Abstract

Anyone interested in philosophical argumentation should be prepared to study philosophical debates and controversies because it is an intensely dialogical, and even contentious, genre of argumentation. There is hardly any other way to do them justice. This is the reason why the present special issue addresses philosophical argumentation within philosophical debates. Of the six articles in this special issue, one deals with a technical aspect, the diagramming of arguments, another contrasts two moments in philosophical argumentation, Antiquity and the twentieth century, focusing on the use of refutation, and the remaining four analyze particular philosophical controversies. The controversies analyzed differ significantly in their characteristics (time, extension, media, audience,…). Hopefully, this varied sample will illuminate some salient aspects of philosophical argumentation, its representation and variations throughout history. We are fully aware that, given the scarcity of previous studies of philosophical debates from the perspective of argumentation theory, the following specimens of analysis must have several shortcomings. But it is a well-known adage that the hardest part is the beginning. That is what we tried to achieve here, no more, but no less either.

Similar content being viewed by others

‘Philosophy was born in controversy and thrives on controversy’, says a recent author (Gracia 2004, x), and we agree. In spite of this fact, disputes among philosophers have not often been subjected to the kind of analysis and evaluation which we are used to in argumentation theory. This special issue has the purpose to make a start by approaching this complex subject from multiple perspectives. The question we started from, suggested to us by the editor-in-chief of this journal, concerns the role of argumentation in philosophical controversies. We put this question to a number of scholars whom we knew to have an interest in the particular kind of dispute that philosophers get involved in; but we did not insist on this apparent implication, nor did we set any limits to the approach to be taken. The only condition was to choose one particular case and to relate their discussion to it. Some of the scholars we invited were sufficiently intrigued to accept to take part in this venture. Reading their work has prompted us to the following reflections.

1 Whence Can We Expect a Theory of Philosophical Argumentation?

Philosophy has the longest continuing history of argumentation and controversy in Western civilization.Footnote 1 Other disciplines or fields—medicine, law, rhetoric, history, mathematics—may be said to be equally old or even older than philosophy, but their practitioners hardly ever seriously consider what their ancestors wrote or thought. The history of philosophy is indeed full of accidents and detours, but it started about two and a half millennia ago and we are still at it; and, although some of its characters and some of its questions have faded away from time to time, they always have a knack for re-entering the philosophical conversation sooner or later.

From the beginning, philosophers have directed their acuity of mind towards the claims and arguments made by other philosophers as well as themselves.Footnote 2 For it was in philosophy that the very concepts of claim and argument were first invented; and it was philosophers who pioneered their analysis and evaluation. In that respect, we could say that philosophers have always had what Peirce called a logica utens—a theory of philosophical argumentation largely implicit in the different ways they have tried to analyze and evaluate philosophical claims and arguments. It is true that a few attempts at establishing the building blocks for a logica docens—an explicit theory of philosophical argumentation—have been made from time to time. Aristotle’s dialectics, Descartes’ celebrated method, Kant’s transcendental logic, Russell’s theory of definite descriptions, are good examples of that. However, none of them amounts to a theory of philosophical argumentation in the sense of the contemporary field of argumentation theory.

On the other hand, we must take into account that contemporary argumentation theory was born from the fear that modern state propaganda, the advertisement industry, and the increasing production of hoaxes, fake news, and conspiracy theories may have deleterious effects on the behaviour of citizens and voters in contemporary democracies. So, it was natural that the main efforts of argumentation theorists have thus far been mainly directed to argumentation in the mass media. Other areas of argumentative activity that have attracted some moderate interest from argumentation theorists are medicine and the law.Footnote 3 Yet philosophy has scarcely been a top priority in the agenda of argumentation theorists, apart from a few exceptions that will be mentioned later on. In any case, the main goal of this special issue is to exemplify some new tools and questions as they may be applied to the task of better understanding how philosophers argue.

2 Philosophy of Argumentation vs Philosophical Argumentation

Regarding the relations between philosophy and argumentation theory, there are two main foci of interest: philosophy of argumentation and philosophical argumentation.

Argumentation, like any other practice (education, technology, religion, sport, etc.), can be a subject for philosophical reflection, thus giving rise to a philosophy of argumentation. This raises the question of what the relationship of the philosophy of argumentation to argumentation theory should be. Wayne Brockriede considers these two labels interchangeable: “one necessary ingredient for developing a theory or philosophy of argument is the arguer himself” (Brockriede 1972, 1, emphasis added). As is well known, informal logic was introduced in 1978 as a new philosophical discipline, recognized by the International Federation of Philosophical Societies (FISP) under the rubric of ‘philosophy of argumentation’ (Johnson and Blair 1980, p 25–26). This identification of informal logic with the philosophy of argumentation has subsequently been insisted upon by authors such as Trudy Govier (1999) and David Hitchcock (2000). The philosophy of argumentation, finally, can also be understood as a second-order discipline, which reflects on argumentation theories, as does J. Anthony Blair:

This chapter is an essay in the philosophy of argument. It recommends a way of conceptualizing argument and argumentation. The goal is to construct a framework in terms of which various particular theories of argument can be seen to have their place, and the various controversies in the field of argument studies can be located. I argue that the recommended conceptualizations have the implication that some of the controversies have (Blair 2012a, b [2003], 171).

This special issue is not devoted to the philosophy of argumentation but to philosophical controversies—that is, to philosophical argumentation. Approaching philosophical argumentation from the theory of argumentation implies considering it as an argumentative practice among others, such as legal, political, medical, scientific, artistic, etc. argumentation. The assumption is that the practice of philosophical argumentation has certain characteristics of its own, although neither necessarily exclusive nor invariant over time. This is the focus of most of the contributions in this special issue on philosophical controversies.

The practice of philosophical argumentation can be addressed from a descriptive approach: ‘how do philosophers argue?’, or from a normative approach: ‘how should philosophers argue?’. The normative approach corresponds to what could be called ‘philosophical argumentation theory’. Indeed, for many authors, the adjective ‘philosophical’ is closely associated with the study of normativity:

So understood, Argumentation Theory would be the philosophical task of characterizing the normative activity of arguing and its underlying conception of argumentation goodness; and this transcendental conception of Argumentation Theory would be called to play a central role within epistemology, theories of rationality, and any other field in which normative concepts such as justification, rationality, reasons or reasonableness are pivotal. (Bermejo-Luque 2016, 2; emphasis added).

All argumentative practices (practices in which asking for, giving, and examining reasons occupy a central position) are typically reflexive and self-regulating, but a feature that is often mentioned as characteristic of philosophical controversies is that they are frequently consciously argumentative. Thus, Shai Frogel insists that philosophical activity is characterized by the absence of unappealable criteria of justification and its simultaneous commitment to justification (2005, 5); Jonathan L. Cohen states that analytic philosophy is the reasoned discussion of what can be a reason for what, and deals with normative problems having to do with the rationality of judgments, attitudes, procedures and actions. (1986, 49); and Bermejo Luque contends that because philosophical practice is conducted, mostly, by arguments, suitable normative models for argumentation are necessary if philosophy is to achieve self-understanding and self-regulation. (2011, 273–274).

What does it mean that philosophical activity is consciously argumentative? Practices are inherently normative, and the description of that internal normativity is part of the description of any practice. But the label 'theory of philosophical argumentation' points to a different claim, since that theory should provide the means to assess and improve the practice of philosophical argumentation (as Bermejo Luque emphasizes in the preceding paragraph). Paula Olmos (2019) distinguishes three levels of pragmatic explicitness in argumentative practices:

-

Implicit (tacit) normativity, displayed in argumentative behavior, entails the discursive recognition of tacit reasonable links and can be expressed in the normative use of analogies and counter-analogies that compare arguments. It is the most usual level in everyday argumentative practices, learned or acquired along with language.

-

Normativity expressed and discussed in the argumentative practice itself entails the explicitness and discussion of warrants, which involve the verbalization of the proposed link between reason and conclusion. Warrants are rules that embody standards of reasonableness in force in a community or in an argumentative practice. It is typical of specialized (even professional) argumentative practices, in which reference can be made to a more conscious regulation of such standards.

-

Criticism of the current normativity: on a more sophisticated and philosophical level, one can question (and eventually modify) the status quo of a certain current standard of rationality (or the discussion of the very existence of standards of rationality) on the basis of epistemic, ethical, etc. considerations. This implies a type of critical reception that we could call, in a certain sense, ‘meta-argumentative’ and that usually takes the form of addressing the general validity of certain types of argumentative links, trying either to justify or to attack such validity.

Although this issue is not devoted to the theory of philosophical argumentation in the sense explained above, some of Catarina Dutilh Novaes’ statements fall in its field: thus dialectic is especially suitable for the philosophical purpose of questioning the obvious, or the counterexample-based approach to philosophical refutation, can give rise to philosophical theorizing on subtle disputes.

3 Philosophers on Philosophical Argumentation—a Potted History

Although it can be argued that Socrates and Plato—and even Parmenides and Zeno before them—both argued in strikingly innovative ways and reflected deeply about those new and strange ways of arguing which we came to associate with the name of ‘philosophy’, it seems pretty certain that it was Aristotle, as a young man, who first developed an apparatus for the description, analysis, and evaluation of argumentation. At the end of his first tract on the subject, he claims:

That our programme has been adequately completed is clear. But we must not omit to notice what has happened in regard to this inquiry. For in the case of all discoveries the results of previous labours that have been handed down from others have been advanced bit by bit by those who have taken them on, whereas the original discoveries generally make an advance that is small at first though much more useful than the development which later springs out of them. (…) Of the present inquiry, on the other hand, it was not the case that part of the work had been thoroughly done before, while part had not. Nothing existed at all. (On Sophistical Refutations, 183b15–36; tr. Pickard-Cambridge in Barnes 1984)

This first tract addresses the practice, by certain skilled people (whom Plato gave the sobriquet of ‘sophists’ or know-it-alls), of making people contradict themselves by setting an argumentative trap for them. Note that people who were entrapped were perfectly aware that they had been tricked; but they did not know how those tricks and traps actually worked. What the young Aristotle provided was an analytic apparatus to do exactly that. From that starting point, he proceeded to develop, in a larger treatise, a general propaedeutic for philosophical dialogue. Here a description of its purposes:

It has three purposes—intellectual training, casual encounters, and the philosophical sciences. That it is useful as a training is obvious on the face of it. The possession of a plan of inquiry will enable us more easily to argue about the subject proposed. For purposes of casual encounters, it is useful because when we have counted up the opinions held by most people, we shall meet them on the ground not of other people’s convictions but of their own, shifting the ground of any argument that they appear to us to state unsoundly. For the study of the philosophical sciences it is useful, because the ability to puzzle on both sides of a subject will make us detect more easily the truth and error about the several points that arise. (Topics, 101a25–36; tr. W.A. Pickard-Cambridge in Barnes 1984, very slightly modified)

Aristotle’s model was the Socratic dialogue as depicted in Plato’s dialogue: each one of two interlocutors were assigned one of two roles: questioner or answerer; the questions to be asked could be open (many possible answers) or closed (one answer, yes or no); the range of the questions was fourfold: definition, genus, proprium or accident. To give an example: ‘what is the definition of X?’ would be an open question concerning definition; ‘is Y an accidental attribute of X or not?’ a closed question. Aristotle wanted to train questioners to put forward a sequence of questions such that the answerer would contradict himself; and to train answerers to answer them in such a way as to avoid falling into contradiction.

In a sense, the Topics are a counterpart to the earlier Sophistical Refutations. In fact, the Topics could be called On Socratic Refutations—it would deal with legitimate criticisms of the other’s claims and arguments as much as the earlier work dealt with the illegitimate entrapments of the ‘sophists’. Together, these two works are thus the first theory of philosophical argumentation. As such, its primary interest was practical—to train students to do it well, not to incur in illegitimate argumentation and to overcome the opponent by means of legitimate argumentation. It is important to notice that arguing was done by means of asking and answering questions,Footnote 4 much as experienced lawyers build their legal arguments by the cross-examination of witnesses. In fact, the inventor of the method, Socrates, sometimes refers to it in exactly that way, almost as though he had been inspired by lawyers’ practice.

At some point in his career, Aristotle came to think that, if dialectics, as codified in the above two works, was a useful propaedeutic for the acquisition of proper scientific knowledge, dealing with merely probable or widely shared opinion, then there was room for a different discipline, dealing directly with the form of scientific knowledge itself. Thus was born what he called ‘analytic’ and we call ‘logic’, more precisely ‘syllogistic logic’.Footnote 5 The status of this extraordinary Aristotelian invention is a controversial matter, which we cannot do justice to here. What we can say is that neither syllogistic logic nor its successors—from Stoic propositional logic to modern mathematical logic—can claim to be a theory of argumentation, philosophical or non-philosophical.

As is well known, Christian theology has a long history of disputation concerning the correct interpretation of Scripture. How much this practice owes to the dialectical tradition of the various Greek philosophical schools is difficult to ascertain; but the fact that Boethius did translate all of Aristotle’s ‘logical’ works into Latin and wrote extensive commentaries on them is an indication that such a connection is likely.Footnote 6 However that may be, the Middle Ages inaugurated a new method, the so-called ‘scholastic method’ (Grabmann 1909), at whose centre was the quaestio. This was both a research method and a method for the organization of knowledge. It was used in all four faculties: the lower, or philosophical faculty, as well as the three higher ones—theology, law, medicine (Lawn 1993). At its core was a closed question, ‘whether something is the case or not’, having only two possible answers, ‘yes, it is the case’ and ‘no, it is not the case’. A master assigned two groups of students the task of finding arguments, one group for the affirmative, another for the negative.Footnote 7 Then a meeting was convened in which the two groups presented their findings. The master then engaged in a usually very sophisticated and often long argumentation chain, weighing up the merits and demerits of each side and deciding which was right or whether the truth was somehow divided between the two positions.

Naturally enough, this argumentation involved drawing a certain number of distinctions, some consecrated by tradition, some new. Good disputations of this kind were attended by a public of students and scholars, many of them travelling from other universities, so that the results of disputations were widely shared in the ‘republic of letters’. Thus, a body of knowledge consisting of these materials slowly accumulated, so that from time to time an adventurous thinker took it upon himself to produce a summa of such ‘questions’, a kind of companion or handbook for use by scholars and students in the whole learned world. An egregious exemplar of this kind of writing, perhaps the most important one, is the Summa Theologiae by Thomas Aquinas (Grabmann 1919; McGinn 2014). In this extraordinary book we can distinguish the main features of the art of summary: a variable number of closed questions, called articuli, have to be collected together as jointly throwing light on one general problem (say, the ends of man); such a general problem was called a quaestio, which sometimes, but by no means always, can be straightforwardly expressed as an open question. Thus, Aquinas’ Summa contains about 600 quaestiones, which are again grouped together in four unequal parts, sharing a common theme. All in all, the Summa discusses over 2500 closed questions in as many articuli. The art of the summa represents a logic utens, an implicit theory of argumentation whose three main components are: the reduction of general problems to closed questions; the marshalling of arguments in favour of one or the other alternative expressed in those closed questions; and a deployment of concepts, claims, definitions, distinctions, and arguments to decide to which alternative belong the strongest reasons.

What we do not have in a summa or in any other book made up of quaestiones is an explicit theory of argumentation that would describe and support the procedure followed in thus organizing the material.

Early modern Europe may be said to start when Bacon, Hobbes, and Descartes vehemently argued that medieval ‘logic’—as taught explicitly in ‘logical’ treatises or presumably as evinced in the literary genre of quaestiones—was a sterile enterprise, only capable of arranging already known truths but utterly unable to help us find new ones, and in addition full of strange words with dubious meanings. Instead, they started a new project, namely, to identify the sources and limitations of our knowledge, and to spell out the method that we should follow in order to attain new knowledge from those sources without trespassing the limits of what we can know.Footnote 8 This project of modernity has haunted us ever since, giving birth to one philosophical school after another up to the present day. Has this project also managed to produce a theory of philosophical argumentation? At most it can be said to have provided us with pointers in certain directions: the importance of induction as well as its troubles (Bacon, Hume, Whewell, logical positivism), the seductions of mathematical proof (Descartes, Leibniz, Spinoza, Frege, Russell), the need to recognize something like ‘transcendental arguments’ (Kant, Husserl, contemporary analytic and ‘Continental’ philosophy), the occasional attacks on certain forms of argumentation (e.g. the four ‘idols’, the is–ought problem, the ‘naturalistic’ fallacy, the ‘verification’ principle). However, a few swallows do not make a spring; and a few aperçus do not make a theory.

On the other hand, along the twentieth century we can recognize a few adventurous spirits who did try at least to sketch a theory of philosophical argumentation: Leonard Nelson (1921/2016), Robin G. Collingwood (1933, 1939, 1940), Chaïm Perelman (1945, 1949, 1958/1969), Henry W. Johnstone, Jr. (1959, 1978), Nicholas Rescher (1978, 1987, 2009), Lawrence H. Powers (1995). However, all of them, as far as we can tell, have failed to attract followers who would develop a proper theory from their valuable insights.Footnote 9 What we do have instead is an entirely new field—argumentation studies and, within it, argumentation theory—that did not emerge from philosophy, nor has it been recognized as part of philosophy. It is to this field that we now turn our attention; but we can perhaps anticipate the main points: argumentation theory is a field on its own that has a clear agenda and a healthy variety of views; philosophers are certainly part of the effort, together with academics of other areas (law, communication, linguistics, rhetoric, debating, critical thinking, cognitive science, social science), but argumentation theory is not a part of philosophy; the theory can and should be applied to all sorts of argumentation, including the philosophical; so, philosophy is just one more area of application of the concepts and methods of argumentation theory; if philosophy, or any other area of application for that matter, has certain special properties, then the application should be carefully adapted to them.

4 The New Field of Argumentation Theory

Argumentation theory was born from a specific theoretical challenge, issued by the Australian logician Charles L. Hamblin in his book Fallacies (1970). Before this book, people interested in the analysis and evaluation of arguments had made a fairly uncritical use of the term ‘fallacy’—unclearly defined and often inconsistent with the actual example of fallacies identified—a congeries of ill-assorted cases that started more or less with a selection from Aristotle’s list in On Sophistical Refutations and adding all kinds of new specimens along the way. Hamblin described what he called ‘the standard treatment’ and showed beyond reasonable doubt that it was theoretically bankrupt. Now, given that the standard treatment of fallacies was the main, if not indeed the sole weapon in separating good from bad arguments (bad arguments being those that committed fallacies), Hamblin’s demonstration was a direct and peremptory challenge to all people interested in evaluating arguments to take thought and come up with something better.

What the decade 1972–1982 brought us was a set of four responses to Hamblin’s challenge. Each response followed a different strategy; and together they created the contemporary field of argumentation theory, which can thus be said to be exactly a half-century old.Footnote 10

Starting in 1972, the Canadian philosophers John Woods and Douglas Walton followed a ‘divide and rule’ strategy, i.e., instead of seeking a general theory of fallacies, they tried to formulate a particular theory for each fallacy, relying either on classical formal logic or on some non-classical system. They pursued this strategy since 1972 and continued to collaborate on it for ten consecutive years. To crown this theoretical activity, they published together a handbook providing methods for the evaluation of arguments according to the logical perspective (Woods and Walton 1982). Then each author has gone his own way, Walton moving steadily towards informal logic and artificial argumentation, Woods towards cognitive science and non-classical logics. The very important collection of pioneering articles that emerged from that decade-long collaboration can be conveniently consulted in Woods and Walton (1989).

The Canadian philosophers Ralph H. Johnson and J. Anthony Blair followed a very different strategy, designing and refining a systematic method of evaluation by means of three new criteria: acceptability (of the premises of an argument), relevance (of the premises relative to the conclusion) and sufficiency (of the premises to affirm the conclusion based on them). With their 1977 book Logical Self-Defense, the project known as ‘informal logic’ was born (more information in Walton and Brinton 1997; Puppo 2019). Although these three criteria have given rise to a long debate as to their appropriateness and status, the fact of the matter is that one can either redefine fallacies (as argumentative moves that fail to fulfil them) or, alternatively, one can just forego all talk of fallacies and simply use the criteria directly to evaluate the arguments on offer.

In 1978, two young Dutch academics, Frans H. van Eemeren (a linguist specialising in pragmatics), and Rob Grootendorst (a student of communication) started doing research on argumentation. In good old European tradition, they first concentrated on the history of the problems, but they did so only in order patiently to build a systematic inquiry. This culminated, in 1982, in the invention of ‘pragma-dialectics’, a theory that unites two perspectives: (a) the study of the speech acts involved in the various operations that arguers carry out during a discussion, (b) the identification of the constitutive rules that allow those speech acts to resolve an initial difference of opinion. Within this theoretical framework, traditional fallacies are revealed to be violations of the rules of a critical discussion, and those rules in their turn open the way to define hitherto unidentified types of fallacy. A whole research programme was thus launched that continues to this day. A recent survey is in van Eemeren (2018).

Finally, in 1979, the Canadian philosopher Michael Gilbert published How to Win an Argument. Note that this blockbuster title is not the author’s own but was devised by the publisher for commercial purposes; it easily misleads the reader into believing that Gilbert’s book belongs to the self-help shelves, while it is in fact a very innovative theoretical proposal; all the same, the title already hints that the target of Gilbert’s theorising is not the logician’s argument—say, a set of premises and conclusions—but rather the argument as a discussion between two interlocutors. In fact, we can summarise Gilbert’s proposal as making three points: (a) the most important and frequent discussions—’arguments’—among human beings are the ones we have every day, with other members of our respective families, our fellow students, our colleagues and bosses at work, our close friends, our neighbours; (b) those discussions have several dimensions, i.e. they are not exhausted by the orderly and ‘logical’ aspects that tend to absorb the interest of other theorists, but on the contrary they have ‘non-logical’ aspects or dimensions, among which emotions, the physical embodiment, in particular, the use of the body, and the appeal to intuitions and hunches stand out; (c) we cannot evaluate arguments if we rest content with the purely logical view, so that, if we are to speak of fallacies, we must extend this concept in non-logical directions.

5 Two Broad Types of Argumentation Theory

This is as good a place as any to distinguish two broad types of argumentation theory. Notice that the first two theoretical strategies described above (Woods-Walton and Johnson-Blair) focus on arguments in the logician’s sense, i.e., they follow the classical tendency to extract them from the argumentative conversations or texts in which we detect their presence and consider them in isolation. Naturally enough, the conversation or text in which such arguments occur always contains much else, which is considered, from both perspectives, as irrelevant and disposable—‘clutter’ in Johnson’s useful terminology (Johnson 2014, p 64–65, 70, 84, 116). In contrast, the other two theoretical strategies (van Eemeren-Grootendorst and Gilbert) start from complex communicative situations, which we can call ‘discussions’ (or ‘arguments’ in the other sense of the word). Here, we do not consider a priori that there are irrelevant or disposable elements. On the contrary, whatever the arguers say or do can in principle be important for the proper understanding of the whole argumentative process. We can therefore say that the first two founding initiatives of the field of argumentation theory, born respectively in 1972 and 1977, propose theories of arguments in the narrow sense, while the last two initiatives, from 1978 and 1979, propose rather theories of discussion or of the argumentative process. (On the distinction between types of argumentation theory, the interested reader can consult Leal and Marraud 2022, Chapter 2).

Before going on with our story, it is useful to distinguish between four areas of communicative activity in which argumentation plays a role. First, we have private argumentation, taking place in everyday life among all sorts of people: we argue with our family and friends, but also on occasion with strangers we meet by chance or in the course of our daily activities, such as shopping, asking for directions, riding on public means of transport, and so on. Then, we have public argumentation. This is the realm of democratic discussion, in canvassing, political meetings, or in the mass media or increasingly in the social media. Further, we have professional argumentation, done by lawyers in court or with a client, by physicians among themselves (e.g., in differential diagnosis or ‘doing the rounds’ in a hospital) or with a patient, by architects, engineers, administrators, managers, and so on in construction sites, business meetings, and whatnot. Finally, we have academic argumentation, that takes place in universities, colleges, research institutes, scientific conferences, laboratories, and so on. We can say that these four areas are located along an axis of increasing specialisation in knowledge and jargon, where private argumentation is at the least and academic argumentation at the most specialised pole. In public argumentation we find some amount of specialisation in comparison with private argumentation; and that modest amount comes invariably from the professional and the academic spheres (cf. Goodnight 1982). Given that professional have to talk to laypeople all the time, their argumentative activities are less specialised than those of the academics, who only talk among themselves.

Why should this be important? It is because, for a variety of reason having to do with the fact that argumentation theory was born in democratic countries, most theorists have been mainly preoccupied with private and public argumentation, as anybody looking into the books and papers written in half a century of theorising can confirm. It is true that there is an increasing interest in at least two areas of professional argumentation. One is the law, which has its own tradition of thinking about argumentation; and the other is medicine or rather the health care professions in general (including nursing and clinical psychology), especially since the advent of the movements for bioethics and evidence-based clinical practice. As far as we are aware, there is little, if any, work done in relation to other professional fields. This leaves us with academic argumentation, which is practically a virgin field. Academics, of course, are reflective people who have thought harder and written more than anyone on problems having to do with argumentation in their fields. Philosophy is just one patch within this large area; and philosophers have conducted the longest conversation on this topic in the history of the West. This fact probably induces many academics and most philosophers to be sceptical about the contribution that argumentation theory can make to the analysis and evaluation of their argumentative activities. But here, as in all questions of the same sort, the proof of the pudding is in the eating. Let us then consider the papers we managed to collect for this special issue.

6 Argumentative Styles in Philosophical Argumentation

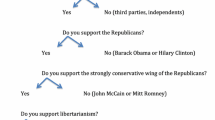

Of the six articles that make up this special issue, one deals with a technical aspect, the diagramming of arguments, another contrasts two moments in philosophical argumentation, Antiquity and the twentieth century, focusing on the use of refutation, and the remaining four analyse particular philosophical controversies. The controversies analysed differ significantly in various ways, as set forth in Table 1.

Hopefully, this variety will go some ways toward representing philosophical argumentation throughout history. Now for the details.

Shai Frogel, in ‘Bramhall versus Hobbes: the Rhetoric of Religion vs. the Rhetoric of Philosophy’, analyzes the debate between Thomas Hobbes and John Bramhall, bishop of Derry, on Liberty and Necessity. Frogel in his well-known The Rhetoric of Philosophy (2005) had characterized philosophical activity by two main features: the absence of definitive criteria of justification along with a commitment to justification, and the search for truth. These characteristics, which explain the distinctive features of philosophical argumentation, Frogel argued, recommend studying it from a rhetorical perspective, rather than from a logical perspective: “Rhetoric, which dealing with arguments whose validity is not derived from pre-determined criteria, can provide significant tools for an understanding of intellectual activity one of whose two fundamental characteristics is the absence of definitive criteria of justification along with a commitment to justification.” (o cit., 5–6).

Frogel had already claimed in the same book that when philosophy is subjected to binding criteria of justification, it stops being philosophy and turns into science or religion (op. cit., 7), and the debate between Hobbes and Bramhall, which he presents as a debate between the rhetoric of philosophy (or ‘the rhetoric of The Truth’) and the rhetoric of religion, provides him with the opportunity to deepen this contrast between two argumentative styles.

Table 2 summarizes the distinguishing characteristics of the rhetoric of philosophy versus the rhetoric of religion, according to Frogel.

As a consequence of these profound divergences, philosophy cannot accept the validity of the arguments of religion, supported on the authority of scripture and not on human understanding. And, conversely, religion cannot accept the validity of the arguments of philosophy, which appeal to human understanding and not on the authority of scripture. We are therefore faced with a non-normal argumentative exchange, in the sense of Fogelin, with a lack of shared procedures for resolving disagreements (2005/1985, 6). What then is the point of Bramhall and Hobbes’ argumentative exchange? Frogel’s response is that the value of controversies that confront incompatible types of rhetoric (or argumentative styles) is that they force opponents to address issues they would not otherwise take into consideration. Thus, Archbishop Bramhall forces Hobbes to contemplate the moral and religious implications of his view, and the philosopher Hobbes forces Bramhall to rethink his most fundamental dogmas more logically and independently. Interestingly enough, in ‘Is Natural Selection in Trouble? When Emotions Run High in a Philosophical Debate’ Fernando Leal also detects, in the controversy between Fodor and other scholars regarding the theory of natural selection, a discussion in which the theoretical question of the truth or falsity of a hypothesis and the practical question of its pernicious consequences for society are intertwined and overlapped.

Many of the features that Frogel identifies as distinctive to philosophical argumentation reappear in ‘Two types of refutation in philosophical argumentation’. Specifically, Catarina Dutilh Novaes points out that philosophical inquiry often consists in questioning the obvious and stresses the significance of refutation in philosophical inquiry. While in most scientific disciplines, empirical testing is the quintessential way to criticize or disprove scientific claims, in philosophy this functional task is primarily fulfilled by argumentative refutations. To these features, she adds that philosophical argumentation draws on more general, all-purpose socio-cognitive skills, than other argumentative practices, and a comparatively low tolerance for exceptions.

To show the significance of practices of refutation in philosophical inquiry Dutilh Novaes examines their place in ancient Greek dialectic and in the twentieth century debate on the analysis of knowledge as it developed after Gettier’s influential critique. Dutilh Novaes argues that the main difference between these two types of refutation is that in ancient dialectic it is primarily a person who is refuted while in analytic philosophy refutation aims primarily at claims and definitions. Dutilh Novaes concludes that, in general, dialectics allows a more fruitful approach to philosophical refutation than the method of counterexamples of analytical philosophy.Footnote 11 Finally, she suggests that Lakatos’s account of proofs and refutations in mathematics offers an appropriate theoretical framework for exploring the dynamics of refutations and counterexamples in philosophical argumentation.

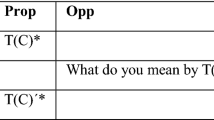

Ancient dialectic consists in conversations following a systematic structure: verbal matches between two interlocutors, a questioner and an answerer, in front of an audience, possibly with a referee or judge. Questioner and answerer are adversaries that cooperate to check the overall coherence of the answerer’s beliefs, to refine and improve her views and positions. This division of labor allows one to refine and improve one’s views and positions through critical scrutiny and produces significant epistemic improvement; either through a re-evaluation of one’s beliefs (in the Socratic dialectic) or through an exploration of what follows from different discursive commitments (in the Aristotelian dialectic).

We thus find in ancient dialectics the main features that Frogel and Dutilh Novaes ascribe to philosophical argumentation:

-

truth-conduciveness ensured by adversariality and cooperation between questioner and answerer;

-

questioning as a method for bringing out the commitments of the interlocutor;

-

systematic use of refutation or elenchus to test of the overall coherence of a person’s beliefs.

As a contrast to ancient dialectics, Dutilh Novaes chooses the controversy over the characterization of knowledge that began in 1963 with the publication of ‘Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?’, by Edmund Gettier, and extends to the present day in a torrent of publications facetiously known as ‘Gettierology’ (for recent surveys see Hetherington 2016, 2019). Certainly, this controversy is very different from those of ancient dialectics, which were developed through the oral communication of a small number of participants, over a limited and relatively short period of time. The controversy about the nature of knowledge that Gettier triggers is fundamentally developed in a written medium, over (for the moment) 60 years, and with an indeterminate number of participants. Perhaps it would be more accurate to describe it as a network of controversies connected to each other in various ways.

Although refutation continues to play a fundamental role in contemporary philosophical controversies, it now consists of presenting counterexamples, based on our intuitions, to a definition or a statement. This refutation procedure reveals the influence of the founding fathers of analytic philosophy. On the one hand, the use of counterexamples to refute strict generalizations reveals the influence of mathematical logic and mathematical modes of argument, stemming from Bertrand Russell. On the other hand, the role of intuitions is an inheritance of G. E. Moore’s vindication of common sense. In fact, the debate on the nature of knowledge starts with a proposed definition (to know something consists in justifiably believing something true), continues with the formulation of imaginary counterexamples, to which one can reply either by modifying the proposed definition or by trying to show that they are not really counterexamples: “Various iterations of these epicycles ensued, yielding increasingly convoluted new analyses of knowledge, which in turn gave rise to new, often far-fetched counterexamples to the new proposals.”

Dutilh Novaes identifies three weaknesses in the counterexample method:

-

These extremely implausible scenarios may say very little about notions of knowledge that are relevant to everyday life experiences.

-

Our intuitions about what should or should not be counted as knowledge in these unlikely scenarios may be less than reliable.

-

The assumption that an analysis of knowledge must give the exact scope of the concept, allowing no exceptions, alienates philosophical argumentation from more familiar argumentative practices.

While this may be consistent with the idea that philosophy should defy common sense, it also confers on philosophical argumentation characters that distance it from everyday argumentation, with the risk of becoming “hairsplitting disputes over overly abstract, ethereal issues by means of fanciful examples and strange thought experiments”.

In the final part of ‘Two types of refutation in philosophical argumentation’, Dutilh Novaes proposes to draw inspiration from Lakatos’ Proofs and Refutations, conceived to discuss the dynamics of argumentation in mathematics, to have a systematic description of the dynamics between arguments, refutations, and counterexamples in philosophy, or at least in those areas of philosophy significantly influenced by mathematical reasoning. In addition, moving from description to prescription, Proofs and Refutations can provide guidelines for correctly using the counterexample method of analytic philosophy while avoiding its weaknesses.

Dutilh Novaes presents Lakatos’s distinctions, concepts, and rules, and illustrates them with reference to the polemic on the analysis of knowledge. She devotes special attention to the Lakatosian typology of responses to counterexamples: surrender response, monster-barring response, exception-barring response, and lemma-incorporation response. She contends that the occasional use of monster exclusion to dismiss far-fetched counterexamples, which Lakatos discourages in mathematics, would allow philosophical inquiry to remain adequately connected to human experiences while still questioning the obvious.

The conclusion that “Lakatos’ rules for the method of proofs and refutations provide sensible guidance also for philosophical inquiry” is, however, ambiguous. Dutilh Novaes’ starting point was that these rules allowed a good description of the way in which philosophical argumentation actually takes place, but the point of arrival seems to be that these rules would help to improve it and should be followed by philosophers.

7 Three Philosophical Controversies Analyzed

Frogel and Dutilh Novaes’ contributions evoke a starkly rational image of philosophical argumentation: a search for Truth through argument and refutation, which takes nothing for granted. By contrast, the three articles in this issue that analyze particular philosophical controversies highlight their emotional charge, manifested in ironies, biased interpretations, disqualifications and even insults. It seems implausible that this coincidence, in three very different debates, can be explained only by the more or less bilious nature of some of the protagonists. Regardless of their theoretical or metaphilosophical merits, the three papers offer a detailed, almost step-by-step analysis of philosophical controversies, whose rarity is valuable in its own right.

Joaquín Galindo’s article, ‘Primatologists and Philosophers debate on the Question of the Origin of Morality’, is, among other things, a dialectical analysis of the pitfalls of cross-disciplinary disagreement. He analyzes the Tanner Lectures given by Frans de Waal in 2003, the comments by Robert Wright, science journalist, and the philosophers Christine M. Korsgaard, Philip Kitcher and Peter Singer, as well as Frans de Waal’s responses. Galindo is struck by the fact that de Waal does not take the detailed criticism of the philosophers seriously, adopting instead a mocking attitude. Galindo conjectures that this may be a fairly common reaction to some maneuvers that are more frequent in philosophical argumentation than in other fields. Philosophers often argue at length that a point of view or a question is inane, that certain statements are mere “nonsense”, “vacuous”, “uninformative”, “not a real explanation”, or that a certain argument “does not constitute a proof”, “is not a real justification”, etc. This reveals, in Galindo’s opinion, that philosophers’ arguments fulfill strategic functions that go beyond the justification of claims or the assessment of reasons. Galindo labels these additional functions as “strategic uses”. Examples of strategic uses include focusing the discussion on certain problems or refining a thesis to situate and contrast it with another family of theses and questions.

The need to capture this dual function of philosophical argumentation leads to a two-level analysis. On the one hand, it is necessary to pay attention to the macroargument that integrates the arguments of the parts, along the lines of argument dialectics (Leal and Marraud 2022, 327 and 347), and on the other, to the sequence of connected actions of the participants, conducting a dialogical analysis (Walton and Krabbe 1995). The description of this sequence of actions is made in terms of dialectical operations, which Galindo describes in detail, grouping them into four categories: starting and reformulation operations; requests for concatenation and warrant; counterconsiderations and counterargumentations; and structural strategic operations. The successive application of these operations forms “dialectical sequences”, which make it possible to capture the strategic uses of philosophical argumentation.

Thus, according to Galindo, in his comments to De Waal, Korsgaard follows an erotetic strategy, Kitcher an exploratory strategy, and Singer a self-refuting strategy. These strategies, and the corresponding dialectical sequences, can be considered typical of philosophical argumentation. Erotetical strategies dismiss questions that were previously regarded as appropriate to redirect the debate to other questions of greater philosophical interest. Erotetical strategies seek, in general, to change a presumption for or against one question, as it happens with philosophical questions that challenge common sense presumptions.

Kitcher’s exploratory strategy seeks “to focus the position more precisely by articulating a particular version of what de Waal might have in mind” (De Waal, 2006, 121). Notice that this clarificatory version of the opponent’s argument is distinct from the four versions of an argument distinguished by Joseph Wenzel (2006/1990, 17): the version in the mind of the speaker, the version overtly expressed in discourse, the version formed in the mind of the hearer, and the version reconstructed by the logician for purposes of examination.

Self-refutation strategies are closely connected with Frogel’s ad hominem arguments and the elenchus of ancient dialectics. However, according to Galindo, the type of inconsistency pursued in self-refutation strategies does not consist in showing that the opponent held ‘p’ and ‘not p’ at different times, nor in showing that his claims imply the assertion of a logical contradiction, but that, if the opponent were to apply what he holds to his own thesis, he would find it to be false. It is therefore not a logical inconsistency, but a deontic-praxiologic inconsistency, in the sense of Woods and Walton (1989, 63), as it contravenes the precept that a man must practice what he preaches.

Just as de Waal does not take seriously the detailed criticism of the philosophers, the participants in the debate on Darwin’s theory of natural selection held in The London Review of Books in 2007–2008, analyzed by Fernando Leal, insult the opponent, accuse him of being ignorant, confused and mistaken, patronize him, and ignore relevant parts of his argument. In traditional terms, the debate is riddled with fallacies. However, the participants are high powered academics. This leads Leal to reject an explanation of the behavior of Fodor and his critics in terms of fallacies. Instead, Leal proposes to use Michael Gilbert’s (1994) concept of ‘emotional argument’: the seemingly fallacious arguments are in fact emotional arguments. Gilbert defined emotional arguments as “arguments that rely more or less heavily on the use and expression of emotion.” (Gilbert 1997, 83).

Leal’s explanation differs from Galindo’s, although it also involves two levels of discussion. “Behind the highly intellectual question ostensibly being discussed there lurks a different one which is more obviously emotionally charged”. Although what appears to be under discussion is a theoretical issue—viz., whether the theory of natural selection is true or not—behind there is a practical question as to whether the theory of natural selection can, or should, be criticized in a non-specialist environment. On the one hand, it could give ammunition to Christian fundamentalists who want evolution banned from schools; on the other hand, the harmful effects on society of the wild speculations of evolutionary psychologists should not be underestimated. Leal maintains that the emotional argumentation indulged in by critics was the only way in which they could have discussed the practical question behind the theoretical one. It could be understood that the emotional arguments play strategic functions that go beyond the justification of claims or the evaluation of reasons, in which case Galindo’s and Leal’s explanations of the apparently fallacious behavior of the debaters would converge with each other.

We have labeled the question of whether or not the theory of natural selection is true a theoretical question, pertaining to the domain of theoretical reasoning or argumentation, and the question of whether the possible weaknesses of natural selection can, or should, be addressed in non-specialized journals aimed at the general educated public a practical one, pertaining to the realm of practical reasoning or argumentation. But in addition, the discussion about the first question seems to recommend the analyst’s adoption of a logical perspective (cf. Wenzel 2006/1990, 16: “the ultimate logical question in a particular case is: Shall we accept this claim on the basis of the reasons put forward in support of it?”), while the debate on the second question suggests a dialectical perspective (ibid.: “On the simplest level, the dialectical perspective may come into play whenever we apply critical concepts like fairness, honesty, and the like to ordinary natural interactions”). It makes perfect sense, then, that in the concluding stage of his reply to the first round of criticisms, Fodor states a series of general morals, concerning certain failures in discussion, that Leal interprets as rules of discussion concerning how to resolve a difference of opinion on the status of the theory of natural selection.

As already mentioned, the discussion on the a fortiori and the universal is a succession of notes published in Mind over 20 years and involved several scholars. To analyze the resulting polylogue, Hubert Marraud, following Kerbrat-Orecchioni (2004, 4–6), distinguishes between turns, which correspond to the successive notes, and moves, which correspond to the argumentative actions performed in each note. In the controversy analyzed by Marraud we find, as in those analyzed by Galindo and Leal, the typical complications and difficulties of polylogues: variability in alternation patterns, general lack of balance in floor-holding, violations of speaker-selection rules, coalitions among participants, crosstalk, …

Although in the controversy about the a fortiori and the universal there are also disqualifications and insults among the participants, in ‘An Unconscious universal in the mind is like an immaterial dinner in the stomach’, Marraud does not aim at explaining their presence through the debate, but rather at measuring in some way the level of interaction among the participants. To do so, he uses the distinction proposed by J. Anthony Blair (2012a, b/1998) between engaged dialogues, quasi-engaged dialogues and non-engaged dialogues. When a party in a dialogue is permitted to offer, and in turn support, several lines of argumentation for a standpoint, it is no longer responding to a single question or challenge from the other party. That opens the possibility of quasi-engaged or non-engaged dialogues. In a quasi-engaged dialogue there is no communication between the participants about their respective counterarguments to the other’s case, and in a non-engaged dialogue, the participants conduct a dialogue only in the sense that they defend opposing positions on the same issue, but, except incidentally, they do not argue for or against, or question, each other’s arguments. Marraud’s analysis of the controversy on the a priori and the universal confirms Blair’s hypothesis that journal papers and scholarly monographs can be analyzed as turns in non-engaged or quasi-engaged dialogues. Galindo’s remarks on the pitfalls in the debate on the Question of the Origin of Morality, and Leal’s table on the omissions in criticisms of Fodor’s target paper in the Darwinism controversy also support Blair’s conjecture.

Another aspect of interest of Marraud’s contribution is that the controversy about the a fortiori and the universal, which his protagonists raise as a discussion in logic, is here interpreted as a discussion about particularism and generalism in the theory of argument. Generalism in the theory of argument claims that the very possibility of arguing depends on a suitable supply of general rules that specify what kinds of conclusions can be drawn from what kinds of data, while particularism denies this. The paradigm of such general principles are Toulmin’s warrants. According to Marraud, in the debate on the a fortiori and the universal Mercier and Schiller take the side of particularism, as opposed to Shelton, Pickard-Cambridge, Sidgwick, Turner and Mayo, who defend generalism, the predominant position today and at that time.

8 Representing Philosophical Argumentation

In ‘Representing the Structure of a Debate’ Maralee Harrell discusses, based on her teaching experience, the various tools and methods for graphically representing a debate, illustrating them with passages from the Russell and Copleston debate on the argument from contingency. The result is a good survey paper of argumentation diagramming methods and a well-founded assessment of their merits and demerits. Her conclusion is that “there is not, but needs to be, a good way to represent argumentative debates in a way that neither obscures the essential details of the exchange nor becomes too unwieldy to extract a sense of the overall debate.” To reach that conclusion, Harrell examines three types of diagramming methods: traditional box-and-arrow systems, systems deriving from Dung’s abstract argumentation framework, and mixed systems, with two levels of representation.

Although much has been written about the polysemy of the term ‘argument’, that of related terms such as ‘argumentation’ or ‘debate’ has gone more unnoticed. ‘Argumentation’ can refer either to a succession of connected actions of several agents, who ask questions, respond, ask for clarification, etc. or to a kind of interactively constructed macro-argument that integrates the arguments of the parts. In the first case, what needs to be diagrammed are the relationships between the actions of the participants; in the second, the relationships between the arguments and counterarguments of the participants. The difference is clearly seen in ‘Primatologists and Philosophers debate on the Question of the Origin of Morality’, by Joaquín Galindo, in which two different types of diagrams are used. Harrell is interested in diagramming the macro-argument that emerges from an argumentative exchange or debate.

Harrell first examines the box-and-arrow argumentation diagramming methods. Her criticism of these methods is twofold:

-

1.

They do not allow to represent complex arguments in a perspicuous way. “After 25 boxes, the usefulness of the diagrams to visualize and understand as a cohesive whole seems to deteriorate.”

-

2.

Nor do they allow us to account for the relationships between arguments, or as the author puts it, a box and arrow diagrams “doesn’t really capture the essence of the flow of the debate, physically keeping the objections and replies apart.”

The latter criticism is revelatory of the polysemy pointed out in the previous paragraph. Terms such as ‘flow’ or ‘replies’ point to argumentative processes or exchanges between two or more agents, while ‘objection’ points rather to the abstract structure (inter-argumentative relationships) of the complex argument interactively constructed by the participants.

While box and arrow methods of argument diagramming focus on representing inferential relations between statements (intra-argumentative relations), debate diagramming methods focus on representing relations between arguments (inter-argumentative relations). Debate diagramming methods, as Harrell points out, derive from Dung’s abstract argumentation framework (AAF). A characteristic feature of AAF is that it ignores the internal structure of arguments and takes as the only, or at least the basic, relationship between arguments that of attack. The author formulates two criticisms of AAF-like debate diagramming methods:

-

1.

An argument should not be accepted or rejected depending on whether it has been attacked by some counterargument, but on the truth of its premises and the strength of the support they provide for the conclusion.

-

2.

AAF-like debate diagramming methods equate “winning” a debate with making the best case for a particular conclusion, an equivalence rejected by the majority of critical thinking textbooks.

The first criticism reveals a disagreement between a qualitative and context-independent conception of logical properties, defended by Harrell and the critical thinking community, and a comparative and context-dependent conception, incorporated by the Dung-style diagramming systems. The second criticism claims the right of the logician to evaluate, from outside the debate, the logical quality of the arguments offered in it.

Robert C. Pinto contends that a distinctive mark of dialectic is the rejection of any rule or standard for argument evaluation external to the argumentative exchange:

One cannot appraise an argument from a position one takes up outside the context of the dialectical interchange in which that argument occurs. One cannot appraise an argument in the role or office of neutral judge. Appraising an argument requires one to step into the dialectical interchange, become party to it, become a participant in it. Informal logic, insofar as it seeks to be an art of argument appraisal, would turn out to be the very art of arguing itself. Plato had a name for it. He called it the art of dialectic (2001, p8-9).

If Pinto is correct, the opposition between the predominant approaches in critical thinking and abstract argumentation frameworks could be understood as an opposition between a logically oriented approach and a dialectically oriented approach.

Harrell concludes that “For using debate to teach critical thinking, it is crucial for students to interrogate both the internal structure of the individual arguments given and the relationship between these arguments in the context of the entire debate.” Consequently, the author favors a mixed system of diagramming, that can represent both intra-argumentative relationships (i.e., between the parts of the argument) and inter-argumentative relationships (i.e., between the arguments that make up the debate).

9 Conclusion

Philosophical argumentation rarely consists of an argumentative piece isolated from other pieces. Perhaps the only real cases of such isolation occur when the philosopher says or writes something that does not manage to interest anyone; and even then that unsuccessful philosopher is herself responding to what another earlier, sometimes much earlier, philosopher said or wrote. Philosophical argumentation is thus intensely dialogical and even contentious. So, if a theorist of argumentation is really interested in philosophical arguments, then she should be prepared to study philosophical debates and controversies. There is hardly any other way to do them justice. This is the reason why the present special issue addresses philosophical argumentation within philosophical debates.

We are fully aware that, given the scarcity of previous studies of philosophical debates from the perspective of argumentation theory, the following specimens of analysis must have several shortcomings. Some of them are painfully clear to us, but we hope that our readers will take the torch and take the analysis, and even the theory, of philosophical argumentation further than we were able to. It is a well-known adage that the hardest part is the beginning. That is what we tried to achieve here, no more, but no less either.

Notes

It could be and it has been argued that philosophy, or something very much like philosophy, is to be found in other civilizations. Not having the required competence, we shall not be talking about that question. To avoid boring readers with needless repetition, we beg them to add the phrase ‘in Western civilization’ where appropriate.

Philosophers have always been interested in argumentation produced by non-philosophers; but, when they engage in the analysis or evaluation of non-philosophical argumentation, their own remains philosophical. Philosophers do not turn into physicians or lawyers by studying medical or legal argumentation. Inversely, when argumentation theorists try to analyse or evaluate philosophical argumentation, they do not turn into philosophers.

Of course, there is an abundant production on legal argumentation by philosophers of law, such as Perelman, Viehweg, Wróblewski, Peczenik, Aarnio, Alexy and MacCormick. Again, philosophers of medicine and philosophically inclined physicians have launched ‘bio-ethics’ and ‘evidence-based medicine’ in an attempt to improve the quality of medical argumentation.

In fact, one of the most important technical words in logic, premise, is a translation of Greek πρότασις, which is defined by Aristotle as a kind of question!

In Aristotle’s usage, ‘logic’, ‘logical’ and logically’ are synonymous with ‘dialectics’, ‘dialectical’ and ‘dialectically’ (see Zingano 2017).

The literary genre of commentaries (ὑπομνήματα) on Plato and Aristotle, starting around 3C AD (although there is evidence of much earlier commentaries) and going on through the Islamic, Hebrew, and finally Latin Middle Ages, is characterized by an effort to identify and analyse the philosophical arguments expressed or implied in those texts. The most favoured methods used for that purpose are taken from the Organon, as put together by Aristotle’s posthumous editors; such applications amount to an applied theory of argumentation rather than an explicit one.

Connoisseurs will immediately recognise the similarity with the tradition of intercollegiate debating in the United States that developed towards the end of the 19C and persists to this day.

One way of conceptualizing this shift would be to say that it takes us from dialectics, as the art of conversation or, more specifically, of argumentation, to logic, understood as the method of secure reasoning. The fact that the pioneers of early modern philosophy—Bacon, Hobbes, and Descartes—had nothing but contempt for medieval dialectics and logic explains why we find very little logic in the next generation of philosophers, both the empiricists and the rationalists, with the sole exception of Leibniz. Nonetheless, Arnauld and Nicole did attempt a kind of synthesis of medieval logic and the Cartesian search for a method that would allow us to discover new truths. Kant himself, who invented the phrase ‘formal logic’, contrasted it with his ‘transcendental logic’, thereby opening the gates for a bifurcation of the way in which logic came to be conceived after him. On the one hand, we find a series of logic textbooks and treatises, starting with Hegel’s and Mill’s, and on and one until about the 1940s, which in very different ways tried to construct a philosophical logic (conflated with ontology, methodology, epistemology, and even psychology). On the other hand, we find a series of mathematicians or mathematician-philosophers who stick to the idea of formal logic, thereby creating mathematical logic, a discipline whose impressive accumulation of knowledge gave it a prestige that has made it very difficult, especially after WWII, to use the word ‘logic’ in any other way.

Johnstone tried to create an institutional framework for the development of his insights, the journal Philosophy and Rhetoric (established in 1968); but, whatever merits the journal has, it neither served for the theoretical development of Johnstone’s ideas nor did it consolidate itself as a journal on argumentation theory.

According to a widespread legend, argumentation theory was born in 1958, with the almost simultaneous publication of Stephen Toulmin’s The Uses of Argument, and Chaïm Perelman’s and Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca’s Traité de l’argumentation: La nouvelle rhétorique (English translation 1969). However, these two works had very little impact for a long while, and they were read mainly by outsiders with a view to practice, mainly in debating and in legal argumentation. Incidentally, each of these two fields has its own literature on argumentation that partly feeds from older fields, debating from rhetoric and composition in the United States, and legal argumentation from sociology, philosophy, traditional logic, rhetoric, and the common law tradition, both in the United States and in Europe. Toulmin and Perelman were incorporated to argumentation theory by van Eemeren and Grootendorst in 1978, and from there they made their way into the work of the other pioneers.

This seems to confirm the early insight of Henry W. Johnstone (1952, 1959, 1978) that the only way to refute a philosopher is ad hominem, i. e., by using her own premises against herself.

References

Barnes, J. 1984. Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation, vol. 1. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bermejo-Luque, L. 2011. Giving Reasons. A Linguistic-Pragmatic Approach to Argumentation Theory. Dordrecht: Springer.

Bermejo-Luque, L. 2016. What should a normative theory of argumentation look like? OSSA 11 Conference Archive, 122. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive/OSSA11/papersandcommentaries/122/.

Blair, J. A. 2012a [2003]. Towards a Philosophy of Argument. In: Groundwork in the Theory of Argumentation. Selected Papers of J. Anthony Blair (171–184) Dordrecht: Springer. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2363.

Blair, J. A. 2012b [1998]. The Limits of the Dialogue Model of Argument. In: Groundwork in the Theory of Argumentation. Selected Papers of J. Anthony Blair (231–243). Dordrecht: Springer. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2363

Brockriede, W. 1972. Arguers as Lovers. Philosophy Rhetoric 5(1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.2307/40237210.

Cohen, J.L. 1986. The Dialogue of Reason: An Analysis of Analytical Philosophy. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Collingwood, R.G. 1933. An Essay on Philosophical Method. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Collingwood, R.G. 1939. An Autobiography. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Collingwood, R.G. 1940. An Essay on Metaphysics. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

De Waal, F. 2006. Primates and Philosophers. How Morality Evolved. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Eemeren, F.H., and R. Grootendorst. 1978. Argumentatietheorie. Utrecht: Het Spectrum.

Fogelin, R. 1982. The Logic of Deep Disagreements. Informal Logic 25(1): 3–11.

Frogel, S. 2005. The Rhetoric of Philosophy. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Gilbert, M. 1979. How to Win an Argument. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Gilbert, M. 1994. Multi-modal Argumentation. Philosophy of the Social Sciences 24(2): 159–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/004839319402400202.

Gilbert, M. 1997. Coalescent Argumentation. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Goodnight, T. 1982. The Personal, Technical, and Public Spheres Of Argument: A Speculative Inquiry Into the Art of Public Deliberation. The Journal of the American Forensic Association 18(4): 214–227.

Govier, T.R. 1999. The Philosophy of Argument. Newport News, VA: Vale Press.

Grabmann, M. 1909. Die Geschichte der scholastischen Methode. Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder.

Gracia, J.J.E. 2004. Philosophy Confronts the Passion. In Mel Gibson’s Passion and Philosophy, ed. Jorge JE. Gracia, 91–12. Chicago: Open Court.

Hamblin, C.L. 1970. Fallacies. London: Methuen.

Hetherington, S. 2016. Knowledge and the Gettier Problem. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hetherington, S., ed. 2019. The Gettier Problem. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hitchcock, D. 2000. The Significance of Informal Logic for Philosophy. Informal Logic 20(2): 129–138.

Johnson, R.H., and J.A. Blair. 1980. The Recent Development of Informal Logic. In Informal Logic: The First International Symposium, ed. J. Anthony Blair and Ralph H. Johnson, 3–28. Inverness, CA: Edgepress.

Johnson, R.H., and J.A. Blair. 1977. Logical Self-Defense. Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson.

Johnson, R.H. 2014. The Rise of Informal Logic. Windsor: Windsor Studies in Argumentation.

Johnstone, H.W., Jr. 1959. Philosophy and Argument. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Johnstone, H.W., Jr. 1978. Validity and Rhetoric in Philosophical Argument: An Outlook in Transition. University Park, PA: Dialogue Press of Man and World.

Kerbrat-Orecchioni, C. 2004. Introducing Polylogue. Journal of Pragmatics 36: 1–24.

Lawn, B. 1993. The Rise and Decline of the Scholastic ‘Quaestio Disputata’: With Special Emphasis on Its Use in the Teaching of Medicine and Science. Leiden: Brill.

Leal, F., and H. Marraud. 2022. How Philosophers Argue: An Adversarial Collaboration on the Russell-Copleston Debate. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85368-6.

McGinn, B. 2014. Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologiae: A Biography. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Nelson, L. 1921/2016. A theory of philosophical fallacies. Translated by Fernando Leal and David Carus. Cham: Springer. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20783-4

Olmos, P. 2019. Normatividad argumentativa: “naturalización” vs. “socialización. I Congreso Iberoamericano de Argumentación. Universidad Eafit, Medellín. https://www.eafit.edu.co/escuelas/humanidades/departamentos-academicos/departamento-humanidades/debate-critico/Documents/Olmos_Normatividad_argumentativa_Naturlizaci%C3%B3n_Socializaci%C3%B3n.pdf.

Perelman, C., and L. Olbrechts-Tyteca. 1958. The New Rhetoric A Treatise on Argumentation. Notre Dames IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

Perelman, C. 1945. De la Justice. Brussels: Université Libre de -Bruxelle [English translation by John Petrie, ‘Concerning Justice’, in C. Perelman, The idea of Justice and The Problem of Argument, 1–60. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul].

Perelman, C. 1949. Philosophies premières et philosophie régressive. Dialectica 3(3), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-8361.1949.tb00862.x [English translation by D. A. Frank and M. K. Bolduc: First Philosophies and Regressive Philosophy, Philosophy and Rhetoric 36(3), 177–206. https://doi.org/10.1353/par.2003.0026.

Pinto, R. 2001. Argument, Inference and Dialectic Collected Papers on Informal Logic with an Introduction Hans V. Hansen. Dordrecht: Springer.

Powers, L.H. 1995. Equivocation. In Fallacies Classical and Contemporary Readings, ed. H.V. Hansen and R.C. Pinto, 287–301. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Puppo, F. 2019. Informal Logic: A “Canadian” Approach to Argument. Windsor, ON: Windsor Studies in Argumentation.

Rescher, N. 1978. Philosophical Disagreement: An Essay Towards Orientational Pluralism in Metaphilosophy. The Review of Metaphysics 32(2): 217–251. https://doi.org/10.2307/20127188.

Rescher, N. 1987. Aporetic Method in Philosophy. The Review of Metaphysics 41(2): 283–297. https://doi.org/10.2307/20128593.

Rescher, N. 2009. Aporetics: Rational Deliberation in the Face of Inconsistency. University of Pittsburgh Press.

van Eemeren, F.H. 2018. Strategic Maneuvering in Argumentative Discourse. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Walton, D., and A. Brinton. 1997. Historical Foundations of Informal Logic. London: Routledge.

Walton, D., and E.C.W. Krabbe. 1995. Commitment in dialogue: Basic Concepts of Interpersonal Reasoning. Albany: SUNY Press.

Wenzel. 2006/1990. Three Perspectives on Argument Rhetoric, Dialectic, Logic. In Trapp, Robert & Janice Schuetz, Perspectives on argumentation: essays in honor of Wayne Brockriede 9–26. New York: Idebate Press.

Woods, J., and D.N. Walton. 1982. Argument: The Logic of the Fallacies. Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson.

Woods, J., and D.N. Walton. 1989. Fallacies: Selected Papers 1972–1982. Dordrecht: Foris.

Zingano, M. 2017. Ways of Proving in Aristotle. In Reading Aristotle: Argument and Exposition, ed. W. Wians and R. Polansky, 7–49. Leiden: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004340084_003.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. This research has been funded by the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades-FEDER funds of the European Union support, under project Parg_Praz (PGC2018-095941-B-I00).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no potential conflicts of interest (financial or non-financial) to report.

Ethical Approval

We ensure objectivity and transparency in research, and we also ensure that accepted principles of ethical and professional conduct have been followed.

Human and Animal Rights

The research has not involved human participants; The research has not involved animals.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Leal, F., Marraud, H. Argumentation in Philosophical Controversies. Argumentation 36, 455–479 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-022-09581-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-022-09581-7