Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study focuses on the changes of the syrinx volume after posterior reduction and fixation of the basilar invagination (BI) and atlantoaxial dislocation (AAD) with syringomyelia.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed the clinical outcome and syrinx volume changes in 71 patients with BI, AAD and syringomyelia treated with the posterior reduction and fixation technique.

Results

Clinical improvement was observed in 64 (90.1 %) patients postoperatively; 5 (7.0 %) were stable and 2 (2.8 %) were clinically aggravated. The postoperative Atlantodental interval became normal in 61 patients (86.0 %); showed reduction that was greater than 50 % but not complete in 5 patients (7.0 %); and reduction which was less than 50 % in 5 patients (7.0 %). The size of the syrinx was reduced postoperatively in 66 patients (93.0 %) while no change in the remaining 5 patients (7.0 %).

Conclusions

Posterior reduction and fixation of the AAD and BI can effectively enlarge the foramen magnum, improve the cerebrospinal fluid circulation and consequently reduce the volume of the syrinx.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Basilar invagination (BI) is a congenital malformation of craniovertebral junction (CVJ), which is divided into two types based on whether it is associated with atlantoaxial dislocation (AAD) [1–3]. Syringomyelia is very common in the type of BI with AAD [3–6]. Traditionally, in patients affected by BI and AAD, transoral odontoidectomy could effectively decompress the foramen magnum (FM) and improve the clinical symptoms [5, 6]. In recent years, the posterior reduction and fixation technique has become the preferred treatment option for BI and AAD with favorable restoration of the AAD being reported [1, 2, 4, 7, 8]. However, there was a paucity of reports focusing on the clinical and radiological outcomes of the syringomyelia after the treatment. In this study, the clinical data of patients with BI/AAD and syringomyelia that underwent direct posterior reduction and fixation were retrospectively analyzed; the possible influencing factors of the syrinx volume were discussed.

Methods

Patient population

From September 2009 to October 2013, 175 patients with BI and AAD underwent treatment at our hospital. Among them, 86 patients had concomitant syringomyelia. In this study, long term magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and follow-up was required for evaluating the changes in the syrinx. However, 15 of 86 patients did not match with the inclusion criteria due to a lack of long term MRI or loss of follow-up. Seventy-one patients were successfully followed up for 6–43 months with an average of 22.7 months. Overall, 67 (94 %) patients were followed up for more than 12 months. The 71 patients included 31 males and 40 females ranging from 15 to 74 years old, with an average of 35.8 years of age. With the exception of four children between 15 and 17 years of age, all other patients in this series were adults. Clinical symptoms of the patients are shown in Table 1. The three most common symptoms were limbs weakness (85.9 %), limbs paresthesia (84.5 %) and head and neck pain (70.4 %). Neurological functions were evaluated by the 17-point scoring system of the Japanese Orthopedic Association (JOA).

Among the 71 patients, 59 (83.1 %) had Chiari I malformation (CM-I), 68 (95.8 %) had assimilation of atlas and 29 (40.8 %) had Klippel–Feil syndrome (KFS) (Fig. 1).

Radiologic examination and measurement

Preoperative X-ray, MRI and computed tomographic (CT) scans were performed in all patients. Syrinx size was measured with MRI and the maximum diameter in sagittal and axial images was recorded in millimeters with accuracy to 0.1 mm (Fig. 2). CT reconstruction was used to evaluate the bony abnormality of the FM (Fig. 3). Two senior spine surgeons did the radiologic assessments separately in a blind fashion. The value was measured on three separate occasions by both surgeons in 3-week intervals and then averaged.

Due to bony decompression of the FM, it was difficult to measure the Chamberlain line and McRae line directly after surgery. Consequently we measured the Wackenheim line only. The criterion for BI was that the tip of the odontoid process should be at least above the Wackenheim line [9]. The criterion for AAD was having an Atlantodental interval (ADI) greater than 3 mm among adults (>18 years old), whereas in younger individuals, a distance greater than 5 mm was considered abnormal [10]. Clivus axial angle (CAA) was the angle formed by Wackenheim’s line and a line constructed along the posterior margin of the dens and axis body. The angle normally ranges between 150° in flexion and 180° in extension [9].

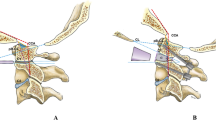

Surgical procedure

All 71 patients underwent posterior reduction and fixation procedure. This procedure has been previously described [1]. Reduction of the AAD was achieved by longitudinal distraction between the C2 pedicle and occipital (Oc) screws, which dragged the odontoid process downward and anteriorly. A small part of the posterior margin of FM (or the fused posterior arch of atlas) was removed followed by the occipitocervical fusion. After 2012, the distraction technique was modified; the odontoid process was pushed forward at first by C2 pedicle screw with cantilever technology before the distraction maneuver between the Oc and C2 screws.

Follow-up

X-ray and CT scans were performed after 1 week, 3 months, and from 6 months to 1 year after surgery. Postoperative MR imaging studies were obtained regularly on a 1 week and 3 months basis until evidence for syrinx reduction was found. This continued for a maximum of 18 months for cases not showing syrinx reduction. The fusion was confirmed using X-ray and CT scans.

The postoperative symptoms were classified as being improved (symptoms improved with or without other symptoms remaining), stabilized (the same symptoms as preoperative without progression), or aggravated (symptoms worsen).

The postoperative syrinx was reported to be either reduced (syrinx decreased in size ≥20 %) or unchanged (syrinx decreased in size <20 % or remained the same size). Reduction was reported to be satisfied when ADI became normal or greater than 50 %, and unsatisfied when reduction was less than 50 %.

Statistical methods

SPSS for Windows (SPSS software, version 17.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois) was used for the analysis. Wilcoxon signed ranks test was performed for pre- and postoperative JOA scores, syrinx size, Wackenheim line, CAA and ADI. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Surgery

The occiput-C2 fixation was performed in 60 patients, the fixation was extended to the C3 lateral mass in six patients, and the C1–C2 fixation was performed in the remaining five patients. Additional transoral surgeries were performed in two patients because of unsolved ventral compressions and no clinical improvements. Symptom improvements were observed in both patients postoperatively. All the surgeries were uneventful. The duration of the operation ranged from 90 to 180 min with blood loss ranging from 50 to 200 ml. Two patients had difficulty in tracheal intubation during anesthesia and extubated 2 days after surgery. There were no instrumentation failures.

Clinical results

Clinical improvements were observed in 64 (90.1 %) patients postoperatively; 5 (7.0 %) were stable and 2 (2.8 %) were clinically aggravated. The median pre- and postoperative JOA score was 12.8 and 14.5, respectively (P < 0.01).

There were no injuries of the vertebral artery or infection complications. Twelve (16.9 %) patients experienced dysphagia but made full recoveries within 3 days to 6 months. One patient had dyspnea and underwent tracheotomy; normal respiratory function was restored within 5 days. Muscle strength was decreased in one patient but recovered in 2 weeks’ time.

Radiologic follow-up

CT/MRI performed postoperatively indicated that 66 (93 %) satisfied reductions were achieved and 5 (7.0 %) unsatisfied reductions remained (reduction was less than 50 %). For the satisfied reductions, ADI became normal in 61 (86.0 %) patients and reduction was greater than 50 % but not complete in 5 (7.0 %) patients. The pre- and postoperative ADI, distance between odontoid apex and Wackenheim line and CAA are shown in Table 2.

Changes of syrinx

The size of the syrinx was reduced postoperatively in 66 patients (93.0 %) while no change in the remaining 5 patients (7.0 %). Among the 66 patients who experienced a reduction in syrinx, in 9 cases, the syrinx completely disappeared. Throughout the study, no increase in syrinx was found. The median pre- and postoperative size of syrinx was 6.9 and 3.0 mm, respectively (P < 0.01) (Table 2). Figure 4 shows a case with satisfied AAD restoration. It is evident that the size of syrinx was reduced postoperatively.

A 31 years old female patient with a history of cervico-occipital pain and bilateral arm numbness. a Preoperative CT scan showing BI and AAD. b Preoperative MRI showing BI and AAD with syringomyelia. c Postoperative X-ray showing the effective fixation. d Postoperative CT scan showing the successful restoration of dislocation. e Postoperative MRI showing disappearance of the syrinx

In the five patients with no image change of the syrinx, four had unsatisfied reduction of the BI/AAD (Fig. 5), one had local kyphotic change and severe tonsillar herniation. The pre- and postoperative mean distance between the odontoid apex to the Wackenheim line was 4.6 and 3.2 mm; the mean pre- and postoperative ADI was 4.5 and 3.44 mm; the mean pre- and postoperative CAA was 120.0° and 118.9°, respectively.

Discussion

Mechanism of BI/AAD combining with syringomyelia

Although many theories have been proposed [11–15], the pathogenesis of syringomyelia is still unclear. It is generally accepted that syringomyelia is caused by disturbances of normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow circulation [7, 11–13, 16, 17]. Several studies have revealed that BI/AAD are associated with syringomyelia [4–7, 12], but there is a paucity of reports focusing on mechanism of BI/AAD combined with syringomyelia. This study found that there are three factors which may be the reasons for syringomyelia in patients with BI/AAD: (1) ventral compression by dislocated odontoid process. (2) Dorsal compression by Chiari I malformation. (3) Concomitant Klippel–Feil syndrome and occipitalization of atlas. Concrete analysis is as follows.

In Menezes’s study [6], 84 patients who had CM-I with CVJ abnormalities and syringomyelia underwent ventral decompression. The ventral decompression procedure was followed a week later by the dorsal decompression and fusion. During this time, interval postoperative MR imaging was performed and showed early improvement in the syrinx. A ventral decompression of the CVJ had been shown to allow for regression of the syrinx. In this series, evaluation of the radiological findings of 71 patients with BI/AAD, the dislocated odontoid process directly compressed the brainstem which decreased the dimension of the FM and obstructed CSF circulation. We speculate that ventral compression of the spinal cord caused by dislocated odontoid process is the primary reason of syringomyelia in patients with BI/AAD. Among 71 cases, 66 (93.0 %) cases experienced satisfied restoration of AAD/BI, and 65/66 (98.5 %) cases had syrinx shrinkage. It suggested that the relief of ventral compression was the main reason of regression of syrinx.

The pathogenesis of Chiari malformation (CM) with or without associated BI and/or syringomyelia is very complex. One of the current concepts is that there is a reduction in posterior fossa volume which obstructs the free communication of CSF flow from the cranial to the spinal subarachnoid space [5, 6, 18]. Posterior fossa decompression with or without duraplasty as treatment for symptomatic CM-I with syringomyelia has shown satisfactory results except in the presence of ventral bone abnormalities [12, 13, 16]. In Klekamp’s study [19], craniospinal stabilizations with the foramen magnum decompressions were performed in 31 patients with BI and CM-I and ventral compression, nine patients underwent transoral decompressions, and a favorable clinical result was achieved. Their studies indicated that ventral and dorsal compressions were commonly associated in patients with BI and CM-I, the ventral decompression and stabilization were very important. Recently, Goel [20] pointed out that the pathogenesis of CM with or without associated basilar invagination and/or syringomyelia is primarily related to atlantoaxial instability. His theory needed more prospective studies and research to be proved. Previous literatures show that Syringomyelia occurs in conjunction with CM in 50–70 % of patients [12, 21]. The rate of CM combining with BI/AAD/syringomyelia is still unclear. In this series, 59 (83.1 %) cases with BI/AAD/syringomyelia had concomitant CM-I. We speculate the dislocated odontoid shifts posteriorly, which compresses the CVJ and decreases the dimension of the FM. The concomitant hindbrain herniation makes the overcrowded FM worse and interrupts the CSF circulation.

Congenital fusion of C2 and C3 is most commonly seen in KFS [22]. Atlas occipitalization and congenital C2–3 fusion often lead to AAD and BI, eventually resulting in hypermobility or symptomatic stenosis of the CVJ [22]. These patients often have cervical myelopathy or concomitant anomalies such as BI, CM and syringomyelia [7, 23]. Patients with AAD and KFS had a significantly higher incidence of assimilated posterior arch of atlas compared to the patients with AAD as there was an increase in the Ishihara curvature index [24]. In our series, 68 (95.8 %) cases were combined with assimilation of atlas and 29 (40.8 %) cases were combined with KFS. The patients with assimilation of atlas and KFS frequently had cervical lordosis leading to odontoid process and greater inclination towards the spinal cord, and the normal CSF circulations were obstructed.

Treatment of BI/AAD with syringomyelia

Various surgical treatments of BI/AAD have been reported [1, 2, 4–6]. Preoperative cervical traction had been introduced in patients with BI/AAD to assess neurologic status and reducibility [4]. Several reports have detailed successful application of transoral approaches for BI/AAD [5, 6]. However, there continues to be several controversies regarding the optimal indications and approaches for anterior decompression [25]. In recent years, posterior approaches have become the primary methods for the treatment of BI/AAD [1, 2, 7, 8]. The direct posterior distraction technique seems to be an effective method.

In our series, a direct posterior reduction and fixation approach was used for all patients. Four pediatric patients between 15 and 17 years old received the same surgical treatment as adults. Pre- and intraoperative cervical tractions were never used. An AAD that is “irreducible” under cervical traction can become reducible by a direct intraoperative distraction technique. Only two patients had further transoral decompressions because of unsolved ventral compressions and no clinically improvements. The technique decompresses the spinal cord and medulla oblongata and expands the volume of FM, which alleviates the obstruction of CSF circulation and shrinks the syrinx. In this series, the direct posterior distraction technique showed a satisfactory result.

As a treatment for symptomatic CM with syringomyelia, posterior fossa decompression (PFD) has shown satisfactory results [12, 13, 16], but PFD for the treatment of CM with BI is controversial [7, 20, 26]. Some studies suggested that the surgical treatment of CM with BI and syringomyelia should be directed toward atlantoaxial stabilization and PFD is not necessary [7, 20]. Klekamp suggested that posterior fusion should be performed along with the foramen magnum decompression in the patients of CM with BI, regardless of pre- or intraoperative signs of instability [19]. A significant controversy also exists concerning whether the posterior decompression approach should be intradural or extradural [12, 13, 16, 19, 27]. In our series, all patients underwent resection of a small part of the posterior margin of FM. We consider that reduction and fusion is necessary, and PFD is a supplement of the expansion in posterior fossa volume. When the reduction is unsatisfied or tonsillar herniation is severe, PFD will play a partial role. Duroplasty was not used in our series; a good clinical efficacy was achieved and the complications correlated with duroplasty were avoided.

No change of the syrinx

Robert [14] performed a retrospective study of patients who developed worsening syringomyelia after Chiari decompression was performed. Each case in the study had a blockage of CSF pathways at the FM and most cases were found to have intradural scarring or an arachnoid web. Reports of worsening syringomyelia in the patients with BI/AAD after surgery were absent. In our series, postoperative follow-up in 71 cases with syringomyelia showed that 5 cases had no image changes of the syrinx. All of the five patients did not improve clinically. This phenomenon signified that the blockage of CSF flow at the CVJ was still unresolved after the surgery. The possible reason of why there was no change in syrinx is summarized as follows.

The primary reason is due to an unsatisfied reduction of the dislocated odontoid process. Under such circumstances, although the screw fixation and fusion improve stability of CVJ, the dislocated odontoid process still directly compressed the brainstem and obstructed CSF circulation (Fig. 5). In the five cases with unsatisfied reduction of the BI/AAD, only 1 (20 %) syrinx shrank.

Another reason is severe tonsillar herniation. Usually, if AAD restoration is satisfied, the concomitant syringomyelia will regress. However, when ventral compression is persistent, the unchanged severe tonsillar herniation will aggravate obstruction of CSF circulation. In this series, a patient with no image change of the syrinx had severe tonsillar herniation. The tonsillar tonsil herniated downward to C2 vertebral body level. After the surgery, ventral compression was not resolved completely and the herniated tonsillar aggravated the crowding of FM. Under such circumstances, the two-stage ventral decompression and/or tonsillectomy with duraplasty may be required.

Local excessive kyphosis is the third reason. The CCA can be used to quantify the amount of BI; ventral spinal cord compression may occur with angles less than 150° [9]. In the patients with BI and AAD, superior migration of the odontoid and/or the horizontal clivus can lead to direct compression of the brainstem and upper cervical spinal cord. These changes place the cervicomedullary junction in excessive kyphosis and decrease the CCA [9, 28]. In the five cases which had no image change of the syrinx of this series, the pre- and postoperative CAA was 120.0° and 118.9°. Although it was not statistically significant, it implied more severe local kyphosis after the surgery. In the case of a patient with severe local kyphosis, the pre- and postoperative CAA was measured to be 98° and 95.3°.

Although the patient’s postoperative odontoid apex was below Wackenheim line, anterior compression by local kyphosis was unresolved. The postoperative MR image revealed no syrinx change.

The pathology of syringomyelia combined with CVJ anomalies is only partially understood and its treatment is still a matter of debate; especially involving CM-I. This study will help with the recognition and awareness of this complicated pathology. The results suggested that the cranial vertebral realignment and internal fixation is the more appropriate technique in effectively managing this subgroup of patients. However, several limitations of this study still exist. Though 86 patients were matched with the inclusion criteria, only 71 could be documented in this series. The shortest follow-up period was 6 months which may not be long enough for this complex disease. After 2012, the distraction technique was modified. Thus, the effect of surgery had a chance to be affected by the use of different surgical methods.

Conclusions

The possible reason for patients affected by BI and AAD with concomitant syringomyelia is dislocation of the odontoid process which decreases the dimensions of the FM and obstructs CSF circulation. Coexisting tonsillar herniation and other types of malformations can aggravate the obstruction of CSF circulation. Posterior reduction and fixation technique combined with resection of posterior margin of the FM for this group of patients can effectively decompress the FM. Consequently this leads to shrinkage of the syrinx. Inadequate decompression of the FM, such as unsatisfied restoration of AAD, severe tonsillar herniation and local kyphosis, may lead to continuous clinical symptoms and radiological syrinx after surgery.

References

Feng-ZengJian Zan Chen, Karsten H, Samii M, Ling F et al (2010) Direct posterior reduction and fixation for the treatment of basilar invagination with atlantoaxial dislocation. Neurosurgery 66(4):678–687

Goel A (2004) Treatment of basilar invagination by atlantoaxial joint distraction and direct lateral mass fixation. J Neurosurg Spine 1(3):281–286

Nishikawa M, Ohata K, Baba M, Terakawa Y, Hara M (2004) Chiari I malformation associated with ventral compression and instability: one-stage posterior decompression and fusion with a new instrumentation technique. Neurosurgery 54(6):1430–1435

Goel A, Bhatjiwale M, Desai K (1998) Basilar invagination: a study based on 190 surgically treated patients. J Neurosurg 88(6):962–968

Fenoy AJ, Menezes AH, Fenoy KA (2008) Craniocervical junction fusions in patients with hindbrain herniation and syringohydromyelia. J Neurosurg Spine 9:1–9

Menezes AH (2012) Craniovertebral junction abnormalities with hindbrain herniation and syringomyelia: regression of syringomyelia after removal of ventral craniovertebral junction compression. J Neurosurg 116:301–309

Wang SL, Wang C, Yan M, Zhou HT, Jiang L (2010) Syringomyelia with irreducible atlantoaxial dislocation, basilar invagination and Chiari I malformation. Eur Spine J 19:361–366

Chandra PS, Kumar A, Chauhan A et al (2013) Distraction, compression, and extension reduction of basilar invagination and atlantoaxial dislocation: a novel pilot technique. Neurosurgery 72(6):1040–1053

Smoker WR, Khanna G (2008) Imaging the craniocervical junction. Childs Nerv Syst 24:1123–1145

Salunke P, Sharma M, Sodhi HBS, Mukherjee KK, Khandelwal NK (2011) Congenital atlantoaxial dislocation: a dynamic process and role of facets in irreducibility. J Neurosurg Spine 15:678–685

Ikenouchi J, Uwabe C, Nakatsu T, Hirose M, Shiota K (2002) Embryonic hydromyelia: cystic dilatation of the lumbosacral neural tube inhuman embryos. Acta Neuropathol 103(3):248–254

Nasser M (2012) Long-term outcome of surgical management of adult Chiari I malformation. Neurosurg Rev 35(4):537–547

Aghakhani N, Parker F, David P, Morar S, Lacroix C, BenoudibF Tadie M (2009) Long-term follow-up of Chiari-related syringomyelia in adults: analysis of 157 surgically treated cases. Neurosurgery 64(2):308–315

Naftel RP, Tubbs RS, Menendez JY (2013) Worsening or development of syringomyelia following Chiari I decompression. J Neurosurg Pediatr 12:351–356

Oldfield EH, Muraszko K, Shawker TH, Patronas NJ (1994) Pathophysiology of syringomyelia associated with Chiari I malformation of the cerebellar tonsils. Implications for diagnosis and treatment. J Neurosurg 80:3–15

Alfieri A, Pinna G (2012) Long-term results after posterior fossa decompression in syringomyelia with adult Chiari type I malformation. J Neurosurg Spine 17:381–387

Talacchi A, Meneghelli P, Borghesi I, Locatelli F (2016) Surgical management of syringomyelia unrelated to Chiari malformation or spinal cord injury. Eur Spine J 25(6):1836–1846

Williams B (1970) The distending force in the production of communicating syringomyelia. Lancet 2:41–42

Klekamp J (2015) Chiari I malformation with and without basilar invagination: a comparative study. Neurosurg Focus 38(4):1–13

Goel A (2015) Is atlantoaxial instability the cause of Chiari malformation? Outcome analysis of 65 patients treated by atlantoaxial fixation. J Neurosurg Spine 22:116–127

Batzdorf U (1988) Chiari I malformation with syringomyelia. Evaluation of surgical therapy by magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosurg 68:726–730

Shen FH, Samartzis D, Herman J, Lubicky JP (2006) Radiographic assessment of segmental motion at the atlantoaxial junction in the Klippel–Feil patient. Spine 31(2):171–177

Gholve PA, Hosalkar HS, Ricchetti ET, Pollock AN, Dormans JP, Drummond DS (2007) Occipitalization of the atlas in children. Morphologic classification, associations, and clinical relevance. J Bone Joint Surg Am 89(3):571–578

Sardhara J, Behari S, Jaiswal A et al (2013) Syndromic versus nonsyndromic atlantoaxial dislocation: do clinico-radiological differences have a bearing on management? Acta Neurochir 155:1157–1167

Kim LJ, Rekate HL, Klopfenstein JD, Sonntag VKH (2004) Treatment of basilar invagination associated with Chiari I malformations in the pediatric population: cervical reduction and posterior occipitocervical fusion. J Neurosurg 101(2):189–195

Menezes AH (2008) Craniovertebral junction database analysis: incidence, classification, presentation, and treatment algorithms. Childs Nerv Syst 24:1101–1108

Caldarelli M, Novegno F, Vassimi L, Romani R, Tamburrini G, Di RC (2007) The role of limited posterior fossa craniectomy in the surgical treatment of Chiari malformation type I: experience with a pediatric series. J Neurosurg 106(3):187–195

Wang SL, Wang C, Passias PG et al (2009) Interobserver and intraobserver reliability of the cervicomedullary angle in a normal adult population. Eur Spine J 18(9):1349–1354

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81271519) And National High Tech Research and development program of China (863 Program) (Grant No. 2013AA013803). The authors would like to acknowledge Jennifer Ai, Weisheng Zhang and Defa Chu for their help to the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Wang, X., Jian, F. et al. The changes of syrinx volume after posterior reduction and fixation of basilar invagination and atlantoaxial dislocation with syringomyelia. Eur Spine J 26, 1019–1027 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-016-4740-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-016-4740-9