Abstract

This paper explores the interrelations between temporality and emotion in rhetorical argumentation. It argues that in situations of uncertainty argumentation affects action via appeals that invoke emotion and thereby translate the distant past and future into the situated present. Using practical inferences, a threefold model for the interrelation of emotion and time in argumentation outlines how argumentative action depends on whether speakers provide reasons for the exigence that makes a decision necessary, the contingency of the decision, and the confidence required to act. Experiences and choices from the past influence the emotions experienced in the present and inform two intertemporal mechanisms that allow speakers and audiences to take the leap of faith that defines decision-making under uncertainty: retrospective forecasting and prospective remembering. Retrospective forecasting establishes a past–future–present link, whereas prospective remembering establishes a future-past-present link, and, together, the two mechanisms provide a situated presence that transcends the temporal constraints of uncertainty. Finally, the applicability of the model is illustrated through an analysis of a speech delivered by Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, a time where the need for decisive, yet argumentative action was crucial.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction: “What You Do Today Makes a Difference”

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (W.H.O.) declared the ongoing outbreak of COVID-19 a pandemic, leading politicians around the world to advocate for decisive action. In Denmark at 8:00 p.m. CET that same day, the Danish prime minister and leader of the Social Democratic Party, Mette Frederiksen, thus began what politicians, industry leaders, and commentators shortly after dubbed “a historical press conference” (Schulz 2020), stating: “What I will say tonight is going to have major consequences for all Danes.” She then went on to announce the most drastic lockdown of Danish society in peacetime.

Forty-four minutes later, an opposition member of the Danish Parliament, Mette Abildgaard of the Conservative People’s Party, tweeted: “Good press conference by the Prime Minister. Will possibly hate myself for this tweet at the next election, but I trust her as prime minister in these very serious times.”Footnote 1

Abildgaard’s tweet illustrates that while emotions may exist and change across time (present trust, future hate), they also shape opinion and agency in the present. To make decisions under uncertainty is to feel one’s motives well up inside oneself and then act upon them (Helm 2009). While the safest bet for any decision maker might be to hold out for more data and their tantalizing promise of predictability, novel and uncertain situations amplify the dilemma between an epistemic waiting game and a prudential willingness to act incisively. Existing argumentation research suggests deliberation about choice of action (Kock 2017) under uncertain circumstances (Walton 1990; Tindale 2018) define rhetorical situations and rhetorical argumentation, essentially, as “The Realm of the Uncertain” (Kock 2020, p. 288).

Uncertainty has a both epistemic and practical character in rhetorical argumentation (Zarefsky 2020), which emphasizes the critical importance of time because a practical choice has prospective outcomes, whereas demonstration leads to true conclusions, independent of the passing of time (Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca 2020). Indeed, emotions are inevitable, especially in situations of uncertainty, but a person’s decision-making capacity also depends on them (Damasio 1994). Building on Damasio’s groundbreaking work, Barrett underlined: “Affect is not just necessary for wisdom; it’s also irrevocably woven into the fabric of every decision” (2017, p. 80).Footnote 2

The rhetorical tradition has always embraced emotion in persuasion (Katula 2003), just as it recognizes the centrality of time to persuasion (Miller 1994; Tindale 2018, p. 182). Although Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca hinted at the emotional nature of temporality in argumentation (2020, p. 319), and emotion scholars mentioned the past and future orientations of emotion (e.g., Helm 2009; Lerner et al. 2015), the temporality of appeals to emotion in argumentation studies remains largely unexplored.Footnote 3 Scott has recently encouraged further research “thematizing the essentially temporal idea of ethos” (2020, p. 35), but he and other argumentation scholars appear silent about the need to connect pathos and temporality in relation to decision making. This paper seeks to shed light on this blind spot by exploring the connection between emotions and time in argumentation.

This aspiration begins with Micheli’s call to further examine “the discursive constructs of situations and their emotional orientation” (2020, p. 15). Such discursive constructs of situations involve not only the present situation but also future projections, which argumentation may affect and act as grounds for choosing one option over another. Given that decisions happen in the now, one must understand how speakers successfully make the future––which their decisions will affect––present, using the past as a central resource. My main argument in this paper is as follows: In uncertain situations, argumentation affects action via appeals that invoke emotion and thereby translate the distant past and future into a situated present. Emotions make arguments about the future appear present, creating an opportunity for action that enables people to believe in and act on them.

I seek to contribute to rhetorical argumentation in two respects. Theoretically, understanding the temporality of emotion can strengthen our appreciation of the logos of the passions (Brinton 1988a; Waddell 1990; Micheli 2010), which, I argue, is necessary in any deliberation about choice where emotions and incommensurable values render a common yardstick for reaching a “true” conclusion futile (Kock 2017, p. 60). Societally, the year 2020 marks the outbreak of a global pandemic and the rise of a social movement against systemic racism, not to mention an ongoing climate crisis. Such consequential global crises stir the emotions, and emotions must be harnessed rhetorically to engage citizens in both the necessary decision making and to mobilize support for solutions. Now more than ever, it is apparent that emotions inevitably influence decision making (Vohs et al. 2007); the question is how to harness them rhetorically in a way that enables such decision making to be wise.

In terms of making a conceptual contribution, a three-fold model for interrelating emotion and time in argumentation can illustrate how speakers must provide reasons for (i) the exigence that makes a decision necessary, (ii) the contingency of the decision, and (iii) the confidence required to act. Experiences and choices from the past influence the emotions experienced in the present and inform two intertemporal mechanisms that allow speakers and audiences to take the leap of faith in decision making: retrospective forecasting, which establishes a past–future–present link, and prospective remembering, which establishes a future-past-present link.

To investigate the connection between temporality and emotion in argumentation, I first review the roles of time and emotion in argumentation, and then combine insights from the two strands of argumentation theory to substantiate my synthesis and propose a conceptual model of temporality and emotion in rhetorical argumentation. To illustrate the empirical import of the theoretical work, I have focused on the COVID-19 pandemic, for this sudden and dramatic development has already profoundly affected societies, putting humanity on an impending “tightrope walk to recovery” (OECD 2020). As such, the coronavirus crisis also provides a pertinent lens through which to understand how people interact and reason about which decisions to make and how to act in a situation marked by high uncertainty. To illustrate this applicability, I briefly analyze Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen’s opening speech at the March 11 press conference.

2 Temporality and Emotion in Argumentation

Argumentation is an unfolding process in which the audience is an active participant, not a “mere passive receptor” (Tindale 2018, p. 30). Although I emphasize this aspect of audience agency because of its prevalence in contemporary rhetorical theory (Hoff-Clausen 2018), I also stress that creating adherence in decision making contexts depends on whether people are committed to carrying out the (future) actions they decide on in the very present (Scott 2020). The uncertain nature of rhetoric makes time an essential factor (Zarefsky 2020, p. 301). Humans do not deliberate about matters where their words have no power, but a rhetorical situation (Bitzer 1968) implies an exigence, an urgency-laden imperfection that the audience, here defined as a mediator of change, possesses the agency to resolve, despite the existence of various constraints that reflect uncertainty about the outcome of the decision. Largely because of this uncertainty, emotions play an important role, as they emphasize salient agentic clues about what to do (Pfau 2007). The following sections briefly present contemporary conversations on temporality and emotion in argumentation to provide a foundation for developing the subsequent synthesis.

2.1 Temporality in Argumentation

Time and temporality are not synonymous. Rather, temporality is the “negotiated organizing of time” (Granqvist and Gustafsson 2016, p. 1009) that establishes “ongoing relationships between past, present, and future” (Schultz and Hernes 2013, p. 1). This definition stems from organization studies but clearly resembles that used in Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca’s seminal paper on rhetorical argumentation, in which temporality is “the intervention of time”:

The oppositions that we notice between classical demonstration, formal logic, and argumentation may, it seems, come back to an essential difference: time does not play any role in demonstration. Time is, however, essential in argumentation, so much so that we may wonder if it is not precisely the intervention of time that best allows us to distinguish argumentation from demonstration. (2020, p. 310).Footnote 4

I emphasize that the “intervention of time” plays an essential role in distinguishing argumentation from demonstration and stress that rhetorical argumentation revolves around practical choice (Kock 2017). Furthermore, where demonstration leads to true conclusions, independent of the passing of time, argumentation is an action one performs with words when seeking adherence to a proposal. Seeking adherence concerns influencing an audience to make a decision that will impact the shape of an unknown future. Hence, the notion of “argumentative action” (Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca 2020, p. 316) underlines the dynamism of persuasive symbolic action, which provides compelling reasons both for taking action and for the very action that stems from such argumentation.

A key aspect here is the question of how the concept of temporality, as a constituent part of argumentation, is capable of “translating” or moving the past and future into the present: “Argumentation confers simultaneity on elements that normally would be distant in time, a simultaneity that derives from their integration in a system of ends and means, of projects and obstacles.” (Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca 2020, p. 329).

This simultaneity exists when an audience comes to understand that the decisions it makes have future consequences, vague though such distant futures might seem when viewed from the present: the future simply lacks presence, one could say. The ability to invoke presence, a key term in Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca’s theory of rhetorical argumentation (1969, p. 115), is crucial in argumentation involving future considerations. Persuasion hinges on the question of how imagination of the future becomes present in the moment of deliberation. As a rhetorical ability, then, creating presence revolves around the choice of certain salient elements and their presentation to the audience, as persuasive appeal arises from the importance with which a speaker endows these elements simply by choosing to focus on them (Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca 1969, p. 116).

When a speaker focuses on certain elements, creating a salience in the presence anticipating what is yet to come and how choices can impact such a foreseen future, the concept of prolepsis is worth mentioning, as it “allows our attention to be directed to particular deliberative ends” (Mehlenbacher 2017, p. 246). Stemming from the Greek word prolambanein, to anticipate, (Walton 2008, p. 144), proleptic argumentation can be understood as both a rhetorical figure anticipating a premise yet-to-happen and a subsequent consequence (e.g. ‘If you tell mom, I will never help you again ‘) and several argument tactics distinguished by their varying certainty of future outcomes. Prolepsis can namely be both (i) an anticipation and rebuttal of an opponent’s argument, (ii) a certain prediction of future events, and as iii) presage, a forewarning of a potential future (Mehlenbacher 2017, p. 235); the latter being highly relevant to the current paper, and an aspect, which I shall return to in Sect. 3.1.

To summarize, although people exchange arguments in the ongoing present, rhetorical argumentation aims at the future, yet draws on the past. Given the foundational role of emotions in decision making (Damasio 1994; Barrett 2017), we ought to also ask how emotion and argumentation are related.

2.2 Emotion in Argumentation

When time is limited and outcomes are contingent on decisions, emotions affect decision making (Pfau 2007), but such decision making is therefore not irrational. A key assumption is that reasonable grounds for an emotion can exist, so emotion can hence function as a legitimate reason for action (Greenspan 2004; Nussbaum 2015).

Emotions are “adaptive responses to the demands of the environment” (Elfenbein 2007, p. 316), and since antiquity such responses have figured in reasoning about actions because “emotions are all those feelings that so change men as to affect their judgements, and are accompanied by pleasure and pain” (Aristotle 2005, 1378a20). Speakers may argumentatively describe and construe such environmental demands as establishing a connection between the situation, the audience’s values, and the need to react to those values. To assess a situation as “good” or “bad” and hence worth approaching (pleasure) or avoiding (pain), an audience must have a system of values that provide reasons to desire and act in ways that achieve the goals or avoid the threats corresponding with those values (Macagno and Walton 2014, p. 65).

The inclusion of emotion in decision making is a source of long-standing dispute between rhetoric and ethics, because emotions can indeed prompt one to act with affect without considering the ramifications. The challenge is to distinguish well-grounded emotional appeals from manipulative trickery. As Villadsen aptly noted:

Persuasion may as well be used to inflame passions and cloud judgment as it may speak to reason and justice. With rhetoric there is always the threat of deterioration into deception and manipulation, but it is accompanied with the possibility of insisting on sound reasoning and relevant emotional and moral appeals. (Villadsen 2016, p. 48).

As emotions and values are necessary and unavoidable in rhetorical argumentation about practical choice, below I describe how the rhetorical tradition has conceptualized appeals to emotion (pathos).

Although Aristotle underlined that the speaker should put “the audience into a certain frame of mind” (2005, 1356a2), several scholars (Lee 1939; Brinton 1988b; Micheli 2010; Welzel and Tindale 2012) have pointed out his telling vagueness on exactly how a speaker stirs an audience’s emotions. However, as Brinton explained: “Generally by pathe Aristotle means (in the Rhetoric at least) feelings which influence human judgment or decision making and which are accompanied by pleasure or pain” (1988b, p. 208). Yet, when a speaker presents an argument capable of stirring, say, confidence within an audience (confidence, according to Aristotle, being the opposite of fear), but uses factual grounds to do so, logos and pathos seem difficult to separate. Simply put, “logos and pathos interact in that emotional appeals are generally built on a rational foundation; conversely, logical appeals generally have an emotional component” (Waddell 1990, p. 383). This type of interaction echoes another ancient scholar, namely Quintilian and his advice on making facts come alive before the eyes of an audience in order for them to ‘feel’ their relevance to a given case (see also Katula 2003, p. 9):

It is a great gift to be able to set forth the facts on which we are speaking clearly and vividly. For oratory fails of its full effect, and does not assert itself as it should, if its appeal is merely to the hearing, and if the judge merely feels that the facts on which he has to give his decision are being narrated to him, and not displayed in their living truth to the eyes of the mind. (Quintilian 1922, p. 245).

Brinton labeled such interaction of logos and pathos a pathotic argument, understood here as a “drawing of attention to reasonable grounds for the passion or emotion or sentiment in question.” (Brinton 1988a, p. 79). Hence, a pathotic argument includes a dimension of reason-giving for why a certain emotion (or combination of emotions) is appropriate, and these reasons allow one to examine emotion as lending an argument acceptability, relevance, and adequacy (Gilbert 2004).

Still, emotions have several functions in argumentative contexts (Carozza 2007) and a variety of normative roles. The dominant view within argumentation and logic has seen appeals to emotion as fallacies. Take, for instance, fear appeals that impose a threat on an audience and function as an argumentum ad baculum (Walton 1996). However, as Govier (2010), O’Keefe (2012) and Walton (1992, 2013) have all argued, appeals to emotion such as fear are not necessarily fallacious and are thus not per se unreasonable, because they “invoke consequences of an action as a basis for justifying performing or not performing that action” (O’Keefe 2012, p. 27).

According to Micheli (2010), in a “traditional” view emotions function as adjuvants to argumentation, meaning that speakers can appeal to emotions to support a conclusion and thereby promote a judgment, decision, and potentially action. In the convergence between judgment and emotion, I should underline, both are equally important. Emotions affect people’s cognitive judgments, as Aristotle recognized, for “when they feel friendly to the man who comes before them for judgement, they regard him as having done little wrong, if any; when they feel hostile, they take the opposite view” (Aristotle 2005, 1378a35). However, cognition can also affect emotion, because the emotions that affect decisions arise from grounds pertaining to “the role of judgment in the formation of the passions” (Micheli 2010, p. 6).

This dynamic understanding, in which emotions have not only cognitive effects but also cognitive origins, provides an important bulwark for assessing emotions as legitimate reasons. For the present purposes, I focus on argumentation that enables an emotional experience to be rooted in the Aristotelian cognitive understanding of emotion (Morreall 1993, quoted in Pfau 2007). In relation to arguments, emotion is defined as a specific state of mind directed at others and based on the grounds on which the emotions arise and thereby lead to persuasion.Footnote 5

If the grounds for an emotion are reasonable, then such an emotion can also be a legitimate reason for judgment and action (Greenspan 2004). Because beliefs and cognition can both function as grounds for emotions and give rise to them, it can be helpful to distinguish between evoking and invoking emotion (Brinton 1988b). Evoking emotion is an appeal toward emotion, an endeavor to arouse that emotion in the audience and thus cause an action, but not per se to provide a reason for taking it, as in ‘reflex emotions’ defined as “fairly quick, automatic responses to events and information” (Jasper 2011, p. 287). Invoking emotion is an appeal to emotion that involves a reason on which to base an action, which is to say the speaker gives the audience a reason to feel a certain way on which it can act. In short, to invoke emotion reflects how reasoned emotion can prompt responsive action. As such, adhering to a cognitive theory of emotion enables one to view emotion as reasonable in the dual sense of its providing reasons and being grounded in reasons. Having described the roles of temporality and emotion in argumentation let me unfold my main argument.

3 The Temporality of Emotion in Argumentation

Argumentation affects action via appeals that invoke emotion in order to translate the distant past and the anticipated future into the situated present. Such appeals function more than simply persuasively when a speaker appeals to a specific emotion, for an argument that succeeds in invoking an emotional focus can impel an audience to commit to action because of the expected consequences vis-à-vis past experiences (Walto 2002). As such, an argument has import to those making the decisions, thus motivating them to take action (Helm 2009). For example, to invoke patience persuasively, one must illustrate—that is, provide reasons in support of—that an impending mission is of a magnitude requiring a long, sustained effort, yet is both possible and worthwhile—and, hence, merits patience.

The temporality of appeals to emotion remains underexplored in argumentation studies. However, there are notable exceptions: Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca hinted at the emotional nature of temporality in argumentation when referring to “the insistent [appuyé] style, meant to provoke emotions, mainly aims to frame thought” (2020, p. 319). Macagno and Walton underlined that “emotions are both the result of past choices and past experiences, and evaluations of present and future state of affairs” (2014, p. 68), further underscoring the temporal dimension of emotions in relation to decision-making that in the case of for instance fear often involve “a choice between long-term safety and immediate gratification” (Walton 2013, p. 23). Mehlenbacher pointed to the underlying emotional nature of reasoning based on anticipation (prolepsis), in the sense that an anticipation of uncertain but imaginable outcomes “allows us to determine our current position in terms of desires, reason, and emotion for deliberation about prospective outcomes in terms of current actions or choices.” (2017, p. 246). Scott (2020) explored the “internal temporality” of argumentation, understood as the temporal unfolding of the involved actions associated with argumentation, such as speaking, listening, doubting, and judging (p. 33), although he only briefly tied temporality to emotion in argumentation. In fact, the following passage is the only place in Scott’s paper where he explicitly mentioned affect (neither pathos nor emotion appear in the paper):

The concept of adherence is essentially temporal—in the same way that something like a promise cannot be understood without a temporal reference to a possible future where it is either honoured or broken. With respect to adherence, this is to say that what a person is intellectually and affectively committed to at a given point in time cannot be reduced to any particular “present.” (Scott 2020, p. 31).

Indeed, adherence depends on both intellect and affect. Moreover, as should be evident by now, a logos of the passion and a passion of the logos converge (Waddell 1990). The notion of adherence, which Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca (1969, p. 1) stressed as fundamental in rhetorical argumentation, is highly relevant in a decision-making context of uncertainty. To adhere to a proposal—say, deciding to keep physical contact to a minimum—is to accept intellectually and affectively that the grounds on which the proposal rests are sufficiently convincing at the time the proposal is made, its building on existing knowledge and experience. By drawing on the past and imagining the future to inform the present in which a decision takes place, the temporality of argumentation gives presence to this moment, but how can one fully grasp such a presence without considering emotions and their temporal orientations?

The rest of this section proceeds as follows: First, a synthesis of temporality and emotion shows how temporal orientations of emotions affect rhetorical argumentation. Second, a conceptual model provides two temporal mechanisms for invoking presence. Third, a brief analysis of the speech in which Mette Frederiksen announced the Danish lockdown illustrates how the model works and may aid future theorizing of the temporality of decisive emotion.

3.1 The Temporality of Decisive Emotion

Emotions are “energy for action” (Plantin 1998; in Cigada 2006), and decisions made under uncertainty require a willingness to act on arguments despite a lack of sufficient data. As such, the temporality of argumentation touches upon the ontological duality of rhetoric (Bitzer 1968; Vatz 1973). When a speaker discursively makes the present moment appear to be the right moment in which to act, she draws on the mutual interconnectivity of the past and the future (Miller 1994). To make a decision in the present that will affect the future is to argue why the very targets to which people react with emotion warrant attention and action (Helm 2009, p. 250).

3.1.1 An Appeal to Emotion Appeals to Time

Before unfolding the temporal orientations of emotions, I would like to highlight why import is central to a theory of rhetorical argumentation. Something has import when it is worthy of attention and action, thus leading a person to be “reliably vigilant for circumstances affecting it favorably or adversely and be prepared to act on its behalf” (Helm 2009, p. 250). Feeling the motivational “pull” of emotions is an aspect of evaluating how to respond to surroundings that impose meaning on humans. One can therefore view appeals to emotion as appeals that invoke an emotional focus of import to decision makers and therefore resonate with the cognitive evaluations (appraisals) arising in the immanent situation and affecting the experience of emotion, which in turn motivates a person to decide and act. As Micheli wrote, such cognitive criteria of evaluation involved in experiencing emotion “offer interesting cues for the study of the discursive and emotionally-oriented constructs of events and situations [italics in the original]” (2020, p. 15). Of particular importance to a rhetorical understanding of emotion are the appraisals by which a person evaluates the environment and interaction with other persons (such as the speaker or the deliberating audience), motivational action tendencies, and the subjective experience of feelings (Moors et al. 2013, p. 119). Appraisals could encompass goal relevance (I must act to protect what I value), agency (my actions matter), certainty (amidst uncertainty, some signs give me a degree of faith), and coping potential (I have the means to withstand an enemy that initially frightened me).

These are all felt evaluations that undergird how it feels to be in a situation illuminating that the “discursive dimension of emotions appears with a particular clarity when emotion is in debate.” (Plantin 1999, p. 4). In other words, to feel an emotion like anger, a person will perceive negative events as being predictable, under their own human control (agency), and brought about by others, which may lead that person to engage in riskier behavior because she perceives little risk (Lerner and Keltner 2000). Here, agency comes to the fore in terms of whether audience members feel they can actually do something about the matter at hand. From a temporal perspective, human agency is

A temporally embedded process of social engagement, informed by the past (in its habitual aspect), but also oriented toward the future (as a capacity to imagine alternative possibilities) and toward the present (as a capacity to contextualize past habits and future projects within the contingencies of the moment). (Emirbayer and Mische 1998, p. 963).

Considering that rhetorical agency is defined as “the relative capacity of speech to intervene and affect change” (Hoff-Clausen 2018, p. 287), I would like to stress the link between the inherent temporality of agency and the role emotions play in rhetorical argumentation. If a speaker is to convince decision makers to decide and even act, and this commitment requires some assessment of agency, several emotions may arise and exist simultaneously. “In short, to feel one emotion is to be rationally committed to feeling a whole pattern of other emotions with a common focus” (Helm 2009, p. 251). Crucially, these patterns of emotions—arising from appraisals of the situation—stand in relation to the temporal orientation of the emotional focus, and the reasonableness of such practical emotional patterns depend exactly on their past (and expected) reason-giving capabilities:

Emotions serve to “mark” practically significant thoughts with bodily (and hence affective) indicators of past experience. According to an evaluative account, characteristic thoughts have come to be contents of emotion—and part of what identifies them as the types of emotion they are: fear, anger, joy, pride, and so forth. (Greenspan 2004, p. 208).

To summarize, appeals to emotion can invoke an emotional focus of import to decision makers, and when such import resonates with cognitive evaluations of the past, present, and future, emotion becomes timely and potentially reasonable.

3.1.2 Temporal Orientation of Emotion in Argumentation

When one includes the passing of time and events, the multidimensionality of emotion, which rarely exists independently, becomes part of rhetorical argumentation. For instance, a well-grounded fear of COVID-19 will tend to change as time progresses and events unfold, turning into relief or joy if people avoid becoming sick, disappointment or even grief if they do not, or anger if someone (un)knowingly endangers others, thus making all physical distancing efforts seem worthless. The temporal aspect of accumulating evidence will, then, help determine whether initial fear turns out to continue to be well-grounded as new information, experience and knowledge either harness the robustness of that emotion hereby underlining the rational (cognitive) structure of emotions (Micheli 2010, p. 6) or lead the rational actor to acknowledge that she did act in good faith but with time should abandon her continued commitment if there eventually is a lack of support for an anticipated future emotion. To continue along this path of commitment, one can view an initial well-grounded fear as a rational strategy of pre-commitment, prompting action, that (should) only hold as long as there are sufficient reasons in favor of supporting continued commitment:

In such cases [where wished for outcomes only materialize after a long investment period], the rational entrepreneur would not ignore sunk costs. But she would not be too highly swayed by them either, and would only base her calculations on commitment to realistic prospects of future success or failure, judged by practical reasoning. (Walton 2002, p. 499).

Emotions have temporal orientations enabling us to make a preliminary distinction between future- and past-oriented emotions in argumentation by drawing on Helm (2009), Baumgartner, Pieters, and Bagozzi (2008), and Cigada (2006). Notice that the above emotions are bound together by a common focus of import to the people experiencing them. This binding allows one to view appeals to time as appeals to the interaction between past- and future-oriented emotions and how these make the present worthy of attention and action.

Helm (2009) discussed eight such emotions, distinguishing between positive and negative past and future orientations; for example, satisfaction has a positive past orientation, and fear a negative future one. In a study on emotive communication in the political aftermath of World War II, Cigada (2006) further distinguished between the near-past and distant-past positive (euphoric) and negative (dysphoric) emotions. She underlined that pride in a historic tradition of working to ensure freedom and human rights functions as a particular argument in favor of hope about a future political situation; for example, if we won our freedom in the past, we can re-win it. This perspective emphasizes the dual argumentative understanding of emotion as both providing reasons to support a conclusion and functioning as a conclusion (Micheli 2010). Emotions can draw their reasonableness from the re-presentation of shared past events––which function as cause for, say, pride––and from imagined future events, which in turn support a focus on the action proposed in the present.

However, future-oriented emotions are both anticipatory––that is, felt in the present––and anticipated, in other words, to be felt in the future (Baumgartner et al. 2008). Anticipatory emotions such as hope or fear arise in the present at the prospect of a desirable or undesirable future event, whereas anticipated emotions stem from an imagined sense of how experiencing certain emotions will feel once future events have occurred. From an argumentative perspective, both forms of emotions function to provide an affective component when the consequences of an action are rhetorically deployed as a justification for taking or not taking that action. The interplay between instilling beliefs about anticipated (future) emotions and arousing current anticipatory emotions revolves around both the prospects of the subsequent diminishment or fulfillment of those very emotions and the reasons why they arose or are expected to arise (O’Keefe 2012, p. 28).

The temporal orientations of and relation between emotions brings me to the importance of balancing competing emotions. Sheer terror, for example, can be paralyzing. Pfau (2007) provided an elegant account of how fear and courage interact in what he labels “civic fear”, or fear that leads one to deliberate on, recognize, and ultimately respond to or confront contingent events that decision makers find reasons to deem worthy of fear. Similarly, Mehlenbacher’s account of the practical inference linking anticipated (proleptic) future outcomes and present action underlines that the issue at stake has to be proximal, have implications to the lives of the decision makers, in addition to “uncertain but imaginable outcomes.” (2017, p. 246). When those conditions are established, first, the speaker must be able to portray a dangerous target as a spatially and/or temporally proximate threat to decision makers, for if it will have no apparent impact on their well-being, no action is required. Second, and equally important, one must convey that the object of fear is contingent rather than inevitable, to ensure that decision makers believe that taking action could enable them to avert the threat that constitutes their fear. Third, the speaker must encourage decision makers to believe that they are, in fact, capable of taking worthwhile action.

In summary, emotions have temporal orientations and become interwoven as time unfolds. In other words, they do not exist independently of each other, but depend on their temporality and the appraisals with which speakers situate emotions in moments of time. For instance, a person experiencing fear in the present might soon experience the past-oriented emotion of relief if the source of fear proved not to inflict the anticipated pain (Clore and Ortony 2000).

3.2 Model: Affecting Argumentative Action

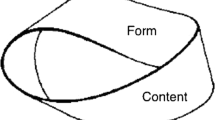

Building on the idea that emotions have temporal orientations as described above, a threefold pathotic argument outlines how a speaker must present her specific reasons for a decision in a way that convinces an audience to make that decision. The argument must therefore express (i) the exigence that a decision is necessary, (ii) the contingency of the decision, and (iii) the confidence to act. The pathotic argument enables us to present the following conceptualization of temporality and emotion in rhetorical argumentation (see Fig. 1):

In the following, I explain the concepts and mechanisms of the model. Argumentatively, the model reflects two interacting practical inferences (Walton 2006, p. 300) entailing (a minimum of) two temporally linked scenarios. I build on Mehlenbacher’s suggestion to distinguish between “prolepsis-with-negative-future and prolepsis-with-positive-future” (2017, p. 246), and therefore distinguish between two scenarios (broadly depicted as positive or negative, although I also acknowledge that this distinction may not hold when being exposed to empirical scrutiny and complex causal chains) that follow from either making a decision or continuing with the status-quo (in-decision). Nonetheless, for conceptual purposes, one scenario involves a future goal, G (worth achieving), which the audience can help realize if making the present proposed decision, D. The goal, G, reflects positive future-oriented emotions. The other scenario involves a goal, G’, deemed worth avoiding, which maintaining the status quo––an in-decision, D’––will most likely lead to (hence, the negative emotions). In both scenarios, experiences and choices from the past influence the emotions experienced in the present (Macagno and Walton 2014, p. 68) and inform the two intertemporal mechanisms of retrospective forecasting, which establishes a past–future–present link, and prospective remembering, which establishes a future-past-present link. Although Fig. 1 only depicts retrospective forecasting as negative and prospective remembering as positive, both mechanisms can rely on positive and negative valences as well as interact; that is, (reasonable) fear of negative future goals (G’) can lead to a decision (D), which eventually leads to positive future outcomes (G) exactly because of that decision.

Epistemic and practical uncertainty mean that the inference linking a present decision with a future goal will never be conclusive. The inference is quasi-logical (Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca 1969, p. 193), and adherence depends on whether the audience accepts the temporal interval between decision and consequence, that is, “the indeterminate wedge between cause and effect” (Bolduc and Frank 2010, p. 313). Even in cases where the consequences are near-certain, or what Mehlenbacher refers to as Prolepsis as future anteriority, an argument that anticipates and establishes a future fact (2017, p. 244), incommensurable values still guide decisions (Kock 2017, p. 68). Hence, the model seeks to illustrate how a speaker might use experiences and choices and thus accumulated knowledge of the past (EC/EC’) to inspire confidence in making a decision (D) in the present by invoking futures worth achieving (G) and/or avoiding (G’), all as part of the process of making those very outcomes contingent on the advocated decisions. The concepts of the rhetorical situation (Bitzer 1968; Vatz 1973) and Pfau’s (2007) “civic fear” framework for providing a constructive way of urging an audience to deliberate and take action guide the following conceptualization.

3.2.1 Exigence or the Need to Make a Decision

First, the speaker must diagnose the current situation as one requiring a decision. In situations characterized by high uncertainty, the existing data might dictate that inertia is the only “logical” choice, as nothing in the existing circumstances warrants change (Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca 1969, p. 106). Yet, the speaker is convinced that action and thus a deviation from the known path are required. In rhetorical terms such a need to act presents an exigence defined as an “imperfection marked by urgency; it is a defect, an obstacle, something waiting to be done, a thing which is other than it should be” (Bitzer 1968, p. 6). However, both situation and discourse may constitute such urgency (Vatz 1973; Leff and Utley 2004), especially if a speaker encourages present decisions whose consequences remain to be seen––economic reform policies, for example.

Therefore, the question remains; how does a speaker “prove” a specific action is necessary, let alone argue in favor of taking it, when she lacks hard evidence? Although uncertainty prevents her from making reliable predictions, affect is based on predictions from existing knowledge and past experience (Barrett 2017, p. 78) and on the projection of scenarios revolving around futures worth avoiding or approaching. Since convincing an audience that departing from the status quo is worthwhile, or at least marginally better than inertia, the speaker may diagnose the ongoing present as worthy of action by describing how maintaining the status quo––which naturally stems from the past overlapping with the present––can lead to dismal futures worth avoiding (G’). Like loss-framing, such a diagnosis emphasizes the negative consequences of noncompliance (O’Keefe 2013, p. 123). Similarly, the speaker may emphasize how taking steps towards better futures worth attaining (G) depends on making this decision. Such depictions may then lead to appraisals of goal relevance, including concerns for the well-being of the decision maker, thus prompting experiences of emotions such as hope, fear, and anger (Moors et al. 2013). A key aspect is how a speaker then credibly gives the future presence.

3.2.1.1 Retrospective Forecasting

I suggest that an argument by example works by invoking a known recent past, which then functions as an analogy of an anticipated near future worth either avoiding or approaching. Plantin argued that an analogy can help construct various types of feelings rhetorically-argumentatively and thus transfer emotions from the past to the present or an anticipated future because the analogous situations appear similar and within close proximity temporally and/or spatially (1999, p. 11–12). Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca distinguished between three approaches taken by a speaker seeking to establish a conclusion through a particular case: argument by example, illustration, and model/anti-model (1969, p. 350). Illustration is intended to increase adherence to a well-accepted rule, whereas example is aimed to establish a rule, temporally working by drawing on a particular case sufficiently probable to be one of general principle and thus helpful in avoiding or achieving future outcomes in the present case. I suggest labeling this mechanism retrospective forecasting, as it allows a speaker to give presence to what people in the invoked example did in a comparable case, but with the knowledge that currently exists in the situated present. Accordingly, such cases allow for both imitation and avoidance, thus warranting appeals to positive and negative consequences, respectively (Walton 2006, p. 106).

When we view an argument by example through a lens of retrospective forecasting, it is worth mentioning Quintilian’s notion of ‘vivid illustration’. Especially, such illustrative representations may function persuasively because of both their appeal to the imagination and ability to make a ‘transference of time’: “Nor is it only past or present actions which we may imagine: we may equally well present a picture of what is likely to happen or might have happened.” (1922, p. 399). In emphasizing the imaginative (and hence temporal) aspect of vivid illustrations, Quintilian underlined the interaction between facts and how a decision maker (judge) feels when assessing them hereby mirroring the ongoing convergence between cognition and emotion that I have emphasized throughout this paper.

Such vivid illustrations enable a decision maker to “imagine to himself other details that the orator does not describe” (Quintilian 1922, p. 247) but equally important, in relation to the concept of retrospective forecasting, I suggest that the vivid projection of future (imagined) outcomes and goals, whether worth avoiding or approaching, draws its presence from existing cases; the more recent and more familiar, the greater impact. Such a transference of time may only provide answers about decision outcomes by virtue of being temporally situated in the crux between the past and the ongoing present, that is, by being temporally compared to the situated present in which a decision is to be made. Examples give credibility to an inherent claim about a future projection made by appraising aspects of certainty even though logical demonstration is futile. This might sound paradoxical when it comes to dealing with decision making under uncertainty. However, there is a point: if a speaker projects a future worth avoiding, but the scenario seems unconnected to existing phenomena and thus unrealistic to the audience, the credibility decreases, and the projection may cease to function as a vivid (and hence credible) future scenario worth avoiding. This is the fate of so-called empty threats, not only because the threatened consequences might not come about, but also because the causal mechanism appears either completely unlikely or is unknown to the audience.

In sum, the first dimension is to argue that a decision is necessary. To do so, I propose, a speaker must show how the exigence demanding a decision is temporally close, as in an imminent threat or a passing opportunity. The next task is to show the audience that outcomes are contingent on the proposed decision––in other words, that its decisions matter.

3.2.2 Mediators of Change (Must) Have Agency

To show the above contingency, the speaker must present reasons why the decision makers are “mediators of change,” thus enabling them to acknowledge and accept that they possess the agency to actually affect the situation. Humans only deliberate about things within their power to change (Pfau 2007, p. 227; Kock 2017, p. 35). Accordingly, if an audience has no belief of such power, it will have no reason to care, in which case the speaker runs the risk of unwittingly convincing the audience to be utterly indifferent (lethargy) or give up before it even starts (despair). The speaker has to instill an agentic belief in the audience that it can cope and make a difference that leaves open an avenue of hope (Nussbaum 2018, p. 206).

3.2.3 Prospective Remembering

Another mechanism included in the model is the use of anticipated emotion to support the perception of the agency needed to make decisions in the present. I call this prospective remembering, which entails how it feels to be a person imagining herself situated in the future and looking back at the present in which she is to make her decision.

In general, decisions function as attempts to achieve positive future feelings, such as pride, and avoid negative emotions, such as guilt and regret (Lerner et al. 2015). Therefore, the anticipation of an emotion like regret can provide a reason to eschew excessive risk-taking. Notably, anticipated emotion does not appear to function independently of anticipatory emotions like fear and hope, just as the re-presentation of a past-oriented emotion like pride may support a presently experienced anticipatory emotion of hope (Cigada 2006), which in turn enables one to anticipate a future emotion of relief at overcoming a burdensome challenge.

Acting now in order to avoid feeling regret in the future can be a rational decision; that is, committing in the present to achieve or avoid the anticipated emotion related to future outcomes can indeed be rational. Although traditional economics textbooks have viewed sunk cost as a fallacy, the fallacious nature depends on whether one views rationality as utilitarian (cost–benefit) or deontological (commitment), leading to two distinct views of decision making; respectively a cost–benefit model and a model of practical reasoning and commitment (Walton 2002, p. 492). In short, if an actor bases a decision and action on a central personal principle (e.g. honesty), that act has value in and of itself regardless of a calculation of its consequences on a cost benefit scale because it helps her reason and navigate practical uncertainty “where exact calculation of costs and benefits is not possible, or would not be realistic.” (Walton 2002, p. 494). In relation to the current conceptualization of a temporality of affecting argumentative action, Walton’s point that precommitment can be a rational strategy (2002, p. 495) is helpful because it helps bridge understandings of practical reasoning as a process involving sunks costs (in the past) and appeals to anticipatory and anticipated (future) emotions such as pity and fear (Walton 1997, 2013). To be precise, emotions do not exist independent of the passing of time, and appeals to emotion (such as fallacious fear-appeals that rely on misinterpreted or false premises) gain their persuasiveness from how they evolve in light of new knowledge and experience.

Although certainty is a key difference between anticipatory (uncertain) and anticipated (certain) emotions (Baumgartner et al. 2008), anticipatory emotions experienced in the present may indeed directly relate to decisions and a pre-factual imagination of future states in which anticipated emotions arise. When decision makers make assumptions about the future occurrence of desired or undesired events and anticipate emotions, they still base these forecasts on both uncertain data and the potential contingencies of their own decisions. As such, fear might arise when one faces a dangerous threat like COVID-19, and uncertainty means that no one knows precisely how to avert disaster without jeopardizing democratic freedom. At the same time, however, one experiences a wide array of anticipated emotions, such as relief and joy, if the fear-inducing threat is successfully eliminated, and regret and disappointment if not. Similarly, anticipated emotions can help one stick to long-term goals by, for example, imagining future emotions of accomplishment.

Nonetheless, as with the mechanism of retrospective forecasting, which achieves a presence by establishing a past–future–present link, an emotional mechanism of prospective remembering still needs presence to affect a decision and, to invoke presence, a speaker must appeal to the audience’s existing experiences (Tucker 2001). Therefore, prospective remembering also draws on the past, but in the reverse order, thus achieving presence by establishing a future-past-present link. A speaker must draw on existing experiences and values from the past to enable decision makers to imagine how it feels to regret a present failure to make a decision that could have precluded undesirable consequences.

3.2.4 Argumentative Action

Third, despite the constraints of a present situation, a belief in the contingencies of one’s decision is insufficient. As such, Pfau (2007, p. 224) applied the virtue of courage—which lies between the extremes of fear and confidence—to explain how an audience might move from being inclined to have sufficient confidence to actually making a decision. This movement from civic fear to contingency and a confidence to act on the arguments presented echoes Nussbaum’s (2018) point that faith must bolster hope to be worthwhile. She says that if we think “our efforts are a waste of time, we don’t embrace hope” (p. 214). The connection between hope and faith illuminates how faith relates not only to the emotion of hope, but also to aspects of confidence and processes of trust (Khodyakov 2007). Temporally, the dimension of faith is past-oriented, gathering its reasons from past events in order to qualify whether there is reason to believe in the advocated course of action.

Positive anticipatory emotions like hope rely on some degree of belief that one’s decision (D) might enable better outcomes (G) than if one refrained (D’) from engaging in a given activity involving a worse outcome (G’), all of which again reflects decision makers’ appraisals of agency and coping potential. Nussbaum wrote: “We need to believe that the good things we hope for have a realistic chance of being realized through the efforts of flawed human beings” (2018, p. 213).

Thus, the synthesis of temporality and emotion in argumentation that adheres to a suggested proposal in the present transcends the temporal constraints of uncertainty. Such a commitment arises both because emotions experienced in relation to past events are re-interpreted and because emotions that may arise at future events are re-imagined. Scott (2020) underlined how adherence exists because of its relation to the past and future:

On the side of the past, what we presently adhere to can be understood as a kind of personal precedent, as the past weighing on the present as a constraint on what we will consider to be argumentatively reasonable (from myself and from others). On the side of the future, we will find that adherence makes reference to a number of possible futures where, under certain conditions, we would be committed to acting in certain ways given our current configuration of value commitments. (Scott 2020, p. 31).

To this, I should add that such adherence depends on the present emotional experience, which stems from the negotiation of how emotion constitutes the willingness to decide under uncertainty.

3.3 COVID-19: It Is Better to Act Today Than Regret Tomorrow

I now use the conceptualized model to illustrate how Mette Frederiksen on March 11, 2020, portrayed two possible scenarios to show her reasoning in support of her proposal to the Danish population to practice physical distancing.

During her speech, Frederiksen introduced what became a familiar catchphrase of the Danish coronavirus response: “Now we must stand together by keeping a distance.” In this instance, a “principle of caution” underlays the main practical inference (Walton 2006, p. 300), in which the goal was to protect “the most vulnerable people in our society” (Frederiksen 2020a). She presented the action of physical distancing as the means of slowing the spread of the virus and thus realizing this goal. Indeed, she emphasized the need to take action today in order to avoid regret in the future:

It is better to act today than regret tomorrow. We must take action where it has an effect. Where the disease is spreading [...] Therefore, the authorities recommend that we shut down all unnecessary activity in those areas for a period. We are adopting a principle of caution.

While Frederiksen’s argument rests on acceptable scientific knowledge, four days after the March 11 press conference, she underlined that the decision to lock down much of Danish society was ultimately political: “If I have to wait for evidence for everything in handling the coronavirus, then I am certain we will be too late.” (Frederiksen 2020b). Although the science says that close physical contact spreads the disease, the consequences of mandating a societal lockdown to avoid such contact are far more political in the sense that “any action that promotes one good or value tends to counteract others” (Kock 2017, p. 58). Frederiksen stressed: “We must minimize activity as much as possible. But without bringing Denmark to a halt. We must not throw Denmark into an economic crisis” (2020a).

Using the developed argument model (Fig. 1), I can show how Frederiksen constructed two decisions: either citizens decide to follow and support the recommended proposal of physical distancing, D, leading to a desirable future state of flattening the curve, G, or they do not distance, D’, which will lead to an undesirable future state worth avoiding at almost any cost, G’. The movement from D to G appears consequential despite the uncertainty of a novel disease. Equally important from a temporal and emotional perspective, an allusion to the distant and recent past makes the consequences of deciding to show public spirit and comply with physical distancing more credible, while the argumentative force of the outlined consequences depends on the emotions they invoke (see Fig. 2):

In the following sections, I detail how Frederiksen sought to connect the threat that COVID-19 posed, while also instilling a degree of belief that following government guidelines could make a difference. As such, she established the threat as contingent and invoked an element of courage that spurred decisive readiness.

3.3.1 Exigence

Frederiksen sought to establish the danger of COVID-19 and demanded action at a time when global news stories abounded and the disease was becoming serious in Denmark, but as of March 11, any Dane infected with the virus had yet to die (Sundhedsstyrelsen 2020).

When I stood here yesterday, there were 157 Danes infected with corona. Today, we have 514. That is more than a tenfold increase since Monday, where it was 35. The coronavirus spreads extremely fast.

The rapid increase in cases supported Frederiksen’s claim that the disease was not only dangerous but also spreading swiftly through Danish society, bringing an inevitable future threat ever closer. Urgent action was required, with the accent on urgent.

At the press conference, Frederiksen used Italy as an argument by example, stressing what Denmark should avoid. The Italian example enabled her to use the temporal mechanism of retrospective forecasting by drawing on the known recent past as an analogy for an anticipated near future worth avoiding and therefore as a present reason for physical distancing. Interestingly, Frederiksen rebutted a potential objection that the Italy reference was a scare example, emphasizing its “reality.” In doing so, she defined a scare example as a “fancifully conceived future scenario,” stressing that in contrast to the recent past, Italy served as a real example, one that could warn a Danish audience of the possible future consequences of present inaction against COVID-19. In the week leading up to her March 11 press conference, the Italian government had placed several of its northern provinces under lockdown, and on March 11 the cumulative death toll in Italy reached 827 (Remuzzi and Remuzzi 2020). In this context, Italy served as a well-grounded example capable of warning and potentially scaring a Danish audience because Danes know the country and can thus more easily accept the comparison as relevant and worth avoiding.

3.3.2 Contingency

While the numbers of infected citizens and the speed with which the virus was spreading could indeed support the severity of the situation, the target deemed dangerous and therefore worthy of fear could not be so overwhelming as to cause people to believe that no matter what they did, the crisis would strike (Pfau 2007). Frederiksen tried to inspire confidence in the potential of action by emphasizing that citizens should act in the present instead of waiting and regretting their inaction, underlining that physical distancing is precisely the measure to hinder the virus in spreading.

Although regret is a past-oriented emotion, Frederiksen contrasted taking action now (present) with a prospective remembering of regret. Although regret may stem from both following non-beneficial advice and ignoring beneficial advice (Tzini and Jain 2018), Frederiksen’s appeal to act in order to prevent a future feeling of regret draws its argumentative force from the certainty of physical distancing vis-à-vis the uncertainty of inaction, thus leading to an anticipated regret of how it generally feels to ignore the certainty of beneficial advice. In sum, in this instance adherence depended on an inference stating that sacrificing present freedom was worthwhile to avoid a greater future loss, such as life itself. One can view Frederiksen as attempting to bridge the uncertainty of navigating a “situation that does not look like anything we have tried before” with the certainty of anticipated regret, as this quote illustrates: “But the alternative—not to do anything—would be far worse. I hope there will be an understanding for that. I am convinced that there will be.”

In addition to regret, Frederiksen emphasized the opportunity for agency that lay ahead and reinforced such statements by highlighting what was already taking place in the recent past and ongoing present:

We must help each other. Show strength—think about others. Especially about those who are vulnerable. I would like to thank everyone in our health sector for the great contribution you are making. Thank you for your contribution now. And thank you in advance for your contribution in the coming days, weeks, and months. I am going to tell it like is. It is going to be tough. This situation puts great demands on all of us.

By speaking directly to essential workers, who were far more exposed than other parts of the population that could work from home or had been sent home, Frederiksen acknowledged both the work taking place and what lay ahead.

3.3.3 Confidence to Act

Lastly, while decision makers (e.g., healthcare professionals) must acknowledge the unfolding of events as contingent on their own actions, one needs the confidence to act to avoid the paralysis of what could be labeled well-informed hopelessness. Despite the “extraordinary situation,” Frederiksen encouraged citizens to stand up for Danish values when it mattered, underlining the goals of acting with an eye to the common good: “Let us now show what we are capable of when it matters. The Danes are already at it. We are showing public spirit. That is what works.”

By emphasizing what was already taking place (drawing on the recent past and ongoing present), Frederiksen stressed that agency and coping potential (“a huge responsibility”) were possible if one transcended the future and past into the present. While “proving” the future is inherently impossible in argumentation (Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca 2020), adherence to a proposal of, say, physical distancing, as Frederiksen advocated, depends on whether there are any compelling reasons to believe the future worth achieving will be realized (Nussbaum 2018). Ongoing action from civil society, drawing on a legacy of public spirit, may well have increased the felt probability of success in protecting the weakest citizens, even though predictions for specific measures were unreliable.

To summarize, I have illustrated how Mette Frederiksen, sought to gain support for her proposal to maintain physical distancing as a means of stopping the spread of COVID-19. Above all emphasizing negative future consequences worth avoiding, she translated these futures into the present by drawing on both the recent past (the Italian experience and lack of decisiveness) as an argument by example and by addressing the need to act now in order to avoid a future feeling of regret.

4 Conclusion: Taking a Leap of Faith

On March 11 2020, the W.H.O. declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, and Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen told the Danish population that this would have serious ramifications in the near future. Globally, the consequences of the pandemic have varied greatly, in terms of both fatalities and restrictions on freedoms. Two pertinent questions concern, first, the speed with which different governments responded and, second, the reasoning government leaders of democratic societies applied to their preemptive proposals aimed at mitigating the yet unseen consequences.

To understand how such argumentation under uncertainty functions, this study has combined two strands of theorizing within the argumentation literature: temporality and emotion. Starting from the premise that rhetorical argumentation is practical reasoning about choice of action, I have argued that in situations of uncertainty argumentation affects action, such as decisions, via appeals that invoke emotion and thereby translate the distant past and future into the situated present. Building on a dynamic understanding of emotion as having not only cognitive effects but also cognitive origins, I have suggested a model of affecting argumentative action and identified two intertemporal mechanisms—retrospective forecasting and prospective remembering—as a means of explaining how the distinct temporality of emotion enables argumentative action. For instance, an argument by example functions persuasively in situations marked by high uncertainty through the emotional analogy it makes. This does not happen because an example provides full epistemic certainty about future consequences, but rather because it minimizes the gap between an epistemic waiting game for certainty and a prudential willingness to act incisively, thus allowing a decision maker to commit herself and take the leap of reasonable faith that is a defining characteristic of human choice.

Notes

Unless otherwise stated, I have translated all quotes. Where necessary, I explain the reason for using a specific word. In this case, Abildgaard used the Danish word “tryg,” which in this context translates as “trust”. “Tryg” stems from Old Norse, “tryggr,” and German “true,” underlining the etymological connection with trust (Den Danske Ordbog 2020). One could also translate “tryg” as confident, because confidence stems from the Latin confīdere, that is “to put trust in, have confidence in, be sure.” (Merriam-Webster 2020).

In line with a well-established distinction within emotion research, I rely on affect as an umbrella term covering mood and emotion, in which emotions are discrete and intense but short-lived experiences, and moods are longer, more diffuse experiences that lack an awareness of the eliciting stimulus (Elfenbein 2007).

In a recent special issue of Argumentation on time and place (Tindale 2020), emotions play an insignificant role despite their role in practical argumentation that focuses on the future (e.g. Walton 1992, 1996; Tindale 2018, chapter 8; Kock 2017). However, see Cigada (2006) for a valuable exception as well as Macagno and Walton (2014, p. 68) for a brief mention in addition to Walton’s work on emotional appeals in relation to traditional fallacies (1997, 2013).

It is worth noticing that it does not, under all circumstances, hold true that demonstrations are out of time. When scientists (or lay people, for that sake) compare two valid demonstrations for the same problem, the shorter one is preferred in general because of Hjelmslev’s empirical principle in scientific discourse, which should meet, in the order, self-consistency, exhaustiveness, and simplicity (Garvin 1954) and an application of the Maxim of Relation (relevance) (Grice 1989, p. 27). I thank one of the reviewers for highlighting these important language philosophical aspects to me.

References

Aristotle, Eugene Garver. 2005. Poetics and Rhetoric. New York: Barnes and Noble Classics.

Barrett, Lisa Feldman. 2017. How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain. London: MacMillan.

Baumgartner, Hans, Rik Pieters, and Richard P. Bagozzi. 2008. Future-Oriented Emotions: Conceptualization and Behavioral Effects. European Journal of Social Psychology 38 (4): 685–696. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.467.

Ben-Ze’ev, Aaron. 1995. Emotions and Argumentation. Informal Logic. https://doi.org/10.22329/il.v17i2.2407.

Bitzer, Lloyd F. 1968. The Rhetorical Situation. Philosophy & Rhetoric 1 (1): 1–14.

Bolduc, Michelle K., and David A. Frank. 2010. Chaïm Perelman and Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca’s ‘On Temporality as a Characteristic of Argumentation’: Commentary and Translation. Philosophy and Rhetoric 43 (4): 308–315. https://doi.org/10.1353/par.2010.0003.

Brinton, Alan. 1988a. Appeal to the Angry Emotions. Informal Logic 10 (2): 77–87. https://doi.org/10.22329/il.v10i2.2641.

Brinton, Alan. 1988b. Pathos and the “Appeal to Emotion”: An Aristotelian Analysis. History of Philosophy Quarterly 5 (3): 207–219.

Carozza, Linda. 2007. Dissent in the Midst of Emotional Territory. Informal Logic 27 (2): 197–210. https://doi.org/10.22329/il.v27i2.475.

Cigada, Sara. 2006. “Past-Oriented And Future-Oriented Emotions In Argumentation For Europe During The Fifties.” In Rozenberg Quarterly. http://rozenbergquarterly.com/issa-proceedings-2006-past-oriented-and-future-oriented-emotions-in-argumentation-for-europe-during-the-fifties.

Clore, Gerald L, and Andrew Ortony. 2000. “Cognition in Emotion: Always, Sometimes, or Never.” In Cognitive Neuroscience of Emotion, edited by Richard D. Lane and Lynn Nadel, 24–61. Series in Affective Science. New York: Oxford University Press.

Damasio, Antonio R. 1994. Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. New York: Putnam.

Den Danske Ordbog. 2020. Online Dictionary. s.v. “tryg,” accessed November 22, 2020, https://ordnet.dk/ddo/ordbog?aselect=tryg&query=tryg

Elfenbein, Hillary A. 2007. Emotion in Organizations: A Review and Theoretical Integration. The Academy of Management Annals 1 (1): 315–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/078559812.

Emirbayer, Mustafa, and Ann Mische. 1998. What Is Agency? American Journal of Sociology 103 (4): 962–1023.

Frederiksen, Mette. 2020a. “Pressemøde om COVID-19 den 11. marts 2020.” www.stm.dk/_p_14920.html.

Frederiksen, Mette.. 2020b. “Pressemøde den 15. marts 2020.” www.stm.dk/_p_14925.html.

Garvin, Paul L. 1954. ”Reviewed Work: Prolegomena to a Theory of Language by Louis Hjelmslev, Francis J. Whitfield.” Language 30(1): 69–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/410221.

Gilbert, Michael A. 2004. Emotion, Argumentation and Informal Logic. Informal Logic 24 (3): 245–264. https://doi.org/10.22329/il.v24i3.2147.

Govier, Trudy. 2010. A Practical Study of Argument, 7th ed. Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning.

Granqvist, Nina, and Robin Gustafsson. 2016. Temporal Institutional Work. Academy of Management Journal 59 (3): 1009–1035. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0416.

Greenspan, Patricia. 2004. “Practical Reasoning and Emotion.” In The Oxford Handbook of Rationality, edited by Alfred R. Mele and Piers Rawling, 206–21. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195145397.003.0011.

Grice, Paul H. 1989. Studies in the way of words. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Helm, Bennett W. 2009. Emotions as Evaluative Feelings. Emotion Review 1 (3): 248–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073909103593.

Hernes, Tor, and Majken Schultz. 2020. Translating the Distant into the Present: How Actors Address Distant Past and Future Events through Situated Activity. Organization Theory 1 (1): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/2631787719900999.

Hoff-Clausen, Elisabeth. 2018. “Rhetorical Agency: What Enables and Restrains the Power of Speech?” In The Handbook of Organizational Rhetoric and Communication, edited by Øyvind Ihlen and Robert L. Heath, 287–99. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119265771.ch20.

Ihlen, Øyvind., and Robert L. Heath, eds. 2018. The Handbook of Organizational Rhetoric and Communication. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Jasper, James M. 2011. Emotions and Social Movements: Twenty Years of Theory and Research. Annual Review of Sociology 37: 285–303.

Katula, Richard A. 2003. Quintilian on the Art of Emotional Appeal. Rhetoric Review 22 (1): 5–15.

Khodyakov, Dmitry. 2007. Trust as a Process: A Three-Dimensional Approach. Sociology 41 (1): 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038507072285.

Kock, Christian. 2017. Deliberative Rhetoric: Arguing about Doing, vol. 5. Windsor: University of Windsor.

Kock, Christian. 2020. Introduction: Rhetoricians on Argumentation. Argumentation 34: 287–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-019-09503-0.

Lee, Irving J. 1939. Some Conceptions of Emotional Appeal in Rhetorical Theory. Speech Monographs 6 (1): 66–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637753909374862.

Leff, Michael C., and Ebony A. Utley. 2004. Instrumental and Constitutive Rhetoric in Martin Luther King Jr’.s ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail.’ Rhetoric & Public Affairs 7 (1): 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1353/rap.2004.0026.

Lerner, Jennifer S., and Dacher Keltner. 2000. Beyond Valence: Toward a Model of Emotion-Specific Influences on Judgement and Choice. Cognition & Emotion 14 (4): 473–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999300402763.

Lerner, Jennifer S., Ye. Li, Piercarlo Valdesolo, and Karim S. Kassam. 2015. Emotion and Decision Making. Annual Review of Psychology 66 (1): 799–823. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115043.

Macagno, Fabrizio, and Douglas Walton. 2014. Emotive Language in Argumentation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Mehlenbacher, Ashley R. 2017. Rhetorical Figures as Argument Schemes - The Proleptic Suite. Argument & Computation 8: 233–252. https://doi.org/10.3233/AAC-170028.

Merriam-Webster. 2020. Online Dictionary. s.v. “confidence,” accessed November 22, 2020, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/confidence.

Micheli, Raphaël. 2010. Emotions as Objects of Argumentative Constructions. Argumentation 24 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-008-9120-0.

Miller, Carolyn R. 1994. Opportunity, Opportunism, and Progress: Kairos in the Rhetoric of Technology. Argumentation 8 (1): 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00710705.

Moors, Agnes, Phoebe C. Ellsworth, Klaus R. Scherer, and Nico H. Frijda. 2013. Appraisal Theories of Emotion: State of the Art and Future Development. Emotion Review 5 (2): 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073912468165.

Morreall, John. 1993. Fear without Belief. Journal of Philosophy 90 (7): 359–366. https://doi.org/10.2307/2940792.

Nussbaum, Martha C. 2015. Political Emotions: Why Love Matters for Justice. Paperback. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Nussbaum, Martha C. 2018. The Monarchy of Fear. A Philosopher Looks at Our Political Crisis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

O’Keefe, Daniel J. 2012. Conviction, Persuasion, and Argumentation: Untangling the Ends and Means of Influence. Argumentation 26 (1): 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-011-9242-7.

O’Keefe, Daniel J. 2013. The Relative Persuasiveness of Different Forms of Arguments-from-Consequences: A Review and Integration. Annals of the International Communication Association 36 (1): 109–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2013.11679128.

OECD. 2020. “Global Economy Faces a Tightrope Walk to Recovery.” Economic Outlook. www.oecd.org/economy/global-economy-faces-a-tightrope-walk-to-recovery.htm.

Perelman, Chaim, and Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca. 1969. The New Rhetoric: A Treatise on Argumentation. Reprinted. Notre Dame, Ind: Univ. of Notre Dame Press.

Pfau, Michael W. 2007. Who’s Afraid of Fear Appeals? Contingency, Courage, and Deliberation in Rhetorical Theory and Practice. Philosophy & Rhetoric 40 (2): 216–237.

Plantin, Cristian. 1998. Les raisons des émotions. In Forms of Argumentative Discourse, edited by Marina Bondi, 3–50. Bologna: CLUEB.

Plantin, Christian. 1999. “Arguing emotions.” In Proceedings of the fourth international conference of the international society for the study of argumentation, ed. Frans van Eemeren et al., 631–638. Amsterdam: SicSat. http://www.icar.cnrs.fr/pageperso/cplantin/publications.htm

Quintilian. 1922. Institutio Oratorio. With An English Translation. Harold Edgeworth Butler. Cambridge. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Quintilian/Institutio_Oratoria

Remuzzi, Andrea, and Giuseppe Remuzzi. 2020. COVID-19 and Italy: what next? The Lancet 395 (10231): 1225–1228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30627-9.

Roser, Max, Hannah Ritchie, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, and Joe Hasell. 2020. “Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus/country/italy.

Schultz, Majken, and Tor Hernes. 2013. A Temporal Perspective on Organizational Identity. Organization Science 24 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1110.0731.

Schulz, Rasmus B. 2020. “Professor roser Mette Frederiksen -og advarer om én ting.” Berlingske, March 22, 2020, sec. 1. https://www.berlingske.dk/politik/mette-frederiksens-historiske-taler-imponerer-professor-i-retorik-men-en

Scott, Blake D. 2020. Argumentation and the Challenge of Time: Perelman, Temporality, and the Future of Argument. Argumentation 34 (1): 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-019-09493-z.

Sundhedsstyrelsen. 2020. “Tal og overvågning af COVID-19.” www.sst.dk/da/corona/tal-og-overvaagning.

Tiedens, Larissa Z., and Susan Linton. 2001. Judgment under Emotional Certainty and Uncertainty: The Effects of Specific Emotions on Information Processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 81 (6): 973. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.6.973.

Tindale, Christopher William. 2018. The Philosophy of Argument and Audience Reception. Paperback. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tucker, Robert E. 2001. Figure, Ground and Presence: A Phenomenology of Meaning in Rhetoric. Quarterly Journal of Speech 87 (4): 396–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/00335630109384348.

Tzini, Konstantina, and Kriti Jain. 2018. The Role of Anticipated Regret in Advice Taking: Anticipated Regret and Advice Taking. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 31 (1): 74–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.2048.

Vatz, Richard E. 1973. The Myth of the Rhetorical Situation. Philosophy & Rhetoric 6 (3): 154–161.

Villadsen, Lisa S. 2016. “Propaedeutics to Action: Vernacular Rhetorical Citizenship–Reflections on and of the Work of Gerard A. Hauser.” In Gerard A. Hauser. Rhetorical Scholar of the Public Sphere, edited by Ronald C. Arnett, 47–63. Pennsylvania Scholar Series 8. Pittsburgh: Pennsylvania Communication Association.

Vohs, Kathleen D., Roy F. Baumeister, and George Loewenstein. 2007. Do Emotions Help or Hurt Decision Making?: A Hedgefoxian Perspective. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Waddell, Craig. 1990. The Role of Pathos in the Decision-making Process: A Study in the Rhetoric of Science Policy. Quarterly Journal of Speech 76 (4): 381–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/00335639009383932.

Walton, Douglas N. 1990. What Is Reasoning? What Is an Argument? The Journal of Philosophy 87 (8): 399. https://doi.org/10.2307/2026735.

Walton, Douglas N. 1992. The Place of Emotion in Argument. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Walton, Douglas N. 1996. Practical Reasoning and the Structure of Fear Appeal Arguments. Philosophy & Rhetoric 29 (4): 301–313.

Walton, Douglas N. 1997. Appeal to Pity: Argumentum ad Misericordiam. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.