Abstract

The importance of relationality in ethical leadership has been the focus of recent attention in business ethics scholarship. However, this relational component has not been sufficiently theorized from different philosophical perspectives, allowing specific Western philosophical conceptions to dominate the leadership development literature. This paper offers a theoretical analysis of the relational ontology that informs various conceptualizations of selfhood from both African and Western philosophical traditions and unpacks its implications for values-driven leadership. We aim to broaden Western conceptions of leadership development by drawing on twentieth century European philosophy’s insights on relationality, but more importantly, to show how African philosophical traditions precede this literature in its insistence on a relational ontology of the self. To illustrate our theoretical argument, we reflect on an executive education course called values-driven leadership into action, which ran in South Africa, Kenya, and Egypt in 2016, 2017, and 2018. We highlight an African-inspired employment of relationality through its use of the ME-WE-WORLD framework, articulating its theoretical assumptions with embodied experiential learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Research on ethical leadership development in Africa remains underdeveloped (Smit 2013). As such, a tacit assumption that Western approaches to leadership development suffice in supporting African leaders in their role as champions of values-driven business, may underpin both theory and practice within African and other non-Western contexts. Even more disturbingly, this absence may also reflect persistent colonial and neo-colonial biases in favour of Western philosophical tradition in ethics education on the African continent (see Nkomo 2011; Murphy and Zhu 2012; Alcadipani et al. 2012; Smith 2013, for general discussions of these issues in management and research). In response to these risks, we will illustrate that there is much to be learned from the African context’s diversity and richness in terms of underlying philosophical basis and empirical developments that could inform and enhance business ethics theory, practice and education more broadly. The creation of the African Journal of Business Ethics in 2005, and compilations of works like the virtual special issue on advancing business ethics research on Africa in the Journal of Business Ethics (Muthuri et al. 2017), and this volume are all important steps in this direction. They reflect a growing interest in the contributions that can originate in this part of the world (George et al. 2016; Kolk and Rivera-Santos 2016) which remain understudied; an interest also empirically visible through the burgeoning initiatives that have sprung worldwide from a variety of perspectives.

In this paper, we wish to further contribute to this growing body of work by focusing on African-inspired theoretical and pedagogical contributions to the area of ethical leadership development (Khoza 2006; Smit 2013), and more specifically to the importance of relationality in ethical leadership. Indeed, relational leadership is a rather recent issue both in general leadership studies (Cunliffe and Eriksen 2011), and in ethical and critical leadership studies (Maak and Pless 2006; Liu 2017; Rhodes and Badham 2018). However, relationality is a core feature and longer-standing concern of the African tradition of Ubuntu. Originating in southern Africa, this idea can be translated as “I am we; I am because we are, we are because I am” (Goduka 2000; Sulamoyo 2010). Under this principle, reality itself is understood relationally, in and by relationships. In the words of Nobel Peace laureate Desmond Tutu: others and community constitute “the very essence of being human. (…) It is not ‘I think therefore I am’. It says rather ‘I am human, therefore I belong, I participate, I share’” (Tutu 1999, p. 31). Within this conception, “The ‘we’ is an overarching notion that both supersedes and honours the individual identities within it” (Louw 2010, cited in Tavernaro-Haidarian 2018, p. 18).

Following recent works demonstrating the value of bringing together African and Anglo-American or other Western intellectual traditions, we believe there is an interesting opportunity to expand present theorizing on relational ethical leadership, this time from an African perspective. Several recent works have laid important foundations in this direction. For instance, Lutz (2009) suggested that the way Ubuntu philosophy places the community at the centre could help global management more adequately address issues pertaining to the common good. Woermann and Engelbrecht (2017) build on Ubuntu to conceptualize stakeholders as relation holders, once again insisting on the interconnections that knot human beings and communities together. Hoffmann and Metz (2017) demonstrate the value of bringing together African and Anglo-American intellectual traditions in their study of what the capabilities approach can learn from an Ubuntu ethic in the context of development theory. The capabilities approach emerged in the 1980s as an alternative approach to development and welfare economics, largely founded by Amartya Sen (1999) and Martha Nussbaum (2000). Hoffmann and Metz (2017) suggest that the more individualistic notions of freedom to realize one’s valued human ‘capabilities’ are not in direct contrast to the communality of an Ubuntu ethic. Rather, they argue that an Ubuntu reading draws attention to the centrality of a relational ethic within the concept of capability and the relational properties of capabilities, and as such should inform new normative perspectives on capabilities. This application of Ubuntu to established conceptual approaches was also adopted by Tavernaro-Haidarian (2018) who draws on Ubuntu to frame a relational model of communication based on the premise that the interests of individuals and groups are ‘profoundly bound-up’, rather than incompatible. In Ubuntu, leadership is about mutuality and communal relationships based on harmony and fellowship. The centrality of consensus and communal relationships has implications for leadership, because from an Ubuntu perspective the leadership function becomes a process of learning for both ‘facilitator’ and ‘participant’” (Blankenberg 1999, p. 46, in Tavernaro-Haidarian 2018). Drawing on the central Ubuntu idea that human interests are inherently bound-up and interrelated, we suggest that a core goal of ethical leadership is to work toward the greater good of others (Tavernaro-Haidarian 2018).

However, this burgeoning literature has had little cross-fertilization with most of the ethical leadership and relational leadership literatures. Two explanations can be advanced for this. First, Western scholars can easily tend to see them as ‘exotic’ contributions whose theoretical relevance remains marginal in other contexts, as post-colonial theorists have argued (Ibarra-Colado 2006; Nkomo 2011; Alcadipani et al. 2012 among others). Second, most of these works offer theoretical or philosophical discussions of Ubuntu, but few explain how to translate the principles behind it into practice, thus undermining its empirical relevance in the eyes of many scholars who therefore remain largely unfamiliar with it.

Our paper seeks to address these two issues, firstly by establishing a theoretical dialogue among both traditions and proposing an African-rooted contribution to relational ethical leadership theory, and secondly by showing how this can effectively be put into practice through a pedagogical design. To do so, we draw on an executive education course called values-driven leadership into action (VDLA), which has run several times in South Africa, Kenya, and Egypt in 2016, 2017, and 2018. Taking its inspiration from the African context within which it was initiated, the course design presents several characteristics of interest for global business ethics scholars.

First, contrary to most research on business ethics in Africa which tends to focus on country or region-specific cases and surveys which indeed carry significant local insights (e.g. see the collection of Ike 2011; Kagabo 2011; Mawa and Adams 2011; Smurthwaite 2011; and the summary made by Rossouw 2011), VDLA purposefully takes a pan-African approach, where theoretical bases and participants come from a variety of countries, professions, sectors and backgrounds. From its inception, it has incorporated this multi-country, multi-stakeholder perspective, thus fostering rich conversations and contributing to its broader relevance. Second, the course takes an experiential learning approach, which displays the evocative power of a relational ontology rooted in Ubuntu. Third, the exercises developed in the course incorporate both African philosophical traditions such as Ubuntu and the continent’s strength in story-telling, combining these with Western contributions, namely Mary Gentile’s (2010, 2011, 2012, 2013) ‘Giving Voice to Values’ (GVV) approach to pedagogy, which has been implemented across the globe in various cultural and emerging contexts such as India. The VDLA goes beyond GVV in its unique approach to developing relationality through its African experiential pedagogy and exercises tailored to exert this in the context of ethical leadership education.

The VDLA content evolved through the pilot phases into a unique three-day course that engages leaders across various sectors in a course that we believe illustrates a relational approach to values-driven leadership in a way which connects Western and African ontologies. It does so in two distinct ways: Firstly, theoretically, the course takes a relational accountability approach to actions on individual, group and societal levels through what it calls the ME-WE-WORLD framework. The VDLA starts with identifying the affective and relational roots of participants’ personal normative beliefs, and proceeds to relate these beliefs to the role they and their organizations can play in addressing systemic societal issues. Secondly, methodologically, the course employs experiential techniques that connect participants, thereby putting Ubuntu philosophy into practice in ethical leadership education.

This paper is structured as follows. We begin by reviewing the literature on ethical leadership, and how recent contributions that include a relational perspective are both at a nascent stage and mostly inspired by Western ontologies and philosophies. Second, we outline a theoretical framework where the longer-standing tradition of Ubuntu can directly speak to the challenges of fostering a relational ethical leadership. To our knowledge, Ubuntu has not been employed in a practical setting on ethical leadership education. We illustrate our argument with the theoretical and experiential aspects of the VDLA course, particularly focusing on one of its key exercises: the ‘dream-board exercise’. Thirdly, our discussion section will unpack the theoretical and methodological contributions of this African initiative to ethical leadership education and theory more broadly, and will end by discussing potential avenues for pursuing these implications in the course’s future occurrences both in African and Western settings.

Ethical Leadership and Relationality: A Review of the Literature

Relational Selves from the Perspective of Western Philosophy

In response to the various disillusionments with the disembodied, ‘rational’ calculating subject that Western thought inherited from the Enlightenment, poststructuralist philosophers in Europe offer us a more nuanced conception of our own subjectivity. They have contributed significantly to dismantling the subject-object distinction that lies at the heart of our ontologies and epistemologies. It took a while for scholars in organizational theory to start paying attention to the implications of these philosophers for business ethics (Ibarra-Colado et al. 2006; Ladkin 2006; Byers and Rhodes 2007; Jones 2007; Deslandes 2012; Painter-Morland 2012, 2013; Pérezts et al. 2015). In the past 10 years, several books have also appeared claiming to take this approach to the field of business ethics (Jones et al. 2006; Painter-Morland and Ten Bos 2011).

In the European tradition, multiple philosophers offer us rich insights with regards to the relational dynamics that underpin our sense of selfhood. Scholars have drawn on multiple European philosophers, such as Deleuze (Painter-Morland 2012, 2013) Heidegger (Bakken et al. 2013; Blok 2014), Kierkegaard (Deslandes 2011a), Levinas (Bevan and Corvellec 2007), Pascal (Deslandes 2011b), Merleau-Ponty (Kupers 2013; Ladkin 2012), Henry (Faÿ and Riot 2007; Faÿ et al. 2010; Pérezts et al. 2015) and Ricoeur (Deslandes 2012) to help us understand what this relationality entails in the context of organizational life (Painter-Morland 2018).

To mention just one example, Merleau-Ponty’s notion of the ‘flesh’ articulates the way in which our sensate, perceptive bodies are intertwined with the sensible world. This goes some way towards helping us understand what Cooper (2005, p. 1690) calls the ‘interspace’ between humans and their environment which emerges as the prime mover of human agency. Merleau-Ponty explains that perception is a two-way, dynamic and interactive process (Ladkin 2012). Thus, when I perceive another person, I am also aware that s/he can perceive me, and my perception is always already altered by this awareness. To articulate the qualitative experience that this constant interplay creates, Merleau-Ponty coined the term “percipient perceptibles”. It allows us to understand the way in which others’ perceptions of us are integrated within our self-concept and how it informs our own perceptive embodiment. This has inspired organizational theorists such as Ladkin (2012) to argue that we should not overlook the fact that without bodies, the perceptions that create the relational space for ethics would not be possible. This reconceptualization of agency from an embodied point of view has also allowed a reconsideration of the validity of assuming the existence of homo economicus, the calculating agent maximizing his or her self-interest, as the centre of organizational life. This critique has allowed a number of other alternative proposals to emerge: homo reciprocans, homo ludens, homo ecologicus, etc. (Painter-Morland 2018).

Critical reflections on ethical approaches that make the transcendental subject the locus of action, also extends to justice-theories. In his analysis of the conceptions of justice that inform organizational ethics, Rhodes (2011) highlights that the most prominent contemporary theory that informs our thinking is that of John Rawls, also described as the ‘justice as fairness’ approach. This approach to justice argues that the relations between people and organizations should be arranged to ensure the fair distribution of rights, duties and benefits among all involved. The principle of justice as fairness lies at the heart of social contracts, and as such, it assumes the existence of calculating individual subjects negotiating for their own benefit. In articulating a poststructuralist response to prominent justice-theories that are designed to avoid some getting more than others (pleonexia), Rhodes (2011) draws on Levinas to reframe the locus of agency from the individual self who is trying to negotiate his/her fair share, towards the ‘Other’, whose existence demands an ethical response, even when self-interest or legal obligation may not dictate it (Rhodes 2012). In this way, a Levinasian approach to ethics is decidedly relational in a way that Rawlsian principles are not.

Overall, the European poststructuralist tradition has not had a very strong influence on American approaches to business ethics thus far, with most textbooks exclusively drawing on Anglo-American analytic philosophy. There has however been a growing awareness that though European philosophy is helpful in informing decision-making models such as utilitarianism and deontology, it often falls short in terms of inspiring values-driven action and leadership, as we will discuss hereafter.

Ethical Leadership and Relationality

The connection between ethics and leadership is longstanding and the role that individual leaders can play in facilitating ethical action is well documented. When ancient political philosophers, from both East and West advised and reflected on the power figures of their time, they were already theorizing on the leader and leadership with a deep sense of the responsibility and ethics behind it (Prastacos et al. 2012). More recently, the ethical aspects of leadership have been defined in terms of strong or exemplary personality traits, making them worthy of their followers, sometimes almost in a religious sense (Grint 2010). The notion of servant leadership for instance also shares this quasi-religious terminology of serving; the leader being in the service of followers in order to humbly develop them and provide them with guidance (van Dierendonck 2011). In a recent paper, Walton (2018, p. 109) shows leaders’ ‘positive deviance’ in insisting on their organizations’ divestment in fossil fuel investments can be extremely influential in terms of energizing a broader group of individuals and institutions towards supporting sustainability agendas. The mission-alignment between individual leaders and the decisions and actions taken by their organizations is central to them acting as catalysts for change. Others have noted how our reflected and portrayed ‘best self’ (Roberts et al. 2005) is both “an anchor and a beacon, a personal touchstone of who we are and a guide for who we can become” (2005, p. 712), thereby implying that the organization can propel or hinder each person’s ‘best’, i.e. their strengths and contributions. However, such conceptions focus on the individual figure of the leader, somewhat neglecting that leaders are only leaders in and through the relationships that bind them with followers.

Towards a more Relational Conception of Leadership

More process-oriented approaches stress the fact that individual leaders do not lead in isolation, shifting the attention from the individual leader as the unit of analysis to the web of leadership connections, and the processes and practices by which these are constructed, maintained or challenged (Crevani et al. 2010). Some have advanced the importance of conceiving these processes as processes of relationality (Fairhurst and Uhl-Bien 2012) and coined the notion relational leadership (Uhl-Bien 2006; Cunliffe 2009). The importance of relationality and its dialectics, paradoxes, and dilemmas are well established in organization studies and critical leadership studies (Cooper 2005; Collinson 2005; 2014; Cunliffe and Eriksen 2011). Yet its reception in the field of ‘relational leadership’ still reveals certain distinct impasses.

Most importantly, the literature continues to grapple with seemingly incommensurable paradigms, which Uhl-Bien and Ospina (2012) describe as the tension between ‘entity’ perspectives and ‘constructionist’ perspectives. The former is positioned as closer to the ‘objectivist’ epistemological position, whereas the latter is portrayed as ‘subjectivist’. The underlying distinction between ‘objective’ and ‘subjective’ echoes other problematic binaries such as ‘facts’ versus ‘values’, ‘reason’ versus ‘emotion’, ‘mind’ versus ‘body’, ‘hard’ systems versus ‘soft’ systems etc. Such distinctions have been challenged from the perspective of contemporary continental philosophy and sociology (Painter-Morland 2013), resulting in a relational ontology that describes ‘identity’ as an emergent product of the interrelation of individuals with others, i.e. other persons, but also animate and inanimate entities (Painter-Morland and Deslandes 2017). From this perspective, leaders’ sense of ‘direction’ goes beyond the relationship between leaders and followers, and much further than their mutual constructions of each other. Here we follow Painter-Morland and Deslandes (2017) in arguing that embodied processes of habituation, physical and virtual organization, discursive practices all conspire to create certain relational constraints, which are not mere ‘subjective’ constructions.

Furthermore, recently Rhodes and Badham (2018) for instance have argued that failing to acknowledge the power embedded in the relations between leaders and followers is a major shortcoming of relational ethical leadership, since it can result in the seeming incommensurability of the ethical demands that a relational ethic in leadership implies. The contribution of Levinasian ethics (e.g. Bevan and Corvellec 2007), places this embodied tension of incommensurability in the foreground, thereby speaking directly to the lived experience of participants who might face difficult leadership situations where ethics—and their ability to lead and act ethically—are compromised. Drawing on the relational phenomenology of Michel Henry, Pérezts et al. (2015) have argued that it is in the inter-corporeal and embodied connections that a team and its ethical leader can build an esprit de corps and find the strength to collectively fight the pressure to behave unethically in complex business situations.

Such relations imply dependability and accountability between individuals, thereby infusing relational leadership with a particular attention to ethics in this on-going process (Maak and Pless 2006; Painter-Morland 2008a; Cunliffe and Eriksen 2011). Values-driven leadership emerges from the relational orientation that emerges as sensing, perceptive bodies enter into complex sets of inter-relations. Out of these inter-relations, feelings, cognitions, meanings, as well as communities, artefacts, structures and functions are constantly being created, questioned, recreated and renegotiated (Kupers 2013). New values, behaviours and social dynamics emerge and are continually renegotiated. In transitional periods, one can witness ‘inter-leadership’ within which the transitional dimensions of selves, agents, cultures and systems are complexly interconnected (Kupers 2013).

Leadership Development and Education

One specific contribution to values-driven leadership is Mary Gentile’s (2010, 2011, 2012, 2013) Giving Voice to Values (GVV), which was influential in the design of the VDLA course, as described later in the paper. GVV has become a well-established approach to values-driven leadership development (Gentile 2013), with multiple applications worldwide. It starts from the premise that whilst many individuals in organizations may know what the right thing to do is, they often simply think it is impossible to take this action. Instead of focusing on ethical decision-making and the dilemma discussions that traditional business ethics curricula usually focus on, it is a ‘post-decision making’ tool aimed at action: “once you know what you believe is right, how can you get it done, effectively?” (Arce and Gentile 2015, p. 537). Additionally, it is profoundly relational in its methodology in that it focuses on mapping all the parties involved and identifying their stakes in the problem, as well as arguments to work with some or against others in getting the right thing done. Finally, it aims at empowering individuals and equipping them with a set of tools to work their way through the conflicting situations they are bound to encounter.

Following what we saw in the previous section, these insights on the self as a relational being have been slow to filter through to the leadership literature, with the first major text exploring the construct of relational leadership published in 2012 (Uhl-Bien and Ospina 2012). Articles drawing on European philosophy to rethink leadership have also been limited in number (Ladkin 2012; Rhodes 2012; Painter-Morland and Deslandes 2014; Blom and Alvesson 2015; Bouilloud and Deslandes 2015). We believe that African traditions have a much longer tradition of acknowledging relationality and embodied subjectivity that shirks subject-object dualisms, and that much can be learnt from its implications for leadership development. We also suggest that the VDLA course draws on this kind of relational ontology, and that it is important to articulate the contribution that African philosophy makes to understanding such an ontology, and to highlighting its practical implications.

An African-Inspired Theoretical Framework for Relational Ethical Leadership

"A concept like Ubuntu cannot be understood in a monolithic way. It can be compared to a river that breaks into tributaries and forms many islands around which its water flows and later converges and forms one big river" (Kgatla 2016, p. 2).

Ubuntu, Relationality and Ethics

While pertaining to the southern part of the African continent originally, numerous works have stressed that the essence of relationality behind Ubuntu is both historical and diffused, and cannot be said to be country or region specific. For instance, McDonald (2010) considers it an ‘African worldview’ and Nussbaum characterizes Ubuntu as “an underlying social philosophy of African culture” and one of “the inspiring dimensions of life in Africa” (2003, p. 1). This is why in the introduction we mentioned that relationality is a core feature and longer-standing concern of such African philosophical traditions preceding some of the Western preoccupations with ethical relational leadership, by grounding interconnectedness in a relational ontology of the self. While Western Cartesianism has favoured placing the individual in the foreground, almost independently of everyone and everything else, Ubuntu stresses “an I/we relationship as opposed to the Western I/you relationship with its emphasis on the individual” (Chilisa 2012, p. 21; cf. Tutu 1999). The individual does not exist independently from the collective whose interests lie above those of the individual, who is in turn bound by the community in its human essence (McDonald 2010). Fundamentally, Ubuntu “…addresses our interconnectedness, our common humanity and the responsibility to each other that flows from our deeply felt connection” (Nussbaum 2003, p. 1). As such, it offers a relational approach to morality and ethics grounded in harmony, and brings a different ethos to Western approaches, which prioritise utility, autonomy and capability (Metz 2014).

As suggested by the opening quote of this section, although the general spirit behind Ubuntu is relatively simple to understand, it is far from being simplistic. Four elements need to be noted here. To begin with, as McDonald reminds us:

“there is no easy or direct translation to English, and there are unresolved debates about its ontological status. Morphologically, Ubuntu is an Nguni term, with phonological variants in many African languages, including umundu in Kikuyu, imuntu in Kimeru, bumuntu in kiSukuma, vumuntu in shiTsonga, bomoto in Bobangi, and gimuntu in kiKongo (Kagame 1976, as cited in Kamwangamalu 1999, p. 25). For Ramose (2002a, p. 230), it is critical to see the word as ‘two words in one’, consisting of the prefix ubu- and the stem ntu-, evoking a dialectical relationship of being and becoming. In this sense, ubu- and ntu- are ‘two aspects of being as a one-ness and whole-ness’, with ubuntu best seen as a dynamic interplay between the verb and the noun rather than a static or dogmatic state of thinking” (2010, p. 14).

The key words here are ‘one-ness’ and ‘whole-ness’ and the conception that being is both relational and dialectical, i.e. it cannot be understood solely by one of these aspects, but as intricately linked, as two sides of the same coin.

If we go into a more detailed conception, Praeg (2017) points to two different ways of framing Ubuntu. First, as African Humanism (see for example Metz 2014), which speaks of the core values of friendliness, love and harmony, and the moral quest to ‘do the right thing’ towards unity (Praeg 2017). Second, Ubuntu can be described as African Communitarianism, which contains a ‘dark’ side that is political, and can also include violence, discipline, coercion and persuasion in the pursuit of unity and the common good, with significant implications for post-colonial moral theorizing (Praeg 2017, p. 295). Tavernaro-Haidarian (2018) deals with the challenge of the ‘communitarian’ aspect by viewing Ubuntu as an ideal theory rather than its historic or anthropological iterations, concluding that the significant value of Ubuntu can be its role in evolving society in a forward looking manner. We draw on this approach, whilst recognizing that the communitarian aspect also has important implications for values-driven leadership in practice, and thus cannot be ignored.

Third, besides theoretical complexity, one must be careful not to oversimplify the historical construction and current reach of Ubuntu thought. For instance, Stacy (2015) and Praeg (2017) provide useful insights on the divergent framings of Ubuntu. Firstly, as a pre-colonial, historical and cultural African logic of interdependence among a visible (perhaps tribal) community; disrupted by colonialism and the hegemony of individual liberalism. Secondly, Ubuntu, as an abstract post-colonial philosophical construct, that is both influenced by, and influences major discourses (e.g. on human rights) and everyday politics, particularly in South Africa. The potential of Ubuntu as an emancipatory concept, particularly in South Africa has been discussed by various African academics (see for example McDonald 2010; Praeg 2014; Stacy 2015). For instance, McDonald (2010) discusses how the philosophy and language of Ubuntu have been appropriated by market ideologies in post-apartheid South Africa, but suggests that the transformative nature of Ubuntu beliefs and practice can reinvigorate the discourse of socialist/anti-capitalist movements. Furthermore, Praeg (2017) argues that it is a common mistake in many Western approaches to Ubuntu to neglect its political dimensions and assumptions rooted in its complex historical construction:

“…thinking Ubuntu is a political act before it becomes an epistemological, ontological or ethical answer to anything; that by thinking Ubuntu we are implicitly doing politics long before we get to do what we explicitly aim to do, namely to explore epistemology, ontology or ethics” (Praeg 2017, p. 294).

Finally, and linked to what has just been said, Ubuntu thinking is far from being an idealistic conception devoid of considerations of power. It is infused with the desire to reconcile ambiguous and conflicting situations. Here again, it offers a relational perspective on these issues. Rather than a conflictual approach of right or wrong, or ‘power to’ or ‘power over’, Ubuntu offers relational notions of power that can counteract the I/you dichotomy, providing a space for collaboration and deliberation where power is inclusive, and grows between people (Tavernaro-Haidarian 2018, p. 27, 35). It is in this regard, that an Ubuntu ethic also moves beyond the kind of Rawlsian ‘justice-as-fairness’ principles that we discussed earlier. Where Rawlsian justice requires of us to negotiate fair distribution of benefits and duties between distinct parties, an Ubuntu orientation disrupts a view of the self which allows us to pit one person or party’s interests against another.

Furthermore, Western ways of thinking and constituting knowledge have largely been characterized by a binary either/or logic (for a recent exception see the paradox theory literature, and its application for resolving business ethics dilemmas and contradictions, e.g. Pérezts et al. 2011). In contrast, an Ubuntu orientation refuses to submit to binary alternatives and mutually exclusive solutions, “Our affairs and realities can be thought of as bound-up, complementary and open-ended, encouraging a vast diversity of views and voices. Commonalities and overlaps can be found and emphasized and related social action enabled” (2018, p. 37).

Ethical Relational Leadership from an African Perspective

As mentioned earlier, the area of ethical leadership development has been identified by African scholars as a key priority in business education and development in the region (Khoza 2006; Smit 2013; Hoffmann and Metz 2017). In their paper on comparative leadership styles, and drawing on some of their earlier works in managing organizations in Africa, Blunt and Jones (1997) made an early call to not underestimate the risks of neo-colonialism and acknowledge the limits of leadership theories originated in the global West when applied to emerging contexts, including Africa (cf. also Nkomo 2011; Smith 2013). While Ubuntu is not explicitly mentioned by Blunt and Jones, they do highlight how leadership in Africa is characterized by “the importance of family and kin networks (… and that) social networks (are) crucial to provide individual security” (1997, Table 1, p. 19). Drawing on the elements reviewed in the preceding paragraphs, we shall now attempt to derive implications for rethinking ethical relational leadership from this perspective.

Swanson (2007) conceptualizes Ubuntu as a collectivist philosophy, linking affective, relational and moral elements in the idea of ‘humble togetherness’, particularly applied in a pedagogical context. This proposal can directly contribute to leadership conceptualized not as strength and other highly masculine stereotypes, but as humility, and the relationality of levels that bind an individual to others, linking it to the pursuit of the idea of the ‘common good’ on a global scale (Lutz 2009; Tavernaro-Haidarian 2018). From this perspective, leadership is built around the idea of relatedness, and harmony between leaders and followers in a constant process of learning-by doing (Hoffmann and Metz 2017; Tavernaro-Haidarian 2018).

Four Principles of Ethical Relational Leadership from an African Perspective

Aiming to build on such works, and believing in the value of bringing such insights to a broader audience, we shall now take this opportunity to expand present theorizing on relational ethical leadership. We outline what we view as four potential principles of ethical relational leadership, this time from an African perspective: interdependence, relational normativity, communality and understanding unethical leadership essentially as a failure to relate.

(1) Interdependence The fulfilment of the self (the leader) is understood as interdependent with the care and welfare of others. The Ubuntu world view “I am because we are” is relational, and thus the Ubuntu ethic would situate the core of ethical leadership and the freedom of individual leaders as being bound up interdependently with others (Hoffmann and Metz 2017). The ethical value of leadership within this frame of thought is rooted in relationships between people, rather than just the individual:

“An Ubuntu ethic is unambiguous about freedom: it is in large part a form of interdependence with others, a kind of ‘freedom to’ relate in a certain way that is distinct from the negative liberty of ‘freedom from’ the interference of others” (Hoffmann and Metz 2017, p. 158).

(2) Relational normativity An African perspective on ethical relational leadership has a normative element. In defining humanity or humanness as a bind to others and a drive towards restoration and peace, it carries an inescapable normative imperative: “Ubuntu as a concept that epitomizes humanness is ever seeking restoration, healing, peace and life to all” (Kgatla 2016). Furthermore, this imperative also explicitly addresses issues about inequality that remain pervasive in the African context (Murove 2014). Material inequality then appears as an implicit element of relationality, which mirrors the normative aspect of Ubuntu to strive for the betterment not only of the self, but of the world that self is bound to.

(3) Communality is central. Community relationship is valued for its own sake. It is about social network and ties, rather than a defined community, it is a communal relationship of fellowship and harmony (Metz 2014). This communality is about relationality and interdependence that places communal interests above individual interests (McDonald 2010). Here too, the various levels can connect to make ethical leadership engage relationally between the self and the community embedded in mutual relationships of fellowship and harmony.

(4) Unethical leadership as a failure to relate Reflecting on relationships at the heart of morality and justice in the Ubuntu ethic, Hoffmann and Metz (2017) summarize this as “wrongdoing is essentially a failure to relate”, the fact of being closed to others and the world, what others have called ethical blindness or myopia. This fourth dimension complements the prior three by adding a negative definition to what ethical relational leadership is not under this theoretical framework.

In order to make these ideas more concrete, we shall now unpack how this theoretical framework can be deployed in practice and translated effectively into action and ethical leadership development, rooted in an African-inspired relationality.

How the VDLA Course Unpacks Relational Ethical Leadership

Genesis and Aims of the VDLA

The Values-Driven Leadership in Action (VDLA) executive course was developed as part of the third author’s role in facilitating the design of an executive development course on behalf of an international NGO, as a service to African Business Schools. Three of the corporate members of this NGO (company X, X and X, not disclosed here for blind review) identified talent development in Africa as a major priority. Together they sponsored a curriculum development workshop in December 2015, the initial pilot phases (2016–2017), train-the-trainer courses (2017 and 2018), and an on-going quality-assurance process. Through a process of co-creation with faculty members from eight African business schools, a draft curriculum for an executive development course on ethical African leadership evolved. Mary Gentile was part of the initial curriculum development workshop, sharing her GVV approach with participants, and facilitating discussion about its relevance in the African context. In the meantime, various international grants have been sought to continue the programme and fulfil its mission, which is to “build leadership capacity for ethical and sustainable business on the African continent” (programme description).

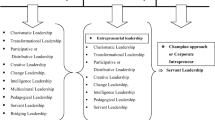

Relying on a series of theoretical tools drawing on various philosophical traditions and ongoing reiteration in practice, the course has evolved into a unique integrative design to help participants put values-driven leadership into action. One of its key components is what is called the ME-WE-WORLD framework (see Fig. 1). As far as we know, no scholarly rationale has been presented for this multi-level integrative ME-WE-WORLD framework, although this terminology has been used in the past by large corporations, such as the Coca-Cola Company when discussing sustainability and social value (Perez 2012; ECCBC 2018). We believe that a more rigorous conceptualization of this ME-WE-WORLD framework, based on how it is used in practice (in particular through the dream-board exercise explained hereafter), will not only strengthen its application, but also allow us to use it as a critical tool to reflect on corporate practice and inform contextually relevant approaches to values-driven business on the African continent. It is important to stress that ‘Africa’ should not be treated as a homogenous whole (cf. Nkomo 2011), and that its rich diversity of traditions should be reflected in the various iterations of the course as it is employed in different contexts.

The employment of this ME-WE-WORLD framework occurred spontaneously as part of the evolving curriculum with African faculty suggesting it as a helpful model to frame training on leading ethical and sustainable businesses on the continent. Other experiential learning exercises were also identified, as is described elsewhere (references removed for blind review). For the purposes of this paper, we would specifically like to develop the ME-WE-WORLD ‘dream-board’ exercise by articulating its theoretical assumptions in and through a reflection on its employment in practice.

Theorizing from the Dream-Board Exercise

To be clear, it is important to acknowledge that the practice of using the dream-board came first, and the theoretical reflection that we offer here, after the fact. It was during the third pilot of the course material in Egypt that the facilitator (one of the authors) intuited that it could be helpful to create a ‘dream-board’ for the group to articulate and name their hopes and dreams on three levels: individual (ME), organizational (WE) and country (WORLD). As mentioned by Smith (2013, p. 214), “naming the world” is important and performative. Where this intuition came from, the facilitator can only explain in retrospect. Having run two pilots at that stage, she felt that a more experiential and interactive approach was needed to make the ME-WE-WORLD framework more meaningful to participants. An important factor may also have been the challenge of sustaining group energy and attention after lunch on the first day of the training. Her goal was to engage the participants on an affective level and trigger positive aspirations within the group, rather than merely focusing on Africa’s problems. Again, echoing Smith’s insights for decolonizing methodologies and research: “In all community approaches, process- that is methodology and method- is important. In many projects, process is far more important than the outcome. Processes are expected to be respectful, to enable people, to heal and to educate" (2013, p. 218). Since she has always used anonymous post-it notes to great effect to animate confidential group participation, she improvised the dream-board exercise on the spot.

She drew three concentric circles on a white-board (see Fig. 2), with ME being the inner circle, and the organization and the world in expanding circles around it. Each participant was then given three post-it notes and asked to use these to anonymously write down three dreams, i.e. one for her/him as individual, one for his/her organization, and one for the ‘world’, here defined as their own country, i.e. Egypt. This exercise was also conducted a year later in Kenya (Fig. 3). By articulating their dreams, participants locate themselves (ME) within a network of relationships including personal and professional ones (WE), and more broadly (WORLD) (see Figs. 1, 2, and 3). None of the subjective (ME) level issues can be disconnected from the other two, meaning that they are always relationally constructed and experienced.

In what follows, we highlight some of the emerging insights regarding the role of relationality in ethical leadership that emerged from the dream-board exercise, reflecting on both African and European philosophical perspectives (Table 1 summarizes the themes arising from the dream-board exercise). We follow our four principles of ethical relational leadership derived from our review of Ubuntu outlined in the previous section.

(1) Interdependence In the dream-board exercise, at the individual level, each participant conceptualizes herself or himself in the sense that they ‘dream for themselves’. These dreams were often intensely personal, but even as such, dreams of “contentment”, making “positive change” or having “positive impact” and “peaceful” relationships indicate a desire for harmony with others and one’s environment.Footnote 1 More specifically, service to others, especially to younger generations, and dreams related to leading transformational societal change were prominent. The relational ontology of the self that is operative here certainly reflects some of the poststructuralist insights discussed above, but we believe that the African notion of Ubuntu may offer another conceptual angle to understand the agency of values-driven leaders on the African continent. Reflecting on some of the key principles of Ubuntu may help us gain more depth in understanding the capacities for moral agency that African leaders possess. From this perspective, the details of lives in relation to others lie at the heart of moral agency. As outlined by Metz (2014) and more recently Hoffmann and Metz 2017) they prize relationships to the point that they seek to sustain them by closely linking very personal aspects, elements of one’s history, self-understandings, one’s aspirations as well as one’s fears, and understanding the sharing of these as the basis for more harmonious relationships.

(2) Relational normativity The African approach to ethics is neither particularly principled, nor prescriptive. Hoffmann and Metz go as far as stating that no “prominent African thinker seeks to offer an algorithm by which to apply ethical values and principles” (2017, p. 158). Reflecting Mary Gentile’s GVV approach, the normativity that guides action is relationally defined, with a sense of ‘how can we get the right thing done’? What we see emerging from the dream-boards is not dreams of ‘freedom from’ (someone or something), but rather the desire for harmonious interdependence. The way in which individual interest is reframed in terms of being ‘bound-up’ with groups is central to Ubuntu philosophy. However, this desire for harmonious interdependence does not rule out the presence of factors such as the importance of competitiveness, excellence and on-going innovation in organizational contexts that may pit individuals and groups against one another. This duality was evident in the dream-board exercise with participants dreams for their organization’s related to both care and societal impact, intertwined with dreams of being a “catalyst for change”, the “Best in class/leader of industry” and being a “centre of excellence for Africa”.

Many of the practices taking place at the organizational level tend to disrupt relationality, for instance by encouraging competitive behaviours in individual incentive plans. This creates certain ethical challenges that the training can highlight, particularly the gaps between the various levels represented in ME-WE-WORLD. From the perspective of Ubuntu philosophy, organizing and competing can be framed in more humanitarian notions of relationality which can bring a different ethos to Western priorities of utility, autonomy and capability (Metz 2014). The Ubuntu ethic of prizing relationships draws attention to individual’s histories, self-understandings and aspirations in a normative sense, because this provides the basis for seeking insight on how relations can be more harmonious or less conflictual (Metz 2014).

Rethinking these organizational values from a relational point of view emerges as an important imperative. The content of the dream-boards echoes Painter-Morland’s (2007) argument that relational responsiveness allows us to argue that organizations should not only be concerned with accountability for past mistakes or future disasters, but to proactively be accountable towards various stakeholders. Somewhat echoing what Woermann and Engelbrecht (2017) call the Ubuntu challenge to business, i.e. to conceive stakeholders as “relation holders”. The challenge may indeed be to reframe the organizational discourse from a relational perspective to be more in line with the dreams that exist on individual level, and in terms of societal needs. Currently, the way in which organizations function and the terminology that they use often denies or underemphasizes relationality.

(3) Communality The VDLA course seeks to empower African leaders to solve complex ethical dilemmas in society. A sense of community and complex dilemmas was present at all levels of the ME-WE-WORLD framework in the dream-board exercises. This was reflected in dreams at the individual level to serve and care for the community, but the organization was also seen as a potential agent of transformation, with dreams such as “Catalyst of positive change”, “become an academy for youth empowerment”, “be a centre of excellence for Africa”, and “Impactful solutions in the health sector”. Themes around tolerance, equality, acceptance, and opportunities for all reflected the Ubuntu ethic of communal harmony in dreams for society as a whole.

By drawing on community relationality, partnerships and systemic levers for change can be identified at the individual, organizational and societal levels. In the VDLA these ‘levers for change’ are presented as a ‘Toolkit for moral practice’ and incorporate various tools ranging from listening skills in an organizational setting, to external tools such as reporting and transparency mechanisms. This approach reflects an Ubuntu ideal of non-competitive consensual models of decision-making and agreement for change. Rather than make the individual the sole agent, the approach that is suggested is systemic and ‘communal’ in nature. An Ubuntu ethic favours “dialog and public deliberation in order to determine the right way forward”, and resolutions to complex dilemmas are dependent on communal discourse and deliberation, as opposed to solitary reflection (Hoffmann and Metz 2017, p. 158). Consequently, an Ubuntu based framing of the organization as a community in relation to other communities challenges the ethic of competition and success by giving space for the consideration of how an organization may contribute to the pursuit of greater equality or unity.

(4) Unethical leadership as the failure to relate From the perspective of African philosophy, unethical leadership emerges when one’s connection to others are severed through individualist behaviour and personal greed, many examples of which unfortunately exist across the continent. Western consumerism and growth aspirations have created materialist ambitions and competitive attitudes that seem to be perpetuated by corporate rhetoric around competitiveness, innovation and profit margins within organizations. Results from the Global Survey on Business Ethics showed that the overarching theme for Sub-Saharan Africa was ‘ethical management and leadership’, with ‘corporate governance’, ‘ethics management’ and ‘the prevention of corruption and corporate misconduct’ the most popular areas of focus for teaching and training (Rossouw 2011, p. 88). Could it be that corporate values are in need of a relational overhaul?

The VDLA seeks to empower African leaders to confront such challenges, and aspires to transformational change in individuals, their organizations and society. This was particularly evident in the dream-board in the WORLD (COUNTRY) dimension:

“No discrimination on the basis of race, gender; nationality for refugees and stateless persons”;

“Peace through good accountability of governments; transparency for government performance”;

“To become a country where resources are equitably distributed through governance, accountability and transparency”;

“I dream of a country that feeds [and] protects its citizens while allowing them to fully explore their human potential”.

From an Ubuntu perspective the unethical failure to relate, conversely suggests that relationality can challenge systemic ethical failures such as corruption and mismanagement. This has significant implications for ethical leadership theory and development.

VDLA in Practice

The dream-board demonstrates the applicability of relationality and Ubuntu in a practical setting, involving African leaders from business, government and non-profits. However, it is also appropriate to note resultant impacts in practice among VDLA participants. This is something we have been able to track due to the establishment of the Research on Ethical African Leadership Network (REAL-Network) in May 2018. The REAL-Network was established for the explicit purpose of (a) sustaining VDLA engagement (e.g.: through monthly video calls), and (b) to track ongoing application of VDLA. Not all VDLA alumni choose to engage with the REAL-Network, but Table 2 highlights the case of six VDLA participants who have stayed engaged and have gone on to use the VDLA in various ways.Footnote 2

Four VDLA alumni delivered bespoke VDLA training either within their organization or to target groups within their community or sector. One small business owner began the process of preparing a tender for delivering VDLA workshops to several government departments, and one academic was able to gain funding as a result of connections with VDLA participants from other countries, forged via the REAL-Network.

In November 2018, we asked REAL-Network members whether engagement with particularly ‘problematic’ stakeholders was more likely, less likely or remained the same as a result of their attendance at a VDLA course. They were also asked to reflect on why they answered as they did. Out of 18 respondents, three did not answer the question, one stated: “remained the same” and the remaining 14 stated “more likely”. Reasons given included “Yes, because of interaction and the nurturing of trust” [Respondent (R) 18]; “I believe after the course I started to think differently that we can always live our values and that it is not a question of the ‘what’ but the ‘how’” [R4]; “understand the more likely motivation of other stakeholders” [R11]. Many of the reasons given highlight the primacy of aspects of relationality to overcome challenges in engaging with other stakeholders. For example, one respondent stated “Values driven leadership amongst other seeks to come out with business solutions that can take into account interests of others” [R16]. Whilst anecdotal, this further illustrates the value of African perspectives on relationality which situates a failure to relate as a core feature of unethical leadership.

The dream-board illustrates how VDLA participants can locate themselves and their dreams for their organization and their world in the ME-WE-WORLD framework during a training programme. Similarly, we see how VDLA alumni demonstrate further engagement with the ME-WE-WORLD framework at various levels. In relation to the ME for example, by becoming certified VDLA trainers, by seeking to empower others (WE) with VDLA principles and citing aspects of relationality as central to engaging with difficult stakeholders (WE) and/or (THE WORLD). Our reflection on this VDLA exercise demonstrates how the amalgamation of Western and African conceptions of leadership development can identify principles for values driven leadership in action: interdependence; relational normativity; communality, and the framing of unethical leadership as the failure to relate. The theoretical and practical implications for ethical leadership theory and development are considered in the remainder of this paper.

Discussion and Contributions to Ethical Leadership Theory and Development

Our paper presents an empirically illustrated theoretical proposal for rethinking ethical relational leadership from an African perspective. This has been identified as a key area for developing business ethics training in African settings (Ike 2011; Rossouw 2011; Smit 2013), particularly in the face of numerous critiques on the impact of business ethics education in fostering moral development (Catacutan 2013).

In doing so, we have strived to address two shortcomings. First, the fact that Western scholars have often treated non-Western epistemologies, ontologies and experimentations as marginal. Such a Western bias has largely contributed to an epistemic domination, long denounced by post-colonial theorists. In contexts such as Africa, including other voices and developing management education programmes rooted in local ontological and epistemological sensibilities can help fight the risk of epistemic coloniality (Ibarra-Colado 2006; Murphy and Zhu 2012). Such initiatives, being theoretically and methodologically informed from the South, become “a significant site of struggle between the interests and the ways of knowing of the West, and the interests and ways of resisting of the other” (Smith 2013, p. 31). Furthermore, such programmes can help spread their contributions in the reverse direction, from South to North, further challenging many of the underlying assumptions that undermine taking ethical concerns seriously and effectively in management education (Nkomo 2011; Painter-Morland 2015). Second, while some notable exceptions discussed earlier in this paper do exist, they often offered theoretical or philosophical discussions of Ubuntu, while nevertheless lacking actionable guidelines to translate its principles into concrete managerial and leadership practice.

This paper responds to these two issues, firstly by establishing a theoretical dialogue among both traditions and proposing an African-rooted contribution to relational ethical leadership theory, and secondly by showing how this can effectively be put into practice through a pedagogical design of the VDLA. In fact, instead of one-directionally ‘applying’ certain theoretical ideas, the practice of experiential learning methods that draw on relational techniques enabled us to articulate the potential theoretical conversation between Western and African ontologies. As such, it allowed us to reveal an intimate interaction between theory and practice in a way that defies the binaries which still plague ‘applied philosophy’.

We shall now discuss some of the most relevant contributions and outline some avenues for pursuing this line of research. Most importantly, we believe our proposed theoretical framework as illustrated by the VDLA course offers interesting insights to pursuing ethical relational leadership theory, this time from an African perspective. Thus, we add to emerging attempts to make connections between African philosophies such as Ubuntu and global management theory and leadership (e.g. Lutz 2009; Prozesky 2009). While relational leadership (Uhl-Bien 2006; Cunliffe 2009) continues to develop, both in general leadership studies (Cunliffe and Eriksen 2011), and in ethical and critical leadership studies (Maak and Pless 2006; Liu 2017; Rhodes and Badham 2018), relationality is a core feature. We believe that everyday practice in the African context precedes much of this theorization. We have attempted to show how its insights can help overcome some of the dichotomies of Western ontologies (mind/body, me/you) by offering a stronger relational reading, thereby more closely knitting together the subjective, intersubjective and collective levels, by means of the exercises playing out on the different ME-WE-WORLD levels.

Some leadership scholars have offered important insights into the way leaders provide direction in organizations. Instead of unilaterally ‘directing’ the behaviours of others, ‘enabling’ leadership entails disrupting existing patterns, encouraging novelty and then making sense of whatever unfolds (Plowman et al. 2007, p. 342). As a counteracting force, a basic life goal of African philosophy and Ubuntu is to realize human excellence, through community and honouring harmonious relationships (Metz 2014). We suggest that Ubuntu challenges the unethical failure to relate by calling leaders in a relational-normative sense to see oneself as an integral part of the whole, working to achieve the good of all, pursuing cooperative creation and distribution of wealth (Metz (2014), drawing on the Nigerian philosopher Segun Gbadegesin and the Kenyan philosopher Professor D. A. Masolo).

Furthermore, the dream-board statements presented in the previous section could easily be dismissed as fanciful and seemingly unattainable when confronted with systemic challenges such as inequality, exclusion, discrimination, corruption and unaccountable power. Yet, the importance of service to others that emerges from the dream-board also flies in the face of many Western ‘strong-man’ conceptions of leadership. It parallels what European scholars have recently termed ‘weak management’, which is characterized by hospitality, fragility and putting the ‘Other’ at the heart of management (Deslandes 2018). From a leadership development perspective, the VDLA course is, in a very concrete manner (e.g. through experiential exercises such as the dream-board), creating a relational space where relationality can unfold. This relationality has agency, which shapes everyone and everything in its ambit. From this perspective, relational accountability becomes key to the process by which responsible and sustainable business practices emerge (Painter-Morland 2007, 2008a, b, 2012; Painter-Morland and Deslandes 2015). If this process of relational accountability fails, we may also argue that it is a result of impoverished or corrupted relational space. The space of the VDLA course itself is a space for relational engagement for facilitators as well. As detailed above, the dream-board exercise and other elements have emerged as embodied improvisations, because on the one hand the safe communal space was created to allow for such improvisations and engagement on a personal level by the facilitator. On the other, the main objective was precisely to maintain the relationality among the group, an aspect that we suggest is central to empowering values-driven leadership in action.

More broadly, we have sought to contribute to the business ethics as practice perspective (Clegg et al. 2007; Painter-Morland 2008b), by focusing on the practicality of implementing values-driven leadership. Rhodes and Badham (2018) recently concluded that ethical irony is one way of approaching this. We suggest that VDLA is an alternative approach which maybe more directly ‘applicable’ in the sense that it infuses relationality into each of the steps of the course. Moreover in an African context, it provides an overarching theoretical framework that integrates inputs both from Western and African traditions. Namely, Mary Gentile’s Giving voice to values (GVV) is woven into the VDLA course in a unique way. The basic GVV premise, which has found rather positive echoes among African participants on the VDLA course, is that “most people want to bring their whole selves to work and therefore to act on their values” (Gentile 2011, p. 306, emphasis in original). This holistic, rather than compartmentalized view of the self is a key component for fostering relationality, yet it is often undermined by Western injunctions of ‘leaving one’s ethics at the door’ when entering the workplace, a point which is often instilled very early in management education (Giacalone and Promislo 2013).

The dream-board constitutes a first springboard to dream different, to imagine alternative states of the world, in order to then be able to re-script our own rationalizations of why the world is as it is, and seemingly cannot be changed. On a more political level, Ubuntu philosophy emphasizes inclusive deliberation, rather than ‘power over’ (Tavernaro-Haidarian 2018, pp. 27, 35), and by adopting a critical perspective (in a political sense, such as that advocated by Praeg 2017), Ubuntu can be a vehicle for questioning the relations of power that systematically exclude people (Stacy 2015). For Metz (2014) the value in this approach lies in what Ubuntu can contribute to debates on the ideal distribution of political power, both nationally and internationally in mechanisms such as the United Nations. In a consideration of what a progressive form of Ubuntu socialism might bring to society, McDonald (2010) suggests that whilst small Ubuntu-inspired victories can contribute to change, a more comprehensive vision of transformation is required, with democratic, consultative processes of change from above and below. Such inclusive notions of power and relationality have significant implications for the promotion of values-driven leadership that contributes to transformational societal change in Africa and beyond.

The ME-WE-WORLD framework provides a way of directly addressing Giacalone and Thomson’s (2006) critique of how business school curricula tends to promote an organization-centred worldview and its profit interests, instead of a human-centred worldview. Our proposed theoretical framework fosters concern for an interconnectedness, or ‘togetherness’ (Swanson 2007) of the different levels, thereby challenging the organization-centeredness of mainstream management education. The organization is still there, and as the figures above illustrate, it remains a key player, but it is viewed as part of a holistic system, amidst other stakeholders (Brinkman and Sims 2001). Such a shift away from an organization-centric perspective, Giacalone and Thomson (2006) argue, could help integrate a vision of the self (identification) and a view of others and the world (inspiration) that triggers their motivation.

Additionally, let us not forget that identification and inspiration are two of the key elements of leadership. It is in this regard that our analysis offers insights that could deepen and extend our understanding of post-heroic approaches to leadership such as transformational leadership (Burns 1978; Bass 1990; Bass and Riggio 2006; McCleskey 2014). Some applications of transformational leadership have been criticized as narrow and managerialist, and often ineffective because it fails to take account of systemic pressures (Currie and Lockett 2007). Our analysis would suggest that its failure may lie in its continuing reliance of individualist assumptions, i.e. a central, strong individual lies at the heart of the ‘transformation’ that takes place in organizations and in the lives of followers. Embracing a more radically defined relational ontology would allow one to view ‘leading’ as a relational response that requires systemic change and fundamentally shift the focus away from individual leaders towards understanding relational dynamics.

Conclusion

We set out to show how theorizing relationality from the African philosophical tradition of Ubuntu can bring new insights to Western philosophical perspectives on relationality in the context of ethical leadership development. We have presented an African-rooted contribution to relational ethical leadership theory and demonstrated how this can effectively be put into practice through a particular pedagogical design of the VDLA. Consequently, this paper provides an important African contribution, which can help counteract the dominance of Western philosophical conceptions in leadership development literature, in particular its individualist and organization-centeredness. There are of course limitations to our contribution, our theorizing on African-inspired relationality draws on one particular example of an Ubuntu-inspired leadership course. Nonetheless, the centrality of Ubuntu-inspired notions of interdependence, normative relationality, and communality brings a fresh perspective, particularly when unethical leadership is framed as the failure to relate. This demonstrates firstly, how values-driven leadership discourse can be reframed from a relational perspective in a way that is more in line with the dreams that exist on the individual level for ourselves, our organization and our society. Secondly, we have also shown how the practice of embodied experiential learning through programmes such as the VDLA, can provide a space for vocalizing relational aspirations as a catalyst for values-driven leadership in action. In the process, examples and useful exercises emerged that highlight how practicing Ubuntu could transform the way in which leadership development takes place. As a basic tenet of African philosophy and ethics, Ubuntu suggests that a basic life goal should be to realize human excellence, which can only be done if living communally with others, honouring harmonious relationships (Metz 2014).

Much remains to be done to establish the both the theoretical and societal impact of Ubuntu-inspired relational practices in terms of preventing unethical behaviour in various contexts. It is in this regard that our study is only the first step in articulating the relationship between Western and African ontologies from a theoretical perspective. A more fine-grained conceptual analysis of the points of divergence and overlap would be required. In terms of studying the impact of Ubuntu-inspired leadership development in practice, a lot more data will need to be gathered in various contexts. The fact that up to now the VDLA has been focused on small-group experiential learning, limits the numbers of respondents to our ongoing investigations on impact. There are however plans to scale the programme, also by means of digitalization, which would potentially allow us to add quantitative data to what at this stage is limited to qualitative assessments of impact.

What seems clear, is that it is surely time for African notions of relationality to be more central in our theorizing and practical outworking of values-driven leadership, by bringing the whole self to the workplace and developing ethical relational—and holistic—forms of leadership. Further interdisciplinary research might explore the interdependencies and mutually enriching aspects of both Western and African traditions, drawing on anthropological and sociological insights, as well as perspectives from behavioural economics, to develop a nuanced understanding of agency. It would also be important to explore how this African perspective connects to other voices from the South and other emerging economies, in order to understand how relational forms of leadership may foster more sustainable business models that serve social interests. Fostering relational accountability among our leaders in the way we develop management education may be the key to finding new ways of approaching the purpose of business as such.

Notes

We should however also acknowledge that “retiring rich by a seashore” was also mentioned!

In each cohort of 15–20 participants, around 10% have remained particularly active, pursuing their engagement by becoming certified trainers and/or by organizing workshops with VDLA methodologies within their own organizations. The six mentioned in Table 2 belong to this top 10%.

References

Alcadipani, R., Khan, F., Gantman, E., & Nkomo, S. (2012). Southern voices in management and organization knowledge. Organization,19(2), 131–143.

Arce, D. G., & Gentile, M. (2015). Giving voice to values as a leverage point in business ethics education. Journal of Business Ethics,131, 535–542.

Bakken, T., Holt, R., & Zundel, M. (2013). Time and play in management practice: An investigation through the philosophies of McTaggart and Heidegger. Scandinavian Journal of Management,29(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2012.09.003.

Bass, B. M. (1990). From transactional to transformational leadership: Learning to share the vision. Organizational Dynamics,18(3), 19–31.

Bass, B. M., & Riggio, R. E. (2006). Transformational leadership (2nd ed.). New York: Psychology Press.

Bevan, D., & Corvellec, H. (2007). The impossibility of corporate ethics: For a Levinasian approach to management ethics. Business Ethics: A European Review,16(3), 208–219.

Blankenberg, N. (1999). In search of real freedom: Ubuntu and the media. Critical Arts,12(2), 42–65.

Blok, V. (2014). Being-in-the-world as being-in-nature: An ecological perspective on being and time. Studia Phaenomenologica,14, 215–235.

Blom, M., & Alvesson, M. (2015). All-inclusive and all good: The hegemonic ambiguity of leadership. Scandinavian Journal of Management,31(4), 480–492.

Blunt, P., & Jones, M. L. (1997). Exploring the limits of western leadership theory in East Asia and Africa. Personnel Review,26(1/2), 6–23.

Bouilloud, J., & Deslandes, G. (2015). The aesthetics of leadership: Beau geste as critical behaviour. Organization Studies,36(8), 1095–1114.

Brinkman, J., & Sims, R. R. (2001). Stakeholder-sensitive business ethics teaching. Teaching Business Ethics,5(2), 171–193.

Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. New York: HarperCollins.

Byers, D., & Rhodes, C. (2007). Ethics, alterity, and organizational justice. Business Ethics: A European Review,16(3), 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8608.2007.00496.x.

Catacutan, R. (2013). Education in virtues as goal of business ethics instruction. African Journal of Business Ethics,7(2), 62–67.

Chilisa, B. (2012). Indigenous research methodologies. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Clegg, S. R., Kornberger, M., & Rhodes, C. (2007). Business ethics as practice. British Journal of Management,18(2), 107S122.

Collinson, D. (2005). Dialectics of leadership. Human Relations,58(11), 1419–1442.

Collinson, D. (2014). Dichotomies, dialectics and dilemmas: New directions for critical leadership studies? Leadership,10(1), 36–55.

Cooper, R. (2005). Peripheral vision: Relationality. Organization Studies,26(11), 1689–1710.

Crevani, L., Lindgren, M., & Packendorff, J. (2010). Leadership, not leaders: On the study of leadership as practices and interactions. Scandinavian Journal of Management,26(1), 77–86.

Cunliffe, A. L. (2009). The philosopher leader: On relationalism, ethics and reflexivity—A critical perspective to teaching leadership. Management Learning,40(1), 87–101.

Cunliffe, A., & Eriksen, M. (2011). Relational leadership. Human Relations,64, 1425–1449.

Currie, G., & Lockett, A. (2007). A critique of transformational leadership: Moral, professional and contingent dimensions of leadership within public services organizations. Human Relations,60(2), 341–370.

Deslandes, G. (2011a). Indirect communication and business ethics: Kierkegaardian perspectives. Business and Professional Ethics Journal,30(3), 307–330.

Deslandes, G. (2011b). In search of individual responsibility: The dark side of organizations in the light of Jansenist ethics. Journal of Business Ethics,101, 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1173-6.

Deslandes, G. (2012). Power, profits, and practical wisdom: Ricoeur’s perspectives on the possibility of ethics in institutions. Business and Professional Ethics Journal,31(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.5840/bpej20123111.

Deslandes, G. (2018). Weak theology and organization studies. Organization Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840618789209.

ECCBC. (2018). ‘ME WE WORLD—Sustainability—ECCBC’. Retrieved August 30, 2018 from http://www.eccbc.com/en/sustainability/me-we-world.

Fairhurst, G. T., & Uhl-Bien, M. (2012). Organizational discourse analysis (ODA): Examining leadership as a relational process. Leadership Quarterly,23(6), 1043–1062.

Faÿ, E., Introna, L., & Puyou, F. R. (2010). Living with numbers: Accounting for subjectivity in/with management accounting systems. Information and Organization,20(1), 21–43.

Faÿ, E., & Riot, P. (2007). Phenomenological approaches to work, life and responsibility. Society and Business Review,2(2), 145–152.

Gentile, M. (2010). Giving voice to values: How to speak your mind when you know what’s right. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Gentile, M. (2011). A faculty forum on giving voice to values: Faculty perspectives on the uses of this pedagogy and curriculum for values-driven leadership. Journal of Business Ethics Education,8, 305–307.

Gentile, M. C. (2012). Values-driven leadership development: Where we have been and where we could go. Organization Management Journal,9(3), 188–196.

Gentile, M. (2013). Educating for values-driven leadership: Giving voice to values across the curriculum. NY: Business Expert Press.

George, G., Corbishley, C., Khayesi, J., Haas, M., & Tihanyi, L. (2016). Bringing Africa in: Promising directions for management research. Academy of Management Journal,59(2), 377–393.

Giacalone, R. A., & Promislo, M. D. (2013). Broken when entering: The stigmatization of goodness and business ethics education. Academy of Management Learning and Education,12(1), 86–101.

Giacalone, R. A., & Thomson, K. R. (2006). Business ethics and social responsibility education, shifting the worldview. Academy of Management Learning and Education,5(3), 266–277.

Goduka, I. N. (2000). Indigenous/African philosophies: Legitimizing spirituality centred wisdoms within academy. In P. Higgs, N. Vakalisa, T. Mda, & N. Assie-Lumumba (Eds.), African voices in education. Landsdowne: Juta and Co Ltd.

Grint, K. (2010). The sacred in leadership: Separation, sacrifice and silence. Organization Studies,31, 89–107.

Hoffmann, N., & Metz, T. (2017). What can the capabilities approach learn from an ubuntu ethic? A relational approach to development theory. World Development,97, 153–164.

Ibarra-Colado, E. (2006). Organization studies and epistemic coloniality in Latin America: Thinking otherness from the margins. Organization,13(4), 463–488.

Ibarra-Colado, E., Clegg, S. R., Rhodes, C., & Kornberger, M. (2006). The ethics of managerial subjectivity. Journal of Business Ethics,64(1), 45–55.

Ike, O. (2011). Business ethics as a field of teaching, training and research in West Africa. African Journal of Business Ethics,5, 89–95.

Jones, C., (Ed.). (2007). Special issue: Levinas, business, ethics. Business Ethics: A European Review 16(3), 196–321.

Jones, C., Parker, M., & Ten Bos, R. (2006). For business ethics. Abingdon: Routledge.

Kagabo, L. (2011). Business ethics as field of training, teaching and research in francophone Africa. African Journal of Business Ethics,5(2), 74–80.

Kgatla, S. T. (2016). Relationships are building blocks to social justice: Cases of biblical justice and African Ubuntu. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies,72(1), a3239. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v72i1.3239.

Khoza, R. (2006). Let Africa lead: African Transformational leadership for 21st century business. Johannesburg: Vesubuntu Publishing.

Kolk, A., & Rivera-Santos, M. (2016). The State of research on Africa in business and management: Insights from a systematic review of key international journals. Business and Society,56(7), 1–22.

Kupers, W. M. (2013). Embodied inter-practices of leadership. Leadership,9, 335–357.

Ladkin, D. (2006). When deontology and utilitarianism aren’t enough: How Heidegger’s notion of ‘dwelling’ might help organisational leaders resolve ethical issues. Journal of Business Ethics,65(1), 87–98.

Ladkin, D. (2012). Perception, reversibility, “flesh”: Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology and leadership as embodied practice. Integral Leadership Review,12(1), 1–13.

Liu, H. (2017). Reimagining ethical leadership as a relational, contextual and political practice. Leadership,13(3), 343–367.

Louw, D. J. (2010). Power sharing and the challenge of ubuntu ethics. paper presented at the forum for religious dialogue symposium of the research institute for theology and religion at the University of South Africa, January 2010, Pretoria, South Africa.

Lutz, D. (2009). African Ubuntu philosophy and global management. Journal of Business Ethics,84(3), 313–328.

Maak, T., & Pless, N. M. (2006). Responsible leadership in a stakeholder society: A relational perspective. Journal of Business Ethics,66, 99–115.