Abstract

This article examines why and how workers adhere and contribute to the perpetuation of the freedom fantasy induced by neoliberal ideology. We turn to Hannah Arendt’s analysis of the human condition, which offers invaluable insights into the mechanisms that foster the erosion of human freedom in the workplace. Embracing an Arendtian lens, we demonstrate that individuals become entrapped in a libertarian fantasy—a condition enacted by the replacement of the freedom to act by the freedom to perform. The latter embodies the survivalist modus operandi of animal laborans (1) who renounces singularity, by focusing on the function of supervised labor, (2) who renounces solidarity, by focusing on individualist and competitive labor, and (3) who is deprived of spontaneity, by focusing on the measured productivity of labor. Therefore, we propose a new corporate governance perspective based on the rehabilitation of political action in organizations as the best way to preserve human capacity for singularity, solidarity, and spontaneity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Corporations are getting better and better at seducing us into thinking the way they think—of profits as the telos and responsibility as something to be enshrined in symbol and evaded in reality. Cleverness as opposed to wisdom. Wanting and having instead of thinking and making. We cannot stop it. I suspect what’ll happen is that there will be some sort of disaster—depression, hyperinflation—and then it’ll be showtime: We’ll either wake up and retake our freedom or we’ll fall apart utterly. Like Rome—conqueror of its own people… We are not dead but asleep, dreaming of ourselves (David Foster Wallace, The Pale King).

Autonomy and individual responsibility are two hypernorms that characterize social reality in the age when alternative ethical orientations appear to have lost their universal appeal (Lyotard 1979). They also represent the main tenets of neoliberalism—a political-economic theory developed from inquiries into the question of individual freedom and its implications for political undertakings that seek to advance human well-being (Fine & Saad-Filho 2017; Harvey, 2005). The hypernorms of neoliberalism, discussed in this article, constitute a free market ideology that connects human freedom to the actions of rational, self-interested actors in a competitive marketplace (Jones 2012) and bestows upon individuals a social order based on specific principles of managing and organizing (Foucault 2008; Glynos 2008). The neoliberal ideas that slowly developed in Europe and in US academic circles during the postwar years capitalized on opportunities created by the social and economic storms of the 1970s. These ideas enabled a political shift towards an unlimited faith in the individual and in free market enterprise as deliverers of freedom (Friedman 1992). Regardless of what signifier is used—American corporate capitalism (George 2014), corporatism (Suarez-Villa 2012), or managerialism (Alvesson and Spicer 2016; Clegg 2014), neoliberalism has morphed into a new metanarrative that “penetrated common-sense understandings” (Harvey 2005, p. 41) and is widely perceived as the “natural state of affairs” in most Western democracies (Bal and Dóci 2018, p. 538).

Glynos and Howarth (2007) noted that individual freedom was the fundamental value at the heart of neoliberal thought, with a freedom imperative being its core characteristic. Paradoxically, various studies on managerialism have demonstrated that the freedom fixation of neoliberalism has in fact created multiple obstacles to individual liberties (Alvesson & Spicer 2016; Bal and Dóci 2018). Market-based reforms that eliminated labor protection and collective bargaining power—euphemistically labeled “the creation of flexible labor markets” (Jones 2012, p. 330)—were intended to produce greater social outcomes by unleashing the power of human initiative and providing autonomy for decision making. The founding fathers of neoliberalism—Hayek (1994) and Friedman (1992)—argued that markets were better than other forms of social organization in prompting human motivation (i.e., via self-interest and the individual pursuit of happiness) and that economic freedom was a sine qua non for political freedom. However, contrary to those expectations, and amidst one of the worst sanitary crises in recent history, we have learnt that unbounded glorification of self-interest may have a very opposite effect—inability to act collectively, institutional paralysis and distrust of the authorities. It has become evident that the responsibility for the self often times fails to translate into responsibility for the others.

We have also learnt that laissez-faire-driven forms of organizing economic activities lead to multiplication of practices of oppression at work disguised as efficiency management that deprives workers of their ability to have a voice and to matter in their organizations, even when their lives are put at risk.Footnote 1 Furthermore, the normalization of precarious work practices epitomized by the gig economy and celebrated as another pinnacle of freedom (Slee 2017) has revealed yet another dark side of neoliberal empowerment. While the gig economy remains unregulated, it is being broadly adopted by actors in contexts characterized by acute desperation for employment opportunities. This, in turn, allowed certain companies to leverage a stable labor supply from populations experiencing economic hardship (Ahsan 2018). Combined, these factors have led to a retreat to former, outdated labor arrangements such as zero-hour contracts (Fleming 2017) that compromise workers’ rights and well-being (Gandini 2019).

This paradox of disempowering freedom has been neatly summarized by Zygmunt Bauman: “Never have we been so free. Never have we felt so powerless.”Footnote 2 How can an ideology that places such a high normative value on individual freedom as a vehicle for prosperity also take much of the blame for a sense of increasing powerlessness? Further, and attending to insights offered by Bal and Dóci (2018), why are individuals subjugated by the pervasive dictums of market enterprise—instrumentality, individualism, and competition—unable to escape a fantasy world where precarity-breeding laissez-faire capitalism is the only safeguard of freedom?

It may be that most individuals renounce behaving as political actors or moral agents in their organizations unable or unwilling to escape the hypernorms of autonomy and individual responsibility heralded as the freedom of choice.

To better understand the triggers and consequences of individual withdrawal from political action in organizations, we draw on the work of Hannah Arendt and, more particularly, on the Arendtian notion of freedom in order to initiate a discussion on the differences between the freedom fantasy and real freedom. We introduce an ontological juxtapositioning of the freedom to act (i.e., real freedom) and the freedom to perform (i.e., the freedom fantasy) as an instrumental lever in invigorating this debate.

Hannah Arendt (14 October 1906–4 December 1975) was a German-American philosopher and political theorist whose main works are The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) and The Human Condition (1958). She also wrote an essay What is freedom? (1961) in which she clarifies her understanding of freedom not as an intellectual or voluntary choice but as an ability to act. Arendt is well-placed to inform the debate on freedom at work since her analysis of the human condition—as a realization of the self—offers a critical reassessment of the tumultuous relationship between individual freedom and organizational ideology and scrutinizes the illusory promises of self-actualization that are generated by modern production–consumption society. Therefore, contemplating the meaning of freedom in Arendtian terms helps uncover how workers can become entrapped in the freedom fantasy and offers clues how they can regain a path to freedom at work. Somewhat surprisingly, despite being one of the most prominent commentators on the ethical dilemmas and contradictions of modernity, Arendt’s writings have been rarely used in business ethics studies (Henning 2011). One recent exception is Gardiner’s (2017) study—“Ethical responsibility—An Arendtian turn”—addresses how Arendt’s corpus can provide conceptual depth to current discussions on responsible leadership. We take an alternate stance, building on Arendt’s conception of freedom and her explicit objection to accept consumer society served by free market enterprise as the ultimate epitome of human liberation.

Our study contributes to a literature that examines the impact of neoliberalism on the organization of work in a consumer society. We argue that an Arendtian perspective on individual freedom and the conditions for its actualization is helpful in explaining a paradoxical freedom fantasy that permeates life in organizations. Arendt’s analysis of the human condition offers invaluable insights on the mechanisms that foster the erosion of genuine freedom amidst an accelerating marketization of society. Deprived of their capacity for singularity, solidarity, and spontaneity, individuals are reduced to animals laborans, ensnared in an endless cycle of production and consumption—no longer capable “to live in the world” (Arendt 1958, p. 134). As a result, the freedom to act is replaced by the freedom to perform, and the latter is nothing more than bare compliance to an ideological regime that ordains the deployment of human energies in the production of materials necessary for the pursuit of consumers’ superfluities of life. To this end, our study proposes a new corporate governance perspective based on a political conception of freedom and a turn towards workplace democracy that could free workers from social, economic, and organizational pressure by creating conditions for singular, solidary, and spontaneous actions.

The article is structured in five sections. The first presents the literature on neoliberalism as an ideology and focuses on the nature of the freedom fantasy. The second specifies why the Arendtian vision—which provides a comprehensive distinction between the freedom to perform and the freedom to act—is relevant when addressing the freedom fantasy in organizations. The third explains how individuals participate in the ideological production of the freedom fantasy at work. The fourth discusses available avenues for cultivating the freedom to act in organizations. The final section identifies ethical implications and areas for future research.

Criticisms of Neoliberalism as Ideology: The Paradox of Disempowering Freedom

Neoliberal ideology views individuals as rational, economic agents acting out of self-interest (George 2014) and claims to offer them new freedoms to satisfy their interests and pursuits. To this end, a neoliberal ideology promotes market freedom and defends it from interventionist and regulating states, paternalistic forms of organizing, and oppressive collectives. A minimalist functioning of the state is maintained but limited to ensure individual freedom of choice (Harvey 2005). Neoliberalism proposes that “human well-being can be advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by strong property rights, free markets, and free trade” (Harvey 2005: 2). The freedom fantasy exists not only because individual freedom is the strongest value of neoliberal thought but also because neoliberalism is positioned as freedom’s exclusive guardian, thereby suggesting that it offers a better vision for humanity. A neoliberal order sets freedom as an object of desire and glorification. As such, neoliberalism is granted a normative carte blanche and an alluring moral superiority when justifying how liberty is pursued and how suffering and deprivation—often accompanying such endeavors—is exonerated.

Bal and Dóci (2018, p. 541) argued that “through this fantasy, neoliberalism grips the individual, and makes individualization, competition and instrumentality seem appealing and desirable as it offers freedom to the people.” This assertion raises three important principles. First, neoliberalism is an individualistic ideology in which every individual is assumed and expected to be self-interested and pursuing individual desires (Harvey 2005). Second, just as organizations should focus on attaining a competitive advantage, workers should strive to become more employable and more desirable in the labor market, obtaining the best jobs and careers (Lazzarato 2009). Workers’ presumed freedom is tied to one central condition: they must be successful – that is, “make” something of themselves. Third, labor and people in organizations are instrumentalized to generate profitability. This corresponds to “responsible autonomy” in the workplace enacted in the name of a company’s best interests rather than those associated with classes or unions (Fleming 2017). Workers see themselves as atomized instruments serving organizations that are focused on profit and shareholder value maximization (Friedman 1992).

A vision of freedom as autonomy—premised on absolute freedom of conscience for isolated individuals—favors the “commodification of everything” (Harvey 2005, p. 165). This type of commodification includes goods, services, and labor and promotes the development of a meritocracy—a free market that ensures a reward for hard-working individuals. Such a vision reduces labor and work to simple transactions between two parties who are focused on parallel pursuits and ignores the complex interdependencies of collective existence (Polanyi 2001). Thus, human freedom dissolves into a contractual, market freedom, which further “degenerates into a mere advocacy of free enterprise” (Polanyi 2001, p. 265).

On the one hand, workers gain freedoms, such as choosing their employers, negotiating for themselves, organizing their time, and managing and designing their career, and development at work (Harvey 2005). On the other hand, they also lose freedoms, such as choosing the purpose of their work activities and attributing meaning to their work (Bailey et al. 2016; Lips-Wiersma and Morris 2009). Constant evaluations at work cause a decline in self-determination and a growing dependence on external, often shifting, norms. This results in what the sociologist Richard Sennett has aptly described as the “infantilisation of the workers” (2003, p. 102). Workers display childish outbursts of temper and are jealous about trivialities, engage in ostensible shows of meaningless productivity, tell white lies, resort to deceit, delight in the downfall of others, and cherish petty feelings of revenge. According to Sennett, this is the consequence of a system that prevents individuals from thinking independently and that fails to treat workers as adults. Multinational corporations may act as “private governments” controlling not only the work lives but also the private lives of workers with increasing, totalizing intensity (Block and Somers 2014; Anderson 2017). Despite insistent advocacy for individual freedom, neoliberal ideology may, in fact, constitute a fully launched attack on workers’ ability to experience it. Scholars have offered varying reasons for the emergence of this paradox of disempowering freedom (Alvesson and Robertson 2006; Alvesson and Spicer 2016; Gleadle et al. 2008). We group these contributions into three categories that reflect multiple perspectives concerning what we call the “re-ideologization of the self” in the milieu of work and labor.

Self as an Entrepreneurial Subject

Modern day workers are expected and encouraged to engage in the development of entrepreneurial capabilities that allegedly augment their agency and expand their freedom of choice. Žižek (1989) noted that this freedom is illusory since individuals engaged in a neoliberal ideology are not free but rather constrained to a specific choice—being their own entrepreneurs. Foucault (2008, p. 119) described how neoliberal regimes of governmentality use an “economic approach to human behavior” not only as a descriptor of human conduct but also as a prescriptive tool to prompt subjects to act as competitive entrepreneurs. If individuals do not fit the mold of enterprising selves (Fleming 2014, 2017; Gleadle et al. 2008), they risk unemployment or precarious work (Bauman et al. 2015). Even in this case, neoliberalism considers a temporarily unemployed person an entrepreneurial “worker in transit” (Foucault 2008, p. 139)—an attitude that has become particularly visible in today’s proliferating gig economy. Unemployment has been recast as the consequence of mistaken investment choices that require re-education (Lazzarato 2009). To this end, an entrepreneurial subject can also be created through an educational system that prioritizes neoliberal values—such as self-investment, and professional success—and that avoids any pedagogical differentiation. Young people are encouraged to focus on the prestigious occupational choices that ensure career advancement regardless of their personal aspirations, extracurricular skills, interests, and values (Bourdieu 1996; Verhaeghe 2012). This requirement for success is based on an unconscious desire for omnipotence that can be easily confused with a desire for freedom. Facing social pressure to succeed professionally at all costs, a large proportion of workers can develop a fear of failure. This fear induces them to invest even more energy in work and to assimilate with a performance-driven culture in order to meet employer expectations.

In other words, failure is recast as a matter of individual responsibility. As Bal and Dóci (2018, p. 541) observed, “if the individual fails to succeed, it is their personal failure.” Thus, we argue that neoliberalism not only creates distance from a freedom of self-determination—acquired through actions of economic repudiation—but also embraces an oriented freedom associated with the cult of professional success.

Self as a Game Player

While becoming hyperflexible and offering workers the freedom of flexible labor relations and elastic time arrangements (Alvesson and Spicer 2016), organizations have adopted norms of objective comparison (i.e., quantitative measures to compare workers’ performance and exercise control over it). The resulting managerialism has not only increased the monitoring of workers’ daily activities but also reduced their freedom of practice (Alvesson and Spicer 2016; Anderson 2017; Larson 2018). Using Simone Weil’s (1933) conception of oppression, Grey (1996) has shown that performance management may be not only oppressive but also futile and self-defeating for workers.

Historically, performance management has been linked to the scientificization of work, the objectification of evaluation criteria, and the development of coercive forms of power (e.g., rewards and punishment). Such areas of inquiry have been explored in consulting, accounting firms and business schools, revealing an excessive focus on technical accuracy, technical neutrality, and technical abstraction (Alvesson and Robertson 2006; Malsch and Guénin-Paracini 2013; Frémeaux et al. 2020a, b), and an excessive focus for academics on publication opportunities and elegant publishable models (Alvesson and Spicer 2016; Edwards and Roy 2017; Frémeaux et al. 2020a, b). Continuously monitored and evaluated individuals feel compelled to adopt desired behaviors and to submit to the type of soft domination found in contemporary organizations. Indeed, control resides in insidious techniques that influence how workers conceptualize professional achievements and that neutralize public manifestations of disagreement with imposed criteria of self-worth. The control of everyone by everyone leads workers to lose their autonomy and to become co-opted by a process. Gabriel (2005) uses the metaphors of a glass cage and a glass palace to illuminate how hyper-transparent organizations exhibit both uninterrupted visibility and constant surveillance. Examining the work of researchers in business schools, Alvesson and Spicer (2016) show that academics reconcile a loss of professional autonomy by treating work as a game and seeing themselves as players rather than researchers. Given the economic pressure to evaluate workers exclusively on their visible outcomes, most of them focus on the objective and quantifiable reality of the work. Therefore, freedom of flexibility granted in organizations emerges as a controlled freedom.

Self as a Responsibility Taker

Workers have also been forced to take on new responsibilities in exchange for granted freedoms of flexible labor (Alvesson and Spicer 2016). Contemporary organizations use a manipulative process to grant workers more flexibility—flattering them as responsible and committed contributors—in exchange for the obligation to give even more in return. The granting of freedoms is no longer a tangible sign of concern for the well-being of workers but rather a reflection of the company’s defense of an economic imperative. In exchange for a measure of autonomy, workers are invited to be more committed, to accept even more responsibility, and to adopt a positive discourse on organizational functioning. A totalizing and formal discourse—outlining delegation, empowerment, and commitment—favors a shift of responsibility to workers, which simply reflects the recurrent expectations expressed by them. Moral guilt is mobilized to justify governmentality and hammer it into the consciousness (Micali 2010). Individuals criticize their own inability to work competitively instead of the politics that made them compete in the first place (Lazzarato 2015). Subjected to organizational pressure that pushes them to take on new responsibilities, workers not only lose their ability to think critically but also relinquish their power to act from another perspective beyond careerism induced by managerialism.

If this totalizing discourse is combined with a lack of transcendental purpose, workers risk facing greater responsibilities amidst boundary deprivation, which creates the perception that they are the only ones responsible for managerialism. The freedom advocated by a neoliberal ideology is thus a freedom responsibility, whereby workers not only gain new spaces for freedom but also assume responsibilities dictated by others.

The problematic implications of the re-ideologization of the self—and associated implications for our understanding of the nature of freedom—were first raised and acknowledged by Arendt in The Human Condition (1958). In her discussion of a consumer society, Arendt pointed out that while the emancipation of labor for higher productivity had meant progress towards non-violence, “it [was] much less certain that it was also progress in direction of freedom.... [L]abor may have become the occupation of free classes, but only to bring to them the obligation of the servile classes” (Arendt 1958, p. 130). This unsettling observation prompts the question of why individuals adhere to an ideology that impedes their freedom. Given the typical working conditions under twenty-first century capitalism, the notion of freedom in contemporary organizations must be reexamined in ways that can accommodate “the interrelations between power, domination, [and] freedom” (Visser 2019: 2). We contend that Arendt’s writings on ideology and the human condition offer a promising avenue for such re-examination by unveiling an important distinction between the freedom to act and the freedom to perform—two fundamentally different realities in organizations.

The Freedom to Act Versus the Freedom to Perform

Prompted by intellectual debates following World War II, Arendt sought to apprehend the intricacies of the human condition: “How can individually moral human beings produce collective immorality?” (see Reinhold Niebuhr’s 1932 book, Moral Man and Immoral Society). For Arendt, the answer could be found by revisiting the nature of human action in existential and political terms and by philosophically distinguishing human action from other types of activities. Freedom—sets as the ability to act and reveal oneself to others—occupies a central position in this distinction and heralds the moral significance of human activity in the public realm. In The Human Condition (1958), Arendt contended that the human condition is constituted by three fundamental activities: labor, work, and action.

The biological necessities of the human species—sustenance and reproduction—are satisfied through labor, which is characterized by cyclicality and repetitiveness. Arendt reignited the notion of animal laborans, shifting it from a lonely laborer trapped in a tedious cycle of elemental tasks for survival to a submissive actor engaged in a dynamic cycle of creation and destruction amidst materialistic abundance.

As conceived by Arendt, work provided an artificial world “distinctly different from all natural surroundings” (Arendt 1958, p. 7). These activities created “the world” and—in one way or another—set it against “the earth.” Work processes were linear and involved an extraction and a subsequent transformation of natural matter into an object that could be used, evaluated, and exchanged. Its “realisateur” was homo faber, a fabricator of durable human goods. Arendt’s conceptual separation of labor and work has important implications for our understanding of freedom in organizations: it reflects the varying degrees of agency that are available to individuals within the organizational realm. While both labor and work were generative and transformative, homo faber possessed a creative power that animal laborans lacked—the freedom to create durable goods that are intended to meet genuine needs and to build the human artifice can be shared with others. Thus, with the term work, Arendt also designated individual’s socialization and personality development in daily life through cultural and social relations, economic interests and consumption. Work as an activity, according to Arendt, created necessity for cooperation because production–consumption system had augmented the degree of human interdependence, but the principles of this cooperation were not egalitarian as they were determined by social roles of individuals and their material conditions. Furthermore, Arendt (1958, p. 126) observed that gradually this artificial order of organizing and accelerated social exchanges had led to the replacement of the values of work with the values of labor:

In our need for more and more rapid replacement of the worldly things around us, we can no longer afford to use them, to respect and preserve their inherent durability; we must consume, devour, as it were, our houses and furniture and cars as though they were the “good things” of nature which spoil uselessly if they are not drawn swiftly into the never-ending cycle of man’s metabolism with nature.... The ideals of homo faber, the fabricator of the world, which are permanence, stability, and durability, have been sacrificed to abundance, the ideal of the animal laborans. We live in a laborers’ society because only laboring, with its inherent fertility, is likely to bring about abundance; and we have changed work into laboring, broken it up into its minute particles until it has lent itself to division where the common denominator of the simplest performance is reached in order to eliminate from the path of human labor power—which is part of nature and perhaps even the most powerful of all natural forces—the obstacle of the “unnatural” and purely worldly stability of the human artifice.

For Arendt (1958, p. 217), the chief difference between slave labor and modern ‘free’ labor was not that the modern laborer possessed personal freedoms—freedom of movement, economic activity, and personal inviolability (although we increasingly see these aspects declining under an advancing technological control of work)—but rather that “he is admitted to the political realm and fully emancipated as citizen.” Such admittance, therefore, signified an ability to act and appear as oneself. When deprived of this possibility, the modern laborer was stripped of all forms of political recognition and instrumentalized to serve the system’s reproduction needs.

Thus, Arendt (1958, p. 7) positioned action as the final, fundamental human activity necessary for the liberation of animal laborans:

Action, the only activity that goes on directly between men without the intermediary of things or matter, corresponds to the human condition of plurality, to the fact that men, not Man, live on the earth and inhabit the world. While all aspects of the human condition are somehow related to politics, this plurality is specifically the condition—not only the conditio sine qua non, but the conditio per quam—of all political life.

According to Arendt, the twofold character of the human condition of plurality simultaneously encompassed equality and distinction, which allowed space for the exercise of freedom through action and speech. Equality stemmed from not only belonging to the same species but also inhabiting a common world and realizing a common understanding. We are equal because we are conscious beings by way of our ability to feel, suffer, and think—qualities that enable us to develop our capacity for empathy and moral imagination.

Yet humans are also distinct due to unique histories and unique world perspectives. Differences reside in individual efforts of self-transcendence and self-manifestation, and in impulses of disclosing who we are to the world. We may feel distinct, but we achieve distinction through action and speech in the presence of others. According to Arendt (1958, p. 179),

In acting and speaking, men show who they are, reveal actively their unique personal identities and thus make their appearance in the human world, while their physical identities appear without any activity of their own in the unique shape of the body and sound of the voice. This disclosure of “who” in contradistinction to “what” somebody is—his qualities, gifts, talents, and shortcomings, which he might display or hide—is implicit in everything somebody says or does.

Arendt highlighted a fundamental aspect of the disclosure of the ‘who’ that set action apart from all other human activities (i.e., an agent has no control over how his/her action appears to the recipients of that action). The disclosure of the ‘who’ was never a willful purpose: “On the contrary, it is more than likely the ‘who’, which appears so clearly and unmistakably to others, remains hidden from the person himself” (Arendt 1958, p. 9).

Arendt (1958, p. 180) also emphasized that the revelatory and unpremeditated character of action “[c]omes to the fore where people are with others and neither for nor against them—that is, in sheer human togetherness. Although nobody knows what he reveals when he discloses himself in deed or word, he must be willing to risk the disclosure, and this neither the doer of good works, who must be without self and preserve complete anonymity, nor the criminal, who must hide himself from others, can take upon themselves.”

Therefore, action that affirmed the “who” occurred only within the realm of human togetherness, where people appeared not as physical objects—possessors of human capital, aggregators of useful characteristics, or different makers of things—but as “qua men” (Arendt 1958, p. 176). Arendt highlighted the dangers that lay in substituting performing for acting. The concern with demonstrable profits and the obsession with smooth functioning and sociability has pushed organizations on a path of manufacturing consensus and consent (Herman & Chomsky 1988). When the action’s context is de-politicized—emptied of civic significance or demolished altogether—speech becomes mere talk and action transforms into dispirited making. The result is an imitation of politics and a simulacrum of freedom. Thus, Arendt compellingly demonstrated that any instrumentalization of action—an attempt to channel it towards a pre-determined end—reduces it to mere performance and curtails freedom by spurring men to retreat into “what” identities. In plain terms, performance management has replaced true freedom of action with its surrogate—the freedom fantasy, which curbs existential impulses of becoming.

For Arendt, to position freedom as an exercise in rational calculus was to neglect the very political quintessence of its emergence. One cannot know what it means to be or to feel free without enacting the human urge to distinguish oneself that accompanies us from birth. In “Freedom and politics: A lecture,” Arendt (1960) postulated that our sense of inner freedom is contingent upon experiencing. A sense of distinctiveness may be set as a condition for freedom, but it can only be affirmed through the ongoing exercise of political capacity through action and speech. The latter is indispensable for the democratic formation of opinion and will, and attainment of consensus on the part of equal and cooperating individuals. Thus, according to Arendt “[s]peech corresponds to the fact of distinctness and is the actualization of the human condition of plurality, that is, of living as a distinct and unique being among equals” (1958, p. 177).

In the milieu of organizing, the neoliberal idea that the empowerment of workers is nothing more than a conversion from animal laborans to homo faber (e.g., entrepreneurial subjects or responsibility takers) is yet another manifestation of the freedom fantasy. Such conversion does not liberate individuals from the imperative of participating in the relations of economic production under strictly defined terms of performance evaluation and utility (Micali 2010). Instead, true freedom of action is substituted with controllable freedom of performance—work is transformed into an unescapable form of oppression. The conditions for action—that is, the possibility to transcend the confines of prescribed organizational roles—are eliminated. Consequently, the lack of opportunity for transcendence makes freedom impossible (e.g., the difficulty to view workers in Foxconn factories or Amazon warehouses as ‘free’).

While managerialism seeks to restrain the space for human agency due to the irreversibility and unpredictability of action’s consequences, Arendt considered it a risk worth taking if humanity wished to avoid social stagnation and declining creative and moral powers. In societies that have embraced managerialism, many commercial activities are hindered. For example, in the space of a few years, the UK has seen “a relatively skilled (but unionized) workforce converted into an army of isolated agency workers and Deliveroo bicyclists delivering pizzas” (Fleming 2017, p. 693). A corporate culture of manufacturing consensus through performance management has played a part in “dumbing down” rather than in upskilling and emancipating organizations. Arendt would have viewed this outcome as unsurprising because when the freedom to act is replaced with the freedom to perform—work degenerates into ritualist compliance and reproduction of an organization’s authoritative norms. Therefore, the eventual outgrowth of performance maximization through freedom ordering is desolation. By renouncing the freedom to act and privileging the freedom to perform, animals laborans become entrapped in the dreary condition of modern day Sisyphus. We contend that the work of Arendt helps us understand how contemporary workers are drawn into this dynamic, becoming unwitting participants in the production and ossification of the freedom fantasy.

Ideological Production of the Freedom Fantasy

Arendt did not claim that workers were condemned to a totalitarian experience but rather insisted that a knowledge of totalitarianism could help them consciously bear the burden imposed by current events and to increase their awareness of new forms of totalitarianism. Arendt did not coin the term totalitarianism; it had already been in use since the 1920s by opponents of fascism, such as Paul Tillich (1934) and Herbert Marcuse (1968). However, in The Origins of Totalitarianism, Arendt (1951) proposed a political theorization of the phenomenon—totalitarianism was not a despotic or tyrannical regime characterized by the use of violence but rather a regime created by the failure of politics. Arendt (1951, p. 459) argued that “[t]oday, with populations and homelessness everywhere on the increase, masses of people are continuously rendered superfluous if we continue to think of our world in utilitarian terms. Political and economic events everywhere are in a silent conspiracy with totalitarian instruments devised for making men superfluous.”

Consequently, the notion of a totalitarian order is less of a form of political oppression and more of a form of political agony. Arendt pointed out that a totalitarian order derives its strength from the ideology to which it is attached and from gradual uniformization of thinking. Drawing on her analysis, we outline three main processes that underlie the praxis of a totalitarian ideology: the elimination of human singularity, the corruption of human solidarity, and the liquidation of action spontaneity.

The Elimination of Human Singularity

Totalitarianism is characterized by the development of homogeneous masses whose behaviors are stable and predictable. According to Arendt (1951, p. 308–311), “[t]otalitarian movements aim at and succeed in organizing masses... [of] neutral and politically indifferent people”, unlike classes united by a particular interest and pursuing common objectives. Further, Arendt noted that the support of totalitarianism was less a result of ignorance or propaganda and more a consequence of adherence to a totalitarian ideology. The development of homogeneous masses—whether it happens through algorithmization of activity or through organizational regimes of normativity—leads to the destruction of human diversity and flattening out of political debate so that rather than being based on plurality it becomes conformist and meaningless. As noted by Kohn (2002, p. 634), individuals have ceased to be human beings and have become a “mere mass of identical, interchangeable specimens of the animal-species man.”

Drawing a parallel with the modern world’s production–consumption society, we may observe that working activity may have been gradually reduced to a function of laboring. A production–consumption society erases the distinction between labor and work—labor absorbs work and becomes the central value of society and the only criterion of worthiness. Labor is positioned as the only serious activity of a society that exerts a social pressure based on the cult of career achievement and urges individuals to become entrepreneurial subjects (what we called oriented freedom)—a focus conducive to producing a homogeneous mass of workers who renounce their singularity, i.e., their ability to reveal their inimitable selves to others.

The Corruption of Human Solidarity

Freedom occurs in social interactions that generate solidarity and foster fruitful political exchanges. A shift to a totalitarian ideology destroys the space necessary for freedom, because social relations quickly degenerate into competitive individualism that disregards the value of solidarity and instigates distrust, isolation, and loneliness: “[A] tyranny over ‘laborers,’ however, as for instance the rule over slaves in antiquity, would automatically by a rule over lonely, not only isolated, men and tend to be totalitarian” (1951, p. 475). Lacking a space for action, resistance to a totalitarian ideology becomes either inconceivable or unutterable. Arendt (1951, pp. 466, 474) noted

By pressing men against each other, total terror destroys the space between them.... Totalitarian government does not just curtail liberties or abolish essential freedoms;... [it] destroys the one essential prerequisite of all freedom which is simply the capacity of motion which cannot exist without space.... Isolation and impotence, that is the fundamental inability to act at all, have always been characteristic of tyrannies.

In a production–consumption society, the performance imperative exerts an economic pressure based on the control of visible and objective tasks which forces workers to play the game of inter-individual competition (what we called controlled freedom) and deprives them of reciprocal relationships with others and the sense of shared world—the very condition of their freedom. The techniques normally associated with the neoliberalization of work such as the establishment of competition and performance evaluations repress empathy for the suffering of others—solidarity would hinder an individual’s own well-being in the organization. Thus, workers relinquish working together, with a growing indifference to the needs and grievances of others and confronting only their own selves. By removing the capacity for solidarity, neoliberal ideology produces uprooting. The uprooted self can no longer encounter a nurturing environment in the entrenchment of multiple communities such as family, business, and nation. Belonging to an uprooted mass, the individual finds herself in a state of estrangement from a community life that has typically transmitted solidarity from generation to generation. The price of uprootedness—created by the demolition of action space for nurturing solidarity—is loneliness, a predicament of Western society since the beginning of the industrial revolution (Anderson 2017).

The Liquidation of Action Spontaneity

As stated earlier, Arendt emphasized that natality creates the condition for action necessary to learn about and freely engage with the world through an interplay of unique and distinct experiences. One of the main characteristics of such action is its spontaneity that allows human beings to experience child-like discoveries and envision new possibilities. In other words, the capacity for spontaneity that emerges at birth imparts the unpredictable potential of existential creativity, which not only enriches but also transcends social order. According to Arendt (1951, p. 475):

[O]nly when the most elementary form of human creativity, which is the capacity to add something of one’s own to the common world, is destroyed, isolation becomes altogether unbearable. This can happen in the world whose chief values are dictated by labor, that is where all human activities have been transformed into laboring.

However, it is precisely this unpredictability that protects the individual from total domination: “For to destroy individuality is to destroy spontaneity, man’s power to begin something new out of his own resources, something that cannot be explained on the basis of reactions to environments and events.... [S]pontaneity as such, with its incalculability, is the greatest of all obstacles to total domination over man” (Arendt 1951, pp. 455–456).

In Arendt’s view, spontaneity was the ability to act in a non-ideological fashion, and it was, thus, the defining and quintessential expression of freedom. Neoliberalism has no space for spontaneity beyond a pre-programmed and commodified form. Therefore, spontaneity is a nightmare for neoliberal organizations precisely because it escapes the confines of manageability built around incentives and ideological reassurances.

Indeed, the performance imperative exerts an organizational pressure that forces workers to take responsibility and respond to constantly renewed targets (what we called freedom responsibility). Workers can be granted a choice in selecting the means to meet their productivity targets, but the conditions to question the very necessity of imposing and classifying targets for evaluative purposes are eliminated. In other words, all activities around performance imperative become de-politicized by being rendered undebatable. By focusing on the rhythms of work and forced into the game of relentless productivity, workers are deprived of the spontaneity of action and the creativity they need to live for themselves. They inhabit a negative spiral—free time is used to consume in excess, which encourages them to work in excess and take on ever new responsibilities of performance imposed by the system. By internalizing the responsibility for relentless performance, one is gradually forced to eliminate or avoid all spontaneous and non-prescribed forms of engagement in organizational life. This absolutism of productive imperative has become particularly noticeable with the switch to teleworking during the Covid-19 crisis—everything that does not directly improve or interferes with performance becomes a “distraction” or a nuisance (Hennekam and Shymko 2020).

In sum, animal laborans participates in the ideological production of the freedom fantasy by embracing the freedom to perform, which centers on career success, objective and quantifiable outcomes, and commitment to work. As such, animal laborans renounces the freedom to act, which germinates in singularity, solidarity, and spontaneity. Further on, we build a case for the indispensability of cultivating the freedom to act in organizations.

Cultivating the Freedom to Act in Organizations

The Arendtian perspective offers an original vision of corporate governance based on a political conception of human freedom as an ability to act within organizations. Indeed, Arendt dedicated a significant portion of her professional life defending the political realm against its ideological annihilation by totalitarian regimes. Until very recently, a de-politicized society has been positioned as a predicament of the state and a reflection of the weakening prestige of political institutions (Sennett 2003a, b). The domain of work and labor has been exempted from such a preoccupation; dominant neoclassical theories of the firm typically present production relations as free from the afflictions of power struggles and authority (Anderson 2017). The ontological simplicity of defining free market enterprise as a nexus of contracts and voluntary exchanges between various resource holders has effectively shielded it from democratic accountability. However, this has changed with the intensification of corporate involvement in public affairs that are indirectly associated with economic activities, and the popularization of stakeholder theory that has increased the visibility of normative obligations underlying production relations. The emergence of the corporate citizenship literature—built around the discussion of social responsibility of free market enterprise—challenged neoliberal views and created space for applying political theory to the reality of organizational life (Heath et al. 2010). For example, Knight and Johnson (2011) suggested that questions about the nature of corporate responsibility in the domain of civic virtues should not be positioned as moral questions. They were in fact necessarily political and required answers that explicitly addressed the implications of politics for such justifications. This shift in vision situated corporations in the center of the debate on the principles of corporate governance in democratic societies and prompted critically minded management scholars to build a case for corporate democracy (Edward and Willmott 2008a; Thompson 2005). Edward and Willmott (2008b, p. 405) notably argued for the democratization of corporations “insofar as these [political and economic] systems are institutionally resistant to... [tougher controls], it is necessary simultaneously to challenge and rebuild—that is, more fully democratize—political and economic systems” (see also Edward and Willmott 2008a). However, Edward and Willmott (2008a; 2008b) did not provide clear directions on how to reach a full democratization and what that might imply. Other studies that examined corporate governance through a political lens (Blanc 2016; Néron and Norman 2008; Norman 2015; Singer 2015) focused on a political conception of justice and, particularly, on John Rawls’s (1971) theory of justice to address this gap. However, the Rawlsian approach has proven to have its own limitations when applied to corporate governance. Singer (2015, p. 88) observed that “a political approach to business ethics and corporate governance requires an even more complicated and nuanced theoretical apparatus than the one Rawls has given us.” Our study is positioned in business ethics debates that favor the promotion of workplace democracy; however, it has the special feature of building on a political conception of human freedom.

When considering collective agents such as firms, the apprehension of their engagement in public affairs cannot be meaningfully built on the same principles as those applied to evaluate civic virtuousness of individual citizens (Néron and Norman 2008). What is needed is a focus on how corporate engagement with public affairs can be supported and legitimized by organizational culture of democratic accountability and participation. We propose that cultivating the freedom to act represents one significant step towards creating such culture. Specifically, the freedom to act is enabled by a mode of governance that does not extinguish political life but rather fertilizes it by simultaneously developing organizational capacities dedicated to (1) respecting human singularity, (2) nurturing solidarity as a condition for community emergence, and (3) safeguarding space for spontaneous action.

Limits and Scope of the Arendtian Perspective

Evoking both the origins and processes involved in the destruction of freedom, Arendt shows that ideological submission generates the weakening of our capacity for thinking and reveals how individuals can participate in a totalitarian ideology when deprived of the political conditions that support the free expression of singularity, solidarity, and spontaneity. In modern society—which elevates production and consumption to categorical imperatives, individuals run the risk of experiencing deprivation and being reduced to indistinguishable uniformity as laborers lacking moral sense. In organizations, workers reinforce a neoliberal order by recasting themselves as willing entrepreneurial subjects, deft game players, and eager performance responsibility takers. Here, labor is the morally significant and central concern of human existence. Accordingly, a worker’s feelings of self-worth are increasingly provided by activities that emphasize productivity, career building, and material success—often at the expense of other activities that emphasize the search for meaning, creativity, originality, and community building.

Although the freedom fantasy is built on the hope of resuscitating homo faber by granting laborers the freedom to perform, the Arendtian analysis demonstrates that—in the absence of political emancipation—such efforts push workers into yet another form of ideological submission, even in a new form of totalitarianism that further curtails the freedom to act. The key insight from Arendt’s analysis of human condition is that depoliticization of collective life creates fertile conditions for dehumanization of dignity that characterizes totalitarian order. In neoliberalism, such depoliticization occurs through the ideological dismissal of the notion of “shared world” (intrinsically linked to the idea of collective responsibility and interdependence) and the shift from the politics of building consensus to the politics of imposing consensus. If there is “no world to be shared,” undermining the political significance of recognizing plurality of perspectives becomes inevitable as social life degrades into producing winners and losers of competitive games and eliminating the necessity for dialog. As the sense of responsibility for the shared world vanishes from civic life, de-humanizing practices risk to become a tolerable reality paving the way for establishment of totalitarian authority. Thus, it may be that neoliberalism is a new form of totalitarianism not built through the usage of terror, but through the imposition of the worldview that defines all human relations through a lens of transactional logic rather than shared responsibility and cooperation. This connection between neoliberalism and totalitarianism has already been highlighted by several authors, in particular Vassort (2012), who considers that the logic of production–consumption is at the origin of a contemporary superfluity: subject to performance imperatives, people are confronted with a new form of totalitarianism that deprives them of possibility to critically interrogate the meaning of their work and prioritize non-productive aspects of it. Consequently, freedom to perform promoted by neoliberalism provides ground for totalitarian rule because it undermines human capacity to transcend the existing ideological order by confining the choice to act within the matrix of recognizable achievement and thus stripping action of its genuinely transformative force and political potentiality. We also understand better how neoliberalism has recently been imported into the political world to found governments that no longer draw their strength from political authority but from industrial ideology. As Pierre Musso (2019, p. 311) describes it, alongside managerialist leaders within organizations, we are witnessing the emergence of presidents–entrepreneurs within states who “offer the two-sided figure of the sovereign and the manager” and who in turn indulge in a managerialist leadership of populations based on this libertarian fantasy.

We show that Arendt’s work contributes to the business ethics literature by explaining how and why individuals abandon civic behavior and moral agency in the workplace. First, individuals renounce their singularity—and endorse the organizational notion of professional success—by taking a survival perspective in the function of laboring. Second, individuals renounce solidarity by prioritizing visible and objective achievement and succumbing to the imperative of hyper-competitiveness. Third, individuals are deprived of spontaneity by constantly monitoring the pace and quantity of their own labor and by taking on new responsibilities—thereby zealously participating in the production of expected results. Consequently, we offer an explanation for—and elucidate the link between—the pursuit of a libertarian fantasy and the proliferation of managerialist abuses, such as the erosion of working conditions, the degradation of workplace solidarity, and the fostering of the gap between institutional ideals and the reality of work (Alvesson and Spicer 2016; Anderson 2017; Bal and Dóci 2018; Clegg 2014). By yielding to professional and individual success and by positioning success as an essential manifestation of freedom, labor is objectified, and laborers are subsequently oppressed ideologically.

More specifically, we contribute to the literature on managerialism (Alvesson and Spicer 2016; Clegg 2014) by highlighting possible ways of combating the excessive objectification of work and the weakening of freedom to act. Indeed, Arendt’s approach reveals that respecting the freedom to act requires challenging the levers of performance, i.e., the social pressure to achieve career success, the economic pressure, which requires greater control over objective results, and the organizational pressure, which demands commitment and responsibility within the company. It may be that managers can only escape the torments of managerialism if they leave individuals free to experience what Gomez (2013) calls the subjective and collective dimensions of work and what we call, through our interpretation of Arendtian work—the singular, collective, and spontaneous dimensions of work activities. More practically, this implies that managers should pay attention (i) not only to career development but also to creating enabling conditions for versatile forms of workers’ fulfillment and flourishing in the professional context, (ii) not only to objective individual performance but also to the fruits of collective work, and (iii) not only to commitment to work but also to the suspension of working time allowing for creativity. For example, managers can be more explicit about how work activities contribute to common good and human development; they can provide opportunities for workers to do their work with care and creativity; they can set up incentive and reward systems that focus on collective achievements; they can be more flexible about prescribed work and welcome non-prescribed work based on spontaneity.

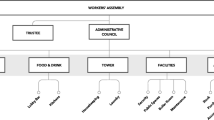

Table 1 synthetizes how a libertarian fantasy can develop within organizations, how according to Arendt, an ideology can impede freedom by preventing the expression of human singularity, solidarity, and spontaneity, and how the Arendtian reflection on freedom gives new insights on a corporate governance perspective.

Arendt’s clarification of a libertarian fantasy may come across as somewhat overly sophisticated because of her understanding of action and work. According to Arendt (1961), true freedom was not a phenomenon of inner will but a property of external action. Freedom was the ability to create the improbable through one’s intervention in the world and an antidote to “world alienation,” a situation in which great numbers of people, despite living and working in plain sight of each other, lose all sense of sharing a common world. As such, this very detailed and subtle analysis of action permits us to draw a line between acting and performing. The strength of the Arendtian perspective lies in the idea that we are free in acting and that, conversely, we lose our freedom in performing. In addition, Arendt’s vision of work reflects bold and original thinking. She was aware of the movement that glorified labor and led to the advent of animal laborans. However, she also refused to accept a society without work, and she opposed the idea that technological progress would be a source of freedom. As articulated in Honig (2001, p. 797), Arendt writes “[T]he law of progress holds that everything now must be better than what was before. Don’t you see, if you want something better, and better, and better, you lose the good. The good is no longer even being measured.” As such, the automation of tasks would aggravate the failings of a society organized around performing. Therefore, Arendt was adamantly opposed to conceiving work as the only noble activity of our existence. Rather, she invited us to rethink the value and meaning of work by rehabilitating political action. In sum, she provided the critical tools that may help de-ideologize a neoliberal discourse of freedom and unmasked it as a hoax.

The Arendtian vision of freedom may seem frustratingly difficult to experience. Individuals may be tempted to take refuge in activities where they are isolated from everyone and where they remain in control of their actions. However, Arendt led the way to true freedom by revealing—in a rather positive way—the power of acting with others. For example, by participating in discussion spaces that attend to varying ways of pursuing the common good through work activities, workers have the opportunity to experience and express singularity, solidarity, and spontaneity. The freedom to act within organizations does not create disorganization but rather instills the principle of morally and civically conscious acting, which allows workers to free themselves from an instrumental logic.

From this point of view, Arendt brings hope: human freedom is possible when political action is exercised. In other words, free action is the initiative of people who accomplish something together while respecting their singularities. Further, free action is not enacted with the hope of obtaining an external result but rather of forming a political space that “lives” and breathes thanks to shared solidarity and vital, dynamic spontaneity.

Our analysis of a libertarian fantasy—based on the work of Hannah Arendt—shows that by working with a sole objective of producing more, individuals fall into the modern incarnation of acting in bad faith. This submission is driven by a deceptive—and ultimately self-defeating—belief that individuals will feel freer by performing better. At a time, when an ecological and a social urgency is becoming even more acute, an Arendtian perspective detects drifts in hypernorms of neoliberalism and triumphant heroization of individual career success. Our study sets a path for further inquiries that could focus on ideologically transgressive organizations that adopt a broader definition of success (or forsake it altogether) and respect the singularity of individuals by actively enabling the formation of working communities, welcoming the fruits of collective labor, and offering non-prescriptive forms of professional self-actualization. Several studies have already examined organizations that are concerned with the common good and resistant to totalitarian practices, as they strive to pursue the dual ideal of a community good and the personal good of all community members (Frémeaux and Michelson 2017; Sison and Fontrodona 2012). Future research can use the reflections presented in this article to add to the principles of the common good most commonly emphasized in the current literature—subsidiarity, totality, teleological hierarchy, long-term commitment, reality, or unity (Frémeaux et al. 2020a, b). Furthermore, we animate scholars interested in career studies to contribute to a critical examination of the different ways of experiencing professional success, dynamics of cooperation, and spontaneous activities. This attention to other aspects of the common good can provide a better understanding of how organizations can abandon or loosen the ideology of performance centered on objective, instantaneously visible and quantifiable results.

Organization scholars who study the challenges of empowerment and emancipation at workplace can further advance their understanding of these issues by looking at how individuals and collectives free themselves from a libertarian fantasy by opting for true human freedoms. For example, Agamben (2007) refers to acts of “profanations” that—as observed in children’s playing of games—create space for ideological suspension and remain immune to ideological codification of reactions and behaviors. The multiple movements of liberation management (Laloux 2014) and liberated companies (Getz 2009; Sferrazzo and Ruffini 2019) can be relevant observation spaces as they elevate freedoms to the level of supreme values and raise the question of whether these freedoms are the signs of the libertarian fantasy or constitute profoundly human freedoms. We encourage researchers to address this question, and that of the hierarchy of freedoms, in organizations or communities that promote autonomy, individual responsibility, and self-management.

A rehabilitated form of political action in a new corporate governance perspective—that respects human singularity, solidarity, and spontaneity—preserves true freedoms and eliminates emerging forms of totalitarianism. In this respect, it provides a much-needed safeguard to counter the actions of bad faith that afflict corporate and public life and helps shift these collectives away from the torments of the weakening of politics and the dictates of what Pierre Musso (2019) called Le temps de l’Etat-entreprise.

References

Agamben, G. (2007). Profanations. Cambridge, MA: Zone Books.

Ahsan, M. (2018). Entrepreneurship and ethics in the sharing economy: A critical perspective. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3975-2.

Alvesson, M., & Robertson, M. (2006). The best and the brightest: The construction, significance and effects of elite identities in consulting firms. Organization, 13(2), 195–224.

Alvesson, M., & Spicer, A. (2016). (Un)conditional surrender? Why do professionals willingly comply with managerialism. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 29(1), 29–45.

Anderson, E. (2017). Private government: How employers rule our lives (and why we don’t talk about it). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Arendt, H. (1951). The origins of totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt Brace & Co.

Arendt, H. (1958). The human condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Arendt, H. (1960). Freedom and politics: A lecture. Chicago Review, 14(1), 28–46.

Arendt, H. (1961). What Is Freedom? Between past and future (pp. 143–171). New York: Viking Press.

Arendt, H. (1972). Crises of the republic. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Arnold, D. (2003). Exploitation and the sweatshop quandary. Business Ethics Quarterly, 13(2), 243–256.

Bailey, C., Madden, A., Alfes, K., Shantz, A., & Soane, E. (2016). The mis-managed soul: Existential labor and the erosion of meaningful work. Human Resource Management Review, 27(3), 416–430.

Bal, P. M., & Dóci, E. (2018). Neoliberal ideology in work and organizational psychology. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 27(5), 536–548.

Bauman, Z., Bauman, I., Kociatkiewicz, J., & Kostera, M. (2015). Management in a liquid modern world. New York: Wiley.

Berardi, F. (2012). The uprising: On poetry and finance. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

Berardi, F. (2015). Heroes: Mass murder and suicide. London: Verso Books.

Blanc, S. (2016). Are Rawlsian considerations of corporate governance illiberal? A reply to Singer. Business Ethics Quarterly, 26(3), 407–421.

Block, F., & Somers, M. R. (2014). The power of market fundamentalism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1996) [1989]. The state nobility. Elite schools in the field of power. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Clegg, S. (2014). Managerialism: Born in the USA. Academy of Management Review, 39, 566–585.

Cohen, J., & Rogers, J. (1995). Associations and democracy. London: Verso.

Crary, J. (2014). 24/7: Late capitalism and the ends of sleep. London: Verso Books.

Edward, P., & Willmott, H. (2008). Corporate citizenship. Rise or demise of a myth. Academy of Management Review, 33(3), 771–773.

Edward, P., & Willmott, H. (2008). Structures, identities and politics: Bringing corporate citizenship into the corporation. In A. Scherer & G. Palazzo (Eds.), Handbook of research on global corporate citizenship (pp. 405–429). Cheltenham: Edward Edgar Publishing.

Edwards, M. A., & Roy, S. (2017). Academic research in the 21st century: Maintaining scientific integrity in a climate of perverse incentives and hypercompetition. Environmental Engineering Science, 34(1), 51–58.

Ehrenberg, A. (1991). Le culte de performance. Paris: Callman-Levy.

Fine, B., & Saad-Filho, A. (2017). Thirteen things you need to know about neoliberalism. Critical Sociology, 43, 685–706.

Fleming, P. (2014). Review article: When « life itself » goes to work. Reviewing shifts in organizational life through the lens of biopower. Human Relations, 67(7), 875–901.

Fleming, P. (2017). The human capital hoax: Work, debt and insecurity in the era of uberization. Organization Studies, 38(5), 601–709.

Frémeaux, S., & Michelson, G. (2017). The common good of the firm and humanistic management: Conscious capitalism and economy of communion. Journal of Business Ethics, 145(4), 701–709.

Frémeaux, S., Puyou, F., & Michelson, G. (2020). Beyond accountants as technocrats: A common good perspective. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 67–68, 1–14.

Frémeaux, S., Bardon, T., & Letierce, C. (2020). How to be a “wise” researcher: Learning from the Aristotelian approach to practical wisdom. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04434-3.

Friedman, M. (1992). Capitalism and freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Foucault, M. (2008). The birth of biopolitics. London: MacMillan Publishers.

Gabriel, Y. (2005). Class cages and glass palaces: Images of organizations in image-conscious times. Organization, 12(1), 9–27.

Gandini, A. (2019). Labour process theory and the gig economy. Human Relations, 72(6), 1039–1056.

Gardiner, R. A. (2017). Ethical responsibility—An Arendtian turn. Business Ethics Quarterly, 28(1), 31–50.

Gardiner, R. A., & Fulfer, K. (2017). Family matters: An Arendtian critique of organizational structures. Gender, Work & Organization, 24(5), 506–518.

George, J. M. (2014). Compassion and capitalism: Implications for organization studies. Journal of Management, 40, 5–15.

Getz, I. (2009). Liberating leadership: How the initiative freeing radical organizational form has been successfully adopted. California Management Review, 51(4), 32–58.

Gleadle, P., Cornelius, N., & Pezet, E. (2008). Enterprising selves: How governmentality meets agency. Organization, 15(3), 307–313.

Glynos, J. (2008). Ideological fantasy at work. Journal of Political Ideologies, 13, 275–296.

Glynos, J., & Howarth, D. (2007). Logics of critical explanation in social and political theory. London, New York: Routledge.

Gomez, P.-Y. (2013). Le Travail invisible. Enquête sur une disparition. Paris: François Bourin éditeur.

Grey, C. (1996). Towards a critique of managerialism: The contribution of Simone Weil. Journal of Management Studies, 33(5), 591–611.

Harvey, D. (2005). Neoliberalism: A brief history. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hayek, F. A. (1994). The road to serfdom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Heath, J., Moriarty, J., & Norman, W. (2010). Business ethics and (or as) political philosophy. Business Ethics Quarterly, 20(3), 427–452.

Hennekam, S., & Shymko, Y. (2020). Coping with the COVID-19 crisis: Force majeure and gender performativity. Gender, Work, and Organization,. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12479.

Henning, G. (2011). Corporation and Polis. Journal of Business Ethics, 103(2), 289–303.

Herman, E. S., & Chomsky, N. (1988). Manufacturing consent: The political economy of the mass media. New York: Pantheon Books.

Honig, B. (2001). Dead rights, live futures: A reply to Habermas’s ‘Constitutional Democracy.’ Political Theory, 29(6), 792–805.

Jones, S. (2012). Masters of the universe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Knight, J., & Johnson, J. (2011). The priority of democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kohn, J. (2002). Arendt’s concept and description of totalitarianism. Social research, 69(2), 621–635.

Laloux, F. (2014). Reinventing organizations. Belgium: Nelson Parker.

Larson, R. (2018). Capitalism vs. freedom: The toll road to serfdom. Winchester, UK: Zero Books.

Lazzarato, M. (2004). Les révolutions du capitalisme. Paris: Les Prairies Ordinaires.

Lazzarato, M. (2009). Neoliberalism in action: Inequality, insecurity and the reconstitution of the social. Theory, Culture & Society, 26, 109–133.

Lazzarato, M. (2014). Signs & machines. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

Lazzarato, M. (2015). Governing by debt. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

Lievens, M., & Kenis, A. (2015). The limits of the green economy. London: Routlege.

Lips-Wiersma, M., & Morris, L. (2009). Discriminating between ‘meaningful work’ and the ‘management of meaning.’ Journal of Business Ethics, 88(3), 491–511.

Logsdon, J. M., & Wood, D. J. (2002). Business citizenship: From domestic to global level of analysis. Business Ethics Quarterly, 12, 155–188.

Malsch, B., & Guénin-Paracini, H. (2013). The moral potential of individualism and instrumental reason in accounting research. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 24(1), 74–82.

Marcuse, H. (1968). Negations: Essays in critical theory. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Micali, S. (2010). The capitalistic cult of performance. Philosophy Today, 54(4), 379–391.

Musso, P. (2019). Le temps de l’État-entreprise. Berlusconi, Trump, Macron. Paris: Fayard.

Niebuhr, R. (1932) [2002]. Moral man and immoral society: A study of ethics and politics. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press.

Nielsen, R. P. (1984). Toward an action philosophy for managers based on Arendt and Tillich. Journal of Business Ethics., 3(2), 153–161.

Norman, W. (2015). Rawls on markets and corporate governance. Business Ethics Quarterly, 25(1), 29–64.

Néron, P.-Y., & Norman, W. (2008). Citizenship, Inc. Business Ethics Quarterly, 18(1), 1–26.

Pettit, P. (2001). A theory of freedom: From the psychology to politics of agency. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Petriglieri, G., Ashford, S. J., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2019). Agony and ecstasy in the gig economy: Cultivating holding environments for precarious and personalized work identities. Administrative Science Quarterly, 64, 124–170.

Polanyi, K. (2001) [1944]. The great transformation. Boston: Beacon Press.

Renou, G. (2010). Les laboratoires de l’antipathie: À propos des suicides à France Télécom. La Revue du MAUSS, 35(1), 151–162.

Rodriguez, M. (2008). The challenge of keeping a world: Hannah Arendt on administration. Polity, 40(4), 488–508.

Sferrazzo, R., & Ruffini, R. (2019). Are liberated companies a concrete application of sen’s capability approach? Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04324-3.

Sennett, R. (2003). The fall of public man. London: Penguin.

Sennett, R. (2003). Respect in a world of inequality. London: WW Norton & Company.

Singer, A. (2015). There is no Rawlsian theory of corporate governance. Business Ethics Quarterly, 25(1), 65–92.

Sison, A. J., & Fontrodona, J. (2012). The common good of the firm in the Aristotelian-Thomistic tradition. Business Ethics Quarterly, 22(2), 211–246.

Slee, T. (2017). What's yours is mine: Against the sharing economy. Or Books.

Snyder, J. (2010). Exploitation and sweatshop labor: Perspectives and issues. Business Ethics Quarterly, 20(2), 187–213.

Stiegler, B. (2008). Acting out. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Suarez-Villa, L. (2012). Technocapitalism: A critical perspective on technological innovation and corporatism. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Thompson, G. F. (2005). Global corporate citizenship: What does it mean? Competition & Change, 9(2), 131–152.

Tillich, P. (1934). The totalitarian state and the claim of the Church. Social Research, 1(4), 405–433.

Velasquez, M. (2003). Debunking corporate moral responsibility. Business Ethics Quarterly, 13(4), 531–562.

Weil, S. (1933) [1988]. Oppression and liberty. London: Routledge.

Wood, D. J., & Logsdon, J. M. (2008). Business citizenship as metaphor and reality. Business Ethics Quarterly, 18(1), 51–59.

Vassort, P. (2012). L’homme superflu. Théorie politique de la crise en cours. Congé-sur-Orne: Le Passager Clandestin.

Verhaeghe, P. (2012). What about me?: the struggle for identity in a market. London: Scribe Publications.

Visser, M. (2019). Freedom, recognition and precarity in organizations: Master & slave in the 21st century. Working Paper presented at 35th EGOS Colloquium.

Žižek, S. (1989). The sublime object of ideology. London: Verso Books.

Acknowledgements

We wish to convey our thanks and appreciation to Dr Alejo Jose G. Sison,—Editor of the section ‘Philosophy and Business Ethics’—for his editorial direction, and to the anonymous reviewers for their generous and thoughtful comments. We would like to thank Alison Minkus and Ariane Berthoin Antal for their help and valuable feedback on the earlier version of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest and no financial support for the authorship of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shymko, Y., Frémeaux, S. Escaping the Fantasy Land of Freedom in Organizations: The Contribution of Hannah Arendt. J Bus Ethics 176, 213–226 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04707-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04707-x