Abstract

In this paper, we try to understand what considerations and possible sources of inspiration Desargues used to formulate his concepts of involution and transversal, and to state the related theorems that are at the basis of his Brouillon project. To this end, we trace some clues which are found scattered throughout his works, we connect them together in the light of his experience and knowledge in the field of perspective, and we investigate what were his motivations within Mersenne’s academy. As a result of our research, we can safely say that were his great geometrical insight and his projective vision of space which, guided by some classical theorems, led him to these completely new concepts in the panorama of the geometry of that time that were destined to remain misunderstood for about two centuries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The only known copy to date of the Brouillon project is preserved in the National Library of France, and available on Gallica website. For the history of its discovery, see (Taton 1951a).

In his 1654 address to the Academy, Blaise Pascal referred to it as “Celeberrima Matheseos Academia Parisiensis”, see Oeuvres Complètes de Pascal, Ch. Bossut Ed.,1779, V, p. 459.

In the very late 1630s, also his son Blaise attended to the meetings.

See Del Centina (2016).

The chords theorem amounts to the following (Fig. 1a): For any pair of parallel chords of a conic section BC, ED, which are cut by another chord AA′ at point H, K, respectively, the equation \((BH\times HC)(AK\times K{A}^{\text{'}})=(EK\times KD)(AH\times HA')\) holds true. See also later on in this section. For the history of this theorem, see (Del Centina and Fiocca 2021).

This letter has been published in Taton (1951b, 80–86).

Letter of Carcavy to C. Huygens of June 1656, an extract of which is published in Taton (1951b).

In the letter to Mersenne, Desargues informed him of having told Mydorge of his own achievements on conic sections. See Appendix 2.

In the above-mentioned letter to Mersenne, Desargues asked for having Descartes’s explanation on certain arguments treated in the Géométrie, thus showing to have read it at least in part. See again Appendix 2.

This has been translated into English in Field and Gray (1987), and to this, we refer for any detail.

“Aiant à pourtraire une coupe de cóne plate, y mener deux lignes, dont les apparences soient les essieux de la figure qui la représentera”.

By complete quadrilateral, it is understood the set of six straight lines joining two-by-two the four vertices of a quadrangle.

For these terms, and of some passages from the Brouillon project, we have used the English translation of this work provided in Field and Gray (1987).

The list of errata and addenda of four pages that Desargues added after the printing, to which we will refer as “Notice”.

For details, we refer to Theorem 5.1 in Anglade and Briend (2017).

Actually, Desargues attempted, proceeding by absurdity, to prove that the notion of involution implies that of tree, but his reasoning was incomplete. Anglade and Briend have shown how to complete the proof by applying an argument that Desargues had used a few lines higher in the Brouillon (Anglade and Briend 2017, Theorem 5.2). We shall return on this argument at the end of Sect. 6.

We recall that an involution of the projective line can be hyperbolic, elliptic, or degenerate. In the first case, there are two fixed points (Desargues’s mean double knots), while in the second, there are not fixed points.

According to Anglade and Briend is this property that justifies the introduction of the concept of involution.

Actually, Desargues meant a conic section intersecting the straight line. This is clear when, completing the proof of the theorem, he considered the case in which the four points lie on a circle and stated “Quand don’t ces quatre bornes B, C, D, E, sont au bord d’un cercle qui rencontre en L, M, cette septiesme quelconque droicte GPH” (1639, 17, l. 8_). See Sect. 5.

If the straight line is given at will, not every conic section through the four points B, C, D, E cuts real points on it, so we think that Desargues referred to any conic section intersecting, or touching, the given line.

We point out that stating and proving this and other theorems, Desargues used proportions and composition of proportions; for simplicity, we often translate them in the form of equality of ratios, and their products.

See also (Anglade and Briend 2018).

For their statements, we use the English translation provided by Field and Gray in (1987, 161–169).

This straight line is missed in the original text; see (Field and Gray 1987).

As we have said in Sect. 1, Desargues referred to this theorem as “Ptolemy’s theorem”, but today is better known as Menelaus’s theorem, or Menelaus and Ptolemy’s theorem. It is useful to remind it: If AB, AG are two straight lines, and BE, GD are other two straight lines intersecting at F, then the relations \(\frac{EG}{EA}=\frac{FG}{FD}\times \frac{BD}{BA}\ and\ \frac{AG}{AE}=\frac{DG}{DF}\times \frac{BF}{BE}\) hold true. Each of these relations can be used to prove the collinearity of three points lying on the prolongation of the sides of a triangle.

We observe that, if K does not belong to the plane of the quadrangle OABD, this is equivalent to the choice of a plane through o and the line 857432.

The plane of the quadrangle OABD, which we can call “base plane”; that of the quadrangle oabd, which we can call “plane of section” (the plane o235), the six planes through each of the six sides of the complete quadrilateral associate with OABD, which we may distinguish in four “faces” and two “diagonal planes”. It is readily seen that any three of these plane meet in a same point, which can be at a finite or at an infinite distance, as, for instance, when K is at infinity, or a side of the complete quadrilateral is parallel to the plane of section.

See for instance (Briend 2021, 729–730).

According to the definition given in Sect. 2, this means that the three pairs of points 2,7; 3,4; 5,8 are in involution.

That is, that the three pairs of points in which a straight line is cut by the sides of a complete quadrilateral are in involution.

“On l'on void que c'est une mesme propriété de trois couples de rameaux déployez au tronc d'un arbre quand il sont tous d'une mesme ordonnance entre eux, et quand ils sont disposez comme icy aux quatre poincts B, C, D, E, de façon que le but de l'ordonnance de trois couples de rameaux est comme si ces quatre poincts B, C, D, E, s'unissoient à un seul poinct”, (1639, p.17, l. 28^).

“Que si les deux bornales d'une couple BCN, EDN, sont paralelles entre elles, le rectangle des brins désployez IC, IB, est à son relatif le rectangle KD, KE comme le rectangle de la couple de quelconques brins pliez au tronc IQ, IP, gemeau du rectangle IB, IC est à son relatif le rectangle de brins pliez au tronc KQ, KP, gemeau du rectangle KD, KE, ce qui est évident du paralelisme de ces rameaux ou bornales entre elles BC, DE” (1639, p.17, l. 32–36^).

On this argument, see (Del Centina and Fiocca 2021).

See Del Centina (2020).

See Pappus (1588, 146r–147r).

The claim is proved in Commandino’s commentary (Pappus 1588, 147r–147v).

“Et quand les bornes B, C, D, E sont au bord courbe d’une quelconque autre espece de coupe de Rouleau, sans faire icy tant de figures pour un simple Brouillon de projet, si l’on se veut donner le divertissement d’en faire ailleurs, on verra que le rouleau duquel cette figure et coupe estant restably sur elle, et en suitte sur son assiette ou base le quelconque cercle BCDE” (1639, 18l.12^).

“Cette demonstration bien entenduë s’applique en nombre d’occasions et fait voir la semblable generation de chacune des droits et de points remarkables en chaque espece de coupe de Rouleau, et rarement une quelconque droicte au plan d’une quelconque coupe de Rouleau peut avoir une propriété considerable à l’égard de cette coupe, qu’au plan d’une autre coupe de ce rouleau la position et les propriétéz d’une droicte correspondant à celle-là ne soit aussi donnés par une semblable construction de ramée d’une ordonnance dont le but soit au sommet du rouleau. Droictes ordonnées à un mesme tel but, c’est-à-dire, qui passent ou tendent emsembles à ce but” (1639, 18l.40^); the latter sentence is added in the Notice.

In this figure, as in Fig. 12, the quadrilateral BCDE is convex, but things do not change if it is not.

To facilitate interpretation, we have indicated in the square brackets the points which in Fig. 14 correspond to those in Desargues’s text.

See Anglade and Briend (2017) for the details.

See the proof of Theorem 5.2 in Anglade and Briend (2017). As already said in the footnote 26, Desargues’s proof of the equivalence between the notion of tree and involution was incomplete, but in the just quoted paper, the two authors show how to recuperate it by applying an argument Desargues had previously used in another situation.

It is useful to recall what Desargues wrote in the letter he addressed to Mersenne in April 1638; see Appendix 2.

This is the full name given by Desargues. As we have already said, this concept is equivalent to that of “polar” of a point with respect to a conic section.

Desargues did not specify “of four points”, so we understand that each set of four points constitute a harmonic division.

He was referring to the two types of involution with two mean double knots and two mean simple knots, and he had already described in case of an involution defined by a pencil of conic sections.

Observing Fig. 10b, we see that the straight line NG corresponds to the chord of contact of the tangents to the conic section issuing from F. However, Desargues did not mention this fact until p. 22.

We observe that the fourth harmonic G of a point F exterior to a conic section with respect to the points in which an ordinate of butt F (as FM) meets that curve describes a straight line, when the ordinate varies in the ordinance; it follows from Conics, III, prop. 37 and the uniqueness of the fourth harmonic point.

The phrase in Italic was added in the Notice.

It has been pointed out by Anglade and Briend (2019, Sect. 3.3) that Desargues’s proof was incomplete. We shall not discuss this matter here, referring to the article just quoted for the details.

The correct ordering is “N, Z, A”.

We observe that the stump coincides with the intersection point of NG with the diameter of the circle orthogonal to NG; in fact, in this case, the tangents at the extremities of the diameter are parallel to NG, i.e., the point N is at infinity.

“D’où suit qu’autant de couples de droictes qui sont ordonnées à un des poincts du bord de lacoupe de rouleau, et qui passent aux deux poincts du mesme bord qu’y donne une quelconque droicte d’une quelconque ordonnance, donnent en la traversale de cette ordonnance autant de couples de noeuds d’une involution” (Desargues 1639, 22, l.22^).

Desargues (1639, 5, line 9 from below).

Idem, p. 29, line 6 from below. It is worth noticing that the propositions announced in Pascal’s (1640) were five.

Translation from an extract of Desargues’s letter to Mersenne, recorded in Appendix 2.

On the re-discovering of Desargues’s and Pascal’s results in the early nineteenth century, see (Del Centina 2022).

This seems to suggest the use of practical procedures and experiments.

In the Notice Desargues explained “Les plus remarquables proprietez des coupes de Rouleau, sont communes à toutes les especes et le noms d’Ellipse, Parabole, et Hyperbole, ne leur ont esté donnes qu’à raison d’evenemens qui sont hors d’elles et de leur nature”, second page at line 19.

References

Aguilon, F. 1613. Opticorum libri sex philosophis juxta ac mathematicis utilis, Antuerpae, Ex Officina Plantiniana, apud Viduam et Filios Io. Moreti.

Andersen, K. 2007. The geometry of an Art; the History of the Mathematical theory of Perspective from Alberti to Monge. New York: Springer.

Anglade, M., and J.-Y. Briend. 2017. La notion d’involution dans le Brouillon Project de Girard Desargues. Archive for History of Exact Sciences 71: 543–588.

Anglade, M., and J.-Y. Briend. 2018. L’usage de la combinatoire chez Girad Desargues: le cas du théorème de Ménélaüs.

Anglade, M., and J.-Y. Briend. 2019. Le diamètre et la traversale: dans l’atelier de Girad Desargues. Archive for History of Exact Sciences 73: 385–426.

Anglade, M., and J.-Y. Briend. 2022. Nombrils, bruslans, autrement foyez: la géométrie projective en action dans le Brouillon Project de Girad Desargues. Archive for History of Exact Sciences 76: 173–206.

Apollonius. 1566. Conicorum libri quatuor, una cum Pappi Alexandrini lemmatus et commentariis, Bonomiae, ex Officina A. Benatii.

Apollonius. 1626. Apollonii Pergaei conicorum et Sereni de sectione coni et cylindri libri…, Editit Marinus Mersenne, Lutetiae, ex Typographia N. Caroli.

Barozzi, I. 1583. Le due regole dellaa prospettiva pratica di Iacomo Barozzi da Vignola, con I commentary del R.P.M. Ignatio Danti dell’ordine de Predicatori Matematico dello Studio di Bologna. Roma: F. Zanetti.

Beaugrand, J. 1636. Geostatice seu de vario pondere gravitum secundum varia terrae intervalla dissertation mathematica. Paris: T. du Bray.

Benedetti, G.B. 1585. Diversarum speculationum mathematicorum et physicarum liber, Taurini, apud N. Bevilaquae.

Bosse, A. 1648. Maniere universelle de Mr. Girard Desargues, pour pratiquer la perspective par petit-pied, comme le Geometral, Paris.

Briend, J.-Y. 2021. Mathématiques en perspective: Desargues, la Hire, le Poivre. Archive for History of Exact Sciences 75: 669–729.

Catastini, L., and F. Ghione. 2005. Nella mente di Desargues tra involuzioni e geometria dinamica. Bollettino Dell’unione Matematica Italiana, Sez. A 8 (1): 123–147.

Chaboud, M. 1994. Deasrgues Lyonnais. In Desargues and son temps, ed. J. Dhombres and J. Sakarovitch, 55–85. Paris: Librairie Scientifique A. Blanchard.

Del Monte, G. 1600. Perspective libri sex. Pisauri, Apud Hieronymum Concordiam.

Del Centina, A. 2016. On Kepler’s system of conics in Astronomiae par optica. Archive for History of Exact Sciences 70: 567–589.

Del Centina, A. 2020. Pascal’s mystic hexagram, and a conjectural restoration of his lost treatise on conic sections. Archive for History of Exact Sciences 74: 469–521.

Del Centina, A. 2022. Carnot’s theory of transversals and its applications by Servois and Brianchon: the awakening of synthetic geometry in France. Archive for History of Exact Sciences 76: 45–128.

Del Centina, A., and A. Fiocca. 2021. The chord theorem recalled to life at the turn of the eighteenth century. Historia Mathematica 56: 6–39.

Desargues, G. 1636. Exemple de l’une de manières universelles de S.G.D.L. touchant la pratique de l perspective sans emploier aucun tiers point, de distance ny d’autre nature, qui soit hors du champ de l’ouvrage, Paris.

Descartes, R. 1637. La Géométrie. In Discours de la Méthode, pour bien conduire sa raison et chercher la vérité dans les sciences etc. ed. R. Descartes. Leide, Maire.

Desargues, G. 1639. Brouillon project d’une atteinte aux evenements des rencontres du Cone avec un Plan, Paris.

Dhombres, J. 1994. La culture mathématique au temps de la formation de Desargues: le monde des coniques. In Desargues and son temps, ed. J. Dhombres and J. Sakarovitch, 55–85. Paris: Librairie Scientifique A. Blanchard.

Field, V. 1987. Two Mathematical Inventions in Kepler’s Ad Vitellionem paralipomena. Studies in History and Philosophy of Sciences 15: 1–19.

Field, J.V., and J. Gray. 1987. The geometrical work of Girard Desargues. New York: Springer.

Grégoire, M. 1992. La querelle entre Descartes et Fermat a propos des tangentes. Mnémosine 2, Université Paris VII, 29–57.

Hogendijk, J. 1991. Desargues’ Brouillon project and the conics of Apollonius. Centaurus 34: 1–43.

Kepler, J. 1604. Ad Vitellionem paralipomea quibus astronomiae pars optica traditur. Francofurti, C. Marnium et H.I. Aubrii.

Le Goff, J.-P. 1994. Desargues et la naissance de la géométrie projective. In Desargues and son temps, ed. J. Dhombres and J. Sakarovitch, 55–85. Paris: Librairie Scientifique A. Blanchard.

Lenger, F. 1950. La Notion d’Involution dans l’Oeuvre de Desargues. In IIIe Congrès National des Sciences, Bruxelles, 27–30.

Maurolico, F. 1611. Photismi de lumine, et umbra ad perspectivam, et radiorum incidentiam facienda. Neapolis, T. Longi.

Maurolico, F. 1613. R.D. Theoremata de lumine et umbra ad perspectivam, et radiorum facienda, his accesserunt Christofori Clavji a Societate Jesu notae, Lugduni, Apud B. Vincentium; reprinted in 1617.

Mersenne, M. 1636. Harminie universelle, contenant the theorie et la pratique de la musique. Paris: chez S. Cramoisy.

Mydorge, C. 1631. Prodromi catoptricorum et dioptricorum: sive conicorum operis ad abdita radii reflexi et refracti mysteria praevij et facem praeferentis, libri primus et secundus quatuor priores. Parisiis, I. Dedin.

Mydorge, C. 1639. Prodromi catoptricorum et dioptricorum: sive conicorum operis ad abdita radii reflexi et refracti mysteria praevij et facem praeferentis, librii quatuor priores. Parisiis, I. Dedin.

Pappus, 1588. Pappi Alexandrini Mathematicae Collectiones, a Federico Commandino Urbunate latinum conversae et Commentatiis illustratae. Pisauri, apud H. Concordiam.

Pappus. 1610. Pappi Alexandrini Mathematicae Collectiones, a Federico Commandino Urbunate latinum conversae et Commentatiis illustratae, In hac nostra editione ab innumeris, quibus scatebant mendis, et praecipuè in Graeco context diligentes vindicate. Bonomiae, Ex Typographia HH. De Duccijs.

Pascal, B. 1640. Essay pour les coniques, Paris.

Poudra, N.-G. 1864. Oeuvres de Desargues réunies et analysées, Paris.

Taton, R. 1951a. Découverte d’un exemplaire original du Brouillon project” sur les Coniques de Desargues. Revue D’histoire Des Sciences 4–2: 176–181.

Taton, R. 1951b. L’œuvre mathématique de G. Desargues, textes publiés et commentés avec une introduction biographique et historique. Paris: Presses Univ. de France.

Taton, R. 1962. L’œuvre de Pascal en géométrie projective. Revue D’histoire Des Sciences Et De Leurs Applications 15 (3–4): 197–252.

Taton, R. 1994. Desargues et le monde scientifique de son époque. In Desargues and son temps, ed. J. Dhombres and J. Sakarovitch, 55–85. Paris: Librairie Scientifique A. Blanchard.

Viète, F. 1600. Apollonius Gallus. Parisiis, D. le Clerc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Jeremy Gray.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

1.1 Desargues’s geometrical propositions and concept of transversal rooted in perspective

One of the basic problem in perspective was to draw correct images of simple plane figures, as triangles, quadrilaterals, and circles; and the theoretical perspective, which developed in the late sixteenth century, aimed at giving mathematical evidence to support the experimental techniques of practitioners. In Giovanni Battista Benedetti’s Diversarum (1585) and Guidobaldo del Monte’s Perspective libri sex (1600), which according to Andersen (2007) greatly influenced theorists of perspective in the seventeenth century, geometrical constructions are found concerning the aforementioned issues, which were also re-proposed some years later in François Aguilon’s treatise (1613), a widespread book in the Flanders and France. We believe that these constructions, and the related figures, were an inspiration for Desargues in conceiving the first two geometrical propositions and the notion of the transversal of an ordinance of lines.

The first one we consider is the one del Monte provided for proposition VI in Book II, concerning the drawing of the perspective image in the plane of picture VBO of the triangle CDE, as seen from the eye A. The related original figures, here reproduced in Fig. 19a, b, make clear that the corresponding sides of the two triangles (or their prolongations) meet along the ground line BO.

a Reproduces the figure for proposition VI in del Monte (1600, 62), for the construction of the image LMN of the triangle CDE on the plane VBO seen from the eye A. The two triangles in perspective are not emphasized in the original figure. b Reproduces the figure illustrating the “praxis” for the previous construction (del Monte 1600, 63). The dashed lines, not drawn in the original figure, make clear that the two triangles are in perspective with respect to the eye A

The second construction we want draw attention to is related to the perspective image of a (complete) quadrilateral in a plane not orthogonal to the ground plane as described in Benedetti (1585), and illustrated in his figure D, here reproduced in Fig. 20.

Reproduces the figure “D” in Benedetti (1585), showing two (complete) quadrilaterals in perspective from the eye o, uadq and its image ercm, whose sides, or prolongations, meet along the ground line qx. In this figure, we have added the tiny straight lines not drawn in the original figure, and marked μ, φ, ϕ, ϛ the corresponding points of intersection

This figure, which clearly represents the vertical version of the same construction as performed with the “sportello”—an instruments often used by the practitioners of perspective (Andersen 2007)—shows, or at least suggests, that the corresponding sides (or their prolongations) of two perspective quadrilateral meet along the ground line.

Although we cannot claim that Desargues knew del Monte and Benedetti’s works, these constructions, or similar ones which found place in various manual on perspective after (Barozzi 1583), did not escape to him (Fig. 21).

Finally, we want to mention another very inspiring construction which is presented in del Monte (1600, 217), and in Aguilon (1613, 669), regarding the perspective image of a circle, and whose related figure is here reproduced in Fig. 22. Without entering into a detailed description of such a construction, for which we refer the reader to the just-mentioned works, we briefly comment on the figure illustrating it, but having in mind that Desargues was not only well versed in the art of perspective but also an expert geometer accustomed to dealing with points at infinity.

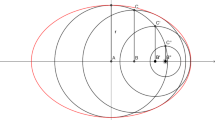

When the circle BCDE is represented in the plane of picture GRVX as seen from the “eye” A, parallel tangents to the circle are projected in converging tangents to its image; to the directions, CG and DF correspond the vanishing points V and X, respectively, and so, the line at infinity of the plane of the circle is projected in the line VX of the plane of picture; the centre H of the circle, “pole” of the line at infinity with respect to the circle, is projected in the point Q, “pole” of the straight line VX with respect to the conic section image of the circle. All this appears very clear if one keeps to mind the figure IV attached to the Brouillon project (Fig. 12).

As the ordinates of a general ordinance are divided in equal parts by the orthogonal diameter WHW′ of butt Σ∞, and vice versa, the corresponding points on the image, as w, Q, w′, Σ form a harmonic set. This is graphically illustrated in Fig. 23, which also shows that since the fourth harmonic point of the centre of a circle (which divides in two equal parts any diameter) with respect to any two diametrical points lies on the line at infinity, the fourth harmonic of their perspective images lie on the horizon line XV.

This diagram is an advanced version of the figure in del Monte (1600, 217), giving the construction of the perspective image of a circle from the eye A in the plane of picture YXVR. We see that the centre H of the circle, pole of the line at infinity of the ground plane, in which lie the butt Y∞ of the straight lines GC, YL, ID, etc. and the butt Z∞ of the straight lines FD, ZC, etc., is projected onto the point Q “pole” of the straight line XV, into which the line at infinity is transformed. To the polars ID and CZ, of the points Z∞ and Y∞, correspond the polars IV and XZ, of the points X and V, respectively

We cannot fail to say that Fig. 22 brings to mind the phrase, here reported in Sect. 1, with which Desargues ended his first essay on perspective (1636).

Often in geometry, a drawing can say more that many words.

Therefore, we believe that also the theory of the transversal of an ordinance of straight lines (that is of “polar”) that Desargues expounded in the Brouillon project found its origin in the practice of perspective (Fig. 23).

Appendix 2

2.1 Extracts from Desargues’s letter to Mersenne

In this second appendix, we record and briefly comment upon some extracts from the letter that Desargues addressed to Mersenne on the 4th of April 1638. As already said, Desargues wrote this letter on the occasion of returning to Mersenne a certain manuscript of Descartes, that the Minim had given him to read. The main object of the letter concerned the dispute between Descartes and Fermat about their different methods for constructing the tangents to a conic section from a given point outside the curve, or at a point on it, and also the motivations that Roberval and Étienne Pascal had made known to him in support of Fermat’s thesis. Much of the question regarded the use of specific properties of the curves in question, and Fermat’s methods for treating the cases of the ellipse and of the parabola separately. We do not enter here in technical details about this subject, referring for them to Grégoire (1992), but we notice that Desargues took the opportunity to express his own opinion on the controversial matter, and in doing that to stress his view about the concept of “general method” for the problems concerning conic sections, and, above all, to anticipate some of his achievements in this field.

Desargues did not share Roberval and Pascal’s opinion, and giving more credit to Descartes he specified:

Selon ma maniere de proceder universelle j’auray raisonné selon cette façon, tant au sujet de la parabole que de l’autres coupes de cone, comme estant une chose commune a toute les coupes [dont je scay bien que ils n’ont pas accoustumé de faire mention comme d’une proprieté generalement commune a toutes coupes, mais ils en font deux especes de proprietez, une particuliere a la parabole et l’autre particuliere aux autres coupes où je voy qu’il n’ont pas…]Footnote 65

thus, according to Desargues, as regard the question of tangents, one should look at the ellipse and the parabola as the same kind of curve, because tangency had to be treated in the same way for all conic sections. In fact, few lines below he added:

car si la methode est generale les mesmes motz exprimants une mesme proprieté doivent convenier et servir a chacune espece de coupe.

Then, Desargues continued by saying that he had told Mydorge how he was surprised in seeing that such well-versed mathematicians had a veil in front their eyes:

qui leur face constituer un genre particulier de ligne des seules touchantes aux coupes de cone, different en toutes choses d’avec celles qui traversent les mesme coupe de cone quand ces lignes (que j’entens droites) viennent d’un mesme poinct.

Desargues, alluding to his theory of the transversal of an ordinance of lines (polarity) as will be clear shortly, meant that tangents should not be distinguished from secants when all these straight lines belong to the same ordinance; in fact, he continued by saying:

Et moy que vous scavez qui n’ay de connoissance de ces matieres que pour mes propres et particulieres contemplations, je m’enhardy lors de dire à M. Mydorge, contre son attente et son opinion, que par mes contemplations capricieuse du cone rencontré par divers plans en toute façons, et des lignes et des figures qui s’engendrent en cette rencontre,Footnote 66 j’ay trouvé que par un seul et mesme enonciation, constrution et preparation ou pour dire mieux par un seul et mesme discours et sous de mesmes paroles, on declare un moyen de construire ou bien on declare les moyens de faire une construction d’un autre ordre par lequelle on voit egalement une pareille generation en toutes especes de plates coupes de cone, de toutes especes de lignes droites qui ont et reçoivent des ordonnés, comme diametres et autre, et l’on voit semblablement une pareille generation en chaque espece de plate coupe de cone, de toute les especes d’ordonnées qu’il y a pour chaque espece de lignes qui reçoivent des droites ordonnées. Et l’on voit une pareille generation à mesme temps de toutes leurs touchantes, chacune de ces touchantes estant membre d’un des corps de ces diverses especes d’ordonnèes.

As Taton remarked (1951a, 84, footnote 1), Desargues was referring to his notion of ordinates as the straight line passing through the “pole” of a straight line given in the plane of the conic section, which generalizes the notion of ordinates with respect to a diameter of the curve, all parallel to the direction of the conjugate diameter. He went on writing:

Et semblablement par un autre seul et mesme discours et constrution on voit une pareille generation en chaque espece de coupe de cone, des pointz qu’on nomme foyers, et en suite leur situation et quelquez proprietez commune entre eux en chaque espece de coupe de cone. Le tout sans faire bande a part pour la parabole et sans en exclure le cercle, non plus pour les foyers que pour les diverses especes des droites qui reçoivent des ordonnées, ny pour les diverses especes d’ordonnées.

Therefore, in his study of conic sections, which aimed at expounding their common properties, Desargues did not distinguish them in kinds,Footnote 67 and did not consider the parabola and the circle as separate cases, neither for the foci nor for the various species of straight lines which generalize the diameters and their ordinates.

We also understand that Desargues, like Kepler before him, admitted the second focus of the parabola, which though placed at infinity enjoyed the same properties as the ordinary ones.

Remarking the novelty of his method for treating conic sections, Desargues wanted to point out:

Et aussi sans employer pour cela aucun des triangles par l’essieu ny faire distinction d’un principal diametre d’avec les autres entre lesquels on distingue nettement les essieux en chaque figure. Je scay bien qu’ils n’ont faict mention que d’une seule espece de lignes qui reçoivent des ordonnées assavoir les diametres seulement en chaque figure, et d’une seule especes d’ordonnées en chaque figure, de quoy je m’estonne car je trouve que dans un mesme genre il y a deux especes de chaqune de ces sortes de ligne.

It is evident that some of mean Desargues’s geometric conceptions were already outlined at the beginning of 1638, as the fruit of his own particular and capricious contemplations of the sections of cone by different planes in whatever position, and of the lines and curves which these sections generate. We cannot but think to his Leçons de ténèbres, and we wonder whether his “contemplations” referred also to optical experiments he may have conducted.

Afterward, Desargues returned to discuss the objections Fermat had raised to Descartes’s method for the determination of the tangents to a curve as expounded in the Géométrie, and the opinion that Mydorge expressed in this regard, to conclude that his thinking was closer to that of Descartes than Fermat. At the end of the letter, Desargues wrote:

Quand à sa Geométrie [Descartes’s] j’en entens quelque chose, mais si j’osoy l’en importuner ou vous, je seroy bien aise d’en avoir un peu de plus familière explication pour mon esprit grossier, et puisque l’auteur est vivant, estre délivré du travail necessaire à son deffault pour m’ajuster asseurement à sa pensée notamment dès l’entrèe de la matiere. Et quoy que disent nos Mess.rs de Beaugrand et autres, j’ay suject de supçonner qu’ils ne entendent pas a fonds, je veus dire qu’ils ne possedent pas bien plainement toutes les intuitions de Monsieur des Cartes au suject de sa Geometrie.

These final words suggest that, although not all of Descartes’s Géométrie was clear to him, Desargues perceived its spirit and importance, and saw, with some regret, the profound incursion of algebra into geometry; but also that he was eager to go more deeply into the matter.

From the letter as a whole, it seems that Desargues’s desired to demonstrate publicly that his general methods allowed one not only to get where the application of algebra had conducted geometry, but also beyond.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Del Centina, A. Desargues’s concepts of involution and transversal, their origin, and possible sources of inspiration. Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 76, 573–622 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00407-022-00296-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00407-022-00296-5