Abstract

The aim of the present study was to investigate associations between internalizing and externalizing symptoms and deficits in executive functions (EF) as well as to examine the overall heterogeneity of EFs in a sample of preschool children attending a psychiatric clinic (n = 171). First, based on cut-off points signifying clinical levels of impairment on the parent-completed Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), children were assigned into groups of internalizing, externalizing, combined or mild symptoms and compared to a reference group (n = 667) with regard to day care teacher ratings of EFs on the Attention and Executive Function Rating Inventory-Preschool (ATTEX-P). Second, latent profile analysis (LPA) was employed to identify distinct subgroups of children representing different EF profiles with unique strengths and weaknesses in EFs. The first set of analyses indicated that all symptom groups had more difficulties in EFs than the reference group did, and the internalizing group had less inhibition-related problems than the other symptom groups did. Using LPA, five EF profiles were identified: average, weak average, attentional problems, inhibitory problems, and overall problems. The EF profiles were significantly associated with gender, maternal education level, and psychiatric symptom type. Overall, the findings suggest that the comparison of means of internalizing and externalizing groups mainly captures the fairly obvious differences in inhibition-related domains among young psychiatric outpatient children, whereas the person-oriented approach, based on individual differences, identifies heterogeneity related to attentional functions, planning, and initiating one’s action. The variability in EF difficulties suggests that a comprehensive evaluation of a child’s EF profile is important regardless of the type of psychiatric symptoms the child presents with.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to a contemporary definition, EFs include basic functions related to inhibition of responses and distracting stimuli, working memory, and flexible shifting of attention or response-set [1, 2] as well as more complex processes such as planning and use of strategies [3, 4]. EF difficulties are often present in children with different kinds of psychiatric problems [5,6,7,8]. Already in the preschool period, EF difficulties are common among young children referred to psychiatric care [9]. Previous studies examining the link between EFs and psychiatric symptoms have provided inconsistent findings and the majority of studies have focused on older children. In addition, only a few studies have examined the heterogeneity of EFs in mixed clinical groups on the level of individual variation instead of averaging across diagnostic/symptom groups.

EFs are known to follow a protracted course of development that parallels the relatively slow maturation of the prefrontal cortex [10], an essential part of the neuronal circuitry responsible for EFs. The basic forms of EF, particularly inhibition and working memory, start to develop in infancy [11]. Especially, the preschool period (roughly the ages of 3–6 years) is characterized by rapid development of EFs [11, 12]. During this time, gender differences are often evident, as girls tend to be ahead of boys in the development of EFs [13, 14]. Environmental factors also contribute to the development of EFs: especially, higher parental education and socioeconomic status have been associated with better EFs [14,15,16]. EFs are crucial for adjustment across all aspects of life. For children, EFs are important for school success [17, 18] and socioemotional competence [19]. They are also predictive of many outcomes, such as health and personal finances, later in life [20].

EF difficulties can be assessed with performance-based tests and behavioral rating scales. Performance-based tasks are administered under highly standardized conditions and yield information about the cognitive capacities related to EFs, while behavioral measures are based on observations of the child’s EF behaviors in daily situations. Although the typically used performance-based measures may give a detailed account of the child’s EF capacities, they do not correspond to the multifaceted and dynamic nature of real-world situations [21]. Thus, in addition to performance-based measures, rating scales should be used to provide clinical indicators of the child’s functional ability related to EF competence and difficulties.

Typically, the relations between EF difficulties and psychiatric symptoms have been examined on the level of different diagnostic or externalizing/internalizing symptom groups. Externalizing symptoms refer to problems directed primarily outwards and involving conflict with others, such as aggression, conduct problems, and hyperactivity [22]. Most studies examining EF deficits related to externalizing symptoms in school-aged children have used performance-based measures. In these studies, deficits in inhibition, working memory and set shifting have consistently been found [23,24,25,26]. Parent and teacher ratings of EFs in school-aged children with externalizing symptoms have generally revealed wide-ranging difficulties, with an emphasis on difficulties in inhibition and working memory [15, 27, 28]. Accordingly, preschool children with externalizing symptoms have been found to have inhibitory deficits and, although somewhat less consistently, deficits in working memory and set shifting when examined using performance-based measures [7, 29]. Parent [30, 31] and teacher ratings [32, 33] of EFs have revealed broad difficulties in the everyday environment for these young children.

Internalizing symptoms refer to inward-directed problems, such as anxiety, depression, withdrawal, and somatic complaints [22]. A limited amount of studies has examined EFs in children with internalizing symptoms/disorders. In a meta-analysis concerning depressed children and adolescents, impairments in interference control, planning, working memory, shifting, and phonemic and semantic verbal fluency were found [8]. Recent empirical evidence indicates that a deficit in cognitive flexibility, referring to the ability to shift attention and response-set, may specifically relate to internalizing symptoms [34]. However, many studies have not found EF deficits in depressed children and adolescents [35], and the extent to which the variability reflects methodological differences in sample selection, inclusion criteria, and EF tasks is unclear.

The relations between EFs and internalizing symptoms among preschool children are even less studied. Skogan et al. [36] found broad EF difficulties in 3-year-old children with an internalizing disorder (anxiety) when using the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function–Preschool Version (BRIEF-P) to assess EFs. Eisenberg et al. [32] utilized both performance-based and rating scale measures with multiple informants in examining executive control in 4–8-year-old children. They reported that the children high in internalizing symptoms were rated as less impulsive and lower in attentional control than the control children, but similar with regard to inhibitory control. Finally, some recent longitudinal studies have found that preschool EF difficulties, especially in inhibition and flexibility, are related to internalizing symptoms in the elementary school years [37, 38].

The conflicting evidence on EF dysfunction in children with internalizing and externalizing symptoms points towards the heterogeneity of EF abilities within these clinical groups and even within single disorders. Person-oriented methods, such as cluster analysis or latent profile/class analysis, provide a useful approach in such instances by allowing the empirical identification of distinct subgroups based on different indicators, such as EF abilities. In contrast to the variable-oriented approach, the focus is on the individual instead of the group and on the configuration of information instead of the single variable representing a given construct [39]. The theoretical roots of the person-oriented approach can be found in the holistic–interactionist paradigm formulated by Bergman and Magnuson [40], which highlights the importance of studying individuals as organized wholes based on their unique patterns of characteristics. The basic tenet is that, despite the structure and dynamics of behavior being partly unique to individuals, there is still lawfulness to development, and often only a rather small number of typical patterns is enough to describe it adequately [40]. From a methodological perspective, the person-oriented approach may allow avoiding the pitfalls of data aggregation that often do not do justice to the individual nor to the possible subpopulations within the sample [41].

Only a few studies have taken a person-oriented route and addressed the heterogeneity of EFs by identifying subgroups within samples of children with psychiatric symptoms. Kavanaugh et al. [42] examined the presence of neurocognitive subgroups within a sample of child psychiatric inpatients using cluster analysis. Their study included measures of EFs as well as other cognitive functioning. Four subgroups—intact, global dysfunction, organization/planning dysfunction, and inhibition-memory dysfunction—were found. Using BRIEF scales and the Statue subtest from NEPSY as EF indicators, Dajani et al. [43] identified average, above average and impaired subgroups of EFs in a sample consisting of typically developing children and children with neurodevelopmental disorders. They concluded that the nature of EFs is dimensional in children, because no differences in strengths and weaknesses between the subgroups were found. Therefore, it remains uncertain whether subgroups displaying not only quantitative, but also qualitative differences in EFs can be found in clinical groups of children via person-oriented methods.

The aim of the present study was to investigate inter child variability in EF difficulties among clinically referred children. This was done in two stages. First, we followed a traditional group comparison approach by examining the EF difficulties of children classified into groups according to their level of internalizing and externalizing symptoms. We predicted that the groups with mainly externalizing and both externalizing and internalizing symptoms would have elevated scores (indicating more problems) in all EF domains in comparison with controls. Due to some previous studies suggesting that particularly flexibility difficulties may be closely related to internalizing symptoms, we expected that the internalizing group would have more problems than the reference group in, at the least, shifting attention. The externalizing group was expected to have more difficulties than the internalizing group in, at the least, impulsivity and motor hyperactivity. The aim of the second stage was to derive subgroups of children with distinct EF profiles based on individual-level variation in EFs. Because no previous study that we are aware of has investigated EF profiles in a mixed clinical sample of preschool children, we took an exploratory approach without specific hypotheses about the outcome. Finally, subgroup differences in age, gender, maternal education level, and internalizing/externalizing symptoms were investigated.

Methods

Participants

The clinical group consisted of children recruited from two psychiatric outpatient clinics evaluating and treating preschool children at Helsinki University Hospital, Child Psychiatry Unit. The data were collected between March 2015 and May 2017. Inclusion criteria were (a) child’s age between 4 and 7 years, (b) Finnish-speaking parents, and (c) child attending day care. Overall, 315 patients visited the two clinics during data collection, and 252 of them met the inclusion criteria and received the Attention and Executive Function Rating Inventory-Preschool (ATTEX-P) and CBCL questionnaires. Of them, 171 (67.8%) families returned both the study questionnaires. Due to lacking information about the non-participants, we were unable to perform a direct comparison between the participants and non-participants. However, the characteristics of the present sample were in line with the previous reports indicating high rates of comorbidity, a higher prevalence of boys than girls, and an overrepresentation of low maternal education among pre-school children referred to psychiatric care [44, 45]. The present sample was heterogeneous in terms of diagnoses: 39 (22.8%) children were diagnosed with ADHD, 29 (17.0%) children were diagnosed with either conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder, and diagnoses for other neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism spectrum, learning, speech, and motor system disorders were also frequent (n = 34, 19.9%) [9]. 34 (19.9%) children had at least one Z-diagnosis describing psychosocial stress. In addition, 69 (40.4%) children had an unspecified neurodevelopmental diagnosis (F88 or F89), reflecting the fact that the psychiatric evaluation was not yet completed.

The reference group consisted of children who took part in the ATTEX-P [46] standardization study between August 2014 and May 2015. The data were collected from 28 day care units in a medium-sized city in the southern part of Finland. Inclusion criteria were (a) age between 4 and 7 years and (b) Finnish-speaking parents. Families delivered the ATTEX-P questionnaires to the day care units, and the questionnaires of 709 children were returned. The reference group was well representative of the Finnish population in terms of children’s gender and mothers’ educational-level distributions [47, 48].

Of the 880 participants, 8.3% had one or more missing observations on the ATTEX-P. In the clinical sample, a maximum of one value per participant was missing on any given scale, and all of the missing values were imputed by calculating the participant’s mean value for the scale items. The missing values for maternal education level (n = 3) in the clinical sample were replaced with the mode value of maternal education level within the participant’s respective symptom group. In the reference sample, participants with any missing values on the ATTEX-P (n = 24) or maternal education level (n = 19) were omitted from the analyses. These procedures resulted in a final sample of 838 participants, 667 in the reference group and 171 in the clinical group.

Measures

Executive functions

The ATTEX-P [46] is a 44-item rating scale designed for assessing EF behavior of children aged 4–7 years in a day care environment. ATTEX-P is an adaptation of the ATTEX rating scale for school-age children [15] and covers a wide range of behaviors reflecting both basic and complex EF processes. The day care teacher rates the frequency of EF difficulties on a three-point scale (0 = not a problem, 1 = sometimes a problem, and 2 = often a problem). The questionnaire yields a total score as well as scores for nine clinical subscales: (1) distractibility (5 items), (2) impulsivity (10 items), (3) motor hyperactivity (5 items), (4) directing attention (5 items), (5) sustaining attention (4 items), (6) shifting attention (4 items), (7) initiative (3 items), (8) planning (3 items), and execution of action (5 items). Higher scores on the scales indicate more problems. The total score and the subscales have demonstrated good internal consistency (ranging from 0.73 to 0.94), test–retest reliability (ranging from 0.81 to 0.94), and convergent validity (correlations with EF items in a school readiness questionnaire ranging from 0.49 to 0.75) [46]. Total or scale scores at or above the 90th percentile are considered to indicate clinically relevant deficits in EF behavior.

Emotional and behavioral problems

Parent ratings of the child’s emotional and behavioral problems on the Child Behavior Checklist/1.5–5 (CBCL) [22] were used for grouping participants into subgroups according to externalizing and internalizing symptoms. CBCL is a parent-report form of a widely used questionnaire measuring children’s behavioral and emotional problems. The form contains 99 problem items rated on a three-point scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, 2 = very true or often true). The questionnaire has demonstrated good reliability and validity [22] as well as generalizability across 23 societies [49]. The broadband internalizing problem scale consists of the following four symptom scales: emotionally reactive; anxious/depressed; somatic complaints; and withdrawn. The broadband externalizing scale contains the remaining symptoms scales: attention problems and aggressive behavior.

Background information

Information on age, gender, and maternal education level was collected from parents via a short questionnaire.

Data analyses

Symptom group comparisons

For the symptom group comparisons, subgroups of children from the clinical sample were formed based on parent reports on the CBCL internalizing problems and externalizing problems scales. First, T scores of the raw scale scores were computed using ADM (9.1) scoring software. Children whose score reached the clinically significant problem level (T score > 63) on the Internalizing Problems or Externalizing Problems scale, but not on both scales, were included in the groups of children showing either internalizing symptoms (INT) or externalizing symptoms (EXT). Children with T scores greater than 63 on both scales were included in the combined group (COMB), and children with T scores below 63 on both scales were included in a group showing mild symptoms (MILD) (Table 1).

Using SPSS 24, the symptom groups were compared to the reference group in EF variables. Overall group differences on the ATTEX-P total score were analyzed with ANCOVA, and differences in the scale scores were examined with MANCOVA, followed by separate ANCOVAs for the scale scores and pairwise comparisons for group contrasts. A Bonferroni-corrected significance level p < 0.005 was applied in the pairwise comparisons to account for the 10 comparisons. Variables representing age, gender, and maternal education level were included as covariates in all analyses. The effect sizes are reported as partial eta squared (\(\eta_{\text{p}}^{2}\); small < 0.06, medium 0.06–0.13, large ≥ 0.14) for the MANOVA and ANOVA analyses and as Cohen’s d (small < 0.50, medium < 0.80, large ≥ 0.80) for the pairwise comparisons [50].

Latent profile analysis (LPA)

Raw ATTEX-P scale scores were standardized according to the reference group to make the scales comparable to each other as well as to the level of typical development. Then, using Mplus 8.1 [51], models with different numbers of latent groups were fitted using the maximum likelihood method with robust standard errors as the estimation method. Only means were allowed to vary between groups. Different statistical criteria were considered when choosing the best-fitting model: Akaike’s information criteria (AIC) and Bayesian information criteria (BIC) are model evaluation criteria that take into account model fit and parsimony. The model with the lowest value is preferred. Vuong–Lo–Mendell–Rubin likelihood ratio (VLMR), Lo–Mendell–Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio (LMR), and bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT) assess relative model fit by comparing a model with k groups to one with k − 1 groups, with a p value < 0.05 suggesting significant improvement in model fit. In addition, entropy, subgroup sample sizes, and overall model interpretability were evaluated when choosing the best model. Entropy is a standardized measure of the certainty of assigning participants into groups based on their model-derived posterior probabilities. The value of entropy ranges between 0 and 1, with higher values indicating clearer group delineation [52]. To ensure that the best log-likelihood value of each model did not reflect a local solution, 500 starting values were used, and the replication of the best log-likelihood was checked for each model. When interpreting the profiles, mean scores at or above the 90th percentile were considered to imply clinically significant impairment on a given scale, in accordance with the norms of ATTEX-P [46].

In the second phase, participants were assigned to groups based on their most likely profile membership. The relationship between group membership and background variables, including gender, age, and maternal education level, was examined via cross tabulation and \(x^{2}\) tests. If the expected cell counts were less than 5 in 20% or more of the cells, exact tests were used. In addition, cross tabulation of the symptom groups with the person-oriented EF subgroups was performed to examine whether internalizing, externalizing, combined or mild symptoms were over- or underrepresented in the EF subgroups.

Results

Background characteristics of the symptom and reference groups

The means and standard deviations of the groups in demographic variables are displayed in Table 1. The groups differed significantly in gender ratio, X2(4) = 27.78, p < 0.001, with the COMB group including more boys than the reference group, X2(1) = 18.45, p < 0.001. The groups also differed in terms of age, F(4, 833) = 6.25, p < 0.001, \(\eta_{\text{p}}^{2}\) = 0.03, with the COMB group including younger children than the reference group (p = 0.001). Although the groups also differed in maternal education level, X2(4) = 16.24, p = 0.003, significant differences in column proportions between specific symptom groups were not found after adjusting for 10 group comparisons.

EF difficulties in the symptom and reference groups

Variables representing child’s age, gender, and maternal education level were included as covariates in all group comparisons. The groups differed from one another in the total EF score, F(4, 830) = 66.84, p < 0.001, \(\eta_{\text{p}}^{2}\) = 0.24. Pairwise comparisons revealed that all symptom groups had a higher total score than the reference group, with all p values < 0.001 and d ranging between 0.91 and 1.66. No significant differences between the symptom groups in the total EF score were found; however, the effect size for the difference between the INT and the EXT groups was close to large (d = 0.75), indicating more EF problems overall in the EXT group (M = 46.19, SD = 12.86) than in the INT group (M = 29.38, SD = 20.92). The groups differed from one another also in the scale scores, Wilks’s lambda = 0.71, F(36, 3082) = 8.38, p < 0.001, \(\eta_{\text{p}}^{2}\) = 0.08. ANCOVAs showed differences for each scale (Table 2). Pairwise comparisons revealed that all of the symptom groups had higher scores than the reference group on eight of the nine scales (p values ranging between < 0.001 and 0.039, d ranging between 0.66 and 1.68). On the motor hyperactivity scale, the difference between the REF and INT groups was not significant (p = 0.066, d = 0.56). The symptom groups differed from one another on impulsivity, with the INT group having a lower score than the EXT (p = 0.009, d = 1.00), COMB (p = 0.035, d = 0.70), and MILD (p = 0.030, d = 0.71) groups. On motor hyperactivity, the INT group had a lower score than the EXT (p = 0.003, d = 1.09) and COMB (p = 0.036, d = 0.70) groups. Of the insignificant differences between the INT and the EXT groups, the effect sizes for distractibility (d = 0.79), execution of action (d = 0.75), and sustaining attention (d = 0.69) were substantial, indicating more EF problems in the EXT than in the INT group in these domains. On the remaining scales (directing attention, shifting attention, initiation, and planning), the effect sizes for the insignificant differences between the INT and the EXT groups were small, with d ranging between 0.07 and 0.26.

EF difficulties in the person-oriented subgroups

A summary of LPA model fit indices is presented in Table S1 in Supplementary Materials. The BIC reached its lowest value in a five-group model, indicating an optimal solution. The AIC suggested six or more groups to be the preferred solution. Out of the comparative model fit indices, the BLRT suggested each consecutive model above a one-group model to provide a significant improvement in fit. The LMR and the VLMR indicated that four would be the maximum number of groups to consider. Thus, the statistical criteria gave support for models with four, five, and six groups. We rejected the six-group solution, because the sample size was too small in one subgroup (n = 9) and due to problems with interpretation. Both the four- and five-group solutions had adequate sample sizes in each subgroup as well as high entropy (0.93 and 0.92, respectively). We decided to prioritize the BIC, because it has been shown to perform better in the case of a small overall sample size and continuous indicator variables [53]. In addition, further analyses relating psychiatric symptoms to group membership provided support for the external validity of both the groups that were merged into one in the four-group model. Therefore, we chose the five-group model.

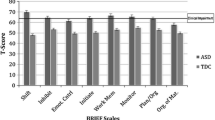

EF profiles of the five obtained subgroups groups are shown in Fig. 1. The first group (n = 29, 17%), named average, had average EF abilities across all domains. On no indicator did this group perform worse than the reference group, and in directing attention, their performance was nearly half a standard deviation below the reference group (i.e., their performance was better). The second group (n = 37, 22%) had slightly below average abilities on all EF indicators and was named weak average. Despite a mild elevation on the Initiation scale (0.97 standard deviations above the typical level), they did not have clinically relevant impairment in any EF domain. The third group (n = 25, 15%) had clinically relevant deficits in all EF domains except in motor hyperactivity. Due to not having high motor hyperactivity but showing severe deficits in attention-related domains, especially in shifting attention, this group was named attentional problems. The fourth group (n = 42, 25%) exhibited a profile that was somewhat of a mirror image to the third group. These children had particularly high motor hyperactivity, but showed no clinically significant deficits in directing or shifting attention nor in initiating behavior and was named inhibitory problems. The fifth group (n = 38, 22%) had clinically relevant and severe deficits across all EF domains and was thus named overall problems.

Significant mean differences between the groups on the EF scale scores were found, Wilks’s lambda = 0.03, F(36, 593) = 27.48, p = < 0.001, \(\eta_{\text{p}}^{2}\) = 0.60. As presented in Table S2 in the Supplementary Materials, the groups differed significantly from one another on all scales.

Background characteristics and psychiatric symptoms in the person-oriented subgroups

The results of the cross tabulation of the EF subgroups and background characteristics are presented in Table 3. The EF subgroups did not differ in terms of age, F(4, 166) = 0.60, p = .595, \(\eta_{\text{p}}^{2}\) = 0.02. A significant association between group membership and gender was found, X2(4) = 31.14, p < .001. The adjusted residuals suggested that there were more boys than expected in the inhibitory problem group (adj. res. = 3.2), and more girls than expected in the average (adj. res. = 4.4) and weak average (adj. res. = 2.2) groups. The groups also differed in terms of maternal education level, X2(4) = 15.63, p = .004. Low maternal education was overrepresented in the inhibitory problem group (adj. res. = 2.6) as compared to the other groups, and high maternal education was overrepresented in the average and weak average groups (adj. res. = 2.3 and 2.2, respectively).

Cross tabulation of the EF and symptom groups was conducted to examine whether clinically significant levels of internalizing, externalizing, combined, or mild symptoms would be over- or underrepresented in certain EF subgroups (Table 3). Differences between the EF subgroups in symptom type were found (p = 0.005, Fisher’s exact test). Externalizing symptoms were overrepresented in the inhibitory problem group (adj. res. = 3.7), and internalizing symptoms were overrepresented in the weak average group (adj. res. = 2.6), and mild symptoms were overrepresented in the average group (adj. res. = 2.0).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate EFs among preschoolers with psychiatric symptoms. First, we followed a traditional approach of comparing children classified into groups based on their level of internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Groups of children with internalizing, externalizing, combined, or mild symptoms were compared to a reference group and to one another on the ATTEX-P total and scale scores. Second, we further examined the heterogeneity of EFs within the clinical sample using a person-oriented approach of empirically identifying subgroups of children showing distinct EF profiles. Associations between the subgroups and different indicators, including gender, age, maternal education, and psychiatric symptoms, were then examined to understand differences between the subgroups also beyond EFs.

When controlling for gender, age, and maternal education, all of the symptom groups differed from the reference group in nearly all EF domains, suggesting that, overall, young psychiatric outpatients tend to demonstrate poorer EF abilities than their typically developing peers regardless of their type of emotional and behavioral symptoms. The broad EF problems of the preschoolers with mainly externalizing and both externalizing and internalizing symptoms were in accordance with our hypotheses and similar to previous studies using EF rating scales [30, 32, 33, 36]. In addition, in accordance with our hypotheses, the children with internalizing symptoms had more problems in shifting attention than those in the reference group. However, they had more problems than the reference group in nearly all other EF domains as well, indicating that their EF difficulties in the day care environment were widespread. In motor hyperactivity, the difference was not significant, yet the moderate effect size suggests that children with internalizing symptoms may have more problems with hyperactivity than children in general do. The findings concerning children with internalizing symptoms resemble those of Skogan et al. [36], who discovered that anxious preschoolers scored higher than reference children on all scales of the BRIEF-P. In addition, in accordance with our findings, Cataldo et al. [54] found increased levels of behavioral impulsivity in a clinical sample of school-aged depressed children. In contrast to our findings, Eisenberg et al. [32] found, in a normative sample, that children with internalizing symptoms were rated as less impulsive than controls were and concluded that these children seem to exhibit an “overcontrolled” style of regulation. The fact that the children with internalizing symptoms in our clinical sample were rated as more impulsive than the reference children, albeit to a lesser degree than the children with externalizing, combined, or even mild symptoms, could reflect differences in samples (clinical vs. normative). Somewhat different patterns of everyday EFs may be expected for children with internalizing symptoms within clinical and non-clinical settings, particularly in terms of impulsivity, highlighting the need to study the relationship between EFs and internalizing symptoms at different levels of symptom severity and comorbidity.

Differences between the symptom groups emerged in impulsivity and motor hyperactivity. The children with internalizing symptoms showed less problems in these aspects of EFs than other children with psychiatric symptoms, and as expected, the difference was most substantial between the internalizing and externalizing groups. The substantial effect sizes for differences between the internalizing and externalizing groups in distractibility and execution of action may indicate that differences in these EF domains exist as well, with the children high in externalizing symptoms having more problems. In accordance with the findings of Eisenberg et al. [32], the children with both internalizing and externalizing symptoms had similar EF difficulties as the children with mainly externalizing symptoms. Thus, high levels of combined symptoms do not seem to make children more or less prone to EF difficulties than having high externalizing symptoms only.

Apart from the differences in impulsivity and motor hyperactivity, the symptom groups had similar difficulties in most EF domains, suggesting that clinically referred children have more similarities than differences in terms of EF behaviors. However, it could also indicate that the classification of children based on their symptoms did not ideally capture the full heterogeneity of EFs present in the sample. By further investigating the latter option using LPA, five profiles were discerned, with one group of children showing average EF behaviors, one group showing weak average EF behaviors, and three groups showing major EF difficulties with either attentional problems, inhibitory problems, or problems in all aspects of the EFs evident (Fig. 1). The identification of qualitatively different subgroups implies that, in addition to the high overall rates of EF impairment present among young child psychiatric outpatients [9], considerable heterogeneity also exists. Importantly, examining individual-level differences in EFs seemed to provide more fine-grained information than did the comparisons of internalizing/externalizing groups. The person-oriented approach seemed to better display inter child differences in multiple different domains of EFs, such as in attentional functions, initiating action, and planning.

The finding that the subgroups differed not only in the severity, but also in the pattern of difficulties is in contrast with the findings of Dajani et al. [43], who identified only severity differences in the EF profiles of children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Importantly, a portion of the children—those belonging to the average and weak average groups—did not demonstrate clinically relevant impairment in any EF domain. Likewise, Kavanaugh et al. [42] reported that 68% of their sample of child psychiatric inpatients displayed neurocognitive impairment. They concluded that neurocognitive weaknesses are not present in all children with severe psychiatric disorders. Similarly, among preschool-aged psychiatric outpatients, a notable subgroup does not seem to display clinically significant EF impairment in the day care context.

In addition to not showing clinically significant EF impairment, the children with an average EF profile were characterized by mild psychiatric symptoms (below clinical levels of both internalizing and externalizing symptoms). The reason for the psychiatric referral of these children could be primarily related to other problems than the child’s behavior, e.g., crisis in the family or parenting issues. A weak average profile was associated with clinically significant levels of internalizing symptoms (with problems in initiation slightly standing out). A profile marked by inhibitory problems, evident as high levels of impulsivity, distractibility, and hyperactivity, was associated with clinically significant levels of externalizing symptoms, which is in accordance with the previous literature suggesting that children with externalizing symptoms have particular problems with respect to inhibition [31, 33, 36].

Neither high nor low internalizing and/or externalizing symptoms were related to the profiles marked by attentional or overall problems. The children showing these profiles may have psychiatric symptoms that are not well captured by the internalizing/externalizing domains of the CBCL, e.g., attentional symptoms related to the inattentive subtype (ADHD-I) and/or social and communicative symptoms characteristic of autism spectrum problems. Among school-aged children, inattention and autism-related problems have been considered as separate domains of psychopathology alongside with internalizing, externalizing, and non-specific domains [55]. Previous literature suggests that children with ADHD-I tend to have difficulties in many aspects of EFs, but less in response inhibition [56, 57], similar to the pattern of EFs shown by the attentional problem group. This group was also the most impaired in shifting attention, and deficits in set shifting or cognitive flexibility have been associated with autism spectrum problems [58, 59]. In addition, the profile marked by severe overall EF problems may be more related to the severity and chronicity of psychiatric symptoms than to any specific symptom type per se [34]. Similar EF problems have previously been indicated in children with both inattentiveness and hyperactivity [57] as well as autism spectrum problems [60, 61], and in comorbid groups [43].

In addition to psychiatric symptom type, EF subgroup membership was significantly associated with gender and maternal education level. The group with inhibitory problems was characterized by low maternal education and a high prevalence of boys. The groups with average and weak average EF profiles were characterized by a high prevalence of girls and high maternal education. This is in accordance with the previous findings suggesting that, in the preschool period, boys tend to display more EF difficulties than girls do [13, 14]. In addition, the previous studies have linked higher parental education to better EF abilities in children [14, 15]. Our findings indicate that low maternal education is particularly pronounced in a subgroup of children showing inhibitory problems and not necessarily in the subgroup showing the highest overall levels of EF impairment. Externalizing symptoms were also pronounced in the inhibitory problem group, thus underlining the existence of a subgroup of preschoolers among whom cognitive, socioemotional, and environmental risk factors tend to accumulate.

The relationship between psychopathology and EF difficulties has been studied in methodologically diverse ways, which may explain some of the variability in results and make comparisons between studies difficult. In terms of the present study, it should be kept in mind that rating scales generally show only low-to-moderate correlations with performance-based measures, highlighting the fact that they tap somewhat different underlying constructs [62]. Ideally, future studies should utilize both performance-based measures and rating scales to validate the present findings. In addition, children’s emotional and behavioral problems were evaluated by parents and EF behaviors by day care teachers. It is widely known that raters across different situations generally have low agreement [63], as different environments (day care, home) have different expectations and bring out different aspects of the child’s behavior. Parents may be at an advantage to evaluate their children’s internalizing problems, because these problems may not come out so easily in the day care or school environment [64]. In addition, teacher ratings of children’s EFs might tap an aspect of the EF construct that has particular bearings on important school-related outcomes [65]. Overall, the utilization of different informants to report on different aspects of children’s behavior can be seen as a strength of the present study, as it eliminates the possibility that the results would be due to same rater bias.

Some other limitations should also be noted. First, some overlap between the rating scale items measuring externalizing symptoms and EFs—mainly impulsivity, motor hyperactivity, and sustaining attention—exist and can artificially magnify the relationship between externalizing symptoms and the mentioned EF behaviors. Although the overlap is small, as the externalizing problems scale of the CBCL is mostly comprised of items assessing aggressive behavior, it should be taken into account when interpreting the results. Second, small symptom group sizes reduced the power to find significant effects, and therefore, effect sizes were examined in addition to p values for all pairwise comparisons. The clinical sample as a whole was also somewhat small for LPA. Replications of the group solution with larger clinical samples are needed to justify the existence of the subgroups identified here. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of the present study does not allow any conclusions to be drawn about the direction of relationships. It remains to be investigated whether primary EF problems can place a child at risk for the development of psychiatric problems or the other way around, or whether the two kinds of problems reflect a common underlying vulnerability and thus often coexist.

A strength of the present study was its utilization of two complementary methodological approaches. Despite providing useful information on a group level, a drawback of the variable-oriented approach is its assumption of uniformity of the groups. For instance, the externalizing group may include children with very different kinds of symptoms, as some may have problems related to aggressive behavior and others mainly to hyperactivity. Thus, the EF profiles of these children may markedly differ from one another. In this study, the person-oriented approach was useful in revealing such heterogeneity within the internalizing/externalizing groups. For instance, although the internalizing group showed more EF problems overall than the reference group, the majority of the children with internalizing symptoms had average or close to average EF behaviors in all domains. However, approximately one-third had severe problems, and in psychiatric care, the identification of these children via screening is important. In addition, a benefit of the person-oriented approach is its ability to find underlying EF subgroups that may not correspond to any known diagnostic or symptom groups. If future studies validate these subgroups, EF interventions specifically targeted at children with matching EF profiles could be designed.

The present findings suggest that clinically referred preschool children, regardless of the type of psychiatric symptoms they have, tend to display more everyday EF problems than typically developing children do. Children with internalizing symptoms tend to have less difficulties in inhibiting undesirable behaviors than other children with psychiatric symptoms do, but beyond that, the diagnostic groups show little difference. Heterogeneity in other EF behaviors, including attention-related functions, planning and acting on one’s own initiative becomes apparent when EF profiles are identified based on individual variation in EFs. Clinically, the present findings imply that the screening of EF difficulties is important regardless of a child’s psychiatric symptoms. In case signs of EF difficulties arise, a comprehensive evaluation of the child’s EF profile is important, so that the EF strengths and weaknesses may be identified and considered when planning for intervention.

References

Miyake A, Friedman NP (2012) The nature and organization of individual differences in executive functions: four general conclusions. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 21:8–14

Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, Wager TD (2000) The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: a latent variable analysis. Cogn Psychol 41:49–100

Diamond A (2012) Executive functions. Annu Rev Psychol 64:135–168

Nigg JT (2017) Annual research review: on the relations among self-regulation, self-control, executive functioning, effortful control, cognitive control, impulsivity, risk-taking, and inhibition for developmental psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 58:361–383

Kusché CA, Cook ET, Greenberg MT (1993) Neuropsychological and cognitive functioning in children with anxiety, externalizing, and comorbid psychopathology. J Clin Child Psychol 22:172–195

Pennington BF, Ozonoff S (1996) Executive functions and developmental psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 37:51–87

Schoemaker K, Mulder H, Deković M, Matthys W (2013) Executive functions in preschool children with externalizing behavior problems: a meta-analysis. J Abnorm Child Psychol 41:457–471

Wagner S, Müller C, Helmreich I, Huss M, Tadić A (2015) A meta-analysis of cognitive functions in children and adolescents with major depressive disorder. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 24:5–19

Huhdanpää H, Klenberg L, Westerinen H, Bergman PH, Aronen ET (2018) Impairments of executive function in young children referred to child psychiatric outpatient clinic. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 24:95–111

Gogtay N, Giedd JN, Lusk L, Hayashi KM, Greenstein D, Vaituzis AC, Nugent TF, Herman DH, Clasen LS, Toga AW, Rapoport JL, Thompson PM (2004) Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci 101:8174–8179

Garon N, Bryson SE, Smith IM (2008) Executive function in preschoolers: a review using an integrative framework. Psychol Bull 134:31–60

Montroy JJ, Bowles RP, Skibbe LE, McClelland MM, Morrison FJ (2016) The development of self-regulation across early childhood. Dev Psychol 52:1744–1762

Klenberg L, Korkman M, Lahti-Nuuttila P (2001) Differential development of attention and executive functions in 3- to 12-year-old Finnish children. Dev Neuropsychol 20:407–428

Sherman EMS, Brooks BL (2010) Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function-Preschool Version (BRIEF-P): test review and clinical guidelines for use. Child Neuropsychol 16:503–519

Klenberg L, Jämsä S, Häyrinen T, Lahti-Nuuttila P, Korkman M (2010) The Attention and Executive Function Rating Inventory (ATTEX): psychometric properties and clinical utility in diagnosing ADHD subtypes. Scand J Psychol 20:407–428

St. John AM, Kibbe M, Tarullo AR (2019) A systematic assessment of socioeconomic status and executive functioning in early childhood. J Exp Child Psychol 178:352–368

Best JR, Miller PH, Naglieri JA (2011) Relations between executive function and academic achievement from ages 5 to 17 in a large, representative national sample. Learn Individ Differ 21:327–336

Blair C, Razza RP (2007) Relating effortful control, executive function, and false belief understanding to emerging math and literacy ability in kindergarten. Child Dev 78:647–663

Riggs NR, Jahromi LB, Razza RP, Dillworth-Bart JE, Mueller U (2006) Executive function and the promotion of social–emotional competence. J Appl Dev Psychol 27:300–309

Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Belsky D et al (2011) A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108:2693–2698

Burgess PW, Alderman N, Forbes C et al (2006) The case for the development and use of “ecologically valid” measures of executive function in experimental and clinical neuropsychology. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 12:194–209

Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA (2000) Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms & profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families, Burlington

Barkley RA (1997) Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychol Bull 121:65–94

Martinussen R, Hayden J, Hogg-Johnson S, Tannock R (2005) A meta-analysis of working memory impairments in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 44:377–384

Séguin JR (1999) Executive functions and physical aggression after controlling for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, general memory, and IQ. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 40:1197–1208

Willcutt EG, Doyle AE, Nigg JT, Faraone SV, Pennington BF (2005) Validity of the executive function theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. Biol Psychiatry 57:1336–1346

Sullivan JR, Riccio CA (2007) Diagnostic group differences in parent and teacher ratings on the BRIEF and Conners’ scales. J Atten Disord 11:398–406

Tan A, Delgaty L, Steward K, Bunner M (2018) Performance-based measures and behavioral ratings of executive function in diagnosing attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children. ADHD Attent Deficit Hyperact Disord 10:309–316

Pauli-Pott U, Becker K (2011) Neuropsychological basic deficits in preschoolers at risk for ADHD: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 31:626–637

Mahone EM, Hoffman J (2007) Behavior ratings of executive function among preschoolers with ADHD. Clin Neuropsychol 21:569–586

Skogan AH, Zeiner P, Egeland J, Rohrer-Baumgartner N, Urnes A-G, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Aase H (2014) Inhibition and working memory in young preschool children with symptoms of ADHD and/or oppositional-defiant disorder. Child Neuropsychol 20:607–624

Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL et al (2001) The relations of regulation and emotionality to children’s externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Dev 72:1112–1134

Ezpeleta L, Granero R (2015) Executive functions in preschoolers with ADHD, ODD, and comorbid ADHD-ODD: evidence from ecological and performance-based measures. J Neuropsychol 9:258–270

Bloemen AJP, Oldehinkel AJ, Laceulle OM, Ormel J, Rommelse NNJ, Hartman CA (2018) The association between executive functioning and psychopathology: general or specific? Psychol Med 48:1787–1794

Vilgis V, Silk TJ, Vance A (2015) Executive function and attention in children and adolescents with depressive disorders: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 24:365–384

Skogan AH, Zeiner P, Egeland J, Urnes A-G, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Aase H (2015) Parent ratings of executive function in young preschool children with symptoms of attention-deficit/-hyperactivity disorder. Behav Brain Funct 11:16

Kertz SJ, Belden AC, Tillman R, Luby J (2016) Cognitive control deficits in shifting and inhibition in preschool age children are associated with increased depression and anxiety over 7.5 years of development. J Abnorm Child Psychol 44:1185–1196

Nelson TD, Kidwell KM, Nelson JM, Tomaso CC, Hankey M, Espy KA (2018) Preschool executive control and internalizing symptoms in elementary school. J Abnorm Child Psychol 46:1509–1520

Bergman LR, Andersson H (2010) The person and the variable in developmental psychology. J Psychol 218:155–165

Bergman LR, Magnusson D (1997) A person-oriented approach in research on developmental psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol 9:291–319

Von Eye A, Bergman LR (2003) Research strategies in developmental psychopathology: dimensional identity and the person-oriented approach. Dev Psychopathol 15:553–580

Kavanaugh BC, Dupont-Frechette JA, Tellock PP, Maher ID, Haisley LD, Holler KA (2016) Neurocognitive phenotypes in severe childhood psychiatric disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis 204:770–777

Dajani DR, Llabre MM, Nebel MB, Mostofsky SH, Uddin LQ (2016) Heterogeneity of executive functions among comorbid neurodevelopmental disorders. Sci Rep 6:36566

Coskun M, Kaya I (2016) Prevalence and patterns of psychiatric disorders in preschool children referred to an outpatient psychiatry clinic. Anadolu Kliniği Tıp Bilimleri Dergisi 21:42–47

Wilens TE, Biederman J, Brown S, Monuteaux M, Prince J, Spencer TJ (2002) Patterns of psychopathology and dysfunction in clinically referred preschoolers. J Dev Behav Pediatr 23:S31–S36

Klenberg L, Tommo H, Jämsä S, Häyrinen T (2017) Pienten lasten keskittymiskysely PikkuKesky. Käsikirja [The attention and executive functions rating inventory ATTEX-P. Handbook]. Hogrefe Publishing Corp., Helsinki

Official Statistics of Finland (OSF): population structure [e-publication]. ISSN = 1797-5395. Helsinki: Statistics Finland [referred: 16.8.2019]. Access method: http://www.stat.fi/til/vaerak/index_en.html

Official Statistics of Finland (OSF): Educational structure of population [e-publication]. ISSN = 2242-2919. Helsinki: Statistics Finland [referred: 16.8.2019]. Access method: http://www.stat.fi/til/vkour/index_en.html

Ivanova MY, Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA et al (2010) Preschool psychopathology reported by parents in 23 societies: testing the Seven-Syndrome model of the child behavior checklist for ages 1.5–5. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 49:1215–1224

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Erlbaum, Hillsdale

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (1998–2017) Mplus User’s Guide, 8th edn. Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles

Celeux G, Soromenho G (1996) An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. J Classif 13:195–212

Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO (2007) Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct Equ Model Multidiscip J 14:535–569

Cataldo MG, Nobile M, Lorusso ML, Battaglia M, Molteni M (2005) Impulsivity in depressed children and adolescents: a comparison between behavioral and neuropsychological data. Psychiatry Res 136:123–133

Noordhof A, Krueger RF, Ormel J, Oldehinkel AJ, Hartman CA (2015) Integrating autism-related symptoms into the dimensional internalizing and externalizing model of psychopathology. The TRAILS study. J Abnorm Child Psychol 43:577–587

Klenberg L, Hokkanen L, Lahti-Nuuttila P, Närhi V (2017) Teacher ratings of executive function difficulties in finnish children with combined and predominantly inattentive symptoms of ADHD. Appl Neuropsychol Child 6:305–314

Gioia GA, Isquith PK, Kenworthy L, Barton RM (2002) Profiles of everyday executive function in acquired and developmental disorders. Child Neuropsychol 8:121–137

Leung RC, Zakzanis KK (2014) Brief report: cognitive flexibility in autism spectrum disorders: a quantitative review. J Autism Dev Disord 44:2628–2645

Rosenthal M, Wallace GL, Lawson R, Wills MC, Dixon E, Yerys BE, Kenworthy L (2013) Impairments in real-world executive function increase from childhood to adolescence in autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychology 27:13–18

Gardiner E, Hutchison SM, Müller U, Kerns KA, Iarocci G (2017) Assessment of executive function in young children with and without ASD using parent ratings and computerized tasks of executive function. Clin Neuropsychol 31:1283–1305

Sergeant JA, Geurts H, Oosterlaan J (2002) How specific is a deficit of executive functioning for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? Behav Brain Res 130:3–28

Toplak ME, West RF, Stanovich KE (2013) Practitioner review: do performance-based measures and ratings of executive function assess the same construct?: Performance-based and rating measures of EF. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 54:131–143

Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT (1983) Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychol Bull 101:213

Hinshaw SP, Han SS, Erhardt D, Huber A (1992) Internalizing and externalizing behavior problems in preschool children: correspondence among parent and teacher ratings and behavior observations. J Clin Child Psychol 21:143–150

Dekker MC, Ziermans TB, Spruijt AM, Swaab H (2017) Cognitive, Parent and teacher rating measures of executive functioning: shared and unique influences on school achievement. Front Psychol 8:48

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Jyväskylä (JYU). We are grateful to all the children and caregivers who participated in this study.

Funding

This study was supported by Grants from Helsinki University Central Hospital Research funds, a non-profit organization (TYH2013205 and TYH2016202) (Aronen and Huhdanpää).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the study was granted from the Helsinki University Central Hospital Ethical Committee for Paediatrics, Adolescent Medicine, and Psychiatry. All procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Teivaanmäki, S., Huhdanpää, H., Kiuru, N. et al. Heterogeneity of executive functions among preschool children with psychiatric symptoms. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 29, 1237–1249 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01437-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01437-y