Abstract

Objective

To review the literature on retention strategies in follow-up studies and their relevance to critical care and to comment on the Toronto experience with the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) follow-up studies.

Design and setting

Literature review and two cohort studies in a tertiary care hospital in Toronto, Canada.

Patients and participants

ARDS and SARS patients.

Measurements and results

Review articles from the social sciences and medicine are summarized and our own experience with two longitudinal studies is drawn upon to elucidate strategies that can be successfully used to attenuate participant drop-out from longitudinal studies. Three key areas for retention of subjects are identified from the literature: (a) respect for patients: respect for their ideas and their time commitment to the research project; (b) tracking: collect information on many patient contacts at the initiation of the study and outline tracking procedures for subjects lost to follow-up; and (c) study personnel: interpersonal skills must be reinforced, flexible working hours mandated, and support offered. Our 5-year ARDS and 1-year SARS study retention rates were 86% and 91%, respectively, using these methods.

Conclusions

Strategies to reduce patient attrition are time consuming but necessary to preserve internal and external validity. When the follow-up system is working effectively, researchers can acquire the necessary data to advance knowledge in their field and patients are satisfied that they have an important role to play in the research project.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Until recently most intensive care unit (ICU) studies evaluated short-term mortality as the primary outcome. As more patients have survived critical illness, more attention has focused on the evaluation of longer-term mortality, morbidity, and quality of life. As such, a longer follow-up time is necessary to fully characterize these new outcome measures [1]. Regulatory agencies have also recognized the importance of long-term outcomes and are mandating extended follow-up for mortality, functional outcomes, and costing purposes. For these studies to maintain internal and external validity participant attrition rates must be low. Hayes and colleagues [2] noted a wide range (7–100%) of participant retention in their review of the ICU outcomes literature and felt that low follow-up rates were an important limitation in the interpretation of study findings. Consequently the need to understand and adopt strategies to maximize subject retention is essential.

This review highlights successful retention strategies in longitudinal studies from the social science, medical, and nursing literature. Application and discussion of cohort retention methods from the Toronto acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [3–5] and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) [6] longitudinal studies follows the review. The objective of this contribution is to provide a practical set of strategies that may be helpful and relevant for future longitudinal studies in critical care medicine.

Methods and materials

The electronic databases Medline, PsycINFO, and CINAHL were searched (search strategies completed 7 September 2006 and presented in Electronic Supplementary Material 1). Inclusion criteria for review articles were: (a) a primary focus on attrition lowering strategies, (b) multiple longitudinal studies included and summarized, and (c) practical and clinically relevant strategies for patient retention delineated. The bibliographies of eligible manuscripts were scanned for any additional relevant publications. Review articles were also located in Science Citation Index and articles which included them in their bibliographies were examined to determine whether these new publications met our inclusion criteria.

Social scientists have written extensively on strategies to retain subjects in longitudinal studies. Many of these investigators have worked with populations that are extremely difficult to follow, such as substance abusers [7, 8] and adolescents [9, 10]. Several investigators have gone to extraordinary lengths to contact their participants. Some of the methods used may not be acceptable where strict privacy legislation is in place and may not be appropriate for follow-up of ICU survivors. However, one may learn from the perseverance, determination, and ingenuity in these fields of research.

Results

The search strategies for Medline, PsychInfo, and CINAHL yielded 50, 96, and 30 potentially relevant publications, respectively. Abstracts from these searches were evaluated, and when there was doubt about whether an abstract met inclusion criteria for this review, the full text article was read. While many articles discuss the authors' own experiences, only a few summarize strategies used in multiple studies. The eight articles which fulfilled our inclusion criteria are listed in Electronic Supplementary Material 2 [11–18]. All are narrative reviews. No paper was found that quantitatively evaluated the efficacy of the retention strategies. The suggestions offered in the eight articles may be classified into three themes (Table 1).

Respect for patients

The first theme is respect for the patient's ideas and the time they have committed to the research study. All of the reviews emphasized that positive rapport with subjects is essential. Mailing birthday cards, newsletters, and appointment reminders and initiating phone calls to maintain contact between visits are all strategies that can improve subjects' willingness to remain in the study. Davis et al. [16] found that more drop-outs occur in the early months, and therefore it is most efficient to expend time and resources on strategies that establish rapport in the early months of follow-up. Financial incentives must be used with care [16] to avoid the perception of coercion or manipulation. However, patients should be compensated for out-of-pocket expenses such as transportation costs.

Tracking

The second theme addresses the importance of collecting comprehensive contact information at the initial visit. Information on multiple contacts for the patient should be sought. The reason for collecting the information should be reinforced with the patient, who may be encouraged to inform friends and family members that research staff may attempt to contact them. Once family members are aware that the patient supports the research project, they will be less reluctant to provide details of his/her location [12]. One study demonstrated that of all the potential contacts the patient's mother is the most likely person to know where to contact him/her [15]. Two studies recommend an explicit cascade of procedures to be followed [14, 15] in the event of loss of contact starting with the simplest and cheapest. These may include phoning relatives or checking computerized databases and can be performed quickly from the study office. More costly and time-consuming approaches may include traveling to a patient's neighborhood to physically track him/her or purchasing lists from government sources, for example, the drivers' licensing bureau.

Study personnel

The third theme pertains to study personnel. Flexible staffing hours are recommended to ensure that the research interviews are convenient for the patient. Evening and weekend appointments allow subjects to continue with the research when their schedules would otherwise preclude this. Offering home visits, although time consuming and costly, may have a positive impact on retention [12, 14]. Research staff must be adequately trained and supported [13, 14]. Many of the authors used weekly or biweekly staff meetings to discuss progress of follow-up, build team spirit and to combat a sense of isolation often felt by field workers. As well, the personal safety of personnel conducting off-site appointments must be explicitly addressed. One review mentioned training staff in self-defense [12].

Toronto ARDS follow-up study

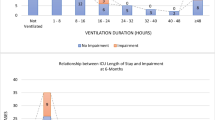

In 1998 we began enrolling patients (109 enrolled) in a 1-year prospective cohort study of survivors of ARDS [3, 4]. Outcome assessments for this study included the 6-min walk test, health-related quality of life, pulmonary function testing, and physical examination. Thus each visit was quite burdensome for patients. The follow-up rates at 1 year and 5 years, respectively, were 86% for surviving participants and 86% for the surviving patients who reconsented for extended follow-up. We used each of the three themes for retention during follow-up from ICU admission to the 5-year clinic appointment. The details of how we applied methods are outlined below and summarized in Table 2.

Respect for patients

The theme of respect for patients is the most important one and must be adhered to throughout the follow-up duration (Table 2) The process of obtaining consent frequently starts with education and provides an opportunity to build rapport with the family. It was not uncommon for this initial step to last 1–2 h or longer depending on the complexity of the patient's illness and the family dynamics. This was a significant time investment, but it was essential for communicating the research team's interest in the care and outcome of the patient.

Once the patient was well enough, he/she was asked for first person consent in order to continue in the study. A copy of the consent form was left with the patient so that study contact numbers were available and informed discussion was possible with family members and/or physicians. A visit to the patient just before hospital discharge by a team member directly involved in follow-up was especially valuable when the follow-up site and the enrolling hospital were not the same. At every meeting both study-related and medical questions were answered, the significance of the study was restated, and our gratitude for their participation was expressed.

Research appointments are very different from patient-initiated clinic visits where a time limit is sometimes tacitly in place. Research subjects were given as much time as they needed. They felt free to offer comments, complaints, and description of ongoing sequelae. They were also given flexibility in scheduling and were sometimes seen outside regular clinic hours. When a subject seemed reluctant to schedule a clinic appointment, a home visit was offered. If a participant indicated that it was not a good time for a visit, perhaps due to other life events, permission was sought to call again in 6 months. Most patients agreed to this, which helped to accommodate subjects' current situation without jeopardizing later participation. While subjects were permitted to opt out of parts of the protocol that they found burdensome, in general all phases were completed. Compliance with questionnaires was lower than that for physical measures.

Home visits, while not historically part of the strategies employed by intensivists, were a critical piece of our retention strategy. Of the 673 completed meetings 214 (32%) occurred in the patient's home; nine patients (11% of our 1- to 5-year cohort) were seen exclusively at their residence. Prior to these visits questionnaires were mailed to participants in order to facilitate their completion. This helped to decrease the length of visits and to increase patient satisfaction.

Tracking

Patients often move or temporarily change their living arrangements. Therefore at the time of third-person consent in the ICU we collected information about the family member who signed the consent as well as the patient's contact information. During the early stages of follow-up phone contact between visits was maintained. We used these calls to ask about health care utilization in order to reduce recall bias. Throughout the follow-up period the coordinator regularly searched the hospital computer system for address changes and for other appointments with which to coordinate our research visit. Annual newsletters were sent out providing interim results (including reprints of any recent publications) and informing patients of international presentations given by the researchers. E-mail contact became an option that some patients liked.

Study personnel

In order to accommodate patients' wishes for visits at nonstandard times, personnel worked flexible hours. This is an ongoing need and is not specific to any of the time periods listed in Table 2. Biweekly meeting were held with the entire study staff to deal with problems that arose and to alleviate feelings of isolation of the field workers. Some ICU survivors lived in neighborhoods which created potential safety concerns for research staff. For this reason, and because our team was exclusively female, visits were always carried out in pairs, at least until research staff became better acquainted with the participants. Single men living alone continued to be seen by two team members.

The principal investigator, a respirologist and intensivist (M.H.), often accompanied the research coordinator on home visits. There was the perception of lack of available care/resources for rural patients even in the context of the Canadian universal healthcare system; consequently, having a physician attend the home visit provided patients with an incentive for ongoing participation.

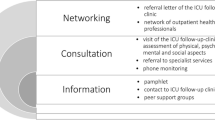

ICU survivors in North America rarely have access to a structured follow-up clinic. These patients are usually discharged home to general practitioners who have little or no experience with the medical issues after critical illness. Thus, consenting for enrollment in a follow-up study provided a link to the medical community that might otherwise have been limited or nonexistent for many patients.

Toronto SARS follow-up study

The Toronto SARS study protocol was modeled on the ARDS follow-up program. We attempted to incorporate and build upon many of the retention strategies that were successful from our ARDS study. This study began in 2003 and enrolled 117 subjects, of which 107 (91%) were seen 1 year from hospital discharge [6]. Patients who refused said that they could not come downtown, had no time for the study, or simply were not interested in further follow-up. Outcomes were the same as for the ARDS study. All enrolled patients were successfully contacted, and few declined follow-up

Respect for patients

The appointments for SARS survivors combined several studies (including several psychiatric in-person questionnaires) into one clinic visit, and thus the total time could be up to 5 h. Therefore we allowed time for a meal and offered complimentary refreshments. Patients were offered the option to break the appointments into two shorter segments, but this option was rarely used. We gave participants a card listing all required assessments for that day so that they had a sense of how much longer they would be in the clinic. This card was very well received. Questionnaires were mailed to all participants in advance of their appointment to facilitate their completion. This helped to decrease the length of visits and to increase patient satisfaction. Funding was not available to compensate for patients' time, but parking expenses were reimbursed. General practitioners are frequently unaware of the recovery process after critical illness. Patients, however, needed referral to specialists and completion of forms from insurance companies, law firms, and workman's compensation boards. Our group felt that although we were conducting an observational study, ethically we could not ignore these requests and the principal investigator (M.H.) addressed these issues. We tried to set the tone of our study as one in which the researchers wanted to learn what the patient had to teach us about the recovery process from a socially stigmatizing illness such as SARS.

Tracking

All tracking strategies used in the ARDS study were again employed in the SARS study but were refined and supplemented as necessary. This population not as sick and thus more mobile and more likely to return to work. Consequently work and cell phone numbers were obtained if patients agreed. We also recorded the phone numbers of a close friend or relative who did not live in the same household as the patient. E-mail was used more often with this patient group as they were more likely to be comfortable with it. Since the planned duration of the study was 1 year, at 6 months we sent out a very detailed newsletter indicating progress on the many substudies that were part of this complicated protocol.

Study personnel

Flexible working hours were encouraged for SARS study employees as were safety measures for home visits. Visits were made in pairs and all personnel carried cell phones.

Discussion

Researchers continue to debate the minimum participant retention rate acceptable to ensure study validity. The social science literature suggests a minimum rate of 70–80% [19]. Despite these guidelines studies with high attrition rates continue to be published and further underscore the difficulty investigators have with retention of study subjects.

It is vital to incorporate retention strategies into follow-up protocols. Significant time is required for planning tracking and retention strategies. Furthermore, an adequate budget is needed to provide enough staff time for these endeavors and to appropriately train interviewers to successfully complete longitudinal studies with minimal subject attrition. Use of e-mail and the internet may facilitate retention. Cotter et al. [15] list a number of web sites that might be useful to track hard to find subjects in the United States, although some of these sites are no longer available.

In conclusion, our work emphasizes the need to build and maintain relationships with patients and to give patients individual attention, time and respect. The strategies discussed here are robust across many study populations, and the concepts are applicable to all ICU studies. The unique contribution of this study is the delineation of the themes of respect for patients and tracking patients over time as they progress from the ICU, to the hospital wards, and reintegrate into the community (Table 2). While many of the ideas presented here are common sense, it is useful to synthesize them so that researchers can identify potential solutions to follow-up problems. Patience, persistence, ingenuity, enthusiasm, and creative teamwork are needed for successful follow-up [19, 20]. In this way intensive care investigators will be able to retain subjects in their follow-up studies, to make their work more generalizable, and to undertake the longitudinal follow-up that will be required after future randomized clinical trials.

References

Vincent JL (2004) Endpoints in sepsis trials: more than just 28-day mortality? Crit Care Med 32:S209–S213

Hayes JA, Black NA, Jenkinson C, Young JD, Rowan KM, Daly K, Ridley S (2000) Outcome measures for adult critical care: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess 4:1–111

Herridge MS, Cheung AM, Tansey CM, Matte-Martyn A, Diaz-Granados N, Al Saidi F, Cooper AB, Guest CB, Mazer CD, Mehta S, Stewart TE, Barr A, Cook D, Slutsky AS (2003) One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 348:683–693

Cheung AM, Tansey CM, Tomlinson G, Diaz-Granados N, Matte A, Barr A, Mehta S, Mazer CD, Guest CB, Stewart TE, Al Saidi F, Cooper AB, Cook D, Slutsky AS, Herridge MS (2006) Two-year outcomes, health care use, and costs of survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 174:538–544

Herridge MS, Tansey C, Matté A, Diaz-Granados N, Mehta S, Guest CB, Mazer CD, Al Saidi F, Cooper AB, Stewart TE, Barr A, Cook D, Slutsky AS, Cheung AM, for the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group (2006) Five-year pulmonary, functional and QOL outcomes in ARDS survivors. Proc Am Thorac Soc 3:A831

Tansey CM, Louie M, Loeb M, Gold WL, Muller MP, deJager J, Cameron JI, Tomlinson GA, Mazzulli T, Walmsley SL, Rachlis AR, Mederski BD, Silverman M, Shainhouse Z, Ephtimios IE, Avendano M, Downey J, Styra R, Webster P, Yamamura D, Gerson M, Stanbrook MB, Marras TK, Phillips EJ, Zamel N, Richardson SE, Slutsky AS, Herridge MS (2007) One-year outcomes and health care utilization in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Arch Intern Med 167:1312–1320

Wutzke S, Conigrave K, Kogler BE, Saunders JB, Hall WD (2000) Longitudinal research: methods for maximizing subject follow-up. Drug Alcohol Rev 19:159–163

BootsMiller BJ, Ribisl KM, Mowbray CT, Davidson WS, Walton MA, Herman SE (1998) Methods of ensuring high follow-up rates: lessons from a longitudinal study of dual diagnosed participants. Subst Use Misuse 33:2665–2685

Boys A, Marsden J, Stillwell G, Hatchings K, Griffiths P, Farrell M (2003) Minimizing respondent attrition in longitudinal research: practical implications from a cohort study of adolescent drinking. J Adolesc 26:363–373

Morrison TC, Wahlgren DR, Hovell MF, Zakarian J, Burkham-Kreitner S, Hofstetter CR, Slymen DJ, Keating K, Russos S, Jones JA (1997) Tracking and follow-up of 16:915 adolescents: minimizing attrition bias. Control Clin Trials 18:383–396

Capaldi D, Patterson GR (1987) An approach to the problem of recruitment and retention rates for longitudinal research. Behav Assess 9:169–177

Cohen EH, Mowbray CT, Bybee D, Yeich S, Ribisl K, Freddolino PP (1993) Tracking and follow-up methods for research on homelessness. Eval Rev 17:331–352

Ribisl Kurt M, Walton Maureen A, Mowbray Carol T, Luke Douglas A, Davidson II William S, BootsMiller Bonnie J (1996) Minimizing participant attrition in panel studies through the use of effective retention and tracking strategies: review and recommendations. Eval Program Plann 19:1–25

Hunt JR, White E (1998) Retaining and tracking cohort study members. Epidemiol Rev 20:57–70

Cotter RB, Burke JD, Loeber R, Navratil JL (2002) Innovative retention methods in longitudinal research: a case study of the developmental trends study. J Child Fam Stud 11:485–498

Davis LL, Broome ME, Cox RP (2002) Maximizing retention in community-based clinical trials. J Nurs Scholarsh 34:47–53

Hill Z (2004) Reducing attrition in panel studies in developing countries. Int J Epidemiol 33:493–498

Marcellus L (2004) Are we missing anything? Pursuing research on attrition. Can J Nurs Res 36:82–98

Desmond DP, Maddux JF, Johnson TH, Confer BA (1995) Obtaining follow-up interviews for treatment evaluation. J Subst Abuse Treat 12:95–102

Cottler LB, Compton WM, Ben Abdallah A, Horne M, Claverie D (1996) Achieving a 96.6 percent follow-up rate in a longitudinal study of drug abusers. Drug Alcohol Depend 41:209–217

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients from both the ARDS and SARS cohorts for their willingness to participate and to continue in the studies until the last visit. We also wish to acknowledge Panos Lambiris, the University Health Network librarian, whose help with the search strategies was invaluable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tansey, C.M., Matté, A.L., Needham, D. et al. Review of retention strategies in longitudinal studies and application to follow-up of ICU survivors. Intensive Care Med 33, 2051–2057 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-007-0817-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-007-0817-6