Abstract

Background

Critical incident reporting systems (CIRS) are considered to be a valid instrument to identify typical errors in various clinical settings as well as in prehospital emergency medicine. Our aim was to review incidents and errors in the care of trauma patients during the period of emergency trauma room treatment before their transfer to the intensive care unit or the operation room.

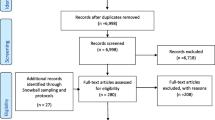

Methods

We screened six open access and German language-based CIRS-platforms on the internet.

Results

We identified 78 critical incidents. They could be divided into four groups: organization related (n = 30), communication related (n = 6), equipment related (n = 28), and medical error (n = 23). Within the category, typical, common, or frequent clusters were identified, such as incomplete trauma team, malfunctioning equipment, or a lack of communication skills. In 12 cases (15.4%), patients were reported to have been harmed, mostly by medical errors. Three reported incidents (3.6%) were considered near-incidents.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that using CIRS is able to reveal individual or rare errors and allows for the identification of systematic errors and deficiencies in the acute care of trauma patients in the trauma room. This may guide quality control and quality improvement measures to be focused on the most common fields of demand.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hohenstein C, Hempel D, Schultheis K, Lotter O, Fleischmann T. Critical incident reporting in emergency medicine: results of the prehospital reports. Emerg Med J. 2014;31(5):415–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2012-201871.

World Alliance for Patient Safety. WHO draft guidelines for adverse event reporting and learning systems. 2005. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/69797/WHO-EIP-SPO-QPS-05.3-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 4 May 2018.

Hansen K, Schultz T, Crock C, Deakin A, Runciman W, Gosbell A. The Emergency Medicine Events Register: an analysis of the first 150 incidents entered into a novel, online incident reporting registry. Emerg Med Australas. 2016;28(5):544–50.

Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, Hebert L, Localio AR, Lawthers AG, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(6):370–6. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199102073240604.

Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, Hebert L, Localio AR, Lawthers AG, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients: results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. 1991. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(2):145–51 (discussion 51–2).

Pucher PH, Aggarwal R, Twaij A, Batrick N, Jenkins M, Darzi A. Identifying and addressing preventable process errors in trauma care. World J Surg. 2013;37(4):752–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-013-1917-9.

Wolff AM. Detecting and reducing adverse events in an Australian rural base hospital emergency department using medical record screening and review. Emerg Med J. 2002;19(1):35–40.

Trentzsch H, Imach S, Kohlmann T, Urban B, Lazarovici L, Pruckner S. Better apprehension of errors in the early clinical treatment of the severely injured. Unfallchirurg. 2015;118(8):675–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00113-015-0029-4.

Major trauma: service delivery. NICE National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG40/chapter/Recommendations#organisation-of-hospital-major-trauma-services. Accessed 4 May 2018.

Frink M, Lechler P, Debus F, Ruchholtz S. Multiple trauma and emergency room management. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114(29–30):497–503. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2017.0497.

Rotondo MCC, Smith R. Resources for optimal care of the injured patient. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 2014.

Quality Indicators for Trauma Outcome and Performance. The trauma audit & research network. 2010. https://www.tarn.ac.uk/content/downloads/27/Quality%20Indicators_26-02-10.pdf. Accessed 6 May 2018.

Parmentier-Decrucq E, Poissy J, Favory R, Nseir S, Onimus T, Guerry MJ, et al. Adverse events during intrahospital transport of critically ill patients: incidence and risk factors. Ann Intensive Care. 2013;3(1):10. https://doi.org/10.1186/2110-5820-3-10.

Jia L, Wang H, Gao Y, Liu H, Yu K. High incidence of adverse events during intra-hospital transport of critically ill patients and new related risk factors: a prospective, multicenter study in China. Crit Care. 2016;20:12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-016-1183-y.

Missbach-Kroll A, Nussbaumer P, Kuenz M, Sommer C, Furrer M. First experience with a critical incident reporting system in surgery. Chirurg. 2005;76(9):868–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00104-005-1034-x(discussion 75).

Zakrison TL, Rosenbloom B, McFarlan A, Jovicic A, Soklaridis S, Allen C, et al. Lost information during the handover of critically injured trauma patients: a mixed-methods study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(12):929–36. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003903.

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Unfallchirurgie. Weißbuch Schwerverletzten-Versorgung. Stuttgart. 2012.

Lawton R, Parker D. Barriers to incident reporting in a healthcare system. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11(1):15–8.

Macrae C. The problem with incident reporting. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(2):71–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004732.

Boyle MJ. Comparison overview of prehospital errors involving road traffic fatalities in Victoria, Australia. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2009;24(3):254–61.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Katherine Noelle Brooks (University of Seattle, 550 17th Ave, 98122 Seattle, WA, USA) for language revision.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Matthias Niemeier, Uwe Hamsen, Emre Yilmaz, Thomas Armin Schildhauer and Christian Waydhas declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Niemeier, M., Hamsen, U., Yilmaz, E. et al. Critical incident reporting systems (CIRS) in trauma patients may identify common quality problems. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 47, 445–452 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-019-01128-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-019-01128-y