Abstract

Background

Patients with newly diagnosed lung cancer who have not yet begun treatment may already be experiencing major symptoms produced by their disease. Understanding the symptomatic effects of cancer treatment requires knowledge of pretreatment symptoms (both severity and interference with daily activities). We assessed pretreatment symptom severity, interference, and quality of life (QOL) in treatment-naïve patients with lung cancer and report factors that correlated with symptom severity.

Methods

This was a retrospective analysis of data collected at initial intake. Symptoms/interference were rated on the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI) between 30 days prediagnosis and 45 days postdiagnosis. We examined symptom severity by disease stage and differences in severity by histology. Linear regression analyses identified significant predictors of severe pain and dyspnea.

Results

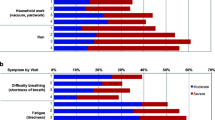

Of 460 eligible patients, 256 (62%) had adenocarcinoma, 30 (7%) had small cell carcinoma, and 100 (24%) had squamous cell carcinoma; > 30% reported moderate-to-severe (rated ≥ 5, 0–10 scale) pretreatment symptoms. The most-severe were fatigue, disturbed sleep, distress, pain, dyspnea, sadness, and drowsiness. Symptoms affected work, enjoyment of life, and general activity (interference) and physical well-being (QOL) the most. Patients with advanced disease (n = 289, 63%) had more-severe symptoms. Cancer stage was associated with pain severity; both histology and cancer stage were associated with severe dyspnea.

Conclusion

One third of lung cancer patients were symptomatic at initial presentation. Quantification of pretreatment symptom burden can inform patient-specific palliative therapy and differentiate disease-related symptoms from treatment-related toxicities. Poorly controlled symptoms could negatively affect treatment adherence and therapeutic outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hanna EY, Mendoza TR, Rosenthal DI, Gunn GB, Sehra P, Yucel E, Cleeland CS (2015) The symptom burden of treatment-naive patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer 121(5):766–773. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29097

Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Chou C, Harle MT, Morrissey M, Engstrom MC (2000) Assessing symptom distress in cancer patients: the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory. Cancer 89(7):1634–1646. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(20001001)89:7<1634::AID-CNCR29>3.0.CO;2-V

Reeve BB, Mitchell SA, Dueck AC, Basch E, Cella D, Reilly CM, Minasian LM, Denicoff AM, O’Mara AM, Fisch MJ, Chauhan C, Aaronson NK, Coens C, Bruner DW (2014) Recommended patient-reported core set of symptoms to measure in adult cancer treatment trials. J Natl Cancer Inst 106(7):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju129

Rosenthal DI, Mendoza TR, Chambers MS, Asper JA, Gning I, Kies MS, Weber RS, Lewin JS, Garden AS, Ang KK, Wang XS, Cleeland CS (2007) Measuring head and neck cancer symptom burden: the development and validation of the M. D. Anderson symptom inventory, head and neck module. Head Neck 29(10):923–931. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.20602

Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Lu C, Palos GR, Liao Z, Mobley GM, Kapoor S, Cleeland CS (2011) Measuring the symptom burden of lung cancer: the validity and utility of the lung cancer module of the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory. Oncologist 16(2):217–227. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0193

Armstrong TS, Mendoza T, Gning I, Coco C, Cohen MZ, Eriksen L, Hsu MA, Gilbert MR, Cleeland C (2006) Validation of the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory Brain Tumor Module (MDASI-BT). J Neuro-Oncol 80(1):27–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-006-9135-z

Wang XS, Williams LA, Eng C, Mendoza TR, Shah NA, Kirkendoll KJ, Shah PK, Trask PC, Palos GR, Cleeland CS (2010) Validation and application of a module of the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory for measuring multiple symptoms in patients with gastrointestinal cancer (the MDASI-GI). Cancer 116(8):2053–2063. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24920

Annakkaya AN, Arbak P, Balbay O, Bilgin C, Erbas M, Bulut I (2007) Effect of symptom-to-treatment interval on prognosis in lung cancer. Tumori 93(1):61–67. https://doi.org/10.1700/264.3004

Hopwood P, Stephens RJ (1995) Symptoms at presentation for treatment in patients with lung cancer: implications for the evaluation of palliative treatment. Br J Cancer 71(3):633–636. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.1995.124

Giroux Leprieur E, Labrune S, Giraud V, Gendry T, Cobarzan D, Chinet T (2012) Delay between the initial symptoms, the diagnosis and the onset of specific treatment in elderly patients with lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer 13(5):363–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cllc.2011.11.010

Gonzalez-Barcala FJ, Falagan JA, Garcia-Prim JM, Valdes L, Carreira JM, Pose A, Canive JC, Anton D, Garcia-Sanz MT, Puga A, Temes E, Lopez-Lopes R (2014) Symptoms and reason for a medical visit in lung cancer patients. Acta Medica Port 27(3):318–324

Cleeland CS (2014). The MD Anderson Symptom Inventory user guide. Department of Symptom Research, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. https://www.mdanderson.org/documents/Departments-and-Divisions/Symptom-Research/MDASI_userguide.pdf. Accessed April 2, 2018

Buchanan DR, White JD, O’Mara AM, Kelaghan JW, Smith WB, Minasian LM (2005) Research-design issues in cancer-symptom-management trials using complementary and alternative medicine: lessons from the National Cancer Institute Community Clinical Oncology Program experience. J Clin Oncol 23(27):6682–6689. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.10.728

Sloan JA, Loprinzi CL, Kuross SA, Miser AW, O’Fallon JR, Mahoney MR, Heid IM, Bretscher ME, Vaught NL (1998) Randomized comparison of four tools measuring overall quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 16(11):3662–3673. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1998.16.11.3662

Serlin RC, Mendoza TR, Nakamura Y, Edwards KR, Cleeland CS (1995) When is cancer pain mild, moderate or severe? Grading pain severity by its interference with function. Pain 61(2):277–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(94)00178-H

Anderson KO (2005) Role of cutpoints: why grade pain intensity? Pain 113(1–2):5–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2004.10.024

Cleeland CS, Sloan JA, Cella D, Chen C, Dueck AC, Janjan NA, Liepa AM, Mallick R, O’Mara A, Pearson JD, Torigoe Y, Wang XS, Williams LA, Woodruff JF (2013) Recommendations for including multiple symptoms as endpoints in cancer clinical trials: a report from the ASCPRO (Assessing the Symptoms of Cancer Using Patient-Reported Outcomes) Multisymptom Task Force. Cancer 119(2):411–420. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.27744

Palos GR, Mendoza TR, Mobley GM, Cantor SB, Cleeland CS (2006) Asking the community about cutpoints used to describe mild, moderate, and severe pain. J Pain 7(1):49–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2005.07.012

Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Cleeland CS, Morrissey M, Johnson BA, Wendt JK, Huber SL (1999) The rapid assessment of fatigue severity in cancer patients: use of the Brief Fatigue Inventory. Cancer 85(5):1186–1196. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990301)85:5<1186::AID-CNCR24>3.0.CO;2-N

Mendoza TR, Laudico AV, Wang XS, Guo H, Matsuda ML, Yosuico VD, Fragante EP, Cleeland CS (2010) Assessment of fatigue in cancer patients and community dwellers: validation study of the Filipino version of the brief fatigue inventory. Oncology 79(1–2):112–117. https://doi.org/10.1159/000320607

Cleeland CS, Body JJ, Stopeck A, von Moos R, Fallowfield L, Mathias SD, Patrick DL, Clemons M, Tonkin K, Masuda N, Lipton A, de Boer R, Salvagni S, Oliveira CT, Qian Y, Jiang Q, Dansey R, Braun A, Chung K (2013) Pain outcomes in patients with advanced breast cancer and bone metastases: results from a randomized, double-blind study of denosumab and zoledronic acid. Cancer 119(4):832–838. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.27789

Hubbard JM, Grothey AF, McWilliams RR, Buckner JC, Sloan JA (2014) Physician perspective on incorporation of oncology patient quality-of-life, fatigue, and pain assessment into clinical practice. J Oncol Pract 10(4):248–253. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2013.001276

AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (2017) 8th edn. Springer International Publishing, Cham

Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, Blinderman CD, Jacobsen J, Pirl WF, Billings JA, Lynch TJ (2010) Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363(8):733–742. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1000678

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Jeanie F. Woodruff, BS, ELS, for editorial assistance. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Funding

All research at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center is supported in part by the institution’s Cancer Center Support Grant, NCI P30 CA016672. The sponsors played no role in study design, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Tito Mendoza: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing

Kenneth Kehl: conceptualization, investigation, and writing—review and editing

Oluwatosin Bamidele: conceptualization, investigation, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing

Loretta Williams: conceptualization, investigation, and writing—review and editing

Qiuling Shi: data curation, methodology, and writing—review and editing

Charles Cleeland: conceptualization, investigation, resources, supervision, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing

George Simon: conceptualization, investigation, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The study was approved by our Institutional Review Board. As this was a retrospective review of deidentified data, the requirement for informed consent was waived.

Conflict of interest

The MD Anderson Symptom Inventory is copyrighted and licensed by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and Charles S. Cleeland. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Précis

We assessed pretreatment symptom severity in 460 patients with lung cancer; one third were already experiencing moderate-to-severe symptoms (especially fatigue, disturbed sleep, distress, pain, dyspnea, sadness). Because poorly controlled symptoms can disrupt treatment adherence and therapeutic outcomes, baseline symptom assessment and early supportive care to palliate these symptoms are needed.

Tweet

Patients with lung cancer already experience moderate/severe symptoms (especially fatigue, disturbed sleep, distress, pain, shortness of breath, sadness) before they begin treatment. Early assessment and supportive care to palliate these symptoms are needed.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mendoza, T.R., Kehl, K.L., Bamidele, O. et al. Assessment of baseline symptom burden in treatment-naïve patients with lung cancer: an observational study. Support Care Cancer 27, 3439–3447 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4632-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4632-0