Abstract

Evolutionary economists are increasingly interested in developing policy implications. As a rule, contributions in this field implicitly assume that policy should focus on the encouragement of learning and innovation. We argue that, from an individualistic perspective, this position is not easy to justify. Novelty and evolutionary change have in fact a rather complex normative dimension. In order to cope with this, the evolutionary approach to policy-making needs to be complemented with an account of welfare the background assumptions of which are compatible with an evolutionary world-view. Standard welfare economics is unsuited to the job, since the orthodox way to conceptualize welfare as the satisfaction of given and rational preferences cannot be applied in a world in which preferences tend to be variable and incoherent. We argue that, in order to deal with the specific normative issues brought up in an evolving economy, welfare should be conceptualized in a procedural way: At the individual level, it should be understood as the capacity and motivation to engage in the ongoing learning of instrumentally effective preferences. Evolutionary-naturalistic insights into the way human agents bring about, value, and respond to novelty-induced change turn out to be a valuable input into this extended concept of welfare. Finally, some implications of this concept are explored.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Evolutionary economists have not been entirely silent on normative issues. Sartorius (2003: ch. 6) and Binder (2010) discuss notions of welfare from an explicitly evolutionary perspective. Earlier contributions include Dopfer (1976: 19–29), Nelson (1977: 129–143), Nelson (1981), and Nelson and Winter’s (1982: ch. 15) largely ignored programmatic call for a “normative evolutionary economics”. See also Hodgson (1999: ch. 11), Witt (1996), Witt (2003: 89–91), and the sections on “progress” in Van den Van den Bergh and Kallis (2009).

In the following, we will refrain from using “Darwinian” language in the sense of metaphors or analogies from Darwinian biology. The jury is still out on the issue of whether notions such as “variation” or “selection” can be used in evolutionary economics without biasing the analysis in undesirable ways (Witt 2008; Aldrich et al. 2008). Biases may be particularly strong in the realm of normative reasoning, as this kind of analysis is unrelated to anything known in biology. See also FN 6, below.

Strictly speaking, it is a logical fallacy, though, to predict that innovation will continue to benefit the “average” individual in the future. After all, the future tends to be unknown (Witt 2003).

Note, however, that insofar as this concept relates to the criterion of Kaldor-Hicks efficiency, it is highly contentious. See FN 33, below.

As Hodgson (1993: 25) observes, “[i]t is still widely assumed that evolutionary thinking involves the rejection of any kind of state meddling, subsidy or intervention, and the support for laissez-faire on the basis of the idea of ‘survival of the fittest’”. Notice that Hodgson himself does neither share this assumption (on which see also Whitman 1998) nor endorse any such kind of policy.

In contrast, in Keynes’ framework, normative economics proper is about the critical analysis of welfare criteria and policy goals per se. We will adopt this distinction in the following. John Neville Keynes (1852–1949), a British economist, was the father of the much better known John Maynard Keynes.

Italics in the original.

See Ludwig Lachmann’s quip that “[i]n a world of unexpected change economic forces generate a redistribution of wealth far more pervasive and ineluctable than anything welfare economists could conceive” (Lachmann 2007: 81, FN 6).

Harsanyi (1982) is the locus classicus for this way of thinking about welfare. See Sugden (2009) on the strong (implicit) value judgments inherent in accounts of this sort. Notice that the orthodox account of welfare is explicitly unconcerned with mental states: “satisfaction” does not refer to any “feeling” of, e.g., “pleasure” (as in classical utilitarianism) but rather denotes a purely technical measure of degree.

Methodologically, this approach was motivated by the supposed lack of reliable scientific knowledge about the process and content of human preference formation. With the rise of evolutionary and behavioral economics (as well as neuroeconomics), this caveat has become obsolete: “non-choice” sources of information on the structure and content of individual preferences are now available and accepted as meaningful by most economists. See Sen (1977a) for the methodological issues involved.

Nevertheless, this first step of instrumental reasoning is often lacking in applied evolutionary economics research, when (implicitly) an omniscient social planner seems to lurk in the background; see Wegner (2005) for some critical thoughts on this.

See Broome (2008): “Democracy has at least two departments. One department is decision making, and here democracy requires that the people’s preferences should prevail... Another department... is the forming of people’s preferences...Our preferences about complex matters depend on our beliefs, and democracy requires a process of discussion, debate and education, aimed at informing and improving people’s beliefs... The role of economists in a democracy belongs in the second department, not the first... Economists should aim to influence preferences, not take preferences for granted.”

See his suggestion in “Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy” that “we shall call that system relatively more efficient which we see reason to expect would in the long run produce the larger stream of consumers’ goods per equal unit of time” (Schumpeter 1942: 190, italics omitted) and the fact that here and in related work he never really elaborates upon this notion of efficiency or welfare. On Schumpeter’s complex, insightful and often contradictory reasoning about welfare, see Schubert (2009).

See, e.g. Baumol (1990) who defines as “productive” those kinds of entrepreneurship that stimulate growth and productivity.

See Nelson (1977: 18): “A powerful normative structure can help in the sorting out, weighing, and education of values, and thus can facilitate agreement among groups even in situations where agreement originally seemed implausible.”

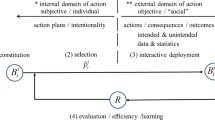

See Witt (2003: 87): “The policy maker gathers information to learn about the consequences [of some policy]... For example, if the proclaimed goal is a ‘more just’ income distribution, it is only with the experience made with some concrete redistributive policy measure that the policy maker finds out what kind of ‘justice’ actually results (which is a factual question) and whether its observed consequences are indeed considered to be worthwhile (which is a normative question). It may turn out that other goals are also being affected... The experience made will most probably be one of trade-offs which may induce ... revaluations at the level of the goals. A prominent case are inconsistencies... between the attainment of short run goals and the attainment of long run goals which are discovered only later.” Note that all this does not affect the categorical (logical) distinction between positive and normative statements.

“GDP growth” as a policy goal is subject to intense critical scrutiny, particularly in the field of ecological economics.

On a more applied level, Potts (2004) stresses the importance of the systemic view on welfare in the context of assessing financial “bubbles”. Starting from the premise that bubbles are “natural mechanisms of economic growth and evolution”, he argues that they are “ultimately a sign of system health and vigour, not of decadence and decay” (ibid.: 16), and that policy should appreciate their beneficial effects: “Inside a bubble, the cost of experimentation, and therefore variety generation, is lowered and,... the process of structural change is accelerated... Learning is accelerated within a bubble, and radically new business ideas can get a start, as can radically new products” (ibid.: 18–19). His policy implications are straightforward: “Policy should not worry about bubbles; if anything, and where it is safe to do so, it should perhaps even encourage them.” (ibid.: 20). In light of recent events in global financial markets, this may sound absurd. Potts, however, has a point in stressing the systemic aspect of welfare: In order to establish the conditions necessary for an evolving economy to work smoothly, bubbles do have some functional properties. The argument gets into trouble, though, as soon as the normative and the instrumental levels are mixed: Fast learning and variety generation would then be judged as desirable goals per se. Potts seems to be aware of this risk of producing counter-intuitive policy advice (note his caveat: “where it is safe to do so”), but does not elaborate upon this issue.

See also the references given by Vanberg (1994b: 465–66).

Hayek (2009) constructs a strong moral obligation for man to support “rapid material progress”, which leads him ultimately to argue that “we are ... the captives of progress; even if we wished to, we could not sit back and enjoy at leisure what we have achieved” (ibid.: 52). On this tension in Hayek’s normative argument, see also Vanberg (1994a, b: 183) and Gray (1999: 154).

Purely procedural criteria would neglect any considerations related to outcomes (or patterns of outcomes) whatsoever, thereby running the risk of generating strong counter-intuitive conclusions. They are hardly ever consistently defended (Nozick 1974 being a notable exception), which is why we will not consider them here.

My translation from the German original.

Cf. Buchanan’s(1977: 27–30) related hint at the possibility of “spontaneous disorder”.

Italics added.

Note that this does not apply to Kirzner’s entrepreneur, whose arbitraging brings the economy back into equilibrium.

This holds as long as an egalitarian and non-discriminatory allocation of basic rights is maintained.

To paraphrase Rawls’ well-known critique, the offsetting involved in applying this criterion does not take seriously “the distinction between persons” (Rawls 1971: 27). Add to this the manifold technical problems widely discussed in the literature (e.g. Scitovsky 1941; Little 1957; Gowdy 2004). Anticipating most of this, Schumpeter (1954: 1072, FN 9) dismisses the Kaldor-Hicks criterion in just one sentence.

To illustrate, consider Rawls’ difference principle (“inequality of winners and losers is just as long as losers are better off in the regime allowing the inequality than in a regime disallowing it”) which frames issues of justice in terms of all-purpose “primary social goods” rather than in terms of preference-based utility (Rawls 1971: ch. 2).

“Just” and “legitimate” are used synonymously in the following.

Again, Rawls‘ notion of “primary social goods” may illustrate this approach.

See Hanusch and Pyka (2007: 284).

Italics partly omitted.

I.e., not necessarily involving comparisons between alternative social states (such as bundles of goods); see Kahneman and Sugden (2005: 164) for the terminology.

The following five paragraphs rely heavily on Witt (2001) whose account of want learning is inspired by Benthamite hedonism (Kahneman et al. 1997), need-theoretic approaches (e.g. Georgescu-Roegen 1954; Ironmonger 1972) – without, however, endorsing a ‘Maslovian’ hierarchy of needs – and the theory of instrumental conditioning (Herrnstein 1990). For methodological details, see Witt and Schubert (2010).

In the long run, though, the intensity of the acquired want tends to weaken unless the original association with the underlying need is occasionally re-established (Witt 2001: 28–29).

See the related evidence given by, e.g., Frey and Sutzer (2007) on the human tendency to mispredict the hedonic impact of consumer decisions.

See Cordes and Schubert (2010) for a formal model of cultural learning that captures this idea.

There may be exceptions, e.g. with respect to the consumption of addictive substances (see below).

At a basic methodological level, there are, however, two important differences between the capability approach and our account of well-being. First, at its origins, the capability approach was motivated by the inability of the orthodox concept of welfare to cope with normative issues arising out of preference endogeneity, in particular the problem of “adaptive preference formation” (Qizilbash 2008). The solution was to define well-being in an essentially objectivist way, i.e. independent of subjective preferences (or the way they change). By contrast, our account defines well-being in more (albeit not perfectly) “subjectivist” terms. Second, our account is much more firmly grounded in empirical research on human behavior and preference formation. Notice, e.g., the conspicuous lack of interest in behavioral economics in Sen’s most recent writings (e.g. Sen 2009).

See Sen (1996).

To illustrate, all available empirical evidence shows that child-rearing has a significant negative impact on parents’ happiness (see, e.g., Di Tella et al. 2003; Clark 2007; Blanchflower 2009). However, many people decide to have children and to raise them, simply on the grounds of other goals in life (“achievements”, say, or the compliance with social norms).

See also Sen (2009) on the implausibility of a non-pluralist notion of welfare, in particular in the context of accounts of justice.

My italics.

On the inevitable incompleteness of evaluations in matters of social justice, see Sen (2009: 103–08).

Note that the evolutionary model of preference formation discussed in Section 4.1 above, may back the following qualification of “libertarian paternalist” tools. According to the model, agents acquire preferences on a non-cognitive and, based on this, on a “higher” cognitive level. Given that the former provides the essential building blocks (“needs”) for the subsequent refinement achieved on the cognitive level, one may argue that libertarian paternalism should refrain from using any tool that affects non-cognitive learning processes, i.e., that cannot be made subject to conscious deliberation at the level of cognitive reasoning. In this way, our evolutionary model would help in providing an explicit justification to an argument that is usually made ad hoc; see, e.g., Bovens (2008).

References

Aldrich HE, Hodgson GM, Hull DL, Knudsen T, Mokyr J, Vanberg VJ (2008) In defence of generalized Darwinism. J Evol Econ 18:577–596

Anand P, Gray A (2009) Obesity as market failure: could a ‘deliberative economy’ overcome the problem of paternalism? Kyklos 62:182–190

Andersen ES (2004) Population thinking and evolutionary economic analysis: exploring Marshall’s fable of the trees. Mimeo

Ariely D, Loewenstein G, Prelec D (2006) Tom Sawyer and the construction of value. J Econ Behav Organ 60:1–10

Atkinson AB (2009) Economics as a moral science. Economica 76:791–804

Audretsch DB, Grillo I, Thurik AR (2007) Explaining entrepreneurship and the role of policy: a framework. In: Handbook of research in entrepreneurship policy. Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 1–17

Baumol W (1990) Entrepreneurship: productive, unproductive, and destructive. J Polit Econ 98:893–921

Beaulier S, Caplan B (2007) Behavioral economics and perverse effects of the welfare state. Kyklos 60:485–507

Bianchi M (2002) Novelty, preferences, and fashion: when goods are unsettling. J Econ Behav Organ 47:1–18

Binder M (2010) Elements of an evolutionary theory of welfare. Routledge, London

Blanchflower DG (2009) International evidence on well-being. In: Kruger AB (ed) Measuring the subjective well-being of nations: national accounts of time use and well-being. Chicago University Press, Chicago, pp 155–226

Blanchflower DG, Oswald AJ (2005) Some policy implications of behavioral economics–Happiness and the human development index: the paradox of Australia. Aust Econ Rev 38:307–318

Boeri T, Börsch-Supan A, Tabellini G (2001) Would you like to shrink the welfare state? A survey of European citizens. Econ Pol 16:9–50

Boulding KE (1981) Evolutionary economics. Sage, Beverly Hills

Bovens L (2008) The ethics of Nudge. In: Grüne-Yanoff T, Hansson SO (eds) Preference change: approaches from philosophy, economics and psychology. Springer, Berlin, pp 207–220

Broome J (1996) Choice and value in economics. In: Hamlin AP (ed) Ethics and economics, vol. I. Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 65–85

Broome J (2008) Why economics needs ethical theory. In: Basu K, Kanbur R (eds) Arguments for a better world: essays in honor of Amartya Sen. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 7–15

Bruni L, Sugden R (2007) The road not taken: how psychology was removed from economics, and how it might be brought back. Econ J 117:146–173

Buchanan JM (1977) Freedom in constitutional contract. Texas A & M University Press, College Station

Buchanan JM (2005) Afraid to be free: dependency as desideratum. Public Choice 124:19–31

Camerer C, Issacharoff S, Loewenstein G, O’Donoghue T, Rabin M (2003) Regulation for conservatives: behavioral economics and the case for ‘asymmetric paternalism’. Univ PA Law Rev 151:1211–1254

Cantner U, Pyka A (2001) Classifying technology policy from an evolutionary perspective. Res Policy 30:759–775

Clark DA (2006) The capability approach: its development, critiques and recent advances. In: Clark DA (ed) The Elgar Companion to development studies. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 32–45

Clark AE (2007) Born to be mild? Cohort effects don’t (fully) explain why well-being is U-shaped in age. IZA Discussion Paper No. 3170, IZA, Bonn, Germany

Cordes C (2008) A potential limit on competition. J Bioecon 10:127–144

Cordes C, Schubert C (2010) Role models that make you unhappy: light paternalism, social learning and welfare. Papers on Economics & Evolution #1022. Max Planck Institute of Economics, Jena

Di Tella R, McCulloch R, Oswald A (2003) The macroeconomics of happiness. Rev Econ Stat 85:809–827

Dopfer K (1976) Introduction: towards a new paradigm. In: Dopfer K (ed) Economics in the future. Macmillan, London, pp 3–35

Dosi G, Marengo L, Pasquali C (2006) How much should society fuel the greed of innovators? On the relations between appropriability, opportunities and rates of innovation. Res Policy 35:1110–1121

Earl PE, Potts J (2004) The market for preferences. Camb J Econ 28:619–633

Elster J (1982) Sour grapes–utilitarianism and the genesis of wants. In: Sen AK, Williams B (eds) Utilitarianism and beyond. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 219–238

Foss NJ (2006) Evolutionary Economics and Economic Policy. Available online at: http://organizationsandmarkets.com/2006/08/02/evolutionary-economics-and-economic-policy/

Frank RH (2008) Should public policy respond to positional externalities? J Public Econ 92:1777–1786

Frey BS, Stutzer A (2002) What can economists learn from happiness research? J Econ Lit 60:402–435

Frey BS, Sutzer A (2007) What happiness research can tell us about self-control problems and utility mispredictions. In: Frey BS, Stutzer A (eds) Economics and psychology: a promising new cross-disciplinary field. MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 169–195

Frey BS, Benz M, Stutzer A (2004) Introducing procedural utility: not only what, but also how matters. J Inst Theor Econ 160:377–401

Georgescu-Roegen N (1954) Choice, expectations, and measurability. Q J Econ 68:503–534

Gowdy JM (2004) The revolution in welfare economics and its implications for environmental valuation and policy. Land Econ 80:239–257

Gray J (1999) Hayek on liberty. Routledge, London

Hanusch A, Pyka A (2007) Principles of Neo-Schumpeterian economics. Camb J Econ 31:275–289

Harsanyi J (1982) Morality and the theory of rational behavior. In: Sen AK, Williams B (eds) Utilitarianism and beyond. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 39–62

Hayek FA (1948) Individualism and economic order. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Hayek FA (1976) Law, legislation and liberty, vol. II. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Hayek FA (1978) The confusion of language in political thought. In: New studies in philosophy, politics, economics and the history of ideas. Routledge, London, pp 71–97

Hayek FA (1988) The fatal conceit. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Hayek FA (2009) The common sense of progress. In: The constitution of liberty. Routledge, London, pp 36–48

Henrekson M (2005) Entrepreneurship: a weak link in the welfare state? Ind Corp Change 14:437–467

Herrnstein RJ (1990) Behavior, reinforcement and utility. Psychological Science 1:217–224

Hodgson GM (1993) Economics and evolution: bringing life back into economics. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor

Hodgson GM (1999) Economics and Utopia: why the learning economy is not the end of history. Routledge, London

Ironmonger DS (1972) New commodities and consumer behavior. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Kahneman D, Wakker PP, Sarin R (1997) Back to Bentham? Explorations of experienced utility. Q J Econ 112:375–405

Kahneman D, Sugden R (2005) Experienced utility as a standard of policy evaluation. Environ Resource Econ 32:161–181

Kerstenetzky CL (2007) Hayek and Popper on ignorance and intervention. J Inst Econ 3:33–53

Keynes JN (1917) The scope and method of political economy. Macmillan, London

Köszegi B, Rabin M (2008) Choices, situations, and happiness. J Public Econ 92:1821–1832

Lachmann L (2007) Capital and its structure. Sheed Andres and McMeel, Kansas City

Lessig L (1995) The regulation of social meaning. Univ Chic Law Rev 62:943–1045

Little IMD (1957) A critique of welfare economics. Oxford University Press, London

Metcalfe JS (2001) Institutions and progress. Ind Corp Change 10: 561–586

Metcalfe JS (2005) Systems failure and the case for innovation policy. In: Llerena P, Matt M (eds) Innovation policy in a knowledge-based economy. Springer, Berlin, pp 47–74

Mokyr J (2000) Innovation and its enemies: the economic and political roots of technological inertia. In: Olson M, Kähkönen S (eds) A not-so-dismal science. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 61–91

Myrdal G (1933) Das Zweck-Mittel Denken in der Nationalökonomie. Zeitschrift für Nationalökonomie 4:305–329

Nelson RR (1977) The Moon and the Ghetto. Norton, New York

Nelson RR (1981) Assessing private enterprise: an exegesis of tangled doctrine. Bell J Econ 12:93–111

Nelson RR (1990) Capitalism as an engine of growth. Res Policy 19:193–214

Nelson RR (1995) Recent evolutionary theorizing about economic change. J Econ Lit 33:48–90

Nelson RR, Winter SG (1982) An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change. Belknap Press, Cambridge

Ng Y-K (2003) From preference to happiness: towards a more complete welfare economics. Soc Choice Welf 20:307–350

North DC (1990) Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Nozick R (1974) Anarchy, state and utopia. Basic Books, New York

Ostrom E (2005) Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton University Press

Pelikan P (2002) Why economic policies need comprehensive evolutionary analysis. In: Pelikan P, Wegner G (eds) Evolutionary thinking on economic policy. Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 15–45

Potts J (2001) Knowledge and markets. J Evol Econ 11:413–431

Potts J (2004) Liberty bubbles. Policy 20:15–21

Qizilbash M (2008) The adaptation problem, evolution and normative economics. Papers on Economics & Evolution #0708. Max Planck Institute of Economics, Jena

Rabin M (2002) A perspective on psychology and economics. Eur Econ Rev 46:657–685

Rawls J (1971) A Theory of Justice. Belknap Press, Cambridge

Robbins L (1935) An Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science. Macmillan, London

Samuelson PA (1938) A note on the pure theory of consumer’s behaviour. Economica 5:61–71

Sartorius C (2003) An Evolutionary Approach to Social Welfare. Routledge, London

Scanlon TM (1991) The moral basis of interpersonal comparisons. In: Elster J, Roemer JE (eds) Interpersonal comparisons of well-being. Cambridge University Press, MA, pp 17–44

Schubert C (2009) Welfare Creation and Destruction in a Schumpeterian World. Papers on Economics & Evolution #0913. Max Planck Institute of Economics, Jena

Schumpeter JA (1912) Theorie der wirtschaftlichen Entwicklung. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin

Schumpeter JA (1942) Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. Allen & Unwin, London

Schumpeter JA (1954) History of Economic Analysis. Allen & Unwin, London

Scitovsky T (1941) A note on welfare propositions in economics. Rev Econ Stud 9:77–88

Sen AK (1977a) Rational fools: a critique of the behavioral foundations of economic theory. Philos Public Aff 6:317–344

Sen AK (1977b) On weights and measures: informational constraints in social welfare analysis. Econometrica 45:1539–1572

Sen AK (1979) Equality of What? Tanner Lecture on Human Values. Available online at: http://www.tannerlectures.utah.edu/lectures/documents/sen80.pdf

Sen AK (1980) Equality of what. In: McMurrin SM (ed) The tanner lectures on human values. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, pp 197–220

Sen AK (1985) Commodities and Capabilities. Basic Books, New York

Sen AK (1988) On Ethics and Economics. Basil Blackwell, Oxford

Sen AK (1993) On the Darwinian view of progress. Popul Dev Rev 19:123–137

Sen AK (1996) On the foundations of welfare economics: utility, capability, and practical reason. In: Farina F, Hahn F, Vanucci S (eds) Ethics, rationality, and economic behavior. Clarendon, Oxford, pp 50–65

Sen AK (1999) Development as Freedom. Knopf, New York

Sen AK (2009) The Idea of Justice. Allen Lane, London

Sobel D (1994) Full-information accounts of well-being. Ethics 104:784–810

Stam E (2008) Entrepreneurship and innovation policy. Jena Economic Research Papers #2008-006

Sugden R (1993) Normative judgments and spontaneous order: the contractarian element in Hayek’s thought. Const Polit Econ 4:393–424

Sugden R (2004) The opportunity criterion: consumer sovereignty without the assumption of coherent preferences. Am Econ Rev 94:1014–1033

Sugden R (2007) The value of opportunities over time when preferences are unstable. Soc Choice Welf 29:665–682

Sugden R (2008) Why incoherent preferences do not justify paternalism. Const Polit Econ 19:226–248

Sugden R (2009) On nudging: a review of nudge: improving decisions about health, wealth and happiness. Int J Econ Bus 16:365–373

Sunstein CR, Thaler RH (2003) Libertarian paternalism. Am Econ Rev, Papers & Proceedings 93:175–179

Thaler RH, Sunstein CR (2008) Nudge: improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Princeton University Press, New Haven

Van den Bergh JCJM, Kallis G (2009) Evolutionary policy. Papers on economics & evolution #0902. Max Planck Institute of Economics, Jena

Van Praag M, Versloot PH (2007) What is the value of entrepreneurship? A review of recent research. Small Bus Econ 29:351–382

Vanberg VJ (1994a) Cultural evolution, collective learning, and constitutional design. In: Reisman D (ed) Economic thought and political theory. Kluwer, Boston, pp 171–204

Vanberg VJ (1994b) Hayek’s legacy and the future of liberal thought: rational liberalism vs. evolutionary agnosticism. J des Econ et des Etud Hum 5:451–481

Vanberg VJ (2006) Human intentionality and design in cultural evolution. In: Schubert C, von Wangenheim G (eds) Evolution and design of institutions. Routledge, London, pp 197–212

Vis B, van Kersbergen K (2007) Why and how do political actors pursue risky reforms? J Theor Polit 19:153–172

Wegner G (1997) Economic policy from an evolutionary perspective–a new approach. J Inst Theor Econ 153:485–509

Wegner G (2005) Reconciling evolutionary economics with liberalism. In: Dopfer K (ed) Economics, evolution and the state. Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 58–77

von Weizsäcker CC (1971) Notes on endogenous change of tastes. J Econ Theory 3:345–372

von Weizsäcker CC (2010) Cost-Benefit Analysis with Adaptive Preferences. Mimeo, Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods, Bonn, Germany

Whitman DG (1998) Hayek contra pangloss on evolutionary systems. Const Polit Econ 9:45–66

Witt U (1987) Individualistische Grundlagen der evolutorischen Ökonomik. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen

Witt U (1996) Innovations, externalities and the problem of economic progress. Public Choice 89:113–130

Witt U (2000) Genes, culture, and utility. Papers on Economics & Evolution #0009. Max Planck Institute of Economics, Jena

Witt U (2001) Learning to consume–a theory of wants and the growth of demand. J Evol Econ 11:23–36

Witt U (2003) Economic policy making in evolutionary perspective. J Evol Econ 13:77–94

Witt U (2004) Beharrung und Wandel – ist wirtschaftliche Evolution theoriefähig? Erwägen – Wissen – Ethik 15:33–45

Witt U (2008) What is specific about evolutionary economics? J Evol Econ 18:547–575

Witt U, Schubert C (2010) Extending the informational basis of welfare economics–the case of preference dynamics. Papers on Economics & Evolution #1005. Max Planck Institute of Economics, Jena

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schubert, C. Is novelty always a good thing? Towards an evolutionary welfare economics. J Evol Econ 22, 585–619 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-011-0257-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-011-0257-x