Abstract

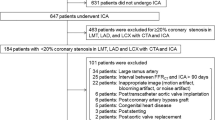

With the aim of assisting interventional cardiologists during decision making for revascularization, reduced-order (0D) approaches have been developed to predict the true fractional flow reserve (FFRTrue) of individual stenoses in multiple-lesion arrangements. In this study, a general equation was derived to predict the FFRTrue of a left main (LM) coronary stenosis with downstream lesions, one in the left anterior descending (LAD) and the other in the left circumflex (LCx) artery, and distinct collateral circulations supplying each daughter artery. An in vitro model mimicking the fractal nature of LM bifurcation trees with collateral branches was developed to validate the FFR values obtained with the prediction model (FFR ModelPred ). Our results demonstrated that: (1) considering collaterals significantly improved the FFR ModelPred estimation for a moderate LM stenosis with two downstream lesions as compared to computations with no collateral consideration (p < 0.001): mean absolute error |FFR ModelPred − FFRTrue| ± SD was equal to 0.02 ± 0.01 vs. 0.04 ± 0.02 respectively, and (2) Deviations from FFRTrue for LM stenoses are correlated to both, downstream lesion severities and collateral developments. The present study supports the hypothesis that collateral circulations supplying the LAD and LCx must be considered when predicting the FFRTrue of an LM stenosis with downstream lesions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- FFRApp :

-

Apparent FFR of the LM lesion

- FFRTrue :

-

True FFR of the LM lesion

- FFRPred :

-

Prediction of the true FFR of the LM lesion

- FFRG1 :

-

Global FFR of the LM + LAD stenoses

- FFRG2 :

-

Global FFR of the LM + LCx stenoses

- CFI1 :

-

Collateral flow index of the LAD branch

- CFI2 :

-

Collateral flow index of the LCx branch

- k :

-

Flow ratio between healthy LAD/LCx branches

References

Daniels, D. V., M. van’t Veer, N. H. J. Pijls, A. Van Der Horst, A. S. Yong, B. De Bruyne, and W. F. De Fearon. The impact of downstream coronary stenoses on fractional flow reserve assessment of intermediate left main disease. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 5:1021–1025, 2012.

De Bruyne, B., N. H. J. Pijls, G. R. Heyndrickx, D. Hodeige, R. L. Kirkeeide, and K. L. Gould. Pressure-derived fractional flow reserve to assess serial epicardial stenoses : theoretical basis and animal validation. Circulation 101:1840–1847, 2000.

Fearon, W. F., A. S. Yong, G. Lenders, G. G. Toth, C. Dao, D. V. Daniels, N. H. J. Pijls, and B. De Bruyne. The impact of downstream coronary stenosis on fractional flow reserve assessment of intermediate left main coronary artery disease: human validation. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 8:398–403, 2015.

Finet, G., Y. Huo, G. Rioufol, J. Ohayon, P. Guerin, and G. S. Kassab. Structure-function relation in the coronary artery tree: from fluid dynamics to arterial bifurcations. EuroIntervention 6:10–15, 2010.

Huo, Y., G. Finet, T. Lefèvre, Y. Louvard, I. Moussa, and G. S. Kassab. Optimal diameter of diseased bifurcation segment: a practical rule for percutaneous coronary intervention. EuroIntervention 7:1310–1316, 2012.

Huo, Y., and G. S. Kassab. A scaling law of vascular volume. Biophys. J. 96:347–353, 2009.

Karabulut, A., and M. Cakmak. Treatment strategies in the left main coronary artery disease associated with acute coronary syndromes. J. Saudi Hear. Assoc. 27:272–276, 2015.

Kelle, S., A. G. Hays, G. A. Hirsch, G. Gerstenblith, J. M. Miller, A. M. Steinberg, M. Schär, J. H. Texter, E. Wellnhofer, R. G. Weiss, and M. Stuber. Coronary artery distensibility assessed by 3.0 Tesla coronary magnetic resonance imaging in subjects with and without coronary artery disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 108:491–497, 2011.

Kweon, J., and Y.-H. Kim. Reply to the letter to the editor by Saito regarding the article “In vivo validation of mathematically derived fractional flow reserve for assessing haemodynamics of coronary tandem lesions”. EuroIntervention 13:2078, 2018.

Kweon, J., Y.-H. Kim, D. H. Yang, J.-G. Lee, J.-H. Roh, G. S. Mintz, S.-W. Lee, and S.-W. Park. In vivo validation of mathematically derived fractional flow reserve for assessing haemodynamics of coronary tandem lesions. EuroIntervention 12:e1375–e1384, 2016.

Melikian, N., T. Cuisset, M. Hamilos, and B. De Bruyne. Fractional flow reserve - The influence of the collateral circulation. Int. J. Cardiol. 132:e109–e110, 2009.

Oviedo, C., A. Maehara, G. S. Mintz, H. Araki, S.-Y. Choi, K. Tsujita, T. Kubo, H. Doi, B. Templin, A. J. Lansky, G. Dangas, M. B. Leon, R. Mehran, S. J. Tahk, G. W. Stone, M. Ochiai, and J. W. Moses. Intravascular ultrasound classification of plaque distribution in left main coronary artery bifurcations where is the plaque really located? Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 3:105–112, 2010.

Peelukhana, S. V., L. H. Back, and R. K. Banerjee. Influence of coronary collateral flow on coronary diagnostic parameters: an in vitro study. J. Biomech. 42:2753–2759, 2009.

Pellinen, T. J., K. S. Virtanen, L. Toivonen, J. Heikkilä, P. Hekali, and M. H. Frick. Coronary collateral circulation. Clin. Cardiol. 14:111–118, 1991.

Perera, D., S. Patel, L. Blows, E. Tomsett, M. Marber, and S. Redwood. Pharmacological vasodilatation in the assessment of pressure-derived collateral flow index. Heart 92:1149–1150, 2006.

Pijls, N. H. J. Assessment of the collateral circulation of the heart. Eur. Heart J. 27:123–124, 2006.

Pijls, N. H. J., B. De Bruyne, G. J. W. Bech, F. Liistro, G. R. Heyndrickx, J. J. R. M. Bonnier, and J. J. Koolen. Coronary pressure measurement to assess the hemodynamic significance of serial stenoses within one coronary-artery: validation in humans. Circulation 102:2371–2377, 2000.

Pijls, N. H. J., J. A. M. van Son, R. L. Kirkeeide, B. De Bruyne, and K. L. Gould. Experimental basis of determining maximum coronary, myocardial, and collateral blood flow by pressure measurements for assessing functional stenosis severity before and after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Circulation 87:1354–1367, 1993.

Pohl, T., C. Seiler, M. Billinger, E. Herren, K. Wustmann, H. Mehta, S. Windecker, F. R. Eberli, and B. Meier. Frequency distribution of collateral flow and factors influencing collateral channel development. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 38:1872–1878, 2001.

Seiler, C., M. Stoller, B. Pitt, and P. Meier. The human coronary collateral circulation: development and clinical importance. Eur. Heart J. 34:2674–2682, 2013.

Tan, X. W., Q. Zheng, L. Shi, F. Gao, J. C. Allen, A. Coenen, S. Baumann, U. J. Schoepf, G. S. Kassab, S. T. Lim, A. S. L. Wong, J. W. C. Tan, K. K. Yeo, C. T. Chin, K. W. Ho, S. Y. Tan, T. S. J. Chua, E. S. Y. Chan, R. S. Tan, and L. Zhong. Combined diagnostic performance of coronary computed tomography angiography and computed tomography derived fractional flow reserve for the evaluation of myocardial ischemia: a meta-analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 236:100–106, 2017.

Tonino, P. A. L., W. F. Fearon, B. De Bruyne, K. G. Oldroyd, M. A. Leesar, P. N. Ver Lee, P. A. MacCarthy, M. van’t Veer, and N. H. J. Pijls. Angiographic versus functional severity of coronary artery stenoses in the FAME study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 55:2816–2821, 2010.

Tsai, T.-H., and C.-I. Cheng. Stenting or bypass surgery for unprotected left main coronary artery disease-still a long rally to go. J. Thorac. Dis. 8:2292–2295, 2016.

Watanabe, H., N. Saito, H. Matsuo, Y. Kawase, S. Watanabe, B. Bao, E. Yamamoto, H. Higami, K. Nakatsuma, and T. Kimura. In vitro assessment of physiological impact of recipient artery intervention on the contralateral donor artery. Cardiovasc. Revasc. Med. 16:90–100, 2015.

Werner, G. S., B. M. Richartz, O. Gastmann, M. Ferrari, and H. R. Figulla. Immediate changes of collateral function after successful recanalization of chronic total coronary occlusions. Circulation 102(24):2959–2965, 2000.

Yaeger, I. A. A multi-artery Fractional Flow Reserve (FFR) approach for handling coronary stenosis-stenosis interaction in the multi-vessel disease (MVD) arena. Int. J. Cardiol. 203:807–815, 2016.

Yamamoto, E., N. Saito, H. Matsuo, Y. Kawase, S. Watanabe, B. Bao, H. Watanabe, H. Higami, K. Nakatsuma, and T. Kimura. Prediction of the true fractional flow reserve of left main coronary artery stenosis with concomitant downstream stenoses: in vitro and in vivo experiments. EuroIntervention 11:e1249–e1256, 2016.

Yong, A. S. C., D. Daniels, B. De Bruyne, H.-S. Kim, F. Ikeno, J. Lyons, N. H. J. Pijls, and W. F. Fearon. Fractional flow reserve assessment of left main stenosis in the presence of downstream coronary stenoses. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 6:161–165, 2013.

Yong, A. S. C., A. Javadzadegan, W. F. Fearon, A. Moshfegh, J. K. Lau, S. Nicholls, M. K. C. Ng, and L. Kritharides. The relationship between coronary artery distensibility and fractional flow reserve. PLoS ONE 12:1–16, 2017.

Zhang, J. M., et al. Advanced analyses of computed tomography coronary angiography can help discriminate ischemic lesions. Int. J. Cardiol. 267:208–214, 2018.

Zhang, J. M., L. Zhong, T. Luo, A. M. Lomarda, Y. Huo, J. Yap, S. T. Lim, R. S. Tan, A. S. L. Wong, J. W. C. Tan, K. K. Yeo, J. M. Fam, F. Y. J. Keng, M. Wan, B. Su, X. Zhao, J. C. Allen, G. S. Kassab, T. S. J. Chua, and S. Y. Tan. Simplified models of non-invasive fractional flow reserve based on CT images. PLoS ONE 11:1–20, 2016.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank to Dr. Yves Usson for his advice regarding the experiment. This research was supported by grants from Labex CAMI-France (project SIMPLE) and the Mexican National Council for Science and Technology (CONACYT).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Associate Editor Ender A. Finol oversaw the review of this article.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Derivation of the General True FFR Prediction Equation for an LM Stenosis with Two Downstream Lesions and Two Collateral Circulations Supplying the LAD and LCx

Background

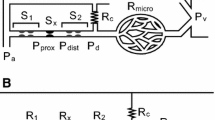

Pijls et al.18 described the flow in a single stenosed coronary artery supplied by a collateral circulation. They found and validated the two following relationships:

where (\( P_{\rm d} ,P_{\rm d}^{{\prime }} \)), (\( P_{\rm W} ,P_{\rm W}^{{\prime }} \)) and (\( Q_{\rm S} ,Q_{\rm S}^{{\prime }} \)) are the distal pressures, wedge pressures and hyperemic coronary flows going through the stenosis before and after revascularization, respectively. Q NS is the normal coronary artery flow. Superscript ‘N’ will be used for normal state (State N) or healthy configuration (i.e., without stenoses).

Proposed Model

After removing the two downstream lesions R1S and R2S (State A′, Fig. 1b), the distal pressures of the treated lesions are both equal to the distal pressure of the LM stenosis (i.e., \( P_{\rm 1d}^{{\prime }} = P_{\rm 2d}^{{\prime }} = P_{\rm m}^{{\prime }} \)). Moreover, the coronary occlusion pressures \( P_{{1{\text{W}}}}^{{\prime }} \;{\text{and}}\;P_{{2{\text{W}}}}^{{\prime }} \) are assumed to be different for each coronary branch (Fig. 1b). By considering the previous relationships (Eqs. (A.1) and (A.2)) for LAD and LCx coronary arteries supplied by their own collateral circulation (Fig. 1), one can write:

with

By substituting Eq. (A.4a) into Eq. (A.3a) and Eq. (A.4b) into Eq. (A.3b) one can obtain:

Since the LM stenosis resistance Rm does not vary from State A (Fig. 1a) to State A′ (Fig. 1b) and because it was assumed that the flow through a resistance satisfies Poiseuille’s law (i.e., Resistance = Pressure gradient/Flow), one can derive the following relationship:

Substituting Eqs. (A.4a,b) and (A.5a,b) into Eq. (A.6b) yields to:

In this model the collateral flow index (CFI), which describes how developed is the collateral circulation, is calculated as \( {\text{CFI}}_{1} = P_{{1{\text{W}}}} /P_{\text{a}} = P_{{1{\text{W}}}}^{{\prime }} /P_{\text{a}}^{{\prime }} \) for the myocardial resistance supplied by the LAD (R1) and as \( {\text{CFI}}_{2} = P_{{2{\text{W}}}} /P_{\text{a}} = P_{{2{\text{W}}}}^{{\prime }} /P_{\text{a}}^{{\prime }} \) for the myocardial resistance supplied by the LCx (R2). Notice that CFI1 and CFI2 do not vary from State A to State A′.18

Dividing the numerators and denominators on both sides of Eq. (A.7) by Pa and \( P_{\rm a}^{{\prime }} \) respectively, allows us to obtain the following relationship:

where FFRApp = Pm/Pa, \( {\text{FFR}}_{\text{Pred}} = P_{\rm m}^{{\prime }} /P_{\text{a}}^{{\prime }},\) FFRG1 = P1d/Pa and FFRG2 = P2d/Pa (see “Materials and Methods” section for FFR definitions).

Then, dividing by Pa the numerator and denominator of the right side term of Eq. (A.8), gives:

To isolate FFRPred, Eq. (A.9) transforms as follow:

Finally, dividing the numerator and denominator of the right side term of Eq. (A.10) by \( Q_{\rm 2S}^{\rm N} \) and defining “k” as the flow ratio \( Q_{\rm 1S}^{\rm N} /Q_{\rm 2S}^{\rm N},\) allow us to obtain the original predictive equation for the true hemodynamic significance of the LM lesion (i.e., Eq. (1)).

The parameter “k” represents the flow ratio between LAD and LCx branches for a non-pathological LM bifurcation (i.e., at healthy configuration without collaterals). This is when no stenotic lesions (Rm, R1S and R2S) are present (i.e., when FFRG1 = FFRG2 = FFRApp = 1) and when both collateral circulations supplying the LAD and LCx are poorly developed (i.e., when CFI1 = CFI2 ≈ 0).

Flow-Diameter Scaling Law for “k” Calculation

From Kassab’s group work6 it is know that flows and diameters in a vascular tree follow the next relationship:

where Qstem and Dstem are the flow and diameter of the “stem” or branch of interest (LAD or LCx for this example). Qmax and Dmax are the flow and diameter of the most proximal stem (LM in this case).

The following expressions are obtained for healthy LAD and LCx flows:

Finally,

Experimental Estimation of “k” for the In Vitro Validation

In this model each coronary branch plus its collateral is considered as an individual path to bring blood to a specific myocardial resistance. The total myocardial flow for R1 and R2 can be expressed as follows: Q1 = Q1S + Q1C and Q2 = Q2S + Q2C (see Fig. 1c).

In “healthy configuration” collateral circulations \( Q_{\rm 1C}^{\rm N} \) and \( Q_{\rm 2C}^{\rm N} \) are considered negligible and normal coronary flows \( Q_{\rm 1S}^{\rm N} \) and \( Q_{\rm 2S}^{\rm N} \) are equal to normal myocardial flows \( Q_{1}^{\rm N} \) and \( Q_{2}^{\rm N},\) respectively.18 So, at normal state it is assumed that \( Q_{\rm 1S}^{\rm N} /Q_{\rm 2S}^{\rm N} = Q_{1}^{\rm N} /Q_{2}^{\rm N}.\)

Moreover, at State A′ (Fig. 1d), the flow ratio \( Q_{1}^{{\prime }} /Q_{2}^{{\prime }} \) is equal to the ratio of the myocardial resistances R2/R1 because \( Q_{1 }^{{\prime }} = \left( {P_{\rm m}^{{\prime }} - P_{\rm v}^{{\prime }} } \right)/R_{1} \) and \( Q_{2 }^{{\prime }} = \left( {P_{\rm m}^{{\prime }} - P_{\rm v}^{{\prime }} } \right)/R_{2}.\) Similarly, at “normal state” (i.e., State N) Poiseuille’s law allows us also to write: \( Q_{1 }^{\rm N} = \left( {P_{\rm a}^{\rm N} - P_{\rm v}^{\rm N} } \right)/R_{1} \) and \( Q_{2 }^{\rm N} = \left( {P_{\rm a}^{\rm N} - P_{\rm v}^{\rm N} } \right)/R_{2} \) making the flow ratio \( Q_{1}^{\rm N} /Q_{2}^{\rm N} \) equal to R2/R1 as well. In the end, if the myocardial resistances remain unchanged for a patient, one has:

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Coppel, R., Lagache, M., Finet, G. et al. Influence of Collaterals on True FFR Prediction for a Left Main Stenosis with Concomitant Lesions: An In Vitro Study. Ann Biomed Eng 47, 1409–1421 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-019-02235-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-019-02235-y