Abstract

This paper describes Alfred Clebsch’s 1871 article that gave a geometrical interpretation of elements of the theory of the general algebraic equation of degree 5. Clebsch’s approach is used here to illuminate the relations between geometry, intuition, figures, and visualization at the time. In this paper, we try to delineate clearly what he perceived as geometric in his approach, and to show that Clebsch’s use of geometrical objects and techniques is not intended to aid visualization matters, but rather is a way of directing algebraic calculations. We also discuss the possible reasons why the article of Clebsch has been eventually completely forgotten by the historiography.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

“So erhält man als eine erste Anwendung der im Eingange der Abhandlung entwickelten allgemeinen Principien eine vollständige geometrische Uebersicht über die Zusammenhänge, welche zwischen den Gleichungen 5ten Grades und ihren Resolventen bestehen, insbesondere über den Zusammenhang mit der Jerrard’schen Form und der Modulargleichung” (Clebsch 1871b, 285).

The issue of visualization has been extensively studied by philosophers of mathematics: see Giaquinto (2007) and the references given in this book. See also the works of Valeria Giardino about cognitive aspects of the use of diagrams in specific parts of mathematics, for example in knot theory (Giardino and Toffoli 2013).

The authors of the obituary are the mathematicians Alexander Brill, Paul Gordan, Felix Klein, Jacob Lüroth, Adolf Mayer, Max Noether, and Karl von der Mühll. They present themselves as Clebsch’s “Freunde und ehemaligen Schüler” at the beginning of the text (Brill et al. 1873, 1). These mathematicians indeed worked closely with Clebsch, so they surely knew how he used to do mathematics.

“Clebsch war in erster Linie Algebraiker, und allen seinen Arbeiten gemeinsam ist die vollendete Beherrschung des algebraischen Apparates. Ihr zur Seite stellt sich in den späteren Untersuchungen die klare geometrische Auffassung, vermöge deren jeder Schritt, den die Rechnung vollführt, zu einem anschaulichen Verständnissse gebracht wird. Aber es ist nicht die concrete Art, die räumlichen Verhältnisse zu sehen, wie wir sie bei manchen anderen Geometern finden; die geometrische Anschauung ist ihm mehr Symbol und Orientirungsmittel für die algebraischen Probleme, mit denen er sich beschäftigt.”

That being said, I would like to stress that it does not mean that Clebsch did not use or praise visualization of geometrical objects in other contexts than the mentioned algebraic calculations. Moreover, let us note that Jemma Lorenat recently analyzed relations between geometry, algebraic computations, figures, and visualization in the first half of the nineteenth century (Lorenat 2015). Her study notably brings to light the role of equations as representatives of geometrical objects in Julius Plücker’s practice.

The paper was published in the fourth volume of the Mathematische Annalen, a journal which did include figures at that time (see for instance the 1873 volumes 6 and 7).

The authors of the obituary Brill et al. (1873) divide Clebsch’s research into six domains: mathematical physics; calculus of variations and the theory of first-order partial differential equations; the theory of curves and surfaces; the study of Abelian functions and their applications to geometry; representations of surfaces; invariant theory. According to these authors, the order of this list approximately reflects the chronology of Clebsch’s interests (Brill et al. 1873, 2).

This research is partially sketched in Gray (1989, 367–369) and Houzel (2002, 184–186). The book has been qualified by Igor Shafarevich as the “Zeugnis der Geburt der algebraischen Geometrie” and the “erster Schrei des Neugeborenen” (Shafarevich 1983, 136). Further, see also Rowe (1989, 188), where David E. Rowe talks about the “fledging school at Giessen that specialized in algebraic geometry and invariant theory.”

In modern terms, to represent an algebraic surface on the plane means to find a birational map between this surface and the projective plane.

Clebsch was again in competition with Dedekind (Dugac 1976, 133–134).

A list of Clebsch’s publications can be found in Brill et al. (1873, 51–55). It counts 107 items, among which four books of which he is (one of) the author(s) and two books that he edited on the basis of works of Plücker and of Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi. The other publications essentially divide into papers in the Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik (from 1856 to 1869) and in the Mathematische Annalen (from 1869 on).

Quotations of Hesse dated 1862 and reported in Dugac (1976, 133). Similar comments from other mathematicians can be found in this reference and the ones that were quoted above. Other statements also emphasize Clebsch’s pedagogical qualities.

For reasons that will be explained below, the paper does appear in a few historical works related on the geometry of cubic surfaces.

About the research on the icosahedron, see Gray (2000). Moreover, some historians have analyzed in detail the works of Hermite and Kronecker on the quintic: see Goldstein (2011) and Petri and Schappacher (2004), respectively. I will come back at length on these historical researches in the rest of the paper.

“Dans les années 1870, ce sujet était extrêmement à la mode et nous ne passons pas en revue tous les travaux qui y ont été consacrés, par A. Clebsch, P. Gordan, L. Kiepert par exemple, avant que F. Klein ne s’y intéresse” (Houzel 2002, 80).

“Dabei ergiebt sich zugleich eine Reihe bemerkenswerther rein geometrischer Resultate, welche geeignet scheinen, die Fruchtbarbeit [sic] der entwickelten Anschauungen und Methoden darzuthun” (Clebsch 1871b, 285).

In the paper, Clebsch never commented on the nature of the coefficients (which could be rational, real, or complex for instance).

Therefore, Clebsch’s “transformations” are not transformations of the plane or the space such as rotations or translations. Moreover, the significance of what he called “substitutions” differs from that of “substitutions” as in the phrase “the theory of substitutions,” which refers to what is now called “permutations.”

“Aber an diese Darstellung knüpft sich eine geometrische Interpretation” (Clebsch 1871b, 285).

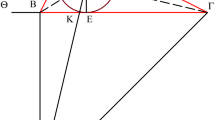

Here, \(z_1,z_2,z_3\) designate the homogeneous coordinates of the plane. The line (xy) has the parametric equations

$$\begin{aligned} \left\{ \begin{array}{l} z_1= y_1-\xi x_1 \\ z_2= y_2-\xi x_2 \\ z_3= y_3-\xi x_3. \end{array}\right. \end{aligned}$$Its intersection with the line defined by \(z_1+\lambda _i z_2+\lambda _i z^3=0\) is obtained for the parameter \(\xi \) satisfying the equality \((y_1-\xi x_1)+\lambda _i (y_2-\xi x_2)+\lambda _i ^2 (y_3-\xi x_3)=0\). According to the above, this parameter is the root \(\xi _i\) of the transformed equation.

“Wir erhalten hierdurch eine deutlichere Einsicht in das Wesen der quadratischen Substitution” (Clebsch 1871b, 286).

“Die Gesammtheit aller Gleichungen, in welche eine gegebene durch eine quadratische Substitution übergeht, entspricht den Schnittpunktsystemen der Geraden einer Ebene mit den Seiten eines gewissen Vielseits, dessen Seiten einen Kegelschnitt berühren.”

In Clebsch’s paper, one reads \(\xi '=\displaystyle \frac{\alpha +\beta \xi }{\gamma +\delta \xi }\), which seems erroneous.

“Es ist von grosser Wichtigkeit, dass hierdurch die in der höhern Transformation liegenden eigenthümlichen Elemente gesondert erscheinen von dem Einfluss, welchen eine nachträgliche lineare noch ausüben kann; und diese Eigenschaft giebt der vorliegenden Transformation und ihrer geometrischen Deutung vorzugsweise ihren Werth.”

It is important to emphasize that one can only replace what is replaceable: for instance, \(b_1\) does not appear alone in the substitution rules, and hence cannot be substituted—the only coefficients implying \(b_1\) that can be replaced are \(b_1^2\) and \(b_1b_2\).

Goldstein (2011, 248–249).

“Alle Geraden, welche ein gegebenes n-Seit so schneiden, dass für das Schnittpunktsystem eine gewisse Invariante \(\chi \) ten Grades verschwindet, umhüllen eine Curve (\(J=0\)) der Classe \(\chi n/2\). [...] Die Curve \(J=0\) hat die Seiten des n-Seits zu \(\chi \)fachen Tangenten.”

Clebsch used the letter f to designate both the binary form and this ternary form.

Here again, Clebsch used the same letter J twice: as an invariant of the binary form f, and as an invariant of the ternary form f.

Further explanations on modular equations are given below, in the case of the quintic.

Clebsch’s use of rational transformations can be seen as a trace of his geometrical approach, whereas Hermite’s use of polynomial transformations rather refers to an algebraic manner.

Hermite’s attention on adjunctions of square roots refers to the incorporation in his research of elements coming from Galois’ works (Goldstein 2011, 250).

To choose a projective frame of the plane is equivalent to choose a triangle of reference, of which the sides become the axis of vanishing of the coordinates. To bring the equations of the sides of a quadrilateral into the form announced by Clebsch, it is sufficient to choose the triangle formed by the three diagonals of the quadrilateral as the triangle of reference (a quadrilateral is a set of 4 lines; these lines intersect in six points and thus define three diagonals).

Let us recall that the degree of one of these equations is the class of the associated curve. Here we have curves of class 2, which correspond to the curves of degree 2, i.e., conics.

In this quotation, besides the works of Hermite, Clebsch also mentioned those of Gordan (1870). The latter had studied the vanishing of another invariant of the equation of degree 4.

“Man kann hieran in geometrischem Gewande die Lösung der Gleichung 4ten Grades knüpfen, wie Hermite (Comptes Rendus t. 46. p. 961) und Gordan (Borchardt’s Journal Bd. 71, p. 164) dieselbe gegeben haben. Diese Lösung beruht darauf, dass man die biquadratische Gleichung durch eine höhere Transformation in eine solche verwandelt, für welche i [...] verschwindet [...]. In der That braucht man nur das zu der Gleichung 4ter Ordnung gehörige Vierseit \(f=0\) zu nehmen, und [die Curve i=0 zu bilden. Diese] Gleichung zerfällt nach dem Obigen in 2 Kegelschnitte, eine Zerlegung, welche mit Hülfe einer quadratischen Gleichung ausgeführt wird; jede Tangente eines solchen Kegelschnittes mliefert dann eine biquadratische Gleichung, für welche \(i=0\) und welche also durch eine reine cubische Gleichung gelöst wird.”

In modern terms, if a conic is given by the vanishing of a quadratic form, its tangents are obtained thanks to the associated bilinear form. All these reflections appear very vaguely in Clebsch’s memoir.

In modern terms this group is \(\mathrm {PGL}(2,\mathbf {F}_n)\), which reduces to \(\mathrm {PSL}(2,\mathbf {F}_n)\) after the adjunction of a square root. The lowering of the modular equation seen by Galois then corresponds to the existence of a (non-normal) subgroup of \(\mathrm {PSL}(2,\mathbf {F}_n)\) of index n.

One can also find the names “Bring–Jerrard form” or “Tschirnhaus–Jerrard form” as Clebsch would write. See Beauville (2012) for a modern point of view linking this form with the essential dimension of the symmetric group \(S_5\).

The equation \(\varPhi ^5-\alpha \varPhi -\beta =0\) can be brought into the form \(\varPsi ^5-\varPsi -\alpha ^{-5/4}\beta =0\) when putting \({\varPhi =\alpha ^{1/4}\varPsi }\). The Jerrard form \(y^5-y-A=0\) being given, the next technical point is to find elliptic functions giving rise to some constants \(\alpha ,\beta \) satisfying \(A=\alpha ^{-5/4}\beta \). This had been established by Hermite with the help of an equation of degree 4 with coefficients in \(\mathbf {Q}[\sqrt{5}]\).

A covariant of a binary form \(f(x_1,x_2)\) is a polynomial expression \(K(a_0,\ldots ,a_n,x_1,x_2)\) involving the coefficients of f and the variables \(x_1,x_2\), such that for any invertible linear substitution acting on \(x_1,x_2\), one has \(K(a'_0,\ldots ,a'_n,\xi '_1,\xi '_2)=K(a_0,\ldots ,a_n,x_1,x_2)\), the notations being those previously given. In particular, a covariant is said to be linear when the variables \(x_1,x_2\) are involved linearly.

All these invariants and covariants were already listed in Hermite (1865–1866). A difference with Hermite is that Clebsch defined the invariants and covariants by means of the symbolic notation. For instance, denoting a quintic by \(f=a_z^5=b_z^5\), he first defined a covariant \(i=(ab)^4a_zb_z\) and the invariant A was then given by the symbolic relation \(A=(ii')^2\).

Here, x is the new unknown, the starting one being implicitly contained in the variables of the covariants \(\alpha \) and \(\delta \).

“Bekanntlich beruht Hermite’s Auflösung der Gleichungen 5ten Grades auf einer Lösung der Gleichung (14) mit Hülfe der elliptischen Functionen. Sobald die Invariante C einer Gleichung 5ten Grades verschwindet, ist durch das Vorige die Züruckführung der Gleichung auf diese Form, also ihre Lösung im Hermite’schen Sinne. Ist bei der gegebenen Gleichung aber C von Null verschieden, so kann man die Aufgabe, die Gleichung 5ten Grades zu lösen, darin setzen: dass mittelst einer höheren Transformation die Gleichung in eine solche mit verschwindendem C verwandelt werden soll. Aber in unserer geometrischen Interpretation heisst dies nichts anderes, als dass irgend eine Tangente der Curve \(C=0\) gefunden werden soll.” Clebsch’s emphasis.

In the process Clebsch proved many intermediate results, as well as a large number of properties that he did not exploit for his geometrical interpretation of the quintic.

At that time, Cayley would rather talk about the “deficiency” of a curve. See Dieudonné (1974), Gray (1989) and Houzel (2002). Moreover, let us recall that a different notion of genus existed, coming from the theory of algebraic forms as exposed in Gauss’ Disquisitiones Arithmeticae. On this point, see Lemmermeyer (2007).

A rational map is a map defined almost everywhere and rationally transforming coordinates; a birational map is an invertible rational map of which the inverse is also rational.

See Lê (2013, 59–60) for deeper explanations on Clebsch’s results and proofs.

The existence of 27 lines on every smooth, complex cubic surface had been stated and proved by Cayley and Salmon Cayley (1849) and Salmon (1849). See Lê (2015b) for elements of a history of the twenty-seven lines theorem, and especially its role in the encounters of groups, algebraic equations, and geometry in the second half of the nineteenth century.

A curve of order 6 with 6 double points is a curve of genus \((6-1)(6-2)/2-6=4\), which is equal to the genus of \(C=0\). However, it must be underlined that the equality of the genera of two curves does not imply the birational equivalence of the curves (whereas the reciprocal is true). Clebsch proved this birational equivalence by an approach which could be nowadays qualified as a computation of dimensions of spaces of curves.

A paragraph of the paper Clebsch (1866) in which Clebsch had established the existence of plane representations of cubic surfaces is devoted to such space curves.

“[Man bildet] diese Fläche 2ter Ordnung sodann von einem ihrer Punkte (dessen Auffindung nur die Lösung einer quadratischen Gleichung fordert) auf die gewöhnliche Weise ab” (Clebsch 1871b, 327).

“Jedem dieser Punkte endlich entspricht eine Tangente von \(C=0\)” (Clebsch 1871b, 327).

Such “splitting” equations are part of a bigger family, that of “geometrical equations,” which are algebraic equations associated to the determination of diverse geometrical configurations. For Clebsch and other mathematicians, these equations were part of an intuitive, geometrical understanding of the theory of substitutions, especially during the period 1868–1872 (Lê 2015a). See also Lê (2016), where the special organization of the activities involving geometrical equations is characterized as a cultural system.

“Auch diese Jerrard’sche Modification der Tschirnhausen’schen Methode ist, wenngleich nicht so direct wie die quadratische Substitution, einer Art geometrischer Deutung fähig” (Clebsch 1871b, 328).

For that purpose, remember that a line \(u_1z_1+u_2z_2+u_3z_3=0\) contains two points \((x_1:x_2:x_3)\) and \((y_1:y_2:y_3)\) if and only if \((u_1:u_2:u_3)=(x_2y_3-x_3y_2:x_3y_1-x_1y_3:x_1y_2-x_2y_1)\). Let us underscore that Clebsch did not make explicit any of the formulas of the representation.

“Wenn man nach Hermite die Gleichung \(x^5-ax-b=0 \quad (1)\) als durch elliptischen Functionen unmittelbar gelöst betrachtet, so kommt es nur darauf an, die Gleichung 5ten Grades in diese Form zu bringen. Man hat dann nur einen belibiegen Punkt der Raumcurve 6ter Ordnung zu ermitteln, was geschieht, indem man eine Erzeugende der Fläche \(\varPsi =0\) mit der Diagonalfläche schneidet. Dazu ist eine quadratische und eine cubische Gleichung zu lösen; erstere, um eine Erzeugende der Fläche 2ter Ordung zu finden; die andere, um die Durchschnitte derselben mit der Diagonalfläche zu bestimmen. Der gefundene Punkt der Raumcurve 6ter Ordnung giebt eine Tangente von \(C=0\), und wie das Schnittpunktsystem auf dieser zu der Form (1) führt, ist in §11. gezeigt worden. Kennt man die Schnittpunkte dieses Systems, so sind auch die Seiten des Fünfseits getrennt, die gegebene Gleichung 5ten Grades gelöst.”

In 1851, James Joseph Syvester had asserted that every cubic form \(F(x,y,z,w)=0\) can be brought to the form \(F=a_1z_1^3+a_2z_2^3+a_3z_3^3+a_4z_4^3+a_5z_5^3\) where \(z_1,\ldots ,z_5\) are linear forms in x, y, z, w satisfying the condition \(z_1+z_2+z_3+z_4+z_5=0\). The pentahedron of the cubic surface defined by \(F=0\) is the set of the five planes respectively defined by \(z_i=0\).

For instance, he proved that on the face \(\xi _5=0\), the equations of the diagonals are of the type

$$\begin{aligned} \left\{ \begin{array}{l} \xi _1+\xi _2 =0\\ \xi _3+\xi _4=0 \\ \xi _5=0. \end{array}\right. \end{aligned}$$It is then easy to check that each quintuplet \((\xi _1,\ldots ,\xi _5)\) satisfying these conditions also satisfies the equation \(\xi _1^3+\cdots +\xi _5^3=0\) of the surface.

“Ich werde diese specielle Fläche deswegen die Diagonalfläche des Pentaeders nennen” (Clebsch 1871b, 333). Afterward, Clebsch shortened the name and wrote “die Diagonalfläche.”

“Man sieht, dass auf dieser Fläche sofort 15 der 27 Geraden bekannt sind” (Clebsch 1871b, p. 333).

To check this point, remark that the line joining \((\omega ^{\alpha _1},\ldots ,\omega ^{\alpha _5})\) and \((\omega ^{-\alpha _1},\ldots ,\omega ^{-\alpha _5})\) is parameterized by \((\chi ,\lambda )\mapsto (\chi \omega ^{\alpha _1}+\lambda \omega ^{-\alpha _1},\ldots ,\chi \omega ^{\alpha _5}+\lambda \omega ^{-\alpha _5})\). A simple computation proves that these coordinates satisfy the equation \(\sum \xi _i^3=0\).

“Die Lösung der Gleichung 27ten Grades, von welcher die 27 Geraden der Fläche abhängen, erfordet bei der Diagonalfläche nur die Lösung der beim Pentaeder auftretenden Gleichung 5ten Grades und die Bestimmung von fünften Wurzeln der Einheit.”

A double-six is a set of twelve lines among the 27 contained in a cubic surface, satisfying particular incidence relations. In his paper on the plane representation of cubic surfaces, Clebsch had proven that the lines corresponding to the six fundamental points build half of a double-six.

“Für die wirkliche Darstellung des Systems der 27 Geraden einer Oberfläche dritter Ordnung, welche ein sehr verwickeltes System bilden, giebt die Diagonalfläche ein einfaches und leicht construirbares Beispiel, welche zugleich die grösste Zahl der Eigenschaften des allgemeines Systems ohne zu grosse Modificationen aufweist. Es dürfte sich daher zu Herstellung bequemer Modelle diese Fläche besonders empfehlen.”

In tangential coordinates \((u_1:u_2:u_3)\), the linear equation \(z_1u_1+z_2u_2+z_3u_3=0\) represents the point of punctual coordinates \((z_1:z_2:z_3)\).

Once again, this result had already been proven in Clebsch (1866).

“So finden sich denn wirklich alle Elemente der Auflösung der Gleichungen 5ten Grades hier in einem geometrischen Bilde zusammengefasst und verbunden” (Clebsch 1871b, 345).

Groups of transformations are not to be found in Clebsch’s article either. More generally, there are neither groups of substitutions, nor groups transformations in all the publications and manuscripts of Clebsch that I have read. In fact, some passages of his correspondence indicate that Clebsch had difficulties understanding these objects. See Lê (2016).

The effects of this prism on the reception of Galois’ works themselves have been thoroughly analyzed in Ehrhardt (2012).

For the mentions of the diagonal surface, see Klein (1884, 166, 218, 226). Moreover, let us note that the article of Clebsch is cited as an inspirational source in Klein (1871). In this paper, which is cited in the Vorlesungen über das Ikosaeder, Klein expressed for the first time the general idea of representing roots of an equation and their substitutions by points of space and associated linear transformations.

The conclusions of this paragraph and the preceding one match with the fate of Hermite’s research analyzed in Goldstein (2011).

These words come from the obituary of Hesse written by M. Noether: “Innerhalb zweier Jahre hat die deutsche algebraisch-geometrische Wissenschaft ihre beiden grössten Vertreter verloren: seinem so früh dahingeschiedenen Schüler Alfred Clebsch ist der Altmeister Otto Hesse jetzt nachgefolgt” (Noether 1875, 77).

References

Beauville, A. 2012. De combien de paramètres dépend l’équation générale de degré \(n\) ? Gazette des Mathématiciens 132: 5–15.

Bottazzini, U. 1994. Solving higher-degree equations. In Companion encyclopedia of the history and philosophy of the mathematical sciences, vol. 1, ed. I. Grattan-Guinness, 567–575. London: Routledge.

Brill, A., P. Gordan, F. Klein, J. Lüroth, A. Mayer, M. Noether, and K. von der Mühll. 1873. Rudolf Friedrich Alfred Clebsch - Versuch einer Darlegung und Würdigung seiner wissenschaftlichen Leistungen. Mathematische Annalen 7: 1–55.

Cayley, A. 1849. On the triple tangent planes of surfaces of third order. The Cambridge and Dublin Mathematical Journal 4: 118–132.

Clebsch, A. 1861. Ueber symbolische Darstellung algebraischer Formen. Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik 59: 1–62.

Clebsch, A. 1864. Ueber die Anwendung der Abelschen Functionen in der Geometrie. Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik 63: 189–243.

Clebsch, A. 1866. Die Geometrie auf den Flächen dritter Ordnung. Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik 65: 359–380.

Clebsch, A. 1871a. Bemerkungen zu der Theorie der Gleichungen \(5^{{\rm ten}}\) und \(6^{{\rm ten}}\) Grades. In Nachrichten von der Königlichen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften und der Georg-Augusts-Universität, 103–108

Clebsch, A. 1871b. Ueber die Anwendung der quadratischen Substitution auf die Gleichungen \(5^{{\rm ten}}\) Grades und die geometrische Theorie des ebenen Fünfseits. Mathematische Annalen 4: 284–345.

Clebsch, A. 1871c. Ueber die geometrische Interpretation der höheren Transformationen binärer Formen und der Formen 5ter Ordnung insbesondere. Nachrichten von der Königlichen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften und der Georg-Augusts-Universität 12: 335–345.

Clebsch, A. 1871d. Ueber die partiellen Differentialgleichungen, welchen die absoluten Invarianten binären Formen bei höheren Transformationen genügen. Abhandlungen der Königlichen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften in Göttingen 15: 65–99.

Clebsch, A. 1872. Theorie der binären algebraischen Formen. Leipzig: Teubner.

Clebsch, A. 1876. Vorlesungen über Geometrie. Leipzig: Teubner.

Clebsch, A., and P. Gordan. 1866. Theorie der Abelschen Functionen. Leipzig: Teubner.

Clebsch, A., and P. Gordan. 1867. Sulla rappresentazione tipica delle forme binarie. Annali di Matematica Pura ed Applicata 1: 23–79.

Dieudonné, J. 1974. Cours de géométrie algébrique, Voi. 1. Aperçu historique sur le développement de la géométrie algébrique. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Dugac, P. 1976. Richard Dedekind et les fondements des mathématiques. Paris: Vrin.

Ehrhardt, C. 2012. Itinéraires d’un texte mathématique: Les réélaborations des écrits d’Évariste Galois au \({\rm XIX}^{{\rm e}}\) siècle. Paris: Hermann.

Fischer, G. 1986. Mathematische Modelle. Braunschweig & Wiesbaden: Vieweg & Sohn.

Fisher, C.S. 1966. The death of a mathematical theory: A study in the sociology of knowledge. Archive for History of Exact Sciences 3(2): 137–159.

Flament, D. 2003. Histoire des nombres complexes. Entre algèbre et géométrie, Éditions du CNRS.

Gauthier, S. 2009. La géométrie dans la géométrie des nombres : histoire de discipline ou histoire de pratiques à partir des exemples de minkowski, mordell et davenport. Revue d’histoire des mathématiques 15: 183–230.

Giaquinto, M. 2007. Visual Thinking in mathematics: An epistemological study. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Giardino, V., and S. De Toffoli. 2013. Forms and roles of diagrams in knot theory. Erkenntnis 74(4): 829–842.

Goldstein, C. 2011. Charles Hermite’s Stroll through the Galois Field. Revue d’histoire des mathématiques 17: 211–270.

Gordan, P. 1870. Ueber die Invarianten binären Formen bei höheren Transformationen. Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik 71: 164–194.

Gray, J. 1989. Algebraic geometry in the late nineteenth century. In The history of modern mathematics, vol. 1. ideas and their reception, ed. J. McCleary, and D.E. Rowe, 361–385. London: Academic Press.

Gray, J. 2000. Linear differential equations and group theory from Riemann to Poincaré, 2nd ed. Basel: Birkhäuser. (First edition 1986).

Hermite, C. 1858a. Sur la résolution de l’équation du cinquième degré. Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des sciences 46: 508–515.

Hermite, C. 1858b. Sur quelques théorèmes d’algèbre et la résolution de l’équation du quatrième degré. Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des sciences 46: 961–967.

Hermite, C. 1865–1866. Sur l’équation du cinquième degré. Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Sciences 61–62:877–882, 965–972, 1073–1081, 65–72, 157–162, 245–252, 715–722, 919–924, 959–966, 1054–1059, 1161–1167, 1213–1215

Houzel, C. 2002. La Géométrie algébrique: Recherches historiques. Paris: Albert Blanchard.

Kiernan, B.M. 1971. The Development of Galois Theory from Lagrange to Artin. Archive for History of Exact Sciences 8: 40–154.

Klein, F. 1871. Ueber eine geometrische Repräsentation der Resolventen algebraischer Gleichungen. Mathematische Annalen 4: 346–358.

Klein, F. 1884. Vorlesungen über das Ikosaeder und die Auflösung der Gleichungen vom fünften Grade. Leipzig: Teubner.

Kronecker, L. 1858. Sur la résolution de l’équation du cinquième degré; extrait d’une lettre adressée à m. hermite. Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des sciences 46: 1150–1152.

Kung, J.P.S., and G.C. Rota. 1984. The invariant theory of binary forms. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 10(1): 27–85.

Lê, F. 2013. Entre géométrie et théorie des substitutions : une étude de cas autour des vingt-sept droites d’une surface cubique. Confluentes Mathematici 5(1): 23–71.

Lê, F. 2015a. “Geometrical Equations”: Forgotten Premises of Fleix Klein’s Erlanger Programm. Historia Mathematica 42(3): 315–342.

Lê, F. 2015b. Vingt-sept droites sur une surface cubique : rencontres entre groupes, équations et géométrie dans la deuxième moitié du \({\rm XIX}^{{\rm e}}\) siècle. Ph.D. thesis, Université Pierre et Marie Curie (Paris).

Lê, F. 2016. Reflections on the notion of culture in the history of mathematics: The example of “Geometrical Equations” Science in Context (to appear).

Lemmermeyer, F. 2007. The development of the principal genus theorem. In The shaping of arithmetic after C.F. Gauss’s disquisitiones arithmeticae, ed. C. Goldstein, N. Schappacher, and J. Schwermer, 527–561. Berlin: Springer.

Lorenat, J. 2015. Figures Real, Imagined, and Missing in Poncelet, Plücker, and Gergonne. Historia Mathematica 42: 155–192. doi:10.1016/j.hm.2014.06.005.

Lorey, W. 1937. Die Mathematik an der Universität Gießen vom Beginn des 19. Jahrhunderts bis 1914. Nachrichten der Giessener Hochschulgesellschaft 11(2): 54–97.

Neumann, C. 1872. Zum Andenken an Rudolf Friedrich Alfred Clebsch. In Nachrichten von der Königlichen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften und der Georg-Augusts-Universität, 550–559

Noether, M. 1875. Otto Hesse. Zeitschrift für Mathematik und Physik: Historisch-literarische Abtheilung 20: 77–88.

Parshall, K.H. 1989. Toward a history of nineteenth-century invariant theory. In The history of modern mathematics, vol. 1. ideas and their reception, ed. J. McCleary, and D.E. Rowe, 157–206. London: Academic Press.

Petri, B., and N. Schappacher. 2004. From Abel to Kronecker. Episodes from 19th Century Algebra. In The Legacy of Niels Henrick Abel, ed. O.A. Laudal, and R. Piene, 227–266. Berlin: Springer.

Polo-Blanco, I. 2007. Theory and history of geometric models.

Rowe, D.E. 1989. Klein, Hilbert, and the Göttingen Mathematical Tradition. Osiris 5(2): 186–213.

Rowe, D.E. 2013. Mathematical Models as Artefacts for Research: Felix Klein and the Case of Kummer Surfaces. Mathematische Semesterberichte 60: 1–24.

Salmon, G. 1849. On the triple tangent planes to a surface of the third order. The Cambridge and Dublin Mathematical Journal 4: 252–260.

Shafarevich, I. 1983. Zum 150. Geburtstag von Alfred Clebsch. Mathematische Annalen 266: 133–140.

Tournès, D. 2012. Diagrams in the theory of differential equations (eighteenth to nineteenth centuries). Synthese 186: 257–288.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Catherine Goldstein for her precious comments. I would also like to warmly thank Jeremy Gray for his remarks on the paper and his linguistic help.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by: Jeremy Gray.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lê, F. Alfred Clebsch’s “Geometrical Clothing” of the theory of the quintic equation. Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 71, 39–70 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00407-016-0180-5

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00407-016-0180-5