Abstract

Women are important actors in smallholder farmer milk production. Therefore, female input in the dairy cooperatives is essential to dairy development in emerging economies. Within dairy value chains, however, their contributions are often not formally acknowledged or rewarded. This article contributes to filling this gap by adopting a multileveled institutional perspective to explore the case of dairy development in the Pangalengan mixed-sex dairy cooperative on West Java, Indonesia. The objective is to add evidence from the dairy development practice in Indonesia to the current agenda for gender and development as well as identify pathways for future research on dairy development that will help it do better in practice. Central to the exploration is a discussion of formal and informal institutions as part of the dynamics of the inequality regimes in dairy cooperatives. Evidence from dairy development practices in the Pangalengan cooperative shows, among others, distinct differences between the participation of male and female target groups in dairy development extension, as well as farm size- and resource-related trends in ‘masculinization’ and ‘feminization’ of the smallholder farmer household. The conclusions contribute to debates on more resilient, thus sustainable working relations in food chains, women’s empowerment, gender equality and social justice in agriculture as well as cooperative studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Women are important actors in smallholder farmer milk production. Therefore, female input in the dairy cooperatives is essential to dairy development in emerging economies. Within dairy value chains, however, their contributions are often not formally acknowledged or rewarded. This article contributes to filling this gap by adopting a multileveled institutional perspective to explore the case of dairy development in the KPBS Pangalengan mixed-sex dairy cooperative on West Java, Indonesia.

The Indonesian dairy market is attracting national and international attention. Its potential can only partly be exploited by local smallholder dairy farmers who collaborate in cooperative organizations that are still working on their professional development. The institutions that formally and informally structure the gender relations in these dairy cooperatives are explored in this article. The research question is what distinct micro-, meso- and macro-level institutional dynamics can be identified as interacting dimensions of inequality regimes. These inequality regimes refer to practices, processes, actions and meanings that result in oppressive structural categories affecting dairying women in contributing to dairy development (Acker 2006). The concept of inequality regimes focuses on formal and informal institutional and organizational levels as affecting the individual.Footnote 1 As will be discussed in the following, this integrated perspective on gender, the relational dynamics that socially construct a binary male–female differentiation as ‘a moving target’, can be considered a current approach that progresses from the well- known ideal of ‘gender mainstreaming’ (Laven and Pyburn 2015; Bock and Van der Burg 2017).

The article builds on a case study that was compiled as part of the LIQUID research programFootnote 2 at the KPBS Pangalengan dairy cooperative on West Java, Indonesia. The qualitative, case study-based approach this article takes does not claim to provide exhaustive descriptions or singular solutions to women’s empowerment issues as related to dairy development in cooperatives. Women’s empowerment is used to describe practices, policies and other enabling factors that increase women’s ability to access and benefit as stakeholders (members, employees, wives of member) of the dairy cooperative (Duguid and Weber 2016; Kabeer 1999). By making the connection between multiple levels of institutions to explore inequality regimes in the theoretical framework, practically, the objective of the case study is to both add evidence to dairy development practice in Indonesia and identify pathways for future research on more effective designs of dairy development that will help it do better in practice. Theoretically, it aims to contribute to debates on sustainable food chains, social equality and gender in agriculture as well as cooperative studies.

A cooperative is formally defined as an autonomous association of people united voluntarily to meet their economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically controlled business (International Labour Organization (ILO) 2002). It is assumed that cooperatives can serve as structures for development through education, resource distribution and savings and credit programs that support social equality (Majurin 2012). The assumption of a ‘cooperative advantage’ to result in the emancipation of rural populations and poverty reduction has been a driver in the Indonesian government’s support of cooperatives as part of economic and social development strategies. Moreover, working within a collective system is considered to have the potential to empower women, providing them with a support system, allowing own agency and opening up markets that they cannot reach as individual producers (International Cooperative Alliance (ICA) 2015; Worldbank 2012; Valdivia 2001). In return, women could have much to contribute to cooperatives as active community members that can provide new insights on pathways to emancipation and rural poverty reduction (Lecoutere 2017).

Research has shown women to be important actors in milk production and dairy development (Bock and Van der Burg 2017). On smallholder farms in West Java, effectively, women are taking care of the cows and milk production on a daily basis. Next to other ‘stay-at-home’ duties in agriculture, women are responsible for the household and perform family caring tasks. The male responsibility, when and if he is present, is mostly to collect feed and offer physical support to milking. On West Java, spouses often work as a ‘team’ in farming systems, with the children as an incidental labour force. Thus, women can be considered the most important actors in improving milk quality and quantity as their actions directly impact, among others, hygiene. It would make sense to direct extension services aimed at dairy development at women. However, “while several interventions have been made to address this ‘gender’ bias in extension delivery, there continues to be a shortfall between the kind of support that is provided and the needs and demands of rural women.” (Jafry and Sulaiman 2013, p. 469).

This observation is not unique as, in many industrialized and non-industrialized countries, female contributions are not yet formally acknowledged or rewarded, especially within cooperatives (Nippierd and Holmgren 2002). In policies aimed at changing this situation, the empowerment of women in cooperatives is often treated as a static ‘destination’ or end goal, rather than a dynamic and ongoing process (Kabeer 1999). However, ‘empowering’ and ‘being empowered’ are not isolated acts but are embedded institutions at multiple levels of society as well as co-depend on the human capital accrued in, among others, social class and education (Batliwala 2007).

The value of explicitly and systematically obtaining female contributions seems underestimated as a necessary condition for the improvement of the dairy value chain (Tesfay and Tadele 2013). Since the important qualitative contributions by White (1984, 2016) on agricultural change and gender relations on Java, this has become visible in the lack of practical attention to this issue, as well as in the gap in scientific research. It is evident therefore, to work at our understanding of the dynamics of dairy development from an institutional perspective as these seem to affect the inclusion of female dairy farmers.Footnote 3

Research on the process of upgrading the dairy value chain has shown that:

-

Female dairy farmers are distinct producers within the family framework. Identifying their unique contributions allows for a completer view of the dairy value chain (Perrons 2005).

-

To optimize and innovate in the dairy sector it is important to include women as sources of information, planners and entrepreneurs (Bock and Van der Burg 2017).

-

Processes of decision making improve when female farmers are included. They add to the diversity of voices that make a cooperative organization. Considering the effect of female representation in governance structures, mainstreaming their participation at every level of the dairy cooperative can be recommended (Agarwal 2003; Kabeer 2005).

The exploration acknowledges the interwoven nature of among others, gender, class and education at the micro, meso and macro level.Footnote 4 The objective is to add evidence from dairy development practice in Indonesia to the current agenda for gender and development as well as identify pathways for future research on dairy development that will help it do better in practice.

The strength of the institutional perspective that the central concept of inequality regimes offers, is that it does not limit us to one narrative or one ‘truth’, but enables a discussion of the countervailing forces that are present in everyday reality. Considering the diversity of equilibria that can govern these forces in everyday reality, the research design is based on ethnographic-inspired qualitative methods. In the study a multileveled contextualization is the defining characteristic of the ethnographic alternating “Extreme close-ups that show detail [..] with ‘wide-angle’ or ‘long shots’ that show panoramic views” (Ybema et al. 2009, p. 7).

In the next section, the use of a range of qualitative methods for data collection and analysis is described in more detail. The adoption of several distinct methods makes visible the triangulation and compilation of information from the literature, interviews and observations that have brought forward the multiple layers of the case at hand. Presenting layer upon layer, first, formal and informal Indonesian institutions that affect the dairy value chain from the national down to the cooperative level are presented. This provides the context for the case description of the collaboration on dairy developments at KPBS Pangalengan. In the “Discussion” section, findings are related back to theory and, finally, conclusions are presented as well as pathways for future research.

Methods

While regulative formal institutions can be studied in literature, documents, archives and reports, insights in the normative informal rules that influence human interactions require ethnography-inspired methods. Ethnographic methods are based on the assumption that observations, interviews and thick descriptions of events, phenomena and the study of ‘people in places’ allow for an understanding of peoples’ choices, perceptions and, in this case, their interpretations of the institutions at play (Zussman 2004). This is important as farmer learning and technology can be both challenged and facilitated by shared norms and values in distinct cultures (Palis 2006).

In this exploratory study, we used a mixed methods approach in data collection allowing for the triangulation of data to improve the validity of the findings. The study begins with the systematic collection of secondary data from the following:

-

Recent scientific publications on research, theoretic literature, archival sources and statistical data; and

-

Reports and articles based on research at the KPBS and other cooperative organizations on West Java.

In preparation for and during three visits to West and East Java, Indonesia in 2016 and 2017, data were collected by:

-

Semi-structured interviews with academic, practitioners and governmental experts in The Netherlands and Indonesia;

-

Observations during meetings of the dairy development support team of Frisian Flag Indonesia (FFI) and Agriterra Indonesia;

-

Observations made while accompanying the KPBS/FFI dairy development officer during visits to the cooperative and several milk collection points;

-

Semi-structured interviews at two FFI selected exemplary medium size dairy farmer households in Pangalengan.

This data collection focused on the LIQUID sub research question: ‘Considering the inclusion of women, what are important institutional facilitators and constraints to dairy development extension services aimed at milk quality improvement by Thai smallholder dairy farmers in cooperatives as compared to Indonesian smallholders?’ Extension is the focus of the LIQUID sub research, understood as an instrument to implement dairy development objectives.

See the “Appendix” for an anonymized overview of the participants. Findings were either obtained in English language or Dutch language and translated by the author, or translated from Indonesian to English by the accompanying KPBS/FFI dairy development officer.

The KPBS cooperative is supported by the FFI dairy development program and the Agriterra agribusiness advisory services. The FFI dairy development programme states its objective to develop better milk quality, better income and better livelihoods for smallholder dairy households (Royal FrieslandCampina 2017). Access to the KPBS cooperative was provided by RFC/FFI and Agriterra.

Qualitative data-analysis was performed on the integrated body of the field notes from observations and interview reports with Atlas.ti software. Taking into account the history, culture and the socio-political and biophysical contexts that institutions and power-relations are embedded in, relevant literature was included in the analysis in an iterative process of manual theme identification and assessments of the relationships between themes and findings.

Institutional contexts

Macro: laws, rules and regulations affecting dairy cooperatives

The Indonesian government states to commit itself to strategic plans aiming at equitable and inclusive “Pro-poor, pro-job .... and pro-environmental” growth (ADB 2012, p. 27). These plans include ambitions for extensive local dairy production and growth of the dairy sector in an inclusive way. Despite this statement of good intentions, overall the weak enforcement of controlling institutions, the fragility of policies, and rampant corruption provide strong societal barriers to the active uptake of formal policies regarding dairy development and professional support (Sharma 2013).

Since the 1970s, dairy cooperatives are central to the Indonesian government’s drive for dairy value chain improvement (Sulastri and Maharjan 2002). Dairy farmer cooperatives are most directly subject to laws, rules and regulations as formulated and implemented by three ministries: the Ministry of Cooperatives, the Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministry of Industry.

Additionally, the semi-governmental cooperatives’ umbrella organization, the Union of Indonesian Dairy Cooperatives (Gabungan Koperasi Susu Indonesia or GKSI) is focused on the professionalization of the cooperative organization. The GKSI has a strong national and regional presence with board members from the larger local cooperatives. The support of the GKSI has been instrumental for the development of dairy departments at the community-based cooperatives (Koperasi Unit Desa or KUD) as well as the professionalization of dedicated Milk KUD. The GKSI provides input, also, for the cooperatives’ individual dairy development programs and the extension practices by the KUD’s own dairy development teams.

In practice, the Ministries’ national and regional activities vary in effectiveness. As mentioned in interviews on the subject:

The most important one [Institution] impacting on the situation with the cooperatives is the first Cooperative Law [Regulation 25/1992] that is unclear. In 2000 they started on a new one that was instated in 2002 [Regulation 17/2002]. But it was a bad law, very opaque. People complained and it was cancelled, but it was not replaced. So the old law is still working and it is dysfunctional (Participant 11, Interview 23-12-2016, Bogor).

This cooperative expert, who conducted extensive research on cooperative organizations, representing general expertise on cooperative law in Indonesia, considers the most important cooperative law to be ‘outdated’ and ‘dysfunctional’.

The Ministry of Agriculture establishes contacts [to work on dairy development] with farmers through the cooperatives, but they are not in charge of the cooperatives, this is the Ministry of Cooperatives. The rules and policies issued by these two ministries are not coordinated and they often counteract each other in practice (Participant 4, 22-3-2017, Wageningen).

The cooperative organizations are held accountable by several ministries: (i) as entry points to reach the smallholder farmers (Ministry of Agriculture); (ii) as agribusiness organizations that contribute to the Indonesian economy (Ministry of Industry), and; (iii) as rural organizations that could function as instruments and intermediaries for the education and poverty reduction of farmer families (Ministry of Cooperatives). In practice, in efforts to follow the rules and regulations of different governmental organizations, multiple, sometimes competing, goals are pursued leading to organizational inefficiency.

Government does not do enough about dairy improvement and building the dairy sector. They say they do, but they don’t. Scarcely, resources are going to cattle (Participant 1, 10-12-2016, Bandung).

The government is informed but not active. We need proof of their real commitment and enforcement of governance. This needs to be the future of dairy farming (Participant 8, 8-12-2016, Bandung).

These quotes are related to the governmental capacity and the priority given (financially and politically) to support the cooperatives. The perception of a majority of the participants (nine out the 11 that answered this question) is that the Indonesian government does not really invest in the dairy industry. Support, so far, has remained shallow. In contrast, the GKSI is perceived as an important platform and resource that is distinctly independent and does provide much needed support, as a private sector dairy development officer phrases it: “The GKSI is seen as independent. They are representing the interests of the cooperatives and not those of the government” (Participant 8, 8-12-2016, Bandung). This allows the GKSI to be an important broker between cooperatives as members of its board are also employed in cooperatives. Also, they can be a resource for the sharing of best practices as well as a knowledge platform to provide input to, among others, extension services and the adoption of innovations. “The people who make the regulations, they do not seem to know how it works. At the Ministry of Cooperatives there is a problem” (Participant 11, 22-3-2017, Bogor). Experts and dairy development officers are firm in their conclusions that there is a lack of capacity and knowledge on dairy production, smallholder farming as well as cooperative work with the policy makers, which, in practice, seems to further invalidate the already failing institutional framework the government has provided.

To meet the demand for livestock products, the Indonesian government has issued both new supportive regulations as well as deregulated some of the existing trade and livestock production and feed grains policies. Women’s empowerment and the ambition to include female smallholder farmers in the formal institutions that structure cooperative governance are not explicitly included in any of these actions.

Indonesian women stay behind men on several indicators of socioeconomic status relevant to women’s empowerment that are also at work in dairy development, such as land ownership and formal income levels (UNDP 2016). Other such national institutions are:

-

The 1974 Marriage Law that determines that a wife “Has the responsibility of taking care of the household to the best of her ability”. A husbands’ polygamy is authorized in case the woman does not fulfill the obligations of a wife (Robinson and Bessell 2002).

-

National laws that state that sexual and reproductive health services may only be given to legally married couples and require a husband’s consent (ADB 2012).

-

Islamic law that imposes restrictions on dress code, freedom of movement and access to public spaces (ADB 2012).

While action has not yet been observed, the Indonesian government has voiced ambitions to promote more equal gender relations. The Gender Equality and Justice Bill, which would change the marriage law, has languished in Parliament since its conception in 2010. The proposed bill covers 12 areas including citizenship, education, employment, health and marriage. Provisions include: equal rights for women and men to work in all sectors; equal pay for the same work; the right to determine the number and spacing of children; being able to choose husbands and wives without force, and; fair treatment before the law (Win 2014). In its formal institutionalization, the bill has been stalled by Islamists groups that object to the liberal freedoms allowed to women. It was sent back for reformulation in 2012. Given the evolving climate of religious extremism at all levels of society, however, it is doubtful whether it will be handed in again in the same form (Harsono 2014).

Meso: laws, rules and regulations

As governmental incentives are limited in their effectivity, cooperatives have turned to milk processors for support. The private sector has tried to fill the vacuum in dairy development. Commercial dairy development programs aimed to improve the quantity and quality of milk production are mostly run by international milk processors such as RFC based in The Netherland and Nestlé based in Switzerland, working through local subsidiaries such as FFI and PT Nestle Indonesia. Also, civil society organizations like Solidaridad are conducting projects in dairy cooperatives. Considering slow progress and incremental changes, however, the comments of an agricultural professor on the dairy sector merit some reflection.

We are not addressing the real issue. A lot of attention is given to governmental support and initiatives by private companies, as we depend on those. But this is not the real issue. The real issue is social inequality (Participant 1, 10-12-2016, Bandung).

His observation implies that social class, education and land ownership are important to our understanding of access to the cooperative resources that support dairy development. Findings in this study suggest that, in line with research findings in India and other countries, that Indonesian cooperatives also may be vulnerable to ‘elite capture’. Elite capture refers to the doubts that have arisen about the capacity of ‘collective action’ to effectively reach the poor households that poverty reduction strategies are aimed at, and, rather, benefit the ‘better-of’ farmers that already own land, have a relative larger number of cows and access to essential resources (Basu and Chakraborty 2008; Benson and Jafry 2013; Dohmwirth 2014).

In line with the legal, political and religious trends towards disempowerment that were identified above, formal institutional constraints to women’s empowerment in dairy development affecting cooperatives can be categorized with Nippierd (2002) as constraints related to property ownership, inheritance rights, control over land and membership rights.

In the description of the situation at KPBS Pangalengan, several implications of these formal constraints will be illustrated.

The 1998 regime change that led to a transformation of society from the Suharto dictatorship to more democratic models held the promise of social change (Robinson and Bessell 2002). Over the years since, however, the influence of the rise of the Islam and the renaissance of Indonesian traditions have gone a long way in neutralizing the government’s efforts to empower Indonesian women (Schaner and Das 2016). As a reverse effect, it has been observed that the ongoing attention to democratization and institutional change after the 1998 regime change have led to the formalization of farm responsibilities and attribute them to the (mostly male) head of the household. Until then, these responsibilities were often attributed to the females in a household (Blackwood 2008).

Meso: social communities and rules of behaviour

Inequality regimes in the Indonesian dairy sector and the policies aimed to neutralize them cannot escape being related to the growing influence of religious norms on policies and everyday life. These are normative barriers that Indonesian women face in their livelihood strategies and their daily household duties (Ford and Parker 2008).Footnote 5

Paradoxically, dairy farming is regarded as a low status profession for small size smallholder dairy households with less than five cows, and it is associated with higher status for those of medium to large size that possess more than ten cows (Nugraha 2010, p. 141). Social inequality thus seems to have institutionalized in mainstream perceptions of dairying as a profession.

The smallholder farmer dairy cattle business in Indonesia is mostly run as a secondary activity next to crop growing or small shop ownership, among other activities. Smallholders own a relatively low number of dairy cows that they may have acquired as a ‘gift’ from the government and try and exploit without further training or additional investment in professional equipment. In poorer regions, particularly in those without natural resources and land suitable for irrigation, livestock animals play an important role as ‘liquid assets’. They can provide a buffer against inflation and can be converted to cash when the need arises (Kustiari 2014). In governmental discourse the thought is engrained that ‘Everybody is a dairy farmer’.

In Indonesia, dairy farming is not a traditional way of life and drinking milk is not a part of the food culture. This has several consequences, but mentioned here should be that:

-

i.

There is no tradition of good farming practices including hygiene observations or quality feed provision

-

ii.

As most farmers do not drink milk, they have little awareness of the appropriate treatment of milk as a perishable product

At the household level, reasons for the lack of milk quantity and quality that require dairy development support can be found in the lack of priority, technology and knowledge of adequate dairy management as well as the lack of funding to upscale these activities. Also, problems are the difficulty of finding forage due to limited access to land as well as a low quality of feed. Countrywide, moreover, the necessary infrastructure to both deliver required inputs and bring products to processors are missing (Nugraha 2010).

Traditionally, female farmers have always played an active and responsible role in smallholder farmer agriculture as well as in the mobilization of local communities (International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) 1985; Najib 1986).

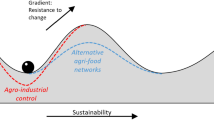

Micro: feminization-masculinization

Proceeding from the macro-level towards the micro-level, women used to be all but invisible in rural culture in many regions in Indonesia. After a period of relative acceptance of women’s mobilization in empowering organizations, including agricultural associations, under Sukarno, however, the violent take-over by Suharto in 1965 restricted women’s political participation. Womanhood, still, has evolved as modelled on the dominant discourse on women as “protectors of the moral and social order” as well as “good wives” and “mothers of the nation” that are to spend their time as caretaker and free labour source at home and remain invisible (Graham Davies 2005, pp. 239–241). Paradoxically, as research on migration, rural development and natural resources management has shown, the women who stay behind on the smallholder farm while their husbands are exercising these new powers, effectively become the main producers leading a trend of ‘feminization’ (Agarwal 2003; Kelkar 2007; Resurreccion and Elmhirst 2008). Thus the restriction of women’s mobility, which can be considered a barrier, becomes an enabler of their empowerment by having a direct say over resources and are not being held directly accountable to anyone in their choices for innovation and market access.

Paradoxically, as noted above, in parallel to informal ‘feminization’ from the bottom-up a process of formal ‘masculinization’ from the top-down is taking place. This ‘masculinization’ has resulted in a diminution of women’s traditional positions as informal accountants and bookkeepers in the smallholder farmer households. In past decades, farmer women often extended this function into the community and found community-based ways of working together in financial matters. Moreover, on Java credits and loans were often handled by women through small scale, autonomous and relatively informal rotating credit or savings and loan associations (Blackwood 2008). Currently, with the formalization of agricultural credits in cooperative banks, men have become the conduits of credit and the sole formal beneficiary authorized to sign for them. Furthermore, the male head of a household alone is allowed to arrange credits to invest in farming efforts and grow a larger size business. In this hierarchy, female farmers are rather treated as ‘labour resource’ or ‘employee’ than as the traditional ‘partner’ with, informally, a relatively equal status.

The KPBS Pangalengan dairy cooperative

Selected as one of the cooperatives with great potential and ambition to work on better milk production, since 2008 KPBS has been a supplier to Frisian Flag Indonesia (FFI, a subsidiary of RFC) and a receiver of technical support that FFI has delegated to Agriterra (a Dutch organization providing cooperatives with advice and training). The information in this case study is based on field visits with FFI/KPBS dairy development officers and complementary field interviews in 2016 and 2017. In addition, secondary information available at FFI and Agriterra was used.

Membership and gender

In 1969, with 600 members, the Koperasi Peternak Bandung Selatan (Cooperative of South Bandung Dairy Farmers or KPBS) Pangalengan cooperative was the first formal cooperative of Indonesia. Membership has varied considerably since. For instance, in 2012/2013 KPBS Pangalengan had 6873 members (including members actively supplying milk and non-active members) holding about 16,850 cows and producing 137,000 kilograms of raw milk per day. In 2014, after extensive culling of cows in the year before to profit from high beef prices, KPBS had 5551 members (active and non-active) that held only about 4000 cows.

The difference between Pangalengan and the other big good cooperative in Lembang is that, there, multiple members per household are allowed in. In Pangalengan only the head of the household can be a voting member. When you have multiple members, there are more opportunities for getting credit. Pangalengan now has [the] one man, one vote system (Participant 15, 20-12-2016, Pangalengan).

In Indonesia, cooperatives are free to regulate the membership as they see fit within the framework of general regulations. At KPBS, the structure is set up around solidarity and cow ownership. To be allowed to become a member, the farmer should possess one or more cows; be older than 17 years and have a stable to keep the cow(s). Since 2015, only one person per family can be a member as the ‘one-man-one-vote’ has been instated. The change was motivated with arguments of social equality that problematized the ‘old’ system of farm size-dependent voting rights in which a medium size dairy farm would have more influence than a small size dairy farm (Participant 8, 8-12-2016, Bandung).

Despite the gender blind nature of formal regulations at KPBS, in practice they seem to result in a male dominance in the access to the cooperative’s productive resources. This is due to the fact that the male membership holds voting rights (women cannot own land and only one member per household has access), only male candidates are eligible for credit facilities (it has to be the head of the household) as well as the election of mostly male leaders and representatives.

In 2012, the Agriterra organizational analysis report that was made as a baseline study states that, at the time, all dairy farmers in Pangalengan are members of the KPBS (Janszen and Veld 2012). See Table 1 for an overview of the membership per gender in 2010–2012.

Unfortunately, numbers are not available at the household level. It is not clear if these female members are widows, divorcees or females living in a male-headed household.

Generally, the number of non-active members, those who are not delivering milk to the cooperative, amounts to about 20% of the total number of members. There is a further division of the membership population into payment groups for active members (720 in 2012) and voter groups that are part of the governance structure (about 250 in 2012).

When it comes to female membership, the proportion of women that are participating has been growing slowly. When it comes to financial benefits, the milk processor transfers the agreed payment to the cooperative, through the administration department the registered member is paid in cash or in kind. The ways in which women may share in these benefits is at the discretion of the registered member, de facto, the male head of the household.

Dairy development and gender

In 2009 the FFI dairy development group started to work with KPBS. In this initial phase, an external consultant from the Dutch dairy development consultancy The Friesian assessed the situation. The FFI support to the KPBS cooperative runs through several channels. The FFI team (all male) conducts group trainings that are mostly held at the cooperative. They also visit selected farms that can be considered role models for dairy development. In the following it is important to distinguish between the FFI dairy development advisor and the (evolving) KPBS own dairy extension team.

When FFI starts to employ a professional dairy development advisor to attend to KPBS, the cooperative already has one officer dedicated to dairy extension support. Initially, this KPBS extension officer is replaced by a small experimental own dairy extension team at the cooperative to collaborate on milk quality and quantity improvement.

The KPBS dairy extension team started out as a slightly mixed group with two female dairy extension officers. However, as the FFI dairy development advisor remembers, it did receive a relative high number of female applications. While the experiment seems to work out well, in 2011 this FFI project is accomplished and finishes. The active work on the dairy extension by both the KPBS team and the FFI team is continued with the start of the FDOV project in 2013. The FFI dairy development officer benefits from international funding through the FDOV project, a collaboration, among others, of RFC and Wageningen University and Research.Footnote 6 Within this five year project the KPBS dairy extension team grows and institutionalizes its support with the help of FFI.

In 2018, in a final phase of the FDOV project, the KPBS dairy extension team consists of nine male and three female extension officers. They are available to visit any of the KPBS member households that require support and conduct extension services for small groups (men and women) that come together at the farmer leader’s house or a member household. During a focus group meeting in December 2017, as introductions were made with the question what the background and motivation of the extension officers was to start working for KPBS, a main reason that these dairy extension officers chose to work with KPBS was mentioned again and again: In this agricultural region that is traditionally the ‘golden land’ of the Sundanese community, there is limited choice in being employed. Many of them didn’t want to leave their families or have to travel far every day, so the opportunity to work for KPBS was important to them.

Moreover, the question is what will happen to them once the FDOV project that supports them will end next year.

When the programs end, the feeling is that the spirit will be lower. But the programs have also affected the program of the cooperative, the MCP [Milk Collection Point] and how we develop the farmers. So even when we stop maybe the MCP can be a role model to the coop so they can compete by themselves with other places. And the farmers can continue with the model of other milk collection points (Focus group meeting Pangalengan, 7-12-2017).

The FFI dairy development officer is still active also on distinct projects, but the own KPBS dairy extension team tries to systematically address every member in every payment group (Participant 14, 7-12-2017, Pangalengan).

The FFI dairy development programme has the objective to create a win–win situation by working on better milk quality that benefits FFI, and better income and better livelihoods for smallholder dairy households. As was mentioned in interviews (Interview Participant 2 and 8, 8-12-2016 Bandung), it also aspires to affect the general living standards of women in the cooperative’s member households. A ‘trickle-down’ dynamic of benefits is thus assumed. The FFI dairy development officer’s approach is hands on and aims to build a network in this close-knit organization. As he explains:

The KPBS is run by a family and known as one of the least corrupted cooperatives in West Java…At the start of our work at Pangalengan for the Dairy Development Program, I lived in the hotel here for 6 weeks, to make connections. Every day we visited the farmers and we would help them and give advice. Weekly we would organize focus group meetings for the farmers to exchange experiences and look for improvement. Pangalengan is like my second home (Participant 15, 20-12-2016, Pangalengan).

In many ways, the FFI dairy development activities can also be perceived as investments in the creation of networks and the organization of knowledge platforms. For instance, one of the female role model farmers they are working with (participant 7 in the “Appendix”) has initiated visits to other farms to get introduced to new methods of working that were facilitated by the team. In this way, the FFI work seems to add to the informal enabling factors of women’s empowerment. However, these small contributions still require formalization in practices and policies to be more significant.

KPBS management and gender

When it comes to representation, organizational reports on KPBS show that the Human Resources Management at KPBS is in line with the cooperative’s aims at improving the prosperity of its members and provide jobs for direct stakeholders in the vicinity (Pratama and Hanif 2016). According to its vision and strategy, people working at the KPBS are hired in the ambition to mirror the diversity in Pangalengan’s communities. The ‘identity’ of the KPBS organizations is strongly linked to the regional culture and regional demographics. The KPBS management prefers local people given their knowledge of Sundanese culture, the main ethnicity around Pangalengan, and their affinity in dealing and communicating with the local members. “It does work as a democracy... They also do things like offering free veterinarian services and basic financial training ... the management is quite in touch with the members. They know what is happening on the ground” (Participant 15, 20-12-2016, Pangalengan). This, however, does not necessarily include the diversity related to inclusive business models or women’s empowerment. It seems there has been no policy or drive for women to be equally represented in the board. Nevertheless, in 2012, there was a female board member and female manager of Administration and Finance. Record keeping, planning and control functions are traditionally considered female tasks in Javanese (Indonesian) culture. In the non-automated Milk Collection Points (MCPs) this was put into practice by majority of the registrars being female staff. Twice a day, they took care of the reception of the delivered milk as well as a first test of the milk quality. As this is a part-time function, this ‘job’ seems very suited to female farmers that have to make a combination of their responsibilities as housewives and dairy producers (Interview at MCP, 20-12-2016). As the MCPs are increasingly being automatized under the auspices of the FDOV program, however, these job divisions are changing (Interview Pangalengan, 7-12-2017).

No formal staff development plans are drafted for either men or women. If required, the deal is that Agriterra will provide additional training upon request. No formal training programs focusing on women are advertised, yet, again, if needed, Agriterra can be asked to provide. As one of the female staff explains, she feels constrained in asking for this, however: “They have contact with Agriterra for the leadership program, they don’t do it within the coop.. it would be good to have a training only for women. Agriterra could fill this is in, even if there is no demand from the cooperative. They could offer and then people can react” (Focus group KPBS, 7-12-2017, Pangalengan - translated).

The KPBS voter groups are represented by three elected advisors in the Board of Advisors to the Executive Board (five members). Both Boards are open for elections every 5 years. Annually, a meeting of all members (active and non-active) is organized to vote on major decisions. Remarkably, in several interviews it was mentioned that the majority of those present at these meetings are non-voting women that are part of the voting members’ household. While they do not partake in the discussions or the voting, they are acknowledged as an important dairy producing labour force who understand what is being discussed. They are expected to carry the information back to their family who may be involved in order activities at home.

A gendered approach to KPBS

In summary, at KPBS the informal organization does seem to cater to women quite extensively. Among others, (i) in small and medium sized households, women are acknowledged to take a large responsibility in taking care of livestock; (ii) women are sent to meetings meant to hear the members and aimed at democratic representation; (iii) the KPBS own extension team is mixed and, as interviews show, has been formed with also reaching and training the women who work in dairy in mind; (iv) women are well represented at the Milk Collection Points as administrators and assessors of the quality of the milk before it is transported to the processing plant; (v) the identity of the KPBS organization is strongly intertwined with regional culture and demographics.

It seems, in practice, the formal organization that has ‘voice’ only, does not seem to overlap with the informal organization that runs most activities in dairy development and is empowering some of the women in practice. Moreover, in Sundanese logic, women inherently take care of the cows in smallholder households and take part in farming system decision making.

Dairy households and gender

During a first household visit, the female farmer described her day:

I assist my husband in milking [at 7 am and 4pm]. Then I do the household and take care of the children. Later, sometimes, I go to get the feed when my husband is busy. Fortunately, our sons are older now and they have a motor, so they can help collect the forage. Collecting grass takes up a lot of time… I used to have a shop in the community, but now I am too busy with dairy farming…. Everything I have I owe to dairy farming ... In the future, I would want my children also to be dairy farmers (Participant 6, 20-12-2016, Pangalengan-translated)

Considered a role model in the FFI dairy development program, the family that runs this medium size dairy farm (12 cows) is perceived as ‘succesful’. The husband’s success in dairy farming has led to the housewife being more and more active in dairying. Giving up her own activities in the community and running her shop, she has taken over an equal proportion of the labour needed to produce milk. This is needed as her husband has taken on more responsibilities in the cooperative and the local community and is away from home quite often. Next to their own labour they also hire additional external help, but this is not needed fulltime.

The participants from the first family that was visited state that their main constraint is the lack of space they have to build adequate stables for the cows. The livestock is now spread over two locations in the village, but these are full and more space is required as the livestock herd continues to grow. The second family visit illustrated a very different family situation: “My wife is one of the two elected female board members. She did not stand for election but was recommended by the members. She is the chair and people can come to her with problems. It does not mean she has a lot of real power… She is from a dairy farming family. Even in 1985 she had her first cow when she was very young” (Participant 7, 20-12-2016, Pangalengan-translated).

In the second family we visited, the wife is considered a role model female dairy farmer by the FFI dairy development program. As his wife was out at the market to meet with people and sell some products, we spoke to her husband, who also grows crops. He told us that his agricultural cooperative does not provide him with help to grow better crops so he is very positive about KPBS and its dairy development. The husband described his wife as an exceptional person who shows both leadership as well as technical talent as a dairy farmer within the cooperative. This is seconded by the FFI dairy development officer that accompanied me. He explains: “She is remarkable in the way she registers and administrates everything on the farm. Very meticulous. Very active and taking initiatives. Very curious, seeking information. Both in farming but also within the community” (Participant 15, 20-12-2016, Pangalengan). While he considers the many constraints their dairy farm faces, such as a lack of water supply, no natural resources to forage for feed and a lack of land to build additional stables, the husband sees a future for women in dairying in Pangalengan. In his view, more women can be empowered to become a dairy farmer by: “Breaking with traditions ... there are no examples, we need role models ... they need to see how other people do it ... On dairy development, we already know what could work, we just need more information on how to best do it. The cooperative is getting stronger on this and this gives us a better life” (Participant 7, 20-12-2016, Pangalengan). In this he wants to share his idea that women’s empowerment is largely a question of agency and personal characteristics but can be supported by the local institutional structures and acknowledgement by the dairy development teams.

The all-male externally funded FFI dairy development work is working on better quality and better income for selected smallholder dairy households at the cooperative organization. Additionally, the slightly mixed KPBS own dairy development extension team seems to work towards the same goals with a representation of the whole population of member farmers in mostly face-to-face activities at the household level. Neither team formally addresses issues of women’s empowerment. However, informally they do show awareness of gender-related differences in access that are related to inequality regimes. These unequal relations are relations as much to dimensions of wealth, social class and human capital as to gender per se.

For instance, as an indicator of the relevance of more in-depth research to compare the two teams, is was shown that men are the explicit focus of the formal dairy development activities employed by the FFI officer. This is apparent in, among others:

-

i.

The lack of female extension workers in the technical milk quality training;

-

ii.

The absence of a gender-sensitive approach to extension program design, and;

-

iii.

The access of women to the trainings not being prioritized, enforced or even required.

Discussion

Research has shown that, for dairy development efforts to be effective, the inclusion of the female farmers’ voices is essential (e.g., Bock and Van der Burg 2017; Kabeer 2005; Perrons 2005). If dairy development in cooperatives is to reach its objectives, they should not remain disempowered in these organizations as their positions as producers, their knowledge and insights in milk quality improvement as well as the importance of their representation in decision making will allow for an integrated approach to this part of the dairy value chain.

Presenting evidence from a case study of KPBS Pangalengan in West Java, Indonesia, the exploration in this article is built on the research question what distinct meso- and macro-level institutional dynamics, identified as inequality regimes and complemented by crosscutting dimensions including culture and power, affect dairying women in contributing to dairy development. This research question is answered by exploring inequality regimes evolving from regulative institutions (laws, rules and regulations) and normative institutions (social norms and traditions) that help structure gendered positions with attention to the cross-cutting social constructions that frame gender positions as they are interwoven with, among others, social class and education.

At the national level, and as a contribution to those working in the field, the most prominent inequality regimes that were identified to affect the equality of gender relations are:

-

i.

The ambitions for pro-poor and inclusive development that are voiced in recent governmental strategic plans have not materialized in concrete measures. In politics, thus, the scant rhetoric of gender mainstreaming seems to outstrip efforts to develop projects aimed at equalizing gender relations. Social inequality persists as an important barrier to economic development at all levels of society, including gender relations.

-

ii.

Formally, when it comes to gender, few effective measures seem to support the efficient and effective development of the dairy cooperative. Policy formulation, implementation and enforcement are not well organized. Thus, despite the contributions of input to extension efforts at the level of GKSI, no explicitly gender inclusive formal policies and regulations as imposed on cooperatives.

-

iii.

Informally, social norms projected on gender positions by the Indonesian patriarchal system and the Islamic revival are generally accepted. These can be considered important to maintain mechanisms that sustains a diversity of inequality regimes. Gender disempowering norms have re-institutionalized in recent processes of deepening political and religious austerity.

-

iv.

The crosscutting dimensions of education, property ownership, human capital and social class at work at KPBS seem to diminish the ‘cooperative advantage’ as access to resources is captured by the selected ‘elites’ instead of offering equal access.

-

v.

Culture, mentality, local history and climate are strong predictors of the structure, representation and identity of the cooperative as well as the opportunities open to its members.

At the organizational level, this study shows that gender disempowering inequality regimes seem to be re-enforced by local and international players. While the vacuum in governmental engagement has been filled in part by private companies that have actively taken up dairy development extension in collaboration with cooperatives, this does seem to bring institutional change. However, it also creates new dependencies as the focus group meeting with dairy extension officers brings forward. By creating jobs, hope and a future in an area with few other economic activities, young people commit to the dairy cooperative, time will have to tell if this is an investment that can be sustained on the long term.

In illustration, observations on the FFI dairy development officer and the KBPS dairy extension team active at KPBS Pangalengan provide examples of the way female dairy farmers are affected by dairy development activities. In the limited case study description, the KPBS Pangalengan cooperative serves as an example of a mixed-sex, dairy cooperative on West Java, Indonesia. In a short delineation, the formal and informal practice surrounding membership, the own and FFI practices in dairy development and the access to resources are outlined. The inequality regimes governing the cooperative include practices that, while not explicitly excluding women on an individual level, do result in the (mostly) male head of household to be best represented in the KPBS governance structure.

While there are no policies to exclude women, the FFI dairy development program is not explicitly working on including women in system empowerment within the cooperative (see also the arguments in Nippierd 2002). The dairy development support is selective in that it is not available to all members and payment groups but only to selected exemplary households. While a gender blind approach could have resulted in gender exclusion, as adherence to formal institutions naturally leads to the ‘masculinization’ of cooperative roles, due to the informal networks that are built by the FFI officer involved, this has actually resulted in a bottom-up evolution of a slightly mixed and more representative own dairy extension team at KPBS as argued by Kabeer (2005). Findings suggest that both dairy development teams could play an important role in networking and building a ‘female farmer community’ [a ‘genderscape’ of interconnected networks or relations as proposed by Krishna (2004)] to share knowledge on innovations and best practices thus informally contributing to women’s empowerment in cooperatives (see also Tesfay and Tadele 2013).

While it is impossible to change all institutions impacting on women’s empowerment in Indonesian society, the dairy development activities instigated with donor funded projects at KPBS could function as a start to profound bottom up change in informal gender relations. Considering that change is always happening, the direction and degree of transformation towards women’s empowerment that is occurring requires explicit attention. The informal activities at Pangalengan could be a catalyst to wider transformative dynamics (see, among others, Bock and Van der Burg 2017; International Labour Organization (ILO) 2015; ICA 2015). Overall, however, the membership regulations and human resources management practices at KPBS suggest that the embedded social, political and economic transformative agency that women can accrue within the structure of its regulative and normative institutions on West Java is limited. While formal strategic reports present goals as to include a diversity of members as well as representatives in its governance structure, this does not seem to refer to the explicit inclusion of women in the processes of decision making, access to productive resources, the sharing of benefits or its leadership and representation in practice as is required for true women empowerment to have taken place.

At the grassroots level, the selected families that were visited can be considered exemplary of the ways in which FFI dairy development wants to support the cooperatives to innovate and professionalize. Knowledge management, network building and facilitating grassroots initiatives are an important aspect in their program to build commitment and empowering cooperative members. As mentioned, this is not explicitly aimed at providing extra support to include women but does not exclude them either as is the informal norm. In practice, thus, this kind of support seems to contribute to informal women’s empowerment but leaves room for upgrading formal practices and policies.

While this study aimed to make a contribution to a much too unknown research field, unfortunately, the absence of comprehensive knowledge bases on women’s empowerment in agricultural cooperatives has made systematic comparison and triangulation of findings impossible. The groundbreaking work of White (1984, 2016) on agricultural change in Java, Nippierd (2002) and recently Clugston (2014) and Dohmwirth (2014) on gender in cooperatives are exceptional in this respect. To allow for better analysis and comparison in the future, it is particularly important to create accessible knowledge bases to collect empirical data and best practice examples of efforts to equalize gender relations in different contexts and farm sizes. Lacking these, for the moment, several major findings resulting from this limited exploration may already serve as suggestions for further study.

The findings during these visits illustrate a dynamic that is proposed by separate strands of literature focusing on, among others, migration, rural studies and in the study of natural resource management and gender (See, among others: Blackwood 2008; Robinson and Bessell 2002; Schaner and Das 2016). The practical relevance of the finding that, on the one hand, women have lost part of the informal power and influence that accompanied their position in communities. This is in line with the trend of ‘masculinization’ that can be identified in agrarian areas. Masculinization refers to the increasing formalization and professionalization of organizational processed that have advanced male dominance in procedures and their monopoly on property and resources (Blackwood 2008). This masculinization may be considered a main constraint to the equalization of gender relations in cooperatives. However, on the other hand, informally, an increasing ‘feminization’ at the smallholder farm level can be discerned as female farmers take over when men are away for to, among others, fulfil their formal duties in the cooperative or for labour migration (long-term). Practitioners working on gender relations often underestimate the range of this informal female empowerment. Despite these feminization dynamics, their informal roles do not bring these women the legal, political and social status that it brings to men and this illustrates that women’s empowerment is far from achieved in Indonesian dairy cooperatives (Kelkar 2007; Resurreccion and Elmhirst 2008). In this respect little seems to have changed in the work division and decision making powers in farmer households over the last 40 years, despite technological innovation and development support. It goes to show that even with improved information on rural labour use, however reliable and relevant and however widely disseminated, this does not automatically lead to improved recommendations for action. In practice, the conclusion can still be:

Under these conditions, enhancement of women’s roles should not emphasise skills to increase their income-earning capacity ... Women clearly will be more productive in housework than in work outside the home. Replacement of their role in the home by outsiders or other family members will reduce productivity in this work, which in turn will harm household management. Enhancement of rural women’s roles can be achieved by increasing the efficiency of women’s household work.’ (Sigit [198 1:3]; my translation.) (White 1984, p. 20)

This article has again illustrated the ways in which the cooperative organization is an institutional microcosm of the formal and informal rules that govern society at large, and not a utopian playground that allows for innovative alternative social experiments. However, future longitudinal research is needed to produce ‘thick’ ethnographic descriptions that provide more detailed comparisons of local cooperative and standardized general dairy extension methods and establish if these methods of dairy development lead to distinct local outcomes in the longer term. Also, in future research the nature and thresholds of the relationship between farm size, farming system, availability of labour resources and female dairying activities could be explored in relation to rural trends in farmer household’ ‘masculinization’ and ‘feminization’, as identified above. Understanding the small scale complexity of these institutional dynamics merits our attention all the more when it comes to gender relations. For only if we can identify some basic mechanisms that govern the actions of people in places can we hope to start creating space for larger scale institutional transformation.

Notes

While only marginally touched upon here, intersectionality is considered a relatively new paradigm in gender studies that explicitly addresses also cross-cutting norms and ideologies related to the gender inequalities that may be identified. The intersectional approach, in this article, is considered complementary as well as overlapping with inequality regimes and stresses the interwoven nature of, among others, gender, class and education and how they can mutually strengthen or weaken each other (Winkler and Degele 2011).

LIQUID is the Local and International business collaboration for productivity and QUality Improvement in Dairy chains in Southeast Asia and East Africa. More information on http://liquidprogram.net.

Research has shown that the impact of macro-, meso- and micro-level formal and informal institutional dynamics in the dairy sector is bound by their embeddedness. This means that the influence of culture, cognition and power as well as the outcome of policies and regulations and the diffusion of norms and values will constitute different (and changing) prioritizations in distinct locations, in distinct socio-cultural contexts and within distinct political power dynamics (Van der Lee et al. 2014; Thornton et al. 2012). Given the social construction of these realities, a prioritization of institutions that impact on women’s empowerment has little added value in this article.

This is needed as, both men and women (but not all of them) have stronger cultural influences than others not necessarily because of their gender, but on their ‘symbolic capital’, their cultural significance in the community. This has to do with their families being of a higher social class, or the way their families lead a religious boarding school (Pesantren, in Bahasa) and thus become a knowledge center for others. In addition, the cooperatives need to also be scrutinized in relation to the existing power relations—something that can affect the extent to which gender is addressed.

It merits mentioning here that, of course, and Ben White emphasized on writing about gender relations on Java: “In areas where the majority of cases follow the norm there are always significant exceptions; in other areas even the majority of cases do not follow the norm. This might be held to point to the existence of considerable room for manoeuvre, room for struggle and room for change..”(White 1984, p. 28).

Faciliteit Duurzaam Ondernemen en Voedselzekerheid (FDOV) [Facility Sustainable Business and Food Security] a partnership between RFC, the Wageningen University and Research, Agriterra and the Rijksdienst voor Ondernemend Nederland (RVO) [Netherlands Enterprise Agency].

Abbreviations

- FDOV:

-

Faciliteit Duurzaam ondernemen en Voedselzekerheid (Facility [for] Sustainable Business and Food Security)

- FFI:

-

Friesian Flag Indonesia

- GKSI:

-

Gabungan Koperasi Susu Indonesia (Union of Indonesian Dairy Cooperatives)

- KPBS:

-

Koperasi Peternak Bandung Selatan (Cooperative of South Bandung Dairy farmers)

- KUD:

-

Koperasi Unit Desa (Community-based cooperatives)

- LIQUID program:

-

A NWO-Wotro financed global challenges program, abbreviation for Local and International Business collaboration for productivity and QUality Improvement in Diary chains in Thailand, Indonesia, Kenya and Tanzania

- MCP:

-

Milk collection point

- RFC:

-

Royal Friesland Campina (The Netherlands)

References

Acker, J. 2006. Gender, class and race in organizations. Gender & Society 20: 441–464. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243206289499.

Agarwal, B. 2003. Gender and land rights revisited: exploring new prospects via the state, family and market. Journal of Agrarian Change 3: 184–224. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0366.00054.

ASEAN Foundation. 2008. Empowering women: Building capacity in entrepreneurship and cooperatives. Jakarta: ASEAN.

Asian Development Bank (ADB). 2012. Development effectiveness brief Indonesia: Reforms for resilient growth. Manila: ADB.

Basu, P., and J. Chakraborty. 2008. Land, labor, and rural development: Analyzing participation in India’s village dairy cooperatives. The Professional Geographer 60: 299–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330120801985729.

Batliwala, S. 2007. Taking the power out of empowerment: An experiential account. Development in Practice 17: 557–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520701469559.

Benson, A., and T. Jafry. 2013. The state of agricultural extension. An overview and new caveats for the future. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 19: 381–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2013.808502.

Blackwood, E. 2008. Chapter 1. Not your average housewife. Minangkabau women rice farmers in West Sumatra. In Women and work in Indonesia, eds. M. Ford, and L. Parker, pp. 17–40. London: Routledge.

Bock, B. B., and M. Van der Burg. 2017. Gender and international development. In Gender and rural globalisation: International perspectives on gender and rural development, eds. B. B. Bock, and S. Shortall, Wallingford: CABI.

Clugston, C. 2014. The business case for women’s participation in agricultural cooperatives: A case study of the Mandurira sugarcane cooperative Paraguay. Washington, DC: ACDI/VOCA.

Dohmwirth, C. 2014. The impact of dairy cooperatives on the economic empowerment of rural women in Karnataka. MSc Thesis, Faculty of Life Sciences. Berlin: Humboldt University.

Duguid, F., and N. Weber. 2016. Gender equality and women’s empowerment in co-operatives. Brussels: ICA.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). 2011. The state of food and agriculture 2010–2011. Women in agriculture: Closing the gendergap for development. Rome: FAO.

Ford, Michele, and Lyn Parker. 2008. Women in Indonesia. London: Routledge.

Graham Davies, Sharyn. 2005. Women in politics in Indonesia in the decade Post-Beijing. Oxford: UNESCO.

Harsono, Andreas. 25 November. 2014. Indonesian women’s rights under siege. Human Rights. https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/11/25/indonesian-womens-rights-under-siege. Accessed 19 May 2018.

International Cooperative Alliance (ICA) Asia and Pacific. 2015. Resource guide for advanced training of cooperatives on entrepreneurship development of women and gender equality. Brussels: ICA.

International Labour Organisation (ILO). 2002. Promotion of cooperatives recommendation 2002. http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:R193. Accessed 19 May 2018.

International Labour Organisation (ILO). 2015. Advancing gender equality: The cooperative way. Geneva: ICA & ILO.

International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). 1985. Women in rice farming. Proceedings conference on women in rice farming systems. London: Gower Publishing Company.

Jafry, T., and V. Sulaiman. 2013. Gender-sensitive approaches to extension programme design. Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 19 (5): 469–485.

Janszen, A., and L. Veld. 2012. Company assessment KPBS Pangalengan, 15-17 March 2012, West Java, Indonesia. Arnhem: Agriterra.

Kabeer, N. 1999. Resources, agency, achievements: reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Development and Change 30: 435–464. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00125.

Kabeer, N. 2005. Gender equality and women’s empowerment: A critical analysis of the third millennium development goal. Gender & Development 13: 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552070512331332273.

Kelkar, G. 2007. The feminization of agriculture in Asia: Implications for women’s agency and productivity. Taipei. Taipei: Food and fertilizer technology center (FFTC).

Krishna, S., ed. 2004. Livelihood and gender: Equity in community resource management. New Delhi: SAGE.

Kustiari, R. 2014. Livestock development policy in Indonesia. FFTC Agricultural Policy Articles. http://ap.fftc.agnet.org/ap_db.php?id=294&print=1. Accessed 19 May 2018.

Laven, A., and R. Pyburn. 2015. Facilitating gender inclusive agri-business. Knowledge Management for Development Journal 11 (1): 10–30.

Lecoutere, E. 2017. The impact of agricultural co-operatives on women’s empowerment: Evidence from Uganda. Journal of Cooperative Organization and Management 5: 14–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.com.2017.03.001.

Majurin, E. 2012. How women fare in East African cooperatives: The case of Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. Dar es Salaam: CoopAfrica/ILO.

Najib, L. 1986. Factors relating to female work force participation in three central Javanese communities, Project INS/79/P15. Jakarta: National Institute of Science. Indonesian Institute of Science. United Nations Fund for Population Activities (UNFPA).

Nippierd, A. 2002. Gender issues in cooperatives. Geneva: ILO.

Nippierd, A., and C. Holmgren. 2002. Legal constraints to women’s participation in cooperatives. Geneva: ILO Coopreform Program.

Nugraha, D. S. 2010. Extending the concept of value chain governance: An institutional perspective. Comparative case studies from dairy value chains in Indonesia. PhD Dissertation. Berlin: Humboldt Universitaet.

Palis, F. G. 2006. The role of culture in farmer learning and technology adoption: A case study of farmer field schools among rice farmers in Luzon, Philippines. Agriculture and Human Values 23: 491–500.

Perrons, D. Fall. 2005. Gender mainstreaming and gender equality in the new (market) economy: An analysis of contradictions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pratama, R., and T. Hanif. 2016. Developing the economic potential of agro-tourism. A case of Pangalengan dairy farm. Indonesian Journal of Educational Review 13: 3045–3054.

Resurreccion, B. P., and R. Elmhirst. 2008. Gender and natural resource management. Livelihoods, mobility and interventions. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing.

Robinson, K., and S. Bessell. 2002. Women in Indonesia. Gender, equity and development. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Royal FrieslandCampina. 2017. Dairy development programme. https://www.frieslandcampina.com/en/sustainability/dairy-development-programme/. Accessed 19 May 2018.

Schaner, S., and S. Das. 2016. Female labor force participation in Asia: Indonesia country study. ADB Economics Working Paper Series, 47. Manila: ADB.

Sharma, B. 2013. Contextualising CSR in Asia: Corporate social responsibilities in Asian economies. Singapore: Lien Centre for Social Innovation.

Sulastri, E., and K. L. Maharjan. 2002. Role of dairy cooperatives services on dairy development in Indonesia – A case study of Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta province. Journal of Development Cooperation 9: 17–40. https://doi.org/10.15027/14388.

Tesfay, A., and H. Tadele. 2013. The role of cooperatives in promoting socio-economic empowerment of women: Evidence from multipurpose cooperative societies in South Eastern zone of Tigray, Ethiopia. International Journal of Community Development 1: 1–11. https://doi.org/10.11634/233028791402325.

Thornton, P., W. Ocasio and M. Lounsbury. 2012. The Institutional Logics Perspective. A new approach to culture, structure and process. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

United Nations Development Program. 2016. Gender inequality index. http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/gender-inequality-index-gii. Accessed 19 May 2018.

Valdivia, C. 2001. Gender, livestock assets, resource management, and food security: Lessons from the SR-CRSP. Agriculture and Human Values 18: 27–39.

Van der Lee, J., J. Zijlstra, and S. Van der Vugt. 2014. Milking to potential. Strategic framework for dairy sector development in emerging economies. Discussion paper, CDI and WUR Livestock Research.

White, B. 1984. Measuring time allocation, decision making and agrarian changes affecting rural women: examples from recent research in Indonesia. IDS Bulletin 15 (1): 18–33.

White, B. 2016. Changing childhoods: Javanese village children in three generations. Journal of Agrarian Change 2012: 81–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0366.2011.00338.x.

Win, T. L.. 2014. Time running out for Indonesia’s stalled gender equality bill. Thomson Reuters Foundation News. http://news.trust.org//item/20140407102159-sdf37/. Accessed 19 May 2018.

Winkler, G., and N. Degele. 2011. Intersectionality as multi-level analysis: Dealing with social inequality. European Journal of Women’s Studies 18: 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12039.

Worldbank. 2012. World development report 2012. Gender equality and development. Washington, DC.: Worldbank.

Ybema, S., D. Yanow, H. Wels, and F. Kamsteeg. 2009. Studying everyday organizational life. In Organizational ethnography: studying the complexities of everyday life, eds. S. Ybema, D. Yanow, H. Wels, and F. Kamsteeg, pp. 1–20. London: SAGE.

Zussman, R. 2004. People in places. Qualitative Sociology 27: 351–363. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:QUAS.0000049237.24163.e5.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the support of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research’ Science for Global Development organization (NWO-Wotro) through the Global Challenges Fund for the Local and International business collaboration for productivity and Quality Improvement in Dairy chains in Southeast Asia and East Africa (LIQUID) program (http://liquidprogram.net) in preparing this paper. The feedback Prof. dr. ing. Bettina Bock; the students and sponsors of the Wendy Harcourt masterclass (Wageningen University and Research) and the Intersectionality in Practice workshop at the Migration and Diversity Center (MDC) at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, as well as the practical advice of Agnes Janszen (Agriterra) have been of great value, thank you all for your help.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Anonymized overview participants

Gender | Location interview | Function/organisation | |

|---|---|---|---|

1 | M | Bandung, West Java, Indonesia | Professor Animal Husbandry/DRPMI Universitas Padjadjaran |

2 | M | Bandung, West Java, Indonesia | Dairy Development Manager and FDOV Project Manager/Multinational Milk Processor 1 |

3 | F | Wageningen, NL | Professor Rural Sociology (Gender)/Wageningen University & Research |

4 | M | Wageningen, NL | Expert Southeast Asian Dairy Industry and FDOV project leader at Pangalengan/Wageningen University and Research |

5 | M | Bandung, West Java, Indonesia | Emeritus Professor Rural Sociology (Youth)/Center for Social Analysis |

6 | F | Pangalengang, West Java, Indonesia | Female Dairy Farmer, visit 1/KPBS Pangalengang Member Household, 12 cows and part of the FFI exemplary farmers group |

7 | M | Pangalengang, West Java, Indonesia | Husband of Female Dairy Farmer, visit 2/KPBS Pangalengang Member Household, 10 cows and part of the FFI exemplary farmers group |

8 | M | Bandung, West Java, Indonesia | Fresh Milk Relationship Manager/Multinational Milk Processor 1 |

9 | F | Bennekom, NL | Senior Researcher Law, Governance and Development in Indonesia/Van Vollenhoven Institute, Leiden |

10 | M | Bandung, West Java, Indonesia | Young Farmer, rolemodel for Farmer2Farmer visit/Former Chair of Dutch Agrarian Youth Contact |

11 | M | Bogor, West Java, Indonesia | Expert Cooperative Studies/Bogor Agricultural University |

13 | M | Arnhem, NL | Business Advisor Agri-business/Foundation supporting professional development of Farmers and Cooperatives |

14 | M | Bandung, West Java, Indonesia | Dairy Development Program Jr. Extension Manager, Coordinator Experts in the field/Multinational Milk Processor 1 |

15 | M | Pangalengan, West Java, Indonesia | Dairy Development Field manager/Jr Quality manager (Pangalengang) |

16 | M | Amersfoort, NL | Manager Dairy Development Program Southeast Asia/Multinational Milk Processor 1 |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wijers, G.D.M. Inequality regimes in Indonesian dairy cooperatives: understanding institutional barriers to gender equality. Agric Hum Values 36, 167–181 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-018-09908-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-018-09908-9