Abstract

The Nagoya Protocol for access and benefit sharing (ABS) attaches significance to India since the country exchanges classical biological control agents to manage invasive alien species. Classical biological control differs from commercial biological control in that it involves the use of co-evolved, host specific natural enemies from the host’s native region to control the host wherever invasive. The national Biological Diversity Act is responsible for implementing ABS in India. It stipulates the means for use of biological resources for various purposes including research and commerce. However, commercial use of bioresources as biological control agents is not included. ABS regulates the exchange of research results using biological resources and related intellectual property rights. India is yet to implement the Nagoya Protocol effectively due to certain gaps in the Biological Diversity Act concerning some of the key provisions in the protocol that need to be addressed. However, some examples of the application of ABS measures for export of biological resources are discussed here. For export of biological control agents from India, collaborative research with the recipient country is necessary and is governed by the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare. Multiplication of biological control agents for commercial use and release is governed by ABS regulations. For importation of biological control agents into India, the exporting country regulations apply, and the Plant Protection Advisor grants permission. To implement the Nagoya Protocol effectively in India, we recommend that: (1) user country policies include clauses that discourage misuse of biological resources, (2) the consent of local communities be sought before accessing biological resources instead of just ‘consulting’ them, (3) ABS provisions are clearly stated, including what is covered and what is not covered under the Biological Diversity Act, (4) ABS provisions be made more flexible to facilitate compliance, and (5) the roles and responsibilities of each agency involved in ABS implementation be clearly defined.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

India has a long history of introducing biological control agents to manage invasive alien species (IAS) (Sankaran 1973; Singh 2001). Most of these introductions have mainly been parasitoids or predators to manage invasive alien insect pests or phytophagous arthropods to manage invasive alien plants. Although several plant pathogens have been introduced world-wide to manage invasive alien plants, Puccinia spegazzinii de Toni (Pucciniaceae) was the first plant pathogen to be introduced into India to manage an invasive weed, Mikania micrantha Kunth (Asteraceae) (Sankaran et al. 2008; Sankaran and Suresh 2013; Winston et al. 2014).

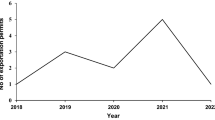

The first recorded case of a ‘classical’ biological control in India was fortuitous since a scale insect Dactylopius ceylonicus Costa (Hemiptera: Dactylopiidae) introduced from Brazil in 1795 to produce cochineal dye also controlled the spread of the invasive drooping prickly pear, Opuntia monocantha Haworth (Cactaceae) (Tryon 1910; Goeden 1978). However, since then, over 35 classical biological control (CBC) agents have been introduced into India to mitigate the threats of invasive plants alone (Winston et al. 2014). Table 1 provides a list of CBC agents imported by India during 2002–2021. Puccinia komarovii var. glanduliferae Tanner, Ellison, Kiss &Evans (Pucciniaceae) collected from parts of the Himalayas in India to manage the weed Impatiens glandulifera Royle (Balsaminaceae), widespread in the UK, was the only CBC agent exported from India during this period (Ellison et al. 2020).

In view of this long history, and current activity of India in classical biological control, the opportunities and constraints related to the exchange of biological control agents under access and benefit sharing (ABS) measures envisaged under the Nagoya Protocol assumes great relevance for the country. The Nagoya Protocol, an international agreement to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), aiming at conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, provides a legal framework to ensure the fair and equitable sharing of benefits emerging from utilization of genetic resources world-wide (CBD 2011, 2022a). The protocol came into force on 12 October 2014.

Access and benefit sharing—international regulations

In Article 8 (h), the CBD recognized the threats posed by IAS and requested contracting parties to prevent the introduction or eradicate and control alien species which pose a threat to the environment, ecology, and biodiversity (https://www.cbd.int/idb/2009/about/cbd/). The Nagoya Protocol includes ABS when a natural enemy of a species is transferred from its native country to a non-native country for classical biological control of an invasive alien species. The benefits of classical biological control over other methods of control are its high specificity, cost effectiveness, self-sustainability, and long-term efficacy in managing invasive alien species (Heimpel and Mills 2017). The ABS mandates to identify and remunerate all those who have played a key role in conserving genetic resources and hence have a claim for the benefits they accrue (Pisupathi 2015). In the case of classical biological control non-monetary benefits (e.g., assistance to build capacity in provider countries, train personnel, build scientific partnerships) have been provided (Cock et al. 2010; Mason et al. 2023).

ABS is connected to the user and the provider nations through the main concepts of Prior Informed Consent (PIC) and Mutually Agreed Terms (MAT). The PIC is the prior permission accorded by the provider nation to the user for accessing the genetic resources. This usually conforms to the prescribed national legislation and institutional mechanism of the provider. The MAT is the arrangement between the provider and the user of the genetic resources on the terms of access of their use and sharing of benefits derived (CBD 2022a). Recognizing the importance of sharing benefits, the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (CGRFA) under the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) developed an international agreement, the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA), that included a concept of farmer's rights in recognition of their contribution to conserve plant genetic resources for food and agriculture (PGRFA) (ITPGRFA 2022).

The ITPGRFA deals only with ABS issues related to PGRFA while the Nagoya Protocol focuses on ABS of genetic resources in general, including biological control agents. The obligations under both these instruments and their mode of implementation at both national and international levels have been discussed by Garforth and Frison (2007), Claudio (2008), Nijar (2011), and Cabrera et al. (2013).

According to Halewood et al. (2013), the Nagoya Protocol includes proposals for countries to regulate access to their sovereign genetic resources through bilateral ABS agreements, while the ITPGRFA assists international gathering and allocation of resources for agricultural research and food security reciprocally. In effect, ABS arising from PGRFA attached to the Nagoya Protocol and ITPGRFA are different which makes coactive implementation of both a challenge for countries. In this situation, countries such as India, who are parties to CBD, the Nagoya Protocol and ITPGRFA, may have to develop suitable regulations to enact ABS to fulfil the requirements under ITPGRFA while safeguarding their sovereign rights on the genetic resources under the protocol.

The Nagoya Protocol was adopted as a binding legal instrument to enable access and benefit sharing since the Bonn Guidelines adopted by CBD in 2002 (intended to assist governments for adopting measures to govern ABS in their countries) had certain inadequacies in implementing ABS (Brahmi et al. 2021). The Nagoya Protocol implies that benefit sharing includes access to genetic resources, transfer of pertinent technologies and adequate funding (IEEP, Ecologic and GHK 2012). Therefore, benefit sharing includes more than apportioning a part of the proceeds when products are developed using genetic resources (Thomas et al. 2012). Also, the Nagoya Protocol specifies that the provisions for benefit sharing may be mutually developed between the provider and the user of the genetic resource based on an agreement involving MAT. The Nagoya Protocol has an ABS Clearing House (ABSCH) on its website for exchange of information on ABS and serves as a main tool to enable enactment of the protocol. All countries in favour of access to genetic resources are required to upload their agreements on this website. Also, procedures on how to access genetic resources from individual countries are uploaded on the ABSCH for information and use by researchers/and entrepreneurs (CBD 2022b).

When the Nagoya Protocol came into force in October 2014, the member nations were required to rationalize the implementation of ABS as the protocol provides only a general framework. Further, to provide directions on the execution of the protocol, the CBD established a Group of Legal and Technical Experts on Concepts, Terms, Working Definitions and Sectoral Approaches (CBD 2008). Although the Group indicated the impartiality of CBD concerning different groups of genetic resources or different areas, there are some basic differences in these that help the development of the regulations, namely type of application or target use (commercial or non-commercial, food and agriculture, biological control, pharmacological, etc.) and the type of genetic resources or their location (e.g., higher plants, microorganisms; marine, terrestrial, ex situ, in situ) (Tvedt 2014). ABS, through a bilateral contract between the supplier and recipient of the biological resources, calls for developing customised provisions for ABS to suit both the provider and the user.

Implementing ABS provisions under the Nagoya Protocol: the biological diversity act of India

The government of India enacted the Biological Diversity Act (BDA) in 2002, to comply with the objectives of the CBD (National Biodiversity Authority 2022a). The Act has the objective of conservation and sustainable use of India’s biological diversity and includes provisions for ABS, modalities of which were proposed later by Nagoya Protocol. The implementation of the BDA is through a decentralized three-tier system that includes the National Biodiversity Authority (NBA), the State Biodiversity Boards (SBBs) and the local level Biodiversity Management Committees (BMCs) (Fig. 1).

Sections 3, 4, 6, 7 and 21 in the BDA deal with ABS and its regulatory requirements. The sections stipulate that the bio-resources and related knowledge can be used for survey, utilization, research and commercial purposes. Section 2 (f) of the BDA identifies commercial utilization of biological resources such as medicines, industrial enzymes, food flavours, perfumes, cosmetics, colours, extracts and genes used for improvement of crops and livestock through genetic interventions. However, traditional practices or conventional breeding used in agriculture and animal husbandry and commercial use of a biological resource as a biological control agent were not included in the BDA. The BDA defines who can and cannot access biological resources or associated knowledge for various purposes in the country (under Sect. 3 of the Act) (National Biodiversity Authority 2022b, c). Further, the ABS regulations under the BDA are also expected to address transfer of research results based on biological resources originated in or obtained from India (National Biodiversity Authority 2022b, c). It also covers Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) for any innovative work or product based on information or research emanating from any bio-resource from India (National Biodiversity Authority 2022b, c).

The Patent Act in India specifically requires applicants to reveal the source of the material if a biological resource is used for any work included in the application. Section 6 of the BDA stipulates prior approval of NBA when a biological resource from India is used in inventions/research. The approval needs to be cited in patent applications filed in India or abroad. Rule 18 of the Biological Diversity Rules discusses how approval for protection of intellectual property may be sought from the NBA. Also, explicit guidelines on the procedures for approval of patents using Indian biological resources are issued by the Controller General of Patent and Trademarks, India.

The BDA approves ABS based on information provided in Forms I to IV wherein Form I is used to decide access approval to biological resources and associated traditional knowledge. Form II is used to request prior approval of NBA for sharing the results of research with foreign nationals/companies/non-resident Indians and for commercial uses. Form III is to request prior approval of the NBA to apply for patents. Form IV is used to appeal approval of NBA for transfer of the accessed biological resources and related traditional knowledge to a third party (National Biodiversity Authority 2022c, d).

All issues concerning ABS including the crop germplasm included under the ITPGRFA (Annex I) were within the mandate of BDA until 2014. As the BDA created hurdles to realize the national commitments provided in the ITPGRFA, the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare was made the nodal agency to implement the ITPGRFA in place of BDA. The Ministry cooperates with the NBA to implement ABS agendas (Cabrera et al. 2013).

Challenges to implement Nagoya Protocol on ABS at the national level

India ratified the Nagoya Protocol in October 2012, but its effective implementation is still pending. The BDA under the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change is responsible for implementation of the protocol. However, there are several gaps in the BDA regarding certain key provisions of the Nagoya Protocol that precludes its effective implementation. The gaps include: (1) a lack of user country mechanism for implementation of ABS provisions (Article 15); (2) non-description of checkpoints to ensure whether all provisions of the benefits have been honoured (Article 17); and (3) a lack of guidelines to secure prior informed consent for ABS (Articles 6 and 7). Some of the other major concerns are the lack of: special provisions for non-commercial research (Article 8), provision for transboundary collaboration (Article 11), a system to deal with traditional knowledge (Article 12), engagement of a National Competent Authority (Article 13), arrangement to provide relevant information to the ABS clearing house mechanism (Article 14), and facility to develop models for code of conduct and best practices (Article 20). The Government of India may have to address these gaps on a priority basis to fulfil obligations under the Nagoya Protocol.

The ABS framework and processes for approval requires more clarity for developing a rational benefit sharing system. Also, benefit sharing overlooking sector-specific problems of commercialization and profit making (included in ABS guidelines notified in November 2014) would hamper the smooth enactment of ABS in India. To help compliance to the protocol, the country has published the ‘Guidelines on access to biological resources and associated knowledge and benefits sharing regulations, 2014’. The Guidelines focus on monetary assessments for ABS purposes, developing legal instruments for ABS and developing it as an effective funding mechanism at the national level. Other clauses in the Guidelines include: support for a collaborative framework on ABS using ABS contracts, the need of a multi-dimensional compliance system, and establishing a unified and efficient authority system at the national level. The method of benefit sharing while accessing biological resources for commercial purposes is also included (National Biodiversity Authority 2022b).

Access and benefit sharing: case studies from India

Of the various opportunities for ABS in India, the red sanders case (2015) prompted the NBA, SBB and local communities to accept ABS while exporting biological resources. In this example case, the government conducted a global e-auction for the sale of red sanders, Pterocarpus santalinus L.f. (Fabaceae), a highly valued timber species. The successful purchasers were required to pay 5% of the total benefits, of which 95% were allocated for use at the local level. Thus, this ABS functioned as a source of income to the local communities while involving them in decision-making (Nlsabs 2022). Another case was the export of the red alga, Kappaphycus alvarezi (Doty) Doty ex Silva (Solieriaceae) from the Gulf of Mannar, Tamil Nadu by PepsiCo India Holdings Pvt. Ltd. The arrangement suffered a setback when the purchasers failed to distribute the benefits to the 754 claimers in the local community until 2010 due to a technical lapse. Thereafter, PepsiCo arrived at an annual agreement with the NBA to export the red alga for commercial utilization. Another example is that of Novozymes Biologicals Inc. of the USA that approved an ABS agreement with the NBA for export and commercial use of species of the bacteria Bacillus (Bacilliaceae) and Pseudomonas (Pseudomonadaceae) from the Malampuzha Forest Division, Kerala. Since 2004, the NBA receives 5% as annual royalty from the total sale of the product developed using the biological resource.

The ABSCHM records (https://absch.cbd.int/en/countries/IN/IRCC) show several cases of access to genetic resources from India including fungi, bacteria, and other microorganisms. However, there are no reported instances or cases so far on the commercial use of accessed biological resources for biological control.

Impact of ABS on the exchange of natural enemies and their evaluation as potential biological control agents

All explorations for potential biological control agents in India have been so far conducted under a collaborative mode through a Memorandum of Agreement (MoU) with the exporting/importing nation and the Government of India. The need for transfer of biological resources under such collaborative projects is usually referred to the NBA for approval. As per norms, permission to search for natural enemies of Himalayan balsam carried out in the Indian part of the Himalayas (Ellison et al. 2020) was accorded by the local biodiversity authority. Based on the agreement, samples of organisms collected, namely insects and pathogens, were to be deposited in the designated national repository notified under the BDA (National Biodiversity Authority 2022a). These explorations were for research and/or classical biological control purposes only and with no commercial multiplication of natural enemies for profit by any organization.

It is now mandatory that a collaborative research programme with the recipient country is required if it desires to export a natural enemy for biological control of an IAS from India. Exploration for the natural enemy, host specificity tests in association with the Indian partner, permission from the NBA and depositing samples in designated repositories can all be carried out if these are included in the workplan in the MoU/bilateral/multilateral agreement. Permission to export the biological control agent will be accorded by the Department of Agriculture Research and Education under the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare. Additionally, an affidavit stating that the proposed collaborative research agrees with the regulations of the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change has to be produced by the collaborator as per Clause (a) of sub-Sect. (3) of Sect. 5 of the BDA, 2002 (National Biodiversity Authority 2014). Guidelines on ABS and the associated knowledge sharing issued by the NBA in 2014 specified that approval of the NBA or SSB is not necessary for transfer or exchange of biological resources or information thereof, if this forms a part of a collaborative research project as indicated above (National Biodiversity Authority 2022c) (Fig. 2). However, any multiplication for commercial use and release of a natural enemy in another country would fall within the purview of the guidelines of ABS included in the BDA.

Flow chart for access and benefit sharing procedure in India (National Biodiversity Authority 2022c)

For the import of natural enemies, the regulations of the exporting country would apply and the Plant Protection Advisor, Government of India under the Directorate of Plant Protection, Quarantine and Storage, Faridabad is responsible to grant permission under the Plant Quarantine (Regulation of Import into India) Order, 2003. However, the BDA rules do not apply for exporting any exotic biological control agents that were imported and already established in India. But a certificate issued by a competent authority needs to accompany each shipment confirming the exotic nature of the biological control agent for export. Also, a voucher specimen or sample of the species is expected to be deposited in a recognized repository prior to export (Sreerama Kumar et al. 2022).

Conclusions

To rectify the hurdles in enacting ABS in India, it is recommended that: (1) the policies of the user country may include clauses to minimise misuse of biological resources accessed; (2) the consent of local communities be sought before accessing resources instead of just ‘consulting’ them as stipulated by the BDA; (3) the provisions of ABS be clearly spelt out especially what are covered by the BDA and what are not covered; (4) compliance to ABS provisions may be made easier through flexible approaches; and (5) the roles and responsibilities of each actor, the Ministry, the NBA, the SSB and BMC in implementing ABS may be clearly defined. The above proposals, if applied, would help proper implementation of the Nagoya Protocol in the country. It is helpful that India has a legal framework in operation to comply with the CBD regulations including ABS. Hence, collaborative efforts between the relevant ministries and the stakeholder groups may assist to realize the full potential of ABS and to remove the hurdles in implementing its provisions. The ABS aims not only to conserve and use genetic resources sustainably but also to improve livelihoods of local communities.

References

Brahmi P, Choudhary V, Tyagi V (2021) An overview of framework and case studies related to ABS in plant genetic resources. Indian J Plant Genet Resour 34:25–34

Cabrera MJ, Tvedt MW, Perron-Welch F, Jorem A, Phillips F-K (2013) The interface between Nagoya Protocol on ABS and the ITPGRFA at the international level: potential issues for consideration in supporting mutually supportive implementation at the national level.https://www.fni.no/getfile.php/131657-1469868920/Filer/Publikasjoner/FNI-R0113.pdf

Claudio C (2008) The question of minimum standards of access and benefit-sharing under the CBD international regime: lessons from the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. Asian Biotech Dev Rev 10:3

Cock MJW, van Lenteren JC, Brodeur J, Barratt BIP, Bigler F, Bolckmans K, Cônsoli FL, Haas F, Mason PG, Parra JRP (2010) Do new access and benefit sharing procedures under the Convention on Biological Diversity threaten the future of biological control? BioControl 55:199–218

Convention on Biological Diversity (2008) Report of the meeting of the group of legal and technical experts on concepts, terms, working definitions and sectoral approaches. https://www.cbd.int/doc/meetings/abs/abswg-07/official/abswg-07-02-en.pdf. Accessed 16 November 2022

Convention on Biological Diversity (2011) Nagoya Protocol on access to genetic resources and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from their utilization of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal, Canada

Convention on Biological Diversity (2022a) The convention on biological diversity. https://cbd.int/convention. Accessed 15 Nov 2022

Convention on Biological Diversity (2022b) Access and benefit sharing clearing house. Country records India. http://absch.cbd.int/search/nationalRecords. Accessed on 15 Oct 2022

Ellison CA, Pollard KM, Varia S (2020) Potential of a coevolved rust fungus for the management of Himalayan balsam in the British Isles: first field releases. Weed Res 60:37–49

Garforth K, Frison C (2007) Key issues for the relationship between the Convention on Biological Diversity and the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. Occasional Paper No. 2. Quaker International Affairs Programme, Ottawa, Canada. https://biogov.uclouvain.be/staff/frison/OP2-Final_000.pdf

Goeden RD (1978) Biological control of weeds Part II. In: Clausen CP (ed) Introduced parasites and predators of arthropod pests and weeds: a world review. Agriculture Handbook 480, Agriculture Research Service, USDA, Washington DC, USA, pp 357- 414

Halewood M, Andrieux E, Crisson L, Gapusi JR, Mulumba JW, Koffi EK, Dorji TY, Bhatta MR, Balma D (2013) Implementing ‘Mutually Supportive’ access and benefit sharing mechanisms under the Plant Treaty, Convention on Biological Diversity, and Nagoya Protocol, 9/1 Law, Environment and Development Journal, p. 68, http://www.lead-journal.org/content/13068.pdf. Accessed 12 October 2022

Heimpel GE, Mills NJ (2017) Biological control. Cambridge University Press, UK

IEEP, Ecologic and GHK (2012) Study to analyse legal and economic aspects of implementing the Nagoya Protocol on ABS in the European Union. Executive Summary of the Final report for the European Commission, DG Environment. Institute for European Environmental Policy, Brussels and London http://minisites.ieep.eu/assets/1225/ABS_executive_summary.pdf. Accessed 2 November 2022

ITPGRFA (2022) International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. https://www.fao.org/plant-treaty/areas-of-work/farmers-rights/en/. Accessed 12 October 2022

Mason PG, Barratt BIP, Mc Kay F, Klapwijk JN, Silvestri L, Hill M, Hinz HL, Sheppard A, Brodeur J, Diniz Vitorino M, Weyl P, Hoelmer KA (2023) Impact of access and benefit-sharing implementation on biological control genetic resources. BioControl, in press. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-023-10176-8

National Biodiversity Authority (2014) Guidelines for international collaboration research projects involving transfer or exchange of biological resources or information relating thereto between institutions including government sponsored institutions and such institutions in other countries. http://nbaindia.org/uploaded/pdf/notification/7%20%20collaborative%20guidelines.pdf. Accessed 2 November 2022

National Biodiversity Authority (2022a) The Biological Diversity Act, 2002 and Biological Diversity Rules, 2004, National Biodiversity Authority (2004). http://nbaindia.org/uploaded/act/BDACT_ENG.pdf. Accessed 10 Oct 2022

National Biodiversity Authority (2022b) Compendium of Biological Diversity Act 2002, Rules 2004 & Notifications. http://nbaindia.org/content/18/21/1/notifications.html. Accessed 15 Oct 2022

National Biodiversity Authority (2022c) Guidelines on access to biological resources and associated knowledge and benefits sharing regulations, 2014. http://nbaindia.org/uploaded/pdf/Gazette_Notification_of_ABS_Guidlines.pdf. Accessed 18 Oct 2022

National Biodiversity Authority (2022d) Access and benefit sharing experiences from India. http://nbaindia.org/uploaded/pdf/ABS_Factsheets_1.pdf. Accessed 15 Nov 2022

Nijar GS (2011) Food security and access and benefit sharing laws relating to genetic resources: promoting synergies in national and international governance. Int Environ Agreements 11:99–116

Nlsabs (2022) Biodiversity and access and benefit sharing in India https://abs.nls.ac.in/?page_id=219. Accessed 15 November 2022

Pisupati B (2015) Access and benefit sharing: issues and experiences from India. Jindal Global Law Review 6(1):31–38

Sankaran KV, Suresh TA (2013) Evaluation of classical biological control of Mikania micrantha with Puccinia spegazzinii. KFRI Research Report No. 472, Kerala Forest Research Institute, India

Sankaran KV, Puzari, KC, Ellison CA, Kumar PS, Dev U (2008) Field release of the rust fungus Puccinia spegazzinii to control Mikania micrantha in India: protocols and raising awareness. In: Julien MH, Sforza R, Bon MC, Evans HC, Hatcher PE, Hinz HL, Rector BG (eds), Proceedings of the XII international symposium on biological control of weeds, Montpellier, France, 22–27 April 2007. CAB International, Wallingford, pp 384–389

Sankaran T (1973) Biological control of weeds in India: a review of introductions and current investigations of natural enemies. In: Dunn PH (ed) Proceedings of the second international symposium on biological control of weeds, Rome, Italy, 4–7 October 1971, Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux, Slough, UK, pp 82–88

Singh SP (2001) Biological control of invasive weeds in India. In: Sankaran KV, Murphy ST, Evans HC (eds) Alien weeds in moist tropical zones. Proceedings of a workshop, 2–4 November 2001, Kerala, India, Kerala Forest Research Institute, India and CABI Bioscience, UK, pp 11–19

Sreerama Kumar P, Sreedevi K, Amala U, Gupta A, Verghese A (2022) Shipment of insects and related arthropods into and out of India for research or commercial purposes. Rev Scie Tech/Off Int Des Epizooties 41(1):158–164

Thomas G, Moreno SP, Åhrén M, Carrasco JN, Kamau EC, Medaglia JC, Oliva MJ and Perron-Welch F, Ali N, China W (2012) An explanatory guide to the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing. IUCN Environmental Policy and Law Paper No. 83, https://doc1.bibliothek.li/abd/FLM9151088.pdf Accessed 2 November 2022

Tryon H (1910) The ‘wild cochineal insect’, with reference to its injurious action on prickly pear (Opuntia spp.) in India, etc., and to its availability for the subjugation of this plant in Queensland and elsewhere. Queensland Agric J 25:188–197

Tvedt MW (2014) Beyond Nagoya: towards a legally functional system of access and benefit-sharing. In: Oberthur S, Rosendal GK (eds) Global governance of genetic resources access and benefit sharing after the Nagoya Protocol. Routledge, UK, pp 158–177

Winston RL, Schwarzlander M, Hinz HL, Day MD, Cock MJW, and Julien MH (2023) Biological control of weeds: a world catalogue of agents and their target weeds. Based on FHTET-2014–04, USDA Forest Service, Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team. https://www.ibiocontrol.org/catalog/. Accessed 27 Feb 2023

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr ST Murphy, CABI Bioscience, UK Centre, Egham and the two anonymous reviewers for useful comments on the manuscript. We also thank Dr R Suganthasakthivel, Kerala Forest Research Institute, India and Dr Keerthy Vijayan for helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There were no potential conflicts of interest between the authors while preparing this paper.

Human and animal rights

Humans or animals were not involved in this research.

Consent for publications

Consent of all the authors were taken before submitting this paper.

Additional information

Handling Editor: Peter Mason

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gupta, K., Sankaran, K.V. & Kumar, P.S. Exchange of biological control genetic resources in India: prospects and constraints for access and benefit sharing. BioControl 68, 281–289 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-023-10199-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-023-10199-1