Abstract

Framed within theories of fairness and stress, the current paper examines bystanders’ intervention intention to workplace bullying across two studies based on international employee samples (N = 578). Using a vignette-based design, we examined the role of bullying mode (offline vs. online), bullying type (personal vs. work-related) and target closeness (friend vs. work colleague) on bystanders’ behavioural intentions to respond, to sympathise with the victim (defender role), to reinforce the perpetrator (prosecutor role) or to be ambivalent (commuter role). Results illustrated a pattern of the influence of mode and type on bystander intentions. Bystanders were least likely to support the victim and more likely to agree with perpetrator actions for cyberbullying and work-related acts. Tentatively, support emerged for the effect of target closeness on bystander intentions. Although effect sizes were small, when the target was a friend, bystanders tended to be more likely to act and defend the victim and less likely to reinforce the perpetrator. Implications for research and the potential for bystander education are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bullying at work has been most frequently defined as a series of persistent and repeated negative actions that are directed at individuals who have difficulties in defending themselves (Einarsen et al. 2003). An emerging and comparatively under-researched threat at work is that of cyberbullying, with interpersonal hostility via email increasingly being recognised as a growing problem within the workplace (Shipley and Schwalbe 2007; Weatherbee and Kelloway 2006). Cyberbullying at work has been defined as:

“a situation where over time, an individual is repeatedly subjected to perceived negative acts conducted through technology (e.g., phone, email, web sites, social media) which are related to their work context. In this situation the target of workplace cyberbullying has difficulty defending him or herself against these actions” (Farley et al. 2016, p. 295).

Serious negative consequences of offline bullying have been identified in the literature, including severe effects on victims’ job satisfaction, stress and health (Nielsen et al. 2010), as well as psychological effects under the domain of post-traumatic stress disorder (Coyne 2011). Similarly, cyberbullying has been shown to negatively affect victims; including anxiety, job dissatisfaction, intention to leave and general well-being (Baruch 2005; Coyne et al. 2017; Ford 2013).

Currently, scholars diverge on whether workplace cyberbullying is simply bullying using technology (Coyne et al. 2017) or is conceptually distinct from offline bullying (Vranjes et al. 2017). Vranjes et al. argue for a conceptually distinct notion focus because of unique features of cyberbullying such as the lack of verbal cues, potential for anonymity, blurring of the public–private boundary and the viral reach of online communication. By contrast, other scholars maintain that it is a form of bullying (e.g. Campbell 2005) albeit with the unique features resulting in more detrimental effects for victims, as victims cannot escape the abuse. Coyne et al. (2017) support this idea illustrating stronger relationships to mental strain and job dissatisfaction for online as compared to offline bullying. Cyberbullying has the potential to permeate a larger part of an individual’s life resulting in an inability to psychologically detach from the event therefore not allowing the victim to switch off from the stressor (Moreno-Jiménez et al. 2009).

Recently, there has been a growing interest in research around the role of bystanders in bullying (Nickerson et al. 2008). Bystanders are people who witness bullying but are not involved directly as bully or target. Such individuals may not necessarily be ‘passive observers’ (van Heugten 2011), as bystanders can discourage or escalate the bullying behaviours by speaking up on the victim’s behalf, or supporting the bully either actively or passively (Lutgen-Sandvik 2006). With few exceptions (Bloch 2012; Coyne et al. 2017; Lutgen-Sandvik 2006; van Heugten 2011), bystanders in the context of workplace bullying/cyberbullying are relatively unexplored to date (Paull et al. 2012). Yet, bystanders are by far the largest group affected by workplace bullying with some studies finding that more than 80% of employees report having witnessed workplace bullying (Lutgen-Sandvik 2006) and others indicating witnessing workplace bullying resulted in stress (Hoel et al. 2004; Vartia 2001).

To address the current limited empirical research in bystander intervention in workplace bullying and cyberbullying, our research details two related quasi-experimental studies with a total sample of 578 working individuals. We adopt perspectives from fairness theory and stress theory to help frame the research and to develop hypotheses on the impact of mode and type of bullying as well as closeness of target on bystander behaviour.

Bystanders in Workplace Bullying

Critically, the extant research in workplace bullying often considers it as a dyadic conflict between victim and bully which oversimplifies the communal nature of the concept. Namie and Lutgen-Sandvik (2010) provided evidence that the majority of bullying incidents involve many workers (including bystanders and accomplices) beyond the bully and the victim. Yet, bullying research often fails to consider the role witnesses play in the occurrence, escalation or attenuation of workplace bullying.

Jennifer et al. (2003) put forward the interesting notion that bullies do not merely target one victim, but scout the organisation for potential victims from among a pool of non-victims who “fill the gap whenever ‘vacancies’ arise” (p. 495). Witnesses play a critical role in highlighting bullying in organisations and helping victims to retaliate. Witness corroboration and support increases victim ‘believability’, and can be crucial in putting a stop to bullying episodes (Lutgen-Sandvik 2006). However, D’Cruz and Noronha (2011) reported bystander behaviour to offline bullying ranged on a helpful to a helplessness continuum. While initially active behaviour was focused on helping the target, due to supervisor responses actions became more passive and covert. Further, a number of studies document that a large deterrent for bystander intervention in an organisation is fear of becoming a target oneself (Bauman and Del Rio 2006; Lutgen-Sandvik 2006; Namie and Lutgen-Sandvik 2010; van Heugten 2011).

Research into bystander intervention in workplace bullying is pertinent for a number of reasons. Firstly, bystanders may play a more important role than supervisors because as they tend to outnumber supervisors, they can react immediately to bullying acts and co-workers are more likely to confide in them (Scully and Rowe 2009). Bystanders are therefore likely to be the first individuals who can report the bullying or discourage/escalate bullying behaviours before supervisors are aware of the situation.

Secondly, based on findings from social psychology, potentially witnesses, by the roles they play and their actions or inaction, can influence the way negative acts, such as bullying and harassment, are perceived and carried out (Levine et al. 2002). Witnesses can play a crucial role in curbing bullying. They can expose its existence in organisations and can also help victims in various ways such as providing social support, standing up to the bullies or speaking out on a victim’s behalf (Lutgen-Sandvik 2006).

Thirdly, research has argued that bystanders’ responses (e.g. adopting a defender, prosecutor or commuter role) to bullying episodes may range widely according to their perception of the situation and who is to blame for the occurrence of bullying (Bloch 2012).

Theoretical Framework

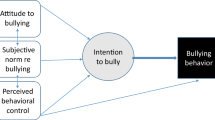

Robinson et al. (2014) offer three approaches to understanding bystanders’ experiences of co-worker deviant behaviour: deontic justice (Folger and Skarlicki 2005), stress perspectives (e.g. Glomb et al. 1997) and social learning theory (Bandura 1977). Theoretically, our research adopts the deontic justice and stress perspectives as frameworks to examine bystander intervention intention in workplace bullying.

Folger and Skarlicki (2005) suggest that individuals compare the fairness of their current experience with a referent alterative through a blame assignment process based on judgements of what would, should and could have happened. Underlying this process is an individual’s level of moral responsibility which relates to perceptions of the adversity of the experience and beliefs that the perpetrator can be held morally accountable for his/her behaviour. An individual is motivated to act and hold someone accountable if behaviour is perceived as a moral violation—deontic justice. Parzefall and Salin (2010) apply deontic justice to workplace bullying contexts, theorising that perception of fairness of an act depends on whether the target believes the perpetrator could and should have avoided the behaviour, which in turn dictates whether a behaviour is seen as bullying or not.

Deontic justice does not only apply to the target of mistreatment as witnesses of negative treatment have also been shown to be motivated to act (Fehr and Fischbacher 2004; Skarlicki and Rupp 2010). Specifically, bystanders who have empathy with a recipient care about the injustices the recipient experiences (Patient and Skarlicki 2010). O’Reilly and Aquino (2011) suggest witnesses perform the same three cognitive appraisals as a target of negative behaviour: the severity of harm in terms of what would be expected if the target did not face the behaviour; the attribution of blame to perpetrator if she/he could have acted differently; and the extent the target deserved to experience the behaviour based on social norm judgements of what should happen. Unfairness perceptions and deontic anger will increase if acts are deemed severe, the perpetrator was to blame, and the victim did not deserve it. Empirically, witnesses of workplace bullying are driven to act because of a moral obligation to do so (Lutgen-Sandvik 2006) and motivated to restore justice when they perceived it as a moral violation (Reich and Hershcovis 2015). Consequently, deontic justice could help explain bystander behaviour in relation to workplace bullying and cyberbullying. We would expect a bystander to perceive bullying as morally unjust resulting in deontic anger and motivation to respond.

However, Mitchell et al. (2015) argue witness fairness perceptions of abusive supervision will not always result in deontic anger—especially when they exhibit negative evaluations towards the target of the abuse. Explicitly, bystander emotional reactions to abuse dictate specific action tendencies of retaliation to the transgressor, support for the target or exclusion of the target. Similarly, within a bullying context, Bloch (2012) posited witnesses construct a moral schema of the bullying incident that determines their attribution of who is to blame and to whom to attribute the responsibility for the occurrence of bullying. On occasions when witnesses perceive the victim’s actions and behaviour being within the social norms of the workplace, and consequently the bully’s behaviour as deviant, witnesses are likely to adopt the ‘defender role’, in which they stand up to the bully on behalf of the victim. In contrast, in the ‘prosecutor role’, the victim is viewed as the deviant in terms of the moral or occupational norms of the workplace and the cause of his/her own difficulties. Finally, witnesses who adopt the ‘commuter role’ alternate between looking on the victim as normal or deviant, and thus this schema involves feelings of ambivalence and doubt regarding who is to blame and who to ‘side with’. Thus, witnesses fluctuate between sympathising with the victim and conforming to the assessment of the victim as deviant.

Our research also integrates notions of bystander stress with bystander fairness perceptions, emotions and action tendencies. Witnesses of negative workplace behaviour are viewed as secondary victims or co-victims (Glomb et al. 1997), who empathise with how the target is feeling and experience some of the impact or exhibit concerns about being the next target (Porath and Erez 2009). In effect they put themselves psychologically in the position of the target and hence experience some of the strain of the target. As a result, witnesses will be motivated to reduce their felt stress. Empathy with the target is important in establishing this felt experience, and empathy has been shown to relate to the type of schema a witness of traditional workplace bullying adopts. Those adopting a victim defender schema tend to express: “…empathy and emotions that allow for the formation of social bonds with the victim” (Bloch 2012, p. 87). Empathy has previously been suggested to relate to consideration about injustices an individual may face (Patient and Skarlicki 2010). Theoretically, bystander perceptions of the fairness of bullying may depend on the level of empathy with the target and the resultant co-victimisation they experience. The more an individual empathises with a target, the more likely they will become a secondary victim and the stronger the need to act.

Perceptions of injustice and empathic understanding could therefore be moderated by features of the bullying situation. The three we focus on in this paper are mode and type of bullying (Study 1) and closeness of target (Study 2).

Study 1

Bystander Behaviour Online Versus Offline

Li et al. (2012, p. 8) posit that: “The variety of bystander roles in cyberbullying is more complex than in most traditional bullying”. Viewing an abusive message online is considered as taking part even if the bystander privately disagrees (Macháčková et al. 2013). Some have argued that cybercontexts result in “…less opportunity for bystander intervention” (Slonje and Smith 2008, p. 148). Behaviourally, bystanders are less likely to actively intervene (Barlińska et al. 2013) and more likely to join in the behaviour given the anonymity and depersonalisation in online versus offline bullying (Kowalski et al. 2012).

Cyberbullying may be described as more covert and ‘behind the scenes’ than offline bullying (Spears et al. 2009), which has possible implications for bystanders’ perceptions of the fairness of the bullying and willingness to assist victims. Misunderstandings between sender and receiver are more likely in online communication, since it lacks the facial and body language cues that are normally used in face-to-face expression (Suler 2004). These cues play an important role in the process of automatic activation of empathy, and their absence can lead to increased levels of aggression and a greater chance of disinhibited behaviours (Ang and Goh 2010). As a result, a deindividuation effect occurs, making people less sensitive to the thoughts and feelings of others (Siegel et al. 1986). The process of deindividuation may also cause a bystander to exhibit less empathic understanding towards the actual target. As previously suggested within a stress perspective, when a person witnesses bullying, they imagine how the victim is feeling and consequently experiences some of the bullying impact (Porath and Erez 2009). Coyne et al. (2017) suggest bystanders of cyberbullying do not necessarily put themselves psychologically in the position of the target and therefore do not develop strong emotional empathy with the target. As a result, they are less likely to experience bystander stress and hence are not pressured to act to reduce such stress.

Additionally, the covert nature of some forms of cyberbullying may cause difficulty for bystanders in identifying behaviours (Escartín et al. 2013). The subtle, ambiguous, and easily misinterpreted nature to online bullying behaviours could result in bystanders doubting whether a target is actually facing bullying (Samnani 2013). Ambiguous behaviours might also not be perceived as important enough to promote bystander intervention (Reich and Hershcovis 2015). As a result perceptions of deontic justice and moral accountability could be lessened, limiting positive bystander intervention.

Thus it is possible that online cyberbullying may be more ambiguous to bystanders, in turn reducing the likelihood of them to intervene. The blame attributions emerging from the ‘would’, ‘could’ and ‘should’ cognitions could result in bystander perceptions that the act was not severe (e.g. not bullying), the perpetrator was not to blame and the target deserved it. Coupled with the fact that emotions are particularly difficult to accurately communicate and perceive via email (Byron 2008) and messages via email may increase the potential for misinterpretation (Giumetti et al. 2012) empathic understanding may be reduced.

Additionally, as discussed, perceptions of fairness and empathic understanding may also impact on the role a bystander adopts when witnessing workplace bullying/cyberbullying. Differences in attributions of blame deriving from a moral schema, results in whether a bystander adopts a defender, prosecutor or commuter role (Bloch 2012). Consequently, if cognitions of deontic justice and moral outrage differ as a result of the mode of bullying, then bystanders are likely to adopt different roles depending on the nature of the bullying. Additionally, Bloch suggests bystanders are more likely to adopt a defender role when experiencing empathy with the target. Our first set of hypotheses examines the impact of mode of bullying on bystander role:

Hypothesis 1a

Bystander intentions to intervene will be influenced by whether the mode of bullying is online or offline

Hypothesis 1b

Bystanders’ likelihood of adopting the defender, prosecutor and commuter role will be influenced by whether the mode of bullying is online or offline

Bystander Behaviour and Type of Bullying

Bauman and Del Rio (2006) found that teachers were significantly less likely to intervene, show sympathy to victims or punish bullies in relational bullying (social ostracism) than physical and verbal bullying. They suggest this may be due to the subtlety of relational bullying, as opposed to physical where it is clear that bullying is occurring and there are clear operating guidelines against physical violence. At work, there is considerable scope for subtle and covert tactics of leadership that can lead to ambiguity in terms of the attributions of the witnesses (Leymann 1990), and specific scenarios that are perceived to warrant intervention may not be as easily identifiable as in other bystander studies (Ryan and Wessel 2012). Consequently, many incidents of work-related bullying can be misinterpreted as strong or negative management (Simpson and Cohen 2004). Additionally, work-related acts are seen as more acceptable than personal abuse (Escartín et al. 2009) and physical bullying across cultures (Power et al. 2013), and more subtle by human resource professionals (Fox and Cowan 2014). The type of behaviour could minimise perceptions of injustice towards the target and moral accountability of the perpetrator resulting in a lack of moral outrage towards the behaviour and lower motivation to act. A bystander could perceive the victim is not suffering (hence reduce empathic understanding) and be less likely to support the victim (Samnani 2013). Along similar lines to that espoused for mode of bullying, type of bullying may also relate to bystanders’ adoption of a specific role through its impact on perceived fairness and empathic understanding.

Hypothesis 2a

Bystanders intention to intervene will be influenced by whether the type of bullying is work-related or personal.

Hypothesis 2b

Bystanders likelihood of adopting the defender, prosecutor and commuter role will be influenced by whether the type of bullying is work related or personal.

Privitera and Campbell (2009) found targets can experience both work-related and personal bullying in both online and offline modes. The possible ambiguity of work-related and online bullying behaviour and the potential for increased misinterpretation of online communication due to reduced social cues may have an interactive effect. As such, the higher ambiguity of work-related cyberbullying and the potential this may have for empathy may decrease the likelihood of bystander intervention and adoption of the defender role. Our next hypotheses are:

Hypothesis 3a

Bystander intervention intention will be influenced by the interaction between mode and type of bullying.

Hypothesis 3b

Bystanders’ likelihood of adopting the defender, prosecutor and commuter role will be influenced by the interaction between mode and type of bullying.

Method

Measures and Procedure

Vignettes were designed to simulate a within-participants experimental manipulation (see “Appendix 1”) so that all participants were presented with scenarios of all four combinations of type (personal vs. work-related) and mode (online vs. offline). Vignettes have been found to better estimate real-life decision-making than interviews or questionnaires (Alexander and Becker 1978) and are an appropriate method for broaching sensitive issues since participants’ responses based on personal experience are not required (Wilks 2004). Vignette questionnaires have been successfully used in previous (cyber)bullying research (Bastiaensens et al. 2014; Bauman and Del Rio 2006). Vignettes were chosen over computer laboratory designs (e.g. Barlińska et al. 2013; Giumetti et al. 2013) because these designs do not capture fully the key definitional criteria of frequency and duration required for an act to be considered workplace bullying. Both studies only manipulate the negative behaviour once via pairing an image or task with a single negative peer (Barlińska et al.) or supervisor message (Giumetti et al.). As a result, the bystander only witnesses an initial response to the incident and not one which has some feature of frequency and duration. Further, Hershcovis (2011) criticises robustly the measurement of offline bullying and the proliferation of similar concepts each with differing definitional criteria (e.g. incivility, social undermining, bullying, and abusive supervision). Her thesis is that while these concepts espouse different criteria (such as frequency, power, low level, non-physical), their measurement tends to neglect to include these criteria. We were therefore concerned not to follow this pattern and to ensure our measurement captured bullying and not related concepts such as incivility.

Bullying behaviours exhibited in the scenarios were generated using examples of personal and work-related negative acts from the Negative Acts Questionnaire (NAQ-R) (Einarsen et al. 2009). We examined the NAQ-R and identified those behaviours seen as work-related and personal. Additionally, we consulted research by Farley et al. (2016) on an adapted version of the NAQ for use in cybercontexts to establish those acts which could also be enacted online. This was to ensure that the type of negative act included within scenarios was held constant across offline and online contexts. The online manipulation was restricted to email abuse because we wanted to control for potential effects of different online media on bystander intentions and also because email has tended to be the focus of the limited workplace cyberbullying research so far (e.g. Baruch 2005; Ford 2013). Bullying scenarios were then created through a number of iterations combining acts from the NAQ-R focused at the personal or work level, ensuring that only the specific manipulations varied across the scenarios.

In order to ensure our behaviours mapped closely to workplace bullying definitional criteria of frequency and duration, we included a clear indication each negative act was persistent and ongoing. Additionally, to capture the criteria of power imbalance in all cases, the act was perpetrated by a supervisor on a subordinate. Gender of both victim and perpetrator was not identified.

Pre-pilot and pilot tests were completed in the development of the vignettes. At pre-pilot stage, six members of a university group, in different fields of study, were asked to read the four bullying scenarios and provide feedback regarding the comprehension level of the survey, how well they could relate to the scenarios and if sufficient information was given to answer the questions. They were then told the aims of the study and asked to consider the survey in regard to these. Based on feedback, changes in vocabulary, language usage, content and structure were made. Participants then reviewed these changes and agreed to them. Another ten participants then piloted this version of the online survey to ensure no bias effects in responses and to check its suitability for research.

To counter the criticism of Hershcovis (2011) that measures of workplace bullying do not necessarily assess intensity, we asked participants to rate the seriousness of each scenario using Bauman and Del Rio’s (2006) measure. Respondents were asked to rate how serious they thought each scenario was on a 5-point Likert scale of 1 (not serious at all) to 5 (very serious). Mean ratings ranged from 4.04 for the online work scenario to 4.52 for the offline personal scenario—suggesting that on average participants perceived the scenarios to be ‘serious’. However, significant differences in seriousness ratings were seen for mode [F(1, 104) = 17.27, p < 0.001] and type [F(1, 104) = 14.36, p < 0.001], with lower mean ratings seen for online and work-related bullying.

To counterbalance bias effects, the order of the scenarios was randomised for each different participant via the survey software. Each scenario was then followed by five 5-point Likert scale items ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), which sought to obtain information on the participant roles bystanders would likely adopt and how likely they would be to respond to the situation described.

Participant Roles

Adapting Bloch’s (2012) three main participant roles in workplace bullying, three 5-point Likert scale questions were created. For the defender role, participants responded to the question: ‘I would feel sympathetic to my co-worker’; for the prosecutor role: ‘I agree with my Supervisor’s actions’ and for the commuter role: ‘My support wavers between both my Supervisor and my co-worker’.

Likelihood to Respond

Participants were asked to what extent they agreed with the statement ‘I would respond to this situation in some way’.

Participants

The final vignettes were distributed via email and posted on a social network site, initially inviting candidates from Trinidad and Tobago who met the criteria of being currently or previously employed in an organisation to participate. The sample comprised a network of working professionals and former work colleagues of one of the researchers. In order to acquire a larger sample, this opportunity sampling was later extended to snowball sampling, in which initial participants were encouraged to forward the link to friends and colleagues. The vignettes were preceded by an information sheet which fully described participants’ rights to voluntarily provide their data confidentially. Their consent was gained before they started, and upon completion all participants were directed to a debriefing page which stated the main subject and aims of the study.

One hundred and forty-nine respondents started the vignettes. Thirty-nine (26%) were excluded from analysis as they did not complete a significant portion of scenarios. Of the remaining 110 participants, 68% were female, and 41% male. Respondents were predominantly from Trinidad and Tobago (73.6%), with 18.2% from the UK, and the remaining 8.2% participants coming from France, Barbados, Canada, Jamaica, Tanzania, UAE and Zambia. Participants’ mean age was 29.9 years (SD = 8.1), and mean job tenure was 3.5 years (SD = 4.7). Regarding job level, the sample comprised 62.9% staff, 22.7% supervisors and 13.6% managers.

Results

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for bystander intention variables from study 1. A 2 × 2 (type × mode) repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to examine the main effects of mode and type, plus the interaction between the two.

Results indicated a significant main effect of bullying mode [F (1, 99) = 9.17, p = 0.003, r = .29] and type [F (1, 99) = 9.85, p = 0.002, r = .30] on the extent participants indicated they would respond in some way. Bystanders were significantly more likely to respond in offline than online scenarios (Mdiff = .23, 95% CI [.08, .37]) and when the bullying was personal than work-related (Mdiff = .29, 95% CI [.11, .47]). There was a non-significant interaction effect between type and mode [F (1, 99) = 0.68, p = 0.411, r = .08]. Based on Cohen (1988), main effects yielded a medium effect size, with a small effect size for the interaction.

A significant main effect of bullying mode [F (1, 104) = 12.56, p = 0.001, r = .33] and type [F (1, 104) = 19.49, p < 0.001, r = .40] occurred for ratings of sympathy with the target—both effects can be construed as yielding medium effect sizes. Bystanders were significantly more likely to adopt the defender role in offline than online scenarios (Mdiff = .21, [.09, .33]) and when the bullying was personal than work-related (Mdiff = .31, [.17, .45]). There was a non-significant interaction effect between type and mode [F (1, 104) = 3.45, p = 0.066, r = .18]—yielding a small effect size.

In relation to the prosecutor role, significant main effects of mode [F (1, 101) = 31.67, p < 0.001, r = .49] and type [F (1, 101) = 131.42, p < 0.001, r = .75] as well as an interaction effect between mode and type emerged [F (1, 104) = 6.846, p = 0.01, r = .25]. Effect sizes indicate large effects of mode and type and a medium effect for the interaction. The interaction graph (Fig. 1) reveals that the increase in support for the perpetrator’s work-related bullying behaviour is greater when the behaviour is online than offline.

A significant main effect of type was seen for ratings of wavering of support between the perpetrator and target [F (1, 102) = 31.01, p < 0.001, r = .48]—a large effect size. Bystanders were significantly more likely to adopt the commuter role when the bullying was work-related than personal (Mdiff = .46, [.29, .62]). Non-significant effects emerged for mode of bullying [F (1, 102) = 2.89, p = 0.09, r = .17] and the interaction between mode and type [F (1, 102) = 1.09, p = 0.30, r = .10]. In both cases effect sizes were small.

Overall, study 1’s findings are supportive of hypotheses 1a and 2a (impact of mode and type on intervention intention) and hypotheses 1b and 2b (impact of mode and type on bystander role). No support was seen for hypothesis 3a and support for the interaction hypothesis 3b was only seen in respect of adoption of the prosecutor role.

Study 2: Bystander Behaviour and Relationship to Victim

Study 1 used a snowball sampling approach and while providing data on employed individuals; participants were distributed across a wide range of organisations. Therefore, one aim of Study 2 was to restrict our data to one specific sample. Further, we also assessed level of closeness to the target of bullying as a factor in bystander intervention.

Social psychology has identified ‘we-ness’, or a recognition of common group membership, increases helping behaviours (e.g. Bollmer et al. 2005; Tajfel 1982). Research suggests relationship to target, and in-group membership promotes positive bystander intervention in physical violence (Slater et al. 2013), street violence (Levine et al. 2002), and sexual orientation harassment (Ryan and Wessel 2012). However, while studies identify the role of friendship in adopting certain bystander behaviours and roles in bullying (e.g. Kochenderfer and Ladd 1996; Lodge and Frydenber 2005) this is based on school children and student samples. One exception is D’Cruz and Noronha (2011) study of Indian call-centre agents who witnessed bullying in the workplace. Bystanders responded proactively to the situation as they considered it their personal responsibility to help their friends. In support, Berman et al. (2002) suggest that workplace friendships are beneficial in that they allow individuals to find allies, find support from others at work and support them in turn. Similarly, research on bystander–victim relationships in cybercontexts is also limited. However, studies within a social media context have highlighted positive bystander behaviour towards a target when other bystanders are close friends (Bastiaensens et al. 2014) and when bystanders share similar attitudes (Freis and Gurung 2013). To date, we could not find any published research examining the impact of relationship to target on bystander intervention in workplace cyberbullying.

Theoretically, witness fairness perceptions have been found to be related to perceived identification with a victim (Brockner et al. 1987), and witness deontic injustice perceptions and emotions as well as behaviours towards targets of abusive supervision have been shown to be moderated by target evaluations (Mitchell et al. 2015). Specifically, beliefs that the extent the target deserved the behaviour resulted in co-worker exclusion. With this in mind, we propose bystanders are likely to express an intention to intervene in a bullying context when the victim is a close friend as against an acquaintance because of the social bond they have with the target. It is likely a bystander will experience secondary stress and be more likely to judge the abusive behaviour as unfair. Our next hypotheses are then:

Hypothesis 4a

Bystander intention to intervene will be influenced by whether the victim is a close friend or acquaintance.

Hypothesis 4b

Bystanders’ likelihood of adopting the defender, prosecutor and commuter role will be influenced by whether the victim is a close friend or acquaintance.

The interaction of bullying mode and type with bystanders’ relationship to bullying victims appear to be as yet unexplored in workplace bullying/cyberbullying. In study 1, we suggested that the online nature of cyberbullying may reduce the likelihood of a bystander experiencing social bonds with the victim, potentially moderating their empathic responding. Conversely, if a bystander has previously developed a social bond to the target (as would be expected to a close friend), they are likely to have an empathic understanding with the target and be less prone to the influence of reduced social cues in online communication. Potentially, because of this previous relationship between target and bystander, a deindividuation effect is unlikely to emerge. By contrast if the target is less well known to the bystander, the online nature to cyberbullying could result in the bystander being influenced by reduced social cues, therefore, exhibiting reduced empathic understanding and social identification to the target, resulting in reduced intervention. Our final hypotheses are:

Hypothesis 5a

Bystander intervention intention will be influenced by the interaction between mode and type of bullying and closeness of victim.

Hypothesis 5b

Bystanders’ likelihood of adopting the defender, prosecutor and commuter role will be influenced by the interaction between mode and type of bullying and closeness of victim.

Method

Participants

The study sample size of 468 Australian union members comprised 54.1% female and 45.9% male. Age was categorised showing 20–30 (8.1%), 31–40 (16.2%), 41–50 (27.4%), 51–60 (37.4%) and 61 + (10.9%). Mean tenure was 10.36 years (SD = 9.10), and the sample comprised 16.9% staff, 66.7% supervisors and 16.4% managers.

Measures and Procedure

The same within-participants design (manipulating type and mode of bullying) and dependent variables seen in Study 1 were used again here. A between-participants approach was used to manipulate closeness of target to the respondent. In one version of the scenarios the person depicted was “a friend of yours” and the other version the person was depicted as “a co-worker you do not know really well”. In agreement with a large Australian union, an email link for either the ‘friend’ manipulation or the ‘co-worker’ manipulation was distributed to members of the union. The friend version of the scenario was distributed to members with surnames starting with the letters A to M and the non-friend version to members with surnames starting with N to Z. In total 696 completed responses were obtained; 463 to the friend-based scenarios and 234 to the non-friend scenarios. However, because of the disparity in sample sizes between groups, we randomly chose 234 participants from the friend-based scenarios to use in subsequent analyses.

Results

Descriptive statistics for study variables are presented in Table 2. A 2 × 2 × 2 (type × mode × relationship to target) mixed ANOVA was conducted to examine all effects.

Results indicated a significant main effect of bullying type (F (1, 466) = 76.16, p = 0.001, r = .37) on the extent participants indicated they would respond in some way. Bystanders were significantly more likely to respond when the bullying was personal than work-related (Mdiff = .34, [.28, .41]). There was a small effect of target closeness on bystanders willingness to take some action [F (1, 466) = 3.79, p = 0.052, r = .09], with bystanders more likely to act when the target was a close friend rather than someone they did not know well (Mdiff = .14, [−.00, .28]).

Once again, results indicated a significant main effect of bullying mode [F (1, 466) = 60.12, p < 0.001, r = .34] and type [F (1, 466) = 80.79, p < 0.001, r = .38] on ratings of sympathy with the target. There was a significant (medium-sized) interaction effect between type and mode [F (1, 466) = 36.521, p < 0.001, r = .27]. Bystanders were less likely to adopt the defender role for target’s facing work-related bullying when this behaviour was online (Fig. 2). A small effect of closeness to the target emerged which approached the 5% significance level [F (1, 466) = 3.68, p = 0.056, r = .09]. Bystanders in the ‘close friend’ group were on average higher in support for the target than those in the ‘do not know well’ group (Mdiff = .10 [−01, .20])—although confidence intervals included zero.

In relation to the prosecutor role, a similar pattern to Study 1 emerged. Results indicated significant main effects of mode [F (1, 466) = 81.73, p < 0.001, r = .39] and type [F (1, 466) = 252.50, p < 0.001, r = .59] as well as an interaction effect between mode and type [F (1, 466) = 19.65, p < 0.001, r = .20]. The interaction revealed that the increase in support for the perpetrator’s work-related bullying behaviour is greater when the behaviour is online than offline. Bystanders were more likely to support the perpetrator when the target was not known well to them than when they were a friend (Mdiff = .09, [−.01, .18]), although this was not statistically significant at the 5% level and CIs crossed zero.

A significant large main effect of type was seen for ratings of wavering of support between the perpetrator and target [F (1, 466) = 272.08, p < 0.001, r = .61]. Bystanders were significantly more likely to adopt the commuter role when the bullying was work-related than personal (Mdiff = .60, [.53, .66]). Non-significant effects emerged for mode of bullying, yet in this study, there was a significant (but small effect size) interaction between mode and type [F (1, 466) = 9.55, p = 0.002, r = .14]. The increase in wavering of support between target and perpetrator when witnessing work-related bullying was stronger for offline than online modes (Fig. 3). Target closeness impacted significantly on ratings of wavering [F (1, 466) = 13.26, p = 0.001, r = .17]. While the effect size is small, bystanders were more likely to adopt the commuter role when they did not know the individual well (Mdiff = .24, [.11, .37]).

Overall study 2’s findings highlight further support for hypotheses 1b, 2a, 2b and 3b with some tentative support for hypotheses 4a and 4b (albeit in terms of small effect sizes). No evidence of support for the interaction hypotheses 5a and 5b emerged.

Discussion

This research provides a number of insights in addition to the extant literature in this field. Firstly, it extends the embryonic research on workplace cyberbullying by analysing its influence on behavioural intentions when compared to offline workplace bullying. Secondly, the research progresses from the prevalent dyadic target–perpetrator focus by considering the behavioural intentions of bystanders in relation to different participant roles. This is especially important as bystanders are the largest group affected by workplace bullying (Lutgen-Sandvik 2006) and bystander behaviour has been muted as more complex in cyberbullying (Li et al. 2012). Thirdly, it adopts a robust quasi-experimental approach to examine the impact of mode, type and closeness to target on bystander intentions across two different international samples.

Main effects indicate bystanders were least likely to sympathise with the target and more likely to support the perpetrator when bullying was online and when it was work related. Additionally, a pattern across the two studies suggested an interaction effect between mode and type with bystanders inclined to adopt the prosecutor and less inclined to adopt the defender role for online/work-related bullying behaviours. Effects of target closeness suggested bystanders were more liable to act and have sympathy with the target and less disposed to waver between support for target and perpetrator when the individual was a friend as compared to a co-worker she/he did not know well. However, these effects were small.

Theoretically, results can be interpreted via the combination of justice and stress models. O’Reilly and Aquino (2011) state that when bystanders cognitively judge the severity of harm as high, the perpetrator was to blame and the victim did not deserve it, then the outcome is moral outrage and a desire to restore justice. Similarly, from a stress perspective, bystanders experience stress, develop cognitive and emotional empathy towards the target’s experiences and act to reduce the stress (Robinson et al. 2014). As a result, we would expect to see bystanders expressing a desire to intervene and defend the victim (or retaliate to the perpetrator).

If reduced social cues and behaviour ambiguity in online/work-related bullying creates a deindividuation effect, then this will inhibit empathic understanding towards and social identification with the target of bullying. As a result, a bystander does not place themselves psychologically in the target’s position, rendering them less sensitive to the cognitions and emotions of the target. This failure to experience empathy could cause a bystander to perceive the behaviour as not severe and not violating workplace norms. Consequently, the bystander may not feel moral outrage nor perceive an injustice in the way the victim is being treated—hence, there could be low motivation to intervene. Conversely, offline/personal acts are more severe, blatant and less prone to misinterpretation and as a result seen as contrary to social and organisational norms. Witnessing such behaviours is likely to promote empathy activation and stronger social identity with the target—leading to perceptions of unfairness, deontic anger and more positive bystander intervention.

This thesis could also help explain why bystanders tended to rate specific roles more or less favourably across the different conditions. Work-related negative acts committed online may result in the bystander appraising the acts as not substantially different to what ‘would’ be expected normally; that the perpetrator ‘could’ not have acted differently; and the victim deserved to face the negative act given what ‘should’ happen. To some extent, this is supported by the lower ratings given to the seriousness of the online-work-related bullying scenario. Therefore, relating to Bloch’s (2012) position, bystanders’ moral schema of online/work-related bullying may promote an attribution of the target as deviant, acting contrary to the social norms of the workplace and the cause of his/her problems (prosecutor role). Reduced ratings for the defender role within this context suggest a stronger attribution that the perpetrator’s behaviour is not deviant. Similar to Mitchell et al. in terms of deontic justice, a bystander still believes that what they are doing is ‘right’; it is just that their view of what is right is moderated by mode and type of behaviour.

Injustice perceptions and bystander stress could also explain the findings for closeness to target, as one would expect more empathy, moral outrage and injustice to emerge when witnessing a friend being bullied than an acquaintance. When bystanders have a stronger social identity with the target (as is the case when the target is a close friend), they tended to rate intervention intention and sympathy with the target higher as well as agreement with the perpetrator lower than when the target was not a friend. Yet, no significant interaction effects with mode or type occurred for target closeness to fully support the notion of online behaviour reducing social identity. Perhaps the simulated nature to the research meant participants did not develop a strong social identification with the target, and as a result, empathy levels and moral outrage were not as heightened as would be the case if the victim was actually a close friend. Further research on the relationship between empathy, social identification and mode of bullying needs to try and tease out the dynamics of this process.

Practical Considerations

Organisationally, bystanders are a focal group in interventions to control workplace cyberbullying. They will outnumber targets, perpetrators and supervisors and can be a catalyst for the continuation or reduction of bullying. To reduce ambiguity issues, similar to that advocated for offline bullying (Harvey et al. 2008) as part of any human relations policy development, a clear indication of what constitutes cyberbullying must be detailed. This not only specifies acceptable/unacceptable behaviour online, but should also provide a benchmark for bystanders in justice perceptions. Further, it should be made clear that viewing an abusive message counts as taking part even where a bystander privately disagrees (Macháčková et al. 2013). However, policies are not a cure-all, as traditional workplace bullying literature illustrates there is a lack of trust in policy implementation (Harrington et al. 2012) and limited effectiveness (Beale and Hoel 2011).

Mode of behaviour and type of behaviour appear to reduce positive bystander behaviour possibly via reduced empathy and justice perceptions. Coyne et al. (2017) note: “provision for witnesses to be able to report behaviours and to support a target should be included in order to enhance attention, empathy and social identification” (p. 21). They further suggest a cybermentoring programme could be adopted to assist targets, potentially enhancing the social identification co-workers have with targets. Organisations need to create transparent reporting procedures for bystanders, ensure bystanders feel safe in reporting behaviour and disseminate the procedure to all employees. Advocated by Scully and Rowe (2009), active bystander training encourages positive behaviour and discourages negative behaviour by developing bystander confidence and fostering more active responding. They outline an active bystander tool kit involving practising a number of scenarios in which active approaches to intervention are illustrated. The upshot is that bystanders should learn to develop a more active approach to intervention which fosters social identity with other individuals in the organisation, ultimately embedding a supportive culture throughout the organisation. Linking back to theory, this approach should result in incidences of cyberbullying perceived as unfair and producing bystander stress and, therefore, enhance empathic responding and promote social identity with the victim.

Limitations

As with all quasi-experimental studies, there are a number of limitations to the scope of our research. Firstly, we only focused on email as the form of cyberbullying and did not assess the full range of cyberbullying (e.g. social media, online chat forums). This limits the generalisability of our findings to other acts. School research has indicated email bullying has perceived lower impact than other forms of cyberbullying/bullying (Slonje and Smith 2008). If so, bystanders may not develop empathy or injustice perceptions because of the behaviour being via the perceived low impact mode of email—other forms of cyberbullying may show a different result. We chose to restrict our research to email abuse because of the potential impact on intentions of different forms of cyberbullying acts and the need to control this variable. Further, bullying via email is seen as an increasing problem within the workplace (Shipley and Schwalbe 2007) and the focus of current workplace cyberbullying research (e.g. Ford 2013).

Secondly, to capture the power differential between perpetrator and target inherent within bullying definitions, we specified the perpetrator as the supervisor of both the target and bystander. Supervisors and line managers are often judged the main perpetrators of offline workplace bullying (Hoel et al. 2001; Quine 1999), but this is not universal as peer bullying can be more common than hierarchical bullying (Hogh and Dofradottir 2001). Additionally, Samnani posits that witnesses are more likely to support a perpetrator when the perpetrator is a manager. Social impact theory (Latané 1981) hypothesises that social influence is moderated by source strength, and the stronger the source, the greater the impact on a target’s behaviour. Accordingly, agreement with the perpetrator seen in this study may be due to the perpetrator also being the supervisor of the bystander (high source strength) rather than the influence of mode or type. However, results showing defence of the victim for offline and personal bullying run counter to the notion of source strength as the explanatory factor, suggesting mode and type as more likely explanations.

Thirdly, we advance the notion that mode and type cause reduced empathy and fairness perceptions. Empathy and fairness were not measured directly in the study, particularly bystanders’ trait level of empathy. Dispositional empathy predicts engagement in cyberbullying (Ang and Goh 2010; Kowalski et al. 2014) and adoption of the defender role (Nickerson et al. 2008) in school samples and likelihood of bystander intervention in online abuse in a university sample. Inclusion of trait empathy could moderate the impact of mode and type on bystander intervention intention to the extent that the influence of online bullying should be stronger for individuals lower in trait empathy. Similarly, O’Reilly and Aquino (2011) argue the extent an individual perceives morality as central to his/her self-concept (moral identity), the more likely she/he will act in accordance with moral beliefs and show moral anger to forms of injustice. Therefore, bystander moral identity could influence perceptions of unfairness of negative acts and moderate intervention intention across mode and type of behaviour. Future research should include trait empathy and moral identity in assessing the impact of mode and type on bystander intervention intention.

Fourthly, we did not include variables such as awareness of bullying, tolerance of bullying or country culture in the study which may attenuate bystander intervention intentions. Specifically in relation to culture, research suggests different levels of tolerance of bullying behaviour within countries (Giorgi et al. 2015; Power et al. 2013). Culture (rather than mode or type) could moderate how bystanders perceive the acceptability of behaviours and ultimately their fairness and emotional reaction to them. Therefore, our research is not necessarily generalisable to other cultural contexts.

Finally, albeit the use of experimental vignette methodology (EVM) is an extensive and appropriate method within ethical-decision-making research (Aguinis and Bradley 2014), it is not without its limitations. Specifically, these authors suggest participant level of immersion in the scenario and the conditions participants are responding to the scenarios can impact the external validity of the methodology. The written vignettes used in this study are likely to have has lower fidelity than video/audio presentations and the online presentation affords limited control over the conditions each participant viewed the scenarios (e.g. setting or device used to access). However, Aguinis and Bradley argue that allowing participants to complete scenarios in their natural setting does enhance the realism of EVM.

In conclusion, extending the embryonic research into workplace cyberbullying, the two related quasi-experimental studies reported here highlight a consistent interaction effect of mode (online/offline) and type (work-related/personal) on the extent bystanders adopt defender or prosecutor roles. Bystanders are more open to adopting the prosecutor role in online/work-related acts and the defender role in offline/personal acts. Practical intervention needs to therefore focus on establishing mechanisms where bystanders feel safe in intervening positively to enhance empathic understanding and injustice perceptions of victim experiences.

References

Aguinis, H., & Bradley, K. J. (2014). Best practice recommendations for designing and implementing experimental vignette methodology studies. Organizational Research Methods, 17(4), 351–371.

Alexander, C., & Becker, H. (1978). The use of vignettes in survey research. Public Opinion Quarterly, 42, 93–104.

Ang, R. P., & Goh, D. H. (2010). Cyberbullying among adolescents: The role of affective and cognitive empathy, and gender. Child Psychiatry Human Development, 41, 387–397.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Barlińska, J., Szuster, A., & Winiewski, M. (2013). Cyberbullying among adolescent bystanders: Role of the communication medium, form of violence, and empathy. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 23, 37–51.

Baruch, Y. (2005). Bullying on the net: Adverse behavior on e-mail and its impact. Information & Management, 42(2), 361–371.

Bastiaensens, S., Vandebosch, H., Poels, K., Van Cleemput, K., DeSmet, A., & De Bourdeaudhuij, I. (2014). Cyberbullying on social network sites. An experimental study into bystanders’ behavioural intentions to help the victim or reinforce the bully. Computers in Human Behaviour, 31, 259–271.

Bauman, S., & Del Rio, A. (2006). Preservice teachers’ responses to bullying scenarios: Comparing physical, verbal and relational bullying. Journal of Education Psychology, 98(1), 219–231.

Beale, D., & Hoel, H. (2011). Workplace bullying and the employment relationship: Exploring questions of prevention, control and context. Work, Employment & Society, 25(1), 5–18.

Berman, E. M., West, J. P., & Richter, M. N., Jr. (2002). Workplace relations: Friendship patterns and consequences (according to managers). Public Administration Review, 62(2), 217–230.

Bloch, C. (2012). How witnesses contribute to bullying in the workplace. In N. Tehrani (Ed.), Workplace Bullying (pp. 81–96). East Sussex: Routledge.

Bollmer, J. M., Milich, R., Harris, M. J., & Maras, M. A. (2005). A friend in need: The role of friendship quality as a protective factor in peer victimization and bullying. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(6), 701–712.

Brockner, J., Grover, S., Reed, T., DeWitt, R., & O’Malley, M. (1987). Survivors’ reactions to layoffs: we get by with a little help for our friends. Administrative Science Quarterly, 32(4), 526–541.

Byron, K. (2008). Carrying too heavy a load? The communication and miscommunication of emotion by email. Academy of Management Review, 33(2), 309–327.

Campbell, M. A. (2005). Cyber bullying: An old problem in a new guise? Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 15(1), 68–76.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Coyne, I. (2011). Bullying in the workplace. In C. P. Monks & I. Coyne (Eds.), Bullying in different contexts (pp. 157–184). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Coyne, I., Farley, S., Axtell, C., Sprigg, C., Best, L., & Kwok, O. (2017). Workplace cyberbullying, employee mental strain and job satisfaction: A dysempowerment perspective. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(7), 945–972.

D’Cruz, P., & Noronha, E. (2011). The limits to workplace friendship: Managerialist HRM and bystander behaviour in the context of workplace bullying. Employee Relations, 33(3), 269–288.

Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., & Notelaers, G. (2009). Measuring exposure to bullying and harassment at work: Validity, factor structure and psychometric properties of the negative acts questionnaire-revised. Work & Stress, 23(1), 24–44.

Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., & Cooper, C. L. (2003). Bullying and emotional abuse in the workplace: International perspectives in research and practice. London: CRC Press.

Escartín, J., Rodríguez-Carballeira, A., Zapf, D., Porrúa, C., & Martin-Pena, J. (2009). Perceived severity of various bullying behaviours at work and the relevance of exposure to bullying. Work & Stress, 23(3), 191–205.

Escartín, J., Ullrich, J., Zapf, D., Schlüter, E., & van Dick, R. (2013). Individual-and group-level effects of social identification on workplace bullying. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22(2), 182–193.

Farley, S., Coyne, I., Axtell, C., & Sprigg, C. (2016). Design, development and validation of a workplace cyberbullying measure (WCM). Work & Stress, 30(4), 293–317.

Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2004). Third-party punishment and social norms. Evolution and Human Behavior, 25, 63–87.

Folger, R., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2005). Beyond counterproductive work behaviour: Moral emotions and deontic retaliation versus reconciliation. In S. Fox & P. E. Spector (Eds.), Counterproductive work behavior: Investigations of actors and targets (pp. 83–105). Washington: American Psychological Association.

Ford, D. P. (2013). Virtual harassment: Media characteristics’ role in psychological health. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 28(4), 408–428.

Fox, S., & Cowan, R. L. (2014). Revision of the workplace bullying checklist: The importance of human resource management’s role in defining and addressing workplace bullying. Human Resource Management Journal, 25(1), 116–130.

Freis, S. D., & Gurung, R. A. R. (2013). A facebook analysis of helping behavior in online bullying. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 2(1), 11–19.

Giorgi, G., Leon-Perez, J., & Arenas, A. (2015). Are bullying behaviors tolerated in some cultures? Evidence for a curvilinear relationship between workplace bullying and job satisfaction among Italian workers. Journal of Business Ethics, 131, 227–237.

Giumetti, G. W., Hatfield, A. L., Scisco, J. L., Schroeder, A. N., Muth, E. R., & Kowalski, R. M. (2013). What a rude e-mail! Examining the differential effects of incivility versus support on mood, energy, engagement, and performance in an online context. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(3), 297–309.

Giumetti, G. W., McKibben, E. S., Hatfield, A. L., Schroeder, A. N., & Kowalski, R. M. (2012). Cyber incivility @ work: The new age of interpersonal deviance. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15(3), 148–154.

Glomb, T. M., Richman, W. L., Hulin, C. L., Drasgow, F., Schneider, K. T., & Fitzgerald, L. F. (1997). Ambient sexual harassment: An integrated model of antecedents and consequences. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 71(3), 309–328.

Harrington, S., Rayner, C., & Warren, S. (2012). Too hot to handle? Trust and human resource practitioners’ implementation of anti-bullying policy. Human Resource Management Journal, 22(4), 392–408.

Harvey, M., Treadway, D., Heames, J. T., & Duke, A. (2008). Bullying in the 21st century global organization: An ethical perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 85, 27–40.

Hershcovis, M. S. (2011). “Incivility, social undermining, bullying… oh my!”: A call to reconcile constructs within workplace aggression research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(3), 499–519.

Hoel, H., Cooper, C. L., & Faragher, B. (2001). The experience of bullying in Great Britain: The impact of organizational status. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 10(4), 443–465.

Hoel, H., Cooper, C. L., & Faragher, B. (2004). Bullying is detrimental to health, but all bullying behaviours are not necessarily equally damaging. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 32, 367–387.

Hogh, A., & Dofradottir, A. (2001). Coping with bullying in the workplace. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 10(4), 485–496.

Jennifer, D., Cowie, H., & Ananiadou, K. (2003). Perceptions and experience of workplace bullying in five different working populations. Aggressive Behaviour, 29, 489–496.

Kochenderfer, B. J., & Ladd, G. W. (1996). Peer victimization: Manifestations and relations to school adjustment in kindergarten. Journal of School Psychology, 34, 267–283.

Kowalski, R. M., Giumetti, G. W., Schroeder, A. N., & Lattanner, M. R. (2014). Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 1073–1137.

Kowalski, R. M., Limber, S. P., & Agatston, P. W. (2012). Cyberbullying: Bullying in the digital age (2nd ed.). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Latané, B. (1981). The psychology of social impact. American Psychologist, 36, 343–356.

Levine, M., Cassidy, C., Brazier, G., & Reicher, S. (2002). Self-categorization and bystander non-intervention: Two experimental studies. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(7), 1452–1463.

Leymann, H. (1990). Mobbing and psychological terror at workplaces. Violence and Victims, 5(2), 119–126.

Li, Q., Smith, P. K., & Cross, D. (2012). Research into cyberbullying. In Q. Li, D. Cross, & P. K. Smith (Eds.), Cyberbullying in the global playground (pp. 3–12). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Lodge, J., & Frydenber, E. (2005). The role of peer bystanders in school bullying: Positive steps toward promoting peaceful schools. Theory into Practice, 44, 329–336.

Lutgen-Sandvik, P. (2006). Take this job and…: Quitting and other forms of resistance to workplace bullying. Communication Monographs, 73(4), 406–433.

Macháčková, H., Dedkova, L., Sevcikova, A., & Cerna, A. (2013). Bystanders’ support of cyberbullied schoolmates. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 23, 25–36.

Mitchell, M. S., Vogel, R. M., & Folger, R. (2015). Third parties’ reactions to the abusive supervision of coworkers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(4), 1040–1055.

Moreno-Jiménez, B., Rodríguez-Muñoz, A., Pastor, J. C., Sanz-Vergel, A. I., & Garrosa, E. (2009). The moderating effects of psychological detachment and thoughts of revenge in workplace bullying. Personality and Individual Differences, 46, 359–364.

Namie, G., & Lutgen-Sandvik, P. (2010). Active and passive accomplices: The communal character of workplace bullying. International Journal of Communication, 4, 343–373.

Nickerson, A. B., Mele, D., & Princiotta, D. (2008). Attachment and empathy as predictors of roles as defenders or outsiders in bullying interactions. Journal of School Psychology, 46, 687–703.

Nielsen, M. B., Matthiesen, S. B., & Einarsen, S. (2010). The impact of methodological moderators on prevalence rates of workplace bullying: A meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83, 955–979.

O’Reilly, J., & Aquino, K. (2011). A model of third parties’ morally motivated responses to mistreatment in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 36(3), 526–543.

Parzefall, M. R., & Salin, D. M. (2010). Perceptions of and reactions to workplace bullying: A social exchange perspective. Human Relations, 63(6), 761–780.

Patient, D. L., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2010). Increasing interpersonal and informational justice when communicating negative news: The role of the manager’s empathic concern and moral development. Journal of Management, 36(2), 555–578.

Paull, M., Omari, M., & Standen, P. (2012). When is a bystander not a bystander? A typology of the roles of bystanders in workplace bullying. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 50, 351–366.

Porath, C. L., & Erez, A. (2009). Overlooked but not untouched: How rudeness reduces onlookers’ performance on routine and creative tasks. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 109, 29–44.

Power, J. L., Brotheridge, C. M., Blenkinsopp, J., Bowes-Sperry, L., Bozionelos, N., Buzády, Z., et al. (2013). Acceptability of workplace bullying: A comparative study on six continents. Journal of Business Research, 66(3), 374–380.

Privitera, C., & Campbell, M. A. (2009). Cyber-bullying: The new face of workplace bullying? Cyber Psychology & Behavior, 12, 395–400.

Quine, L. (1999). Workplace bullying in NHS community trust: Staff questionnaire survey. British Medical Journal, 318, 228–232.

Reich, T. C., & Hershcovis, M. S. (2015). Observing workplace incivility. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(1), 203–215.

Robinson, S. L., Wang, W., & Kiewitz, C. (2014). Coworkers Behaving Badly: The impact of coworker deviant behavior upon individual employees. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 123–143.

Ryan, A. M., & Wessel, J. L. (2012). Sexual orientation harassment in the workplace: When do observers intervene? Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 33(4), 488–509.

Samnani, Al-K. (2013). “Is this bullying?” Understanding target and witness reactions. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 28(3), 290–305.

Scully, M., & Rowe, M. (2009). Bystander training within organizations. Journal of the International Ombudsman Association, 2(1), 1–9.

Shipley, D., & Schwalbe, W. (2007). Send: The essential guide to email for office and home. Knopf, NY: Alfred A.

Siegel, J., Dubrovsky, V., Kiesler, S., & McGuire, T. (1986). Group processes in computer-mediated communication. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 37, 157–187.

Simpson, R., & Cohen, C. (2004). Dangerous work: The gendered nature of bullying in the context of higher education. Gender, Work and Organization, 11(2), 163–186.

Skarlicki, D. P., & Rupp, D. E. (2010). Dual processing and organizational justice: The role of rational versus experiential processing in third-party reactions to workplace mistreatment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 944–952.

Slater, M., Rovira, A., Southern, R., Swapp, D., Zhang, J. J., Campbell, C., et al. (2013). Bystander responses to a violent incident in an immersive virtual environment. PLoS ONE, 8(1), 1–13.

Slonje, R., & Smith, P. K. (2008). Cyberbullying: Another main type of bullying? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 49, 147–154.

Spears, B., Slee, P., Owens, L., & Johnson, B. (2009). Behind the scenes and screens: Insights into the human dimension of covert and cyberbullying. Zeitschrift fur Psychologie/Journal of Psychology, 217(4), 189–196.

Suler, J. (2004). The online disinhibition effect. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 7(3), 321–326.

Tajfel, H. (1982). Social psychology of intergroup relations. Annual Review of Psychology, 33, 1–39.

Van Heugten, K. (2011). Theorizing active bystanders as change agents in workplace bullying of social workers. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 92(2), 219–224.

Vartia, M. (2001). Consequences of workplace bullying with respect to the well-being of its targets and the observers of bullying. Scandinavian Journal of Work Environment Health, 27(1), 63–69.

Vranjes, I., Baillien, E., Vandebosch, H., Erreygers, S., & De Witte, H. (2017). The dark side of working online: Towards a definition and an emotion reaction model of workplace cyberbullying. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 324–334.

Weatherbee, T. G., & Kelloway, E. K. (2006). A case of cyberdeviancy: CyberAggression in the workplace. In E. K. Kelloway, J. Barling, & J. J. Hurrell (Eds.), Handbook of workplace violence (pp. 445–487). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.

Wilks, T. (2004). The use of vignettes in qualitative research into social work values. Qualitative Social Work, 3(1), 78–87.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Work-Related Offline Scenario

Your colleague, who joined your unit 6 months ago, has been called into the supervisor’s office again. Through the open door, everyone in your unit can hear the supervisor loudly criticising your co-worker for not submitting a technical, lengthy report, which had only been assigned to them the previous day. You can see that your co-worker’s in-tray is overflowing with other projects, and you hear your colleague raise the issue of the tight deadlines. The supervisor responds that all work in the department is “urgent” and that the employee should practise better time management. It is not the first time you have overheard this type of conversation between the supervisor and this particular colleague—since they started on the job they regularly get “summoned” in by the supervisor for these discussions about “late” submissions.

Work-Related Online Scenario

You have been assigned to a project with your co-worker, who has forwarded you a document from your supervisor in an email outlining the project details. However, your colleague has not cleared the previous email correspondence, and you inadvertently notice in the email history that this person has been getting extra emails from the supervisor in addition to the weekly work allocation email. The emails from the supervisor to your co-worker include many requests for follow-up reports on assignments and status updates, sometimes the day after the assignment was given. There is only one outgoing email from your co-worker that you can see, saying that they are having a hard time meeting the short deadlines and asking for more time to complete assignments. The supervisor’s email reply tells them “The work in this department is URGENT and it’s about time you started practising better time management skills”. It then outlines a list of outstanding tasks under the heading “LATE”. As you scroll through the email history, you notice many other similar demands and criticisms.

Personal Offline Scenario

Since the new assistant joined your office about 6 months ago, the department supervisor has been going round the office openly criticising how they work. You have also heard the supervisor questioning how the assistant got the job in the first place. This has led to the circulation of rumours in your department. These rumours have gotten back to the assistant, who is also not invited to any of the after-work socialising events. Your supervisor has continued to criticise the assistant’s pace and style of work and has even recently assigned them a nickname that reflects this.

Personal Online Scenario

You received an email about an after-work social event from your supervisor. You have noticed that since the new assistant joined 6 months ago, they have never been included in any of these e-invites. You and your colleagues in your unit have regularly been forwarded emails from the Supervisor with criticisms of how the assistant does their work and their pace of completing tasks, as well as messages such as “How in the world did this person manage to get this job????” This sparked a long email chain of responses including rumours about the assistant and actually led to the creation of a nickname based on the descriptions of them in the emails.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Coyne, I., Gopaul, AM., Campbell, M. et al. Bystander Responses to Bullying at Work: The Role of Mode, Type and Relationship to Target. J Bus Ethics 157, 813–827 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3692-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3692-2