Abstract

This paper uses panel data on over 200 regions of Europe during the years 2010–2015 to study the relationship between the quality of institutions and the capacity of local authorities and stakeholders to effectively protect and support cultural heritage, using new designations in the UNESCO World Heritage List as a proxy. Besides analyzing the spatial distribution of World Heritage sites across European regions, we test whether the location of a region matters for the chances of obtaining a new UNESCO designation by controlling for the stock of World Heritage in the surrounding regions, and whether low regional government quality is an obstacle to inclusion of sites into the List. While we can detect no significant spill-overs from the stock of World Heritage in surrounding regions, we find evidence that local government quality matters for the chances of a region gaining a UNESCO site designation.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The recent decades have seen growing awareness among international institutions, academic circles, and the public at large of the crucial role of good and democratic governance for economic and social development. The United Nations system claims to base its actions on the idea of a governance that “promotes equity, participation, pluralism, transparency, accountability and the rule of law, in a manner that is effective, efficient and enduring, (…) advances development, by bringing its energies to bear on such tasks as eradicating poverty, protecting the environment, ensuring gender equality, and providing for sustainable livelihoods.” (UNDP 2014), and the World Bank sees good governance as “the capacity of the government to effectively formulate and implement sound policies” (Kaufmann et al. 2009). At the same time, the scholarly literature has recurrently focused on the relationship between formal and informal institutions and economic development, unveiling their historical role in shaping countries’ and regions’ current economic performance or their importance for the effectiveness of public policy (Acemoglu et al. 2001; Rodrik et al. 2004; Tabellini 2010; Rodríguez-Pose 2013).

Despite the growing interest in the role of the quality of institutions in enhancing social welfare and promoting local development, there has been little research so far on whether the ability of a polity to express a good government—the agathòs dimension from the Ancient Greek culture that the title of this paper refers to—can help preserve the richness, beauty and value of cultural heritage—the kalòs dimension of a local community. Indeed, as a form of cultural and territorial capital, heritage stores or gives rise to cultural value that fosters the identity of places and the cohesion of communities, but also contributes, in combination with other inputs, to the production of goods and services that generate economic and social impacts (Throsby, 1999; Camagni and Capello 2013). Similarly, cultural heritage is an asset owning public good characteristics (Serageldin 1999; Peacock and Rizzo 2008), whose protection requires the contribution and coordination of several private and public actors, as well as the design and implementation of appropriate public policies and regulations. For historical reasons, cultural heritage is particularly relevant in Europe and its conservation and support have become major policy issues in the last decades, with local governments and stakeholders playing an increasingly active role in promoting heritage sites for culture-led development strategies (Van Balen and Vandesande, 2016).

The question we address here is if the quality of sub-national institutions throughout Europe is an important ingredient for the protection and promotion of heritage. More specifically, we use an index of the quality of government across European regions to account for institutional heterogeneity and investigate how this measure is associated with the inclusion of new heritage sites into the UNESCO World Heritage List, an event that we consider as a proxy of regional authorities’ and stakeholders’ ability to support cultural heritage as a factor of regional competitiveness.

In doing so, we take a regional perspective by combining a novel dataset on UNESCO World Heritage designations of European regions for the period 2010–2015 with region-level data on quality of government institutions gathered by the Quality of Government Institute at the University of Gothenburg. Moreover, since we deal with territorial units whose spatial location might have potentially important implications, we make explicit use of spatial econometric methods in investigating the determinants of inclusion in the UNESCO List.

The main results of our empirical analysis can be briefly summarized as follows. First, after controlling for several factors at both regional and national level, the chances of a region having a heritage site inscribed in the UNESCO List in a given year are estimated to be positively associated with the quality of the government of the region, particularly when measured in terms of control of corruption and of quality of public services provided. On the other hand, as far as inter-regional interdependencies are concerned we find no significant spill-over on a region from the stock of World Heritage in surrounding regions. At the same time, the number of regions in a country turns out to have a weakly significant negative impact on a region’s success in site inscription, pointing to within-country competition between regions for nominating and inscribing sites in the World Heritage List.

The contribution of this paper is threefold. First, it addresses the effect of the quality of institutions on a novel dimension of regional performance. The quality of government has been found to affect regions’ performance along several dimensions, namely the capacity to innovate, the effectiveness of regional policies, the return to investment, the presence of small and medium-sized enterprises in the local economy, and the attractiveness of regions to migrants (Rodriguez-Pose and Di Cataldo 2015; Rodriguez-Pose and Garcilazo 2015; Ketterer and Rodríguez-Pose 2015; Nistotskaya et al. 2015; Crescenzi et al. 2016). We contribute to that literature by unveiling how the quality of regional government is associated with the capacity to protect and promote cultural heritage at the local level through the inscription process into the World Heritage List. Indeed, while suggestive of the existence of a genuinely causal impact of the quality of regional government on its performance in the protection of cultural heritage, the lack of truly experimental circumstances in our research design implies that this evidence should only be considered as a first step in the investigation of the hitherto unexplored ability of good government to best preserve regional patrimony.

Secondly, the paper is connected to the emerging literature on political, economic and institutional determinants of World Heritage designations (Bertacchini and Saccone 2012; Frey et al. 2013; Parenti and De Simone 2015; Bertacchini et al. 2016). Factors such as a country’s income level, economic power, tourism specialization and active involvement on the World Heritage Committee sessions have been found to have an impact on the likelihood for a country to have sites included World Heritage List. While these studies use data at the country level, we contribute to this literature by providing new evidence as to whether the same factors hold at the European subnational level.

The final novel contribution of this paper is to go beyond the conventional country-level analysis of UNESCO World Heritage site allocation and attribute the existing heritage sites across the over 200 regions of Europe—the geographic area hosting the highest share of World Heritage designations in the world—by employing their unique GIS coordinates from the UNESCO World Heritage Center Database. This makes it possible to study for the first time the local determinants of their inscription as well as to test for inter-regional spillovers and spatial dependence patterns.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the relationship between the quality of institutions and heritage preservation and promotion through UNESCO designations. In Sect. 3 we show the spatial distribution of World Heritage sites across the European regions, while in Sect. 4 we introduce the empirical models and discuss the results of the econometric analysis. Section 5 concludes.

2 Cultural heritage, UNESCO designations and the quality of regional institutions

Cultural heritage, in particular in its tangible forms, has often been interpreted as a capital asset contributing to societies’ welfare. Heritage sites, monuments and historic buildings grant a flow of benefits over time, including private benefits to owners and users of heritage, as well as “public” benefits to wider stakeholders and future generations (Rizzo and Throsby 2006). In addition, and similarly to physical, human and natural capital, cultural heritage is subject to depreciation and requires adequate investment in order to be preserved and supported (Revelli 2013). While the economic literature has often focused on the collective good dimension of cultural heritage to analyze the dilemma and policy mechanisms for its preservation, there is a growing recognition of how this feature can contribute to local development processes (Greffe et al. 2005; Le Blanc 2010; Throsby 2007; Capello and Perucca 2017).

Coupled with a trend of administrative devolution and decentralization in the cultural sector, this perspective has become particularly popular in Europe in the last two decades and has led to the growing importance of the regional and local dimension in the governance of cultural heritage and design of heritage-led development strategies (D’angelo and Vesperini 2000). As noted by Rizzo (2004), sub-central public intervention can be optimal in heritage policy when the support to cultural heritage has the objective of promoting local economic development by enhancing the attractiveness and tourist potential of heritage sites or of stimulating the local identity and cohesion of communities.

At the same time, concern with the quality of institutions has become a mode of investigation into the conditions that promote local development in the regional science literature (Rodríguez-Pose 2013; Pike et al. 2017). As the quality of institutions matters in facilitating collective action, mobilizing stakeholders and integrating them into the development processes (Pike et al. 2017), we expect that the same factor is at work in enhancing the recognition, protection and promotion of cultural heritage, in particular the more this asset is used by regional governments and stakeholders to achieve local development objectives.

To empirically account for the capacity to protect and promote cultural heritage at the regional level, we use the number of new sites included in the UNESCO World Heritage List as a proxy. The World Heritage List is the main implementing mechanism of the 1972 UNESCO World Heritage Convention, an international agreement that seeks to encourage the identification, protection and preservation of cultural and natural heritage that is considered to be of outstanding value to humanity. Inclusion of properties on the List is the result of a selection process that occurs during the annual World Heritage Committee sessions. Even though the original goals of the World Heritage List are primarily related to the preservation and protection of heritage sites, the process of inscription of UNESCO designations is increasingly regarded in recent years as a tool for territorial marketing or as a place-making catalyst (Leask and Fyall 2006).

At the same time, although the proposal and selection of UNESCO World Heritage remain a prerogative of national governments, the role of local authorities and actors in supporting the nomination of heritage sites has become increasingly relevant, in particular in the European context. After over 40 years of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, most of the European countries have already included in the List the most outstanding heritage sites of national relevance. New nominations on the World Heritage List, albeit still proposed for their outstanding universal value, are more likely to be expressions of cultural heritage with greater local significance, whose nomination often implies the involvement of regional governments and coalitions of local stakeholders.

As noted by Van der Aa (2005), a successful nomination increasingly depends on the mobilization of local stakeholders and political and financial help from the local government is often needed to continue with the nomination and to prepare a nomination document. This trend is particularly evident when looking at nomination dossiers of new World Heritage sites in Europe in the 2010–15 period we analyze. Of 25 properties inscribed in the List, 17 nominations either directly involve regional governments as proposer or other local private and public actors as responsible authorities for the heritage property. This occurs for nominations of cultural heritage extending over relatively large areas of a region, such as landscapes or heritage complexes (e.g., the Langhe vineyards in Italy, the Champagne Hills in France, the Mining basin of Nord Pas de Calais in France or Gavleborg Farm houses, in Sweden) but also for single iconic sites (the Margravial Opera House Bayreuth proposed by the Free State of Bavaria in 2012).

In addition, it is worth noticing that the changes occurred in the last decade in the selection process of the UNESCO World Heritage List (UNESCO 2007), which allow a state party to submit only up to two complete nominations per year, have possibly increased the competition between regions in the same country to propose and have their heritage sites included in the List. As a result, political and institutional differences across regions may have a greater influence on the selection process of heritage sites.

Turning to the quality of institutions at the regional level, we use the sub-national Quality of Government (QoG) index proposed by Charron et al. (2014, 2015). Developed by the Quality of Government Institute at the University of Gothenburg (Sweden), the index is commonly considered as one of the few sources of information for systematic comparison of institutional performance across European regions. It is based on survey data from samples of respondents across countries and regions within the EU and addresses three main dimensions of government quality, namely public sector corruption, impartiality and effectiveness in the provision of three public services (education, healthcare, law enforcement). A region’s QoG index is constructed by combining the national score of the Worldwide Governance Indicators (Kaufmann et al. 2009) standardized for the EU sample, with the variation of the QoG index obtained from the regional survey with respect to the country average.

Information on the regional quality of government has been published for three years, based on subsequent rounds of surveys conducted in 2010, 2013 and 2017.Footnote 1 The regionalization of the perceived quality of government institutions unveils interesting patterns that we aim at exploiting here, notably the very large variance of the index in a number of countries including Italy, Spain and Portugal, relative to more homogeneous countries like Denmark, Sweden or the Netherlands.

The QoG index has been used so far to address several research questions, notably how the quality of regional government institutions affect the innovative capacity of regions (Rodriguez-Pose and Di Cataldo 2015), the rates of small and medium-sized enterprises in the local economy (Nistotskaya et al. 2015), the return to public investments (Rodriguez-Pose and Garcilazo; Crescenzi et al. 2016) and the regional attractiveness to migrants (Ketterer and Rodríguez-Pose 2015). Although it is based on perception of local government institutions in three specific areas of public service provision (health care, education, and law enforcement), the regional QoG index can serve as a proxy of the quality of local institutions and its mediating role in enhancing the effectiveness of public policies in other domains, such as heritage.

Protection and promotion of heritage can be considered in many respects as a form of collective provision of public goods and services (Throsby 2010), for the quality of political decision-making and governance mechanisms between local stakeholders influence the outcome of this domain. Furthermore, as the regional quality of government is positively associated with social trust (Charron et al. 2014), it is very likely that more cohesive communities exhibit stronger preferences for the conservation and support to their heritage assets as well as a relatively greater coordination of the local authorities and stakeholders to achieve this goal.

3 The distribution of World Heritage sites across the EU regions

Studies and statistics concerning UNESCO World Heritage have usually focused on the distribution of sites at the country level, as state parties are the key actors within the UNESCO World Heritage Convention. Conversely, there has been little attention to a regional perspective on UNESCO World Heritage and in particular to the distribution of World Heritage sites across the European regions. Europe is the area hosting the highest share of World Heritage properties, with some countries, namely France, Italy and Spain, ranking at the top for the number of sites in the World Heritage List. While data of UNESCO World Heritage sites at the regional level have been recently used to analyze the tourism attractiveness of European regions (Panzera et al. 2021), a regional perspective on European World Heritage can also be useful to verify in a more fine-grained way whether geographical imbalances in the List noticed at the global level and between-countries do occur across European regions too. Further, through this approach it is possible to add insights into the spatial dependence of regions as to the localization of World Heritage sites, overcoming national boundaries.

To compute the number of World Heritage sites that can be attributed to each region of Europe, we have employed the official information about the spatial location of heritage properties drawn from the UNESCO World Heritage Center Database (Source: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list). The database provides unique GIS coordinates that we use to identify the region (NUTS2 level) in which the heritage property is located. In cases where the UNESCO site area extends over multiple regions, the site is assigned to the region according to the official coordinates.Footnote 2

As for trans-boundary sites (those sites that are recorded in the List as belonging to different countries), we adopt the following approach. For those sites that are located at the border of neighboring regions in two or more countries, we assign them equally to all involved regions. Conversely, we exclude transnational serial properties that are extremely scattered across countries and regions because it is difficult to identify the leading region in the World Heritage nomination process.Footnote 3 Finally, we do not make any distinction between cultural, natural and mixed properties as defined by UNESCO World Heritage Convention. Differentiating between cultural and natural sites would create difficulties in the European context due to the very low number of natural sites.Footnote 4

UNESCO sites are spread in a relatively homogeneous way through the European continent, with 63.5% of the regions having at least one property included on the List. However, the regions scoring the highest number of sites tend to be located in the Mediterranean area and, in particular, in countries like Italy and Spain that exhibit also the highest number of sites on the List. On the other hand, regions without World Heritage sites are more likely to be found in the United Kingdom and in Central and Eastern Europe.

Figure 1 displays the distribution of World Heritage sites in 2015 across European regions (NUTS2), providing a first illustration of the most visible spatial patterns.

In order to detect spatial dependence of World Heritage sites across the European regions, we first compute the global Moran’s I statistic as a measure of association, and then local indicators of spatial association (LISA). LISA provide insights at the local level by showing the tendency of observed phenomena to locate or not in neighboring regions and are computed through a local Moran’s statistic where the population is a group of neighboring regions depending on a contiguity criterion (Anselin 1995).

Figure 2a and 2b presents the two measures using the first-order queen contiguity neighborhood criterion, where the set of neighbors of region i includes all regions sharing a border with it, and where each neighboring region j is attributed the same weight.Footnote 5

The spatial association of UNESCO World Heritage sites across European regions measured by the Global Moran’s I statistic is positive (0.16), but it is not particularly high.Footnote 6 Looking at the Moran scatterplot (Fig. 2a), this is due to a relatively large number of regions in the upper left and lower right quadrants, which indicate spatial clustering of observations with diverging values. In other words, while some European regions with many (few or none) World heritage sites do tend to cluster in space, there are parts of the continent where regions with many (few) sites are surrounded by regions with few (many) sites. The map of local indicator of spatial association (LISA) displayed in Fig. 2b highlights the most relevant local patterns of concentration between regions. Even if a large part of reported local Moran’s I statistics are not significant, a look at both the high-high (red) and low-low (blue) clusters confirms the descriptive finding identified in Fig. 1. Regions with high number of World Heritage sites tend to be located in Southern European countries, whereas clusters of regions scoring low values of heritage sites are more likely to be located in Central and Eastern Europe (including Turkey).

To describe the geographical distribution of World Heritage Sites across the European Regions, Table 1 presents the estimated coefficients from a cross-sectional linear regression including as covariates geographical and historical factors that may have determined the potential of a region to obtain a World Heritage designation.Footnote 7 The size of the regions is a first rough indicator for the potential of having heritage sites included in the List. As expected, the coefficient for this variable is always positive and significant (varying between 5 and 10% significance level, depending on the specification). More interestingly, the number of World Heritage sites is significantly explained by proxies of the cultural potential of the region, based on its historical development. In particular, using Chandler and Fox’s data on the geographical evolution of major urban settlements in history (Chandler and Fox 2013), we construct variables for different historical periods (XI, XVI and XVIII century) reflecting the number of the most populated cities in Europe (top one hundred) located in each region. From an historical perspective, major urban centers have been the loci of the most intense socio-economic activities as well as of the highest achievements in cultural and artistic expression. As a result, one can expect that the more a region has hosted major urban centers during the past, the more World Heritage sites it contains today. As can be noted in Regressions 1–3 in Table 1, the coefficients indicating the effect of the number of major cities in European history on the number of current sites is positive and highly significant, with the distribution of major cities across regions in the XVI century leading to the largest effect on the current number of World Heritage sites. The effect of the historical cultural potential of regions also holds when we use a cumulative variable based on the previous three periods (regression 4).

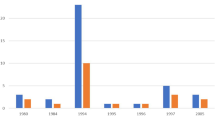

As a final piece of evidence, Fig. 3 presents the distribution of new sites included in the World Heritage List over the period 2010–2015, based on the regional allocation method previously described. With only 25 new listed properties,Footnote 8 the relatively low number of inscriptions is mainly the effect of the rules and procedures adopted in the last decade by UNESCO, which have restricted to one (or two in special cases) the number of nominations that can be submitted by state parties for selection. As a result, as shown in Fig. 3, very few regions have obtained a UNESCO designation in the reference period, with the exception of only two (Sicily in Italy and Izmir in Turkey) with two new listed sites. Interestingly, the regions that have been able to include new sites in the List tend to be relatively clustered in some specific countries (i.e., France, Germany, Portugal, Italy, and Turkey) suggesting that regions’ behavior may still be influenced to some extent by group or country factors.

4 Econometric analysis

4.1 Empirical strategy and variables

To investigate the determinants of the probability of European regions having their sites included in the UNESCO World Heritage List, we focus on two main channels. First, we consider the regional quality of government as a factor affecting the level of protection and support to heritage and, consequently, the ability of a region to obtain the World Heritage designation. Secondly, we test whether the location of a region matters for the chances of its nominations to obtain the World Heritage designation by controlling for the stock of listed heritage sites that are located in the surrounding regions. In fact, the documented process of spatial concentration of world heritage sites might indicate, after controlling for the quality and stock of the heritage endowment, potential spill-overs across regions in heritage policy and their ability to obtain World Heritage designations.

We use a panel data set of European regions r = 1,…,R over six years t = 2010,…,2015. The key variable that we observe at the regional level is a binary variable, \({i}_{rt}\), equaling 1 if a region r has (at least) one new site inscribed into the UNESCO List in a given year t.Footnote 9\({i}_{rt}\) depends in turn on the realization of an underlying (unobserved) score, \({i}_{rt}^{*}\), with \({i}_{rt}=1\left(0\right)\) if \({i}_{rt}^{*}\, \ge\, 0 \, \left(<0\right)\). The \({i}_{rt}^{*}\) score is modelled in Eq. (1):

\({{\varvec{x}}}_{rt}^{{\prime}}\) in Eq. (1) is a vector of regional variables at year t, namely (logarithmic transformations of) population, size, income per capita and number of tourist arrivals per square km. These covariates have been commonly considered as factors affecting countries’ capacity or economic interest to inscribe heritage sites in the UNESCO World Heritage List, and we include them to test their effect at the sub-national level. In particular, the variable on tourist arrivals is intended to capture heterogeneity in tourism potential across regions, with the hypotheses that less attractive regions could be more active in obtaining a World Heritage designation.

The Quality of Government index \({QoG}_{r\stackrel{\sim }{t}}\) is observed in 2010 and 2013, and we set \(\tilde{t}\)= 2010 if t ≤ 2012 and \(\stackrel{\sim }{t}\) = 2013 if t ≥ 2013. \({WH}_{rt-1}\) and \({WH}_{jt-1}\) index the stock of World Heritage sites in regions r and j at time t − 1, respectively. \({\omega }_{rj}\in (\mathrm{0,1})\), r,j = 1,…,R, is an (R × R) set of spatial weights, with \({\omega }_{rj}=1\) if regions r and j are adjacent (i.e., they share a common border), 0 otherwise, so that \(\delta\) captures the impact of the total number of listed sites in the neighborhood at the end of the previous period on the probability of having a site listed in a region in period t. Because the stock of World Heritage sites at the regional level might not be fully informative of the regions’ heritage endowment, we consider the number of properties in the UNESCO Tentative List in region r at time t − 2 (\({T}_{rt-2}\)). As the Tentative List is made of sites which state parties consider to be of outstanding universal value and suitable for inscription on the World Heritage List, this variable is a proxy of the quality and quantity of regions’ total heritage endowment not yet included in the List. The two years lag has been chosen in this case because, according to UNESCO operational guidelines, state parties must submit sites to the Tentative List at least one year prior to the submission of any nomination (UNESCO 2017).

The inclusion of the lagged stock of sites in the World Heritage List deserves some further consideration for potential endogeneity concerns. In fact, one could argue that the same factors that we claim currently influence new inscriptions of World Heritage sites at the regional level may have equally affected the ability to include sites in the World Heritage and Tentative List by regions in the past. In addition, any realization of new site inscriptions at time t (\({i}_{rt}\)) will mechanically enter the lagged stock variable in the next period (\({WH}_{rt-1}\)), thus potentially biasing our estimates in the presence of serial correlation in \({\varepsilon }_{rt}\). As a result, we estimate Eq. (1) by replacing the yearly observations on \({WH}_{rt-1}\) with the 2010 beginning of period value.

As for the Quality of Government index at the regional level (\({QoG}_{r\tilde{t}}\)), we consider both the global index and its sub-components, expressing the quality of public services, impartiality in provision, and control of corruption. We use the values observed in 2010 and 2013 and reported in the dataset released with the 2013 wave, which excludes the observations for the Turkish regions. Previous works (Rodriguez-Pose and Di Cataldo, 2015; Rodriguez-Pose and Garcilazo, 2015; Crescenzi et al., 2016) have adopted the regional quality of government in panel settings, but used only the value observed in one wave. As a result, by using two waves, our approach can capture the within-country evolution of regions’ quality of government during the period of analysis.

While we seek to isolate the determinants of the conservation of heritage at the regional level and the ability to include heritage in the World Heritage List, we cannot completely rule out that this outcome can be influenced by some country-level characteristics that may enable or hinder regions’ activity depending on the procedures of the UNESCO World Heritage nomination and selection process. As a result, we include in our specification the number of regions of a country to capture the effect of the competition between regions in the same country. Further, we consider two additional dimensions of the activity of a country in the World Heritage system that may affect the actual capacity of its regions to inscribe sites in the List. The variable Committee is a binary variable indicating whether or not a country is serving on the World Heritage Committee. Previous works (Bertacchini and Saccone 2012; Frey et al. 2013) suggest that this variable has a positive impact on the inscription of World Heritage sites, as countries that serve the World Heritage Committee in a given year might be more likely to propose and inscribe sites, thus generating a greater chance for the regions within their borders. Finally, we include the total number of years a country has been member of the World Heritage Committee. This variable captures differences in the active involvement of countries in the UNESCO World Heritage system, and may signal the interest of national and local governments in using the World Heritage List as a mechanism for the protection and promotion of their heritage. Table 5 in the Appendix presents the summary statistics of all variables used. We estimate Eq. (1) by Probit with random effects.Footnote 10

4.2 Results

Table 2 summarizes the results obtained by estimating Eq. (1) under different specifications. First, we consider the effect of the stock of World Heritage sites in neighboring regions on the likelihood of obtaining a new inscription either with only world heritage specific variables or with other controls (regressions 5 and 7); next, we consider the regional quality of government scores (regressions 6 and 8); finally, we estimate full models with both effects (regressions 9–11) and also taking into account year fixed effects that pick common time factors, i.e., the specific World Heritage Committee behavior and attitude towards selection of properties to be included in the List in a given annual session.

As for the stock of World Heritage sites in the neighboring regions (Neighboring WH), the coefficient for this variable is never significant under any specification. Thus we can reject the hypothesis that a spatial spill-over impacts the probability to obtain new inscriptions at the regional level.

Conversely, the coefficient on the regional quality of government (QoG) is estimated to be positive and always significant at the 5% level (reg. 6, 8–11), suggesting that local governments that are more accountable are also more likely to support their cultural heritage, leading to a higher chance to obtain the UNESCO World Heritage recognition. Based on the results from regression 11, the estimated marginal effect of an increase in the quality of government at its mean value of 0 by one unit (corresponding to one standard deviation) is around 1%. To appreciate the size of the effect of the QoG variable on the inscription performance of a region, Fig. 4 displays the predicted probability of inscribing in one year a new site according to variation in the regional quality of government (results based on regression 11). For example, a quality of government score equal to 1 (as the one found, e.g., in the Vlaams Gevest region in Belgium) is predicted to generate a 3% probability of inscription of a new site in the World Heritage List during any year, which is five times larger than the corresponding chances in regions where the quality of government score is equal to -1 (e.g., the Abruzzo region in Italy). Interestingly, the 95% confidence intervals become wider as the QoG increases. This finding might be read as evidence that the quality of regional institutions is a necessary, but not sufficient condition for increasing the chances of including sites in the World Heritage List, in the sense that it is extremely unlikely for regions with low levels of QoG to inscribe a new site, while high levels of QoG are associated both with high-performing and with low-performing regions.

As one could expect, a region’s capacity to nominate and inscribe a site in the World Heritage List is positively affected by the number of sites in the Tentative List. This effect is stable over regressions, with a significance level between 5 and 10 percent in fully specified models.

Among the other regional variables, the coefficient of population is statistically significant and with a positive sign. One possible explanation of this result is that more populated European regions tend to have historically more urbanized areas and this may reflects into a larger stock of available cultural heritage. Moreover, the effect of regional income per capita is significant only when the quality of government is not included in the model (reg. 5–6), suggesting that the latter factor is a more robust predictor of regions’ capacity in promoting heritage and inscribing sites in the World Heritage List. Regional tourism pressure does not always show any significant relationship with the likelihood of having a site inscribed.Footnote 11 One reason for this lack of evidence could be that the use of regional tourism data does not perfectly capture the scale at which the tourism-attraction channel expected by the World Heritage designation works (i.e. province or municipal clusters level). More importantly, a deeper inspection of data points out that by using European regional tourism data, several year-region observations of UK are missing, thus reducing the coverage of the dataset. For this reason, in regression 11 and in the following models and specifications, we omit this variable. In this latter case, the number of regions in a country turns out significant at the 10% level and with a negative coefficient, indicating some effect of within-country competition between regions for nominating and inscribing World Heritage sites.

The results also point out how country-level characteristics related to a state’s involvement into the World Heritage Convention influence regions’ outcomes too. In particular, while being member of the World Heritage Committee in a given year by a country does not lead to a significant effect at the regional level, the coefficient of the number of years a country has served to the Committee is positive and highly significant.

The decomposition of the Quality of Government index into its three basic components in Table 3 (Regressions 12–14) provides additional insights into the link between specific institutional factors and the capacity to inscribe World Heritage Sites at the regional level. In all three cases, the main results obtained in previous specifications hold, with the coefficients for the three sub-indexes being positive and significantly different from zero. Interestingly, the component referring to the control of corruption exhibits the highest significance and largest coefficient value among the three sub-indexes, while government impartiality has the lowest significance and smallest effect. This finding is in line with previous research showing that the level of perceived corruption has the strongest and most significant effect on regional performance in various domains, such as innovation capacity (Rodriguez-Pose and Di Cataldo 2015) and presence of small and medium-sized enterprises (Nistotskaya et al. 2015). Similarly, since the conservation and promotion of cultural heritage strongly relies on a community’s social capital as well as on the enforcement of regulations and investment in capital assets, the corruption dimension, rather than the quality and impartiality in the provision of public services, is possibly the one that better captures the capacity of regional governments and local stakeholders to align their actions in heritage policy-making and enforcement.

Considering we find no spatial effect for the stock of World Heritage in neighboring regions on the likelihood of inscription of World Heritage sites, we also test whether spatial spillovers from the presence of heritage sites in neighboring regions occur only within countries, due to national institutional factors which might hinder the operation of the effect across national borders. In regression 15, we employ a spatial weighting matrix that accounts only for within-country adjacent regions, but also under this new configuration the stock of World Heritage sites in adjacent regions does not turn out to be a significant predictor, while the other effects hold.

Focusing on the effect of the stock of World Heritage sites in adjacent regions is justified by a spatial externality-based argument. Yet, there is no reason to exclude that the likelihood of obtaining a new UNESCO designation can be influenced by the outcome of neighboring regions in nominating and obtaining UNESCO designations, or that other regional characteristics included as covariates in the model can display some spatial effects as well. To explore such processes of spatial dependence, we adopt a cross-sectional spatial autoregressive probit model (Le Sage et al. 2011), using a collapsed dataset to a single period. In this case, we estimate the probability that European regions obtain at least one heritage site in the period 2010–2015 by exploiting the cross-sectional variation of our explanatory variables.

The use of a single period cross-sectional dataset is also justified by the fact that the preparation of the World Heritage nomination until the successful inclusion in the List is a lengthy process that might take several years. As a result, analyzing new UNESCO inscriptions by regions on a year-by-year perspective within a panel data approach might be too fine-grained to account for these sticky features of the World Heritage designation process.

As shown in Table 4, estimation of the spatial Probit model does not provide significant evidence of an endogenous process of spatial interaction between nearby regions (columns (16)–(19)), with only some marginally significant evidence of residual spatial auto-correlation (column (20)), probably due to omitted variables having a spatial pattern. Interestingly, though, the estimated effects from the key explanatory variables hold in this cross-sectional specification too, particularly for what concerns the positive and significant impact of the quality of government index. As shown in Fig. 5, differences in the regional quality of government scores have a large impact on the success of regional heritage policy: regions registering a regional QoG score of 1 have an 18% chance to inscribe at least one World Heritage site during the whole period, relative to a 3% probability of regions scoring −1.Footnote 12 Also in this case, 95% confidence intervals widen as the QoG increases.

4.3 Robustness checks

This section resumes further checks we made to test the robustness of our main findings.

To address concerns that sites in the national Tentative Lists might not fully capture heterogeneity in the cultural heritage endowment at the regional level, we adopted alternative measures. A first candidate proxy are the variables we use in Table 1 reflecting the number of most populated cities in European regions for different historical periods. In alternative, we used data collected within the ESPON project (ESPON project 1.3.3, 2004), which provide a measure based on the number of registered monuments and sites in national lists, weighted by the number of "excellence" resources.Footnote 13 Estimated coefficients for these variable, either in addition to or in substitution with the number of sites in the Tentative List, are never statistically significant, nor they alter the other effects.Footnote 14

Moreover, considering that only 25 sites were newly listed as World Heritage properties over the 2010–2015 period, using a binary dependent variable a potential bias can arise for rare events in our estimates. Following King and Zeng (2001), Table 6 in the Appendix reports logistic regression estimation results corrected for rare events and with observations clustered at the region level. In this case, the estimates generally confirm the robustness of the previously identified effects. The estimated coefficients for the quality of regional government, the control of corruption sub-index and the number of years a country has served in the Committee remain statistically significant at 10%, 5% and 1%, respectively. Conversely, the coefficient on the tentative list variable is statistically significant when considering the overall quality of government and its impartiality sub-index.

As additional robustness checks, we present in Tables 7 and 8 regressions using different samples to cope with distinct factors related to the selection process of World Heritage sites.

First, one may argue that the heterogeneity in the number of sites in the Tentative List at regional level is not a pure exogenous factor capturing a region’s heritage endowment eligible for the UNESCO designation. Instead, the distribution of sites in national tentative list may suffer from a political bias influenced by central governments’ decisions or by a bargaining process between authorities at the national and subnational level. While we cannot completely rule out this hypothesis, we restrict our data to regions that have at least one property in the national Tentative List at time t − 2, thus excluding regions that had clearly no chance to obtain a new World Heritage Site over the period and including only regions that benefited from the formation of national Tentative Lists, regardless of the underlying decision-making process (Table 8 in Appendix, regressions 25–28). In this case, while the number of properties in the national tentative list or the number of regions at the country level are no longer significant, the regional quality of government and its sub-indexes are still significantly and positively associated with the probability of obtaining a new World Heritage site designation.

Second, as the country-level variables we selected might only loosely capture the effect of national governments on the regions’ probability of having a site included in the UNESCO List, we consider only regions from European countries that have obtained in one year of the reference period at least one World Heritage site. By restricting the analysis to this subsample, we implicitly presume that the probability of obtaining a new World Heritage site for a region in a given year is conditioned by the capacity of the national government to support and ensure in the World Heritage selection process the inscription of one nomination among the sites available in the Tentative List. As the sample is now reduced to region-year observations of specific countries during the period, in regressions 29 to 32 (Table 8 in Appendix) we use probit estimation omitting country-level variables. The results confirm that regions with a larger number of properties in the national tentative lists have a higher chance to obtain a World Heritage site designation. As for the quality of government and its sub-indexes, the main results hold, even if the significance of the coefficients is lower than in the previous models.

5 Concluding Remarks

This paper has used a newly constructed panel dataset that matches the distribution of UNESCO world heritage sites across over 200 European regions with indicators of quality of public institutions to test whether the characteristics of governments in terms of probity, fairness and ability to provide public services positively affect regions’ capacity to protect and support their heritage, and proxied that capacity by the chances of having their heritage sites nominated and included in the UNESCO World Heritage list. The paper contributes to the literature on the political and economic determinants of UNESCO World Heritage by adding a regional and spatial perspective to the analysis. Further, it contributes to the scholarly debate on the effects of the quality of institutions and governance by providing novel insights in the field of heritage and cultural policies.

Knowledge of the geographical distribution of sites across the European regions has allowed us to give a fresh picture of the spatial pattern of the existing stock of UNESCO sites in Europe as well as to test for the existence of spill-overs from the presence of heritage sites in a region onto the chances of new sites being inscribed in neighboring regions. After controlling for regional and national factors conventionally used to explain the nomination and inscription activity of World Heritage sites, the empirical analysis unveils that the quality of the regional governments positively influences the chances of a region having a heritage site inscribed in the UNESCO list in a given year. Conversely, we find no significant spill-over impact across regions on the ability to obtain World Heritage designations based on the stock of world heritage sites in neighboring regions.

The results of the analysis have relevant policy implications too. They empirically confirm that the effective protection and support to cultural heritage is influenced not only by national heritage policies, but also by indicators of government ‘health’ at the sub-national level that can be considered as proxies of a more general commitment of a local community to mobilize stakeholders for the protection and promotion of its heritage. In particular, high levels of corruption emerge as the main obstacle to effective heritage protection policy in the regions of Europe. Additionally, as for the UNESCO World Heritage selection process, the findings suggest that, at least in the European context, the rules adopted to limit the annual number of national sites to be included in the World Heritage List might have partly shifted the competition from states to regions within the same country, making the accountability of regional governments an increasingly relevant factor for obtaining new designations.

Notes

The regional scores from the three waves of data are not immediately comparable. Due to the process of standardization, adding or subtracting units can impact the scores of other units artificially. However, with each new release, the values of the index from the previous years have been retroactively adjusted with validated techniques (see Charron et al. 2015; Charron and Lapuente 2018).

To give an example, the World Heritage site of the Dolomiti in Italy, that extends through both the Veneto and the Trentino Alto Adige regions, has been assigned to Veneto based on the reported GIS coordinates.

Transnational serial properties are those where two or more spatially distinct components stretch across two or more neighboring countries, as individual components if they create a thematic, functional, historic, stylistic or typological series with other, spatially distinct components.

Natural sites are only about 10% of listed properties in Europe compared to about 20% on the whole World Heritage List.

Because the Queen contiguity weight matrix drops from the analysis 17 neighborless regions (i.e. islands), we also tested a 5-nearest neighbors weight matrix as an alternative approach, obtaining very similar results.

A deeper inspection of the data indicates a Global Moran’s I statistics of 0.23 when considering only the regions in Western European countries (Portugal, Spain, France, UK, Ireland, Italy, Germany and Benelux), while no spatial association (0.07) for the regions in Eastern and Northern Europe.

Following Frey et al. (2013) we have also estimated count data models considering that the dependent variable can only take natural numbers. The results and significance of coefficients are similar in the two settings and for clarity and convenience in interpreting the results we opted for the OLS ones in this case.

The number of new sites considered here for the period 2010-2015 is lower than the actual number of inscriptions as we excluded transnational serial sites for methodological reasons.

To analyze political and economic factors influencing the World Heritage sites selection, previous empirical works (Bertacchini and Saccone, 2012; Bertacchini et al., 2016) have used samples of nominated properties by countries and constructed dependent variables based on the inscription as successful outcome. This strategy cannot be adopted here as in the period of analysis almost all the nominated properties by European countries have been successfully included in the World Heritage List.

A random effects specification is preferable to a fixed effects one in this context because of significant between-group variation in the explanatory variables and little within-group variation (due to the rare occurrence of non-zero outcomes) in the dependent variable.

This result is confirmed also using alternative variables and specifications related to regional tourism, such as using lagged variables, limiting to foreign tourist arrivals or considering the regional population instead of the surface as denominator.

Predictive probabilities are computed from standard probit estimates.

However, it is worth noticing that compared to the information provided in national tentative lists for UNESCO World Heritage designation, ESPON indicator is based on less recent information. Further, as the data come from available national and regional listing systems, there might be concern of potential measurement inconsistencies due to differences in national or regional definitions of monuments and heritage sites and data availability.

Results for this robustness check are available upon requests from the authors.

References

Acemoglu D, Johnson S, Robinson J (2001) The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. Am Econ Rev 91:1369–1401

Anselin L (1995) Local indicators of spatial association. Geogr Anal 27:93–115

Bertacchini E, Liuzza C, Meskell L, Saccone D (2016) The politicization of UNESCO World Heritage decision making. Public Choice 167:95–129

Bertacchini E, Saccone D (2012) Toward a political economy of world heritage. J Cult Econ 36:327–352

Camagni R, Capello R (2013) Regional competitiveness and territorial capital: a conceptual approach and empirical evidence from the European Union. Reg Stud 47(9):1383–1402

Capello R, Perucca G (2017) Cultural capital and local development nexus: Does the local environment matter?. In: Socioeconomic environmental policies and evaluations in regional science. Springer, Singapore, pp 103–124

Chandler T, Fox G (2013) 3000 Years of Urban Growth. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Charron N, Dijkstra L, Lapuente V (2014) Regional governance matters: quality of government within European Union member states. Reg Stud 48:68–90

Charron N, Dijkstra L, Lapuente V (2015) Mapping the regional divide in Europe: a measure for assessing quality of government in 206 European regions. Soc Indic Res 122:315–346

Charron N, Lapuente V (2018) Quality of government in EU regions: spatial and temporal patterns. QoG Working Paper Series 2018.1.

Crescenzi R, Di Cataldo M, Rodriguez-Pose A (2016) Government quality and the economic returns of transport infrastructure investment in European regions. J Reg Sci 56:555–582

D’angelo M, Vespérini P (2000) Cultural policies in Europe: regions and cultural decentralisation. Council of Europe, Strasbourg

ESPON project 1.3.3 (2004) The Role and Spatial Effects of Cultural Heritage and Identity (2004–2006).

Frey B, Pamini P, Steiner L (2013) Explaining the world heritage list: an empirical study. Int Rev Econ 60:1–19

Greffe X, Pflieger S, Noya A (2005) Culture and local development. OECD, Paris

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., and M. Mastruzzi (2009) Governance Matters VIII: Aggregate and Individual Governance Indicators for 1996–2008. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 4978. World Bank, Washington, DC

Ketterer T, Rodríguez-Pose A (2015) Local quality of government and voting with one’s feet. Ann Reg Sci 55:501–532

King G, Zeng L (2001) Logistic regression in rare events data. Political Anal 9(2):137–163

Leask A, Fyall A (2006) Managing world heritage sites. Routledge

Le Blanc A (2010) Cultural districts, a new strategy for regional development? The South-East Cultural District in Sicily. Reg Stud 44(7):905–917

LeSage JP, Kelley Pace R, Lam N, Campanella R, Liu X (2011) New Orleans business recovery in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. J R Stat Soc Ser A (Stat Soc) 174(4):1007–1027

Nistotskaya M, Charron N, Lapuente V (2015) The wealth of regions: quality of government and SMEs in 172 European regions. Environ Plann C Gov Policy 33:1125–1155

Panzera E, de Graaff T, de Groot HL (2021) European cultural heritage and tourism flows: the magnetic role of superstar World Heritage Sites. Papers Reg Sci 100(1):101–122

Parenti B, De Simone E (2015) Explaining determinants of national UNESCO Tentative Lists: an empirical study. Appl Econ Lett 22:1193–1198

Peacock A, Rizzo I (2008) The Heritage Game. Economics, Politics, and Practice. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Pike A, Rodríguez-Pose A, Tomaney J (2017) Shifting horizons in local and regional development. Reg Stud 51(1):46–57

Revelli F (2013) Tax incentives for cultural heritage conservation. In: Rizzo I, Mignosa A (eds) Handbook of the economics of cultural heritage. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 129–148

Rizzo I (2004) The relationship between regional and national policies in the arts. In: Ginsburgh V (ed) Economics of art and culture. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 203–219

Rizzo I, Throsby D (2006) Cultural heritage: economic analysis and public policy. In: Ginsburgh V, Throsby D (eds) Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture, vol 1. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 983–1016

Rodríguez-Pose A (2013) Do institutions matter for regional development? Reg Stud 47(7):1034–1047

Rodriguez-Pose A, Di Cataldo M (2015) Quality of government and innovative performance in the regions of Europe. J Econ Geogr 15(4):673–706

Rodriguez-Pose A, Garcilazo E (2015) Quality of government and the returns of investment: Examining the impact of cohesion expenditure in European regions. Reg Stud 49:1274–1290

Rodrik D, Subramanian F, Trebbi F (2004) Institutions rule: the primacy of institutions over geography and integration in economic development. J Econ Growth 9:131–165

Serageldin I (1999) Cultural heritage as public good: economic analysis applied to historic cities. In Global public goods: international cooperation in the 21st century, pp 240–263

Tabellini G (2010) Culture and institutions: economic development in the regions of Europe. J Eur Econ Assoc 8(4):677–716

Throsby D (2007) Regional aspects of heritage economics: analytical and policy issues. Australas J Reg Stud 13(1):21–30

Throsby D (2010) The Economics of Cultural Policy. Cambridge University Press

UNDP (2014) Governance for Sustainable Development: Integrating Governance in the Post-2015 Development Framework, United Nations Development Programme

UNESCO (2007) World Heritage: Millenium challenges. World Heritage Centre, Paris

UNESCO (2017) Operational guidelines for the implementation of the World Heritage Convention. https://whc.unesco.org/document/163852

Van Balen K, Vandesande A (eds) (2016) Heritage counts. Antwerp, Garant Publishers

Van der Aa BJM (2005) Preserving the heritage of humanity? obtaining world heritage status and the impacts of listing. Febodruk, Enschede

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Torino within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bertacchini, E., Revelli, F. Kalòs kai agathòs? government quality and cultural heritage in the regions of Europe. Ann Reg Sci 67, 513–539 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-021-01056-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-021-01056-z