Abstract

Despite the recent paradigmatic shift in conservation science, protected areas (PAs), which are associated with seminal conservation strategies, remain a key tool for achieving biodiversity conservation. Nevertheless, PAs’ effectiveness as conservation measures is undermined by conflicts arising within their socio-ecological systems. Potential reasons for the negative impact of the conflicts include the tendency of researchers to emphasise managerial or behavioural aspects of conservation conflicts, while neglecting to develop theoretical foundations for conflict analysis. We aimed to critically review existing conceptual frameworks applied within the broadly defined field of conservation conflicts and to develop a new more comprehensive framework that better reflects contemporary identified challenges within nature conservation. We particularly proposed and emphasised the integration of a geographical perspective within existing interdisciplinary approaches for the application to PA settings. We systemised and unified conflict-related terminology, assessed the contributions and limitations of existing frameworks and identified critical gaps in the field. These gaps are: inadequate recognition of the spatial aspects of conflict analysis, a lack of consistency between individual-level and community-level frameworks and a lack of systematic linkages among the main structural attributes of conflicts, such as determinants, interests or types of conflicts. We systematically distinguished 26 conflict-related terms, including: conflict frames, images, orientations, factors, categories, issues, potential, or intensity. Our framework covers three major conflict components (determinants, dimensions, levels) and foregrounds the socio-psychological and spatial characteristics of PA conflicts, while enabling systemisation of existing conservation conflict typologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Along with sound governance and scientific inputs into conservation endeavours (Cumming 2018), cooperation among concerned stakeholders is widely considered to be a factor contributing to the success of such endeavours (Berkes 2004; Guerrero et al. 2015; Soulé 1985). Despite this consensus, social networks within many socio-ecological systems (SES) remain conflictual rather than cooperative (see Baynham-Herd et al. 2018; Kovács et al. 2016; Martin et al. 2016; Young et al. 2016a; Yusran et al. 2017 for the most recent examples). Although there is a large body of literature on conservation conflicts (see Redpath et al. 2015a for the latest monography), most of these studies lack a solid theoretical foundation (Yusran et al. 2017). One of many potential reasons for this situation is the prevailing tendency of researchers to focus on the managerial or behavioural aspects of conservation conflicts (Baynham-Herd et al. 2018; De Pourcq et al. 2017; Ravenelle and Nyhus 2017; Young et al. 2016b) that are often context-dependent (Dickman 2010; Hellström 2001; Madden and McQuinn 2014; Manfredo and Dayer 2004). This is in contrast to another potential approach aiming at developing frameworks that can address the challenge of context dependence. Yet, researchers investigating the social aspects of nature conservation still prefer to apply established principles to different empirical studies (Cumming 2018).

Over the last decade, a major paradigmatic shift has occurred in conservation science (Kareiva and Marvier 2012; Mace 2014; Palomo et al. 2014) that includes the adoption of more integrative perspectives in place of a predominant focus on protected areas (PAs), as they were traditionally defined in terms of authoritative governance. At the same time, seminal conservation strategies continue to prioritise PAs as key tools for biodiversity conservation (Jones et al. 2017; Watson et al. 2014) at both the global scale (CBD 2010; Di Marco et al. 2016) and the continental scale (European Parliament 2012; García-Llorente et al. 2018). They are considered crucial (Sandwith et al. 2014) for halting the process of biodiversity loss (Di Marco et al. 2016; Geldmann et al. 2013) and for reducing climate change (Dudley et al. 2010; IUCN 2012; Nogueira et al. 2018; Roberts et al. 2017). Moreover, a recently adopted SES approach (Cumming 2016; Cumming et al. 2015; Palomo et al. 2014) highlights their role in improving people’s well-being at local levels (Dudley 2008; Sandwith et al. 2014; Watson et al. 2014). In a context of expanding PAs driven by global policies (CBD 2010; Di Marco et al. 2016; Venter et al. 2014), potential outbreaks of conservation-related conflicts are inevitable due to the extraordinary character of this land use change (Baynham-Herd et al. 2018). These conflicts do not necessarily result from the multifunctionality of PAs, defined in terms of specific type of land use (Dudley and Stolton 2008). Rather, the conflicts may be attributed to a well-recognized phenomena of trade-offs occurring among different ecosystem services (Maes et al. 2012; Martín-López et al. 2014; Mouchet et al. 2017) and valuations of PA nature’s contributions (Gómez-Baggethun et al. 2010; Pascual et al. 2017; Raymond and Kenter 2016). Additionally, both ecosystem services and their valuations are different inside and outside of PAs (Castro et al. 2015; Hummel et al. 2019). As the expansion of PAs has already received attention from scholars within the field of conservation planning and management (Butchart et al. 2015; Venter et al. 2014), reassessment of established knowledge on conservation conflicts is timely in that respect.

Recent literature on conservation conflicts offers some invaluable state-of-the-art conceptual frameworksFootnote 1 (Dickman 2010; Madden and McQuinn 2014; Redpath et al. 2013; White et al. 2009). However, a reassessment of their adequacy in providing a well-grounded theoretical background for empirical studies on conservation conflict is required. The frameworks rarely refer to previously published ones, so their constitutive role within the theoretical progression of this research field is questionable. Systematic and comparative critiques of these frameworks are also lacking. What is specifically needed is an examination of the extent to which the frameworks reflect an interdisciplinary approach to the challenges discussed. An interdisciplinary approach was strongly advocated by Redpath et al. (2015a) in their latest monograph on conservation conflicts. Yet despite their comprehensive review of various disciplinary-specific perspectives on conservation conflicts, it is striking that these authors did not provide a section with geographical inputs on this topic.

We argue that a geographical perspective is essential to address challenges linked to the unclear role of PAs in the field of conservation science and to develop a more comprehensive conceptual framework for the analysis of conservation conflicts. According to International Union for Conservation of Nature, PAs are ‘clearly defined geographical spaces, recognised, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values’(Dudley 2008, p. 8). As such, PAs (and their SES) are geographical settings, where biodiversity conservation strategies are realized, usually in a form of multi-level conservation governance (Newig and Fritsch 2009). Despite various advantages, this approach implies mismatches across social, natural and administrative systems (Cash et al. 2006) that are ultimately exposed through the way PA borders are demarcated. The mismatch is expected to further amplify along the process of PA expansion, which is another geographical factor for conflict emergence. Finally, PAs are proper settings for adoption of constructionist/constructivistFootnote 2 frameworks to conservation conflict analysis (Hellström 2001; Ide 2016). This is because each type of PA legal designation (Dudley 2008) includes pre-defined limitations to PA stakeholders, both in terms of their merit and spatial extent. As such, they may be easily juxtaposed with stakeholders’ subjective images of the conflict determinants. Given the unique character of conservation conflicts in the PA settings, we propose they could be directly labelled as ‘protected area conflicts’. Despite the multiple ways in which conservation conflicts have been framed (see Baynham-Herd et al. 2018 for a recent review of these notions), ‘PA conflicts’ is missing within these conceptualisations.

Our overall aim is to critically review current conceptual frameworks in the broadly defined field of conservation conflicts and to propose a new framework that avails of existing frameworks, but better reflects contemporary challenges in nature conservation. We particularly emphasise the applicability of the proposed framework to a PA context, as it is reflected in the framing of the concerned subject as ‘protected area conflicts’. Thus, we emphatically integrate a geographical perspective with other interdisciplinary approaches. Specifically, we attend to (1) the multi-level nature of conservation conflicts along a spatial scale, (2) various types or properties of conflict, including spatial and non-spatial characteristics, (3) the problem of spatial dynamics and the blurred boundaries between socially constructed values or interests in the context of maintaining stability of the PA borders. To comprehensively meet the overall aim of the study, we unified and reconstructed the terminology applied in theoretical approaches, and summarised theoretical assumptions that we determined crucial when studying conservation conflicts. Last, we discuss selected settings in which the proposed framework can be successfully applied.

Methodology

During the first phase of the study, we reviewed peer-reviewed theoretical articles on conservation conflicts. For the data-collection stages of the reviewing process, we followed the rules of a systematic quantitative literature review, which consisted of: defining topic, formulating research questions, identifying keywords, identifying and searching a database, and reading and assessing publications (Pickering and Byrne 2014). In light of considerable ambiguity in the framing of conservation conflicts (Baynham-Herd et al. 2018; Redpath et al. 2013, 2015b; Young et al. 2010), we identified topics of interest broadly as ‘conservation’, ‘biodiversity’, ‘human–wildlife’ and ‘environmental’ conflicts. When defining the topics, we referred to the general term of ‘conservation conflicts’ and its two component terms: ‘human-wildlife conflicts’ and ‘biodiversity conflicts’, which correspond to two dominant research directions within the general field.Footnote 3 Moreover, given that the term ‘conservation conflicts’ is sometimes defined as a specific type of ‘environmental conflicts’ (White et al. 2009), we also included papers that refer to the broader term. By contrast, we did not consider studies focused on ‘land use conflicts’ which ‘conservation conflicts’ are not conceptualized as a specific type of. Last, overly narrow studies on ‘natural resources conflicts’, in which conflict determinants were reduced only to an economic group were not included.

Although the ISI Web of Knowledge database tends to be used for systematic reviews in environmental social science (e.g., Baynham-Herd et al. 2018; Blicharska et al. 2016), we searched the Scopus database. We did so intentionally because of the broad coverage of the latter database and its sophisticated search options (Leung et al. 2015; Restall and Conrad 2015). We found these criteria crucial for conducting a successful literature review performed using a qualitative approach.

The search was conducted in December 2017. Specifically, we used the TITLE-ABS-KEY fields and two of the following sets of keywords: (‘biodiversity conflict*’ OR ‘conservation conflict*’ OR ‘human–wildlife conflict*’ OR ‘environmental conflict*’) AND (framework* OR theor* OR concept* OR approach* OR review* OR model* OR defin*). Accordingly, we compiled a list of 1157 documents, which were then sorted using the “cited by (highest)” options. Titles and abstracts of the first 200 most cited papers were screened to target papers referring to the theoretical aspects of our topic of interest, while excluding those focusing on specific study areas, narrowly defined aspects of conflicts (e.g., the impacts of specific species or particular harmful investments), or on conflict management rather than on conflict identification and analysis. The number of screened papers was limited due to analytic capabilities of the researchers, yet our first sample was still twice as high as the sample of 100 papers addressed in another recent review paper in the field (Baynham-Herd et al. 2018). Moreover, we repeated this process for papers published in 2016 and 2017 to ensure inclusion of newer influential papers that were not yet widely cited. As a consequence of the fixed search criteria, a group of studies, although influential, intentionally remained beyond the scope of the review (e.g., classical theories of conflicts within the social sciences, multi-criteria decision analysis models, or formal models in game theories; see more in Online Appendix 1).

Initially, of almost 400 screened papers, we found only 18 that fulfilled criteria of our review and which we downloaded for detailed assessment. During the reading process, we applied a snowball sampling strategy (Lecy and Beatty 2012) that entails searching for additional papers referred to as significant in the first set of selected papers. Additionally, some initially selected papers were discarded during the detailed reading phase. Ultimately, 17 papers were selected, of which 12 included some kind of conceptual framework for studying conservation conflicts, 3 specifically referred to terminological issues, and 2 addressed the role of science in studies of environmental conflicts (the latter 2 aspects were also addressed in the first 12 papers). A final reading process was conducted with the assistance of the NVivo 10 software (Online Appendix 1).

As the sample size was small, we used a traditional narrative review methods for data analysis, which based on expert comparisons of the reviewed sources, descriptive gap analysis and narrative description of the results (Pickering et al. 2015). Specifically, we reviewed papers from the following perspectives: (1) definitions of conflicts, (2) the variety of terms and attributes used to describe the overriding notion of conflicts, (3) the thematic study context, (4) contributions of the framework to overall conceptual knowledge on conservation conflicts, and (5) limitations of the framework. The results were grouped in the form of tables, including one that juxtaposed state-of-the-art approaches to conflict-related terminology with our own suggestions on how to understand them (“Unification of conflict-related terminology” section). During the second phase, all of the state-of-the-art conceptual frameworks have been described, assessed, critically compared (“State-of-the-art frameworks for studying conservation conflicts” section), adjusted, combined and finally redefined, contributing to the formation of a single novel integrative conceptual framework for investigating PA conflicts (“Proposed integrated conceptual framework for studying protected area conflicts” section). When graphically depicting the framework, we draw on some of the earlier models that we considered best presenting flows among crucial non-behavioural conflict attributes. However, an eventual framework presents a novel design and content, in comparison with earlier state-of-art proposals. Finally, we discuss the most critical assumptions that we believe should guide any research process relating to conservation conflicts in PAs. The whole process of developing the framework as well as its outputs have been validated by two independent experts from the fields of human geography and environmental justice.

Results

Unification of conflict-related terminology

Conflicts per se and conflict-related terms were differently defined in the reviewed papers. A review of definitions of ‘conflicts’ that authors of studies on conservation conflict had themselves proposed or cited from other sources revealed the presence of at least two dominant approaches for understanding this notion (see Online Appendix 2 for a comprehensive list of definitions). Some of the authors (e.g. Ozawa 1996; Pruitt and Rubin 1983) used the term ‘conflict’ to refer to a ‘perceived divergence of interests’, whereas others (e.g. Deutsch 1973; Tjosvold and van de Vliert 1994) noted that besides the divergence in the perceptions actions are another necessary qualifying criteria of conflicts. The definition that we favoured in this review refers specifically to three elements of a conflict: (1) involvement of two or more parties, (2) competing interests of these parties, and (3) perceptions of these interests that are influenced by a variety of determinants. That was the most widely used conceptualisation in the reviewed papers focusing on conservation conflicts (originally adopted from a FAO 1998 report; Redpath et al. 2013, 2015b; White et al. 2009; Young et al. 2010). Importantly, this definition does not contain any specific references to temporal dimension of conflicts, nor to human actions (see “The assumption of coverage of only the identiication of a conflict” section for the modified version). As revealed by this review, the action-based approach mentioned above is more often used in studies oriented towards conflict management (ref. Walker and Daniels 1997).Footnote 4

The liveliest debate on terminology within this field has focused on the framing of ‘human–wildlife interactions’. The term ‘human–wildlife conflicts’ (HWCs) was popularised by American scholars (e.g. Conover 2002; Madden 2004; Manfredo and Dayer 2004) but has been criticised by many others because it suggests that non-human beings (i.e., wildlife) ‘work’ as one of the two conflicted parties. This implied meaning negates an important ontological assumption that conflicts can only emerge among people (Peterson et al. 2010; Redpath et al. 2013, 2015b; White et al. 2009). Along with this critique, a trend of gradual modification of the HWC term is observable in the literature (Peterson et al. 2010). Specifically, terms that are more general (human–wildlife coexistence; Madden 2004) or narrower (human–wildlife impacts; Redpath et al. 2015b)Footnote 5 have been introduced, and the renowned journal, Human–Wildlife Conflicts has been renamed as Human–Wildlife Interactions (Peterson et al. 2010).

The review reveals that HWCs are the most prevalent example of the above described lexical imprecision, but there are others. ‘Protected area–community conflicts’ (Liu et al. 2010) and ‘park/people conflicts’ (Stern 2008) are other noteworthy examples in light of the topic of this paper. These particular terms are not necessarily incorrect from a logical perspective (‘PAs’ or ‘parks’ may represent institutions that are often stakeholders in conflicts). However, we recommend the use of the term ‘protected area conflicts’ for labelling such conflicts. The proposed approach is more consistent with the prevailing mode of framing conflicts with a descriptive word referring to the conflict setting (e.g., ‘conservation conflicts’, ‘biodiversity conflicts’ and ‘land-use conflicts’) and not to the parties involved. Moreover, such two-element terms imply that the conflict is limited to only two parties, which is rarely the case in a PA setting.

Even more ambiguity is observable in relation to specific conflict-related terms within the literature. Some of these terms need to be clarified because despite their apparent synonymity, they differ in terms of their origins and the contexts of their use. Examples (in Table 1 and Online Appendix 3) include: (1) anthropologically-oriented ‘conflict cultures’ (Hellström 2001), stakeholder-oriented ‘conflict frames’ (Shmueli 2008) and context-oriented ‘conflict settings’ (Walker and Daniels 1997), (2) value-driven ‘conflict orientations’ (Fulton et al. 1996) and rationally formulated ‘conflict preferences’ (Al-Mutairi et al. 2008), and (3) ‘conflict stages’ (Keltner 1987) that indicate processual approach to conflicts and ‘conflict states’(Hipel and Walker 2011) that are used in game theory analysis.

Specific terms are used to address the major components of conflicts (factors or aspects as well as dimensions) and their case-specific attributes—conflict categories. Further clarification is needed on terms that, in our opinion, should be consistently positioned as outcomes of the abovementioned components. The term ‘conflict interests’ requires particular attention because it was directly referred to in the majority of definitions of conflicts (see Online Appendix 2), but rarely featured in the reviewed conceptual frameworks. In this context, a useful illustrative framing of this term (and interlinked ones, i.e., conflict interests, issues, and positions) can be drawn from the field of conflict management, in which interests are defined as stakeholders’ reasons (why?) for taking certain conflict positions (how?) (Delli Priscoli 1997) that concern conflict issues (what?) (Walker and Daniels 1997).

Our intention was also to highlight conflict-related terms that have a certain ‘common sense’ meaning, while being used in a much more specific manner within the academic papers (Table 1, Online Appendix 3). For instance, the term ‘conflict intensity’ relates to behavioural manifestations of conflict (often describing ‘overt’ conflicts), which means the more destructive actions or the more negative impacts of these actions take place, the more intense a conflict is (see White et al. 2009). Whereas, the term ‘conflict potential’ should be used to describe the complexity of structural (i.e. non-behavioural) attributes of conflicts (White et al. 2009). Such understood ‘high complexity’ does not necessarily mean high vulnerability for conflict to transform into an overt one, because this condition is proved to be highly culture-dependent (Hellström 2001). However, diversity of values and interests of affected parties, that are in conflict with one another and change over time, makes the problem hardly possible to be formulated, and ultimately to be solved, which corresponds to theoretical assumptions of ‘wicked problems’ (Xiang 2013). Finally, the term ‘conflict outcomes’ is specifically used to describe the consequences of conflict behaviours of the conflicted parties (White et al. 2009), nonetheless ‘outcomes’ per se may have various connotations (e.g., we use this word in the context of outcomes of structural conflict analysis—see Fig. 1).

The meanings of some common terms are not established within the field of conservation conflicts, which requires the following clarification. For instance, ‘conflict structure’ is used as a general term that encompasses the entire set of conflict attributes presented in the form of a conceptual framework. ‘Conflict process’ is often used to emphasise a dynamic approach to conflicts (as opposed to static ‘conflict images’), whereas ‘manifestations of conflicts’ refers to incidents demonstrating conflict in a behavioural or outcome-related sense. Last, irrespective of distinctions drawn by game theorists (Hipel and Walker 2011), the terms ‘conflict stakeholders’ and ‘conflict actors’ are applied interchangeably, referring to anyone (an individual or group) who is affected by certain decisions and actions, who has the power to influence their outcome (Freeman 1984) and who holds a relevant view of the conflict.

State-of-the-art frameworks for studying conservation conflicts

Only 10 frameworks met our assumptions relating to the inquiry on state-of-the-art frameworks for studying conservation conflicts (see descriptions along with their contributions and limitations in Table 2 and their graphical models in Online Appendix 4). Three of the reviewed papers discussed one of the frameworks, namely the triangle of conflict dimensions, whereas each of the other frameworks were only featured in one paper, respectively. Although four of the frameworks, including the triangle and the frameworks developed by Patterson et al. (2003), Dickman (2010), and Redpath et al. (2013) are more management-oriented, they are referred to in the context of structural conflict analysis. The remaining frameworks that were reviewed demonstrated a theory-oriented approach (Table 2). Two frameworks, namely the conflict intervention triangle and the Levels of Conflicts model presented in Madden and McQuinn (2014) can be considered the most general frameworks that can likely be adapted to any conflict analysis. The remaining frameworks are much more context-specific (Table 2). Those formulated by Shmueli (2008) and Ide (2016) refer to the field of environmental conflicts, the frameworks developed by Dickman (2010) and Patterson et al. (2003) focus on wildlife management, whereas Germain and Floyd’s (1999) and Hellström’s (2001) models concentrate on natural resource conflicts and conflicts in forestry, respectively. Only those developed by Redpath et al. (2013) and White et al. (2009) directly target biodiversity and conservation conflicts, respectively. The majority of the frameworks refer to conflicts that can be understood under the perspective of the constructionist/constructivist paradigm, with some of the earliest frameworks being exceptions (Table 2). Most recently, Ide (2016) referred directly to constructivism in the name of the framework. Finally, some of the frameworks can be applied in quantitative studies (Germain and Floyd 1999; White et al. 2009).

The reviewed frameworks also differed in terms of whether or not they included elements referring to behavioural manifestations of conflicts. Dickman (2010), Ide (2016), and White et al. (2009), in particular, referred directly to stakeholders’ responses, actions, and behaviours, respectively, whereas other authors do not include human actions, at least at the stage of conflict mapping (Table 2, Online Appendix 4).

The majority of the frameworks have interdisciplinary foundations that are best reflected by the number of conflict determinants included (Table 2, Online Appendix 4). Specifically, Hellström (2001) distinguished the social, policy, resource and economic aspects of conflicts, whereas White et al. (2009) distinguished social, ecological and economic factors. Environmental and social risk factors have been delineated by Dickman (2010), but a closer examination reveals that the proposed factors are also of economic or institutional importance. Similarly, whereas Shmueli’s (2008) ‘identity and value frames’ suggest the inclusion of purely sociological content, they include categories, such as ‘economic orientation’, ‘ecological/environmental orientation’ and ‘policy-based decision making’. Shmueli (2008) also addresses psychological determinants and geographical characteristics in a comprehensive manner. In other cases, although geographical settings comprise a crucial assumption of many frameworks (Dickman 2010; Germain and Floyd 1999; Patterson et al. 2003), spatial features are not explicitly referred to within the models. For example, in the framework of Patterson et al. (2003), geographical features must be considered when operationalizing human–wildlife coexistence, however only the latter was named in their model.

The frameworks usually address processual dimensions of conflicts and the necessity for stakeholders to interact (Delli Priscoli 1997; Madden and McQuinn 2014; Walker and Daniels 1997). Some authors propose an approach in which consequences are fed back into a conflict’s initial determinants (Ide 2016; Redpath et al. 2013; White et al. 2009) (Table 2, Online Appendix 4).

Proposed integrated conceptual framework for studying protected area conflicts

Figure 1 shows our proposed integrative framework, comprising four main groups of attributes of PA conflicts (described in detail in Table 1): conflict determinants, conflict dimensions, levels of conflicts, and a group of outcomes of the framework (which are not to be confused with ‘conflict outcomes’, as explained in previous sections and in Table 1). These outcomes, which are all assumed to relate to any conflict situations associated with the existence of a PA, are: conflict issues, conflict interests, and types of conflicts. Conflict determinants (see Table 1), are divided into the following five groups: socio-cultural, institutional, economic, environmental, and psychological. While interactions occur among all of these determinants, those occurring with two groups, namely socio-cultural and psychological determinants are deemed necessary for an investigated phenomenon to qualify as a conflict (assuming that any conflict is of a social nature). We assumed that each of these determinants can be further described with respect to the following three dimensions: substances, processes, and relationships. More specific conflict properties are located at the intersections of conflict determinants and conflict dimensions. New conflict properties that are not specified within a framework, may also emerge as a result of interactions among the determinants. For instance, the conflict property of property rights relating to natural resources within the SES of a PA is shaped by interactions between environmental, economic, and institutional determinants.

A proposed framework for studying protected area conflicts. All the terms used in the framework are described in Table 1

The conflict dimensions of substance and relationships do not require further explanation, while the processual dimension is designed to account only for conflict properties that are temporal in nature. For some of the determinants, we differentiated long-term, medium-term, and short-term sub-dimensions. We refer to long-term sub-dimension when addressing evolutionary changes of the entire group of determinants; the medium-term sub-dimension can be exemplified by a time frame of the political terms of office, while the short-term sub-dimension—by a time frame of a decision-making process for adopting a PA management plan.

Importantly, some but not all of the distinguished properties are expected to have a spatial reference. The association with a geographical space is strongest for environmental determinants, which encompasses their substance-related, process-related (the spatial dynamics of an environment), and relational (interactions among geocomponents) dimensions. However, spatial references can be also captured for other groups of determinants, including institutional (e.g., the spatial scope of PA regulations), socio-cultural (clustering of social norms), or economic (poorer or wealthier municipalities within the SES of a PA).

In line with our geographical approach to conflict analysis, we designed the framework to work at three levels of a spatial scale and at the level of an individual frame (Fig. 1). The regional level describes a general image of conflicts relating to an entire system of PAs in a region. The local level relates to a structure of conflict attributes within a SES of a particular PA and a sub-local level relates to areas of concentration of clashing conflict attributes (in a form of conflictual ‘hotspots’) within this SES. The level of individual frames allows for the inclusion of the conflict orientations of stakeholders engaged in the conflict that are assumed to be the effects of interactions of socio-cultural and psychological values and any other groups of determinants. For example, a stakeholder’s policy-based conflict orientation is modelled as a reinforced interaction of socio-cultural values and psychological emotional dispositions with the group of institutional determinants. The overall individual frame is assumed to include a stakeholder’s risk and situation assessment. Each of these frames can be integrated, or else they may clash at sub-local or local analytical levels, enabling the linking of the individual frame to levels of the spatial scale.

At each analytical level, different outcomes of the conflict components are generated (Fig. 1). Stakeholder-specific conflict interests are formulated at the level of the individual frame. Conflict issues that further shape the conflict interests of the concerned stakeholders (the interests may be connected to the issues or to the conflict’s deeper structure, as perceived by a stakeholder) are formulated at local and sub-local levels. In some cases, conflict interests extend beyond the borders of a particular SES and refer to (supra)regional analytical levels. At the regional level, a PA conflict typology can be constructed based on a generalized collection of various local-level images of conflicts [some specific types of conflicts may entail (supra)regional interests]. The labelling of a PA case study with a certain type of conflict is expected to provide insights into the complexity of conflict determinants and dimensions that shed light on the conflict potential. Further, the potential is modelled as being influenced by a case-study-specific level of understanding of the other frames and interests.

Discussion

Contribution of the proposed framework to state-of-the-art knowledge

The proposed framework for analysing PA conflicts integrates stakeholder-level models for framing a conflict with more general approaches for structuring conflict attributes. Drawing this connection was necessary because some of the reviewed frameworks (Dickman 2010; Patterson et al. 2003) referred to individual and community levels only in their descriptions and not in a structural form. Other authors (Ide 2016; White et al. 2009) did present transitions between the analytical levels, but their structural elaborations differed.Footnote 6 In our framework, linkages between stakeholder and spatial levels were achieved through the inclusion of four conflict levels resulting from a comprehensive review of papers applying different lenses for analysing conflicts to ensure the comparability of structural attributes.

The proposed design of more general analytical levels of conflict was primarily inspired by Hellström (2001), although a number of adjustments to her original proposal were required. First, compared with Hellström’s (2001) framework for analysing forest conflicts, our framework is intended to address the SES of any PA, resulting in the latter framework being potentially more capacious to accommodate possible emerging conflict properties. This is also reflected in the terminology used, which differs across the proposals (e.g., ‘group of environmental determinants’ instead of Hellström’s 2001 ‘resource aspects of conflicts’). Second, we did not follow Hellström’s (2001) approach of distinguishing ‘descriptive aspects of conflicts’ as this led to apparent repetitions of her conflict categories. ‘Approaches to conflict management’ fits well within an institutional group of determinants, whereas ‘types of conflicts’, in our opinion, should be derived from other conflict attributes, which was actually not the case in Hellström’s (2001) proposed framework.Footnote 7 Third, following Madden and McQuinn (2014), we reframed the ‘procedural’ dimension into a ‘processual’ one. The original conception of this dimension should have referred to ‘official or established ways of doing something’ (Madden and McQuinn 2014, p. 102), which was hardly distinguishable from many of the conflict substances. In our opinion, the problem does not exist when the dimension concerns conflict properties that refer to changes over time. Consequently, we did not refer to conflict intensity (ref. Keltner 1987) when describing conflict types. Instead we addressed stages in a conflict development process. A final and key modification was our inclusion of another major component of conflicts (levels of conflicts), which introduced a more geographical perspective. We distinguished three outcomes of the framework (conflict types, conflict issues, and conflict interests). Hellström (2001) mentioned the three conflict attributes but did not propose a method of conjoining them with conflict determinants.

At the level of stakeholders’ individual frames, we referred extensively to Shmueli’s (2008) framing typology, although it was not originally intended to be used for framing conservation conflicts per se. One of the reasons why we selected this approach was because Shmueli (2008) had already applied the typology in the context of a ‘geographical analysis of environmental conflicts’, which facilitated its integration with the spatial levels of our framework. Thus, her ‘process frames’ correspond to the ‘procedural’ dimension of conflict (Madden and McQuinn 2014) and her ‘characterisation frames’ are simply socially constructed attributions (White et al. 2009) that can be viewed as the ‘socio-cultural/relationships’ conflict properties in our framework. However, some of Shmueli’s (2008) frames required restructuring. For instance, we needed to disentangle the list of personal (self) ‘identity and values frames’ that included notions referring to an entire individual frame within our framework (e.g., a complexity or risk assessment; ref. Dickman 2010; Ide 2016), while also including more specific conflict orientations that we interpreted as interactions of the socio-cultural values of a stakeholder and one’s emotional disposition with a certain group of determinants. Specifically, we adopted four different orientations from Shmueli (2008) (Fig. 1) but did not distinguish a scientific orientation. This is because science can contribute to any of the other conflict orientations specified in the framework, reinforcing the knowledge of a stakeholder who is scientifically oriented. Additionally, we focused on organizing components of Shmueli’s (2008) typology into cause-and-effect relationships. For example, we emphasised that Shmueli’s (2008) ‘substance frames’ were derived from other frames, especially ‘identity and values frames’, which was less evident in the original framework developed by Shmueli (2008). Also, some reservations apply to ‘factors influencing frames and their formation’ (see Online Appendix 4). Whereas some of these factors are good examples of conflict determinants, others (e.g., ‘understanding other stakeholders’ interests and positions’) would not apply before the emergence of conflict interests.Footnote 8 Shmueli’s (2008) ‘factors influencing frames and their formation’, especially, ‘needs’, ‘desires’, and ‘fears’ strongly influenced our decision to include the psychological group of determinants within our PA conflict framework. Psychological determinants were often mentioned by authors who had analysed behavioural processes connected with the emergence of conflict (e.g., Dickman 2010; Wieczorek Hudenko 2012), but they were not included into any of the reviewed frameworks.

Towards a consistent typology of protected area conflicts

In our proposed PA conflicts framework, conflict types are presented as regional-level generalisations of different structures of interacting conflict determinants and conflict dimensions that characterise local and sub-local level case studies within a region. This approach responds to popular conservation conflict typologies that distinguish various attributes of conflict rather than pursuing the goal of systemisation. The most frequently cited list of conflict types in recent literature (Redpath et al. 2015c; Sideway 2005; Young et al. 2010) differentiated between conflicts over: values, interests, processes, relationships (inter-personal conflicts), data (including miscommunication and lack of access to data), and facts (structural conflicts). The same list of conflict types was also used by other authors under different labels (see ‘causes of disputes’ in Delli Priscoli 1997). Authors using the typology are aware of the overlapping character of the categories (Young et al. 2010). Specifically, we considered conflicts over facts, processes, and relationships to refer simply to different conflict dimensions (Madden and McQuinn 2014), while conflicts over facts should never be equalled to more deep-rooted structural conflicts that encompasses clash of various conflict determinants. Conflict values precede conflict interests, and as such, should not be juxtaposed (see our interpretation of Shmueli’s 2008 frame categories in “Contribution of the proposed framework to state-of-the-art knowledge” section). Further, conflicts over data, which refer to socio-culturally driven systems of knowledge and processes in which institutional determinants are especially prominent, are the most specific of those included in the list. Whereas we acknowledge that a specific type of PA conflict is associated with conflict interest, it is not the existence of interests per se that makes these conflicts specific, but rather the cross-level character of these interests (Redpath et al. 2013, p. 103). Consistent capturing of such types of conflict is possible only when various levels on a spatial scale are adopted in analytical frameworks such as ours.

Another approach for formulating a conflict typology, proposed by Redpath et al. (2015b), is based on different objectives identified in articles on conflicts in human–wildlife interactions. The authors differentiate the following objectives: conservation, livelihoods, animal welfare, human safety and health, recreation, development and infrastructure, and human well-being. Although some of these objectives overlap, with the last one being sufficiently general to encompass the majority of the others, we still prefer this typology over the one reviewed in the previous paragraph. The typology is based on a comprehensive literature review and adopts a coherent criterion for systematisation. However, this proposal is confined to a human–wildlife setting only.

We also explored the potential for developing a conflict typology that would enable conflicts that are more or less influenced by a geographical context to be identified. Within our framework, such conflict types would result from a structure of conflict categories, in terms of their reference (or not) to a geographical space. It may be possible to present the conflict properties in question in a form that encompasses their spatial clashes (White et al. 2009) as a proxy of a conflict rationalisation process (see Coser 1956). This is a step forward compared to assessing conflict rationality exclusively based on analysis of dispute layers of conflicts. Using the previous approach may at first create an impression of irrationality of a conflict in question, which however tends to change once deep-rooted layers of this conflict are uncovered (Madden and McQuinn 2014).

Consideration of underlying foundations in structural conflict analysis

In light of our critical examination of state-of-the-art conceptual models of conservation-related conflicts and the process of developing our own proposal, we suggest several assumptions that should guide a process of structural conflict analysis in PAs. Differences in the design of a conflict analyses may result in the consideration of varying assumptions and it is important to clarify the theoretical choices made by the authors. From a broad perspective, all five of the proposed assumptions reflect an interdisciplinary approach to conflict analysis with extended geographical conceptual inputs, which we explicated in “Assumption of the spatial character of PA conflicts” section.

The assumption of coverage of only the identification of a conflict

Although a few of the reviewed papers addressed the management (resolution) phases of the conflict analysis process (Dickman 2010; Germain and Floyd 1999; Madden and McQuinn 2014; Patterson et al. 2003; Redpath et al. 2013; Walker and Daniels 1997), we decided to restrict our framework to the identification phase. Redpath et al. (2013) distinguished between the ‘mapping conflict’ and ‘managing conflict’ phases, which also applies to key elements of conflicts proposed by Walker and Daniels (1997). We believe that questions of what (determinants, dimensions, and issues), who (stakeholders and their interests), when and where (processes and setting) asked by Walker and Daniels (1997) should be explicitly addressed by structural conflict analysts. However, their roles relating to questions of how the conflicts are addressed, by whom, and what the outcomes of these actions are should be addressed through an investigation of how these processes in turn affect conflict determinants.

The decision to cover only the identification phase of a conflict analysis process was made based on empirical findings that conflict management methods and their effectiveness are highly context-dependent (Dickman 2010; Hellström 2001; Madden and McQuinn 2014; Manfredo and Dayer 2004). Consequently, encapsulating them within any structural framework is problematic (although roadmaps for managing the process are possible to be designed; Redpath et al. 2013). This decision further reflects current trends in the social sciences and interdisciplinary research. Accordingly, science is no longer expected to provide answers and expert-driven solutions (i.e., decision ends) for social dilemmas; rather it equips stakeholders with scientific inputs into decision-making processes (i.e., decision means) (Bennett et al. 2017; Ozawa 1996; Patterson et al. 2003; Young et al. 2010).

Importantly, our emphasis on conflict identification does not necessitate a static approach to conflict analysis. In our framework, we reflected the dynamic character of conflicts through highlighting the ‘process’ dimension in our framework. Moreover, the interrelation of all of the conflict attributes makes the whole structure highly dynamic. Thus, a change in one conflict factor such as a stakeholder’s economic condition, may induce negative attributions and lead to a conflict’s development (White et al. 2009; see also Keltner 1987). Finally, we find a processual approach strikingly missing in current definitions of conservation conflicts (see Online Appendix 2), which supposedly result from a prolonged omission of conflict temporal dimension in the state-of-the-art frameworks. Thus, we postulate to define a PA conflict as “a social and spatial process that occurs when the interests of two or more parties towards some aspect of a PA existence compete, and when at least one of the parties is perceived to assert its interest at the expense of others” (based on Redpath et al. 2015a, b, c).

Assumption that social (and psychological) components are prerequisites for conflicts

Numerous studies within the conservation conflict literature suggest that the social attributes of conflicts are inseparable from the notion of values (Fulton et al. 1996; Hellström 2001; Madden and McQuinn 2014; Patterson et al. 2003; Shmueli 2008; White et al. 2009). We propose that institutional, economic, and environmental determinants of conflicts are affected by a stakeholder’s valuation process at the level of an individual frame as a result of their inevitable interactions with social and psychological determinants. Consequently, all of the groups of determinants are in fact groups of values that may, however, entail different valuation systems (see e.g., Santos-Martin et al. 2018). For instance, from an idealistic perspective, legal acts (an institutional group of determinants) are codified manifestations of social values relating to the subjects of such acts. Nevertheless, failures occurring in processes relating to the formulation or implementation of policies can result in clashes between a final binding regulation and an initial set of values (Hellström 2001). Further, policies can never fully address the complexities of societal values. Consequently, whereas formal legitimation of PAs, as public institutions, is strongly established, their de facto legitimation can be simultaneously weak, inducing social conflicts.

Similarly, whereas the notion of values can be associated with economic or environmental determinants, perspectives regarding such values may vary. For example, environmental economists tend to express the economic values of natural resources in monetary terms (Gómez-Baggethun et al. 2010). By contrast, some environmentalists argue that species and habitats have intrinsic values that are not dependent on humans (see Dietz et al. 2005). Such differences ultimately stem from the values as framed in the cognitive hierarchy theory (psychological group of determinants) which defines values as “stable mental constructs that transcend specific situations and represent people’s basic needs, which may vary among groups” (Estévez et al. 2014, p. 22).

Last, our framework distinguishes between psychological and social determinants. Authors from various disciplines claim that conflicts in general (Coser 1956) and human decision-making processes in particular (Hipel and Walker 2011; Kahneman 2003; Levy et al. 2009; Sloman 1996) entail two fundamental elements: the rational and the emotional. Both elements can be described at the level of an individual’s psychological processes, which we found missing in the state-of-the-art conservation conflict frameworks.

Assumption of a focus on non-behavioural expressions of PA conflicts

As this review shows, ‘behaviours’, ‘responses to conflicts’, or ‘behaviours’ are elements of a number of the frameworks proposed within the field of conservation, biodiversity, or HWCs (Dickman 2010; Fulton et al. 1996; Ide 2016; White et al. 2009). However, the cited authors generally acknowledge that relationships between these attributes and underlying conflict determinants are not obvious (e.g., White et al. 2009, p. 246). In our opinion, these authors might have overlooked the fact that components of structural conflict and those of human behaviours address different levels of analyses. This problem does not apply to Ajzen’s (1991) theory of planned behaviour, which is often referenced by theorists of conservation conflict. Ajzen (1991) did distinguish attitudes and norms (together with perceived behavioural control) among the prerequisites of behaviour. However the theory refers only to personal attitudes towards the behaviour, which is much more specific than the majority of general community-level attitudes arising during conflictual situations. Similarly, Ajzen’s (1991) norms are closer to personal ‘evaluation based on [one’s] beliefs about the expectations of others’ (see interpretation of the term by Manfredo and Dayer 2004, p. 318) than to a socially-determined conflict property. Considering the abovementioned point, while acknowledging the complexity of human decision-making processes (Wieczorek Hudenko 2012) and the highly context-dependent nature of the behavioural manifestation of conflicts (Hellström 2001), we decided not to include the behavioural stages within our framework. This issue has been well-described by Dickman (2010) who pointed out that managers’ focus on instances of intense conflict is bound to result in the escalation of such processes elsewhere where conflict structures are similar but latent. At the same time, we acknowledge the existence of negative feedback loops between conflict behaviours and conflict determinants (Ide 2016; White et al. 2009).

A constructionist/constructivist perspective relating to protected area conflicts

A study of PA conflicts entails an analysis of frames or images (see Table 1) of actually existing conflicts as constructed by the concerned stakeholders (Hannigan 1995; Hellström 2001; Ide 2016; Litmanen 1996). Our assumption is necessarily derived from all three of the above described assumptions. For example, a discussion on any form of perceptions would not be possible without highlighting the role of social or psychological conflict determinants. This approach contrasts with those derived from positivistic social sciences, which require the existence of several objective and general rules governing people’s actions (Rosenberg 2008).

Ide (2016) clearly illustrated the multi-layered character of conflict frames or images.Footnote 9 He depicted the ‘material quality of the world’ as an objective element of the framework that is external to constructed, group-based conflict frames/images. Dickman (2010) also distinguished real and perceived components of conflicts (specifically, conflict-related costs). According to our constructionist/constructivist perspective, complete recognition of the ‘objective’ properties is never achieved. However, we do not deny the role of positivist approaches in interdisciplinary conflict analysis (White et al. 2009). These approaches can be especially useful for the purposes of monetary accounting of natural resources in PAs (a group of economic determinants), assessments of the ecological significance of these resources (a group of environmental determinants), and content analysis of legal acts on nature protection (a group of institutional determinants). However, it is important that the results of such inquiries remain open for further modifications based on the influence of the social and psychological attributes of conflicts.

A constructionist/constructivist approach to PA conflict analysis has consequences for how PAs are interpreted in a geographical sense. Specifically, spatial analysis necessitates a SES approach (Palomo et al. 2013, 2014) to enable analyses not only within a PA’s administrative borders but also in a zone of mutual interdependence of the protected environment and local societies. Importantly, the external boundaries of such SES will remain blurred and will never be precisely delineated.

Last, when adopting the constructionist/constructivist assumption, a researcher should be aware of several constraints that would inevitably be faced during the research process. These include the superficial character of respondents’ conflict-related statements (Madden and McQuinn 2014; Shmueli 2008; Sites 1990), especially if contact between the researcher and respondent occurs just once; biases in respondents’ statements that stem from reflexiveness of the research process (Rosenberg 2008); and a researcher’s biases during the stage of data interpretation, which will never be free from the researchers’ own social constructions of the phenomena under investigation (Hellström 2001).

Assumption of the spatial character of PA conflicts

The spatial assumption highlights the role of geography in PA conflict analysis. It is reflected in the selected analytical setting (PAs as spatial entities), in the cross-level character of the framework along the spatial scale and in the role of the spatial aspect of conflict attributes in conflict analysis. The ‘spatial’ assumption does not contradict the ‘social’ assumption; rather the two are closely interrelated. As Patterson et al. (2003) have shown in their model, the stakeholders’ belief systems often entail some spatial consequences: for example, supporters of animal rights would prefer ‘spatial’ coexistence with wildlife, whereas hunters may prefer a higher degree of separation between ‘wild’ and ‘settled’ areas. Further, the ways in which stakeholders construct a conflict situation may shape the perceived boundaries of their localities (Litmanen 1996). Conversely, spatial processes entail certain changes in values, which may reflect changes in perspectives towards modified land, or inputs of new values ascribed to a certain place by those moving into this area (Brown and Weber 2012; Patterson et al. 2003).

Through the adoption of a multi-level approach to PA conflict analysis, the framework retains analytical separateness when addressing any of the spatial levels. Moreover, it enables conflict types resulting from clashing interests of a cross-level character to be captured (Redpath et al. 2013). Such a structure of interests is possible because many properties of conflict do not apply at local levels, especially in cases of deeply-rooted conflicts (Madden and McQuinn 2014). For instance, legislation relating to the majority of national parks is a national-level determinant, even though it ultimately concerns a particular, local-level spatial entity (see Linnell and Boitani 2012). Most theoretical approaches used to address such conditions [e.g., the distance-decay factor (Shmueli 2008), the not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) syndrome (Armour 1984,) or locally unwanted land usage (LULU) (Freudenburg and Pastor 1992); see Litmanen 1996 for a brief review] describe the problem as one of polarization between two parties, which entails excessive simplification. Consequently, it was necessary to propose a solution that enables incorporation of the simplified approaches (e.g., NIMBY or LULU) into a broader PA conflict framework.

A final point relating to the spatial character of PA conflicts concerns the problem of resource scarcity, which has been addressed by scientists across many disciplines (Coser 1956; Hardin 1968; Hipel and Walker 2011; Kelso 1963). In our framework, this problem is differently interpreted at various analytical levels. At a regional level, scarcity of valued nature results in a certain spatial distribution of PAs, which, in turn, results in the clustering of potential PA conflicts across the region. At a local level, the entire PA is interpreted as a scarce resource that needs to fulfil a variety of potential functions (Dudley and Stolton 2008). Last, at a sub-local level, place-specific resources located within these PAs (e.g., climbing zones in mountainous national parks) may be too scarce (or too legally restricted) to satisfy the interests of all the stakeholders. Of the reviewed frameworks, those formulated by Floyd (1993) and Germain and Floyd (1999) directly addressed this issue.

Potential applications of the proposed framework

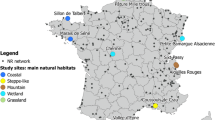

The framework enables the performance of empirical research in settings where PAs are the central arenas of conservation conflicts. Such settings exist, for example, in Europe, where the implementation of the European Ecological Network—Natura 2000 PA system has met with opposition in practically all of the EU Member States (Blicharska et al. 2016). The conflicts emerged within Natura 2000 sites (Grodzinska-Jurczak and Cent 2011; Hiedanpää 2002; Ledoux et al. 2000; Young et al. 2007) despite the aim of aligning the Natura 2000 approach with the concept of sustainable development (European Commission 1992), thus the one which in principle does not follow ‘isolative’ paradigms in nature conservation (Colchester 1994). Moreover, as noted by Linnell et al. (2015) and Trouwborst et al. (2017), European conservation is characterised by an enduring tradition of interconnection between nature and culture (Boitani and Sutherland 2015), the human–wildlife coexistence paradigm (Chapron et al. 2014) and conservation policy aimed at achieving a balance among different value systems, including cultural and socio-economic ones. This approach has generated spatial challenges for the implementation of more dichotomist ideas, such as ‘rewilding’ nature that are also expanding in Europe (Linnell et al. 2015).

However, our framework is expected to be applicable not only to settings at a continental scale, such as Natura 2000 but also to national parks, regional or local nature reserves and other forms of spatially designated nature protection. By addressing gaps at a conceptual level, the proposed framework contributes to more comprehensive empirical inquiries by extending the scope of interests beyond the most ‘strict’ or larger types of PAs (Jones et al. 2017).

Our framework can also contribute to resolving spatial problems in human–wildlife interactions, considering, for example, socio-ecological boundaries between PAs and intensively managed areas, which are easily crossed by wild animals (Bautista et al. 2017). Other issues relate to challenges connected with permanent and inflexible PA borders, hindering attempts to address current and dynamic environmental problems, such as climate change and resulting changes in the geographical locations of habitats and species. This problem becomes intensified during processes of PA designation or expansion (Hausner et al. 2015; Niedziałkowski et al. 2012), when the blurred boundaries of socio-ecological phenomena are replaced with sharp borders, especially when compliance with an existing land property structure is required (Kamal et al. 2015a, b). All of these issues tend to result in conflicts that can be described and analysed through the application of our framework.

Notes

Scholars use different terms for conceptual frameworks presented in a form of graphical models. In addition to ‘conceptual frameworks’ and ‘models’, they refer to ‘analytical frames’, ‘generic/theoretical frameworks’ and ‘roadmaps’.

Although the ontological/epistemological concepts of constructionism and constructivism are similar, in the former, social phenomena are constructed through a process of interaction of social discourses, whereas the latter places more emphasis on personal constructions of perceived reality (Young and Collin 2004). In practice, both processes are necessary in a context of protected area conflicts (evidenced in the use of, respectively, ‘discourses’ and ‘individual frames’ in the reviewed papers). We therefore refer to both terms.

Walker and Daniels (1997) list the central elements of conflict situations. Most of these elements evidence classic structural characteristics (perceived incompatibility, interests, goals, aspirations, two or more interdependent parties, interaction, and communication). However three of them are connected with conflict management processes (bargaining/negotiation, strategy/strategic behaviour, and incentives to cooperate and compete).

The term ‘human–wildlife impacts’ does not entail people’s positions regarding the impacts (Redpath et al. 2015b).

White et al. (2009) introduced conflict factors from a general perspective, assigning the resultant attitudinal, behavioural, and outcome indicators to particular conflict actors. At the same time, the authors emphasised that the ‘attitudes-behaviour-outcomes’ component of a model represented ‘complex relationships that, so far, are largely undefined’ (p. 246). By contrast, Ide (2016) initiated the framework with group-level processes (discourses, situation assessments, identities, interests, and actions) and concluded with inter-group-level conflicts.

Hellström (2001) depicted two-side relationships among societal and descriptive aspects of conflicts in her framework. However, these relationships were hardly addressed in her subsequent structural conflict analysis.

Ide (2016) suggests that conflict interests arise as a consequence of many preceding conflict attributes.

References

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behaviour. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50:179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Al-Mutairi MS, Hipel KW, Kamel MS (2008) Fuzzy preferences in conflicts. J Syst Sci Syst Eng 17:257–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11518-008-5088-4

Armour A (1984) The not-in-my-backyard syndrome. In: Proceedings of a symposium on public involvement in siting waste management facilities. Faculty of Environmental Studies, York University, Downsview

Bautista C et al (2017) Patterns and correlates of claims for brown bear damage on a continental scale. J Appl Ecol 54:282–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12708

Baynham-Herd Z, Redpath S, Bunnefeld N, Molony T, Keane A (2018) Conservation conflicts: behavioural threats, frames, and intervention recommendations. Biol Conserv 222:180–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.04.012

Bennett NJ et al (2017) Mainstreaming the social sciences in conservation. Conserv Biol 31:56–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12788

Berkes F (2004) Rethinking community-based conservation. Conserv Biol 18:621–630. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.00077.x

Blicharska M, Orlikowska EH, Roberge J-M, Grodzinska-Jurczak M (2016) Contribution of social science to large scale biodiversity conservation: a review of research about the Natura 2000 Network. Biol Conserv 199:110–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.05.007

Boitani L, Sutherland WJ (2015) Conservation in Europe as a model for emerging conservation issues globally. Introduction. Conserv Biol 29:975–977. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12530

Brown G, Weber D (2012) Measuring change in place values using public participation GIS (PPGIS). Appl Geogr 34:316–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2011.12.007

Butchart SHM et al (2015) Shortfalls and solutions for meeting national and global conservation area targets. Conserv Lett 8:329–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12158

Cash DW et al (2006) Scale and cross-scale dynamics: governance and information in a multilevel world. Ecol Soc 11(2):8

Castro A et al (2015) Do protected areas networks ensure the supply of ecosystem services? Spatial patterns of two nature reserve systems in semi-arid Spain. Appl Geogr 60:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2015.02.012

CBD (2010) The strategic plan for biodiversity 2011–2020 and the Aichi biodiversity targets. In: Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity. https://www.cbd.int/decision/cop/?id=12268. Accessed 1 Sep 2018

Chapron G et al (2014) Recovery of large carnivores in Europe’s modern human-dominated landscapes. Science 346:1517–1519. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1257553

CICR (2000) Becoming a third-party neutral: resource guide. Canadian Institute for Conflict Resolution, Ridgewood Foundation for Community-Based Conflict Resolution, Ottawa

Colchester M (1994) Salvaging nature: indigenous peoples, protected areas and biodiversity conservation. United Nation Research Institute for Social Development, Geneva

Conover MR (2002) Resolving human–wildlife conflicts: the science of wildlife damage management. Lewis Publishers, CRC Press, Boca Raton

Coser LA (1956) The functions of social conflict. The Free Press, New York

Cumming GS (2016) The relevance and resilience of protected areas in the Anthropocene. Anthropocene 13:46–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ancene.2016.03.003

Cumming GS (2018) A review of social dilemmas and social–ecological traps in conservation and natural resource management. Conserv Lett 11:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12376

Cumming GS et al (2015) Understanding protected area resilience: a multi-scale, social–ecological approach. Ecol Appl 25:299–319. https://doi.org/10.1890/13-2113.1

De Pourcq K, Thomas E, Arts B, Vranckx A, Léon-Sicard T, Van Damme P (2017) Understanding and resolving conflict between local communities and conservation authorities in Colombia. World Dev 93:125–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.12.026

Delli Priscoli J (1997) Participation and conflict management in natural resources decision-making. In: Solberg B, Miina S (eds) Conflict management and public participation in land management. European Forest Institute, Joensuu, pp 61–87

Deutsch M (1973) The resolution of conflict. Yale University Press, New Haven

Di Marco M, Butchart SHM, Visconti P, Buchanan GM, Ficetola GF, Rondinini C (2016) Synergies and trade-offs in achieving global biodiversity targets. Conserv Biol 30:189–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12559

Dickman AJ (2010) Complexities of conflict: the importance of considering social factors for effectively resolving human–wildlife conflict. Anim Conserv 13:458–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1795.2010.00368.x

Dietz T, Fitzgerald A, Shwom R (2005) Environmental values. Annu Rev Environ Resour 30:335–372. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.energy.30.050504.144444

Dudley N (2008) Guidelines for applying protected area management categories. IUCN, Gland

Dudley N, Stolton S (2008) Defining protected areas: an international conference in Almeria, Spain. IUCN, Gland

Dudley N et al (2010) Natural solutions: protected areas helping people cope with climate change. IUCN/WCPA, TNC, UNDP, WCS, The World Bank and WWF, Gland

Estévez RA, Anderson CB, Pizarro JC, Burgman MA (2014) Clarifying values, risk perceptions, and attitudes to resolve or avoid social conflicts in invasive species management. Conserv Biol 29(1):19–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12359

European Commission (1992) Council Directive May 1992 on the Conservation of Natural Habitats and of Wild Fauna and Flora. European Commission. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CONSLEG:1992L0043:20070101:EN:PDF. Accessed 1 Sep 2018

European Parliament (2012) European Parliament resolution of 20 April 2012 on our life insurance, our natural capital: an EU biodiversity strategy to 2020. European Parliament. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//NONSGML+TA+P7-TA-2012-0146+0+DOC+PDF+V0//EN. Accessed 1 Sep 2018

FAO (1998) Integrated coastal area management and agriculture, forestry and fisheries. FAO Guidelines. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome

Floyd DW (1993) Managing rangeland resources conflicts. Rangelands 15:27–30

Freeman R (1984) Strategic management: a stakeholder approach. Basic Books, New York

Freudenburg WR, Pastor SK (1992) NIMBYs and LULUs: stalking the syndromes. J Soc Issues 48:39–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1992.tb01944.x

Fulton DC, Manfredo MJ, Lipscomb J (1996) Wildlife value orientations: a conceptual and measurement approach. Hum Dimens Wildl 1:24–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209609359060

García-Llorente M et al (2018) What can conservation strategies learn from the ecosystem services approach? Insights from ecosystem assessments in two Spanish protected areas. Biodivers Conserv. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-016-1152-4

Geldmann J, Barnes M, Coad L, Craigie ID, Hockings M, Burgess ND (2013) Effectiveness of terrestrial protected areas in reducing habitat loss and population declines. Biol Conserv 161:230–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2013.02.018

Germain RH, Floyd DW (1999) Developing resource-based social conflict models for assessing the utility of negotiation in conflict resolution. For Sci 45:394–406. https://doi.org/10.1093/forestscience/45.3.394

Gómez-Baggethun E, de Groot R, Lomas PL, Montes C (2010) The history of ecosystem services in economic theory and practice: from early notions to markets and payment schemes. Ecol Econ 69:1209–1218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.11.007

Grodzinska-Jurczak M, Cent J (2011) Expansion of nature conservation areas: problems with Natura 2000 implementation in Poland? Environ Manag 47:11–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-010-9583-2

Guerrero AM, McAllister RRJ, Wilson KA (2015) Achieving cross-scale collaboration for large scale conservation initiatives. Conserv Lett 8:107–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12112

Hannigan JA (1995) Environmental sociology. A social constructionist perspective. Routledge, London

Hardin G (1968) Tragedy of the commons. Science 162:1243–1248. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.162.3859.1243

Hausner VH, Brown G, Lægreid E (2015) Effects of land tenure and protected areas on ecosystem services and land use preferences in Norway. Land Use Policy 49:446–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.08.018

Hellström E (2001) Conflict cultures—qualitative comparative analysis of environmental conflicts in forestry. Silva Fennica monographs, vol 2. The Finnish Society of Forest Science. The Finnish Forest Research Institute

Hiedanpää J (2002) European-wide conservation versus local well-being: the reception of the Natura 2000 Reserve Network in Karvia, SW-Finland. Landsc Urban Plan 62:113–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2046(02)00106-8

Hipel KW, Walker SB (2011) Conflict analysis in environmental management. Environmetrics 22:279–293. https://doi.org/10.1002/env.1048

Hummel C et al (2019) Protected Area management: fusion and confusion with the ecosystem services approach. Sci Total Environ 651(2):2432–2443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.033

Ide T (2016) Toward a constructivist understanding of socio-environmental conflicts. Civ Wars 18:69–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698249.2016.1144496

IUCN (2012) The role of protected areas in regard to climate change. Scoping study. IUCN, Georgia

Jones N, McGinlay J, Dimitrakopoulos PG (2017) Improving social impact assessment of protected areas: a review of the literature and directions for future research. Environ Impact Assess Rev 64:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2016.12.007

Kahneman D (2003) A perspective on judgment and choice: mapping bounded rationality. Am Psychol 58:697–720. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.58.9.697

Kamal S, Grodzinska-Jurczak M, Pietrzyk-Kaszynska A (2015a) Challenges and opportunities in biodiversity conservation on private land: an institutional perspective from Central Europe and North America. Biodivers Conserv 24:1271–1292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-014-0857-5

Kamal S, Grodzińska-Jurczak M, Brown G (2015b) Conservation on private land: a review of global strategies with a proposed classification system. J Environ Plan Manag 58:576–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2013.875463

Kareiva P, Marvier M (2012) What is conservation science? BioScience 62(11):962–969. https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2012.62.11.5

Kelso MM (1963) Resolving land use conflicts. In: Ottoson HW (ed) Land use policy and problems in the United States. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln

Keltner JW (1987) Mediation: toward a civilized system of dispute resolution. Speech Communication Association, Annandale

Kovács E, Fabók V, Kalóczkai Á, Hansen HP (2016) Towards understanding and resolving the conflict related to the Eastern Imperial Eagle (Aquila heliaca) conservation with participatory management planning. Land Use Policy 54:158–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.02.011

Lecy JD, Beatty KE (2012) Representative literature reviews using constrained snowball sampling and citation network analysis. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1992601

Ledoux L, Crooks S, Jordan A, Kerry Turner R (2000) Implementing EU biodiversity policy: UK experiences. Land Use Policy 17:257–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-8377(00)00031-4

Leopold A (1933) Game management. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York

Leung W, Noble B, Gunn J, Jaeger JAG (2015) A review of uncertainty research in impact assessment. Environ Impact Assess Rev 50:116–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2014.09.005

Levy JK, Hipel KW, Howard N (2009) Advances in drama theory for managing global hazards and disasters. Part I: theoretical foundation. Group Decis Negot 18:303–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10726-008-9145-7

Lincoln WF (1986) The course in collaborative negotiations. National Centre Associates, Inc., Tacoma

Linnell JDC, Boitani L (2012) Building biological realism into wolf management policy: the development of the population approach in Europe. Hystrix Ital J Mammal 23:80–91. https://doi.org/10.4404/hystrix-23.1-4676

Linnell JDC, Kaczensky P, Wotschikowsky U, Lescureux N, Boitani L (2015) Framing the relationship between people and nature in the context of European conservation. Conserv Biol 29:978–985. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12534

Litmanen T (1996) Environmental conflict as a social construction: nuclear waste conflicts in Finland. Soc Nat Resour 9:523–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941929609380991

Liu J, Ouyang Z, Miao H (2010) Environmental attitudes of stakeholders and their perceptions regarding protected area-community conflicts: a case study in China. J Environ Manag 91:2254–2262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.06.007

Mace GM (2014) Whose conservation? Science 345:1558–1560. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1254704

Madden F (2004) Creating coexistence between humans and wildlife: global perspectives on local efforts to address human–wildlife conflict. Hum Dimens Wildl 9:247–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871200490505675

Madden F, McQuinn B (2014) Conservation’s blind spot: the case for conflict transformation in wildlife conservation. Biol Conserv 178:97–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.07.015

Maes J, Paracchini ML, Zulian G, Dunbar MB, Alkemade R (2012) Synergies and trade-offs between ecosystem service supply, biodiversity, and habitat conservation status in Europe. Biol Conserv 155:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2012.06.016

Manfredo MJ, Dayer AA (2004) Concepts for exploring the social aspects of human–wildlife conflict in a global context. Hum Dimens Wildl 9:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871200490505765

Martin A, Coolsaet B, Corbera E, Dawson NM, Fraser JA, Lehmann I, Rodriguez I (2016) Justice and conservation: the need to incorporate recognition. Biol Conserv 197:254–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.03.021

Martín-López B, Gómez-Baggethun E, García-Llorente M, Montes C (2014) Trade-offs across value-domains in ecosystem services assessment. Ecol Indic 37:220–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.03.003

Moore CW (1986) The mediation process. Practical strategies for resolving conflict. Wiley, New York

Mouchet MA, Paracchini ML, Schulp CJE, Stürck J, Verkerk PJ, Verburg PH, Lavorel S (2017) Bundles of ecosystem (dis)services and multifunctionality across European landscapes. Ecol Indic 73:23–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.09.026

Newig J, Fritsch O (2009) Environmental governance: participatory, multi-level—and effective? Environ Policy Gov 19:197–214. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.509

Niedziałkowski K, Paavola J, Jędrzejewska B (2012) Governance of biodiversity in Poland before and after the accession to the EU: the tale of two roads. Environ Conserv 40:108–118. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892912000288

Nogueira EM, Yanai A, de Vasconcelos SS, de Alencastro Graça PML, Fearnside PM (2018) Brazil’s Amazonian protected areas as a bulwark against regional climate change. Reg Environ Change 18:573–579. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-017-1209-2

Ozawa CP (1996) Science in environmental conflicts. Sociol Perspect 39:219–230. https://doi.org/10.2307/1389309

Palomo I, Martín-López B, Potschin M, Haines-Young R, Montes C (2013) National parks, buffer zones and surrounding lands: mapping ecosystem service flows. Ecosyst Serv 4:104–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2012.09.001

Palomo I, Montes C, Martin-Lopez B, Gonzalez JA, Garcia-Llorente M, Alcorlo P, Mora MRG (2014) Incorporating the social–ecological approach in protected areas in the Anthropocene. Bioscience 64:181–191. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/bit033

Pascual U et al (2017) Valuing nature’s contributions to people: the IPBES approach. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 26–27:7–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2016.12.006