Abstract

Neurodegenerative disorders especially Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are significantly threatening the public health. Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors are compounds of great interest which can be used as effective agents for the symptomatic treatment of AD. Although plants are considered the largest source for these types of inhibitors, the microbial production of AChE inhibitors represents an efficient, easily manipulated, eco-friendly, cost-effective, and alternative approach. This review highlights the recent advances on the microbial production of AChE inhibitors and summarizes all the previously reported successful studies on isolation, screening, extraction, and detecting methodologies of AChE inhibitors from the microbial fermentation, from the earliest trials to the most promising anti-AD drug, huperzine A (HupA). In addition, improvement strategies for maximizing the industrial production of AChE inhibitors by microbes will be discussed. Finally, the promising applications of nano-material-based drug delivery systems for natural AChE inhibitor (HupA) will also be summarized.

Key Points

• AChE inhibitors are potential therapies for Alzheimer’s disease.

• Microorganisms as alternate sources for prospective production of such inhibitors.

• Research advances on extraction, detection, and strategies for production improvement.

• Nanotechnology-based approaches for an effective drug delivery for Alzheimer’s disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors are chemical compounds which considered being among the most therapeutic tools for many neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), glaucoma, Parkinson’s disease, myasthenia gravies, and Down syndrome. AChE inhibitors belong to many classes such as carbamate derivatives which participate in the action mechanism of insecticidal drugs, while those belonging to parathion and malathion play a significant role in nerve gases (Erdogan Orhan et al. 2011).

AD is a serious neurodegenerative disease, mostly targeting people above 65 years of age (Mohamed and Rao 2011). AD patients are suffering mainly from sequential memory loss and deficiency of their cognitive functions (Khairallah and Kassem 2011). AD threatens the public health and society as the epidemiological data indicated that the number of people affected with AD worldwide by 2050 is expected to increase, predicting that, every 33 s, there will be one new AD case (Prince et al. 2013; Alzheimer’s Association 2017).

About 5% of the people above 65 years and more than 20% above 80 years are subjected to the risk of AD. After cardiovascular diseases and cancer, AD is considered to be the third main reason of death in the developing countries. Pathogenesis of AD is complex and includes genetic and environmental factors (Williams et al. 2011).

This disorder is characterized by the progressive irreversible loss of neurons in specific brain areas, mainly the hippocampus, accumulation of β-amyloid protein (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) in brain tissues, hyper-phosphorylation of Tau protein in neurons, and collapsing of cognitive functions leading to death (Khairallah and Kassem 2011; Mohamed and Rao 2011).

Surprisingly, oxidative stress and the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) are considered to be the main causes of this disease (Behl and Moosmann 2002). As AD is a multi-factorial disease, many therapeutic approaches were suggested for its treatment. Therapeutic approaches were then classified into two main effective routes, cholinergic and non-cholinergic. In patients with AD, the disorder in the cholinergic neurotransmission is causing a decline in the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) (Konrath et al. 2013).

As a result, acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors could rebalance the level of acetylcholine by inhibiting the AChE activity. Consequently, acetylcholine could be accumulated in the synaptic cleft (Su et al. 2017). This route is called cholinergic approach and considered as the major symptomatic treatment for AD.

Another treatment approach depends on preventing the accumulation of β-amyloid peptide (Aβ). Thus, any compound, able to reduce or prevent the aggregation of Aβ between neurons, could be a potential anti-AD drug candidate which can reduce the disease progression (Jiang et al. 2003). Other suggested approaches included many compounds and routes such as antioxidants, vitamins, anti-hypertensive drugs, selective phosphodiesterase inhibitors, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, transition metal chelators, inhibitory drugs of Tau proteins hyper-phosphorylation and intracellular NFT accumulation, use of brain-derived neurotropic factor (BDNF), stem cell therapy, and hormonal therapy (Dey et al. 2017). Additionally, stimulatory therapies such as physical exercise, cognitive training, socialization, and music have been reported. Moreover, nutritional supplements, medicinal plants, phyto-chemicals, minerals, and omega-3 fatty acids have been also tested (Wollen 2010).

AChE inhibitors can be obtained either by chemical synthesis or by extraction from natural plants and microorganisms. Microbial production of AChE inhibitors is gaining a lot of attention due to its advantages over both phyto-extraction and chemical synthesis. On the one hand, extraction processes are limited by lacking of natural plant resources due to their excessive harvesting, and chemical synthesis is threatening the environment by pollution and hazardous materials (Wang et al. 2015b).

On the other hand, marked-available AChE inhibitors derived from plants and chemical synthesis showed many disadvantages such as low bioavailability and other abdominal side effects (Erdogan Orhan et al. 2011). Thus, exploring other alternatives of AChE inhibitors derived from microbial sources with different niches is a must.

Huperzine A (HupA) is a Lycopodium alkaloid, which can be naturally extracted from the traditional Chinese medicinal plant, Huperzia serrata. HupA has attracted intense attention after discovering its activity as an effective cholinesterase inhibitor (Ishiuchi et al. 2013). Compared with the well-known and commercially available AChE inhibitors, HupA is a more effective reversible inhibitor.

Additionally, it can effectively penetrate the blood–brain barrier and showed better oral bioavailability and longer inhibitory effect (Wang et al. 2006). Consequently, since 1996, HupA appeared in the Chinese drug market in a form of tablets named Shuangyiping for symptomatic treatment of AD, while in the USA and Europe, HupA is present as a dietary supplement (H. serrata powder in a capsule format) for limiting further memory disorders (Ma and Gang 2008).

This review collects a variety of soil, marine, and endophytic microorganisms which considered promising producers of anti-AD drugs that showed in vitro anti-AChE activity. In addition, it summarizes recent reports on the production, extraction, and detection methodologies of the most effective anti-AD drug candidate HupA with the established and recommended enhancement strategies for scaling up the microbial production of AChE inhibitors, to open the way towards the large-scale production. Moreover, incorporation of these active compounds with nano-structured drug delivery systems to increase their selectivity and reactivity will be also discussed.

Acetylcholinesterase and AChE inhibitors

The enzyme acetylcholinesterase selectively catalyzes the ester bond in acetylcholine via hydrolysis at the synaptic cleft to stop its impulse transmitting role. Accordingly, the activated cholinergic neurons return to the resting state (Williams et al. 2011). In addition, AChE regulates the cholinergic neurotransmission in vertebrates by inactivating acetylcholine immediately after presynaptic neurons releasing (Pope and Brimijoin 2018).

AChE inhibitors began to be very attractive to be used in AD symptomatic therapy, after the initial discovery of physostigmine, a Physostigma venenosum Balf (Fabaceae) seed-derived alkaloid, which can reverse scopolamine inducing cognition disruption in animal models. Although physostigmine shows a quick, selective, and reversible AChE inhibitory effect, its current use is limited by many limitations such as its gastrointestinal effects, short half-life, and narrow therapeutic image (Konrath et al. 2013).

AChE inhibitors could not only improve the cholinergic transmission but also they showed a protective role against free radical injury of brain cells and interfere against aggregation and deposition of amyloid beta protein as the second suggested mechanism of AD (Almasi et al. 2018). Because of the medicinal value of these inhibitors, there is a massive research interest focusing on the development of new AChE inhibitors.

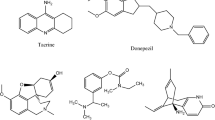

The approved AChE inhibitors for treating AD

Many drugs have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for symptomatic treatment of AD patients. Most of these drugs are AChE inhibitors. For example, Tacrine was approved in 1993, but it was withdrawn from market in 2012 because of its hepato-toxicity which affected more than 29% of patients. In addition, Donepezil was approved in 1996 as a reversible AChE inhibitor and a fully synthetic compound with good inhibitory effect and low toxic effects than Tacrine. Moreover, galantamine was approved in 2001 as a natural alkaloid extracted from Galanthus nivalis L. and related plants in Amaryllidaceae family (Heinrich and Teoh 2004; Marco and Carreiras 2006). More and above, Rivastigmine which is a semi-synthetic derivative of physostigmine, was approved in 2000. Although it did not show liver toxicity like Tacrine, it showed other side effects such as nausea and vomiting (Zhao et al. 2004).

Microbial production of AChE inhibitors

Plants represent the main significant source of AChE inhibitors. However, few researches reported the ability of some microorganisms to produce similar inhibitors (Pandey et al. 2014). Searching for natural, cost-effective, and sustainable source of effective AChE inhibitors became an attractive scope for many researchers. Hence, great efforts have been dedicated for investigating the production of AChE inhibitors by microbial strains isolated from soil and marine environments, and unusual sources such as plant-associated microbes known as endophytes (Singh et al. 2012). Table 1 summarizes most-recent reported data on the microbial anti-AChE activity and the identified microbial AChE inhibitors by various microorganisms from different niches.

Endophytic fungi as new sources for AChE inhibitors

Endophytic fungi are mutualistic microorganisms, occupy the internal tissues of healthy plants through certain life stages or throughout their whole life, without leading to any significant disease symptoms on the host (Strobel 2003; Ismaiel et al. 2017). They are known to provide a plethora of fitness benefits to the host as previously reported endophytes are biologically active and can efficiently enhance the growth of their host, and promote host resistance to diseases-causing phyto-pathogens and environmental stress (Aly et al. 2011).

Interestingly, they can also produce identical or similar bioactive substances as host plants (Strobel 2003). After Stierle et al. (1993) reported the discovery of an endophytic fungus, Taxomyces andreanae, which can produce the anticancer-active substance, paclitaxel, the endophytic fungi producing pharmaceutically active compounds have gained significant consideration worldwide.

The hypothesis of horizontal gene transfer has revealed the capability of endophytes to produce the same active compounds which produced by host plants. Moreover, they could produce some novel medicines against some incurable diseases (Strobel 2003; Strobe and Daisy 2003; Staniek et al. 2008). However, the unmanaged harvesting of plant resources for extracting AChE inhibitors would lead to their depletion. For protecting these resources, the capability of producing similar AChE inhibitors by endophytes of medicinal plants has been widely investigated. Endophytic fungi proved their efficiency as valuable, novel, and alternate resources with good AChE inhibitory activity (Wang et al. 2015b; Ali et al. 2016).

Endophytic fungi with good anti-AChE activity are presented in Table 1. Recovery of endophytic fungi from healthy plant tissues led to a massive argument whether these entophytes are plant pathogen or not. According to Chen et al. (2010) and Mohinudeen et al. (2019), endophytic fungi may appear at two phases, non-pathogenic and pathogenic. Many non-pathogenic endophytes are dormant pathogens and may become pathogenic under certain environmental stress conditions or after plant aging. Other possible reason may be attributed to the nature of host species as endophytes can be useful and growth stimulating to certain host species while they can be pathogenic to other plants.

HupA identity and structural elucidation

Huperzine A is a naturally occurring sesquiterpene alkaloid compound found in the extract of the Chinese club moss botanically known as Huperzia serrata (also known as Lycopodium serratum). It can be also found with varying quantities in other Huperzia species, including H. elmeri, H. carinat, and H. aqualupian (Lim et al. 2010). H. serrata grow at high alleviations and in cold climates. It has been used for centuries in the Chinese Folk Medicine (known as Qian Ceng Ta). The chemical stability of HupA is very good, and it possesses good resistant to structural changes in both acidic and alkaline solutions, which indicated that HupA has a relatively longer shelf life. The chemical structure of HupA is displayed in Fig. 1.

HupA has been extensively investigated as a treatment for neurological conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease; a meta-analysis concluded that previous studies were of poor methodological quality and the findings should be interpreted with caution (Yang et al. 2013). HupA inhibits the breakdown of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine by acetylcholinesterase enzyme, and this is the same mechanism of action of AD-treating pharmaceutical drugs such as galantamine and donepezil. HupA is commonly available over the counter as a nutrient supplement, and was marketed as a cognitive enhancer for improving memory and concentration (Ma X, Gang DR 2008).

HupA [IUPAC name: (1R,9S,13E)-1-amino-13-ethylidene-11-methyl-6-azatricyclo-[7.3.1.02,7]-trideca-2(7),3,10-trien-5-one; commercially known as CogniUp] is an alkaloid, an AChE inhibitor, and N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (and glutamate receptor) antagonist (Table 2; (Wang et al. 2008).

The acute oral toxicity (LD50) of HupA was found to be 4.6 mg/kg body weight in mice. Considering a therapeutic oral dose of 0.2 mg HupA/kg body weight, it shows a wide margin of safety (Bagchi and Barilla 1998). Extensive laboratory testing of HupA has been performed, demonstrating its non-mutagenic properties as revealed by Ames’ bacterial reverse mutation assay (Li et al. 2012).

Biosynthesis of HupA: related genes and enzymes

Distribution of gene functions and biochemical pathways in Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (HupA-producing fungus) was based on the Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) assignments, particularly in the categories of molecular function and metabolism (Zhang et al. 2015b). These annotations provide valuable resources for the investigation of gene functions, and cellular structures and processes in C. gloeosporioides.

Among the 308 metabolic pathways (annotated by KEGG), three pathways were involved in alkaloid biosynthesis: lysine biosynthesis, biotin metabolism, and (tropane, piperidine, and pyridine) alkaloid biosynthesis. A total of 30 unigenes in this library showed similarities to the non-characterized enzymes that might be associated with the biosynthesis of HupA (Table 3).

Based on these three pathways and more literature survey (Luo et al. 2010; Choi et al. 2012; Liu et al. 2012), a more detailed biosynthetic pathway was deduced as shown in Fig. 2 with related enzymes and genes as shown in Table 3. The discovery of new transcripts will further facilitate the elucidation of the biosynthetic mechanisms of HupA at the molecular level in C. gloeosporioides (Zhang et al. 2015a, b, c, d).

HupA production and supply problems

There is a serious problem obstructing the large-scale production of this highly effective drug as Huperziaceae plant species specially, Huperzia serrata which are the major source of HupA, give low extracted yield and their vegetative cycle is very long (Ma and Gang 2008). It means that these plants are not considered to be effective source for HupA production at the commercial scale. As a result, researchers tried to find other methods to produce HupA such as in vitro plant tissue cultivation and chemical synthesis. Tissue culturing was not considered as a successful technique for HupA production at a large scale (Ma and Gang 2008; Ishiuchi et al. 2013). Although HupA was totally synthesized from (R)-pulegone (Ding et al. 2012), the chemical synthesis of HupA showed some limitations such as complex interactions, continual pollution, and expensive processes (Koshiba et al. 2009). As these trials have not achieved satisfactory results to be applied at a large industrial scale, the discovery of HupA-producing endophytic fungi from the tissues of Huperziaceae plant species provides an alternative solution.

Although the production of HupA drug from endophytes would reduce the price of traditional drugs and effectively protect the ecological environment, only a small number of endophytic fungi that produce HupA were reported. Li et al. (2007) reported the recovery of HupA-producing endophytic fungal species from tissues of Huperzia serrata. This finding stimulated many researchers to isolate and screen many endophytic fungi from Huperzia serrata and other related plants such as Phlegmariurus, and this research interest is still increasing till today. The reported HupA-producing endophytes with varying HupA yield are highlighted in Table 4.

Isolation of endophytic fungi from Huperziaceae plant species

Since, endophytic fungi were suggested as prospective sources for HupA production, isolation of endophytic fungi from stems, leaves, and roots of healthy Huperziaceae species was the first serious challenge. The main principle of endophytic fungal isolation involved the recovery of fungal species at the internal plant tissues which was successfully achieved through surface sterilization of the tested plant samples.

Surface sterilizing sequence differed from report to another as demonstrated in Table 5. Ju et al. (2009) used 70% ethanol for seconds, 0.2% mercuric chloride (HgCl2) for 1 min, 2% sodium hypochlorite, then rinsing in distilled water, while 75% ethanol for 2 min, 0.1% HgCl2 for 8 min, then successive rinsing in sterile water were reported (Wang et al. 2011a; Zhang et al. 2015a).

Additionally, 75% ethanol for 5 min and 0.1% HgCl2 for 8 min were reported (Zhu et al. 2010). Another report used 75% ethanol for 2 min and 0.1% HgCl2 up to 10 min (Wang et al. 2011b). Similarly with slight difference, 75% ethanol for 5 min and 0.2% HgCl2 for 1.5 min were used (Shu et al. 2014). Differently, 0.1% HgCl2 for 15 min was used to disinfect the stems while, 0.1% HgCl2 for 10 min was used for leaves and roots (Dong et al. 2014).

Additionally, 75% ethanol for 30 s, 10% sodium hypochlorite for 5 min, and 75% ethanol for 30 s again were reported (Han et al. 2015). Similarly, 75% ethanol for 1 min, 3.4% sodium hypochlorite for 10 min, and 75% ethanol for 30 s again were also reported (Cruz-Miranda et al. 2019). Finally, ethanol (70%) for 1 min and 1% available chlorine for 3 min were also investigated (Zaki et al. 2019). After surface tissue sterilization, the plant parts were cut into small segments and directly cultured on a suitable media; potato dextrose agar (PDA) was mostly chosen, which was enriched by streptomycin, 60 μg/ml, and ampicillin, 100 μg/ml, to avoid bacterial contamination (Zhu et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2011a, b; Zhang et al. 2015a; Zaki et al. 2019; Cruz-Miranda et al. 2019). Shu et al. (2014) and Dong et al. (2014) used Murashige and Skoog (MS) media for endophytes’ isolation. Indeed, more than one type of media can be used to encourage the emergence of more endophytic strains by using both PDA and MS media as reported by Ju et al. (2009).

HupA extraction and detection from endophytic fungal culture

HupA is an intracellular metabolite of endophytic fungi and is mainly extracted from the fungal biomass. Thus, the HupA extraction method depends primarily on some sequenced steps of biomass grinding, acidic soaking, and ultrasonication in order to weaken the fungal cell walls and facilitate the extraction of the targeted intracellular metabolite (Pinu et al. 2017).

As HupA is an alkaloid compound by nature, it could be extracted by the conventional acid-water method. However, Weigang et al. (2013) and Ting et al. (2015) studied the significant extraction factors and determined the optimum levels for maximizing the HupA extracted yield from H. serrata using Box-Behnken factorial design. Currently, there are no reported extraction optimization studies for maximizing the extraction of HupA from fungal biomass and the different extraction conditions have been reported and summarized in Table 5.

Ju et al. (2009) used 2% tartaric acid on the fungal dried biomass followed by ultrasonic extraction for 2 h. Then, high-speed centrifugation at 10.000 rpm for 10 min; finally, supernatant was screened for HupA. Wang et al. (2011a) and Dong et al. (2014) exposed the collected cells to sonication with immersion in 95% ethanol overnight, then the extract was concentrated under reduced pressure.

Other reports soaked the dried cells (1 g) overnight in 50 mL of 0.5–1.5% (v/v) hydrochloric acid (Zhao et al. 2013; Shu et al. 2014;Han et al. 2015; Zaki et al. 2019) or 2% tartaric acid (Zhang et al. 2015a), then cells were disrupted by ultrasonication for 40 min. After that, ammonia solution was used to alkalize the water phase (pH 9); thus, alkaloids containing HupA left the water phase and transferred to the chloroform layer upon vigorous shaking.

After that, the chloroform extract was evaporated, and the obtained residue was dissolved in methanol. Zhu et al. (2010) and Cruz-Miranda et al. (2019) applied sequential extraction; the dried cells underwent extraction with 75% ethanol for 30 min in a 40 °C ultrasonic bath. Then, alcoholic extracts were allowed to evaporate under reduced pressure. After that, 2.5% hydrochloric acid was added to dissolve any dried residues. Then, ammonia solution was added followed by chloroform extraction and evaporation. Finally, the obtained dried residues were dissolved in 1 ml solvent (mostly methanol) for HupA identification.

HupA in an alkaloid extract from the endophytic fungi could be mainly identified and quantified by using spectroscopic and chromatographic analyses such as thin-layer chromatography (TLC), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and mass spectrometry (MS) analyses. Each analysis conditions and the composition of tested mobile phases were reviewed in Table 5 as the following: the preliminary identification step for HupA is application of TLC analysis, where the extracted HupA and standard samples were loaded on silica gel-coated plates with developing run reagent that differed from one report to another (Table 5), as it was composed of acetone: chloroform: isopropanol (4:4:2 v/v/v) (Wang et al. 2011a, b; Han et al. 2015), acetone: chloroform: isopropanol: ammonia (4:4:2:0.12) (Zhu et al. 2010; Zaki et al. 2019); acetone: chloroform: isopropanol: ammonia (4:4:1.5:0.15); acetic acid:1-Butanol:water (3:3:2); 1-Butanol: isopropanol: water (10:5:4); 1-Butanol: isopropanol: acetic acid: water (7:5:2:4); chloroform: acetone: methanol (65:35:5) (Zhu et al. 2010).

Then, HupA spot was visualized using UV-fluorescence at 254 nm (Su and Yang 2015) or by spraying 3% (w/v) potassium permanganate as a chromogenic reagent forming yellow spots containing HupA compound against a violet background (Zhu et al. 2010). HupA extracted from the positive producing strains recorded the closest migration rate to the standard HupA with a retention factor (RF) between 0.70 and 0.73 (Zhu et al. 2010).

Subsequent characterization and quantification of HupA were performed using different HPLC methodologies as shown in Table 5. The extracted HupA content can be quantified using a standard curve that was created by analyzing the concentration range of HupA standard sample, and represented by μg/g dcw (dried mycelia).

Li et al. (2007) used HPLC with a mobile phase of acetonitrile: 0.02 M KH2P04 (10:90), flow rate 1 ml/min, 20 μl injected sample, column temperature (25 °C), and detecting wavelength of 310 nm, while HPLC mobile phase of methanol: 0.8% ammonium acetate solution (33: 67, p H 6.0), flow rate: 1 ml/min, column temperature: 25 °C, detection wavelength: 310 nm, and the injection volume: 20 μL was reported by Ju et al. (2009).

Additionally, Zhou et al. (2009) used a run solvent of 10% acetonitrile, 35 °C column temperature, and 308 nm detecting wavelength. Other reports (Zhu et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2011a; Zaki et al. 2019) performed HPLC with a mobile phase of methanol: water (85: 15), 1.0 mL/min as flow rate, 25 °C column temperature, 10 μL injected volume, and 310 nm detecting wavelength.

Also, a mobile phase composed of ammonium acetate (80 mM, or 0.1 M, pH 6.0): methanol (7: 3 or 6: 4 or 36: 64 v/v) was also tested (Zhao et al. 2013; Dong et al. 2014; Su and Yang 2015). In addition, Han et al. (2015) applied a mobile phase of methanol: 0.1% formic acid (75: 25 v/v). Different mobile phases of acetonitrile: water (acidified with 0.0125% trifluoro-acetic acid) (15: 85 v/v) were also investigated (Cruz-Miranda et al. 2019).

Confirmatory analyses combining both liquid chromatography (LC) and mass analysis by mass spectrometry (MS) using LC/MS and UPLC/MS analyses were also performed, where the alkaloid extract underwent chromatographic separation using a suitable run solvent as methanoic acid (0.1%): acetonitrile (9: 1 v/v) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min (Su and Yang 2015), 10 mM ammonium acetate (pH 3.5) and methanol with 5: 56: 56% gradient elution (T: 0: 20: 30 min) (Shu et al. 2014), methanol: 0.2% aqueous formic acid (50: 50 v/v), flow rate of 0.15 mL/min, 308 nm as a detecting wavelength, and 5 μL injected volume (Zhang et al. 2015a), and acetonitrile: 0.025% formic acid 15: 85 v/v, 0.25 mL/ min as a flow rate (Cruz-Miranda et al. 2019), then the elute of the chromatography was subjected to MS analysis.

Improvement strategies for enhancing the production of microbial AChE inhibitors

Till now, there are no commercial products of AChE inhibitors depending on the microbial fermentation processes. Hence, enhancement of microbial strains for large-scale production through process optimization and irradiation-assisted strain improvement will lead to a cost-effective fermentation.

In any microbial fermentation process, optimization of process variables such as medium designing is considered to be one of the most important and critical scopes. The constituents of fermentation medium have a significant impact on microbial growth and productivity. Additionally, for the production of valuable compounds, medium components such as nitrogen, carbon, and phosphate sources have a large impact on the cost of overall process and the feasibility of product separation (Singh et al. 2017).

Moreover, chemical elicitors that enhance the production process can greatly affect the process cost. The ideal method for designing the optimum fermentation medium could be started by studying the optimum physical fermentation conditions and may end with optimizing medium components. There are few reports explaining the optimization of medium components and fermentation condition for maximizing HupA yield from endophytes (Li et al. 2007; Zhao et al. 2013; Fangfang et al. 2015).

Currently, multi-factorial statistical designs including response surface methodology could be used for the optimization of fermentation medium components. Recently, Zaki et al. (2019) used both Plackett–Burman and central composite models for optimizing the fermentation conditions and medium composition resulting in 40.8% enhancement of HupA production by the endophytic fungus Alternaria brassicae AGF041.

Related studies that employed factorial designs for optimizing the production of valuable microbial secondary metabolites were also reported. Abdel-Fattah et al. (2007) used this strategy for determining the optimum fermentation conditions required for maximum fungal cyclosporin A production. Additionally, Xu et al. (2006), Garyali et al. (2014), and El-Sayed et al. (2019d) applied response surface methodology for maximizing the production of the anticancer drug taxol by endophytic fungi.

Strain improvement through irradiation mutagenesis for hyper-production of industrial products is of critical importance as the improved mutants can show more desirable properties, and give relatively higher productivity with lower cost (Parekh et al. 2000).

Subjecting the microbial cells to radiation leads to physiological, chemical, and metabolic differences as radiation imposes an extra stress to cells disturbing their organization (Unluturk 2017). Microbial strain mutation can be achieved by exposing the microbial cells to chemical or physical agents (such as UV. and gamma-rays) which is called mutagens. As a result, the genetic materials of the subjected cells would be affected resulting in a strain modification. UV. radiation is a non-ionizing radiation of a moderate effect, and considered as a first choice mutagenic agent (Irum and Anjum 2012).

Irradiation of microbial cell by UV. rays results in pyrimidine dimerization and DNA cross linking (Parekh et al. 2000), while irradiation by the highly energetic ionizing radiation such as gamma-rays causes mutations through DNA breakage in the single or double strands, nucleotide deletion, or structural modification and cross linking in the DNA-protein (Cadet et al. 1999).

Xiao-qion et al. (2015) applied UV irradiation mutagenesis of protoplast of HupA-producing endophytic fungal strain NX9 resulting in 16.7 times production increase. In literature, UV. and gamma-rays were employed for improvement of fungal strains and overproduction of different pharmaceutical products such as mycophenolic acid by irradiated Penicillium roqueforti AG101 and LG109 strains (Ismaiel et al. 2014, 2015; El-Sayed et al. 2019c), paclitaxel by UV-irradiated Fusarium mairie (Xu et al. 2006), taxol by UV. and gamma-irradiated Aspergillus fumigates and Alternaria tenuissima (El-Sayed et al. 2019d), and the cardiac glycoside digoxin by gamma-irradiated Epicoccum nigrum (El-Sayed et al. 2019a).

Nanotechnology and AChE-inhibitor HupA drug delivery

Various nano-materials possess exceptional physical, chemical, and physiological characteristics allowing them to be perfect candidates for many applications (Maksoud et al. 2018, 2019; Pal et al. 2018; Thirugnanasambandan et al. 2018; Asiya et al. 2020; Elkodous et al. 2019c; Govindasamy et al. 2019; Pal et al. 2019; Jeevanandam et al. 2020). Biomedical applications of nano-materials have gained significant consideration from numerous researchers across the past decade because of the important role they can perform in improving the public health (Elkodous et al. 2019a, b, d, e; El-Batal et al. 2019; Wong et al. 2019; Abdelhakim et al. 2020; Elkhenany et al. 2020; El-Sayed et al. 2020a, b).

Nanotechnology advances through nano-material-based drug delivery systems have opened the way for better treatment of AD (Fonseca-Santos et al. 2015; Ansari et al. 2017; Wen et al. 2017). Designed nano-carriers can effectively cross the blood–brain barrier (Costantino et al. 2005; Mahajan et al. 2010; Guarnieri et al. 2014; Gao 2016). Thus, concentration of drugs in the target neural cells will be significantly increased with respect to the traditional methods of treatment without nano-carriers (Wen et al. 2017). This superior activity of nano-carriers can be attributed to their tiny size and their ability to be bounded with specific moieties for better selectivity and permeability (Peer et al. 2007;Arruebo et al. 2009;Tiwari et al. 2011).

HupA can be delivered effectively to the brain through many nano-carriers such as polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs), lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), liposomes, nano-emulsions, and micro-emulsions as presented in Fig. 3.

Polymeric nanoparticles

Polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) possess a lot of attractive characteristics allowing them to be well-suited for the delivery of HupA such as their biocompatibility, good stability, lower toxicity, controllable drug release, ease in production, and their lower immunogenic responses (Khalil and Mainardes 2009).

PNPs are colloidal NPs with higher surface area, and drugs can be linked to them through physical adsorption or by chemical bonds through surface modifications after grafting with other polymers such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) and poloxamers (Cismaru and Popa 2010; Elsabahy and Wooley 2012). However, the rapid clearance of PNPs from blood circulation as a result of their interaction with reticulo-endothelial system is a challenging issue that needs further investigation (Reis et al. 2006; Jawahar and Meyyanathan 2012).

Lipid nanoparticles

Unlike PNPs, LNPs are dispersions possessing the same advantages of PNPs with relatively smaller size and better control of drug release, targeting, and higher stability against drug degradation (Patel et al. 2013). LNPs comprise two main types: solid-lipid NPs (SLNPs) and nano-structured lipid carriers (NLCs) (Wissing et al. 2004; Naseri et al. 2015). The main difference between the two types is that SLNPs have lipid core which stay solid at body temperature while NLCs contain a mixture of solid and liquid lipids (Gastaldi et al. 2014).

SLNPs were developed in 1991 providing a promising drug delivery potential with respect to other colloidal vectors like PNPs, liposomes, and emulsions; they were particularly designed for the transfer of a lipophilic composite (Freitas and Müller 1999). The principal advantages of SLNPs are their higher selectivity, biocompatibility, absence of organic solvents during preparation, and improved drug release. However, they exhibited some restrictions such as fixed drug packing space and drug removal capacity throughout the storage process (poor drug loading efficiency) (Mukherjee et al. 2009). To overcome limitations of SLNPs, NLCs were developed and received considerable investigations (Müller et al. 2002). NLCs were extensively employed for HupA delivery due to their unique solid-liquid lipid matrix as displayed in Fig. 4.

NLCs are generated by mixing solid lipids with spatially inconsistent liquid lipids under controlled conditions which are directed to nanostructures with increased drug conjugation and discharge features (Souto et al. 2004). HupA-loaded NLCs were effectively synthesized by a tailored method of melt ultrasonication followed by high pressure homogenization (Yang et al. 2010).

The DSC results revealed that HupA matrix that overloaded with NLCs possessed poor crystal arrangement. As a result, a lot of imperfections can be generated leading to gaps hindering drug loading. In vitro study showed an early rupture followed by an extended release (Yang et al. 2010). In addition, Patel et al. (2013) performed in vitro and in vivo comparative study to test the delivery of HupA; they used micro-emulsion template method to prepare SLNPs, NLCs, and micro-emulsions for the treatment of AD. Their results showed the significant ability of micro-emulsions followed by SLNPs and then NLCs to deliver HupA after 24 h of treatment. Moreover, mice groups treated with these HupA-loaded nano-carriers showed significant developments in cognitive abilities with respect to the control group.

Recently, a complex of HupA-loaded muco-adhesive and polylactide-co-glycoside (PLGA-NPs) with external adjustment by lactoferrin-conjugated N-trimethylated chitosan (Lf-TMC NPs) was generated for effective intranasal distribution of HupA to the brain for potential Alzheimer’s disorder therapy (Sheng et al. 2015; Meng et al. 2018).

Unfortunately, NLCs have some limitations as the drug loading into them is controlled by many parameters such as lipid type, lipid character, production method, and surfactants used in production (Qian et al. 2013; Kathe et al. 2014; Lauterbach and Müller-Goymann 2015).

Liposomes

Liposomes are 50–100 μm spherical vesicles, composed of phospholipid-bilayer enclosing inner core (Wright and Huang 1989; Schroeder et al. 2009). They are highly biocompatible and non-toxic (He et al. 2019). In addition, they have the ability to encapsulate both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs and they exhibit superior protection ability of encapsulated drugs against enzymatic degradation (Bruch et al. 2019;Mirab et al. 2019). However, they showed phospholipid-type dependent stability; the charge of phospholipids affects their stability (Wen et al. 2017).

Nano-emulsion and micro-emulsions

Oil-in-water nano-emulsions are cloudy and surfactant-stabilized heterogeneous drug delivery systems; they are composed of oil droplets (10–100 nm) dispersed in water or other aqueous solutions (Hort et al. 2019; Karami et al. 2019). On the other hand, nano-emulsions can be effectively used to encapsulate HupA with high protection against degradation and can be produced at the large scale (Jiang et al. 2019). Jiang et al. (2019) reported a new nano-emulsion-based system loaded with Lactoferrin for enhanced targeted drug delivery via intranasal administration. Their results showed the successful targeting of hCMEC/D3 cells, and their system is non-toxic and was highly stable up to 6 months (Jiang et al. 2019).

However, nano-emulsions have some limitations such as instability phase separation and non-controlled release (Basha et al. 2019). On the other hand, micro-emulsions are clear and transparent systems composed of water, oil, and amphiphile which is a stable liquid solution (Poh et al. 2019). The advantages of micro-emulsions over nano-emulsions are their thermodynamic stability and cost-effectiveness as they do not need too much energy (Kumar and Pravallika 2019). But, micro-emulsions need large amounts of emulsifiers (Doering 2019).

All and above, the chemical structure of HupA (as a secondary metabolite of microbial synthesis), with its important functional groups like C=O and N–H (Jiang et al. 2003), both O and N contain lone pair of electrons suggesting its capability for metal ions reduction, subsequent fabrication of different NPs that would be incorporated and/or conjugated with the reducing agent, and as a stabilizing agent that could prevent the precipitation and aggregation of metal NPs (Mosallam et al. 2018; El-Sayyad et al. 2019). Finally, some comparative and survey studies reporting the incorporation of HupA with different nano-structured compounds are listed in Table 6.

Conclusion and future approaching

The wide applications of the AChE inhibitors especially in AD treatment as there is a continuous increase in the number of AD patients, and the feasibility of AChE inhibitors production by microbial fermentation approach make it necessary to do excessive research efforts to discover more novel microbial AChE inhibitors. In addition, more microbial strain enhancement protocols are needed to be applied. As a recommendation, besides the conventional submerged fermentation (SMF), solid-state fermentation (SSF) may be a promising alternative for the production of AChE inhibitors. Over the years, SSF proved to be a promising system for the production of many valuable products. SSF has many advantages over the conventional SMF including resistance of microorganisms to catabolic repression, low-cost production process, production of metabolites at higher ,yields and the potentiality of applying agro-industrial wastes as nutritional rich substrates (El-Sayed et al. 2019c, 2020c).

Additionally, the technique of microbial immobilization would be very potential and promising for enhancing the microbial manufacturing of AChE inhibitors, and achieving a continual or a semi continual manufacturing process. This technique is effective for providing a time-consuming production process, and successive fermentation cycles with product extracting and purifying feasibility (Ismaiel et al. 2015; El-Sayed et al. 2019b, 2020d). After the prospective achieving of these steps, it could be possible to transfer the microbial production of AChE inhibitors from an improved lab scale to the promising large-scale industrial production.

References

Abdel-Fattah YR, El Enshasy H, Anwar M, Omar H, Abolmagd E, Abou Zahra R (2007) Application of factorial experimental designs for optimization of cyclosporin a production by Tolypocladium inflatum in submerged culture. J Microbiol Biotechnol 17:1930–1936

Abdelhakim HK, El-Sayed ER, Rashidi FB (2020) Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles with antimicrobial, anticancer, antioxidant and photocatalytic activities by the endophytic Alternaria tenuissima. J Appl Microbiol (Accepted Manuscr Press)

Ali L, Khan AL, Hussain J, Al-Harrasi A, Waqas M, Kang SM, Al-Rawahi A, Lee IJ (2016) Sorokiniol: a new enzymes inhibitory metabolite from fungal endophyte Bipolaris sorokiniana LK12. BMC Microbiol 16:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-016-0722-7

Almasi F, Mohammadipanah F, Adhami H, Hamedi J (2018) Introduction of marine-derived Streptomyces sp . UTMC 1334 as a source of pyrrole derivatives with anti- acetylcholinesterase activity. J Appl Microbiol 125:1370–1382. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.14043

Aly AH, Debbab A, Proksch P (2011) Fungal endophytes: unique plant inhabitants with great promises. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 90:1829–1845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-011-3270-y

Alzheimer’s Association (2017) Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 13:325–373

Ansari SA, Satar R, Perveen A, Ashraf GM (2017) Current opinion in Alzheimer’s disease therapy by nanotechnology-based approaches. Curr Opin Psychiatry 30:128–135

Arruebo M, Valladares M, González-Fernández Á (2009) Antibody-conjugated nanoparticles for biomedical applications. J Nanomater 2009:1–24

Asiya SI, Pal K, El-Sayyad GS, Elkodous MA, Demetriades C, Kralj S, Thomas S (2020) Reliable optoelectronic switchable device implementation by CdS nanowires conjugated bent-core liquid crystal matrix. Org Electron 82:105592

Bagchi D, Barilla J (1998) Huperzine A: boost your brain power. McGraw Hill Professional, New York

Basha SK, Muzammil MS, Dhandayuthabani R, Kumari VS, Kaviyarasu K (2019) Nanoemulsion as oral drug delivery-a review. Curr Drug Res Rev

Behl C, Moosmann B (2002) Serial review : causes and consequences of oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease. Free Radic Biol Med 33:182–191

Bhagat J, Kaur A, Kaur R, Yadav AK, Sharma V, Chadha BS (2016) Cholinesterase inhibitor (Altenuene) from an endophytic fungus Alternaria alternata: optimization, purification and characterization. J Appl Microbiol 121:1015–1025. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.13192

Binghuo Z, Yiqing L, Xiaojun Y, Qifeng L, Minggang L, Mengliang W (2005) Studies on the secondary metabolism of a Streptosporangium sp. Nat Prod Res Dev 17:287–289

Bruch GE, Fernandes LF, Bassi BLT, Alves MTR, Pereira IO, Frézard F, Massensini AR (2019) Liposomes for drug delivery in stroke. Brain Res Bull

Cadet J, Delatour T, Douki T, Gasparutto D, Pouget J-P, Ravanat J-L, Sauvaigo S (1999) Hydroxyl radicals and DNA base damage. Mutat Res Mol Mech Mutagen 424:9–21

Chapla VM, Zeraik ML, Ximenes VF, Zanardi LM, Lopes MN, Cavalheiro AJ, Silva DHS, Young MCM, Marcos L, Bolzani VS, Araújo AR (2014) Bioactive secondary metabolites from Phomopsis sp., an endophytic fungus from Senna spectabilis. Molecules 19:6597–6608. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules19056597

Chen XM, Dong HL, Hu KX, Sun ZR, Chen J, Guo XS (2010) Diversity and antimicrobial and plant-growth-promoting activities of endophytic fungi in Dendrobium loddigesii Rolfe. J Plant Growth Regul 29:328–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-010-9139-y

Choi JY, Roh JY, Wang Y, Zhen Z, Tao XY, Lee JH, Liu Q, Kim JS, Shin SW, Je YH (2012) Analysis of genes expression of Spodoptera exigua larvae upon AcMNPV infection. PLoS One 7

Cismaru L, Popa M (2010) Polymeric nanoparticles with biomedical applications. Rev Roum Chim 55:433–442

Costantino L, Gandolfi F, Tosi G, Rivasi F, Vandelli MA, Forni F (2005) Peptide-derivatized biodegradable nanoparticles able to cross the blood–brain barrier. J Control Release 108:84–96

Cruz-Miranda OL, Folch-Mallol J, Martínez-Morales F, Gesto-Borroto R, Villarreal ML, Taketa AC (2019) Identification of a Huperzine A-producing endophytic fungus from Phlegmariurus taxifolius. Mol Biol Rep:1–7 in press

Deng C, Liu S, Huang C, Pang J, Lin Y (2013) Secondary metabolites of a mangrove endophytic fungus Aspergillus terreus (no. GX7-3B) from the South China Sea. 02:2616–2624. https://doi.org/10.3390/md11072616

Dey A, Bhattacharya R, Mukherjee A, Pandey DK (2017) Natural products against Alzheimer’s disease: pharmaco- therapeutics and biotechnological interventions. Biotechnol Adv 35:178–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2016.12.005

Ding R, Sun BF, Lin GQ (2012) An efficient total synthesis of (−)-huperzine A. Org Lett 14:4446–4449. https://doi.org/10.1021/ol301951r

Doering T (2019) Emulsifying system for microemulsions with high skin tolerance

Dong LH, Fan SW, Ling QZ, Huang BB, Wei ZJ (2014) Indentification of huperzine A-producing endophytic fungi isolated from Huperzia serrata. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 30:1011–1017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-013-1519-6

El-Batal AI, Mosallam FM, Ghorab MM, Hanora A, Gobara M, Baraka A, Elsayed MA, Pal K, Fathy RM, Elkodous MA (2019) Factorial design-optimized and gamma irradiation-assisted fabrication of selenium nanoparticles by chitosan and Pleurotus ostreatus fermented fenugreek for a vigorous in vitro effect against carcinoma cells. Int J Biol Macromol

Elkhenany H, Elkodous MA, Ghoneim NI, Ahmed TA, Ahmed SM, Mohamed IK, El-Badri N (2020) Comparison of different uncoated and starch-coated superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: implications for stem cell tracking. Int J Biol Macromol 143:763–774

Elkodous MA, El-sayyad GS, Abdelrahman IY, El-bastawisy HS, Elrahman A, Mosallam FM, Nasser HA, Gobara M, Baraka A, Elsayed MA, El-batal AI (2019a) Colloids and surfaces B : biointerfaces therapeutic and diagnostic potential of nanomaterials for enhanced biomedical applications. Colloids Surf B: Biointerfaces 180:411–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.05.008

Elkodous MA, El-Sayyad GS, Maksoud MIAA, Abdelrahman IY, Mosallam FM, Gobara M, El-Batal AI (2019b) Fabrication of ultra-pure anisotropic zinc oxide nanoparticles via simple and cost-effective route: implications for UTI and EAC medications. Biol Trace Elem Res:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-019-01894-1

Elkodous MA, El-Sayyad GS, Mohamed AE, Pal K, Asthana N, de Souza Junior FG, Mosallam FM, Gobara M, El-Batal AI (2019c) Layer-by-layer preparation and characterization of recyclable nanocomposite (Cox Ni1−x Fe2O4; X= 0.9/SiO2/TiO2). J Mater Sci Mater Electron 30:8312–8328

Elkodous MA, El-Sayyad GS, Nasser HA, Elshamy AA, Morsi M, Abdelrahman IY, Kodous AS, Mosallam FM, Gobara M, El-Batal AI (2019d) Engineered nanomaterials as potential candidates for HIV treatment: between opportunities and challenges. J Clust Sci 30:531–540

Elkodous MA, El-Sayyad GS, Abdelrahman IY, El Bastawisy HS, Mohamed AE, Mosallam FM, Nasser HA, Gobara M, Baraka A, Elsayed MA, El-Batal AI (2019e) Therapeutic and diagnostic potential of nanomaterials for enhanced biomedical applications. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 180:411–428

Elsabahy M, Wooley KL (2012) Design of polymeric nanoparticles for biomedical delivery applications. Chem Soc Rev 41:2545–2561

El-Sayed ER, Ahmed AS, Abdelhakim HK (2019a) A novel source of the cardiac glycoside digoxin from the endophytic fungus Epicoccum nigrum: isolation, characterization, production enhancement by gamma irradiation mutagenesis and anticancer activity evaluation. J Appl Microbiol 128:747–762. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.14510

El-Sayed ER, Ahmed AS, Hassan IA, Ismaiel AA, El-Din A-ZAK (2019b) Strain improvement and immobilization technique for enhanced production of the anticancer drug paclitaxel by Aspergillus fumigatus and Alternaria tenuissima. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 103:8923–8935. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-019-10129-1

El-Sayed ER, Ahmed AS, Ismaiel AA (2019c) Agro-industrial byproducts for production of the immunosuppressant mycophenolic acid by Penicillium roqueforti under solid-state fermentation: enhanced production by ultraviolet and gamma irradiation. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcab.2019.01.053

El-Sayed ER, Ismaiel AA, Ahmed AS, Hassan IA, El-din AAK (2019d) Bioprocess optimization using response surface methodology for production of the anticancer drug paclitaxel by Aspergillus fumigatus and Alternaria tenuissima: enhanced production by ultraviolet and gamma irradiation. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 18:100996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcab.2019.01.034

El-Sayed ER, Abdelhakim HK, Ahmed AS (2020a) Solid-state fermentation for enhanced production of selenium nanoparticles by gamma-irradiated Monascus purpureus and their biological evaluation and photocatalytic activities. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 1–13 (Accepted Manuscript in Press). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00449-019-02275-7

El-Sayed ER, Abdelhakim HK, Zakaria Z (2020b) Extracellular biosynthesis of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles by Monascus purpureus and their antioxidant, anticancer and antimicrobial activities: yield enhancement by gamma irradiation. Mater Sci Eng C 107:110318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2019.110318

El-Sayed ER, Ahmed AS, Al-Hagar OEA (2020c) Agro-industrial wastes for production of paclitaxel by irradiated Aspergillus fumigatus under solid-state fermentation. J Appl Microbiol (accepted Manuscr press

El-Sayed ER, Ahmed AS, Hassan IA, Ismaiel AA, Zahraa A, El AK (2020d) Semi-continuous production of the anticancer drug taxol by Aspergillus fumigatus and Alternaria tenuissima immobilized in calcium alginate beads. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng (Accepted Manuscript in Press). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00449-020-02295-8

El-Sayyad GS, Mosallam FM, El-Sayed SS, El-Batal AI (2019) Facile biosynthesis of tellurium dioxide nanoparticles by Streptomyces cyaneus melanin pigment and gamma radiation for repressing some Aspergillus pathogens and bacterial wound cultures. J Clust Sci:1–13

Erdogan Orhan I, Orhan G, Gurkas E (2011) An overview on natural cholinesterase inhibitors - a multi-targeted drug class - and their mass production. Mini Rev Med Chem 11:836–842. https://doi.org/10.2174/138955711796575434

Fangfang Z, Mingzi W, Haiyuan L, Yaxuan Z, Shuisheng W (2015) Fermentation optimization of huperzine A produced by endophytic fungi Hypoxylon investiens NX9 from Phlegmariurus phlegmaria. Chin J Pharm 46:827–832

Fonseca-Santos B, Gremião MPD, Chorilli M (2015) Nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Nanomedicine 10:4981

Freitas C, Müller RH (1999) Correlation between long-term stability of solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN™) and crystallinity of the lipid phase. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 47:125–132

Gao H (2016) Progress and perspectives on targeting nanoparticles for brain drug delivery. Acta Pharm Sin B 6:268–286

Garyali S, Kumar A, Reddy MS (2014) Enhancement of taxol production from endophytic fungus Fusarium redolens. Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng 19:908–915. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12257-014-0160-z

Gastaldi L, Battaglia L, Peira E, Chirio D, Muntoni E, Solazzi I, Gallarate M, Dosio F (2014) Solid lipid nanoparticles as vehicles of drugs to the brain: current state of the art. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 87:433–444

Govindasamy G, Pal K, Elkodous MA, El-Sayyad GS, Gautam K, Murugasan P (2019) Growth dynamics of CBD-assisted CuS nanostructured thin-film: optical, dielectric and novel switchable device applications. J Mater Sci Mater Electron 30:16463–16477

Guarnieri D, Muscetti O, Netti PA (2014) A method for evaluating nanoparticle transport through the blood–brain barrier in vitro. In: Drug delivery system. Springer, Berlin, pp 185–199

Han W, Song T, Yang S, Li X, Zhang H, Wu Y, Du D, Wang Y (2015) Identification of alkaloids and huperzine A-producing endophytic fungi isolated from wild Huperzia serrata. J Int Pharm Res 42:507–512

He H, Lu Y, Qi J, Zhu Q, Chen Z, Wu W (2019) Adapting liposomes for oral drug delivery. Acta Pharm Sin B 9:36–48

Heinrich M, Teoh HL (2004) Galanthamine from snowdrop - the development of a modern drug against Alzheimer’s disease from local Caucasian knowledge. J Ethnopharmacol 92:147–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2004.02.012

Hort MA, Alves B d S, Ramires Júnior OV, Falkembach MC, de MS AG, CLF F, Tavella RA, Bidone J, Dora CL, da Silva Júnior FMR (2019) In vivo toxicity evaluation of nanoemulsions for drug delivery. Drug Chem Toxicol:1–10

Huang X, Sun X, Ding B, Lin M, Liu L, Huang H, She Z (2013) A new anti-acetylcholinesterase α -pyrone meroterpene , arigsugacin I , from mangrove endophytic fungus Penicillium sp . sk5GW1L of Kandelia candel. Planta Med 79:1572–1575

Irum W, Anjum T (2012) Production enhancement of Cyclosporin ‘ A ’ by Aspergillus terreus through mutation. Afr J Biotechnol 11:1736–1743. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJB10.1330

Ishiuchi K, Park JJ, Long RM, Gang DR (2013) Production of huperzine A and other Lycopodium alkaloids in Huperzia species grown under controlled conditions and in vitro. Phytochemistry 91:208–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2012.11.012

Ismaiel AA, Ahmed AS, El-Sayed E-SR (2014) Optimization of submerged fermentation conditions for immunosuppressant mycophenolic acid production by Penicillium roqueforti isolated from blue-molded cheeses: enhanced production by ultraviolet and gamma irradiation. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 30:2625–2638

Ismaiel AA, Ahmed AS, El-Sayed ER (2015) Immobilization technique for enhanced production of the immunosuppressant mycophenolic acid by ultraviolet and gamma-irradiated Penicillium roqueforti. J Appl Microbiol 119:112–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.12828

Ismaiel AA, Ahmed AS, Hassan IA, El-Sayed ESR, Karam El-Din AZA (2017) Production of paclitaxel with anticancer activity by two local fungal endophytes, Aspergillus fumigatus and Alternaria tenuissima. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 101:5831–5846. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-017-8354-x

Jawahar N, Meyyanathan SN (2012) Polymeric nanoparticles for drug delivery and targeting: a comprehensive review. Int J Health Allied Sci 1:217

Jeevanandam J, Sundaramurthy A, Sharma V, Murugan C, Pal K, Kodous MHA, Danquah MK (2020) Sustainability of one-dimensional nanostructures: fabrication and industrial applications. In: Sustainable Nanoscale Engineering. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 83–113

Jiang H, Luo X, Bai D (2003) Progress in clinical , pharmacological , chemical and structural biological studies of huperzine A : a drug of traditional Chinese medicine origin for the treatment of Alzheimer ’ s disease. Curr Med Chem 10:2231–2252

Jiang Y, Liu C, Zhai W, Zhuang N, Han T, Ding Z (2019) The optimization design of Lactoferrin loaded HupA nanoemulsion for targeted drug transport via intranasal route. Int J Nanomedicine 14:9217

Ju Z, Wang J, Pan SL (2009) Isolation and preliminary identification of the endophytic fungi which produce Hupzine A from four species in Hupziaceae and determination of Huperzine A by HPLC. Fudan Univ J Med Sci 4:17

Kang X, Liu C, Liu D, Zeng L, Shi Q, Qian K, Xie B (2016) The complete mitochondrial genome of huperzine A-producing endophytic fungus Penicillium polonicum. Mitochondrial DNA Part B Resour 1:202–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802359.2016.1155086

Karami Z, Zanjani MRS, Hamidi M (2019) Nanoemulsions in CNS drug delivery: recent developments, impacts and challenges. Drug Discov Today

Kathe N, Henriksen B, Chauhan H (2014) Physicochemical characterization techniques for solid lipid nanoparticles: principles and limitations. Drug Dev Ind Pharm 40:1565–1575

Khairallah MI, Kassem LAA (2011) Alzheimer’s disease: current status of etiopathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. Pak J Biol Sci 14:257–272. https://doi.org/10.3923/pjbs.2011.257.272

Khalil NM, Mainardes RM (2009) Colloidal polymeric nanoparticles and brain drug delivery. Curr Drug Deliv 6:261–273

Kim W, Song N, Yoo C-D (2001) Quinolactacins Al and A2 , new acetylcholinesterase inhibitors from Penicillium citrinum in MeOH was further purified by reverse phase HPLC. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 54:831–835

Konrath EL, Passos S, Klein-júnior LC, Henriques AT (2013) Alkaloids as a source of potential anticholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer ’ s disease. J Pharm Pharmacol 65:1701–1725. https://doi.org/10.1111/jphp.12090

Koshiba T, Yokoshima S, Fukuyama T (2009) Total synthesis of (−)-huperzine A. Org Lett 11:5354–5356

Kumar RS, Pravallika TVS (2019) Microemulsions: transdermal drug delivery systems with enhanced bioavailability. J Drug Deliv Ther 9:835–837

Kurokawa T, Suzuki K, Hayaoka T, Nakagawa T (1993) Cyclophostin, acetylcholinesterase inhibitor from Streptomyces lavendulae. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 46:1315–1318

Lauterbach A, Müller-Goymann CC (2015) Applications and limitations of lipid nanoparticles in dermal and transdermal drug delivery via the follicular route. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 97:152–163

Li WK, Zhou JY, Lin ZW, Hu Z (2007) Study on fermentation condition for production of huperzine A from endophytic fungus 2F09P03B of Huperzia serrata. Chin Med Biotechnol 2:254–259

Li Y, Chen DH, Yan J, Chen Y, Mittelstaedt RA, Zhang Y, Biris AS, Heflich RH, Chen T (2012) Genotoxicity of silver nanoparticles evaluated using the Ames test and in vitro micronucleus assay. Mutat Res Toxicol Environ Mutagen 745:4–10

Li JL, Huang L, Liu J, Song Y, Gao J, Jung JH, Liu Y, Chen G (2015) Acetylcholinesterase inhibitory dimeric indole derivatives from the marine actinomycetes Rubrobacter radiotolerans. Fitoterapia 102:203–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fitote.2015.01.014

Lim W-H, Goodger JQD, Field AR, Holtum JAM, Woodrow IE (2010) Huperzine alkaloids from Australasian and southeast Asian Huperzia. Pharm Biol 48:1073–1078

Lin Y, Wu X, Feng S, Jiang G, Luo J, Zhou S (2001) Five Unique Compounds : Xyloketals from Mangrove Fungus Xylaria sp . from the South China Sea Coast. J Organomet Chem 66:6252–6256

Liu D, Gong J, Dai W, Kang X, Huang Z, Zhang H-M, Liu W, Liu L, Ma J, Xia Z (2012) The genome of Ganderma lucidum provide insights into triterpense biosynthesis and wood degradation. PLoS One 7

Luo H, Li Y, Sun C, Wu Q, Song J, Sun Y, Steinmetz A, Chen S (2010) Comparison of 454-ESTs from Huperzia serrata and Phlegmariurus carinatus reveals putative genes involved in lycopodium alkaloid biosynthesis and developmental regulation. BMC Plant Biol 10:209

Ma X, Gang DR (2008) In vitro production of huperzine A, a promising drug candidate for Alzheimer’s disease. Phytochemistry 69:2022–2028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.04.017

Mahajan DS, Roy I, Xu G, Yong K-T, Ding H, Aalinkeel R, Reynolds LJ, Sykes ED, Nair BB, Lin YE (2010) Enhancing the delivery of anti retroviral drug “Saquinavir” across the blood brain barrier using nanoparticles. Curr HIV Res 8:396–404

Maksoud MIAA, El-Sayyad GS, Ashour AH, El-Batal AI, Abd-Elmonem MS, Hendawy HAM, Abdel-Khalek EK, Labib S, Abdeltwab E, El-Okr MM (2018) Synthesis and characterization of metals-substituted cobalt ferrite [Mx Co(1-x) Fe2O4;(M= Zn, Cu and Mn; x= 0 and 0.5)] nanoparticles as antimicrobial agents and sensors for Anagrelide determination in biological samples. Mater Sci Eng C 92:644–656

Maksoud MIAA, El-ghandour A, El-Sayyad GS, Awed AS, Fahim RA, Atta MM, Ashour AH, El-Batal AI, Gobara M, Abdel-Khalek EK (2019) Tunable structures of copper substituted cobalt nanoferrites with prospective electrical and magnetic applications. J Mater Sci Mater Electron 30:4908–4919

Marco L, Carreiras M (2006) Galanthamine, a natural product for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Recent Pat CNS Drug Discov 1:105–111. https://doi.org/10.2174/157488906775245246

Meng X, Mao Z, Lou J, Xu L, Zhong L, Peng Y, Zhou L, Wang M (2012) Benzopyranones from the endophytic fungus Hyalodendriella sp. Ponipodef12 and their bioactivities. Molecules 17:11303–11314. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules171011303

Meng Q, Wang A, Hua H, Jiang Y, Wang Y, Mu H, Wu Z, Sun K (2018) Intranasal delivery of huperzine A to the brain using lactoferrin-conjugated N-trimethylated chitosan surface-modified PLGA nanoparticles for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Nanomedicine 13:705

Mirab F, Wang Y, Farhadi H, Majd S (2019) Preparation of gel-liposome nanoparticles for drug delivery applications. In: 2019 41st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC). IEEE, pp 3935–3938

Mohamed T, Rao PN (2011) Alzheimer’s disease: emerging trends in small molecule therapies. Curr Med Chem 18:4299–4320. https://doi.org/10.2174/092986711797200435

Mohinudeen K, Devan K, Srivastava S (2019) Bioprocessing of endophytes for production of high-value biochemicals. In: Secondary metabolites of plant growth promoting rhizomicroorganisms. Springer, Berlin, pp 353–390

Mosallam FM, El-Sayyad GS, Fathy RM, El-Batal AI (2018) Biomolecules-mediated synthesis of selenium nanoparticles using Aspergillus oryzae fermented Lupin extract and gamma radiation for hindering the growth of some multidrug-resistant bacteria and pathogenic fungi. Microb Pathog 122:108–116

Mukherjee S, Ray S, Thakur RS (2009) Advantages and problems of Slns and other nanoparticles. Indian J Pharm Sci 71:349–358

Müller RH, Radtke M, Wissing SA (2002) Nanostructured lipid matrices for improved microencapsulation of drugs. Int J Pharm 242:121–128

Murao S, Hayashi H (1986) Physostigmine and N - norphysostigmine, insecticidal I a. Agric Biol Chem 50:523–524. https://doi.org/10.1080/00021369.1986.10867419

Naseri N, Valizadeh H, Zakeri-Milani P (2015) Solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers: structure, preparation and application. Adv Pharm Bull 5:305

Neumann R, Peter HH (1987) Insecticidal organophosphates: nature made them first. Experientia 43:1235–1237

Ohlendorf B, Schulz D, Erhard A, Nagel K, Imhoff JF (2012) Geranylphenazinediol, an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor produced by a Streptomyces species. J Nat Prod 75:1400–1404

Omura S, Kuno F, Otoguro K, Sunazuka T, Shiomi K, Masuma R, Iwai Y (1995) Arisugacin, a novel and selective inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase from Penicillium sp. FO-4259. J Antibiot 48(7):745–746

Pal K, Elkodous MA, Mohan MLNM (2018) CdS nanowires encapsulated liquid crystal in-plane switching of LCD device. J Mater Sci Mater Electron 29:10301–10310

Pal K, Sajjadifar S, Elkodous MA, Alli YA, Gomes F, Jeevanandam J, Thomas S, Sigov A (2019) Soft, self-assembly liquid crystalline nanocomposite for superior switching. Electron Mater Lett 15:84–101

Pandey S, Sree A, Sethi DP, Kumar CG, Kakollu S (2014) A marine sponge associated strain of Bacillus subtilis and other marine bacteria can produce anticholinesterase compounds. Microb Cell Factories 13:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2859-13-24

Parekh S, Vinci VA, Strobel RJ (2000) Improvement of microbial strains and fermentation processes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 54:287–301

Patel PA, Patil SC, Kalaria DR, Kalia YN, Patravale VB (2013) Comparative in vitro and in vivo evaluation of lipid based nanocarriers of Huperzine a. Int J Pharm 446:16–23

Patočka J (2012) Natural cholinesterase inhibitors from mushrooms. Mil Med Sci Lett 81:40–44. https://doi.org/10.31482/mmsl.2012.005

Paula A, Teles C, Takahashi JA (2013) Paecilomide , a new acetylcholinesterase inhibitor from Paecilomyces lilacinus. Microbiol Res 168:204–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2012.11.007

Peer D, Karp JM, Hong S, Farokhzad OC, Margalit R, Langer R (2007) Nanocarriers as an emerging platform for cancer therapy. Nat Nanotechnol 2:751

Pinu FR, Villas-Boas SG, Aggio R (2017) Analysis of intracellular metabolites from microorganisms: quenching and extraction protocols. Metabolites 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo7040053

Poh Y, Ng S, Ho K (2019) Formulation and characterisation of 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate-in-oil microemulsions as the potential vehicle for drug delivery across the skin barrier. J Mol Liq 273:339–345

Pope CN, Brimijoin S (2018) Cholinesterases and the fi ne line between poison and remedy. Biochem Pharmacol:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2018.01.044

Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, Ferri CP (2013) The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dement 9:63–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.007

Qian C, Decker EA, Xiao H, McClements DJ (2013) Impact of lipid nanoparticle physical state on particle aggregation and β-carotene degradation: potential limitations of solid lipid nanoparticles. Food Res Int 52:342–349

Qiao M, Ji N, Miao F, Yin X (2011) Steroids and an oxylipin from an algicolous isolate of Aspergillus flavus. Magn Reson Chem 49:366–369. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrc.2748

Reis CP, Neufeld RJ, Ribeiro AJ, Veiga F (2006) Nanoencapsulation I. Methods for preparation of drug-loaded polymeric nanoparticles. Nanomed Nanotechnol Biol Med 2:8–21

Schroeder A, Kost J, Barenholz Y (2009) Ultrasound, liposomes, and drug delivery: principles for using ultrasound to control the release of drugs from liposomes. Chem Phys Lipids 162:1–16

Sekhar Rao KC, Divakar S, Karanth NG, Sattur A (2001) (2 ’ ,3 ’ ,5 ’ -Trihydroxyphenyl)tetradecan-2-ol, a novel acetylcholinesterase inhibitor from Chrysosporium sp. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 54:848–849

Sheng J, Han L, Qin J, Ru G, Li R, Wu L, Cui D, Yang P, He Y, Wang J (2015) N-trimethyl chitosan chloride-coated PLGA nanoparticles overcoming multiple barriers to oral insulin absorption. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 7:15430–15441

Shu S, Zhao X, Wang W, Zhang G, Cosoveanu A, Ahn Y, Wang M (2014) Identification of a novel endophytic fungus from Huperzia serrata which produces huperzine A. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 30:3101–3109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-014-1737-6

Singh B, Thakur A, Kaur S, Chadha BS, Kaur A (2012) Acetylcholinesterase inhibitory potential and insecticidal activity of an endophytic Alternaria sp. from ricinus communis. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 168:991–1002. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-012-9835-0

Singh V, Haque S, Niwas R, Srivastava A, Pasupuleti M, Tripathi CKM (2017) Strategies for fermentation medium optimization: an in-depth review. Front Microbiol 7:1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.02087

Souto EB, Wissing SA, Barbosa CM, Müller RH (2004) Development of a controlled release formulation based on SLN and NLC for topical clotrimazole delivery. Int J Pharm 278:71–77

Staniek A, Woerdenbag HJ, Kayser O (2008) Endophytes: exploiting biodiversity for the improvement of natural product-based drug discovery. J Plant Interact 3:75–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/17429140801886293

Stierle A, Strobel G, Stierle D (1993) Taxol and taxane production by Taxomyces andreanae, an endophytic fungus of Pacific yew. Science (80- ) 260:214–216

Strobe G, Daisy B (2003) Bioprospecting for microbial endophytes and their natural products. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 67:491–502. https://doi.org/10.1128/MMBR.67.4.491

Strobel GA (2003) Endophytes as sources of bioactive products. Microbes Infect 5:535–544

Su J, Yang M (2015) Huperzine A production by Paecilomyces tenuis YS-13, an endophytic fungus isolated from Huperzia serrata. Nat Prod Res 29:1035–1041. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786419.2014.980245

Su J, Liu H, Guo K, Chen L, Yang M, Chen Q (2017) Research advances and detection methodologies for microbe-derived acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: a systemic review. Molecules 22:176199. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22010176

Thirugnanasambandan T, Pal K, Sidhu A, Elkodous MA, Prasath H, Kulasekarapandian K, Ayeshamariam A, Jeevanandam J (2018) Aggrandize efficiency of ultra-thin silicon solar cell via topical clustering of silver nanoparticles. Nano Struct Nano Objects 16:224–233

Ting Y, Yun W, Ze Z, Yulian W, Xiaojiang Z, Shikun H, Xin M (2015) Optimization of extraction process for huperzine A from Huperzia serrata. Food Sci 36:57–62. https://doi.org/10.7506/spkx1002-6630-201517052

Tiwari PM, Vig K, Dennis VA, Singh SR (2011) Functionalized gold nanoparticles and their biomedical applications. Nanomaterials 1:31–63

Unluturk S (2017) Impact of irradiation on the microbial ecology of foods. In: Quant microbiol food process model microb ecol, 1st edn. Wiley, pp 176–193

Wang R, Yan H, Tang XC (2006) Progress in studies of huperzine A, a natural cholinesterase inhibitor from Chinese herbal medicine. Acta Pharmacol Sin 27:1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00255.x

Wang Z, Wang J, Zhang H, Tang X (2008) Huperzine A exhibits anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects in a rat model of transient focal cerebral ischemia. J Neurochem 106:1594–1603

Wang Y, Yan RM, Zeng QG, Zhang ZB, Wang D, Zhu D (2011a) Producing huperzine A by an endophytic fungus from Huperzia serrata. Mycosystema 30:255–262

Wang Y, Zeng QG, Zhang ZB, Yan RM, Wang LY, Zhu D (2011b) Isolation and characterization of endophytic huperzine A-producing fungi from Huperzia serrata. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 38:1267–1278

Wang F, Zhai Y, Chen L, Yang Y, Cheng Z (2014) Isolation and identification of an endophytic bacterium with acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity derived from oyster and the optimization of fermentation conditions. J Qingdao Agric Univ (Natural Sci 4:284–289

Wang M, Sun M, Hao H, Lu C (2015a) Avertoxins A − D, prenyl asteltoxin derivatives from Aspergillus versicolor Y10, an endophytic fungus of Huperzia serrata. J Nat Prod:5–8. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00600

Wang Z, Ma Z, Wang L, Tang C, Hu Z, Chou G, Li W (2015b) Active anti-acetylcholinesterase component of secondary metabolites produced by the endophytic fungi of Huperzia serrata. Electron J Biotechnol 18:399–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejbt.2015.08.005

Weigang Z, Wenjie H, Tao W, Baofu Q (2013) Optimization of the extraction technique of huperzine A by response surface method. Guangdong Chem Ind 11

Wen MM, El-Salamouni NS, El-Refaie WM, Hazzah HA, Ali MM, Tosi G, Farid RM, Blanco-Prieto MJ, Billa N, Hanafy AS (2017) Nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems for Alzheimer’s disease management: technical, industrial, and clinical challenges. J Control Release 245:95–107

Williams P, Sorribas A, Howes MJR (2011) Natural products as a source of Alzheimer’s drug leads. Nat Prod Rep 28:48–77. https://doi.org/10.1039/c0np00027b

Wissing SA, Kayser O, Müller RH (2004) Solid lipid nanoparticles for parenteral drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 56:1257–1272

Wollen KA (2010) Alzheimer’s disease: the pros and cons of pharmaceutical, nutritional, botanical and stimulatory therapies. Altern Med Rev 15:223–244

Wong CW, San Chan Y, Jeevanandam J, Pal K, Bechelany M, Elkodous MA, El-Sayyad GS (2019) Response surface methodology optimization of mono-dispersed MgO nanoparticles fabricated by ultrasonic-assisted sol–gel method for outstanding antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities. J Clust Sci:1–23

Wright S, Huang L (1989) Antibody-directed liposomes as drug-delivery vehicles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 3:343–389

Wu B, Ohlendorf B, Oesker V, Wiese J, Malien S, Schmaljohann R, Imhoff JF (2014) Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors from a marine fungus Talaromyces sp. strain LF458. Mar Biotechnol 17:110–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10126-014-9599-3

Xiao-qion Z, Ya-xuan Z, Fang-fang Z, Sai-nan C, Xiao-qiang H, Sheng WS (2015) Screening of high HupA- producing strain by protoplast mutation. Strait Pharm J 27:238–242

Xu F, Tao W, Cheng L, Guo L (2006) Strain improvement and optimization of the media of taxol-producing fungus Fusarium maire. Biochem Eng J 31:67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bej.2006.05.024

Yang C-R, Zhao X-L, Hu H-Y, Li K-X, Sun X, Li L, Chen D-W (2010) Preparation, optimization and characteristic of huperzine a loaded nanostructured lipid carriers. Chem Pharm Bull 58:656–661

Yang G, Wang Y, Tian J, Liu JP (2013) Huperzine A for Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. PLoS One:8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0074916

Yue-sheng D, Zhi-hui Z, Qian Z, Hua Z, Xin-Hua L, Wei S, Yue-qi S, Ying M, Ya-Mei M, Bing-kun H (2002) N98-1021 A, a selective acetylcholinesterase inhibitors derived from microorganisms. Chin J Antibiot 27:260–263

Zaki AG, El-shatoury EH, Ahmed AS, Al-hagar OEA (2019) Production and enhancement of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, huperzine A, from an endophytic Alternaria brassicae AGF041. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 103:5867–5878. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-019-09897-7

Zhang ZB, Zeng QG, Yan RM, Wang Y, Zou ZR, Zhu D (2011) Endophytic fungus Cladosporium cladosporioides LF70 from Huperzia serrata produces Huperzine A. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 27:479–486. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-010-0476-6

Zhang L, Han L, Qin J, Lu W, Wang J (2013) The use of borneol as an enhancer for targeting aprotinin-conjugated PEG-PLGA nanoparticles to the brain. Pharm Res 30:2560–2572

Zhang FF, Wang MZ, Zheng YX, Liu HY, Zhang XQ, Wu SS (2015a) Isolation and characterzation of endophytic Huperzine A-producing fungi from Phlegmariurus phlegmaria. Microbiology 84:701–709. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0026261715050185

Zhang G, Wang W, Zhang X, Xia Q, Zhao X, Ahn Y, Ahmed N, Cosoveanu A, Wang M, Wang J, Shu S (2015b) De novo RNA sequencing and transcriptome analysis of colletotrichum gloeosporioides ES026 reveal genes related to biosynthesis of huperzine A. PLoS One 10

Zhang RH, Li LQ, Wang C, Lu XJ, Shi T, Xu JF, Song LC, Wang HF (2015c) Pretreatment with Huperzine A-loaded poly (lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles protects against lethal effects of Soman-induced in mice. In: Key Engineering Materials. Trans Tech Publ, pp 1374–1382

Zhang S, Ma Q, Huang S, Dai H, Guo Z (2015d) Phytochemistry Lanostanoids with acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity from the mushroom Haddowia longipes. Phytochemistry 110:133–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.12.012

Zhao B, Moochhala SM, Tham SY (2004) Biologically active components of Physostigma venenosum. J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci 812:183–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.08.031

Zhao XM, Wang ZQ, Shu SH, Wang WJ, Xu HJ, Ahn YJ, Wang M, Hu X (2013) Ethanol and methanol can improve huperzine A production from EndophyticColletotrichum gloeosporioides ES026. PLoS One 8:4–12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0061777

Zhou SL, Yang F, Lan SL, Xu N, Hong YH (2009) Huperzine A producing conditions from endophytic fungus in SHB Huperzia serrata. J Microbiol 3:32–36

Zhu D, Wang J, Zeng Q, Zhang Z, Yan R (2010) A novel endophytic Huperzine A-producing fungus, Shiraia sp. Slf14, isolated from Huperzia serrata. J Appl Microbiol 109:1469–1478. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04777.x

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their appreciation to Prof. Dr. Ashraf S. Ahmed (Professor of Microbiology, Plant Research Department, Nuclear Research Center, Atomic Energy Authority) for his continuous help and support. This work was also supported by the Nuclear Research Center, Atomic Energy Authority, Egypt. The authors also acknowledge the P.I. of Nanotechnology Research Unit (Prof. Dr. Ahmed I. El-Batal) for supporting this work under the project “Nutraceuticals and Functional Foods Production by using Nano/Biotechnological and Irradiation Processes.” Finally, the author Gharieb S. El-Sayyad would like to thank Chemical Engineering Department, Military Technical College (MTC), Egyptian Armed Forces, Cairo, Egypt, for the continued support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AGZ start data and formal analysis, mini-review investigation, conceived and designed research, conducted experimental methodology, writing—original draft, and revise—review and editing. ERE start data and formal analysis, mini-review investigation, conceived and designed research, conducted experimental methodology, writing—original draft, and revise—review and editing. MAK start data and formal analysis, mini-review investigation, conceived and designed research, conducted experimental methodology, writing—original draft, and revise—review and editing. GSE start data and formal analysis, mini-review investigation, conceived and designed research, conducted experimental methodology, writing—original draft, and revise—review and editing. All authors read and approved the mini-review.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

This review does not contain any deal with humans or animals.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zaki, A.G., El-Sayed, ES.R., Abd Elkodous, M. et al. Microbial acetylcholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s therapy: recent trends on extraction, detection, irradiation-assisted production improvement and nano-structured drug delivery. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 104, 4717–4735 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-020-10560-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-020-10560-9