SEs discovered new opportunities through an imprinting mechanism, that is, opportunities embedded within the social, political and economic environment (for illustrative quotes, see Table A2A). All had experienced suffering in the past. These SEs who discovered opportunities did not emphasize their own suffering as being directly linked to the social opportunity. Rather, their personal suffering was a kind of trigger for social awareness to other’s suffering and to helping them. They were searching after well recognized opportunities, developing different approaches to alleviate the suffering of others.

AH started a venture to help young Ethiopian college graduates find jobs by empowering them, enhancing their leadership capabilities and enriching their social embeddedness within Israeli society (for more details, see Appendix 1A).Footnote 3AH’s story includes two layers of suffering: her childhood, when her parents divorced, and she felt she had no family; and her identity crisis and culture shock when she left the kibbutz she had lived on most of her life. Life in the kibbutz was like living in a big family, which she felt paralleled living in the Ethiopian community, even though she herself was not Ethiopian. She felt a sense of empathy with Ethiopians. Her narrative demonstrates how personal suffering led her to look for a community she could help.

AH and her co-founder identified the Ethiopian community through a deliberate search and focused on graduates who faced a glass ceiling. “There are about 70 social ventures that try to assist this community. Most provide ‘fish,’ such as scholarships and food; very few provide fishing rods,” she said. Though the two were creative in the way they mentored the young Ethiopian graduates, the opportunity was discovered through objectivity rather than personal suffering. AH made a connection between her own past experiences and being prosocially active, but the opportunity was identified within the social context—other people could just as easily have identified the same social opportunity had they tried. Thus, the OR was based on an imprinting mechanism.

Both RS and DZ identified opportunities connected to personal suffering in the past. Their underlying motivation was to prevent others from suffering. Although RS and DZ were motivated by self-compassion and an intimate understanding of how to resolve suffering, the prosocial action they took was embedded within the social context. They identified solutions employed by other SEs and developed new innovative approaches. YLE, who ran a soup kitchen, described being too poor to have meat in his childhood. It affected him emotionally and he did not wanted children to experience hunger. “There are many poor and hungry people, elderly, disabled, single mothers and children… who experience what I went through as a child…. I can’t fix it altogether, but I can try to minimize it.”

AR runs a social venture for divorced men and, transformed his own suffering into action. AR said, “It was started when I went through a divorce and discovered that reality is different from what I thought…. I had an idea to build an Internet site to provide information for those who went through the same experience…. It became my therapy.” AR identified an opportunity within the existing social structure and developed a new approach to helping divorced men. Both entrepreneurs (YLE, AR) indicated that their suffering in the past informed them about how to alleviate the suffering of others. At the same time, it provided them a way to heal their own helplessness in the past.

Other-Regarding Compassion

Twelve SEs indicated that their compassion was focused outwards. All identified that compassion derives from noticing another person’s suffering, feeling empathic concern and responding to their suffering. Other-regarding compassion was triggered by a social awareness, value structures and a sense of calling that led to prosocial action. Of the 12 SEs, half identified opportunities through reflexive processes based on sensemaking through innovation and half on imprinting mechanisms based on sensemaking of adaptation. Details for SEs’ compassion and OR in this category appear in Table 4.

As an example of sudden awareness, EA (animal rights activist) described having seen a television program about 30 years earlier that showed how dogs were shot to death by an organization that supposedly protected them. “I decided that instant to become active in protecting animal rights.” Similarly, ES, whose venture helps people in need, described the trigger for her prosocial action: “One day a woman knocked on my door. She was sent by my husband’s friend, who asked us to help her.” This request for help triggered a heightened awareness for ES and, combined with her values, motivated her to alleviate the suffering of others.

Social awareness developed over time for several SEs. After finishing her dissertation on poorly functioning mothers, HZ, whose venture assists abused children, felt a social responsibility to help such children. Her decision to take prosocial action was part of a process: “I wrote my dissertation on poorly functioning mothers. After getting my PhD, I felt I couldn’t abandon abused children…. There’s a need for vision, for stubbornness and patience…. My vision is that children will not be abused.”

RR, who provides shelter for battered women, described her process as noticing the connection between specific cases of abuse and identifying a need to create something to help many women: “A woman was murdered by her husband. He said he had no idea that his wife would die because she ‘was used to being beaten’… I was shocked and decided to establish a shelter for battered women.” This episode evoked a heighted awareness of violence against women and the lack of solutions to protect them. It made violence against women more salient for RR and she thought of developing an organization to help address the problem.

The understanding of other-regarding compassion was constructed retrospectively through strong sensemaking rather than a life story. As shown in Table B2B, the sensemaking narratives explain the SEs’ motivations: social responsibility as a desire to help and generate social solutions based on professional or personal capabilities, a strong sensitivity to social injustice, and a sense of calling to actively alleviate the suffering of others.

Other-Regarding Compassion Based on Reflexivity Through Innovation

Compassion here derives from addressing overlooked social problems and OR is associated with assigning a reflexive and subjective meaning to these social problems. The reflexivity is based on the interpretive reflections and the perceived emotional obligation to alleviate other people’s suffering, combined with an objective understanding of that suffering and the social solution needed. SEs attempt to alleviate suffering based on their social sensitivity and professional capabilities using innovative solutions of pro social problems they identified.

An elaborated example is presented by the case of RSL in Appendix 1B. RSL established a venture that focuses on birthday celebrations for children. Noticing that some children lacked the money to celebrate, she created a novel solution to this overlooked social problem. In hindsight, RSL felt that her compassion came from an experience she had at the age of 17, when a young girl she mentored could not celebrate her birthday. Her compassion toward others was based on social sensitivity. She drew a parallel between the importance of celebrating birthdays and building self-esteem to her own feelings of low self-esteem as a new immigrant who did not know the language. Her decision to become socially active evolved over time after many years of experience in the educational system: “It’s a process that grows like layers…a deep understanding based on layer upon layer, layers of awareness and consciousness.” RSL said that action was an important part of compassion; empathy was not enough. She demonstrated a strong sense of calling, of being socially responsible and needing to help others.

HZ’s social venture provides psychological support to children and adults who were sexually abused, and promotes awareness among children about sexual abuse. She had just finished her dissertation on sexual abuse among children when she decided to become an SE: “The only thing I can’t stand is children suffering.” When HZ solicited help from government agencies, she said that a typical response was: “You exaggerate, a Jewish mother would never hurt her children.… We had to establish the venture from below zero because we had to cope with denial.” HZ said that she would be abandoning the children if she did not do something to help them.

Similarly, YSH began supporting women who were sexually abused when she heard about a rabbi who abused a young woman. She felt compelled to help others. YSH established a wide forum to increase awareness about sexual abuse in religious communities and to provide support to women were sexually abused.

Other-Regarding Compassion and Imprinting Through Values

Imprinting mechanisms are based on identifying social opportunities within the social context. Six SEs identified a known social problem and developed varied approaches to solving the problem. Most SEs mentioned a sudden awareness of others’ suffering rather than a systematic search for social opportunities. Three of the six SEs (YL, ES and A) identified opportunities to alleviate other’s suffering based on ingrained religious values. For instance, YL decided to help people with medical and legal expenses (for elaboration, see Appendix 1B). In some ways, his concern for the suffering of others represents an associated value-based calling. His motivation is rooted in Orthodox Judaism, which is a calling for him: “You can alleviate suffering by listening to a person. It also has a side effect because a person is also listening to himself. After that you can try to think about solutions.” YL designed new ways to address the problem using multiple accounts to raise funds for people who needed expensive treatments. In addition, he successfully evoked collective compassion by asking people and organizations to donate unused medication.

ES and her husband, whose venture helps people in need, became SEs by chance. They, too, were motivated by religious values; helping others in need is a strong imperative in Judaism. ES referred to the sense of value-based calling: “You can call it a vision, a dream or a north star, it doesn’t make any difference…. If God sent me this mission to help people who need help, I should do it.”

In contrast, YV focused on children with disabilities. His mother worked in special education, providing him with deep insight and awareness. He thinks of children with disabilities as normal and wants to mainstream them and provide a wide range of support. He wants to grow his organization to serve every child in the country. He discovered the opportunity within the social context: disappointed with existing approaches, he looked for a new solution.

Three SEs indicated that their social awareness had its roots in their early childhood, modeled for them by their parents who were compassionate to vulnerable others and tried to help them personally. For example, Z, who ran a boarding school for children with disabilities, said, “I was raised in a compassionate atmosphere…the mantra was to contribute and help the poor…. My parents always had compassion and respect for vulnerable people.” A, who opened a support group for drug addicts, described the venture as “an intergenerational transfer of compassion.” EA, whose venture worked to protect animal rights, described it as acting to correct actions made by family members who were furriers and butchers. These SEs identified new opportunities base on their social awareness to others suffering.

In summary, OR and subsequent prosocial action can be reconceptualized by self- or other- related compassion. The process of OR can be reflexive or imprinting and possibly, a combination of both. Either way, the results are equifinal, both types of compassion and other process mechanisms can lead to OR.

Discussion and Theory Development

This study is one of the first empirical studies to empirically examine the sources accounting for the dynamic and varied nature of prosocial motivations. We sought to understand how SEs sensemaking of compassion-organizing processes led them to identify prosocial opportunities as well as which OR mechanisms were associated with the prosocial actions taken by SEs based on different types of compassion (Garud & Giuliani, 2013). Different types of compassion can lead to similar actions via different paths, helping explain how an SE’s affective and cognitive distress can trigger OR (Dutton et al., 2006). Compassion is one of the missing links within the sensemaking perspective that leads to action (Sandberg & Tsoukas, 2015, 2020). Our findings provide insights into why and how SEs are motivated to alleviate the suffering of others and the mechanisms through which they identified new prosocial opportunities. Table 5 summarizes the key findings and differences between the types of compassion.

Table 5 shows that both self- and other-regarding compassion use different sensemaking of compassion-based processes. These compassion-based processes can lead to the identification of prosocial actions via different mechanisms. As presented in Fig. 2, compassion is both a deep emotional and cognitive motivation that leads SEs to identify prosocial motivations via reflexivity and imprinting. Although these mechanisms are different in nature, overlaps can exist between different types of compassion and the mechanisms to identify prosocial OR. Similarly, there can be overlaps between the different OR mechanisms and prosocial action. Multiple combinations can lead to prosocial actions of either novel solutions or providing adaptive approaches to address well-known social problems. The different paths are equifinal, that is, they lead to prosocial OR and subsequent prosocial action.

Compassion and Prosocial OR

The process of compassion is multi-staged and is associated with different processes of compassion organizing. Observing the suffering of others appears to be related to human conditions that guide OR and are based on different sensemaking considerations. For self-compassionate SEs, compassion organizing is based on common humanity, mental distance and mindfulness. Self-compassion-organizing processes are associated with sensemaking of empathy, a deep understanding of what others are going through and knowing how to alleviate their suffering. OR and prosocial action can have a therapeutic effect on SEs. For other-regarding SEs, compassion organizing is based on noticing, feeling, and sympathetic sensemaking of helping others. Thus, SEs do not have identical experiences.

Our study enhances prosocial theory by showing that the prime motivation for SEs’ prosocial action is not rooted in self-interest or egoistic concerns (De Dreu et al., 2000). Rather, the motivations can be rooted in self- or other-regarding compassion processes and a desire to alleviate others’ suffering. In addition, our findings indicate that combining economic and social values as part of SEs thinking (Miller et al., 2012), is not essential when compassion serves as a prime motivation for identifying prosocial actions.

Self-Compassion and Prosocial OR

Self-compassion derives from personal suffering and reflects a desire to alleviate the suffering of others. It is sensemaking of knowing (Cunliffe & Scaratti, 2017). As presented in Appendix 1A, the organization of self-compassion is rooted in a process of seeing one’s suffering as part of common humanity and mindfulness. Past experiences trigger social awareness and prosocial OR. Our findings identify that SE’s recognized opportunities that could help them heal themselves with kindness and help those experiencing similar suffering.

SEs motivated by self-compassion are often committed to alleviate others’ suffering not as distant helpers, but as having something in common. When their personal suffering occurred in the present rather than in the past, SEs sought to alleviate their own distress with people in similar circumstances. Becoming an SE can be based on mental- and emotional-integrative thinking, managing internal distress resulting from his or her own suffering. These processes are recognized retrospectively by making sense of the prosocial actions SEs lead. These findings extend the theory on the connections between self-compassion and prosocial OR. They show that self-compassion processes are related to SEs sensemaking of prosocial OR and their own healing in the present or retrospectively (Neff, 2003a, 2003b a, b). By helping others, the SEs can also help themselves, decreasing self-pity and increasing well-being (MacBeth & Gumley, 2012). These findings are consistent with the idea that the less fortunate can help others in similar situations (Shepherd & Williams, 2014; Williams & Shepherd, 2016).

Most SEs driven by self-compassion identified new opportunities based on reflexivity from personal experience rather than a systematic search. Suddaby et al. (2015) describe reflexivity as a part of an entrepreneur’s subjective and interpretive inner world, where the entrepreneur can go beyond existing social, economic and political arrangements. Self-compassion is an affective process that can influence SEs’ cognitions and OR. SEs employ their prior knowledge and experiences based on empathy and a way of knowing, as a subjective reflection of alertness to and awareness of social needs. OR is based on representativeness and assumptions about similarities with others who are going through the same kind of suffering. By telling their own stories of suffering, SEs evoke social awareness, transferring their compassion from the individual level and to obtain social support from community members. These SEs draw on their own suffering to create social awareness and promote collective compassion. Some of the SEs identified that they felt powerless and that it took them several years until they were able to regain their power by pursuing social entrepreneurial activities. For example, one SE was only five years old when he witnessed his father’s extreme PTSD, which served as motivation to start a prosocial venture when he became an adult (please see Appendix 1A for further elaboration). Their OR and subsequent prosocial ventures enabled them to both obtain and provide social support, shifting from victim to healer, for themselves and for others (Atkins & Parker, 2012). In addition, our findings suggest that compassion can have a contagious effect, empowering others to act.

Some self-compassionate SEs discovered opportunities through imprinting mechanisms. The opportunities were “embedded in the social, political and economic context surrounding the entrepreneur” (Suddaby et al., 2015, p. 7). In some cases, SEs identified opportunities unrelated to their own suffering; however, their own suffering triggered social awareness of different needs. Cognitive processes are enhanced through an emotional lens and structural alignment between prior experiences of suffering. These understandings expand the literature on the role of entrepreneurial affect (Foo, 2011; Grichnika et al., 2010) in explaining entrepreneurial motivations and OR processes. Furthermore, it suggests that imprinting mechanisms are enhanced by subjective motivations, leading to different solutions for similar problems rather than replicating them (Marquis & Tilcsik, 2013).

Other-Regarding Compassion and Prosocial OR

Other-regarding compassion organizing relies on noticing, feeling and sensemaking (see Appendix 1B). SEs’ exposure to and noticing of the suffering of others evoked feelings of distress, sympathy and sensemaking of helping, using narratives as meaning (Dodge et al., 2005). In essence, the fortunate act to help the less fortunate. These SEs noticed others’ suffering based on social awareness that evolved over time and were based on value structures. Some SEs mentioned a trigger that evoked awareness of a social problem, something as simple as seeing a news story on television. Sometimes the vulnerable community’s needs were congruent with the SE’s professional capabilities and sense of calling (Hall & Chandler, 2005; Schabram & Maitlis, 2017).

Our findings support the notion that compassion for the suffering of others has both cognitive and affective aspects (Dutton et al., 2006; Kanov et al., 2004). Although affect leads to OR in self-compassion as well, the processes differ. Other-regarding SEs who noticed the suffering of others were able to develop a solution to a social problem based on social awareness and sensemaking of helping. They created innovative solutions to alleviate the suffering of others based on their understanding of the social problem as distant external actors. In that sense, other-regarding compassion leads to OR by leveraging others’ suffering to identify prosocial opportunities.

Unlike Suddaby et al. (2015), our findings show that other-regarding compassion can be associated with reflexivity based on social awareness, as SEs recognized overlooked opportunities and created new ones. Their subjective reflections stemmed from feelings about vulnerable others and understandings of the social problem and solutions. In most cases, their prior knowledge and professional capabilities served as a cognitive basis for developing a solution. Other-regarding compassion also led to OR based on imprinting mechanisms centered on value structures. Although opportunities were identified within the social context, only a few SEs indicated a systematic scanning of the environment (Alvarez & Barney, 2007; George et al., 2016; Hansen et al., 2011). When SEs noticed a social solution to a well-known problem that did not work well, they wanted to develop a new solution. Imprinting mechanisms may be associated with subjective reflections of SEs who use their feelings and cognition to address similar social problems differently (Marquis & Tilcsik, 2013).

Opportunity Recognition and Prosocial Behavior

We were able to identify different compassion-organizing processes and OR mechanisms that led to prosocial actions. They are organized differently and use different sensemaking processes. Self-compassion is reflected in subjective processes that lead to OR, which evolve from a desire to alleviate others’ suffering based on an intimate experience of suffering (knowing). Other-regarding compassion, in contrast, involves objective processes associated with an understanding of how to provide a solution to alleviate the suffering of others (helping).

Entrepreneurial motivations based on compassion serve as an internal enabler, as opposed to external circumstances that lead to an entrepreneurial opportunity (Davidsson, 2015; Davidsson et al., 2018). OR is based on subjective sensemaking processes that reflect perceptions over time (Garud & Giuliani, 2013; Korsgaard et al., 2016). Viewing the sources of OR as either cognitive (Ramoglou & Tsang, 2016) or subjective (Berglund & Korsgaard, 2017) may miss some of the nuances in the process of opportunity evolution and development. Compassion is a motivational construct based on a combination of emotional and cognitive drives to alleviate the suffering of others, rather than a result of instrumental rationality and cost–benefit” considerations (Bolino & Grant, 2016; De Dreu et al., 2000; Meglino & Korsgaard, 2006). Both affective and cognitive processes may result in the same action based on the mechanisms of reflexivity and imprinting, respectively (see Fig. 2). Thus, we extend the literature on OR processes.

Katz and Kahn (1978) characterize equifinality as reaching the same final state from different starting conditions and different developmental paths. Our findings show that paths between the different categories of compassion and OR are equifinal. Different processes may lead to the same OR via different mechanisms and a mix of cognitive and subjective processes. Compassion serves as an antecedent for prosocial OR, as it provides a logic of why and how SEs try to identify opportunities to alleviate the suffering of others. We add to the OR literature by identifying the equifinality of the different compassion sources and prosocial OR.

Directions for Future Research

This study employed the life-story method. Further inductive-based research can show how compassion and other affective-based motivations serve as internal rather than external enablers for prosocial OR (Davidsson et al., 2018) and the dynamics between different motivational constructs and their association with OR mechanisms. Future research may employ a longitudinal approach to examine if and how compassion-organizing processes change over time and how they might influence social ventures. Further investigation of an SE’s agency role and embeddedness within social-cognitive processes may help clarify entrepreneurial motivation (Grimes et al., 2013). Research is needed to clarify how the agency role of SEs is embedded at the macro level and within different social contexts. Moreover, it is important to examine how collective interactions within the community can lead to collective compassion and prosocial actions. For example, how does the contagious effect of compassion evolve from the individual to the community level over time and how does collective compassion reshape prosocial OR?

Compassion is not a prerequisite for all social ventures; prosocial action can be taken based on entrepreneurial identities (Mathias & Williams, 2018; Powell & Baker, 2014), knowledge and competence (Mair et al., 2012; Ramoglou & Tsang, 2016; Wry & York, 2017). Therefore, entrepreneurial identities are useful in explaining how for-profit entrepreneurs recognize and pursue new opportunities (Mathias & Williams, 2017; Powell & Baker, 2014). Future research could examine the interrelation between compassion, passion and entrepreneurial identities. Future research might examine relationships between compassion and identity among entrepreneurs who operate in commercial entrepreneurship, such as SMEs and high-tech. Alternate approaches, using deductive reasoning, testing the theories through hypotheses, observation, and confirmation/disconfirmation, can be used to solidify and build upon the foundational knowledge. Thus, a reasonable next step would be the development, validation and testing of more formal hypotheses.

As is the case in many studies, findings may be influenced by the cultures of the countries in which the research was conducted. Research in other countries and cultures can help enhance the generalizability of the study findings. In addition, when conducting new research, it would be useful to examine the regulatory structures of social entrepreneurs to determine its role in shaping the legal status of the ventures. Prosocial OR can occur in both commercial and social entrepreneurship. Our selection of participants in this study was deliberate. We selected small-scale SEs, as recommended by Shepherd (2015). It would be interesting to observe other categories of SEs, such as social constructionists and social engineers (see Zahra et al., 2009). In addition, it is important to study compassion and prosocial OR in the commercial sector.

By design, the focus of this paper was on prosocial OR rather than following the venture as it evolved. Examining the role of compassion and subsequent evolution of the venture would help provide a better understanding of the how prosocial process evolves, over time, in both social and commercial ventures.

Conclusions and Implications

In this study we developed a definition for SE OR, A social entrepreneur’s opportunity recognition, whether discovered or created, involves the identification of unmet social needs, with the goal of developing an innovative solution to create social value in order to fulfill those unmet needs. We empirically examined the role of compassion in understanding OR among SEs, showing how sensemaking and compassion lead to prosocial activities, analyzing both their social and cognitive processes. Thus, sensemaking theory provides important insight regarding how individual SEs identify, justify, and are motivated to engage in the prosocial arena. We also show that compassion has different roots that lead to prosocial OR. They are equifinal; that is, both self-compassion and other-regarding compassion lead to prosocial OR using similar mechanisms.

Our study findings extend existing theory regarding how different paths of compassion lead to OR and prosocial actions. In doing so, we make important theoretical contributions to understanding the role of compassion in shaping prosocial OR. The theory we developed sets up a platform for further research on the role of compassion in identifying and leading prosocial actions.

Public policy actors and scholars are increasingly looking for new models of organization that ameliorate some of the negative impacts of global inequality (Piketty, 2013). Environmental challenges and social dislocation call for new models of economic and social distribution that eclipse the binary socialism versus capitalism divide (Hall et al., 2013). The neoliberal paradigm is based on decision making directed by profit maximization, a collective aggregation of individual self-interest. Self-interest has served as a foundation for entrepreneurship scholarship, extensively studied from a range of social-psychological angles. This study demonstrates that various other altruistic motivations can play an important role in OR, and we believe these may lead toward effective and efficient solutions for many of the ‘wicked problems’ we face today. As we write this, the global COVID-19 pandemic is upending many previously unassailable conventions, including guaranteed income, public health systems, and world governance. Understanding and supporting SEs and their motivations will be critical to unpacking many of these seemingly intractable problems. Indeed, many alternative solutions of a post-neo-liberal model may be derived from, or currently practiced by SEs whose fundamental assumptions include strong ethical values developed through processes that we help unpack in this research. It is our hope that this scholarship leads to ingenious solutions to some of the wicked problems many of us face.

Notes