Abstract

Companies are expected to monitor sustainable behaviour to help improve performance, enhance reputation and increase chances of survival. This paper examines the relationship between sustainability committees and independent external assurance on the inclusion of sustainability-related targets in CEO compensation contracts. Using a sample of UK FTSE350 companies for 2011–2015 and controlling for governance and firm characteristics, we find both board-level sustainability committees and sustainability reporting assurance have a positive and significant association with the inclusion of sustainability terms in compensation contracts. However, there is no joint impact between the voluntary use of independent external assurance and the role of sustainability committees on CEO compensation contracts. Sustainability-related terms in compensation contracts are more likely to be included, and higher compensation is likely to be paid, when assurance is provided by a Big4 firm and when a company operates in a sustainability-sensitive industry. Our findings highlight the potential of assured sustainability reports in assessing CEO performance in sustainability-related tasks, especially when sustainability metrics are included in CEO compensation contracts. Overall, our results suggest companies that invest in voluntary assurance are more likely to monitor management’s behaviour and be concerned about the achievement of sustainability goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is an increased emphasis on incentivising and rewarding management for the achievement of social goals. Companies concerned about sustainability are likely to link executive compensation to sustainability in recognition of the view that management needs to be compensated for the increased risks associated with long-term social strategies (Frye et al. 2006; Berrone and Gomez-Mejia 2009b; Eccles et al. 2014). Indeed, some companies are linking sustainability performance to CEO compensation and recognising that if they connect sustainability performance and compensation, they can become models for their peers particularly because sustainability reporting is evolving and investors are increasingly identifying the business value of sustainability performance (Tonello and Singer 2015). An E&Y (2010) report, for example, provides a summary of the major issues CEOs and boards of directors should discuss when considering sustainability reporting. In a question related to what governance systems and processes are needed to report on sustainability, it indicates that some organisations link sustainability performance to executive compensation in order to sharpen their focus on sustainability issues.

This paper extends studies examining social performance as a determinant of CEO pay (e.g. Riahi-Belkaoui 1992; Cordeiro and Sarkis 2008; Cai et al. 2011; Francoeur et al. 2017) and focuses on the impact of sustainability assurance and the existence of board-level sustainability committees on CEO compensation. The voluntary external assurance of sustainability reports can enhance their reliability and credibility and mitigate management camouflaging sustainability issues (Bebchuk and Fried 2003; Brown-Liburd and Zamora 2014; Cohen and Simnett 2014; Eccles et al. 2014; Wong and Millington 2014).Footnote 1 Prior literature provides mixed evidence on the relationship between executive compensation and social performance and is mainly based on cross-country data or US settings. There is limited research on the effect of firm investments in sustainability on executive performance. Berrone and Gomez-Mejia (2009b) call for external monitoring mechanisms such as external audit to assess the credibility of sustainability information and note that if CEOs are not compensated for the increased risks associated with social investments, they may seek less risky short-term alternatives. Additionally, the existence of board-level sustainability committees with special oversight role for sustainability processes and reporting may help in assessing executive’s sustainable behaviour and to consider this assessment through the inclusion of sustainability-related targets in CEO compensation contracts. This paper focuses on the role of governed sustainability information, i.e. the existence of sustainability committees and independent external assurance, on the inclusion of sustainability-related targets in CEO compensation contracts of UK FTSE350 companies.

We find sustainability committees are associated with the inclusion of sustainability-related targets in compensation contracts. Moreover, firms that have their sustainability reports externally assured disclose sustainability-related incentives in their compensation reports. There is no joint impact between the use of independent external assurance and the role of sustainability committees on CEO compensation contracts. Compared to other providers, assurance provided by Big4 accounting firms is more likely to be associated with the inclusion of sustainability-related targets. Also, highly sustainable companies are more likely to monitor sustainable behaviour, i.e. have a stronger association between sustainability-related terms in compensation contracts and both voluntary assurance and sustainability committees. Finally, our results highlight the potential of assured sustainability reports in assessing CEO performance over sustainability-related tasks, especially when sustainability metrics are included in CEO compensation contracts.

Overall, our findings suggest that sustainability assurance is rewarded with higher CEO compensation and that companies concerned about achievement of sustainable goals adopt relatively more objective and credible monitoring mechanisms. It is not only sustainability committees but also voluntary independent external assurance that affects the inclusion of sustainability targets in compensation contracts. Our findings also suggest that if compensation committees take into account CEO involvement in sustainable strategies and link it to their compensation, then it is likely to improve sustainable performance and reduce pressures to maximise short-term performance. Also, voluntary assurance is likely to reflect a commitment to deeper values such as trust, credibility and confidence in reporting.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: the next section reviews the literature. The third section discusses the institutional background of sustainability committees and assurance in UK. The fourth section outlines the theoretical framework and develops the hypotheses. The fifth section sets out the research study in terms of sample, data and model. ‘Results and Analysis’ section reports our empirical findings, and the final section draws conclusions.

Literature Review

Executive Compensation and Social Performance

Most of the literature on CEO compensation and social performance has been done in the US context (e.g. Cai et al. 2011; Callan and Thomas 2011, 2014), Canada (e.g. Mahoney and Thorn 2005, 2006), the Netherlands (e.g. Kolk and Perego 2014) or in international settings (e.g. Francoeur et al. 2017; Maas and Rosendaal 2016). The results of exiting studies are mixed. Coombs and Gilley (2005) find employee performance has a positive impact on bonuses. O’Connell and O’Sullivan (2014) use agency theory to examine the role of non-financial measures in strategic performance management framework in terms of motivation, ability and effect on long-term value. They find customer satisfaction enhances future profitability and that firms are likely to link CEO compensation to such a lead indicator. Callan and Thomas (2014) use a multiequation model to examine the link between executive compensation and CSR and find pay-for-performance relationship is significant and is linked with social performance, while Callan and Thomas (2011) find CSR is a determinant of CEO pay. Both studies use an index measure of the firm’s corporate social performance. Although O’Connell and O’Sullivan (2014) and Callan and Thomas (2014) investigate whether social performance is connected to CEO compensation, they do not explore the monitoring role of corporate governance mechanisms on executive compensation. Hong et al. (2015) identify corporate governance as a determinant of managerial incentives for social performance and examine the role of executive compensation contracts that explicitly incentivise managers for CSR. They argue that if CSR activities maximise shareholders’ value, then it is more likely that executive compensation contracts will be linked to CSR measured using KLD scores for social performance.

Prior literature also reports a negative association between executive compensation and social performance. Stanwick and Stanwick (1998, 2001) find a negative relationship between CSR performance and compensation measured using annual salaries and bonuses, while Cai et al. (2011) examine the impact of corporate social performance on executive compensation using a sample of large US firms covering the period 1996–2010 and find CSR adversely affects both total compensation and cash compensation. Collett Miles and Miles (2013) and Frye et al. (2006) compare CEO compensation among socially responsible firms and non-socially responsible firms and find the link between CEO pay and firm performance is weaker for socially responsible firms.

There are studies that find no evidence or partial evidence on the link between CEO compensation and corporate social performance. Studies such as McGuire et al. (2003) find no significant relationship between incentives and firm social performance, and Benson and Davidson (2010) find that improved stakeholder management does not result in additional CEO compensation. Cordeiro and Sarkis (2008) test whether there is an explicit linkage between executive compensation and environmental performance and find partial evidence of a linkage and suggest that it is likely that US companies utilise the linkage between top executive compensation and environmental performance as a management communication strategy to maintain their standing with stakeholders. Berrone and Gomez-Mejia (2009a) examine the association between pollution reduction programs and CEO compensation and find that only environmental practices that have the potential to improve future firm performance are rewarded. What is particularly evident about prior research papers is that the majority of them measure CSR using an index measure for corporate social performance such as KLD scores or they include only a measure of the environmental dimension of CSR. Berrone and Gomez-Mejia (2009b) argue that the mixed findings in terms of the association between CEO compensation and social performance could be related to social performance measurement.

Executive Compensation and Sustainability Reporting

Maas (2015) argues that companies can use incentives by integrating corporate social performance targets into executive compensation. Maas and Rosendaal (2016) examine the inclusion of sustainability targets in executive compensation using 490 listed companies from 11 countries and find companies use sustainability targets that focus on social issues in their remuneration plans.Footnote 2 Kolk and Perego (2014) use four case studies from the Netherlands to investigate the performance criteria in bonus programmes and assess whether the introduction of sustainability-related bonuses is a credible signal or just a mechanism to keep up bonus levels. Francoeur et al. (2017) examine firms’ commitment to environmental sustainability based on key data, such as actual performance, reporting procedures, policies and guidelines, and management systems, obtained from public reports and financial accounts, interviews with stakeholders and media files. They find environment-friendly firms pay their CEOs less total compensation and rely less on incentive-based compensation than their counterparts.Footnote 3 The relationship is stronger in institutional contexts where national environmental regulations are weaker.Footnote 4 Although they argue that compensation committees should consider psychological and institutional factors when designing compensation for CEOs, their study does not take into consideration corporate governance mechanisms which may affect the relationship between social performance and executive compensation.

Schiehll and Bellavance (2009) examine non-financial performance measures used as a component of pay-for-performance plans to align and compensate executive actions and to reflect the benefits of CEOs strategic planning and business initiatives. They argue that incorporating non-financial performance measures in executive contracts enhances investors’ decisions and boards’ ability to increase shareholder wealth by monitoring managerial actions. Davila and Venkatachalam (2004) investigate whether CEOs are compensated based on non-financial performance measures and argue that non-financial metrics that are explicitly disclosed in compensation contracts are useful when they provide incremental information about the agent’s efforts beyond financial metrics.

There is limited research on the relationship between executive compensation and sustainability assurance. A recent study by Brown-Liburd and Zamora (2014) argues that managerial pay that is explicitly tied to sustainability information is value relevant and that pay-for-performance incentivises managers to substantially invest in sustainability strategies and to report strong sustainability performance. They argue managers need to seek independent assurance of sustainability information to signal credibility, and investors will highly assess independently assured information that is linked to incentive system.Footnote 5 The study finds in the presence of pay-for-CSR performance and high CSR investment level, investors’ stock price assessments are greater only when CSR assurance is also present. Moser and Martin (2012) argue that the voluntary and unverified sustainability disclosures raise reliability and credibility concerns which require external assurance, while Berrone and Gomez-Mejia (2009b) call for monitoring mechanisms to assess the credibility of sustainability information.

Our paper aims to contribute to the sustainability assurance and governance literature by examining the role of governed sustainability information on top management pay. It aims to investigate the impact of sustainability reporting assurance and the existence of sustainability committees on CEO compensation after controlling for governance mechanisms and firm-specific factors.

Sustainability Committees and Assurance in the UK

The UK Companies Act (2006) developed the concept of ‘enlightened shareholder value’ stating that directors will be more likely to achieve long-term sustainable success if their companies consider issues related to the environment, community involvement and other long-term values. UK companies are increasingly recognising that their day-to-day operations have environmental, social and economic impact. They are also increasingly disclosing voluntarily on sustainability issues through a variety of channels including the publication of stand-alone sustainability reports. Many have voluntarily established formal structures, such as board-level sustainability committees to promote sustainability issues with explicit responsibilities for oversight over social and environmental impact of corporate activities, reviewing and making recommendation regarding stakeholders’ proposals in relation to sustainability matters, reviewing and assessing company policies and practices with respect to sustainability issues including product safety, charitable contribution and environmental health (Financial Reporting Council 2016). The establishment of a board-level sustainability committee can indicate that the company has an active strategic position with regard to stakeholders (Ullmann 1985). It may be seen as an effective monitoring device for ensuring the quality of stakeholders’ engagement process and improving the range of disclosures provided to stakeholders (Michelon and Parbonetti 2012).

In the UK directors of listed companies are obliged to disclose narrative information on material issues, including those related to social and environmental risks, which are likely to impact on firm performance (KPMG 2010). The reporting of sustainability policies and practices without independent assurance however is of reduced value to stakeholders. In the UK, as in other countries, independent assurance of sustainability reports is not mandatory (Junior et al. 2014) and thus companies may voluntarily adopt assurance to improve internal reporting process and quality of reported information, and to garner stakeholder confidence in reported information (KPMG 2008). The voluntary adoption may also reflect and signal a commitment to deeper values such as trust, credibility and confidence.

There are three major assurance providers in the UK: accountants (typically Big4 firms), certification bodies and specialist consultancies. Prior literature suggests assurance provided by Big4 accounting firms is perceived to be of higher quality due to their extensive experience in financial statement auditing and expertise related to risk assessment, planning and consideration of materiality in providing assurance as well as reputational capital (Gray 2000; Hodge et al. 2009; Moroney et al. 2012). Romero et al. (2010) argue that assurance statements issued by accountants are perceived to be of higher quality than those issued by non-accountants. Assurers who are accountants are deemed to provide cautionary assurance on environmental disclosures, while consultant assurers are perceived as providing a reasonable level of assurance for their clients because accountants are subject to professional regulation and tend to be concerned about litigation arising from legal responsibilities relating to social and environmental reporting (Dixon et al. 2004; O’Dwyer and Owen 2005; Moroney et al. 2012). Assurers who are accountants are also perceived as providing an objective and independent opinion which is considered more important than the cost associated with assurance services (Knechel et al. 2006).

In the UK institutional setting, SRA lacks credibility due to the absence of one unified benchmark against which sustainability reporting can be evaluated and the absence of a single generally accepted ‘common currency’ for making a professional assessment of the accuracy and completeness of sustainability reporting (Smith et al. 2011; p. 426). The current guidelines originate from very different professional and ethical rules and institutional bodies including professional bodies, corporations and non-governmental organisations (NGOs).Footnote 6 These groups provide guidance for SRA practitioners and corporations vis-à-vis reporting and assurance standards that are different in scope and content (see Smith et al. 2011 for more details).Footnote 7 Moreover, assurance providers use aspects of the various standards on an ad hoc ‘pick and mix’ basis (CorporateRegister.com 2008, p. 13). The complexity of SRA practice in the UK stresses the need for further investigation.

Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Development

Sustainability and sustainable development are concepts evolving in a world where social issues are becoming increasingly important. Sustainable strategies adopted by companies are important not only for societies and the environment but also for corporate survival (Deegan and Gordon 1996). Companies are expected to be accountable not only for their operations but also for the impact of their operations and to legitimise their activities. Berrone and Gomez-Mejia (2009a) argue that firms should reward their executives for any sustainable behaviour because it brings legitimacy, improves performance, enhances reputation with stakeholders and enhances firms’ chances of survival. Callan and Thomas (2014) argue that pay-for-performance should be expanded to include social performance so that compensation plans incentivise the achievement of social and environmental goals. If the company is adopting a sustainable strategy where social and environmental aspects are an important focus, then it would be reasonable to expect compensation contracts to incorporate social and environmental performance indicators in addition to financial ones (Deegan and Islam 2012).

Previous literature suggests that companies should provide CEOs with explicit incentives in their compensation package if they want to increase their environmental commitment (Stanwick and Stanwick 2001, 2003; Cordeiro and Sarkis 2008; Berrone and Gomez-Mejia 2009a). According to stakeholder theory, compensation committees will respond to pressures from stakeholders including environmental activist and social investment funds by explicitly using social targets in CEO compensation (Maas 2015). Although compensation schemes mainly focus on financial metrics and tend to disregard the value to other stakeholders, inclusion of non-financial metrics may lead to good sustainable performance and enhance corporate survival (Baron 2008). CEOs can be held accountable for the sustainable performance of the firm if firms include sustainability-related terms in executive compensation plan (Maas and Rosendaal 2016).

Some managers might be willing to adopt practices that are expected to have social value, while others may avoid them due to uncertainties about financial outcomes (Berrone and Gomez-Mejia 2009a). Therefore, to motivate CEOs to engage in actions that lead to good sustainable performance compensation committees need to provide linkage to sustainability in CEOs’ compensation contracts (Berrone and Gomez-Mejia 2009a). Hong et al. (2015) identify corporate governance mechanisms as determinants of managerial incentive for social performance but failed to include related board subcommittees in their study. Berrone and Gomez-Mejia (2009a) argue that when sustainability duties are explicitly and formally delegated to a subgroup of a board, the board is in a better position to assess executive performance on these duties and to consider this assessment in CEO pay decisions. Non-financial performance targets are likely to be determined by the compensation committee in consultation with the board-level sustainability committee. From an agency theory perspective, the extent to which firms’ sustainability committees exercise oversight and monitoring of sustainability strategy and reporting will influence any reduction in information asymmetries, allowing for more accurate assessment of sustainable performance and a tighter linkage between performance and total pay (Berrone and Gomez-Mejia 2009a, p. 108).

The existence of sustainability targets in CEO compensation may pose a credibility question about positive sustainable performance and raises the need for controllability in sustainable-related targets (Maas and Rosendaal 2016; Berrone and Gomez-Mejia 2009b). The complexity of sustainable strategies and actions goes beyond the expertise of board members and sustainability committees and in the presence of explicit pay for sustainability performance in CEO compensation voluntary assurance can add credibility and help to ensure that appropriate measurement standards have been applied (Brown-Liburd and Zamora 2014). Berrone and Gomez-Mejia (2009b) emphasise that the use of compensation tied to sustainability needs to be monitored through external monitoring mechanisms.

Assurance can signal that sustainability information is reliable and it can also help companies to assess the achievement of their social performance goals (Simnett et al. 2009; Cohen and Simnett 2014), increase the transparency and credibility of information (Peters and Romi 2015) and increase corporate legitimacy and accountability (Kolk and Perego 2014). Additionally, sustainable firms are more likely to link senior executive compensation to environmental and social metrics, have greater interest in linking executive compensation to non-financial information and more likely to be committed to a third-party assurance to verify the accuracy of such information (Brown-Liburd and Zamora 2014; Eccles et al. 2014). Therefore, we expect sustainability assurance to be linked to compensation systems and inclusion of sustainability-related targets in compensation plans.

Board-level sustainability committees are put in place to monitor, guide and reward sustainable actions (Berrone and Gomez-Mejia 2009a), and thus, they can affect the relationship between sustainability performance and CEO compensation. In addition to the establishment of a committee specialised in social and environmental issues, Berrone and Gomez-Mejia (2009a) suggest the use of alternative monitoring mechanisms such as external environmental audit to better manage firms’ sustainable behaviour. This suggests the need for further investigation of the joint impact of voluntary assurance and sustainability committees and whether the role of these two mechanisms is complementary or substitutive.

The inclusion of sustainability-related targets in CEO compensation plans is likely to be affected by the governance of sustainability information, especially voluntary assurance of sustainability reporting and board-level sustainability committees. Thus, in this paper, we test the following hypotheses:

H1

Companies with sustainability reports that are externally assured are more likely to include sustainability-related terms in CEO compensation contracts.

H2

Board-level sustainability committees are associated with the inclusion of sustainability-related terms in CEO compensation contracts.

H3

Board-level sustainability committees substitute/complement the existence of independent external assurance in the provision of sustainability-related terms in CEO compensation contracts.

Research Design and Data

Sample

Our study is based on an initial sample of companies continuously listed in the UK FTSE350 during the 2011–2015 period. From our initial sample of 1590 (318 × 5 years), we lose some observations due to missing data on some of the variables collected from DataStream. Our final sample consists of 1345 observations.Footnote 8 We use Thomson Reuters Asset4 which provides data on the adoption and non-adoption of sustainability policies.Footnote 9 We supplement this with information extracted from companies’ annual reports to further investigate the extent of sustainability-related terms used in CEO compensation and the Global Reporting Initiative database for the disclosure of the existence of independent external assurance. CEO financial compensation data and corporate governance data are obtained from BoardEx, and other financial data are obtained from DataStream.

Regression Model, Data and Variables

We use logistic regression to examine the role of governed sustainability information represented by sustainability reporting assurance (SRA) and the existence of sustainability committee on CEO compensation tied to sustainability. We apply one-year lag to our independent variable and other control variables. We therefore estimate how SRA, SUSCOM and other governance and firm-specific variables predict the subsequent increase in the use of sustainability information in CEO compensation contracts. We use the following model to test the first two hypotheses H1 and H2:

We test our third hypothesis and investigate whether SRA complements or substitutes SUSCOM in affecting CEO compensation by interacting these two governance mechanisms using the following model:

The variables are defined in Table 1.

The dependent variable in the regression model is SUSCONTRACTINGt. We review companies’ annual reports and extract sentences/paragraphs that include references to sustainability in CEO compensation contracts.Footnote 10 If compensation is linked to sustainability activities, SUSCONTRACTINGt takes the value of 1 (the firm is coded as offering sustainability incentives) and zero otherwise (Hong et al. 2015). For additional test, we also consider the three financial components of CEO compensation: (i) salaries and bonuses which capture short-term compensation, (ii) equity-based compensation includes the value of restricted stock, stock options and other elements of long-term incentive plans (LTIPs) as reported in the BoardEx database to capture long-term compensation and (iii) total compensation measured as the sum of CEO salary, bonus, the value of equity-based compensation and other compensation. Consistent with previous studies (McGuire et al. 2003; Cordeiro and Sarkis 2008; Cai et al. 2011; Francoeur et al. 2017), we use CEO compensation as a proxy for top executive compensation because CEOs and other top executives are accountable for engaging in sustainable strategies including sustainability reporting assurance.Footnote 11

Our variables of interests are sustainability reporting assurance (SRAt−1), measured using a dummy variable equal to 1 if sustainability reports are externally assured and zero otherwise, and the existence of board-level sustainability committee measured using a dummy variable equal to 1 if a committee exists and zero otherwise.Footnote 12 We expect a positive and significant association between both the independent external assurance of sustainability reports and the existence of sustainability committees on CEO compensation. For additional analysis, we further measure sustainability reporting assurance using an alternative measure, SRAProvidert−1, using a scale where SRAProvidert−1 equals to 3 if assurance is provided by Big4 accounting firm; 2 if assurance is provided by non-Big4 accounting firm; 1 if assurance is provided by non-accounting firm; 0 if no assurance service is provided. This enables us to provide preliminary evidence on whether assurance quality affects the relationship and we expect a significant positive association between SRAProvidert−1 and CEO compensation to indicate that external assurance provided by Big4 accounting firm is more important than external assurance provided by other assurance providers.

Prior literature shows a link between governance variables and CEO compensation (Gomez-Mejia and Wiseman 1997; Murphy 1999; Denis 2001; Daily et al. 2003; Hermalin 2005; Cordeiro and Sarkis 2008; Cai et al. 2011), and Cai et al. (2011) note that firms tend to respond to increase in monitoring provided by corporate governance by increasing CEO compensation. We thus include a number of governance variables, i.e. board size, board independence, board meetings and board expertise, in our regression models. Larger boards with higher proportion of independent directors who meet regularly and have financial expertise are deemed more effective monitors and more likely to influence executive compensation (Murphy 1999; Denis 2001; Hermalin 2005; Cordeiro and Sarkis 2008). We also include CEO ownership as a control variable because prior studies suggest it is a potential driver of CEO compensation (Finkelstein 1992; Berrone and Gomez-Mejia 2009a; Cai et al. 2011). We measure it as the percentage of company’s shares owned by the CEO.

Following the executive compensation literature we control for a number of firm-specific variables which may affect CEO compensation. We include firm size (SIZEt−1) measured by the natural log of total sales (Mahoney and Thorn 2005; Deckop et al. 2006; Callan and Thomas 2014; O’Connell and O’Sullivan 2014; Hong et al. 2015) and profitability measured by return on equity (ROEt−1). Prior studies suggest that size and profitability are important drivers of executive compensation and find a positive relationship with CEO compensation (Callan and Thomas 2014; Hong et al. 2015). O’Connell and O’Sullivan (2014) argue that including size in the regression model controls for the relation between compensation and firm magnitude. Larger firms are more likely to hire superior executives who get a higher pay (Cai et al. 2011). We also include financial leverage (LEVt−1) measured by total debt to total asset ratio. The level of debt may motivate firms to use CEO compensation to reduce agency problem (Francoeur et al. 2017). TOBINSQt−1, calculated by dividing the sum of firm equity value, book value of long-term debt and current liabilities by total asset, is also included to reflect a firm’s growth opportunities (Chung and Pruitt 1994; Berrone and Gomez-Mejia 2009a). Firms with higher growth opportunities need more qualified executives who are likely to be offered better compensation (Cai et al. 2011). We include risk measured using the firm market beta.

We also control for industry (IND) by grouping firms in the sample using the one-digit Standard Industry Classification (SIC) codes (Francoeur et al. 2017). For additional analysis we classify firms as sustainability-sensitive and non-sustainability-sensitive. Following prior studies (see for e.g. Patten 1991; Deegan and Gordon 1996; Patten 2002), we identify firms in the oil and gas, chemical, mining, utilities, forest and paper products, beverage, tobacco, and aerospace and defence industries as sustainability-sensitive because companies in these industries are assumed to have greater incentives for providing a positive social image and their activities have greater impact on the environment.Footnote 13

Results and Analysis

Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 summarises our sample and reports descriptive statistics for the variables used in the models. The mean value of SUSCONTRACTINGt−1 is 0.493 and indicates approximately half of the companies in our sample disclose the inclusion of sustainability-related targets in their CEO compensation contracts. On average, CEOs receive a total compensation of £11,600,000. (Median value is £8,700,000.) The mean value of CEO salary is £1,260,774, and the mean value of CEO bonus is £1,152,365. The mean value of long-term compensation (LTCOMt) is £3,378,200. (Median value is £2,000,000.) LTCOMt on average accounts for 30% of the total compensation, and it is higher than the average of salaries and bonus together. This is consistent with Francoeur et al.’s (2017) observation that UK and US firms use long-term compensation the most and have the highest paid CEOs.

With regard to sustainability assurance and corporate governance variables, the mean value of SRAt−1 in our sample is 0.373 and the mean SRAProvidert−1 is 1.302 and indicates a large proportion of our sample firms have independent external assurance from non-accounting consultancy firms. The mean SUSCOMt−1 is 0.784, mean board size (BODSIZEt−1) is 9.416, and mean board independence (BODINDt−1) is 0.665 which means that more than half of the board members in our sample are independent directors. The boards of directors meet on average 8.878 times a year, and over half of the board members have financial expertise. The mean CEOOWNt−1 is 0.645. This is lower than the 1.69 mean reported by Cai et al. (2011) and the 1.80 mean reported by Berrone and Gomez-Mejia (2009a). With respect to firm-specific variables, we find mean firm size (SIZEt−1) measured by total sales is £7,464,584, mean ROEt−1 is 0.221, mean leverage (LEVt−1) is 0.205, mean Tobin’sQt−1 is 0.412, and mean BETAt−1 is 0.928 which is consistent with the value reported by Francoeur et al. (2017).

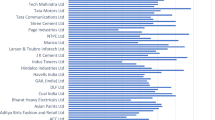

Industry means for the regression variables show that disclosure of sustainability-related targets in CEO compensation contracts is highest for the oil and gas, telecommunication and consumer goods sectors. On average, the consumer goods sector has the highest long-term incentives and total CEO compensation. Also the consumer goods industry has the highest mean (0.430) for sustainability reporting assurance and a relatively high mean (0.821) for SUSCOMt−1, and the utility sector has the highest mean (0.879) for SUSCOMt−1.

In Table 2 we also report the means and t tests of compensation components for companies that have sustainability reporting assurance and those that do not (SRAt−1=0/1) and for firms with sustainability committees and those without (SUSCOMt−1=1/0). We find firms that have sustainability assurance have higher mean SUSCONTRACTINGt, i.e. sustainability-related incentive component included in the compensation contract. (Mean value is − 5.809 and is significant at p < 0.01.) This is also the case for firms with a board-level sustainability committee. (Mean value is − 8.401 and is significant at p < 0.01.) We also find that firms that have their sustainability reports externally assured pay higher total compensation (mean value is − 2.492 and is significant at p < 0.05) and higher salaries (mean value is − 1.761 and is significant at p < 0.10). Finally, firms that have a sustainability committee pay higher total compensation (mean value is − 1.908 and is significant at p < 0.10) and higher salaries (mean value is − 2.003 and is significant at p < 0.05).

Table 3 shows the correlation matrix for variables used in our analysis. We find that sustainability reporting assurance (SRAt−1) has a significant and positive correlation with SUSCONTRACTINGt. It also has a significant and positive correlation with CEO total compensation and CEO salaries. SUSCOMt−1 has a significant and positive correlation with SUSCONTRACTINGt, CEO salaries and total compensation. Other governance variables including BODSIZEt−1, BODINDt−1 and CEOOWNt−1 also have a significant and positive correlation with SUSCONTRACTINGt. Among firm-specific variables, SIZEt−1, LEVt−1 and BETAt−1 are positively correlated with SUSCONTRACTINGt. The correlation between independent variables indicates that multicollinearity is unlikely to be a concern. The variance inflation factor (VIF) for each independent variable being regressed is reported in Table 3, and it shows that the lowest value is 1.04 and the highest value is 2.24. (The average variance inflation factor value is 1.46.) This also suggests the absence of multicollinearity.

Empirical Tests and Findings

Table 4 presents the results on the relationship between assurance and inclusion of sustainability-related terms in compensation terms. Since SUSCONTRACTINGt is a dummy variable, taking the value of 1 if firm’s compensation report has sustainability-related targets and 0 otherwise, we use logistic regression. Model 4.1 tests the impact of SRAt−1, SUSCOMt−1 and other board variables and firm-specific variables on SUSCONTRACTINGt. Results show that both SRAt−1 and SUSCOMt−1 are significant (p < 0.01) and positively associated with SUSCONTRACTINGt, thus supporting our hypotheses (H1 and H2) that companies with board-level sustainability committees and with independent external assurance of their sustainability reports are more likely to include sustainability-related terms in CEO compensation contracts. Our results support the argument that the existence of sustainability committees helps to assess executive performance on duties related to sustainability issues (Berrone and Gomez-Mejia 2009a). They are also consistent with the view that independent external assurance of sustainability reports is more likely to provide controllability of sustainability-related targets and enhance the credibility of sustainable performance (Maas and Rosendaal 2016; Berrone and Gomez-Mejia 2009b).

Model 4.2 tests the joint impact of SRAt−1 and SUSCOMt−1 and our third hypothesis on whether the role of sustainability committee and independent external assurance on the inclusion of sustainability-related terms in CEO compensation contracts is complementary or substitutive. We find the interaction between SRAt−1 and SUSCOMt−1 is negative but not significant, while SUSCOMt−1 remains positive and significant (p < 0.05) and SRAt is positive and significant (p < 0.10). Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that there is no joint impact between SRAt−1 and SUSCOMt−1 on the CEO compensation contract. Our results (see Model 4.2) do not lend support to our hypothesis in relation to the substitutive versus complementary effects.

Additional Analysis—Assurer Quality

To examine whether there are variations of sustainability reporting assurance in terms of assurance provider and the impact this may have on CEO compensation we undertake additional analysis in Models 4.3 and 4.4 using SRAProvidert−1 as an alternative measure of SRAt−1. Our results show that SRAProvidert−1 is positive and significant (p < 0.01), suggesting that external assurance provided by Big4 accounting firm is more likely to be linked to the existence of sustainability-related targets in CEO compensation. This is consistent with prior literature and the argument that assurance provided by Big4 accountancy firm is of higher importance than external assurance provided by other assurance providers (see for e.g. Junior et al. 2014; Cheng et al. 2012; Hodge et al. 2009). We find SUSCOMt−1 is positive and significant (p < 0.01). Model 4.4 tests the impact of the interaction variable between SRAProvidert−1 and SUSCOMt−1 along with their individual impact on SUSCONTRACTINGt. We find the interaction variable is not significant and negatively associated with SUSCONTRACTINGt, while both SUSCOMt−1 and SRAProvidert−1 remain significant and positively associated with SUSCONTRACTINGt. Therefore, our results in Models 4.3 and 4.4 are consistent with previous models.

Among other governance variables we find that BODINDt−1 is positive and significant (p < 0.05) in all models (4.1–4.4), and BODEXPt−1 and CEOWONt−1 are positive and significant (p < 0.01) in all models (4.1–4.4). Among firm-specific variables, we find SIZEt−1 is positive and significant (p < 0.01), and LEVt−1, and BETAt−1 are positive and significant (p < 0.05) in all models. These findings are generally consistent with expected direction on relationships.

Additional Analysis—Sustainability-Sensitive Firms

Table 5 provides additional analysis for sustainability-sensitive firms and non-sensitive firms. We classify firms as sustainability-sensitive when they operate in the oil and gas, chemical, mining, utilities, forest and paper products, beverage, tobacco and aerospace and defence industries (see for e.g. Patten 1991; Deegan and Gordon 1996; Patten 2002). We have 405 firms classified as sustainability-sensitive in our sample and 940 classified as non-sustainability-sensitive. We use the same modelling as in Table 4, Models 5.1 and 5.2 relate to the sustainability-sensitive firms and Models 5.3 and 5.4 relate to the non-sustainability-sensitive firms. Results show that for sustainability-sensitive firms both SRAt−1 and SUSCOMt−1 are positive and significant (p < 0.05) with SUSCONTRACTINGt (Model 5.1). The interaction between the two variables is not significant, but the individual effects of SRAt−1 and SUSCOMt−1 remain positive for both variables and significant for the latter (Model 5.2).Footnote 14

For non-sustainability-sensitive subsample, we find that SUSCOMt−1 remains positive and significant with SUSCONTRACTINGt, while SRAt−1 is positive but not significant (Models 5.3 and 5.4). Results for sustainability-sensitive subsample are consistent with our previous findings and suggest sustainability-sensitive companies are characterised by a distinct governance structure which reflects interests of stakeholders and they are likely to link top management compensation to metrics that include sustainability performance.

Additional Analysis—Assurance and CEO Compensation

Table 6 presents the results relating to the impact of sustainability reporting assurance on CEO financial compensation. Model 6.1 uses SALARYt as the dependent, Model 6.2 uses BONUSt, Model 6.3 uses LTCOMt, and Model 6.4 uses total compensation (CEOCOMt).Footnote 15 We find SRAt−1 is positive and marginally significant with LTCOMt (Model 6.3) and CEOCOMt (Model 6.4), while SUSCOMt−1 is not significant in all models. It could be that firms with board-level sustainability committees do not rely on evidence from the assurance service industry in assessing CEOs’ financial rewards.

When we investigate these relationships further by dividing our sample into sustainability-sensitive and non-sustainability-sensitive firms (untabulated), we find that only in the sustainability-sensitive subsample SRAt−1 appears to be significant (p < 0.10) for LTCOMt and CEOCOMt but not in the non-sustainability-sensitive subsample. We note that SUSCOMt−1 is not significant in both subsamples.

Additional Analysis—Endogeneity Test

We recognise that our sample may be subject to endogeneity issues. Although we used lagged SRA to address the potential problem of simultaneity and also introduced a comprehensive set of control variables that have been used in CEO compensation literature to avoid omitted variables issue, there might still be some unobserved factors that might drive our results. Thus, we also use instrumental variable approach based on two-stage least square (2SLS) estimation to mitigate potential simultaneous causality. It requires finding a variable that is correlated with the first-stage dependent variable (SRA) but not correlated with the second-stage dependent variable (CEO compensation) (Moffitt 1999). To accommodate this issue, following Cai et al. (2011) we use industry-mean SRA as an instrumental variable and we expect that firm-level SRA to be correlated with its industry norms, while it is unlikely that industry-mean SRA is linked to CEO compensation.Footnote 16 We use Durbin–Wu-Hausman test to investigate the presence of endogeneity assuming SRAt−1 is an endogenous variable. Accepting the null hypothesis that our variable is exogenous confirms the absence of endogeneity effects. Durbin–Wu-Hausman results confirm that the hypothesis could not be rejected as the p value is not significant for each measure of CEO compensation and suggests SRAt−1 is exogenous for each measure of CEO compensation.Footnote 17 Based on the Durbin–Wu test we assume endogeneity is not present.

Recognising that there is no specific test that can measure the impact and size of endogeneity accurately (Van Lent 2007), we apply another approach to check for endogeneity. Heckman (1976, 1979) proposed a two-stage estimation procedure using the inverse Mills’ ratio to take endogeneity bias into account.Footnote 18 In the first stage, we run a probit model using SRA as the dependent variable. The estimated parameters are used to calculate the inverse Mills’ ratio, which is then included as an additional explanatory variable in the second-stage estimation (Greene 1993).Footnote 19 The choice of assurance could be related to potential firm-specific characteristics such as size, profitability, growth, risk and industry. Large companies that are profitable, risky and from sustainability-sensitive industries (such as oil and gas, basic materials and utilities sectors) are more likely to demand external assurance and pay higher compensation ceteris paribus. Thus, failure to control for this correlation is likely to yield a biased estimate of SRA influence on CEO compensation. Results from the first-stage regression are reported in “Appendix” and show that among firms-specific variables, SIZEt, LEVt and BETAt have positive and significant associations (p < 0.01) with SRAt, and ROEt has a positive and significant association with (p < 0.10) with SRAt.

Table 7 reports the coefficient estimates from the second-stage regression. The results show that both SRAt−1 and SUSCOMt−1 have positive and significant associations (p < 0.01) with SUSCONTRACTINGt (Model 7.1) and not significant for CEO financial compensation components (Models 7.2–7.5). The lambda term (INVERSEMILL) is insignificant in all models, suggesting that sample selection bias is not present and that OLS regression is appropriate.Footnote 20

Additional Analysis—the Impact of Sustainability Compensation Terms on SRA

We further investigate whether reverse causality is present. We investigate whether the inclusion of sustainability metrics in CEO contracts is likely to help CEO to focus attention and insure sustainability initiatives are implemented. This may lead to a need for assured sustainability reports. The inclusion of sustainability compensation terms may result in the adoption of independent external assurance. We examine the effect of sustainability compensation terms and corporate governance mechanisms on the likelihood that a firm chooses SRA using a logistic regression model.Footnote 21 Subsequent tests incorporate a logistic regression model to examine whether the inclusion of sustainability compensation terms and corporate governance mechanisms impact the choice of assurance providers.

Prior literature argues that SRA is a function of industry and firm-related factors (see Simnett et al. 2009; Ruhnke and Gabriel 2013). Moreover, there has been an increasing recognition of the role of corporate governance mechanisms including board of directors and sustainability committees in monitoring sustainability performance and reporting (Post et al. 2011; Zhang et al. 2013; Peters and Romi 2014; Trotman and Trotman 2015).Footnote 22 The voluntary demand for independent external assurance could help reassuring the accomplishment of the sustainability-related tasks.

Table 8 presents the results on the impact of the inclusion of sustainability-related terms in compensation contract on sustainability reporting assurance. In Model 8.1, we examine the impact of SUSCONTRACTINGt and firm-specific factors on SRAt, and in Model 8.2 we incorporate corporate governance variables in the regression test. Models 8.3 and 8.4 repeat the test using SRAProvidert as the dependent. Results show that SUSCONTRACTINGt is significant (p < 0.01) and positively associated with SRAt. Among corporate governance variables, we find that SUSCOMt is significant (p < 0.01) and positively associated with SRAt, and BODSIZEt is significant (p < 0.10) and positively associated with SRAt. BODEXPt is significant (p < 0.05) and negatively associated with SRAt. We also find, among firm-specific characteristics, that SIZEt, TOBINSQt and BETAt are significant and positively associated with SRAt. Models 8.3 and Model 8.4 provide qualitatively similar findings when using SRAProvidert as the dependent.Footnote 23

Summary and Conclusion

This paper provides evidence on the impact of sustainability reporting assurance on CEO compensation after controlling for corporate governance mechanisms and firm-specific factors. We respond to calls for more research in the area of sustainability assurance (Cohen and Simnett 2014) and seek to extend the literature which has largely ignored governance mechanisms related to social and environmental issues (Berrone and Gomez-Mejia 2009a). Specifically, we investigate whether companies reward CEOs for sustainability reporting practices. Our findings suggest that companies with board-level sustainability committees are more likely to include sustainability-related targets in CEO compensation contracts. Moreover, our results also suggest that companies with voluntary sustainability assurance are more likely to include sustainability terms in CEO compensation contracts and have higher CEO compensation and that there is no joint impact between the voluntary assurance of sustainability reports and the role of sustainability committees on CEO compensation contract. We also find sustainability-related targets in CEO compensation contracts are more likely to be included when the company has voluntary assurance, provided by a Big4 firm, and is operating in sustainability-sensitive industry. Further test investigates the reverse causality issue, in particular whether inclusion of sustainability-related targets in CEO compensation leads to a need for assured sustainability report such that the sustainability or compensation committee could evaluate whether the CEO has performed well the sustainability-related tasks. Results show that sustainability metrics included in compensation plans lead to a demand for independent external assurance.

Our paper has a few limitations which provide opportunities for future research. The main focus of our paper is to examine the direct impact of sustainability reporting assurance on CEO compensation. We estimate how SRA predicts the subsequent increase in CEO compensation and address the potential problem of causality and simultaneity. Future research can complement our study by considering the indirect link between SRA and CEO compensation through corporate financial performance. It could also explore patterns in SRA/SUSCOM adoption using a wider, longitudinal data set. Moreover, our sample is based on the UK FTSE350 that tend to be large in size. Further research may examine the impact of SRA on CEO compensation in smaller firms and in other institutional contexts in which governance of sustainability reporting is different.

Our paper is likely to be of interest to companies, regulators and practitioners. In order to ensure that sustainability is sufficiently embedded with an organisation, companies need to consider sustainability-related targets in compensation contracts which will motivate boards and management to achieve those targets. Irresponsible actions that have a negative impact on sustainability and company’s reputation can still implicitly affect incentive awards. However, a broader push to more explicitly tie sustainability metrics to core business models can be a more effective strategy and a useful reminder that sustainability is a major corporate concern (Burchman and Sullivan 2017). Moreover, sustainability metrics incorporated in performance measurement and compensation scheme need to be well-defined metrics critical in achieving sustainability-related objectives; otherwise, sustainability may become an elusive goal. Independent external assurance should help in assessing the quality of these metrics.

While there is a growing trend in companies linking sustainability to executive compensation, such linkage continues to be an evolving practice that requires companies to be held to a higher standard of accountability for their practice (Glass Lewis 2016). Investors seem to be showing a growing interest in companies linking compensation and sustainability and are driving part of the growth of such evolving practice. The 2013 report by EY and GreenBiz Group (2013) summarises the results based on a survey consisting of executives and corporate leaders to provide their expertise and perspective on corporate initiatives, laws and regulations—30% of corporate respondents stated that they had received inquiries from shareholders regarding their practice in linking executive compensation to sustainability metrics, while 21% stated that compensation was partially driven by sustainability performance.

Companies need to adopt an approach that integrates sustainable business practices in operational decision-making and be governed by board of directors set corporate goals and strategies in accordance with the need to balance the interests of key stakeholders. Sustainable companies assign their boards the responsibility to oversee sustainability issues and establish devoted committees committed to sustainability-related tasks (Salvioni et al. 2016). Our findings have implications from the governance perspective; it sends out a message to corporate boards to explicitly embrace the proposition that sustainability is a core indicator of CEO’s responsibilities and performance.

From a regulatory perspective, policymakers could consider issuing guidelines for compensation committees to develop compensation policies with assured sustainable targets. This might better align executive incentives with sustainability, improve sustainable performance and reduce pressures to maximise short-term performance. The success of such initiatives however will depend, inter-alia, on the disclosure of credible sustainability-related information. Our findings may help to inform regulators of the importance of the sustainability assurance process and the role of governed sustainability information on top management pay and in promoting sustainable behaviour.

The United Nation Principles for Responsible Investment (UNPRI 2012) released guidance in June 2012 for the integration of environmental, social and governance issues in executive pay addressing three main areas of building compensation packages that successfully utilise sustainability metrics: (i) identifying sustainability metrics for each company; (ii) linking these metrics to executive compensation plan; and (iii) providing high-quality disclosure on sustainability compensation terms. Our study has implications from the financial statement analysis perspective; it requires companies to voluntarily report and integrate sustainability into financial statement and to demand independent external assurance over sustainability reports to enhance the quality of reporting. Finally, from an ethical perspective, companies that proactively make sustainability core to their business strategy are likely to stimulate loyalty from employees, customers, suppliers, communities and investors, enhance their reputation and create value for all stakeholders, including shareholders, employees, civil society and the planet.

Notes

The assurance of sustainability reporting, which is not mandatory in the UK, is generally conducted by accounting or specialist firms in accordance with GRI guidelines. Due to the questionable quality of sustainability reporting, assurance from a third party can help validate sustainability reporting.

Both studies rely on annual reports and proxy statements to determine the use of targets related to sustainability in executive compensation.

The study identifies environmental-friendly firms as the ones who receive high ratings in the SiriPro database, an environmental index which combines firms’ environmental commitment and performance in a single measure. The database is assembled by Sustainable Investment Research International (SIRI) Company.

The level of country environmental regulations includes regulation standards on air pollution, water, toxic waste and chemicals, flexibility, subsidisation and the strictness of regulation enforcement. The findings of most cross-country studies on social performance and executive compensation may be affected by the institutional context, in particular maturity of environmental legislation and corporate governance requirements.

A 2013 joint report by the Investor Responsibility Research Centre and Sustainable Investments Institute shows that a 43% of Fortune 500 Firms link executive pay to sustainability issues (Patterson 2013).

NGOs concerned with SRA in the UK include inter-alia AccountAbility, the International Audit Assurance Standards Board (IAASB) and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (corporateRegister.com).

Néron (2010) also refers to this complexity of standards and practitioners as the ‘politics of accountability’.

We have balanced data in our panel data set. A balanced data set is a set that contains all elements observed in all time frames, whereas unbalanced data are a set of data where in certain years the data category is not observed. Using a balanced panel may lead to cutting observations. However, the power of a balanced or equal-allocation design is typically higher than the power of the corresponding unbalanced design.

The Asset4 database which has already been used in the literature (see for e.g. Eccles et al. 2014; Cheng et al. 2014; Ioannou and Serafeim 2012; Birkey et al. 2016; Haque 2017), provides objective, relevant and systematic environmental, social and governance (ESG) information based on key performance indicators. Research analysts of ASSET4 collect data from sources including stock exchange filings, annual financial and sustainability reports, nongovernmental organizations’ websites and various news sources (Eccles et al. 2014).

We identify companies incentivising sustainable behaviour, and we analyse the descriptions of non-financial performance to code the compensation as sustainability-linked. The most common descriptions are: performance targets in relation to sustainability; the role of compensation committee in determining non-financial performance targets in consultation with sustainability committee; remuneration is linked to strategic objectives and risk management and its alignment with shareholders’ interests including the maintenance of health, safety and environmental risks; regulatory compliance with ethical standards and approach to risks (including environmental, social and governance risks); percentage of non-financial targets included in companies’ annual incentive plan.

Companies differ in the specific title they assign to the board subcommittee dealing with sustainability reporting matters, e.g. corporate social responsibility committee, health and safety and environmental affairs committee.

We rely on Industry Classification Benchmark (ICB) sector codes level 3 in our classification of firms into sensitive and non-sensitive sectors.

Untabulated tests using SRAProvidert−1 as a measure of SRAt−1 show that SUSCOMt−1 is significant and positively associated with SUSCONTRACTINGt and SRAProvidert−1 is positively associated with SUSCONTRACTINGt but is insignificant.

All tests use panel data fixed effects with robust standard errors where Hausman tests confirm this as the correct specification. The fixed effects model cannot take time-invariant dummy variables, so industry dummies in this case are omitted, since the fixed effect model explains the portion of variance given by the distance between each observation and the individual mean (computed as zero for time-invariant dummies).

It is important to check the validity of the IV approach; otherwise, it could lead to biased results. If the test of endogeneity finds that SRA is endogenous, OLS estimation, in which the specified endogenous regressors cannot be treated as exogenous, is inappropriate as a test methodology and an IV approach is required (Cornett et al. 2009).

Using SUSCONTRACTINGt as dependent, our Durbin (p = 0.678) and Wu-Hausman (0.680) tests found that the p value is insignificant. Using CEOCOMt as dependent variable, our Durbin (p = 0.111) and Wu-Hausman (0.087) tests found that the p value is insignificant; using SALARYt as the dependent, our Durbin (p = 0.134) and Wu-Hausman (0.132) tests found that the p value is insignificant; using BONUSt as the dependent, our Durbin (p = 0.981) and Wu-Hausman (0.982) tests found that the p value is insignificant; using LTCOMt as the dependent, our Durbin (p = 0.608) and Wu-Hausman (0.611) tests found that the p value is insignificant, thus suggesting that SRAt−1 is exogenous.

According to Heckman (1976), endogeneity refers to the fact that an independent variable included in the model is potentially a choice variable, correlated with unobserved factors relegated to the error term, while the dependent variable is observed for all observations in the sample (Jo and Harjoto 2012).

We consider SRA as the binary outcome of the selection equation and CEO compensation as the outcome of the main equation.

Since the sample selection bias is not present, there is no need to include the inverse Mills ratios in our regression tests.

We use the following model: SRAt = α+β1SUSCONTRACTINGt + β2SUSCOMt + β3BODSIZEt + β4BODINDt + β5BODMEETt + β6BODEXPt + β7CEOOWNt + β8SIZEt + β9ROEt + β10LEVt + β11TOBINSQt +β12BETAt +β13IND + εit.

We followed prior literature in building our specification model (see Simnett et al. 2009; Herda et al. 2014; Martínez-Ferrero and García-Sánchez 2017) on the determinants of sustainability reporting assurance. These papers do not apply lagging to the right-hand side variable of their models. However, we also run the test by regressing SRA on lagged independent variables and find SUSCONTRACTINGt−1 is positive and marginally significant, and BODSIZEt−1, BODMEETt−1 and BODEXPt−1 are positive and significant with SRAt. Our results show that providing references to sustainability-related targets in CEO compensation contract disclosed in companies’ annual reports in year t will lead to acquiring assurance in year t, while it is not very likely for the following year.

References

Baron, D. P. (2008). Managerial contracting and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Public Economics, 92(1), 268–288.

Bebchuk, A. L., & Fried, J. M. (2003). Executive compensation as an agency problem. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(3), 71–92.

Benson, B. W., & Davidson, W. N. (2010). The relation between stakeholder management, firm value, and CEO compensation: A test of enlightened value maximization. Financial Management, 39(3), 929–964.

Berrone, P., & Gomez-Mejia, L. R. (2009a). Environmental performance and executive compensation: An integrated agency-institutional perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 52(1), 103–126.

Berrone, P., & Gomez-Mejia, L. R. (2009b). The pros and cons of rewarding social responsibility at the top. Human Resource Management, 48(6), 959–971.

Birkey, R. N., Michelon, G., Patten, D. M., & Sankara, J. (2016). Does assurance on CSR reporting enhance environmental reputation? An examination in the US context. Accounting Forum, 40(3), 143–152.

Brown-Liburd, H., & Zamora, V. L. (2014). The role of corporate social responsibility (CSR) assurance in investors’ judgments when managerial pay is explicitly tied to CSR performance. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, 34(1), 75–96.

Burchman, S., & Sullivan, B. (2017, August). Tie executive compensation to sustainability. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from: https://hbr.org/2017/08/its-time-to-tie-executive-compensation-to-sustainability.

Cai, Y., Jo, H., & Pan, C. (2011). Vice or virtue? The impact of corporate social responsibility on executive compensation. Journal of Business Ethics, 104(2), 159–173.

Callan, S. J., & Thomas, J. M. (2011). Executive compensation, corporate social responsibility, and corporate financial performance: A multi-equation framework. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 18(6), 332–351.

Callan, S. J., & Thomas, J. M. (2014). Relating CEO compensation to social performance and financial performance: Does the measure of compensation matter? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 21(4), 202–227.

Cheng, M., Green, W., & Ko, J. (2012). The impact of sustainability assurance and company strategy on investors’ decisions. Australian Accounting Review, 2(1), 58–74.

Cheng, B., Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2014). Corporate social responsibility and access to finance. Strategic Management Journal, 35(1), 1–23.

Chung, K. H., & Pruitt, S. W. (1994). A simple approximation of Tobin’sQ. Financial Management, 23, 70–74.

Cohen, J. R., & Simnett, R. (2014). CSR and assurance services: A research agenda. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, 34(1), 59–73.

Collett Miles, P., & Miles, G. (2013). Corporate social responsibility and executive compensation: Exploring the link. Social Responsibility Journal, 9(1), 76–90.

Coombs, J. E., & Gilley, K. M. (2005). Stakeholder management as a predictor of CEO compensation: Main effects and interactions with financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 26(9), 827–840.

Cordeiro, J. J., & Sarkis, J. (2008). Does explicit contracting effectively link CEO compensation to environmental performance? Business Strategy and the Environment, 17(5), 304–317.

Cornett, M. M., McNutt, J. J., & Tehranian, H. (2009). Corporate governance and earnings management at large US bank holding companies. Journal of Corporate Finance, 15(4), 412–430.

CorporateRegister.com. (2008). Assure view: The CSR assurance statement report. London: CorporateRegister.com Limited.

Daily, C. M., Dalton, D. R., & Rajagopalan, N. (2003). Governance through ownership: Centuries of practice, decades of research. Academy of Management Journal, 46(2), 151–158.

Davila, A., & Venkatachalam, M. (2004). The relevance of non-financial performance measures for CEO compensation: Evidence from the airline industry. Review of Accounting Studies, 9(4), 443–464.

Deckop, J. R., Merriman, K. K., & Gupta, S. (2006). The effects of CEO pay structure on corporate social performance. Journal of Management, 32(3), 329–342.

Deegan, C., & Gordon, B. (1996). A study of the environmental disclosures practices of Australian corporations. Accounting and Business Research, 26(3), 187–199.

Deegan, C., & Islam, M. A. (2012). Corporate Commitment to Sustainability–Is it All Hot Air? An Australian Review of the Linkage between Executive Pay and Sustainable Performance. Australian Accounting Review, 22(4), 384–397.

Denis, D. K. (2001). Twenty-five years of corporate governance research and counting. Review of Financial Economics, 10(3), 191–212.

Dixon, R., Mousa, G. A., & Woodhead, A. D. (2004). The necessary characteristics of environmental auditors: A review of the contribution of the financial auditing profession. Accounting Forum, 28(2), 119–138.

E&Y. (2010). Seven things CEOs and boards should ask about triple-bottom-line reporting. AICPA Sustainability Initiative Resource Review.

Eccles, R. G., Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2014). The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Management Science, 60(11), 2835–2857.

Fernandez-Feijoo, B., Romero, S., & Ruiz, S. (2014). Effect of stakeholders’ pressure on transparency of sustainability reports within the GRI framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 122(1), 53–63.

Financial Reporting Council. (2016). The UK Corporate Governance Code. London: FRC.

Finkelstein, S. (1992). Power in top management teams: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 35(3), 505–538.

Francoeur, C., Melis, A., Gaia, S., & Aresu, S. (2017). Green or greed? An alternative look at CEO compensation and corporate environmental commitment. Journal of Business Ethics, 140(3), 439–453.

Frye, M. B., Nelling, E., & Webb, E. (2006). Executive compensation in socially responsible firms. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 14(5), 446–455.

Glass Lewis (2016) In-depth: Linking compensation to sustainability. Retrieved from: http://www.glasslewis.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/2016-In-Depth-Report-LINKING-COMPENSATION-TO-SUSTAINABILITY.pdf.

Gomez-Mejia, L., & Wiseman, R. M. (1997). Reframing executive compensation: An assessment and outlook. Journal of Management, 23(3), 291–374.

Gray, R. (2000). Current developments and trends in social and environmental auditing, reporting and attestation: A review and comment. International Journal of Auditing, 4(3), 247–268.

EY & GreenBiz Group (2013) Six growing trends in corporate sustainability. Retrieved form: http://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/Six_growing_trends_in_corporate_sustainability_2013/$FILE/Six_growing_trends_in_corporate_sustainability_2013.pdf.

Greene, W. (1993). Econometric analysis (5th ed.). Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Haque, F. (2017). The effects of board characteristics and sustainable compensation policy on carbon performance of UK firms. The British Accounting Review, 49(3), 347–364.

Heckman, J. J. (1976). The common structure of statistical models of truncation, sample selection and limited dependent variables and a simple estimator for such models. Annals of Economic and Social Measurement, 5(4), 475–492.

Heckman, J. (1979). Sample selection as a specification error. Econometrica, 47, 153–161.

Herda, D. N., Taylor, M. E., & Winterbotham, G. (2014). The effect of country-level investor protection on the voluntary assurance of sustainability reports. Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting, 25(2), 209–236.

Hermalin, B. (2005). Trends in corporate governance. Journal of Finance, 60(5), 2351–2384.

Hodge, K., Subramaniam, N., & Stewart, J. (2009). Assurance of sustainability reports: Impact on report users’ confidence and perceptions of information credibility. Australian Accounting Review, 19(3), 178–194.

Hong, B., Li, Z., & Minor, D. (2015). Corporate governance and executive compensation for corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 1(1), 1–15.

Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2012). What drives corporate social performance? The role of nation-level institutions. Journal of International Business Studies, 43(9), 834–864.

Jo, H., & Harjoto, M. A. (2012). The causal effect of corporate governance on corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 106(1), 53–72.

Junior, R. M., Best, P. J., & Cotter, J. (2014). Sustainability reporting and assurance: A historical analysis on a world-wide phenomenon. Journal of Business Ethics, 120(1), 1–11.

Knechel, W. R., Wallage, P., Eilifsen, A., & Van Praag, B. (2006). The demand attributes of assurance services providers and the role of independent accountants. International Journal of Auditing, 10(2), 143–162.

Kolk, A., & Perego, P. (2014). Sustainable bonuses: Sign of corporate responsibility or window dressing? Journal of Business Ethics, 119(1), 1–15.

KPMG. (2008). Global audit committee survey, KPMG’s Audit Committee Institute.

KPMG. (2010). Global audit committee survey, KPMG’s Audit Committee Institute.

Maas, K. (2015). Do corporate social performance targets in executive compensation contribute to corporate social performance? Journal of Business Ethics, 1–13.

Maas, K., & Rosendaal, S. (2016). Sustainability targets in executive remuneration: Targets, time frame, country and sector specification. Business Strategy and the Environment, 25(6), 390–401.

Mahoney, L. S., & Thorn, L. (2005). Corporate social responsibility and long-term compensation: Evidence from Canada. Journal of Business Ethics, 57(3), 241–253.

Mahoney, L. S., & Thorn, L. (2006). An examination of the structure of executive compensation and corporate social responsibility: A Canadian investigation. Journal of Business Ethics, 69(2), 149–162.

Martínez-Ferrero, J., & García-Sánchez, I. M. (2017). Sustainability assurance and assurance providers: Corporate governance determinants in stakeholder-oriented countries. Journal of Management & Organization, 23(5), 647–670.

McGuire, J., Dow, S., & Argheyd, K. (2003). CEO incentives and corporate social performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 45(4), 341–359.

Michelon, G., & Parbonetti, A. (2012). The effect of corporate governance on sustainability disclosure. Journal of Management and Governance, 16(3), 477–509.

Moffitt, R. A. (1999). New developments in econometric methods for labor market analysis. Handbook of Labor Economics, 3(1), 1367–1397.

Moroney, R., Windsor, C., & Aw, Y. T. (2012). Evidence of assurance enhancing the quality of voluntary environmental disclosures: An empirical analysis. Accounting & Finance, 52(3), 903–939.

Moser, D. V., & Martin, P. R. (2012). A broader perspective on corporate social responsibility research in accounting. The Accounting Review, 87(3), 797–806.

Murphy, K. (1999). Executive compensation. In O. Ashenfelter & D. Card (Eds.), Handbook of labor economics (Vol. 3). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Néron, P. Y. (2010). Business and the polis: What does it mean to see corporations as political actors? Journal of Business Ethics, 94(3), 333–352.

O’Connell, V., & O’Sullivan, D. (2014). The influence of lead indicator strength on the use of nonfinancial measures in performance management: Evidence from CEO compensation schemes. Strategic Management Journal, 35(6), 826–844.

O’Dwyer, B., & Owen, D. L. (2005). Assurance statement practice in environmental, social and sustainability reporting: A critical evaluation. The British Accounting Review, 37(2), 205–229.

Patten, D. M. (1991). Exposure, legitimacy, and social disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 10(4), 297–308.

Patten, D. M. (2002). Media exposure, public policy pressure, and environmental disclosure: An examination of the impact of tri data availability. Accounting Forum, 26(2), 152–171.

Patterson, K. (2013). Top companies tie compensation to sustainability. CSRHUB, retrieved form http://www.csrhub.com/blog/2013/05/top-companies-tie-compensation-to-sustainability.html.

Peters, G. F., & Romi, A. M. (2014). The association between sustainability governance characteristics and the assurance of corporate sustainability reports. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, 34(1), 163–198.

Post, C., Rahman, N., & Rubow, E. (2011). Green governance: Boards of directors’ composition and environmental corporate social responsibility. Business and Society, 50(1), 189–223.

Riahi-Belkaoui, A. (1992). Executive compensation, organizational effectiveness, social performance and firm performance: An empirical investigation. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 19(1), 25–38.

Romero, S., Ruiz, S., & Fernández-Feijóo, B. (2010). Assurance Statement for Sustainability Reports: The Case of Spain. Proceedings of the Northeast Business & Economics Association.

Ruhnke, K., & Gabriel, A. (2013). Determinants of voluntary assurance on sustainability reports: An empirical analysis. Journal of Business Economics, 83(9), 1063–1091.

Salvioni, D. M., Gennari, F., & Bosetti, L. (2016). Sustainability and convergence: The future of corporate governance systems? Sustainability, 8(11), 1203.

Schiehll, E., & Bellavance, F. (2009). Boards of directors, CEO ownership, and the use of non-financial performance measures in the CEO bonus plan. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 17(1), 90–106.

Simnett, R., Vanstraelen, A., & Chua, W. F. (2009). Assurance on sustainability reports: An international comparison. The Accounting Review, 84(3), 937–967.

Smith, J., Haniffa, R., & Fairbrass, J. (2011). A conceptual framework for investigating ‘capture’ in corporate sustainability reporting assurance. Journal of Business Ethics, 99(3), 425–439.

Stanwick, P. A., & Stanwick, S. D. (1998). The determinants of corporate social performance: An empirical examination. American Business Review, 16(1), 86–93.

Stanwick, P. A., & Stanwick, S. D. (2001). CEO compensation: Does it pay to be green? Business Strategy and the Environment, 10(1), 176–182.

Tonello, M., & Singer, T. (2015). Sustainability practices 2015 key findings. The Conference Board, INC.

Trotman, A. J., & Trotman, K. T. (2015). Internal audit’s role in GHG emissions and energy reporting: Evidence from audit committees, senior accountants, and internal auditors. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 34(1), 199–230.

Ullmann, A. A. (1985). Data in search of a theory: A critical examination of the relationships among social performance, social disclosure, and economic performance of US firms. Academy of Management Review, 10(3), 540–557.