Abstract

We present an evaluation of an “in the wild” classroom deployment of Co-located Collaborative Writing (CCW), an application for digital tabletops. CCW was adapted to the classroom setting across 8 SMART tables. Here, we describe the outcomes of the 6 week deployment with students aged 13–14, focussing on how CCW operated as a tool for learning within a classroom environment. We analyse video data and interaction logs to provide a group specific analysis in the classroom context. Using the group as the unit of analysis allows detailed tracking of the group’s development over time as part of scheme of work planned by a teacher for the classroom. Through successful integration of multiple tabletops into the classroom, we show how the design of CCW supports students in learning how to collaboratively plan a piece of persuasive writing, and allows teachers to monitor progress and process of students. The study shows how the nature and quality of collaborative interactions changed over time, with decision points bringing students together to collaborate, and how the role of CCW matured from a scaffolding mechanism for planning, to a tool for implementing planning. The study also showed how the teacher’s relationship with CCW changed, due to the designed visibility of groups’ activities, and how lesson plans became more integrated utilizing the flexibility of the technology. These are key aspects that can enhance the adoption of such technologies by both students and teachers in the classroom.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Digital tabletops have been described as a collaborative tool that can impact educational processes in the classroom [7, 14]. They are considered a medium for social learning [7], and have potential to foster a more collaborative, group-based approach to learning, such as students being exposed to different viewpoints (and possible solutions), developing critical thinking skills and a more nuanced understanding [23].

Recent learning applications have been designed to take advantage of the digital tabletop medium [10, 25, 29, 36]. Much of this research can be characterised as designing applications to exploit the affordances of the digital tabletop to effectively support collaborative learning [7, 21]. For example, DigiTile [24, 25] takes advantage of the visuospatial qualities of the tabletop to support learning about fractions. Students spatially manipulate tiles to fill a canvas to visually represent fractions. Digital Mysteries [10, 12–14] also takes advantage of the visuospatial qualities of the digital tabletop, allowing students to resize, group and connect information to help the groups collaboratively formulate an answer to a question without a distinct “correct” answer. The Collocated Collaborative Writing application (CCW) [8] builds on these design principles, producing a tool for learning extended writing collaboratively. In general, the designs have been found to successfully support collaborative learning interactions, with evaluations showing:

-

1.

Designing for the digital tabletop is more than a remediation of content; it requires specific design in order to fully utilise their affordances [7, 10, 25].

-

2.

Externalisation of thinking can be facilitated by the digital tabletop through visuospatial representations [8, 10].

-

3.

Applications can regulate learning by splitting tasks into stages and through scaffolding [8, 10].

These applications have shown learning improvements for single groups but have not been evaluated in a whole-class setting.

Increasingly, work has been published describing the deployment of multiple tabletops into learning contexts in the wild. Descriptions of classroom deployments of multiple tabletops have shown that there are significant differences and difficulties not found in single tabletop deployments [13] and even in multi-tabletop scenarios that are not integrated into an authentic curriculum setting [11]. This requires:

-

Sessions take place in an ordinary classroom based in a school.

-

Multiple simultaneous groups working on multiple digital tabletops.

-

Supervision by the teacher who usually teaches the lesson to the students.

-

Teacher created content for the sessions based on their teaching goals.

-

Integration of the technology into teachers’ lesson plans and tying the activity to specific learning goals.

The findings have commonly focussed on the design of technological strategies that can support the teacher’s management and orchestration of the class [20]. It is clear from these earlier “in the wild” multi-tabletop deployments [11, 13] that the precursor to an adequate evaluation of the impact of the tabletops, is for teachers to embrace the technology as a tool they can use effectively to support learning by integrating it into lesson plans.

In this paper, we contribute a learning focussed evaluation of a multi-tabletop deployment in a classroom supervised by a teacher during normal lesson time. In so doing, we (1) focus primarily on the nature and quality of one group’s collaboration through the students’ communicative interactions with the technology and each other, (2) track the group’s development over time as part of scheme of work planned by the teacher, and (3) use classroom level data streams to show how this is indicative of the class as a whole. I.e. using the group as the unit of analysis to generalise the collaborative behaviours occurring in the classroom [28].

2 Collocated Collaborative Writing

Collocated Collaborative Writing (CCW) [8] is an application designed to facilitate the learning of extended writing in small groups by exploiting the affordances of digital tabletops. Extended Writing can be characterised as any writing using specialised vocabulary and a formal structure. Planning is an essential skill in producing high level structured writing [15, 17] and good quality plans tend to be well structured (i.e. include well-connected paragraphs), on topic (i.e. not generic or abstract) and lead to higher quality final documents [3]. Writing Frames [18] are a paper-based scaffold to support extended writing. Using specific genres, the method provides partial plan-like structures to be completed by students.

CCW builds on Writing Frames and focuses on persuasive writing (one of the more difficult genres). The genre requires the creation of a persuasive argument across several paragraphs, including supporting evidence and consideration of alternative interpretations. Unlike the paper based Writing Frames, CCW allows the document structure to be changed dynamically. Figure 1 shows the current CCW interface.

The task is split into stages, and students themselves decide (with a decision point) when to attempt to progress. If certain criteria are not met, then the students are given scaffolded instructions to help them towards completing the current stage.

The four stages are: (1) Examine Evidence – students read through the evidence slips. (2) Create (Named) Paragraphs – students create new paragraphs and give appropriate names – a minimum of four paragraphs must be made to progress. (3) Connect Paragraphs – to progress all paragraphs must be connected and (4) Use Evidence: where evidence slips are inserted into paragraphs – to progress, each paragraph must have a minimum of three evidence points, either from slips or created by students.

CCW is designed on principles of collaborative learning [33], incorporating ideas from distributed cognition with focus on the use of space and the manipulation of representations [6, 16, 22, 27, 37]. It also includes teaching methods such as scaffolding [34, 35] to complement and support the scaffolding supplied by teachers. The two main interaction design concepts leveraged to turn writing into a collaborative process are: (1) the use of a visuospatial design allows for representation and communication of ideas, i.e. paragraphs, evidence, and connectors are created as visual representations that can be manipulated by multiple users allowing visual externalisation and communication of ideas. (2) The introduction of decision points throughout the process: between stages, creation of a paragraph, and adding connections. Such decision points help regulate the progress and prompt collaborative discourse, i.e. Proposals [1]. The interface is cumulative; that is, no functionality is lost between stages and additional functionality works on the existing state. Accordingly, the decisions made to reach the current representation can be determined by observing the current state.

The iterative design process of CCW [8] was based on single group studies. Previous integration into the classroom [13] highlighted significant differences between the requirements for a single group and the requirements of a classroom [11, 13].

3 Study Protocol

The study was designed to investigate the relationship between students and the technology through their collaborative behaviours, and that between the teacher and the technology through her feedback and lesson plans. It was conducted over 4 sessions across a half term (6 weeks) in a UK secondary school classroom. The classroom was equipped with 8 smart tables, allowing 8 groups of 3–4 students to participate – 30 students in total. The students were native English speakers of mixed ability, studying English in Year 8 (aged 13–14, key stage 3). Each lesson was planned and facilitated by the class’s usual English teacher, who also produced the session content. Sessions were scheduled to fit in with the existing timetable. The teacher met with the research team to discuss and improve the design before the study and had completed a collaborative writing task using CCW. She designed lesson plans to incorporate the technology into her teaching goals. 2–3 Researchers were present at each session, and sessions were filmed with a classroom camera and a single group camera (Fig. 2). Before each CCW session, the students completed a collaborative exercise, either Digital Mysteries [10] (first 3 sessions) or a classroom debate (final session). The “in the wild” context also had significant practical ramifications, including:

-

The classroom was in use for other lessons during the day, meaning the experimental setup (i.e. all tables and recording equipment) had to be deployed before each session and dismantled after, leaving the classroom in its previous configuration.

-

Schedule restrictions meant that this had to be completed in less than 1 h.

-

The space available in the classroom did not allow a camera per table.

4 Data and Analysis

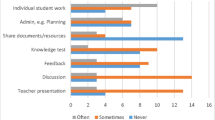

The deployment gathered data from several sources, providing multiple lenses through which to view the deployment using a mixed-methods [5] approach. A classroom camera (Fig. 2a) captured each session, the digital tabletops recorded interaction logs, the teacher recorded lesson plans and reflections for each session, and collaborative document plans and individual written work were generated and assessed by the teacher. A detailed overview of learning interactions can be derived from an analysis of the single group video (Fig. 2b) and audio-recording of each session (n = 4). When synchronised with interaction log data (i.e. creation, manipulation and deletion of visuospatial elements, decisions made and text generated etc.), we were able to provide a detailed view of how learning was scaffolded by CCW.

This paper provides an in-depth, learning-focused analysis of a single group interacting with CCW over four sessions. Using the group as a unit of analysis [1, 28], we tracked development over time as part of scheme of work planned by the teacher. The situated nature of the deployment (i.e. in real classroom, with space and time constraints) restricted data collection opportunities (i.e. video per table) for detailed multiple group analysis. However, other data streams, such as interaction logs, classroom camera and teacher plans and reflections, provided a contextual background.

In order to be able to map a group’s learning interactions to key design features of CCW (externalisation and communication of thinking through visuospatial representations) we utilised an “event-driven” approach to analysis [26]. This allowed us to evaluate, according to distributed cognition, how cognitive processes promoted by CCW were co-ordinated across time, and where events in one session impacted or transformed in later sessions [9].

Bartu [2] uses the concept of Proposals to examine group decision-making processes. Proposals fall within a class of speech acts (that can be non-verbal) which are used to make ‘suggestions’, in order to encourage listener(s) to carry out some future course of action [31]. They are performed according to how the speaker designs an action (e.g. as a question, exclamation, or imperative) [19]. The concept of Proposals maps to the design of CCW through decision points (and visuospatial representations). Based on Bartu’s notion of Proposals we developed an organisational framework to describe the decision-making process incorporating CCW (see Fig. 3). A decision-making episode is initiated through a Proposal. Then a number of different combinations of interactional moves are possible through decision-making ‘speech acts’. These moves, in conjunction with interactions with CCW, allow the speakers to implement a decision scaffolded by CCW. Analysis concentrated on the multimodal interactions at a micro-level, including verbal and non-verbal behaviour that formed the structure of the collaboration, focused on the co-construction of Decisions and use of Proposals to initiate these decision-making processes (i.e. CCW decision points).

Methods from Discourse Analysis (DA) [32] were used to facilitate a systematic and structured way to describe and analyse the organisation of group interactions. This is carried out from the perspective of distribution, co-ordination and impact of cognitive processes over time and the consequences of the design goal of collaborative decision making, i.e. “explore the organisation of social interaction through discourse as coherent in organisation and content and enable people to construct meaning in social contexts” [4]. As such, our analysis examined language and sense-making practices as they were co-constructed across multiple modes of communication including speech, gesture and other contextual phenomena [30]. The DA comprised of two phases. First, decision-making episodes were identified from the video data (independently by two researchers, followed by a consensus). These were marked as stretches of interaction made up of the initiation of a Proposal (as suggested by Barron [1]), subsequent discussion around this Proposal that ended with a decision (see Fig. 2). Secondly, in each episode, the focus of the analysis was on the incremental process of reaching a decision and implementing it (scaffolded by CCW) using Proposals. A double coding of interactional behaviours was performed; two researchers worked first independently, then together to reach agreement about the coding of decision-making ‘speech acts’ within the episode.

5 Results

This section provides a summary of results based on the qualitative and quantitative analysis across 3 data sets: single group video and audio, teacher notes and interaction logs. Observation of decision-making (as a product of interactions with CCW and group members) provide quantitative data concerning use of turn-taking and Proposals. These results were used sequentially – they provided a starting point for looking in more detail at the nature and quality of the decision-making as a collaborative process mediated by CCW. Table 1 displays the number of Proposals identified in each session. Proposals are categorised and quantified (by facilitator, CCW and group), and turn taking is also quantified showing the number of speech acts overall.

When turns are used as a way of evaluating participation, the data suggests that Session 2 produced the lowest rate of participation in the tabletop activity. The highest number of turns, and increased participation was observed in Session 3, slightly decreasing in Sessions 4 and 5. This first phase led the initiation of specific questions concerning the relationship between turns of talk (indicating levels of participation), Proposals (i.e. those occurring away from the table, mediated directly with CCW and from facilitators), and the nature and quality of activity in the interactional space between the initiation of a Proposal and decision-making.

The following sections provide the results for the qualitative analysis of the group interactions with CCW, together with results from the analysis of the teacher’s notes and interaction logs. These data were correlated according to a Convergent Parallel Mixed Methods Design [5]. For each session, an overview of the focus of the lesson is presented, followed by an excerpt providing a detailed micro-view of the nature and quality of interactions with CCW, typical of that particular stage of development of the group in the whole-class deployment. A short commentary of the transcribed episode is then provided which serves as a qualitative account.

5.1 Session 1 – Midsummer Night’s Dream

The students worked on writing a persuasive document answering the question “Which character is the most powerful?” (~20 min) based on a Digital Mystery they had completed in the same session (~45 min). The teacher introduced the session, with topic related notes on the whiteboard, e.g. main characters, groups of characters and brief plot synopsis. The episode comes from the first ‘reading slips’ stage (Table 2).

Commentary:

Despite the high number of turns (Table 1), suggesting a high level of participation, the nature of the interaction in terms of decision making processes (i.e. Proposals) suggests low quality. The episode shows a lack of focus on task demands, evidenced by the intervention by the facilitator and in the quality of the collaboration. Although the students actively watch each other and co-ordinate their efforts, this is not integrated with CCW. Proposals and decisions are made by individuals and are superficial. Those linked to CCW are initiated without prior discussion.

Despite the lack of Finalisation, this episode demonstrates how the nature of collaboration with and around the table is linked to a mutual orientation to the task facilitated by CCW; students’ joint attention to each other’s talk and actions is highly co-ordinated. Students make use of the affordances of the table: demonstrating an understanding that that slips can be selected, read and, if required, trashed.

Classroom Level:

The interaction logs of other tables in the classroom show that no groups completed the task, mostly stopping at the paragraph construction stage. Generally, task-provided evidence was seldom used with groups writing their own outline items. During the session, the teacher moved between the groups and observed that paragraphs were being named abstractly rather than on-topic. She reflected on this in her notes, and decided to incorporate an explanation in the plan for the next session.

5.2 Session 2 – Midsummer Night’s Dream – Part 2

The session, exploring the same question, took around 25 min. The teacher again began with a topic summary, but also included an explanation of good paragraph naming strategies (i.e. on-topic). The teacher reminded the class of this during the paragraph creation phase. Two analysed episodes are presented, connected by the Initiation of Activity (Proposal 1) in Part 1 and the Finalisation linked to that initiation at the end of Part 2 (Tables 3 and 4).

Commentary:

Table 1 suggests a lower rate of participation in terms of turns, however there was a relative increase in Proposals (from facilitators, students and CCW), suggesting a closer task focus from the students and the teacher.

The episodes, as representative of broad patterns of interaction in Session 2, demonstrate an improvement in the quality of collaboration from the first session. Co-ordinated multimodal interaction shows behaviours focussed on specific goals, scaffolded more specifically here by CCW. However, similar Session 1, there is little verbalisation, so actions on the table are not considered by the group before being executed. There is also a continuation of similarly individualised action when M1 directs the connecting of paragraphs to F1. Proposals are generated by students and CCW, co-ordinated to achieve specific interactional goals. CCW and the teacher play a more concrete role in scaffolding decision-making by generating Proposals and mediating those put forward by the group.

Classroom Level:

The logs show that groups changed their paragraph naming strategy after the mid-session reminder and all groups finished the task although some rushed rather than create good answers (particularly with regard to connections and use of evidence). Again, groups did not use the provided evidence, preferring to write their own. Rather than use the generated plans for a text generation exercise, the teacher created a model answer for the students to look at in the next session.

5.3 Session 3 – Greek Mythology

Before the session, the teacher asked students to “assess” her previous session answer. In this session (~25 min), the aim was to create a persuasive document about Greek Mythology. The teacher provided a summary on the board, and the context – writing a Proposal for a museum display. Three episodes are analysed showing how the organisation of the decision-making processes around CCW (based on Proposals) are not isolated events but evolve incrementally, intertwined with previous decisions (Tables 5, 6 and 7).

Commentary:

The session had the highest rate of participation in terms of turns, and also the highest number of Proposals, both from the students and CCW. However, the Proposals provided by the facilitator decreased. The nature and quality of the decision making process increased, as demonstrated in the representative episode.

Students continue to demonstrate joint attention to the task as they watch the text appearing on the table. Central to this change is the occurrence of talk prior to finalisation of decision-making which is implemented using the table. The focus on the content of the paragraphs shows how the Proposals are used in the development of finalisation rather than to initiate it – indicating a change in the distribution of who is leading the process and the role of CCW. These episodes demonstrate a change in terms of the development of decision-making processes from Sessions 1 and 2.

Classroom Level:

Logs show that all groups continued in the “on topic” paragraph naming strategy, but created more topics in less time. All groups created plans that were assessed by the teacher. The teacher reported that writing a “proposal”, rather than a “straight forward” persuasive document, was “too much” for some groups, and decided to go over the “basics” of persuasive writing and choose an easier context.

5.4 Session 4 – Sport vs. Library

In this session the students were working on writing a persuasive argument to decide between funding for a library or new sports facilities at the school (~25 min). They had previously held a classroom debate, including a paper based exercise involving reading and organising evidence and producing a structure they could use to design their document. (Interestingly, the structures mirrored the CCW process without prompting). The teacher provided a short reminder of persuasive texts (Table 8).

Commentary:

Table 1 indicates a high rate of participation in terms of turns (compared to first and second sessions). The number of Proposals remains similar to session 3, however CCW is being used more to implement and scaffold decisions.

As one of a number of similar episodes observed in Session 4, this episode shows how the collaborative nature of decision-making processes with and around CCW has developed across the sessions; culminating in co-ordinated, productive and high quality multimodal interaction. The students actively watch and listen to each other and collaboration contains both individualised and collective Proposals. CCW is used to both initiate Proposals by members of the group (dragging and dropping slips into the paragraph) and support the development of verbal Proposals linked to content which is discussed prior to being added. High quality collaboration is not defined by one decision-making structure but a merging of events built up over the sessions.

Classroom Level:

All groups completed the task, creating plans that were used as the basis for an individual writing homework exercise, assessed by the teacher. The teacher was encouraged by the final documents, reporting that all students showed improvements.

6 Discussion

In this study, we used a single group analysis to obtain a deep understanding of activity at the tabletop throughout a classroom deployment, but also used further classroom data streams to provide a whole class context. We were able to integrate the technology into the analysis of the group’s discourse due to specific design elements of CCW designed to generate Proposals (i.e. decision points), and by adapting Bartu’s model (Fig. 3) to recognise these Proposals alongside those generated through discourse. The multi-tabletop classroom deployment has enabled evaluation of CCW as a learning tool (evidenced through the students’ changing relationship with CCW), as well as provided insights into the teacher’s integral role in integrating technology in the classroom (evidenced through the teacher’s reflection and adaptation of lesson plans).

6.1 Student’s Relationship with CCW

Students had a changing relationship with CCW, which centred on Proposals, and their talk developed across the sessions. The group level analysis allowed us to view the different kinds of collaborative events driving the learning in specific interactions around decision-making processes over time in terms of student, facilitators and CCW. Participants’ use of specific design elements, included to elicit collaborative behaviour such as decision points and visuospatial elements, were also developed.

In the first two sessions, facilitators were the prime source of Proposals and CCW was not central to the students’ talk nor to their activity. CCW Proposals (i.e. through decision points) were used superficially, in an individualised manner and with little follow-on development. In these initial sessions, paragraphs were created with abstract names (until the teacher’s classroom intervention) and task-provided evidence was seldom used. Rather, students made their own points for the paragraphs.

In Session 3, group Proposals were offered and discussed while CCW was used to facilitate the transition of ideas to the plan as a collaborative effort. CCW provided scaffolding via Proposals (decision points etc.) that were attended to by the students. Eventually, CCW could be seen to begin to ‘fade’ [35], with more talk happening off-table before using CCW (to confirm “correctness” before proceeding). Paragraphs were created with on-topic themes, although paragraph connection was still naive. Evidence, was now being used extensively and correctly in persuasive arguments.

In Session 4, Proposals largely came from the group, while CCW mainly implemented shared decision making, i.e. interactional focus was more on the students than the table. Students decided what they wanted to do via talk before implementing their decision on the table. In fact, some CCW design elements (i.e. prompting for group agreement) began to hinder students’ collaboration. The scaffolding provided by CCW “faded”, but the application did not recognise this and still provided the same mechanisms. Task-provided evidence was used in conjunction with the students’ points rather than an all or nothing strategy from previous sessions, i.e. to corroborate persuasive arguments being generated by the students.

As this study has evidenced, the identified changing relationship between students and CCW has clear generalizable consequences on application design. They necessitate that the application design should be flexible enough to allow for such variance in usage. The application should therefore allow for controlling (whether automatically or even manually by the teacher or students) the level of scaffolding, and correspondingly fading, provided. Otherwise, the application’s role may shift from being supportive of the task to being a burden. This variable scaffolding could also be a tool for differentiation across groups of differing abilities across the classroom.

6.2 Integration into the Classroom

A key factor for the impact of the study is how the technology was integrated into the classroom. The teacher is vital in this process, as they control the teaching goals and orchestrate the classroom based on their familiarity with the needs of the students.

Looking at the additional data streams (classroom camera, interaction logs and the teacher’s lesson plans and notes), we can monitor the bigger picture of the classroom over the study. They show how the teacher adapted her plans, during or after the sessions, to get the best out of the technology. She used classroom introductions and interventions to provide background information and suggested strategies for successful persuasive writing (such as on-topic paragraphs). She adapted her assessment approach when it became clear that the students would not complete the task (by supplying a model answer for students to “mark” rather than writing their own). She also appropriated the sessions for use beyond the persuasive writing task, i.e. as a method for bringing out the underlying theme of “power” from the students.

As a class, the data show that the students benefited from the teacher’s adaptive, student-centred teaching approach. The work produced, such as creating and connecting paragraphs and using evidence, increased in quality, but not always linearly. E.g. in Session 3, some groups had lost a focus on persuasive writing, and relied on existing evidence provided by the teacher via CCW. Session 4, saw a move to more persuasive-orientated, student-generated content. In summary, the technology gave the teacher more power to fulfil her teaching goals and benefit the class, rather than replacing some or all of her activities.

The in-the wild nature of the study places a premise on the data collection process. Time and space constraints do not allow for every group to be individually recorded, and so detailed findings from a single group must be combined with higher level data from the classroom level. Examination of interaction logs, classroom camera and teacher notes and reflection allow for general patterns to be identified that indicate that the class as a whole followed a similar pattern to the single group. However, in an ideal world, full data on all groups would yield a more comprehensive analysis.

Despite such limitations, these observations were only possible due to our “in the wild”, classroom based approach. Two important design elements of the application allowed the teacher to make the required observations to adapt her strategy during the sessions (and across the study as a whole):

-

1.

The externalization concepts incorporated into the design and cumulative representation aspects of the design raised the teacher’s awareness of the students’ tendency to use superficial paragraph names and lack of persuasive line of argument, rather than waiting until a post-session outcome assessment.

-

2.

The flexibility of the design enabled the teacher to implement these changes in strategy in the introduction or mid-session classroom announcements, such as assessing group-made plans before individual writing assessment, providing a sample document for students to consider, or focusing on particular task demand.

7 Conclusion and Future Work

We presented an “in the wild” evaluation of a Collocated Collaborative Writing application on multiple digital tabletops. We used video data integrated with interaction logs to gain a detailed moment to moment insight into one group’s learning. We used a classroom camera, interaction logs and teacher plans and reflection to build a context-specific analysis.

We observed that the students’ collaboration progressed from relying on teacher and facilitator Proposals, through using CCW’s scaffolding, to the point where CCW became simply a planning and assisting tool where the scaffolding aspect faded. We found that the visibility of the state, made possible through the cumulative nature of the task, along with the flexibility of dividing the task into stages, enabled the teacher to adapt her lesson plans over the course of the deployment. Moreover, the role of the teacher as classroom orchestrator in conjunction with the technology was vital, requiring a positive relationship with the technology with regard to her teaching goals.

This study has worked towards identifying and understanding more about the nature and quality of learning through CCW in an ‘in the wild’ classroom deployment. It discussed the deployment of the application as part of the ‘machinery’ of everyday classroom life. In doing so, the study’s mixed method approach allowed us to build up an understanding of how the relationship between the students and technology, as well as the teacher and technology, changed over time in the everyday life of the classroom. Some of these behaviours and decisions may prompt for new approaches to teaching and learning (for example, new ways of looking at group collaboration alongside individual work). Yet they also demonstrate how the teacher can still maintain existing practices in terms of classroom orchestration, i.e. technologies can be normalised into the classroom.

This change in relationship between students and technology, which was only observable because of the longitudinal, “in the wild” nature of our study, is not specific to CCW. It demonstrates that any collaborative learning technology targeting the classroom should be flexible enough to take account of such change in relationship, and make such changes clearly visible to the teacher. The design should provide visibility of both task-level details (paragraph names for example), and also higher level usage patterns (such as the overall level of interaction with the technology and communication amongst the group). By allowing such visibility of use, combined with flexibility in implementing teacher’s changes in strategy (whether ‘on the fly’ in-session, or between sessions), it is possible to have the positive relationship with the technology, as shown in this study, which is key to technology adoption in the classroom. This would not have been possible in a lab-based or single-group deployment.

This visible, flexible teacher orientated design approach raises possibilities for further investigation into how such flexibility can be further supported by applications - not only how to support (and design for) different ability levels, but make scaffolding dynamic or adaptive as this relationship changes. This initiated classroom-sensitive questions such as: How much influence should the teacher have over these adaptations? Are they part of the initial lesson plan, or can they be tweaked on the fly? Can orchestration tools be developed that allow teachers to monitor and adapt tasks to enable dynamic differentiation?

References

Barron, B.: When smart groups fail. J. Learn. Sci. 12(3), 307–359 (2003)

Bartu, H.: Decisions and decision making in the Istanbul exploratory practice experience. Lang. Teach. Res. 7(2), 181–200 (2003)

Berninger, V., et al.: Assessment of planning, translating, and revising in junior high writers. J. Sch. Psychol. 34(1), 23–52 (1996)

Coyle, A.: Discourse analysis. In: Breakwell, G.M., Hammond, S., Fife-Schaw, C. (eds.) Research Methods in Psychology. Sage, London (1995)

Creswell, J., Clark, V.P.: Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks (2010)

Dillenbourg, P.: Distributing cognition over brains and machines. In: Vosniadou, S., De Corte, E., Glaser, B., Mandl, H. (eds.) International Perspectives on the Psychological Technology-Based Learning Environments, pp. 165–184. Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah (1996)

Dillenbourg, P., Evans, M.: Interactive tabletops in education. Int. J. Comput. Collab. Learn. 6(4), 491–514 (2011)

Heslop, P., et al.: Learning extended writing: designing for children’s collaboration. In: Proceedings of 12th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children, pp. 36–45 (2013)

Hollan, J., et al.: Distributed cognition: toward a new foundation for human-computer interaction research. ACM Trans. Comput. Interact. 7(2), 174–196 (2000)

Kharrufa, A., et al.: Digital mysteries: designing for learning at the tabletop. In: ACM International Conference Interaction Tabletops Surfaces, pp. 197–206 (2010)

Kharrufa, A., et al.: Extending tabletop application design to the classroom. In: Proceedings 2013 ACM International Conference Interaction Tabletops Surfaces - ITS 2013, pp. 115–124 (2013)

Kharrufa, A., et al.: Learning through reflection at the tabletop: a case study with digital mysteries. In: World Conference Education Multimedia, Hypermedia Telecommunication, pp. 665–674 (2010)

Kharrufa, A., et al.: Tables in the wild: lessons learned from a large-scale multi-tabletop deployment. In: CHI (2013)

Kharrufa, A.S., Olivier, P.: Exploring the requirements of tabletop interfaces for education. Int. J. Learn. Technol. 5(1), 42 (2010)

Kirkpatrick, L.C., Klein, P.D.: Planning text structure as a way to improve students’ writing from sources in the compare–contrast genre. Learn. Instr. 19(4), 309–321 (2009)

Kirsh, D.: The intelligent use of space. Artif. Intell. 73(1), 31–68 (1995)

De La Paz, S., Graham, S.: Explicitly teaching strategies, skills, and knowledge: writing instruction in middle school classrooms. J. Educ. Psychol. 94(4), 687–698 (2002)

Lewis, M., Wray, D.: Writing Frames. Reading and Language Information Centre, University of Reading, Reading (1996)

Markee, N.: Conversation Analysis. Routledge, New York (2000)

Martinez-Maldonado, R. et al.: Orchestrating a multi-tabletop classroom: from activity design to enactment and reflection. In: Proceedings of 2012 ACM International Conference on Interaction Tabletops Surfaces ITS, pp. 119–128 (2012)

Mercier, E.M., Higgins, S.E.: Collaborative learning with multi-touch technology: developing adaptive expertise. Learn. Instr. 25, 13–23 (2013)

Norman, D.A.: Things that Make Us Smart. Perseus Books, Boston (1993)

Piaget, J.: The Language and Thought of the Child. Routledge, New York (2002)

Rick, J., et al.: Beyond one-size-fits-all: how interactive tabletops support collaborative learning. In: Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children, pp. 109–117. ACM (2011)

Rick, J., Rogers, Y.: From DigiQuilt to DigiTile: adapting educational technology to a multi-touch table. In: TABLETOP, pp. 79–86. IEEE, Los Alamitos (2008)

Rogers, Y.: HCI Theory: classical, modern and contemporary. Synth. Lect. Hum.-Centered Inform. 5(2), 1–129 (2012)

Rogers, Y., Ellis, J.: Distributed cognition: an alternative framework for analysing and explaining collaborative working. J. Inf. Technol. 9(2), 119–128 (1994)

Roschelle, J., Teasley, S.: The construction of shared knowledge in collaborative problem solving. In: O’Malley, C. (ed.) Computer Supported Collaborative Learning. NATO ASI Series, vol. 128, pp. 69–97. Springer, Heidelberg (1995)

Schneider, B., et al.: Phylo-Genie: engaging students in collaborative ‘tree-thinking’ through tabletop techniques. In: CHI 2012, pp. 3071–3080 (2012)

Scollon, R., Levine, P.: Multimodal discourse analysis as the confluence of discourse and technology. In: Scollon, R., Levine, P. (eds.) Discourse Technology Multimodal discourse Analysts, pp. 1–6. Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC (2004)

Searle, J.R.: Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1969)

Sinclair, J.M., Coulthard, M.: Towards an Analysis of Discourse: The English Used by Teachers and Pupils. Oxford University Press, London (1975)

Vygotsky, L.S.: Mind in Society. Harvard University Press, Cambridge (1978)

Wood, D., et al.: The role of tutoring in problem solving. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 17(2), 89–100 (1976)

Wood, D., Wood, H.: Vygotsky, tutoring and learning. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 22(1), 5–16 (1996)

Von Zadow, U., et al.: SimMed: combining simulation and interactive tabletops for medical education. In: CHI 2013, pp. 1469–1478 (2013)

Zhang, J., Patel, V.L.: Distributed cognition, representation, and affordance. Pragmat. Cogn. 14(2), 333–341 (2006)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 IFIP International Federation for Information Processing

About this paper

Cite this paper

Heslop, P., Preston, A., Kharrufa, A., Balaam, M., Leat, D., Olivier, P. (2015). Evaluating Digital Tabletop Collaborative Writing in the Classroom. In: Abascal, J., Barbosa, S., Fetter, M., Gross, T., Palanque, P., Winckler, M. (eds) Human-Computer Interaction – INTERACT 2015. INTERACT 2015. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 9297. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-22668-2_41

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-22668-2_41

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-22667-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-22668-2

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)