Abstract

Purpose

Spinal solitary fibrous tumor/hemangiopericytoma (SFT/HPC), a rare mesenchymal tumor that arises from pericytes of Zimmerman, comprises only 0.08% of all primary bone tumors and 0.1% of primary malignant bone tumor and rarely occurs in the spine. We attempt to correlate the clinical factors and different treatment options with the recurrence rate and overall survival of SFT/HPC over time.

Methods

A retrospective study of 20 patients with spinal osseous SFT/HPCs who were surgically treated in our center between 2003 and 2015 was performed. Kaplan–Meier curves and log-rank tests were used to compare the survival probability or recurrence-free probability between groups, and P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Three surgical management strategies, including subtotal resection, piecemeal total resection, and total en bloc spondylectomy (TES) were applied. Postoperative radiotherapy was carried out in 14 cases. The mean follow-up period was 38.3 (median 35, range 7–93) months, and 6 patients passed away with the mean follow-up time of 47.7 (median 41, range 24–77) months. Relapse was detected in 9 patients (45%) with the mean time from surgery to recurrence being 36.6 (median 28, range 12–73) months. Our results indicate that grade III is an adverse prognostic factor for both recurrence and over survival (OS) for spinal osseous SFT/HPC, while total resection, especially TES, is a positive prognostic factor.

Conclusions

Spinal osseous SFT/HPC is a challenging clinical entity given its high local recurrence rate. Surgical management plays a crucial role in the whole treatment of spinal SFT/HPCs and total excision, especially TES, should be strived for whenever possible. Postoperative radiotherapy is recommended to lower the recurrent rate. This study also confirms that pathology grade III is an adverse prognostic factor for spinal osseous SFT/HPCs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) introduced the combined term solitary fibrous tumor/hemangiopericytoma (SFT/HPC) as SFT and HPS share common inversions at 12q13 leading to STAT6 nuclear expression [1]. SFT/HPC, a rare aggressive neoplasm of mesenchymal origin, comprises only 0.08% of all primary bone tumors and 0.1% of primary malignant bone tumors [2], and rarely affects the spine [3,4,5]. To date, only about 90 cases have been reported and most of them are intradural-extramedullary tumors [6, 7]. Spinal osseous SFT/HPC is particularly rare, and there are only case reports [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15] without case series.

Because of its rarity, there is limited information about the natural history and the management of the disease. Total en bloc resection was recommended for the treatment of extremities SFT/HPC [2]. However, spinal complex anatomy hinders total en bloc spondylectomy (TES) treatment which may lead to higher recurrence and lower overall survival. In this retrospective study, we tried to identify the clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of the spinal osseous SFT/HPC by analyzing the clinical data of 20 patients treated in our center between 2003 and 2015.

Patients and methods

20 patients who were surgically treated and documented in our center were included with 4 patients admitted for local recurrence. Relevant clinical, surgical and radiological data were collected by retrospective medical records review. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the hospital, and informed consent was obtained from the surviving patients or family members of those who had passed away.

The pre- and postoperative neurologic status was classified according to the Frankel score [16]. All patients received at least one surgery in our center through individualized approaches according to the Weinstein–Boriani–Biagini (WBB) system [17]. The screw-rod system was used to reconstruct stability of the spine for all patients. Two experienced neuro-pathologists confirmed the pathological diagnosis of SFT/HPC independently and the diagnoses were classified as grade III (anaplastic) or grade II in accordance with the criteria described by 2016 CNS WHO [1].

We aimed to identify prognostic factors for patients with spinal SFT/HPCs after surgery by focusing on recurrence and over survival (OS) after the initial surgery in our center. Relapse was defined as local tumor growth on the basis of the clinical manifestations and imaging findings (such as enhanced MRI or CT scans). Regular assessments were performed at 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery, every 6 months for the next 2 years, and then annually for life. Follow-up data were obtained from office visits and telephone interviews. The follow-up period was defined as the interval from the date of surgery to death, or until March 2016 for living patients.

Statistical method

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The univariate analyses of various clinical factors were performed to identify possible variables which could predict recurrence and OS. We avoided multivariate analyses as there were only 20 cases in this series. The patient factors were age, gender, and preoperative Frankel score. The tumor factors were location, number of involved segments and the WHO grade. The treatment factors were preoperative selective artery embolism (PAE), resection mode, intraoperative blood loss and adjuvant radiotherapy. The survival probability and recurrence-free probability were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier methods. Log-rank tests were used to compare the survival probability or recurrence-free probability between groups. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient features

The essential information of 20 cases is summarized in Table 1. Our series comprised 9 men and 11 women, with a mean age of 39.3 (median 47, range 10–57) years. Of these patients, 14 (70.0%) were in the fourth or fifth decades. Lesions were detected in the cervical (n = 6), thoracic (n = 8), lumbar spine (n = 5) and sacrum (n = 1). 9 out of 11 (81.8%) grade II SFT/HPCs involved the cervical–thoracic segments, while the thoracic–lumbar segments were more frequently infringed by grade III (7 out of 9, 77.8%). In addition, lesion involving one segment occurred in 10 patients, while the other 10 patients had 2 or 3 segments involvements. Localized pain in the spine was the most common complaint with a mean duration of 4.8 (mean 3.5, range 0.5–15) months. Additional symptoms included varying degrees of cord compression at diagnosis in 13 (65%) patients with the Frankel score ranging from C to D and one patient showed the palpable mass near the lesion (case 9).

The mean radiological follow-up time was 34.3 (median 27, range 6–93) months. While the mean clinical follow-up period was 38.3 (median 35, range 7–93) months, and 6 patients passed away with the mean follow-up time of 47.7 (median 41, range 24–77) months. Relapse was detected in 9 patients (45%) after the initial surgery in our center with the mean time from surgery to recurrence being 36.6 (median 28, range 12–73) months.

Treatment history

Four patients received prior treatment at other institutions. One of them (case 16) received total resection followed by conventional radiation therapy 14 years ago. Three cases (cases 4, 11 and 17) had already been subjected to incomplete tumor resections at other institutions and were admitted to our center because of recurrence.

Radiologic study

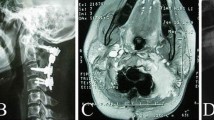

Lesion extension was described according to the WBB system, based on CT and MR images. The plain radiographic features were nonspecific and compression fracture was uncommon (25.0%, 5 out of 20) in our cases. On CT scan, 7 out of 11 (63.6%) grade II SFT/HPC lesions appeared as a well-defined, heterogeneous or homogeneous iso-dense mass with sclerotic bone responses, and showed moderate to marked enhancement following contrast administration (Fig. 1). By contrast, 6 out of 9 (66.7%) grade III SFT/HPCs lesions showed ill-circumscribed margins with paravertebral mass (Fig. 2). A heterogeneous enhancement after the administration of a contrast medium was observed in MRI images in all cases.

A 42-year-old man (case 9, WHO grade III). No compression fracture occurred preoperative in plain X-ray (a). Preoperative CT (b) and MRI (c, d) scan showed an osteolytic lesion in vertebraes and attachments of C5-6 which was close to the left vertebral artery. Intraoperative image (e) showed the posterior reconstruction and the left intact vertebral artery. Postoperative X-ray (f) showed sound reconstruction by an anterior cervical plate, a titanium mesh and posterior screw-rod system

A 35-year-old woman (case 20, WHO grade II). The plain X-ray showed slightly osteolytic change of the L2 (a). Preoperative MRI (b) and CT (c) scan showed a well-circumscribed osteolytic lesion in vertebrae and attachments of L2 (WBB: b–d layer, 2–7 section). Postoperative X-ray (d) showed sound reconstruction by a titanium mesh and posterior screw-rod system

Pathology

Pathological diagnosis of HPC was made by identifying typical features such as the branching ‘‘staghorn’’ vasculature, the widespread staining for reticulin and the absence of staining for epithelial membrane antigen. According to the 2016 WHO guidelines [1], tumors with anaplastic features were grade III, which is characterized by high mitotic activity (more than five mitoses per 10 high-power field) and grade II lesions usually indicate “SFT” or low-grade HPC. In our study, 9 (45%) patients were assessed as grade III, while 11 patients (55%) were classified as grade II. Immunohistochemistry showed the following: the positive rates of vimentin, CD34, CD31, CD99, bcl-2, CK, S100, NSE and EMA were 19/20 (95%), 17/18 (94.4%), 10/12 (83.3%), 7/12 (58.3%), 13/13 (100%), 1/9 (11.1%), 2/18 (11.1%), 1/7 (14.3%), 5/16 (31.3%), respectively (Fig. 3). For Ki-67 labeling index, although there was no statistical difference between two groups for relapse rate (P = 0.327) and OS (P = 0.576), it was relatively higher in anaplastic group. Mean Ki-67 labeling index was 18.1% with a range of 8–40% for grade III SFT/HPCs, while for grade II, the index was 5.5% with a range of 2–10%.

(×400) Hematoxylin–eosin-stained (HE) section: tumor cells were arranged in sheets and fascicles with intervening staghorn-shaped blood vessels. Immunohistochemical study showing CD 34 positive diffusely, CD 31 vessels positive, EMA focal positive, VEGF slight positive and Ki-67 15% positive (WHO grade II)

Prognosis and survival analysis

The survival analysis of clinical factors is shown in Table 2. Postoperative recurrence is not uncommon for osseous SFT/HPC [2, 3, 18, 19]. In our study, the overall relapse rate was 45%.

Surgery was performed in all cases; 5 patients underwent subtotal resection and 15 had total resection including 5 TES (Table 3). The results demonstrated significantly (P = 0.003) lower relapse in cases of total resection, especially TES, in comparison with those of subtotal resection. Mean recurrence-free survival in patients undergoing total resection surgery was 37.6 (range 11–93) months. Conversely, patients with a subtotal resection had a mean recurrence-free survival time of 21 (range 7–53) months. Also, the mortality trends for total and subtotal resections (Table 3) were statistically (P = 0.013) different and subtotal resection was observed to be related to higher incidences (60%) of mortality. The mean intraoperative blood loss was 1765 (median 1200, range 500–4500) ml. There was no significant difference in recurrence rate in patients with intraoperative blood loss [2000 ml and those B 2000 ml (P = 0.579)]. PAE was used in ten patients to reduce intraoperative blood loss, but no significant difference in recurrence rate or OS was observed (P = 0.48, 0.475) (Fig. 4a, b).

Postoperative relapse occurred in 66.7% (6/9) of grade III patients in this study. In comparison, only 27.3% (3/11) of grade II patients developed local recurrence. The median relapse-free survival was 36 months for grade II HPC and 23 months for grade III. In log-rank analysis, grade III tumors were associated with a higher recurrence rate (P = 0.001) and a decreased OS (P = 0.013) (Fig. 4c, d).

Postoperative radiotherapy was performed in 14 patients with the median dose of 45 Gy (range 40–55). There was no statistical difference between the two groups in relapse-free survival or OS (P = 0.571, 0.283). No significant differences were shown in other factors such as age, gender, preoperative Frankel score, location, treatment history, numbers of involved segment and intraoperative blood loss.

Complications

Pleural damage occurred in one patient (case 8) and pleurocentesis and drainage were conducted to alleviate the postoperative pleural effusion. For case 11, the left cervical nerve (C7) was invaded by the lesions and had to be sacrificed. Postoperative dysphonia occurred in one patient (case 4) and vanished gradually within 1 year without special intervention.

Discussion

SFT/HPC is a rare and potentially aggressive lesion and SFT/HPC of bone is even rarer, accounting for 0.1% of malignant primary bone tumors and 11% of malignant vascular bone tumors [11]. Because of the low incidence of spinal osseous SFT/HPC, the biological behavior and prognosis factors were poorly understood. In this study, we analyzed the clinical data of 20 patients with primary epidural SFT/HPCs and performed univariate statistical analysis to investigate the prognostic factors affecting postoperative recurrence and OS. The results indicated that WHO grade III and total resection, especially TES, were independent prognostic factors for both recurrence and OS.

In our series, the similar gender distribution was seen, which was against the idea that osseous SFT/HPC occurred with a slight predominance among males [1, 15, 19, 20]. In previous reports [6, 7], intraspinal HPCs commonly occurred in the cervical and thoracic segments of the spine and rarely in the lumbar and sacral segments. Our results are in accord with these reports that 14 out of 20 (70%) cases located at the cervical and thoracic spine, while thoracic–lumbar segments were more frequently infringed by grade III SFT/HPCs (7 out of 9, 77.8%). Solitary segment involvement was found in half of the cases and 65% of the cases endured neurologic disorders. Only one patient showed the palpable mass near the lesion (case 9), which was not same with other reports [2, 4] which stated that osseous spinal SFT/HPC was more likely to have paravertebral extension and less likely to involve the vertebral canal. Localized pain in the spine was the most common complaint, with 80% of cases enduring less than 6 months before admission.

The radiographic changes were nonspecific [2]. CT scan is superior to X-ray in evaluating bone destruction, and MRI is more accurate in detecting extraosseous extent of the tumor [11, 21]. MRI, especially with gadolinium enhancement, remains as an important choice for better definition of lesions and for evaluating relations with the thecal sac, spinal nerves and major vessels. In our series, the radiological differential diagnoses included giant cell tumors, malignant schwannoma, benign hemangioma (case 3), and other metastatic tumors. Osteolytic changes were common for spinal SFT/HPCs and soft tissue extension was more apparent for grade III lesions (66.7%).

Since the WHO classification of SFT/HPC in 2016 [1], there was no study examining the difference in outcomes between spinal osseous grade II and III SFT/HPC. McMaster et al. [22] studied soft tissue SFT/HPC and concluded that malignant variants (WHO grade III) had a higher risk of recurrence and metastases. Omprakash et al. [23] reported that for primary intracranial SFT/HPC, grade II tumours were associated with better survival than grade III using multivariate analysis (P = 0.044). Our study is the first to show that for the spinal osseous cases, grade III were associated with a higher recurrence rate (P = 0.001) and a decreased OS (P = 0.013) than grade II lesions, which may be due to the higher filtration feature of WHO III lesion [8, 10].

Surgery with the aim of preserving functionality, relieving pain, controlling local recurrence and promising a prolonged survival is the foundational treatment strategy for osseous SFT/HPCs in the spine [4, 5, 7]. Because SFT/HPCs, especially grade III, have the character of local infiltration, the local recurrence rate will be high if surgery is inadequate [4, 8, 10]. The surgical procedures applicable to the spinal column include the simplest subtotal resection, piecemeal total spondylectomy, and the most complex TES [17, 24,25,26]. In our retrospective review of these cases, it appeared that subtotal resection led to a high rate of tumor recurrence. For example, for three patients who were treated at other hospitals for a single vertebral lesion, MRI detected recurrence of the lesion in the original segment and even in the adjacent vertebrae and surrounding soft tissue several months later. In those cases, surgical resection and reconstruction of the spine were more difficult and TES was unfeasible. The univariant analysis in our study suggested that total resection could significantly decrease recurrence rate (P = 0.003) and prolong the OS (P = 0.023) of spinal SFT/HPCs.

Some researchers reported that piecemeal total resection with postoperative radiotherapy was sufficient for spinal grade II SFT/HPCs because of its slow and non-aggressive course [18, 27], but the majority of experts held the view that TES was the best treatment when it was possible [2, 5, 18, 25]. In our study, piecemeal total resection showed better prognosis than subtotal resection (P < 0.001), but the relapse rate was as high as 60% for grade III and 40% for grade II. The reason may be that piecemeal total spondylectomy is associated with a possibility of tumor cell contamination in the surgical field [17, 23,24,25,26]. As a result, due to the lower filtration feature and relatively clear lesion margin, it is of great significance to conduct the TES for the grade II SFT/HPCs when possible. In our cases, only 1 of 5 who had TES showed relapse 73 months after the initial surgery.

Concern about the high risk of recurrence was the most common reason for adjuvant radiation treatment [27, 28]. Radiotherapy and chemotherapy had been used as adjuvant therapies for spinal SFT/HPCs, especially for the recurred lesions 19. Guthrie et al. [29] also noted a relapse-free time improvement from 34 to 75 months for meningeal SFT/HPC. Meanwhile, radiotherapy alone may be helpful in the treatment of inoperable or small SFT/HPC lesions [30]. In our study, patients who underwent radiotherapy did not show statistical difference compared to others in relapse-free survival or OS (P = 0.571, 0.283). However, we still assume that radiotherapy should be regarded as a beneficial supplement after removal of the gross mass for spinal SFT/HPCs. Chemotherapy was ineffective in the treatment of spinal SFT/HPCs [19, 30]. In a study where 12 patients underwent chemotherapy as salvage treatment, only one patient responded to treatment by the shrinkage of the pulmonary metastases [19]. As a result, no patient in our study received postoperative chemotherapy.

Osseous SFT/HPC in the spine is a topic rarely reported and as far as we know, our series is the largest series to date. However, there are some limitations in this study. First, this is a retrospective study, being performed over 12 years, with all the limitations thereof. Surgical techniques, treatment of spinal cord injury and postoperative adjuvant therapies have been considerably more developed during the follow-up period. These developments may aid in safely accomplishing tumor removal and avoiding postoperative complications, therefore, exerting an effect on the surgical and clinical outcome of the surgery. Second, as there were only 20 cases in our series, we utilized log-rank tests and Kaplan–Meier analyses and avoided multivariate analyses. Third, the functions of radiotherapy and chemotherapy for spinal SFT/HPC were still unclear and may need future investigations.

Conclusion

Spinal osseous SFT/HPC is a challenging clinical entity given its high local recurrence rate. Surgical management plays a crucial role in the whole treatment of spinal SFT/HPCs and as subtotal excision easily leads to relapse, total excision, especially TES, should be strived for whenever possible. Postoperative radiotherapy is recommended to lower the recurrent rate. This study also confirms that pathology grade III is an adverse prognostic factor for spinal osseous SFT/HPCs.

References

Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G et al (2016) The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol 131:803–820

Tang JS, Gold RH, Mirra JM et al (1988) Hemangiopericytoma of bone. Cancer 62(4):848–859

Espat NJ, Lewis JJ, Leung D et al (2002) Conventional hemangiopericytoma: modern analysis of outcome. Cancer 95(8):1746–1751

Zhang P, Hu J, Zhou D (2014) Hemangiopericytoma of the cervicothoracic spine: a case report and literature review. Turk Neurosurg 24(6):948–953

Ren K, Zhou X, Wu S et al (2014) Primary osseous hemangiopericytoma in the thoracic spine. Clin Neuropathol 33(5):364–370

Liu HG, Yang AC, Chen N et al. (2013) Hemangiopericytomas in the spine: clinical features, classification, treatment, and long-term follow-up in 26 patients. Neurosurgery 72(1):16–24

Das A, Kumar P, Suri SV et al (2015) Spinal hemangiopericytoma: an institutional experience and review of literature. Eur Spine J 24(Suppl 4):S606–S613

Liu J, Cao L, Liu L et al (2014) Primary epidural hemangiopericytoma in the sacrum: a rare case and literature review. Tumour Biol 35(11):11655–11658

Lin YJ, Tu YK, Lin SM et al. (1996) Primary hemangiopericytoma in the axis bone: case report and review of literature. Neurosurgery 39(2):397–399

Mohammadianpanah M, Torabinejad S, Bagheri MH et al (2004) Primary epidural malignant hemangiopericytoma of thoracic spinal column causing cord compression: case report. Sao Paulo Med J 122(5):220–222

Lian YW, Yao MS, Hsieh SC et al (2004) MRI of hemangiopericytoma in the sacrum. Skelet Radiol 33(8):485–487

Ramdasi RV, Nadkarni TD, Goel NA (2014) Hemangiopericytoma of the cervical spine. J Craniovertebr Junction Spine 5(2):95–98

Kumar R, Vaid VK, Kumar V et al (2007) Hemangiopericytoma of thoracic spine: a rare bony tumor. Childs Nerv Syst 23(10):1215–1219

Ijiri K, Yuasa S, Yone K et al (2002) Primary epidural hemangiopericytoma in the lumbar spine: a case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 27(7):E189–E192

Ghose A, Guha G, Kundu R et al (2017) CNS hemangiopericytoma a systematic review of 523 patients. Am J Clin Oncol 40(3):223–227. https://doi.org/10.1097/COC.0000000000000146

Frankel HL, Hancock DO, Hyslop G et al (1969) The value of postural reduction in the initial management of closed injuries of the spine with paraplegia and tetraplegia: I. Paraplegia 7(3):179–192

Boriani S, Weinstein JN, Biagini R (1997) Primary bone tumors of the spine: terminology and surgical staging. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 22(9):1036–1044

Chen H, Zeng X-W, Jin-Song W et al (2012) Solitary fibrous tumor of the central nervous system: a clinicopathologic study of 24 cases. Acta Neurochir. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-011-1160-9

Ecker RD, Richard Marsh W, Pollock BE et al (2003) Hemangiopericytoma in the central nervous system: treatment, pathological features, and long-term follow up in 38 patients. J Neurosurg 98(1182–1187):2003

Chmielecki J, Crago AM, Rosenberg M et al (2013) Whole-exome sequencing identifies a recurrent NAB2-STAT6 fusion in solitary fibrous tumors. Nat Genet 45:131–132. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2522

Yi X, Xiao D, He Y et al (2017) Spinal solitary fibrous tumor/hemangiopericytoma: a clinicopathologic and radiologic analysis of eleven cases. World Neurosurg. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2017.05.016

McMaster MJ, Soule EH, Ivins JC (1975) Hemangiopericytoma. A clinicopathologic study and long-term followup of 60 patients. Cancer 36(6):2232–2244

Damodaran O, Robbins P, Knuckey N et al (2014) Primary intracranial hemangiopericytoma: comparison of survival outcomes and metastatic potential in WHO grade II and III variants. J Clin Neurosci 21(8):1310–1314

Tomita K, Kawahara N, Murakami H et al (2006) Total en bloc spondylectomy for spinal tumors: improvement of the technique and its associated basic background. J Orthop Sci 11(1):3–12

Onoki T, Kanno H, Aizawa T et al (2017) Recurrent primary osseous hemangiopericytoma in the thoracic spine: a case report and literature review. Eur Spine. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-017-5322-1

Jia Q, Yin H, Yang J et al (2017) Treatment and outcome of metastatic paraganglioma of the spine. Eur Spine J. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-017-5140-5

Dufour H, Metellus P, Fuentes S et al (2001) Meningeal hemangiopericytoma: a retrospective study of 21 patients with special review of postoperative external radiotherapy. Neurosurgery 48:756–763

Benzil DL, Saboori M, Mogilner AY et al (2004) Safety and efficacy of stereotactic radiosurgery for tumors of the spine. J Neurosurg 101(suppl 3):413–418

Guthrie BL, Ebersold MJ, Scheithauer BW et al (1989) Meningeal hemangiopericytoma: histopathological features, treatment, and long-term follow-up of 44 cases. Neurosurgery 25(4):514–522

Galanis E, Buckner JC, Scheithauer BW et al (1998) Management of recurrent meningeal hemangiopericytoma. Cancer 82(10):1915–1920

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Source of funding

This work was supported in part by the China Scholarship Council (Grant no. 201603170230).

Conflict of interest

No benefits in any form have been or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this manuscript. No conflict of interest exists in the submission of this manuscript for all authors, and manuscript is approved by all authors for publication.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Jia, Q., Zhou, Z., Zhang, D. et al. Surgical management of spinal solitary fibrous tumor/hemangiopericytoma: a case series of 20 patients. Eur Spine J 27, 891–901 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-017-5376-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-017-5376-0