Abstract

The corporate citizenship (CC) concept introduced by Dirk Matten and Andrew Crane has been well received. To this date, however, empirical studies based on this concept are lacking. In this article, we flesh out and operationalize the CC concept and develop an assessment tool for CC. Our tool focuses on the organizational level and assesses the embeddedness of CC in organizational structures and procedures. To illustrate the applicability of the tool, we assess five Swiss companies (ABB, Credit Suisse, Nestlé, Novartis, and UBS). These five companies are participants of the UN Global Compact (UNGC), currently the largest collaborative strategic policy initiative for business in the world (www.unglobalcompact.org). This study makes four main contributions: (1) it enriches and operationalizes Matten and Crane’s CC definition to build a concept of CC that can be operationalized, (2) it develops an analytical tool to assess the organizational embeddedness of CC, (3) it generates empirical insights into how five multinational corporations have approached CC, and (4) it presents assessment results that provide indications how global governance initiatives like the UNGC can support the implementation of CC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Today many multinational companies publicly commit to corporate social responsibility (CSR).Footnote 1 The CSR concept, however, is operationally vague in content and macro-level in orientation (Garriga and Mele 2004; Windsor 2006). A clearer defined subset of CSR, corporate citizenship (CC), specifically captures the new political role of corporations in globalization. Matten et al. (2003) developed a specific perspective of CC, based on the observation that global governance—referring to rule-making and rule-implementation on a global scale—is no longer a task managed by the state alone (Braithwaite and Drahos 2000; Kaul et al. 1999, 2003; Zürn 2002). Instead, Multinational Corporations (MNCs) as well as civil society groups contribute to the formulation and implementation of rules in public policy areas that were once largely the responsibility of the state (Scherer et al. 2006). Matten and Crane (2005), therefore, develop an “extended” concept of CC and suggest that “corporate citizenship” describes “the role of the corporation in administering citizenship rights,” with corporations providing social rights, enabling civil rights and channeling political rights (Matten and Crane 2005, p. 172 et seq.). CC so defined is narrower and clearer than CSR.

As the idea of integrating companies into the solution of global public goods, problems has become increasingly popular (Kaul et al. 1999, 2003), the question is no longer why companies should engage in CC, but how they effectively do so. The increasing popularity of the CC concept raises the issue of what CC actually entails. CC definitions in academia and practice vary (Crane et al. 2008; Logsdon and Wood 2002; Matten and Crane 2005; Waddock 2008). They stretch from philanthropic approachesFootnote 2 to the “business case,”Footnote 3 and do not provide a coherent orientation for the implementation process in management practice. As a result, it has become necessary to look behind the façade of what corporations call CC. The analysis of whether corporations created the organizational preconditions for filling regulatory gaps in situations where governments are unable or unwilling to provide public goods or guarantee basic rights (Scherer et al. 2006, 2009) requires the development of an assessment tool capable of analyzing corporate structures and procedures. The tool must be able to capture different degrees of the organizational “embeddedness” of CC and reveal whether organizational structures and procedures are indeed designed in ways that enable a company to systematically realize CC.

The relevance of assessing the alignment of internal structures and procedures with CC claims has been highlighted by the case of BP. BP has been an active member of multiple social and environmental initiatives (including the UN Global Compact; UNGC) and its public image has been created around the “Beyond Petroleum” strategy. Yet, the oil spill crisis in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010 revealed BP’s history of safety violations in its core business. Investigations made clear that rigorously implemented safety procedures could have sent early warning signals and possibly prevented the ecological disaster. The lack of standard operating safety procedures stand in stark contrast to the company’s claims to be an impeccable responsible company and shows the insufficient organizational embeddedness of CC.Footnote 4 Against this background, the purpose of our research project is, on the one hand, to clarify what CC stands for, and, on the other hand, to develop an assessment tool to analyze how companies implement CC.

The research project contributes to the literature in four ways. First, it further develops Matten and Crane’s CC definition and builds a concept of CC that can be operationalized. Second, it theoretically develops an analytical tool to assess the embeddedness of CC in organizational structures and procedures. Third, empirical data on the organizational “embeddedness” of CC will be collected from five large corporations with headquarters in Switzerland, to illustrate the usefulness of the tool. Finally, the article highlights the need to specify the understanding of the role of the corporation in global governance and change perspective from CSR to CC. These insights provide indications how global governance initiatives like the UNGC can create incentives for corporations to transform their CSR engagement into CC. The project closes research gaps, first, by developing an assessment tool for CC. The tool focusses on the organizational level and thus represents a useful corrective to the predominantly macro-level orientation of CSR and CC research. Existing tools are neither linked to CC theory nor are they methodologically sound (see below). Second, empirical data on the organizational “embeddedness” of CC will be collected to establish baseline data on the implementation process. Given the sharp criticism of companies that sign up for CSR or CC initiatives for formal adherence only (and the lack of monitoring and enforcement mechanisms of these initiatives, e.g., the UNGC), such empirical data are timely and comparable studies have not yet been conducted. Our study may, therefore, deliver a conceptual framework for future comparative studies on the implementation process in various countries, or on companies with various characteristics, such as size and industry (Baumann-Pauly et al. 2011).

The rest of this article is divided into four main parts. In the first part, we will develop a concept of CC based on Matten and Crane’s definition of CC. Matten and Crane (2005) describe a distinct role for business in emerging global governance structures (Matten and Crane 2005). In the second part, we outline our research design and introduce a tool to assess the “embeddedness of CC” in corporate structures and procedures. The degree of “embeddedness” is considered as the main indicator for assessing whether corporations are prepared to realize CC systematically through daily business routines. The tool will be derived from an organizational learning model drafted by Zadek (2004). The model identifies five typical stages of the development of companies that engage in CC, with the final stage, the “civil stage,” covering CC as conceptualized in the first part. In the third part, the results of the empirical analysis of five Swiss UN Global Compact (UNGC) business participants are sketched out to illustrate the validity of the tool. The results show that although all five companies joined the UNGC at the same time, they are at different stages in the development process. Implications and limitations of the research are summarized in the “Conclusion.”

Corporations as Corporate Citizens: Developing a Concept of CC

Matten and Crane (2005, p. 173) define CC as “the role of the corporation in administering citizenship rights for individuals.” This definition lays the foundation for our study yet we will highlight in the following which aspects need to be further developed to build a CC concept that can be operationalized and examined empirically.

Prescriptions on How to Resolve Legitimacy Challenges

Matten and Crane’s (2005) definition of CC does not provide guidance on how to solve the legitimacy question that arises when corporations are conceptualized as political actors with a public role. Matten and Crane (2005) themselves are aware of this issue and they are rather pessimistic with regard to the legitimacy challenges. Corporations and their managers are not elected or controlled like democratic governments. Therefore, the theory needs to be developed further with the aim of assessing and justifying CC measures and policies where their legitimacy is called into question (see Palazzo and Scherer 2006; Zürn 2000, p. 190).

To address the legitimacy issues of the CC concept, Palazzo and Scherer (2006) propose a “communicative framework” to legitimize the rule-making activities of private actors in global governance processes.Footnote 5 They build on Suchman’s (1995) typology of organizational legitimacy, which differentiates among pragmatic (social acceptance based on perceived benefits), cognitive (social acceptance based on unconscious taken-for-grantedness), and moral legitimacy (social acceptance based on explicit moral discourse). To achieve organizational legitimacy, corporations have to “pursue socially acceptable goals in a socially acceptable manner” (Ashforth and Gibbs 1990, p. 177). Palazzo and Scherer (2006) argue that, given the conditions of globalization, neither pragmatic nor cognitive legitimacy is sufficiently manageable. “Therefore, moral legitimacy has become the core source of societal acceptance.” (Palazzo and Scherer 2006, p. 78).

Moral legitimacy refers to a conscious moral judgment on the corporation’s products, organizational structures, processes, and leaders. It is based on an “explicit public discussion” which creates the opportunity for corporations to justify and explain their decisions. At the same time, it obliges corporations to participate in the discussions and consider alternative arguments (see Suchman 1995, p. 585). The challenge, therefore, is to convince rather than manipulate opponents (Ashforth and Gibbs 1990; Palazzo and Scherer 2006).

Since the “legitimacy” of a corporation is regarded as a critical resource for a company’s “licence to operate”, many corporations nowadays regularly meet with their stakeholders to discuss critical issues and future business strategy (see, e.g., Lafarge 2009). Corporations are resource-dependent, and to operate in a way that is perceived as legitimate in an increasingly heterogeneous environment is vital for the corporation’s survival. Integrating elements that increase accountability and reconcile the multiplicity of contradictory moral and legal requirements of a global society (e.g., through dialogue, transparency, participation, etc.) thus represents a serious challenge for management (Palazzo and Scherer 2006). To manage corporate legitimacy, corporations must, therefore, integrate interactive elements in their implementation strategy of CC.

Limits and Scope of Corporate Responsibility

Matten and Crane’s definition of CC does not spell out any limits of corporate responsibility (on such limits see Santoro 2000; Steinmann 2007). In its current form, companies would be responsible to provide citizenship rights everywhere and for everybody. Yet, for corporations whose primary role is an economic one such a general and holistic responsibility is not feasible. The scope of the responsibility of corporations is still at issue (e.g., see the debate on the “sphere of influence” in the context of the UNGC, or recently developed Guiding Principles of Business and Human RightsFootnote 6). Instead of waiting for a conclusion of these debates, we suggest introducing a process perspective to defining the limits of corporate responsibility.Footnote 7 We argue that, in principle, the focus of corporate responsibility must be on corporate activities that are directly linked to the company’s core business and value creation (Steinmann 2007). To ensure that CC is realized through core business operations, organizational structures and procedures need to be aligned with the commitment to CC (e.g., hiring, promotion, and bonus policies; training, complaints, or impact assessment procedures) (Paine 1994; Stansbury and Barry 2007). However, the structures and the procedures have to be supplemented by integrated interactive mechanisms for stakeholder engagement (see above). If stakeholders get the chance to provide feedback on the organizational set-up and the company’s position, the limits of responsibility are being subjected to a regular review that takes into account situational factors such as the urgency of the issue, the resources required, or the corporate capacities.

Guidelines on How to Realize CC

The extended concept of CC proposed by Matten and Crane (2005) is purely descriptive and does not outline practical guidelines on what corporations could do to realize CC in their organization. The authors make clear that they do not advocate that corporations should engage in CC and consequently they also do not provide specific strategies or procedures on how to implement CC. Self-regulation, however, has already become a common corporate practice and initiatives like the UNGC create further incentives for such political activities of corporations (Detomasi 2007).

Nevertheless, it is still not clear how organizational structures and procedures should be designed to make CC a reality. Empirical studies on the implementation of CC are scarce and a systematic review of “good practice” examples does not yet exist. Since such practical guidelines are missing, most corporations are still experimenting with the design of organizational structures and procedures that are supposed to promote CC in daily operations. For example, some corporations have set up designated CC departments, while others believe that in principle all line managers should be in charge of CC. Likewise, it is unclear how to design incentive structures, training manuals, and impact studies. Thus, many aspects regarding the technical implementation of CC have yet to be analyzed and developed. Nevertheless, it is unlikely that a blueprint for the CC implementation will ever emerge. Given the uniqueness of each company, this is probably also undesirable. Yet, all companies that practice CC have at least one thing in common: They in principle commit to assuming a political role in addition to their economic role by systematically contributing to public goods. In order to figure out how to operate according to this commitment through the conduct of business requires taking risks, a willingness to experiment and the openness to learn from experience. So, what stands at the beginning of all corporate citizens is the commitment to start the CC journey, and a visionary leadership that endorses the process.

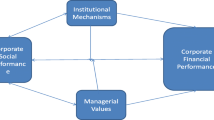

In conclusion, we elaborated on the three aspects that need to be further developed in the definition of Matten and Crane to build a CC concept that is operational. Based on our discussion above, we argue that corporations that strive to become corporate citizens first and foremost need to address the legitimacy challenges of its new political role by integrating stakeholder feedback in their business decisions and by supporting collaborative initiatives to CC (interactive dimension of CC). Aspiring corporate citizens must also define organizational rules and procedures that guide their daily business operations. These organizational rules and procedures define the general scope of the company’s engagement in political issues yet if the stakeholder context requires more or less engagement, adjustments are negotiable (structures and procedural dimension of CC). Corporate citizens also need a leadership team that fully commits to CC and that supports exploring various approaches to the CC implementation (commitment dimension of CC). Hence, we are defining the following three organizational dimensions for CC: commitment measures (1), structural and procedural measures (2), and interactive measures (3).

-

(1)

Corporate citizens ensure that their commitment is firmly embedded on a commitment level. Implementing CC on a commitment level ensures that the corporation demonstrates it is willing to systematically fill regulatory gaps through their global business activities in line with international regulations or universally accepted rules such as human rights. Commitment measures are particularly crucial in cases, in which states are unable or unwilling to provide basic rights to their citizens (Hsieh 2009). Consequently, an explicit commitment to CC is required by the leadership of the corporation and, as a result, CC should feature in strategic documents and in basic policies, for example, the company’s mission statement or the Code of Conduct. The commitment, however, should not only be visible in official statements but also be integrated in the culture of the organization and the ethos of the firm representatives. Therefore, the commitment level of CC covers both formal and informal elements.

-

(2)

CC must be embedded on a structural and procedural level to ensure that the commitments are realized. The structural and procedural dimensions describe the internal “embeddedness” of CC in daily operations which includes the alignment of specific policies, for example, in the area of human resources (recruitment, promotions, bonuses, training), the creation of complaints procedures, reporting and evaluation mechanisms. Its characteristics range from a command and control type of implementation to a more participatory implementation of CC. Integrating systematic compliance checks in all core business activities, yet allowing for discursive ethical reflections in dilemma situations as prescribed by insights gained from the comparison of compliance and the integrity approach (see Paine 1994) makes it possible to define the limits of CC adequately to context and situation.

-

(3)

An interactive aspect in the implementation process is indispensable for advancing CC and defining its limits. The interactive dimension describes the relationships of the corporation with external stakeholders. It ranges from monologue to dialogue. In order to communicatively construct organizational legitimacy, solid stakeholder relationships are based upon regular dialogue (Suchman 1995). Interacting with stakeholders helps the corporation, on the one hand, to develop antennas for societal trends and concerns and to potentially anticipate crisis cases. On the other hand, regular interaction allows corporations to react swiftly to emerging crises, namely, according to the level of urgency and consistency of societal issues (Scherer et al. 2008).

Designing Research on CC: The Development of an Assessment Tool

In this section, we first describe the design of our empirical research of CC at five Swiss MNCs and then we elaborate on the development of the assessment tool.

Research Design: Assessment Method, Case Selection, and Interview Process

A research project among UNGC participants in Switzerland conducted in 2003 demonstrated that surveys do not sufficiently serve to reveal the actual state of implementation of CC (Zillich 2003). The results of this survey suggest that the implementation of CC is already very advanced (Zillich 2003). In their self-assessment reports, the participating companies claimed to fully apply developed management policies during the implementation process. Yet, interview-based data, as collected after the aforementioned survey, do not correspond with these findings. These contradictory research results can probably be explained by the popularity of the UNGC, for which surveys are routinely filled out. Surveys lend themselves to making “politically desirable” statements about the state of implementation and they often do not reveal information mirroring the actual state of development (see Fernandez and Randall 1992; Randall and Fernandes 1991). For example, in the 2003 survey, companies were asked whether and how they communicate the mission of the UNGC to employees and how they ensure compliance. All companies replied that they inform employees about the UNGC. Some said that they conduct training courses on CC, and some even claimed to have introduced an incentive system to motivate employees to apply the UNGC principles (see Zillich 2003, p. 22). In-depth interviews performed after the survey among company representatives, however, revealed that, while all companies inform employees about the UNGC at some point (e.g., in a brochure for all new employees), training courses which simulate ethical decision-making situations have yet to be developed. The alignment of incentive structures is also a work-in-progress with very limited impact on promotions and bonus payments to date (see below). This experience highlights the validity issues linked with CSR surveys.

Fernandez and Randall’s (1992) analysis of the methods in ethics research provides insights that could explain the discrepancy of findings between the 2003 survey and our 2007 assessment. Fernandez and Randall (1992) analyzed the social desirability response effects in survey-based ethics research. They conclude that, in the study of business ethics, there is a tendency for respondents to deny socially undesirable traits or behavior and to admit to socially responsible ones (Fernandez and Randall 1992). For this reason, quantitative researchers should be very careful when developing analysis instruments and interpreting results to diminish this social desirability effect. Qualitative interviews create the opportunity to account for the bias directly and to rectify it during the course of the data collection. Qualitative interview studies, however, create their own problems of subjective bias. Given these experiences with ethics research, we decided conducting qualitative interviews to be able to directly control for a potential bias.

In addition, CC and its organizational implementation represent an empirically unexplored field. The CC concept is highly abstract and the definition of several aspects of CC is still ambiguous. A qualitative approach helps to better understand the characteristics of CC in practice. It serves to fine-tune the definition of CC and to develop the concept further into a valuable theory. There is also some precedence for this kind of conceptual approach in the literature. For example, the study of ethical leadership at first chose an interview-based approach over quantitative methods to further sharpen the concept and to develop theory (Brown et al. 2005). The assessment of CC “embeddedness” in organizational structures and procedures thus follows a similar research pattern to advance CC in theory and practice.

Last but not least, company surveys represent a limited method to assess the implementation of CC as they neglect the reactions of the various stakeholders to whom companies are ultimately accountable. These surveys often rely on a single data source, namely, the self-assessment of responsible managers, or, even worse, the assigned members of the corporate communication departments who are normally rather detached from the various value change activities in which problematic CC issues may occur. As we will see from the definition of CC below, the viewpoints of the various constituencies within the company must be included in order for CC implementation measurements to be valid. Thus, a method integrating the voices of various stakeholders draws a more accurate picture of the “CC embeddedness.” Stakeholder opinions about the corporate implementation of CC are, therefore, integrated in the interactive dimension of CC in the assessment tool.

For the reasons outlined above, we decided against surveying a large number of companies and instead conduct in-depth case studies of a few companies that are likely to represent data-rich cases for CC. We decided to analyze the CC approach of companies that are participating in the UNGC because the idea behind this initiative, namely, to encourage corporations to systematically contribute to the solution of global governance issues, largely corresponds with our understanding of CC. By selecting companies that participate in the UNGC does not mean that we idealize the initiative; in fact, we share the questions that many critical authors raise about the initiative’s actual implementation status and hence find it interesting to look behind the façade of businesses that decorate themselves with the UN flag (Banerjee 2007; Deva 2006; Laufer 2003, 2006; Nolan 2005; Sethi 2003).

To increase the likelihood of analyzing data-rich cases, Switzerland was chosen as the context for the study. From a theoretical perspective, Switzerland presents an interesting environment for studying the implementation of the UNGC because the Swiss government as well as a number of Swiss multinationals were among the main supporters of the UNGC. Given this level of support, Swiss participants are possibly particularly advanced in implementing the UNGC’s objectives and the analysis of Swiss participants of the initiative might reveal “good practice” models for CC implementation. Thus, the cases were chosen because it is believed that understanding them will lead to better comprehension and perhaps to theorizing about a still larger collection of cases (for support on this methodological argument see Silverman 2005, p. 126; Stake 2005, p. 446). In addition, the focus on companies with their home base only in one legislative, political, and social context excludes the potential national influence on the commitment of companies to CC.

All selected companies joined the UNGC in its first year, between 2000 and 2001. The reason for choosing only companies that joined the UNGC immediately after its inception was to allow the maximum time period for embedding CC in organizational structures and procedures as it is assumed that a thorough integration process is time-consuming. It is also assumed that analyzing organizational structures and procedures at MNCs is easier than at SMEs due to their higher degree of formalized processes (Murillo and Lozano 2006; Spence 2007). Therefore, SMEs were not included in this study.Footnote 8 Based on these selection criteria, we analyzed five Swiss MNCs, all among the first signatories of the UNGC: ABB, Credit Suisse, Nestlé, Novartis, and UBS.

A thorough document analysis via the respective corporate websites and CSR reports as well as the websites of watchdog organizations served to prepare for the interviews. This analysis provided first indications for the critical issues of each company, the corporate positioning and the quality of relationship between the corporation and its critics. In order not to prime the interviewees for “CC” as a controversially defined concept and to avoid terminological confusion, neither CC nor “Corporate Social Responsibility” (CSR), or any other terms describing the company’s commitment to the UNGC, were used during the interviews. Instead, corporate representatives (often from PR or CSR departments) were asked to describe all activities that serve the purpose of the UNGC. After their initial report, we inquired about the indicators of the assessment tool (see Table 3 in Appendix) in semi-structured interviews. This first round of interviews surfaced the main areas of activity, and in the second round we followed-up on these clues and discussed specific aspects of the CC implementation, such as complaints procedures and training courses, directly with the staff that was in charge of handling these aspects. Hence, while the interview process was generic in its sequencing, it was unique for each company because the interview partners for the second round of interviews were only determined after the first round of interviews was completed. This flexibility took account for the fact that there is no blueprint for the CC implementation. The companies had set different priorities and they had also distributed responsibilities differently.

To reduce the effects of “political desirability,” the interview partners were then also asked to provide evidence for their statements by presenting written procedures, training manuals, etc., which we cross-checked with their interview statements. The minutes of the meeting were drafted based on the recordings of the interviews. The interview partners then had the chance to review the text and correct factual inaccuracies. In no case, however, were the interviewees allowed to completely withdraw their original statements. This cross-check merely served to ensure the correctness of statements and it also diminished the effects that various contexts can have on the interview situation (see Fontana and Frey 2005, p. 695). The case studies were thus conducted with the utmost rigor, including theoretical sampling of the cases, data triangulation, and within-case and cross-case comparisons based on detailed interview records (see Eden et al. 2005).

The Development of the Assessment Tool

The tool developed to measure the degree of CC “embeddedness” is based on Simon Zadek’s (2004) organizational learning model (see Table 3 in Appendix).Footnote 9 To this date, only a few empirical studies have been conducted on the CC engagement of companies (exceptions are, for example, the UNGC Annual review 2007). Zadek’s analysis of the sportswear manufacturer Nike describes Nike’s evolution in becoming a corporate citizen as a learning process in five stages (see Zadek 2004, p. 127). From initially denying any responsibility (defensive stage), Nike moved to adopt a policy-oriented compliance approach (compliance stage) and soon thereafter embedded societal issues into core management processes (managerial stage). Zadek reports that today Nike sees opportunities to add value to its business through the integration of societal issues in their business strategies (strategic stage) and on some issues even promotes broad industrial participation (civil stage). Thus, the study emphasizes the role of organizational learning (Banerjee 1998). As conceptions of company responsibility become more complex at successive stages of development, the requirements for the management of CC will be more demanding, as the appropriate organizational structures, processes, and systems have to be more elaborate and comprehensive. The link between CC and Zadek’s learning model is thus obvious: In early stages of development, the corporation starts acknowledging global public good problems and increasingly assumes responsibility for them (Breitsohl 2010). In the strategic stage, the corporation systematically develops solutions for these issues, yet primarily for their own operations and without systematically integrating stakeholders. In the final civil stage, the corporation then starts collaborating with stakeholders (e.g., NGOs and peers) and shares good practices. Therefore, Zadek’s description of the final learning phase, the civil stage, corresponds with Matten and Crane’s (2005) definition of CC, while earlier stages represent various interpretations of CSR. In the civil stage, corporations actively engage in collective rule-making processes on a global level and, thus, not only fulfil an economic but also a political role. This political conception of the corporation is the core contribution of Matten and Crane’s CC concept (2005). Matten and Crane were among the first authors that described the phenomenon of corporations contributing to the provision of global public goods, such as health care, human rights, and the protection of the environment. Companies engage in such rule-making activities not necessarily only for strategic reasons (see Zadek’s strategic stage) but because there is a need to fill regulatory gaps in the global business environment. The proximity to the issues, as well as the corporation’s power and resources have positioned corporations in a state-like role and for Matten and Crane, this special corporate role is precisely the novelty of the term “CC”. Zadek’s description of the civil stage fully captures this political element because it describes how corporations have moved beyond pure self-interest and how they now actively engage in developing industry solutions to challenges that states are unable or unwilling to address.

The tool to assess the current stage of development at the level of the firm consists of indicators covering the three aspects of the ideal CC concept (see Table 3 in Appendix). To assess the commitment level of CC, the mission statement, as the expression of the company’s strategic orientation, and the code of conduct, as the behavioral guideline for employees, were analyzed. In addition, we examined how the companies had distributed responsibilities for CC internally as this represents a good indicator for CC’s role and “embeddedness.” Since all companies in the sample participate in the UNGC, we also examined whether they fulfil the reporting requirements of the initiative.

For the structural and procedural implementation of CC in the company’s core business processes, we assessed whether training on CC is offered and whether it follows a systematic pattern, whether incentive structures are aligned with CC premises, whether a complaints mechanism was established to report violations of the code or clarify dilemma situations, and whether evaluations are conducted to identify the need to make corrective adjustments to the implementation process of CC (Greve et al. 2010).

The final set of indicators, the interactive level of CC, refers to the legitimacy of CC and covers the company’s level of participation in collaborative CC initiatives as well as the quality of stakeholder relationships.

These theoretically derived indicators were also cross-checked with CC experts.Footnote 10 This step in the research process served to ensure that the indicators are intelligible and coherent. The experts confirmed their relevance and comprehensiveness and provided suggestions for how to operationalize them in each learning stage. The characteristics of the indicators in each learning phase were determined by breaking down the ideal CC model (in the civil stage) into the previous stages of development. The defensive stage normally does not apply to companies which have signed publicly for a CSR/CC initiative, as they voluntarily accept some kind of responsibility beyond the sheer business responsibility. This stage is, nonetheless, included in the scale to operationalize the lower limit of CC engagement. The compliance stage represents a very limited, purely legalistic view of responsibility, referring to a policy-based compliance approach (Paine 1994). The managerial stage, as the least well-defined stage in Zadek’s learning model, merely describes a transition period while implementing CC elements into core business processes. The strategic stage discovers CC as a potential competitive advantage and turns it into an explicit business strategy (“CC as a business case”). The civil stage is characterized by integrity elements according to the integrity approach (Steinmann and Olbrich 1998) and the mission to achieve collective action on CC issues (Zadek 2004). The latter can be regarded as the particular political dimension of CC (see Table 3 in Appendix).

CC at Five Swiss MNCs: Illustration of Assessment Results

In this section, we present the results of our empirical study to illustrate that our CC assessment tool is applicable to companies that claim to engage in CC. The assessment of the five Swiss MNCs revealed interesting results. First of all, despite the similar time length of participation in the UNGC, their implementation of CC is at very different stages of development. None of the investigated companies achieved the civil stage level of CC. Most companies, however, have moved organizational attributes of CC beyond the compliance stage and are currently busy installing measures that could be placed in the managerial or even in the strategic stage of development. Due to space limitations, select cases are used to illustrate the status quo of embedding CC.

The progress of the commitment to CC, including the strategic integration of CC in the mission statement, as well as basic policy documents and the internal coordination of CC work, critically depend on the support and involvement of the top-management. The most detailed information on responsible business conduct is available on the Novartis website (http://www.corporatecitizenship.novartis.com). While the role of top-management is not explicitly mentioned on this website, the fact that such detailed information is publicly available indicates that top-management endorses this business orientation. Interviews with Novartis’s representatives supported this impression and the review of the Novartis intranet prominently features the then CEO, Daniel Vasella, who highlights the significance of CC: “Business ethics is a business topic. I take this theme very seriously.” Vasella also warns that any violation of the code of conduct and other CC policy documents will be treated as a legal violation.

In terms of the internal coordination of CC work, all examined companies could present a contact person in charge of the CC topic. In some cases, these contact persons work for the communication department and are mainly responsible for drafting the sustainability report (Nestlé, UBS), while in other cases, separate CC or CSR departments were created to ensure the proper handling of CC (ABB, Novartis, CS). The corporate representatives that work in designated CC or CSR departments, however, all reported that they are understaffed and/or isolated from core business processes. At ABB, officially only a single person runs the Corporate Responsibility Department and at the Credit Suisse (CS), a representative of the Sustainability Department said “many plans to improve the implementation of CSR are on hold because of the lack of staff to execute them.” None of the CSR departments under review has a mandate to initiate and coordinate CC-related projects, and, thus, their level of influence within the company is rather low. Instead, the decision-making power is vested in newly created CC committees at the level of the executive board. The committee proposes the CC strategy which then has to be endorsed by the board. These committees usually draw their expertise from a number of departments and representatives (e.g., the UBS has appointed environmental representatives in each business unit). The frequency of interaction, however, between the committee members and the CC or CSR departments is opaque and could not be assessed in the context of this study.

The protocols for decision-making differ among the companies. While at Novartis, CEO, Daniel Vasella, seems to be personally involved in CC topics, other CC departments struggle getting attention from top-management and oftentimes, the relationships to senior managers are informal (e.g., at ABB).

In order to design basic policies on relevant CC issues, each company must define the scope of its responsibility in its specific business context and interpret the principles they have committed themselves to (for example, the UNGC principles). However, companies have only recently started to position themselves in regard to some of the critical issues. The UBS, for example, only issued a Human Rights Declaration in 2010 and it does neither contain a reference to the International Bill of Human Rights nor any guidelines for its implementation (see also Missbach 2010). Nestlé reported in our interviews that it considers providing “access to water” as their contribution to the UNGC’s Human Rights principles. Yet, due to the rather late reflection on what the commitment to CC actually means in concrete business situations, the operationalization that should be reflected in policies, procedures, and guidelines is in most areas not yet very advanced (with the exception of the environmental domain). Nevertheless, all companies meet CC basic commitment requirements with minor differing characteristics due to the different levels of involvement by top-management. All companies refer to the UNGC on their websites, they internally assigned responsibilities for CC, and they largely integrated the UNGC principles in internal codes of conduct and basic policy documents (e.g., Human Rights policies of ABB, Novartis and UBS; see Table 1).

In contrast to the commitment dimension, the degree of implementing CC on the structural and procedural dimension varies dramatically among the selected cases. In fact, the alignments of incentive structures, training courses, and complaints procedures are taking a long time and some companies have not even really started looking at these elements yet.

From the sample, Novartis is most advanced in designing procedures that embed CC in everyday business routines. Novartis’ mission, in this respect, is to “establish, promote and enforce integrity standards throughout the company” and, to this end, it has developed innovative training material to make all employees aware of the topic. They have introduced an integrity dimension for performance appraisals to evaluate employees according to how they have reached their goals, and they define milestones for the CC implementation process and regularly evaluate their achievements. Milestones and results of the self-assessment are publicly available on the Novartis website and in their annual report (Novartis 2005). Nevertheless, even Novartis does not qualify for the civil stage on the structural and procedural dimension of CC because two critical elements are missing: the dissemination of the aligned policies and procedures to all company divisions including the supply chain, as well as the conduct of participatory sessions with stakeholders to design the procedural implementation.

The implementation status of the structural and procedural dimension of the other companies from the sample is lagging behind their commitment to CC. The aspects that are particularly weakly aligned are the operations of the Human Resources Department (to recruit, to conduct performance appraisals, to promote and to determine bonus payments depending on the respect for CC) as well as the compliance function (to signal that violating the code is treated just as strictly as violations of the law). For most companies it was not possible to identify a contact person in the Human Resources Department who could be interviewed for this study (ABB, CS, UBS) and it was also difficult to find out whether the compliance function would be able to handle cases of code violations that have no legal implications (UBS, CS). If CC policies exist, they are often not well-communicated to internal and external stakeholders and, as a result, they are not fully operational (e.g., existing complaints channels are often not used to report code violations). A representative of the CS for example reports that “many sustainability policies and procedures already exist, but it is frustrating to see how little individual employees know about them.”

None of the companies has so far fully established a management process based on a systematic impact evaluation of current CC activities. Likewise, the reporting does not follow a standardized reporting mechanism along key performance indicators. By the time of the study, only Novartis and ABB report according to the reporting criteria of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), as recommended by the UNGC (GRI 2006). Reporting according to GRI is an important step toward the standardization of CC reporting. It increases transparency, ensures comprehensiveness, and enables consumers to compare the CC performance of different companies. The other companies also use the GRI criteria as a guideline, but they argue that reporting “in accordance with GRI” would not be suitable in their industry and for their type of business (e.g., Nestlé). All companies, however, submitted “Communication of Progress” (CoP) to the UNGC office and the CoPs of ABB, Nestlé and Novartis even received awards from the UNCG office for having made “notable” contributions. All companies stated that they had recently improved their reporting on CC and that they plan to improve it further over the course of the next years. This indicates that corporations attribute a high value to the external CC communication, even though these communication efforts do not always reflect actual corporate practices (see Table 1).

The indicators measuring the “interactiveness” of the CC implementation are the least distinct. The implementation process at the examined corporations has thus far been mainly designed by corporate decision makers. The expertise of external stakeholders on certain issues was neither systematically integrated nor did the majority of the companies give stakeholders the opportunity to comment on corporate activities in the context of CC, for example, by setting up a public discussion forum. As a result, although some companies are making a serious effort to implement CC, external stakeholders remain suspicious. Some company representatives report that constructive consultations with external stakeholders take place regularly at various levels and in different departments in the organization but that these meetings would not be reported as CC engagement (Novartis). A Nestlé representative reports that meetings with civil society organizations are now often conducted confidentially to build trust and to avoid the media hype that usually develops around such meetings, which severely restricts the room for negotiation and compromise for all concerned parties. The CS has drawn up a stakeholder map for Switzerland to strategically identify groups that are influential, yet also constructive, and it keeps a record of interactions with certain external stakeholders. Some companies (e.g., ABB, Nestlé) focus on establishing solid stakeholder relationships at the local level. ABB has submitted a case story to the UNGC website concerning one of its local dialogues.Footnote 11 In addition to local dialogue structures, ABB established a stakeholder dialogue at headquarters on specific issues (e.g., human rights). However, the event is not public and only invited guests are allowed to participate. Nestlé representatives talked about local stakeholder dialogues in interviews, but the information could not be verified.

To sum up, although the “unofficial” record for engaging with stakeholders might look slightly more positive than the data collected for this study, we can still conclude that the interactive aspect of CC is at best patchy and not yet part of the implementation process of CC at the examined companies. While most companies agree with the principle of integrating stakeholders, an ABB representative, for example, argues that “if a company seeks to earn a license to operate, it really needs to be listening to as many voices as possible,” its implementation is still at an infant stage. External stakeholders are not integrated regularly but on a case-by-case basis and most of the time interaction takes place in crisis situations. The ad hoc nature of stakeholder interactions is also reflected in the rather arbitrary participation in collaborative CC initiatives. The UBS, for example, admitted that they are not taking a proactive stand in these initiatives. Instead, they tend to wait and see what peers do or until they are contacted directly by external stakeholders.

To verify this interactive aspect of the CC implementation and to get an idea of the external credibility of CC programs within these companies, a number of civil society organizations were asked to comment on their engagements (Baumann 2005; Frank 2005; Seiler 2005; Weber 2005). While their overall assessment was rather negative—as expected due to these organizations’ mission and mandate—some external stakeholders noticed a change in the behavior of companies toward NGOs. They confirmed that companies have become more open about discussing some issues and they are in general no longer as defensive as in previous years (e.g., according to external stakeholders, the CS has become more responsive in recent years while the UBS is still rather passive; see Table 1).

Table 2 captures the aggregated research results of our study.Footnote 12 It shows that the Swiss banks (CS and UBS) and Nestlé are less advanced than ABB and Novartis at embedding CC in organizational structures and procedures.

The tool has thus proven helpful to determine the status of CC program development in the respective companies. With the help of the assessment tool, a more detailed picture than produced by the initial survey (Zillich 2003) could be generated. In 2003, companies stated that they are generally advanced at implementing CC. The exemplary illustration of the implementation status of CC at ABB, Credit Suisse, Nestlé, Novartis, and UBS highlighted some significant differences between these companies and a differentiation between more and less advanced companies is now possible.

The study has also revealed a typical implementation pattern of CC: While corporations make strong public commitments to CC, the internal embeddedness of CC in daily business routines varies greatly across the sample. Only one company (Novartis) can after this assessment be considered advanced. All companies have an insufficiently developed interactive dimension of CC which creates a number of legitimacy risks for the corporation. Without the systematic involvement of stakeholders, corporations will have difficulties in defining the priorities of their CC activities and they will lack the expertise of external stakeholders to find sustainable solutions to CC issues. Even if they succeed, stakeholders will be reluctant to acknowledge the efforts since they were excluded from the process. Therefore, we can conclude that the current approach to implementing CC is highly imbalanced: The strong corporate commitments to CC raise high expectations that are, however, insufficiently backed with internal CC policies and procedures. In addition, stakeholder interactions and participation in collaborative CC initiatives remain sporadic and thus current relationships do not provide a setting for constructive exchanges over the future development of corporate CC programs. This imbalance is a cause for concern as it may hinder, or at least significantly slow down the CC learning process. Further studies could test these initial findings. In the concluding section, some of the limitations of the assessment method and avenues for further research will be described.

Concluding Remarks: Contributions, Limitations, and Suggestions for Further Research

Our study has both theoretical and practical implications. (1) We have developed an analytical tool and have integrated the leadership (commitment), organizational, and interactive dimension to assess how companies realize CC in their structures and procedures, (2) we have emphasized the dynamic component and understand CC as an organizational learning process along several stages with the civil stage as the highest stage of CC development, (3) and we link CC with the legitimacy challenge of corporations and explore their interactions with stakeholders in their strive for legitimacy. Despite the lack of companies that fully realize CC, some aspects of the implementation at each company demonstrate that the implementation of the civil stage is quite possible. The application of the assessment tool thus systematically confirms that companies engage in political activities on a global level. Our empirical findings support the anecdotal evidence on which the theoretical argument about the role of corporations in global governance was originally based (Scherer et al. 2006).

With regards to the practical implications our study shows that, in contrast to the results of the initial 2003 survey (Zillich 2003), the companies in our sample are still far from fully embedding CC in their daily business routines. While all companies made a formal commitment to CC, its implementation on a structural and procedural level varies extensively among the companies. While some companies have started to align their business procedures with the requirements of the UNGC, other companies still treat CC as an isolated topic managed by a few individuals which is not yet embedded in the corporate culture. On the interactive level, none of the companies seems to systematically integrate stakeholders in the design and discussion of CC activities. As a result, the corporate legitimacy rather suffers from the current CC engagement than it profits. Therefore, corporations should analyze their CC implementation and identify the elements that require further efforts, particularly those that involve relationship-building.

The research has a number of methodological and practical limitations. On a methodological level, many of the points of critique apply to Zadek’s model that are typically advanced against stage models (Stubbart and Smalley 1999). Zadek’s model assumes that firms progress through stages sequentially while there might be multiple paths through these stages. The model neglects the motives and events that drive the progression through stagesFootnote 13 and it heavily simplifies a complex implementation process as no company is at any single stage of CC but some aspects of the implementation process are at the strategic stage, while others are still in the compliance stage. In addition, Zadek developed his stage model for CC by analyzing only one case. Whether the development of Nike is also representative for companies of different industries remains to be tested. For example, Nike’s main driver for organizational learning was the continuous pressure of NGOs, and it is questionable whether companies that are less exposed to public scrutiny would have made such progress (den Hond and de Bakker 2007; Zyglidopoulos 2002). The advantage of Zadek’s stage model, however, is that it helps structuring the empirical findings and it suggests which aspects need to be strengthened to make progress in the CC implementation process.

On a practical level, the research was limited by the time constraints of company representatives and the initial difficulty to build trust. It was relatively easy to gain access and to arrange a first meeting with CC managers in the UNGC companies. Company representatives were, however, very reluctant when it came to moving beyond the initial round of interviews to a more thorough assessment of existing documents, processes, and procedures. This suspicion was probably caused by NGO exposés that companies had experienced in the past. In order to assess the actual status quo of CC implementation, it was necessary, though not just to record the attitudes of the company representative in charge of CC, but also to review formalized procedures and discuss these with managers from various functional departments. To enter this second round of the empirical study, several rounds of meetings were required to build trust. Nevertheless, the second round of empirical assessment could not be fully completed at each company due to the time constraints of the company representatives. Yet, the data quality suffices to draw our implications from the research results.

The timing of our data collection also represents some limitations to our findings. Our data were collected in 2007, 7 years after the launch of the UN Global Compact and a couple of years before the start of the recent world economic crisis. We believe that in 2007, MNCs’ awareness for CSR issues was greater than ever before. Various corporate scandals had underlined the significance of establishing CSR policies and procedures and many MNCs had started to publically report on their CSR engagement. CSR initiatives had mushroomed and were growing in size and popularity. It would have been interesting to collect another set of data during and after the economic crisis to analyze its effect on the companies’ CSR engagement. In fact, it could have provided the litmus test for the robustness of the corporate engagement in CSR. If corporations had indeed embedded guidelines for responsible business conduct in organizational structures and procedures (and in fact practice CC), the effects of economic downtimes on the corporate engagement should be minimal.

This study is a first attempt to assess CC and the number of companies of our study was very small (five companies). To further test and refine the assessment tool, more studies across different sectors, different countries, and different-sized firms are needed. One important aspect that featured in the research was that an additional policy issue-specific assessment (e.g., along human rights, social, or environmental issues) might be a useful supplement to the company approach suggested by Zadek’s model. The empirical study in Switzerland indicated that companies are, for example, more advanced in designing and implementing policies and procedures in the environmental realm than in the human rights realm. Stakeholder groups also differ in these issue areas and, while stakeholder engagement might be institutionalized in one area, it might still be absent in others. Consequently, the “embeddedness of CC” might be at different learning stages, depending on the policy issue. Further research could be focused on adapting the model to the unequal speed of implementation in the issues areas addressed by the UNGC (human rights, labor, environment, and corruption).

Moreover, to circumvent the difficulties of data gathering at company level, the tool could be presented as a self-assessment tool, for companies to assess their status of development on their own (and confidentially, if they wish) and to design the next steps of their CC implementation according to the results.

Notes

See, for example, the Fortune Global 500 ranking, which displays the world’s largest companies according to how well they conform to socially responsible business practices (http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/2006/10/30/8391850/index.htm).

A philanthropic understanding of CC is, for example, reflected in the 2007 Sustainability Reports of Koc Holding (CC is mainly operated from the independent Vehbi Koc foundation which sponsors the arts, etc., see http://www.koc.com.tr/en-US/SocialResponsibility/SocialProjects/) or the Oil and Natural Gas Company (CC is mainly understood as community affairs, including building hospitals and schools; see http://www.ongcindia.com/community.asp).

The CC “business case” is, for example, highlighted on the websites of Nestlé (“creating shared value,” see http://www.Nestlé.com/SharedValueCSR/Overview.htm) and Philips (focus on “green innovations,” see http://www.philips.com/about/sustainability/oursustainabilityfocus/index.page).

See, e.g., Huffington Post: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2010/05/17/bp-safety-violations-osha_n_578775.html (19.07.2010).

For an alternative legitimacy concept see, e.g., Wolf 2005. In contrast to what is suggested in our paper Wolf treats legitimacy as an observable and countable phenomena that can be measured objectively.

In June 2011, the United Nations Human Rights Council unanimously endorsed a set of Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. The Guiding Principles define the respective roles of businesses and governments to ensure that companies respect human rights in their own operations and through their business relationships. The Guiding Principles were developed by the Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General for Business and Human Rights, Professor John Ruggie of Harvard Kennedy School, over the 6 years of his UN mandate from 2005 to 2011.

For an overview of the current debate on the “sphere of influence” see, e.g., Gasser (2006). Gasser argues against a “top-down” definition that is based on objective criteria. He proposes instead to define the “sphere of influence” in discourse and according to the specifics of the situation. Statement available at http://blogs.law.harvard.edu/ugasser/category/sphere-of-influence/.

The implementation of the UNGC at SMEs is analyzed in a subsequent study.

Alternative models of “stages” of corporate citizenship on a firm level were, for example, developed by Post and Altman (1992). They describe the progressive integration of environmental policies in company policies.

The following experts were interviewed for this study: Auret van Heerden, President and CEO of the Fair Labor Association, Claude Fussler, Consultant and Senior Advisor to the UN Global Compact, Prof. Dr. Klaus Leisinger, President and CEO of the Novartis Foundation for Sustainable Development and Special Advisor of Kofi Annan for the UNGC, Dr. York Lunau, former contact point for the Swiss UNGC network.

Case study on the value of stakeholder engagement for ABB in Sudan, see: http://www.unglobalcompact.org/data/ungc_case_story_resources/doc/EF5ECE7A-C772-4A60-A3C1-458CC74D5765.pdf.

The aggregated results are calculated as follows: each learning stage is operationalized with increasing points for more advanced stages of development (defensive stage: 1, compliance stage: 2, managerial stage: 3, strategic stage: 4, and the civil stage: 5). The items i d within each of the three dimensions are all weighted equally and the average learning score LScd for each company c (c ∈ C; C = {ABB; CS; Nestlé; Novartis; UBS}) and dimension d (d ∈ D; D = {commitment; structural & procedural; interactive}) is calculated. The companies will be categorized in the defensive stage for a learning score LScd < 1.5; in the compliance stage for 1.5 ≤ LScd < 2.5; in the managerial stage for 2.5 ≤ LScd < 3.5; in the strategic stage for 3.5 ≤ LScd < 4.5; and in the civil stage for 4.5 ≤ LScd. For example, in the structural and in the procedural dimension, Novartis scores 4 (strategic stage) in five out of six items and two (compliance stage) in one item. The aggregated learning score for Novartis for the structural and procedural dimension LSNovartisSPS is calculated as follows: (5 × 4 + 1 × 2): 6 = 3.66. The scores were rounded to the first decimal number behind the comma. Therefore, the final score for Novartis in the structural and procedural dimension is 3.7 and on the aggregated level, the company will thus be categorized in the strategic learning phase. The precise results of the LScd of the commitment dimension are ABB (4.0), CS (2.5), Nestlé (2.5), Novartis (3.5), UBS (3.0); for the structural and procedural dimension ABB (2.7), CS (2.3), Nestlé (2.3), Novartis (3.7), UBS (2.2); and for the interactive dimension ABB (3.5), CS (2.5), Nestlé (3.0), Novartis (3.0), UBS (2.0).

For an advanced version of Zadek’s stage model specifically addressing the trigger mechanisms that make a firm move from one stage to the next, see Mirvis and Googins (2006).

References

Ashforth, B. E., & Gibbs, B. W. (1990). The double-edge of organizational legitimation. Organizational Science, 1, 177–194.

Banerjee, S. G. (1998). Corporate environmentalism: Perspectives from organizational learning. Management Learning, 1998, 147–164.

Banerjee, S. B. (2007). Corporate social responsibility. The good, the bad and the ugly. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Baumann, D. (2005). UBS und Credit Suisse Group und der Global Compact. Eine Analyse des Unternehmensumfeldes zur Klärung des bluewashing Vorwurfes. Unpublished semester paper. University of Zurich, Switzerland.

Baumann-Pauly, D., Wickert, C., Spence, L., & Scherer, A. G. (2011). Organizing corporate social responsibility in small and large firms -size matters, University of Zurich, Chair of Foundations of Business Administration and Theories of the Firm, Working Paper No. 204, December 2011.

Braithwaite, J., & Drahos, P. (2000). Global business regulation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Breitsohl, I. (2010). The roles of preventability and conformance in organizational responses to legitimacy threats. Working Paper. University of Wuppertal.

Brown, M. E., Trevino, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Making Processes, 97, 117–134.

Crane, A., Matten, D., & Moon, J. (2008). The emergence of corporate citizenship: Historical development and alternative perspectives. In A. G. Scherer & G. Palazzo (Eds.), Handbook of research on global corporate citizenship (pp. 25–49). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Detomasi, D. A. (2007). The multinational corporation and global governance. Modelling global public policy networks. Journal of Business Ethics, 71, 321–334.

Deva, S. (2006). Global compact: A critique of the UN’s ‘public-private partnership for promoting corporate citizenship. Syracuse Journal of International Law and Communication, 34, 107–151.

den Hond, F., & de Bakker, F. G. A. (2007). Ideologically motivated activism. How activist groups influence corporate social change activities. Academy of Management Review, 32, 901–924.

Eden, L., Hermann, C., & Li, D. (2005). Bringing case studies back. In Qualitative research in international business. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Studies Association, Hilton Hawaiian Village, Honolulu, Hawaii.

Fernandez, M. F., & Randall, D. M. (1992). The nature of social desirability response effect in ethics research. Business Ethics Quarterly, 2, 183–205.

Fontana, A., & Frey, J. H. (2005). The interview. From neutral stance to political involvement. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 695–727). London: SAGE.

Frank, D. (2005). Nestlé und der UN Global Compact—analyse des unternehmensumfeldes seit dem Beitritt. Unpublished semester paper. University of Zurich, Switzerland.

Garriga, E., & Mele, D. (2004). Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. Journal of Business Ethics, 53, 51–71.

Gasser, U. (2006). Corporate social responsibility. What is the meaning of the ‘sphere of influence’. Law and Information. http://blogs.law.harvard.edu/ugasser/category/sphere-of-influence.

Global Reporting Initiative, GRI. (2006). UN Global Compact and Global Reporting Initiative form strategic alliance move to further advance responsible corporate citizenship. Press release, Amsterdam 9 October, 2006. http://www.globalreporting.org/NewsEventsPress/PressResources/PressReleaseUNGC-GRI.htm.

Greve, H., Palmer, D., & Pozner, J. (2010). Organizations gone wild: The causes, processes, and consequences of organizational misconduct. Academy of Management Annals, 4, 53–107.

Hsieh, N. (2009). Does global business have a responsibility to promote just institutions? Business Ethics Quarterly, 19, 251–273.

Kaul, I., Conceicao, P., Le Goulven, K., & Mendoza, R. U. (Eds.). (2003). Providing public goods. Managing globalization. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kaul, I., Grunberg, I., & Stern, M. A. (Eds.). (1999). Global public goods. International cooperation in the 21st century. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lafarge 2009: Sustainability Report 2009. http://www.lafarge.com/05032010-publication_sustainable_development-Sustainable_report_2009-uk.pdf.

Laufer, W. S. (2003). Social accountability and corporate greenwashing. Journal of Business Ethics, 43, 253–261.

Laufer, W. S. (2006). Corporate bodies and guilty minds: The failure of corporate criminal liability. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Logsdon, J. M., & Wood, D. J. (2002). Business citizenship: from domestic to global level of analysis. Business Ethics Quarterly, 12, 155–187.

Matten, D., & Crane, A. (2005). Corporate citizenship: Toward an extended theoretical conceptualization. Academy of Management Review, 30, 166–179.

Matten, D., Crane, A., & Chapple, W. (2003). Behind the mask: Revealing the true face of corporate citizenship. Journal of Business Ethics, 45, 109–120.

Mirvis, Ph, & Googins, B. (2006). Stages of corporate citizenship. California Management Review, 48(2), 104–125.

Missbach, A. (2010). Without Map or Compass. Credit Suisse, UBS, and Human Rights. A Declaration of Berne Discussion Paper.

Murillo, D., & Lozano, J. (2006). SMEs and CSR. An approach to CSR in their own words. Journal of Business Ethics, 67, 227–240.

Nolan, J. (2005). The United Nations Global Compact with business: Hindering or helping the protection of human rights? The University of Queensland Law Journal, 24, 445–466.

Novartis (2005). Corporate citizenship at Novartis begins with the success of our core business. http://www.corporateregister.com/a10723/ni05-ann-swi.pdf.

Paine, L. S. (1994). Managing for organizational integrity. Harvard Business Review, 72(February), 106–117.

Palazzo, G., & Scherer, A. G. (2006). Corporate legitimacy as deliberation: A communicative framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 66, 71–88.

Post, J. E., & Altman, B. W. (1992). Models for corporate greening: How corporate social policy and organizational learning inform leading-edge environmental management. In J. Post (Ed.), Research in Corporate Social Policy and Performance, (Vol. 13, pp. 3–29). JAI Press: Greenwich, CT.

Randall, D. M., & Fernandes, M. F. (1991). The social desirability response bias in ethics research. Journal of Business Ethics, 10, 805–817.

Santoro, M. A. (2000). Profits and principles. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Scherer, A. G., Palazzo, G., & Baumann, D. (2006). Global rules and private actors. Toward a new role of the TNC in global governance. Business Ethics Quarterly, 16, 505–532.

Scherer, A. G., Palazzo, G., & Matten, D. (2009). Introduction to the special issue. Globalization as a challenge for business responsibilities. Business Ethics Quarterly, 19, 327–347.

Scherer, A. G., Palazzo, G. & Seidl, D. (2008). Legitimacy strategies as complexity reduction in a post-national world: A systems-theory perspective. Paper presented at the Organization Studies summer workshop, Cyprus.

Seiler, A. (2005). ABB und der UN Global Compact—analyse des unternehmensumfeldes seit dem Beitritt. Unpublished semester paper. University of Zurich, Switzerland.

Sethi, P. (2003). Global compact is another exercise in futility. Financial Express, September 8.

Silverman, D. (2005). Doing qualitative research. A practical handbook. London: SAGE.

Spence, L. (2007). CSR and small business in a European policy context: The five ‘C’s of CSR and small business research agenda. Business and Society Review, 112, 533–552.

Stansbury, J., & Barry, B. (2007). Ethics programs and the paradox of control. Business Ethics Quarterly, 17, 239–261.

Stake, R. E. (2005). Qualitative case studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 443–466). London: SAGE.

Steinmann, H. (2007). Corporate ethics and globalization. Global rules and private actors. In G. Hanekamp (Ed.), Business ethics of innovation (pp. 7–26). Berlin: Springer.

Steinmann, H., & Olbrich, Th. (1998). Ethik-management: Integrierte steuerung ethischer und ökonomischer prozesse. In G. Blickle (Ed.), Ethik in organisationen (pp. 95–115). Göttingen: Wallstein.

Stubbart, C., & Smalley, R. (1999). The deceptive allure of stage models of strategic processes. Journal of Management Inquiry, 8(3), 273–286.

Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review, 20, 571–610.

Waddock, S. (2008). Corporate responsibility/corporate citizenship: The development of a construct. In A. G. Scherer & G. Palazzo (Eds.), Handbook of research on global corporate citizenship (pp. 50–73). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Weber, M. (2005). Novartis und der UN Global Compact—analyse des unternehmensumfeldes seit dem Beitritt. Unpublished semester paper. University of Zurich, Switzerland.

Windsor, D. (2006). Corporate social responsibility: three key approaches. Journal of Management Studies, 43, 93–114.

Wolf, K. D. (2005). The potential and limits of private self-regulation as an effective and legitimate mode of governance. Journal for Business, Economics & Ethics, 6(1), 51–68.

Zadek, S. (2004). The path to corporate responsibility. Harvard Business Review, 82(December), 125–132.

Zillich, H. (2003). Die Umsetzung des UN Global Compact in der Schweiz. Erhebung über die Tätigkeiten von acht beteiligten Schweizer Unternehmen. Unpublished semester paper. University of Zurich, Switzerland.

Zürn, M. (2000). Democratic governance beyond the nation state: The EU and other international institutions. European Journal of International Relations, 6(2), 182–221.

Zürn, M. (2002). From interdependence to globalization. In W. von Calsnaes, T. Risse, & B. Simmons (Eds.), Handbook of international relations (pp. 235–254). London: SAGE.

Zyglidopoulos, S. C. (2002). The social and environmental responsibilities of multinationals: Evidence from the Brent Spar case. Journal of Business Ethics, 36, 141–151.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support by the Swiss National Science Foundation for the project “Corporate Legitimacy and Corporate Communication—A Meso Level Analysis of Organizational Structures within Global Business Firms” (Projekt No. 100014_129995).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Baumann-Pauly, D., Scherer, A.G. The Organizational Implementation of Corporate Citizenship: An Assessment Tool and its Application at UN Global Compact Participants. J Bus Ethics 117, 1–17 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1502-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1502-4