Abstract

We explore how crime victimization affects two of the main dimensions of social capital: trust and participation in social groups. Using a large database that includes many Latin American countries, we find that victimization lowers trust, especially in other people and the police. However, participation in social groups is increased as a result of this event. These findings suggest that the net effect of victimization on social capital is miscalculated unless all of its dimensions are taken into account.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Social capital is one of the engines of economic growth (Keefer and Knack 1997; Knack and Zak 2001; Algan and Cahuc 2010). It solves many problems of collective action, reduces the need for formal agreements and improves property rights. Social capital is associated with many positive outcomes that foster prosperity, such as financial knowledge (Guiso et al. 2004). It is also linked with negative outcomes, such as crime. The existing literature generally concentrates on the effect of social capital on crime. Rosenfeld et al. (2001) and Buonanno et al. (2009) showed that social capital can be a strong deterrent to crime. However, the other side of the equation, i.e., the way in which crime affects social capital, has received little attention. Few works have focused on how individual crime victimization affects trust. Corbacho et al. (2015) analyzed the effect of victimization on horizontal and vertical social capital, finding that victims of crime are 10% less likely to trust the police compared to non-victims. Blanco (2013) and Blanco and Ruiz (2013) studied the role of victimization and the fear of crime on trust and support in democracy, along with other dimensions of trust, for Colombia and Mexico, finding a strong negative effect of victimization. In the present paper, we explore whether victimization affects trust in other people and in various types of organizations. In this way we can evaluate whether there are differences between organizations that directly manage law and order, such as the police, and those that do not, such as the media. We consider individual data taken from the AmericasBarometer for all the available Latin American countries from 2004 until 2012. As a result, we have above 100,000 observations, many more than previous studies. Using propensity score matching, we find strong evidence that those who are victims of crime have lower levels of trust. For example, a victim has 7% less trust in other people. We also find that trust is lower in institutions that directly manage law and order, such as the police.

Trust is one of the main features of social capital (Coleman 1994; Putnam 1995, 2000), but not the only one. Other dimensions, such as civic engagement and election turnout, are also important in promoting economic development and reducing transaction costs. Despite their significance, few papers have evaluated the effect of crime on these other dimensions. In particular, we know little about how victimization affects participation in social groups. As far as our knowledge extends, only Bateson (2012) studied its role in political participation, finding a positive effect. In the present paper, we make several contributions: we consider the effect on a variety of social groups, not just political ones. We use the same dataset and econometric technique as those used in the analysis of trust. As the main outcome variable, we use All Groups, a dummy equal to one if the respondent participates once a week in various groups, and zero otherwise. Our econometric analysis shows that victims of any type of crime are about 2.5% more likely than non-victims to participate in some kind of social organization (using a single nearest neighbor). We explain such results using a psychological theory, known as the stress-buffer hypothesis (Cohen and Wills 1985). This states that a victim of crime seeks social support to alleviate the stress caused by such a negative experience. As a consequence, this individual will participate more in such groups. Since we are not psychologists, we will not explore this idea in detail, and do not pretend it to be the only explanation.

As a robustness test, we repeat the estimations with the Chilean victimization survey (Chilean Ministry of The Interor and Public Security 2016), which largely confirms the previous findings. Victims of crime reduce their trust in other people and institutions but increase their participation in social organizations. As a final exercise, we perform the Rosenbaum Bounds (Rosenbaum 2002; Becker and Caliendo 2007) test for the presence of unobservables. This reveals that the results relative to trust are very robust, whereas we should be more cautious about the ones relative to participation.

The findings of this paper are important from a policy perspective. On the one hand, victimization reduces individuals’ levels of social capital via reduced trust. On the other hand, it increases it, via participation in social organizations. This means that it is incorrect to say that victimization reduces social capital. Rather, victimization decreases trust. The net effect of victimization on social capital should be reconsidered in the light of these results.Footnote 1

This paper is organized as follows. In the second section, we review the literature on the links between victimization and social capital. Sections 3 and 4 explain the data, the econometric technique, and present the main results. Section 5 contains the robustness exercises. In the sixth section we conduct several sensitivity tests. Section 7 concludes.

2 Literature review and theoretical background

The majority of the literature has established a crime reducing effect of social capital. In a cross-country study of violent crime, this was shown by Lederman et al. (2002), for the USA by Rosenfeld et al. (2001), and by Buonanno et al. (2009) for Italy. Social capital increases social controls and the social stigma for potential offenders. Only in some particular circumstances might some types of social capital lead to an increase in crime. This is the case of “perverse social capital” in Colombian cartels (Rubio 1997) or “bonding ties” in evangelical Protestant communities in the USA (Beyerlein and Hipp 2005)Footnote 2.

Far fewer studies have analyzed whether and how crime affects social capital. The scarce literature has focused mainly on the effect of victimization on various types of trust. For example, Corbacho et al. (2015) investigated the effect of victimization on vertical and horizontal measures of trust, using Gallup data for 2007. As their crime variable, the authors considered whether 1) a person has been mugged and 2) a person, or his family, had something stolen from them in the previous twelve months. The authors analyzed the effect of being victimized on horizontal trust (in others, friends and business partners) and vertical one (in the police and the judicial system). Non-victims of crime have a 10% higher probability than victims of trusting the police. The results for the other variables are somewhat mixed, with many not statistically significant coefficients. Blanco (2013) and Blanco and Ruiz (2013) are two other important contributions on this topic. The former explored whether victimization and the fear of insecurity lower the support and satisfaction in democracy, trust in various institutions, trust in the criminal justice system, and trust in others. The data for Colombia were taken from the AmericasBarometer (Latin American Public Opinion Project, LAPOP) for the period 2004-2010. Using an ordered logit technique, the author found that victimization lowers satisfaction in democracy and trust in almost all institutions. The author found no effect on trust in other people. In a similar work, Blanco and Ruiz (2013) analyzed whether victimization and a feeling of insecurity affect support for democracy and trust in various institutions. In this case the country under analysis was Mexico, with data taken from the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) and the national victimization survey. The findings are similar to those of Blanco (2013): victimization reduces both support for democracy and various measures of trust in institutions. Along with these studies, many others have shown an indirect relation between victimization and various measures of trust and support for democracy (Carreras 2013; Fernandez and Kuenzi 2010).Footnote 3

We contribute to the existing literature by studying how victimization affects trust in others and institutions. The other studies just mentioned were limited to one or a few countries, but we will consider LAPOP data for all the Latin American countries, for 2004–2012. This means more than 100,000 observations, many more than the existing research on this topic. In addition, we consider many crime categories, a novelty in this literature. Using propensity score matching, we find that victimization negatively affects all types of trust, both vertical and horizontal. Being a victim of crime has the greatest negative effect on trust in other people and the police. We found little effect on trust in institutions not directly related to the management of law and order.

Trust is a major components of social capital, but not the only one. Coleman (1994, p. 302) argued that:

“social capital is defined by its function. It is not a single entity, but a variety of different entities having two characteristics in common: they all consist of some aspect of social structure, and they facilitate certain actions of individuals who are within the structure”.Footnote 4

These components of social capital are also important in promoting economic development. Despite such a multi-dimensional concept, the relation between victimization and other features of social capital has been largely ignored.Footnote 5 We evaluate how and to what extent victimization affects another important dimension of social capital: participation in social groups. Does victimization reduce this dimension of social capital, as it does to trust? Are participation in social groups and trust complements or substitutes? There are many reasons to presume that victimization increases this type of participation, having the opposite effect on trust. First of all, trust is a subjective measure. It is usually measured as the level of confidence in a person/group/institution using a hypothetical scale. On the other hand, participation in social organizations is a more objective measure, as it records the actual participation.Footnote 6 Moreover, when a person is a victim of crime, she is going through a stressful moment which can have harmful psychological and physical effects. These are even more acute if the person does not cope well with the elaboration of such negative event. Psychologists recognize that a useful way to alleviate and ameliorate the negative effects of this experience is through social support. This is the so-called stress-buffer hypothesis (Cassel 1976; Cobb 1976; Cohen and Wills 1985), in that social support buffers (protects) individuals from the negative consequences of stressful periods. Social interaction is beneficial to an individual’s health because it relativizes the importance of the event, provides distraction, and reduces anxiety. Large social networks provide people with regular positive experiences. Therefore, we expect that the effect of victimization on participation would not be negative, i.e., decreasing the stock of social capital, but rather, zero or positive.

As far as our knowledge extends, in the literature there is only one other paper which analyzes a similar relation: Bateson (2012) studied the effect of victimization on political participation using data from various opinion polls. The results show a positive and significant effect of victimization on all types of political participation, with all coefficients below 0.05.Footnote 7 Our work differs and complements it in many ways. First of all, we consider all types of associational networks, and not only political ones. This is consistent with the use of the stress-buffer hypothesis, which affirms that (any) social groups alleviate stress from victimization. In our theoretical framework, a political group is just one type of social group, but not the defining one. Finally, we take into consideration the possible issues of contemporaneity between the victimization and participation variables.

3 Data and econometric strategy

As our preferred estimation technique we will use propensity score matching (PSM) (Rosenbaum and Rubin 1983). We decided to use this technique rather than regression because we are confident that the uncofoundedness condition holds for our data. We employ data from the AmericasBarometer for all Latin American and Caribbean countries for the five included between 2004 until 2012.Footnote 8 Our main treatment variable is the victimization question: “have you been the victim of any type of crime in the last 12 months?” Table 1 shows that the percentage of victimized people ( those who answered yes) over this period is 17.4%, about 146,000 individual observations. Turning to the outcome variables, people were asked their level of confidence in other people and in various institutions. They had to choose from a scale that runs from 1 (no confidence) to 7 (lots of confidence). We created a dummy variable equal to 1 for the values 5, 6 and 7 and labeled trust in other people as Other People. Continuing, we considered trust in the following institutions: the police, the supreme court, the fiscalia, the army, the Catholic Church, the media, labor unions, and political parties. We chose such variables to see whether there is a heterogeneous effect of victimization on trust in “law enforcement related” institutions (the police, the supreme court, the fiscalia) compared to the others. Table 1 shows that political parties are the least trusted (42%), whereas Media is considered the most trustworthy (49.4%).

The choice of the participation variables is quite challenging from an econometric point of view. In order for the PSM method to be valid, the outcome variable cannot anticipate the treatment one. Otherwise, this would imply that the victimization experience is consequent on the decision to participate in social organizations. If we consider a standard participation question that refers to the previous twelve months, we cannot be completely sure that this is valid. After all, a person who participates in social organizations is more likely to go out of the house and, as a result, has a higher probability of being victimized.Footnote 9 The estimated Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATT) might thus be positively biased. Fortunately, in the AmericasBarometers database the respondents were asked not only whether they participated in a given social organization, but also the frequency. Individuals were questioned whether they attended a meeting of such an organization (a) once a week, (b) once or twice a month, (c) once or twice a year, or (d) never. We created a dummy variable equal to one if the person answered once a week and 0 otherwise. Such classification helps us to be quite confident that the treatment (Victimization) precedes the outcome variable. Let us suppose that a person was interviewed on the first of February 2012 and that she was victimized on the first of April 2011. Supposing that the person used to attend a group’s meeting once a week at the time of victimization, she would have had enough time to change behavior and move out of category a), attending once a week. Nevertheless, she might decide not to go to church any more, but since she was attending once a week, she might answer c) rather than d). In any case, she would have 0 in the dummy for participation. The only situation where the respondent would fall in category a) as a consequence of their behavior before being victimized would be if the crime took place in the week right before the interview and the respondent belonged to category a). In such a case, the individual might decide to answer a) even though having changed attendance to less than once a week. Assuming that victimization happens quite regularly over the year, the last event is quite unlikely and would not affect the results.Footnote 10

The participation variables which are available throughout the entire period of 2004 to 2012 refer to religious, community, professional, and political party organizations. We created a dummy equal to one if the respondents declared participating once a week in at least one of these four organizations. We labeled this newly created variable All Groups. A concern with this measure is that victimized people might be more likely to go to self-help organizations. If such participation is made at the expense of other organizations, the rise in participation might not be necessary related to a rise in social capital. In order to take this concern into account, we also employ the variable All Groups-No Prof Org, which considers only participation in religious, community, and political party organizations. We also checked the separate effect of victimization on unions and cooperatives, although there is not data for all five waves. Table 1 shows that \(34.7\%\) of the respondents participated once a week in at least one social organization. Religious organizations make up a large proportion of this percentage.

In the absence of a reliable instrument for the explanatory variable, PSM is the best alternative to regression analysis. The treatment variable, whether the individual has been victimized, could be considered as randomly assigned after controlling for our set of controls. As is common practice with PSM, we consider a rich set of variables that affect simultaneously the treatment, Victimization, and the outcome variables.Footnote 11 Buonanno (2003) offered a good, although not up to date, survey of the socio-economics determinants of crime. For social capital, we have somewhat less literature to base our analysis on. Indeed, the paper by Glaeser et al. (2002) is a prominent study. For Chile, Valdivieso and Villena (2014) provided an interesting analysis of the formation of social capital.

The selection of variables was made following the statistical significance approach. This consists in starting with a parsimonious model and then adding variables, selecting those which are statistically significant. Another requisite is that the control variables should not change as a response or anticipation of the treatment, a condition largely confirmed in our case. We have included age, gender, marital status, years of education, number of children, urban, whether she has low income, Catholic, and life satisfaction on a scale of 1 to 4.Footnote 12 We calculated the probability of being a victim of crime in Table 2 and estimated the model with probit. The coefficients represent the marginal effects. In all the estimations, we included year and country fixed effects.

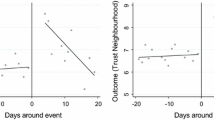

The results show a negative relation with Age, Married, Urban, Low Income, Catholic Church, and Life Satisfaction. On the other hand, being male, educated, and with children, increase the probability of being victimized. These results are in line with the existing literature (Buonanno 2003). Well-off people are more likely to be targeted, as they have more to steal from. This is particularly true since the majority of crime are property crimes. The only coefficient that goes against the literature is Urban, which is negative. Different algorithms for the propensity score analysis yield homogeneous results. The large common support area (Fig. 1) allows us to have good matches for each treated unit and increase the precision of the estimates. Moreover, the probability density functions (pdf) of the propensity score for victimized and non-victimized are very similar.

This means that after conditioning on the control variables, Victimization seems quite randomly assigned. As usual, we need to consider the trade-off between bias and variance of the treatment effect. Having few matches for the treated leads to lower bias but higher variance. We decided to consider three different specifications: a single nearest-neighbor match with replacement (Nearest Neighbor (1)); the 100 nearest neighbor matches with replacement; a radius within 0.03 of the propensity score (Table 3).

We then evaluated the quality of matching for our preferred algorithm, Nearest Neighbor (1), but the results for the other algorithms are similar.Footnote 13 The matching exercise works well in balancing the covariates between treated and untreated. In all cases, we cannot reject the null hypothesis. Table 4 reveals how the matching procedures greatly reduce the mean and variance of the bias. Table 5 shows that, after matching, the R-squared is 0, which means that the explanatory variables do not have any predictive power at all for the probability of being victimized after matching.Footnote 14

4 Results

4.1 Trust

Table 6 reports the ATT for different algorithms for the trust variables. Victims of crime have lower trust in all institutions except Union. The coefficients are highly significant. The negative effect of crime is particularly strong for trust in other people and in institutions that are directly related to the management of law and order. A victim of any type of crime is about \(7\%\) less likely to have a high level of trust in other people, which is the most negative ATT of all. It is closely followed by the Police coefficient, which is 0.065 with the one nearest neighbor algorithm. Supreme Court and Fiscalia follow closely. The lowest coefficient, in absolute terms, is the one for Media, using the 100 nearest neighbor specification.

Compared with the existing literature, our results show some similarities, but also, differences. For example, Corbacho et al. (2015) found a reduction of trust in police by 10%, not too different from our value, 6.5 %. The same authors found a reduction in trust in the judicial system of around 3%, whereas us between 3 and 4 % (trust on the supreme court and the fiscalia). However, Corbacho et al. (2015) did not find a significant on religious organizations whereas we do so.Footnote 15 Continuing, we cannot directly compare our results with Blanco (2013), because it is reported the coefficients employing an ordered logit approach. A main difference is that this author dis not find trust in other people to be affected as we did. Nevertheless, similarly to our study, these authors found a greater negative effect for institutions directly related with the management of law enforcement.

4.2 Participation in social groups

Psychological theory, or simply common sense, leads us to doubt that victimization has the same “negative” effect on participation in social groups as on trust. Table 7 reports the ATTs with participation in various groups as outcome variables. The coefficients are positive and significant for almost all the specifications. A victimized person is likely to participate more in All Groups by about 2.5% compared to a non-victimized person, using the one nearest neighbor specification. This coefficient is lower than the one found for trust in Other People, but still significant. As expected, the result for All Groups-No Prof Org is similar but with a slightly lower coefficient. Continuing, participation in religious organizations and community organizations exhibit the greatest coefficient of those among the organizations that compose All Groups.Footnote 16 On the other hand, Political Party has the lowest coefficient.

We also checked, although not reported, how the coefficients change using a less restrictive time definition. Considering one month and 1 year window, rather than one week, we still have positive and highly significant results. As expected, the coefficients are higher the greater the time window.

These results seem to confirm the stress buffer hypothesis (Cohen and Wills 1985), which affirms that people who are experiencing periods of stress (caused by victimization in this case) seek social support to alleviate the negative consequences of such experiences.

We then considered the effect of different types of crime on All Groups. We decided to prioritize those crime categories that were available for the largest number of waves. Except for the 2008 wave,Footnote 17 we have data from the other four waves for theft, damage, burglary, assault, rape, and kidnapping. The first three are grouped in the the category Property Crime whereas the last three in Violent Crime. As we can see in Table 1, a large majority of the crimes are property crimes: \(13.9\%\) versus less than 1% for violent crime. The results of the propensity score matching can be found in Table 8. In each estimation we excluded all the people that had been victimized by other types of crime from the sample, to avoid contamination effects.Footnote 18 In such a way, our results will not be affected by the behavior of other victims of crime.Footnote 19

Table 8 shows that the effect is positive for all types of crime, although not significant at the conventional level for all specifications. Those who have been a victim of property crime, by far the largest category, increase their participation in All Groups by 1.6%-1.8%, depending on the algorithm employed. We do not find any significant effect for violent crime. The highest coefficient is for Burglary, followed by Assault.

5 Robustness checks

In the previous sections, we made clear that we chose LAPOP data because it allowed us to take into consideration simultaneity issues between the treatment and outcome variables. In this section, we repeat the previous exercises using the Chilean victimization survey. The survey is run by the Chilean Ministry of The Interor and Public Security (2016). It started in 2003, was repeated in 2005, and since then has become annual.Footnote 20 For the purposes of this study, we will use only the 2003 and 2005 waves, which gives us two repeated cross sections.Footnote 21 The reason for doing so is that only in those two waves were there questions on participation in social groups.

The survey’s respondents were questioned whether they, or anybody else in their household, had been victimized in the previous twelve months. This is our “treatment” variable, which we labeled Victimization. In 2003, around 43% of the Chilean population had been victimized, whereas in 2005, the percentage was 38.3%. Around 60% of the victimized individuals had been a victim only once. Among the most frequent crimes, there are property crimes, such as auto theft, general theft, and various types of robberies. Regarding the control variables, we tried to follow as closely as possible the previous specification, depending on the availability of the data. Therefore, we included age, gender, marital status, household size, whether she had obtained a university degree, and whether she had moved within the last four years in the current neighborhood.

Summary statistics are reported in Table 9. As we can see, the level of victimization is much higher than in the LAPOP data: 38.3%–43% vs. 17.4%. Indeed, the fact that the question is at the household level explains part of this difference, but not completely. Again, property crime rates are much higher than violent crime rates.Footnote 22

We first evaluate the effect of being victimized on the level of trust in various institutions. Respondents to the Chilean victimization survey were asked to say whether they had none, some, or a lot of confidence in some of the most important institutions of the country. Here we consider carabineros, the PDI, the Supreme Court, the Ministry of the Interior, judges, deputies, the President of the Republic, and senators.Footnote 23 We created a dummy equal to one if they answered a lot, and zero otherwise. The results of the PSM exercise are displayed in Table 10

Similarly to the previous results, victimized people have lower levels of trust in institutions compared to non-victims. Such decrease is stronger for institutions that are directly in charge of law enforcement. For example, a victim of crime is 4.3% less likely to trust the police. This value is slightly lower than the one found earlier, 6.5%, and the one by Corbacho et al. (2015), 10 %. Continuing, the effect on Ministry of the Interior is sizable and significant. Contrary to our previous exercise and the existing literature (Blanco 2013), we do not find a statistically significant effect for Supreme Court. Victimization is also having little, or no effect, on trust in deputies and senators. For example, the (negative) coefficient for the President of the Republic is only 1.2%.

Continuing, we consider the effect of Victimization on participation in various social groups. People were asked whether they had participated in various social organizations in the previous twelve months. Respondents could choose from among fourteen organizations, ranging from laboral to cultural ones.Footnote 24 We created a dummy, which we called All Groups-INE,Footnote 25 equal to one if the respondent participated in at least one organization. Table 11 shows that those who have been victimized are more likely to participate in social groups than are those who have not been. For example, a victim is 6.1% more likely to participate in any of the above mentioned groups. This coefficient is about 2.5 times higher than the one found in Table 7 with data from LAPOP. Such overestimation could be due to the different timing of the questions (previous twelve months) and the largest number of social organizations in the Chilean victimization survey. Nevertheless, the direction and significance of the coefficients confirms that, if anything, victimized people increase the amount of social capital along this dimension (Table 12).

The coefficents for the other organizations are all positive and significant. The highest ones are for Cultural, Voluntary, and Sports. The social group with the lowest coefficient is Political. Probably, people prefer to alleviate their stress by participating in organizations which are more “recreational”. Again, the choice of algorithm has very little effect on the size of the coefficients.Footnote 26

6 Conditional independence and sensitivity analyisis

One of the main assumptions of the propensity score approach is the conditional independence assumption (CIA).Footnote 27 The CIA might fail because of omitted variables that could play a big role in determining victimization and trust/participation in social groups. For example, some physical and behavioral traits might be important in explaining victimization but are not recorded in the data. For example, very skinny people might be more likely to be robbed because they might be easier targets. Or people that work at night could be more exposed to property crimes and violent crimes. Therefore, we propose a sensitivity analysis that evaluate how robust are our findings to the presence of such omitted variables. The CIA is not directly testable because we do not know what the trust/participation in social groups of the victimized people would have been had they not been victimized.

The sensitivity analysis relies on supposing the presence of an unobserved covariate that causes deviations from uncofoundness. In this paper we focus on the test proposed by Rosenbaum (2002). This model considers the relation between an unobserved variable and the treatment assignment.Footnote 28 The test evaluates what happens to the p-values of the statistical tests of no effect of the treatment when two individuals (i and j) with the same covariates differ in terms of the probability of receiving treatments. Formally, the probabilities, for each individual, of receiving treatment are: \( P_{i} = P_{x_{i}, u_{i}} = P(D=1 \mid x_{i}, u_{i})= F(\beta x_{i} + \gamma u_{i}) \), where \( x_{i} \) are the covariates and \( u_{i}\) the unobserved variable (Rosenbaum 2002). The bounds on the odds ratio that either individual will receive treatment are

\(e^{\gamma } \) is 1 if the two individuals obtained the same probability of being treated. If, instead, this is greater than one, for example 3, then they differ in the odds of receiving treatment by a factor of 3. Then a Mantel and Haenszel test is conducted under the null hypothesis of no treatment effect. The test tells what happens to the p-values of the ATT when \( e^{\gamma }\) increases. Moreover, it considers the situation of overestimation of the treatment effect, \( Q^{+}_{MH} \), and underestimation, \( Q^{-}_{MH}\). The first case is the most important to us because we assume that there could be a positive bias. Those that are victimized are more likely to participate in social organizations. We perform such tests for trust in other people, Other People, and participation in all groups, All Groups.

The tests for the specification with Victimization and Other People can be seen in Table 13. The study is insensitive to the presence of omitted variables. As predicted, \( Q^{-}_{MH} \) gives always significant ATTs. On the other hand, the results for All Groups show that the results are insensitive to a bias that would increase the odds of being victimized by 5% but sensitive to a bias that would lead to a 10% increase. The p-value of the ATT would then be positive again for \( e^{\gamma }=1.15\) and above (Table 14).Footnote 29

7 Conclusions

Social capital is one of the most powerful concepts of the social sciences. The study of its determinants is important for deepening our understanding of it. In the present paper, we move a step forward compared to the existing literature and consider the effect of victimization on two important dimensions: trust and participation in social groups. In order to explore this empirical question, we use individual data taken from all Latin American and Caribbean countries from 2004 until 2012 using LAPOP data. Our estimation technique is propensity score matching, because victimization could be seen as randomly assigned after controlling for various socio-economic variables. The results, in Table 6, clearly show that victimized people have lower levels of trust compared to non-victims. In particular, “treated” people have lower trust in other people and in institutions that directly manage law and enforcement. For example, a victim is about 6.5% less likely to trust the police compared to somebody who has not been victimized. These results are in line with recent work on this topic (Corbacho et al. 2015; Blanco 2013; Blanco and Ruiz 2013). However, compared to the existing literature, we focus on more countries and for a longer period of time. Moreover, we clearly distinguish between organizations involved in law enforcement management, such as the police, compared to others that are not, such as the media.

Besides the issue of trust, we also analyze how victimization affects participation in social groups. This relation has been largely unexplored in the literature. We use LAPOP data, which include questions on the frequency of participation in social organizations. In such a way we can take into consideration possible simultaneity issues between the treatment and outcome variables. Table 7 shows that victimized people increase their level of participation in social groups compared to non-victims. A victim of any type of crime is about 2.5% more likely to participate in All Groups, a dummy equal to one if the respondent participated in any of the following organizations: Religious, Community, Professional Organization, and Political Party. Such results could be explained through the stress buffer hypothesis (Cohen and Wills 1985). This theory states that people seek social support to cope with stressful periods, such as being a victim of crime. Moreover, we find that victims of property crime increase participation in social groups more than do victims of violent crime.

As a robustness check, we estimated the model using the Chilean victimization survey. Again, we find similar results: victimized people trust less than non-victims, but participate more in social organizations. Sensitivity tests, to the presence of omitted variables, reveal that the results are quite robust, especially for the model with trust.

In conclusion, this paper helps to analyze victimization from a different angle. On the one hand, we confirm that victimization reduces the stock of social capital by increasing mistrust in other people and organizations. On the other hand, the effect on participation in social organizations suggests that there is an increase in the stock of social capital. The positive effect on participation is a good thing. A forward looking public administrator should be aware of this and exploit such findings by coordinating and facilitating the creation of social groups. For example, the World Bank has a long history of promoting programs for the creation of social capital in developing countries (Vajjaa and Whiteb 2008). This would be beneficial to victims of crime, by reducing the time of “recovery” from such a stressful event, and reducing crime. As noted by McIlwaine and Moser (2001), in their study of Colombia and Guatemala, “social capital may be simultaneously eroded, fostered or reconstituted by violence, resulting in both positive and negative aspects of the phenomenon” [ibid, p. 966].

Notes

Interestingly, the work on adolescents by Wright and Fitzpatrick (2006) showed that social capital reduces crime, expect for sports and club participation. This result is important in the light of our results on social participation.

Also, there is an interesting study by Braakmann (2012) which analysed how victimization, and the beliefs of victimization, alter the behavior of people. In particular, victims (or potential victims) are more likely to arm themselves and increase the protection of their homes.

Or Putnam (1995, p. 6), who defined social capital as the “features of social organization such as networks, norms, and social trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit”.

In his 1994 study of Italy, Putnam et al. (1994) concentrated on civic engagement, which they proxied by voter turnout, newspaper readership, membership in choral societies, soccer clubs, and confidence in public institutions.

Even though self reported.

These authors used the post-traumatic growth hypothesis (Blattman 2009), instrumental concerns, and emotional and expressive motivations to justify increased participation. She used data from opinion polls such as the AmericasBarometer, Eurobarometer, Afrobarometer, and Asian Barometer. All these surveys ask whether the respondent had been a victim of crime in the previous twelve months. The author recognizes that in her work there are three threats to identification: reverse causation, neighborhood effects, and omitted variable bias. She considered whether prior political participation might be what was affecting the current participation, rather than its being a result of the victimization. To check this, past voting was introduced into the regression and also matching was employed, using that variable as a predictor of victimization so as to balance victims and non-victims in terms of their history of voting. The author found that victimization does not have a statistically significant effect on past voting except for the USA and Canada. Neither do the results change when controlling for local and national crime levels. Neighborhood factors are not the cause of either victimization or participation. The author also controlled for the sociability and outgoingness of the respondent, with LAPOP, but the results are hardly changed.

AmericasBarometer is a large household survey conducted in all the independent countries in the mainland North, Center, and South America. It also includes some Caribbean countries. This database, which is part of the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP), is mainly sponsored by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). However, it is also supported by the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), and universities such as Vanderbilt and Princeton, among others. The aim of this survey is to question people about democratic issues and behavior. It was first launched in 2004 when it covered eleven countries and it is repeated every other year. The latest available edition is 2012. Survey participants are voting age citizens and are interviewed in person, except for Canada and USA, where they responded on the Web. The survey uses a national probability sample design that takes into consideration characteristics such as location and ethnicity. Almost all the countries have around 1,500 individual respondents, except for a few countries. In general, this data is considered to be reliable, and has been used in several studies, such as the World Bank Governance Indicators.

Unless we consider burglary. Even in that case, a person that participates more in social groups is more likely to leave the house empty, which attracts more burglars.

Despite being confident on the identification strategy adopted, we cannot rule out completely that there might still be some degree of reverse causation. For example, let us suppose that there is no effect of victimization on participation in social organizations, but only one of participation on victimization. In such case we would incorrectly a positive effect where, in reality, there is not. We thank the anonymous referee for pointing this out.

Caliendo and Kopeinig (2008).

For this first stage regression, we also evaluated the use of other measures of income, such as middle or high income. Another candidate set of variables were the ones on ethnicity. Finally, we would have liked to include work-related variables, but these were available only from 2006.

Results are available upon request.

As a further exercise, we have checked the balancing properties for each country. For the large majority of countries and variables, we cannot reject the null hypothesis of statistical significant differences between treated and untreated.

Although in our study we consider only Catholic church, whereas Corbacho et al. (2015) focused on all types of organizations

It is worth recalling that participation in cooperatives has the highest coefficient but was not asked in all the waves. Therefore, it was not included in All Groups

For this wave, data is missing.

For example, in the case of property crime, all non-property crime victims have been excluded from the sample when estimating the ATT.

We did not report damage, rape, kidnapping because the number of “treated” individuals is very low.

For more information, consult the website of the Chilean Ministry of the Interior and Public Security.

2005 was a particularly important year for Chile, as it had general elections. However, this should not have an effect on our research question.

Given the richness of the questions on crime, here property crime is the sum of burglary, robbery with surprise, economic crime, and theft. Violent Crime includes assault, rape, and robbery with violence.

Carabineros and the PDI are two types of police.

The last option was “other” if they had not participated in any of the fourteen listed groups.

The acronym INE stands for the Chilean National Institute of Statistics.

This assumption states that we can remove the selection bias by controlling on an extensive set of control variables, which makes the treatment and control independent. Being victimized is assumed to be random for people with the same propensity score.

We follow the example of Becker and Caliendo (2007) and assume that the unobserved variable is binary.

This is a similar case to the one presented by Becker and Caliendo (2007).

References

Abadie A, Imbens GW (2006) Large sample properties of matching estimators for average treatment effects. Econometrica 74:235–267

Abadie A, Imbens GW (2009) Matching on the estimated propensity score, NBER Working Papers 15301, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc

Abadie A, Imbens GW (2011) Bias-corrected matching estimators for average treatment effects. J Bus Econ Stat 29:1–11

Algan Y, Cahuc P (2010) Inherited trust and growth. Am Econ Rev 100:2060–2092

Bateson R (2012) Crime victimization and political participation. Am Polit Sci Rev 106:570–587

Becker SO, Caliendo M (2007) Mhbounds-sensitivity analysis for average treatment effects. Technical Report, IZA Discussion Papers

Beyerlein K, Hipp JR (2005) Social capital, too much of a good thing? American religious traditions and community crime. Soc Forces 84:995–1013

Blanco LR (2013) The impact of crime on trust in institutions in Mexico. Eur J Polit Econ 32:38–55

Blanco L, Ruiz I (2013) The impact of crime and insecurity on trust in democracy and institutions. Am Econ Rev 103:284–288

Blattman C (2009) From violence to voting: war and political participation in Uganda. Am Polit Sci Rev 103:231–247

Braakmann N (2012) How do individuals deal with victimization and victimization risk? Longitudinal evidence from Mexico. J Econ Behav Organ 84:335–344

Buonanno P (2003) The socioeconomic determinants of crime. A review of the literature, Working Papers 63, University of Milan-Bicocca

Buonanno P, Montolio D, Vanin P (2009) Does social capital reduce crime? J Law Econ 52:145–170

Caliendo M, Kopeinig S (2008) Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. J Econ Surv 22:31–72

Carreras M (2013) The impact of criminal violence on regime legitimacy in Latin America. Latin Am Res Rev 48:85–107

Cassel J (1976) The contribution of the social environment to host resistance. Am J Epidemiol 104:107–123

Chilean Ministry of The Interor and Public Security, Encuesta Nacional Urbana de Seguridad Ciudadana (ENUSC) (2016). http://datos.gob.cl/datasets/ver/9926/. Accessed 8 March 2016

Cobb S (1976) Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom Med 38:300–314

Cohen S, Wills TA (1985) Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull 98:310

Coleman J (1994) Foundations of social theory. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Corbacho A, Philipp J, Ruiz-Vega M (2015) Crime and erosion of trust: evidence for Latin America. World Dev 70:400–415

Fernandez KE, Kuenzi M (2010) Crime and support for democracy in Africa and Latin America. Polit Stud 58:450–471

Glaeser EL, Laibson D, Sacerdote B (2002) An economic approach to social capital. Econ J 112:437–458

Guiso L, Sapienza P, Zingales L (2004) The role of social capital in financial development. Am Econ Rev 94:526–56

Keefer P, Knack S (1997) Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. Q J Econ 112:1251–1288

Knack S, Zak PJ (2001) Trust and growth. Econ J 111:295–321

Lederman D, Loayza N, Menendez AM (2002) Violent crime: does social capital matter? Econ Dev Cult Change 50:509–539

McIlwaine C, Moser C (2001) Violence and social capital in urban poor communities: perspectives from Colombia and Guatemala. J Int Dev 13:965–984

Putnam RD (1995) Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. J Democr 6:65–78

Putnam RD (2000) Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster, New York

Putnam RD, Leonardi R, Nanetti RY (1994) Making democracy work: civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Rosenbaum PR (2002) Observational studies, 2nd edn. Springer, New York

Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB (1983) The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 70:41–55

Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB (1985) Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. Am Stat 39:33–38

Rosenfeld R, Baumer EP, Messner SF (2001) Social capital and homicide. Soc Forces 80:283–310

Rubio M (1997) Perverse social capital: some evidence from Colombia. J Econ Issues 31:805–816

Skaperdas S (2011) The costs of organized violence: a review of the evidence. Econ Gov 12:1–23

Soares RR (2006) The welfare cost of violence across countries. J Health Econ 25:821–846

Vajjaa A, Whiteb H (2008) Can the World Bank build social capital? The experience of social funds in Malawi and Zambia. J Dev Stud 44:1145–1168

Valdivieso P, Villena B (2014) Opening the black box of social capital formation. Am Polit Sci Rev 108:121–143

Wright DR, Fitzpatrick K (2006) Social capital and adolescent violent behavior: correlates of fighting and weapon use among secondary school students. Soc Forces 8:1435–1453

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Pazzona, M. Do victims of crime trust less but participate more in social organizations?. Econ Gov 21, 49–73 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-019-00227-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-019-00227-1